Justin Duffus

“Can there be culture without melancholia? “

Homi K. Bhabha (A Question of Survival)

“The notion of “bad conscience” developed at the same time as the art of the portrait and accompanied the rise of both individualism and the sense of responsibility. A connection surely exists among guilt, anxiety, and creativity.”

Jean Delumeau (Sin and Fear)

“Everything happens as if there were an original defect in man.”

Henri Gouhier (The Tyranny of the Future)

“…paintings in the age of the internet need to be clever far more than they need to be good.”

John Seed (The Disrupted Realism of the New King Charles Portrait, Hyperallergic 2024)

Increasingly I feel the that the 21st century is marked by the erosion of education. By a evisceration of culture and the social. The loss of curiosity feels acute today. Its always dangerous to so generalize, because there are many curious and smart young people out there, but even within that group, and for all of us, it is hard to escape the effects of what feels like a ‘dumbing down’ of culture. Stupidity has been normalized. The President of the U.S. is obviously cognitively impaired at this point. He is running against Donald Trump, who was accused back in 2017, in Newsweek no less, of suffering from the early stages of dementia. But the culture itself has been badly impacted by a shrinking collective vocabulary, and by an almost wilful amnesia. Many people who might be considered at least relatively sharp are curiously ignorant of history. Both recent history and certainly world history including ancient history. Two near brain dead candidates running for President seems almost normal.

My suspicion is that with so much of daily life mediated by electronic media, even in places with far fewer computers, and this coupled to the loss of books, and the disintegration of public education, there exists a new kind of background to our lives. A background that has as its most salient quality, an utter opaqueness. And I think this is true even for those, like myself, who think we are critiquing something that, therefor, we view from a distance.

But in my more lucid moments I know this is not completely true.

Daniel Ochoa

The manner of the reproduction of our culture, or rather the narrative that is in place to tell the story of our culture is of necessity reproduced over and over. Hence the equation of repetition. Freud’s most significant insight, in a sense. But this is a period, an epoch, of transition. Gramsci’s much quoted (and often misquoted and mis-translated) description of such epochs, ones that produce irrationalities:

“The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.”

Antonio Gramsci (Prison Notebooks)

Today the ruling class exists only through coercion.

“For Saint Paul, sin and death entered the world at the beginning of history, and ever since then the world has -been in league with the mysteries of evil (Rom.5:12). From-the moment in which Adam relinquished the domain God had entrusted to him, Satan became the “prince” and even the “god” of the times~(John 12:31,14:30). Man is therefore surrounded and even penetrated by a deceitful world, which is in opposition to the Spirit of God and whose wisdom is naught but folly (I Cor. 1:20). “

Jean Delumeau (Ibid)

By the end of Antiquity there existed, in the Christian world, as a prevailing belief that the vanity of the world was central to our experience of it — and this drove the ascetics, the so called Desert Fathers, into a kind of exile where they lived and meditated on the problems of sin and redemption. It was a kind of protest against a Church they believed had grown lax.

“Later,throughout the Middle Ages, this same doctrine inspired the spiritual life of convents, where the lives of the desert fathers were read with great fervor. A resurgence of a dualist myth has been discerned in the asceticism of monastic life, a myth that survived principally in Bogomilism and Catharism. According to this myth it was Original Sin that was responsible for having precipitated the soul into matter.”

Jean Delumeau (Ibid)

Its curious that I had bought Delumeau’s book years ago. Maybe ten years ago, in fact, but never read it. I cannot even remember where or why I bought it. Then as I continue to unpack after our recent move I came across it again. And I have had this experience many times. The book returned to me as if by magic, when I needed it. And I say *needed* it because I feel this is a perspective that is perhaps overlooked a good deal. The origin of western guilt, and atonement, and maybe also of sin.

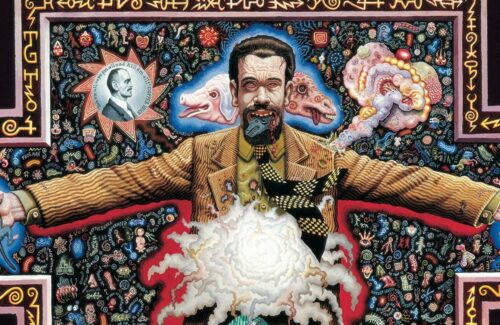

Joe Coleman

Also note that Delumeau is a staunch conservative of the Academy. Supported Macron even. But sometimes such is the character of classically minded historians. It does not disqualify them, but it does warrant mention.

The evolution of interiority is something I have addressed in many of these posts. Its a recurring theme of this blog. And I continue to insist on the lasting importance of psychoanalysis, and of Marxism, and of an ongoing historical focus. Ongoing deep history.

“ I suspect psychoanalysis survives in part because it offers something unique—and perhaps subversive—with implications beyond the consulting room. If nothing else, the slander and repression repeatedly directed at psychoanalysis accords with the treatment of subversive forces. As Lear (1998) observes, “A battle may be fought over Freud, but the war is over our culture’s image of the human soul” —specifically over questions of liberty, irrationality, and unconscious motivation. Perhaps psychoanalysis survives because it obstinately carries a torch of wild freedom and reverence for the unknowable in a world of rational epistemology and increasingly rigid sociopolitical control. Psychoanalysis does not scream its sociopolitical agenda, waving signs and shouting slogans, but may be a fundamentally political project nonetheless, and one of a subversive nature.”

Amber M. Trotter (Psychoanalysis As a Subversive Phenomenon)

The middle ages saw a recalibration of inwardness. And much of it came out of the Egyptian deserts and the monks and scribes living as hermits in caves. Now, much later, around the end of the 18th century, there emerged this idea of nationalism. And this idea has proved extraordinarily durable. For Marxists this is, as Benedict Anderson put it, an anomaly.

So perhaps I want to try to track interiority and what is understood today as nationalism or patriotism, and how both intersect with culture. It was mentioned on our recent podcast (https://aestheticresistance.substack.com/p/podcast-112 ).

“…the special relationship between contempt for the world and the concept of mortality deserves a second glance. { } two phenomena help to explain the role assigned to death in this period: the long process of religious “culpabilisation” and acculturation that, originating in monasteries, spread out in concentric circles so as to reach larger and larger segments of the population, and (2) a profound pessimism stemming from an accumulation of different types of stress, which dominated European

thought (especially that of the elite) from the time.of the Black Death to the end of the Wars of Religion. { } Such docile acceptance of this universal and immutable law has long been associated with belief in the survival of a “double.” { } Like the members of many other civilizations our ancestors found it difficult to accept the abrupt disappearance of those with wHom they had shared their lives. Thence they believed in ghosts, which testify to the continuing presence of the dead— at least for a certain time, in other words, the dead took a long time to actually pass away.”

Jean Delumeau (Ibid)

Anne Harris

“The United States has always, arguably, been a nation of believers, deeply invested in our beliefs. The hunger of early Protestant Pilgrim’s for the freedom to believe has had a defining influence on American politics. Further, the persistence of advanced capitalism in light of its staggering and widespread damage has become difficult to explain through material analysis alone. While certainly current economic circumstances are perpetuated by structural coercion, the ideology of late-stage capitalism has become so deeply ingrained that it is reflexive. ”

Amber M. Trotter (Ibid)

Trotter refers to ideological manipulation as a sinister hypnosis. The subversive ethics she advocates is precisely so difficult because it defies prediction. And prediction is a cornerstone of the scientism of ruling class ideology.

“Contemporary society thwarts agentic, rebellious subjectivity. It frustrates deconstructive, antinomian, and complexity dimensions of analytic freedom. A breakdown in thinking marks contemporary politics across the political aisle. Neoliberal capitalism tightly regulates not only work, but also leisure or free time, foreclosing critical analysis and reflective spaces through its long productive hours and hypnotic entertainment. { } Digital capitalism also demands a sort of personality commodification and marketing antithetical to analytic character development. In a world where material resources are largely controlled by a powerful elite, we are forced to mine our selves for a living—we have become the product in our modern economy. At ever younger ages, we mold our subjectivity through the algorithm of cultural capital and profitability.”

Amber M. Trotter (Ibid)

The evolution of interiority took a marked leap with the advent of the internet. On one level the internet, and particularly social media use, amplified trends already in place, and behavior already in place.

Ming Smith, photography.

“Concerning the broader question of whether social media is causally related to the rise in rates of adolescent mood disorders, self-harm, and suicide since 2010 in the USA and UK, it has been pointed out that the rise paralleled the years “when American teens were obtaining smart phones and becoming daily users of social media platforms such as Instagram” . The same is true of the unique clinical presentation of FTLBs (Functional tic-like behaviors) which first emerged into clinical awareness in 2019 in Germany, as well as with the increasing recognition of the DID-plurality (Dissociative Identity Disorder) community and emergent discourse. More broadly, there has been a recognition of vast online ‘neurodivergence’ ecosystem in which classical mental illness symptoms and diagnoses are viewed less as mental health concerns that require professional attention, but rather as consumer identities or character traits that make individuals sharper and more interesting than others around them.”

John D. Haltigan, Tamara M. Pringsheim, Gayathiri Rajkumar (Social media as an incubator of personality and behavioral psychopathology: Symptom and disorder authenticity or psychosomatic social contagion? Comprehensive Psychiatry, vol 121)

The conditioning in young people, in the West mostly, to shop for everything, including themselves, is not new. Even I was writing about this a dozen years ago. Shop for an identity, and then *own* that identity. The rise of victims rights cuts across this evolution of self diagnosing psychiatric disorders. And I have linked to the great article by Lynne Henderson before, but I will do so again. https://scholars.law.unlv.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1894&context=facpub

The Covid lockdowns accelerated existing trends further…

Y.Z. Kami

“Between 2011 and 2017–18, rates of adolescent depression in the U.S. increased at least 60%, with larger increases among girls. Happiness and life satisfaction declined after 2012. Emergency department admissions for self-harm behaviors tripled among 10- to 14-year-old girls between 2009 and 2015. Emergency department admissions for suicide attempts or ideation doubled or increased substantially, as did self-poisonings.”

Jean Twenge (Current Opinion in Psychiatry, Vol.32, 2020)

The entire social scaffolding that supports these responses to adolescent anxiety and depression always somehow feels like a machine that manufactures the anxiety in the first place. This is a tricky area, though, because one would be hard pressed to deny that organized mental health responses are not needed. But there are strings, even with the best, even if invisible. Some strings are not invisible, needless to say. In LA there are guarded and fenced *homes* for the unhoused. Shelters. Individual very tiny sheds. And there is 24 hour a day surveillance and there is a curfew. And there are even guard towers and 24/7 spot lights. The omnipresent and harsh illumination serves as its own allegory here.

The minds that created this ‘village’ are the product of the same forces that created those with addictions or compulsions, or one or another disorder that prevents them from working. And there are some who just had bad luck. Those who are the product of capitalist class based economics.

But treating mental health issues is profoundly preferable to incarceration. The problem is, those crippled with addictions, say, are psychically identical to those who create these dystopian solutions.

“The gap between ‘already’ incapable bourgeois rule and ‘not yet’ capable workers’ rule likewise constitutes a fertile ground for the rise of another serious disorder: not of socialist orientation, but of bourgeois politics in the form of the far right. The surge of the latter typically happens when traditional bourgeois rule starts losing legitimacy (consent, hegemony) against a backdrop of socio-economic crisis while the anti-capitalist left is not yet strong enough to take the lead among the people (the nation).”

Gilbert Archar (Morbid Symptoms; Journal for Studies on Power)

I hesitate to ever quote Archar, but for the purposes here, the above is useful.

Going back to the transition from antiquity to feudalism, and then the later changes in Europe after about 1500. With the advantage of hindsight it is interesting to look at the beliefs of feudal classes, and the differences between France and England, between the Germanic fiefdoms and the far, far North. The psychological inheritances are complex, but also not so often examined.

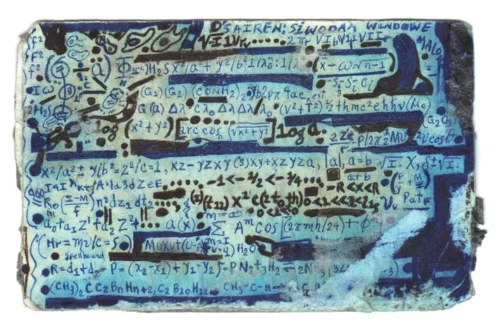

Melvin Way

“Man is formed of dust, mud, ashes, and, what is even viler, of foul sperm . . . Who can ignore the fact that conjugal union never occurs without the itching of the flesh, the fermentation of desire and the stench of lust? Hence any progeny is spoiled, tainted and vitiated by the very act of its conception, the seed communicating to the soul that inhabits it the stain of sin, the stigma of fault, the filth of iniquity— in the same way that a liquid will corrupt if it is poured into a dirty vessel. . .”

De Contemptu of Innocent III, (see C. Martineau-Genieys, Le Theme de la mort dans la poesie franqaise de 1450 a 1550)

I am jumping around a bit here. (I am often accused of digressing). But there are connections I feel I am searching for. The state of psychological malaise today, the self diagnosing (the online communities of self diagnosed), the war mongering, the loss of curiosity, the loss of skepticism, the growing assisted suicide phenomenon; all of it has precedents. All of it is specific and not random. The rise in self harm and suicide is mirrored in this new seeming desire FOR war. Its yet another form of suicide.

“Widespread disintegration of intimate, private relationships further undermines subversive ethical engagement in the present moment. The logic of global capitalism, especially in its latest digital form, is one of exchangeability, displacement, and atomization. It weakens social bonds and collaborative projects of all kinds—including political resistance.”

Amber M. Trotter (Ibid)

The peasant of the Crusader state in the levant was closer emotionally to his own mortality than are we to ours. Eric Hobsbawm notes that even by the 1780s, most of the world was unmapped (there is a whole essay asking to be written about the role of maps in our psyches). Also, three out of four humans were Asian, and only one out of five were European. The guess is one in ten were African. Less for north American and Oceana. And the average European (these are somewhat guesses, but there are records of conscripts to the military) were around 5′ 2″.

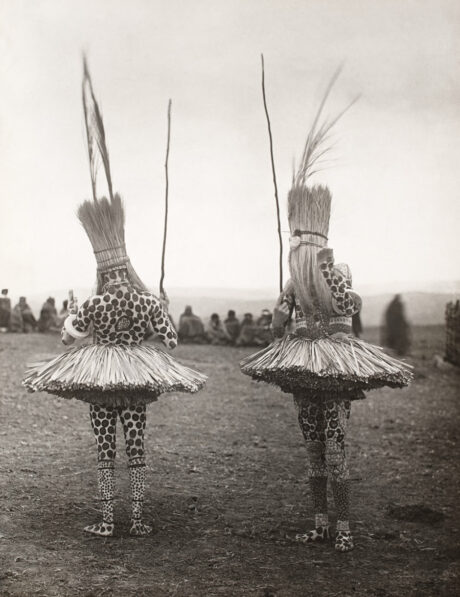

A.M. Duggin, photography (1930, South Africa)

Histories were European. The European culture were given to note taking and measuring their lives. At least they were prone to measuring their property. Chinese society did, too, but to a lesser degree. Much of the culture of the world, let alone Europe, was Roman in sensibility.

“The world of 1789 was therefore, for most of its inhabitants, incalculably vast. Most of them, unless snatched away by some awful hazard, such as military recruitment, lived and died in the county, and often in the parish, of their birth: as late as 1861 more than nine out often in seventy of the ninety French departments lived in the department of their birth. The rest of the globe was a matter of government agents and rumour. There were no newspapers, except for a tiny handful of the middle and upper classes—5,000 was the usual circulation of a French journal even in 1814—and few could read in any case.”

Eric Hobsbawm (Age of Revolt)

Most travel (and the mails and definitely for cargo) was by water. The sense of ‘time’ was simply different. It was 36 hours by horse drawn coach from Paris to Strasbourg. From feudalism to what Hobsbawm calls the age of revolt was viewed by the people of the time, if I can be egregiously generalizing, as one of progress — the Industrial Revolution was underway already. The Enlightenment is usually marked as 1685 to 1815 — the ‘long 18th century’. Inculcated in the educated classes was the idea of progress.

Life was rural. Overwhelmingly rural. Over 90% of Europe was rural. There were two huge cities, Paris and London.

“The Industrial Revolution not only transformed both city and country; it was based on a highly developed agrarian capitalism, with a very early disappearance of the traditional peasantry. ”

Raymond Williams (The Country and the City)

Radu Belcin

The culture was tied as much to provincial towns as to the few big cities. I go into all this here because it feels like ‘the’ pivotal moment in modern history. The provincial town of this era was tied to the peasantry. This was a world of clerks and traders in agriculture and livestock. Bookeepers. Notaries. And much of the bookeeping, when not tied to the peasantry and the peasant economy was involved in noble estates. But the backdrop for western consciousness at this point was the countryside. And this implied and included an idea of ‘nature’.

“ For it is a critical fact that in and through these transforming experiences English attitudes to the country, and to ideas of rural life, persisted with extraordinary power, so that even after the society was predominantly urban its literature, for a generation, was still predominantly rural; and even in the twentieth century, in an urban and industrial land, forms of the older ideas and experiences still remarkably persist. ”

Raymond Williams (Ibid)

The intellectual legacy of the middle ages lived on, too. The economic issues and the thinking that developed around economics was tied to the ‘agrarian problem’.

“The characteristic economy of the slave-plantation zone, whose centre lay in the Caribbean islands, along the northern coasts of South America (especially in Northern Brazil) and the southern ones of the USA, was the production .of a few vitally important export crops, sugar, to a lesser extent tobacco and coffee, dye-stuffs and, from the Industrial Revolution onwards, above all cotton. It therefore formed an integral part of the European economy and, through the slave-trade, of the African. Fundamentally the history of this zone in our period can be written in terms of the decline of sugar and the rise of cotton.”

Eric Hobsbawm (Ibid)

An interesting and relevant detail here is the vastness of some of the estates in underdeveloped areas to the east — Catherine the Great gave the Radzwills of Poland over 40 thousand serfs as a present.

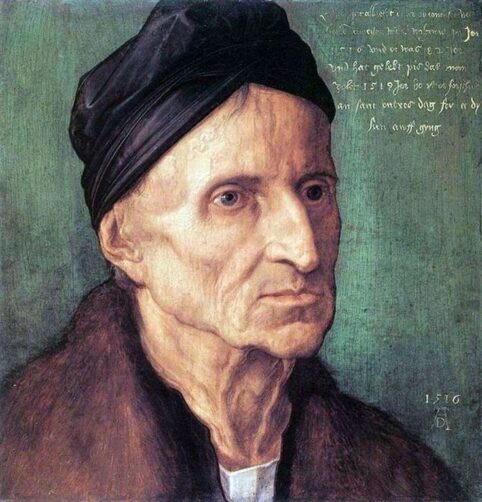

Albrecht Dürer (Portrait of Michael Wolgemut, 1516)

“The opening of the Black Sea route and the increasing urbanization of Western Europe, and notably of England, had only just begun to stimulate the cornexports of the Russian black earth belt, which were to remain the staple of Russian foreign trade until the industrialization of the USSR. The eastern servile area may therefore also be regarded as a food and rawmaterial producing ‘dependent economy’ of Western Europe, analogous to the overseas colonies. The servile areas of Italy and Spain had similar economic characteristics, though the legal technicalities of the peasants’ status were somewhat different. Broadly, they were areas of large noble estates. It is not impossible that in Sicily and Andalusia several of these were the lineal descendants of Roman latifundia, whose slaves and coloni had turned into the characteristic landless day-labourers of these regions. Cattle-ranching, corn-production (Sicily is an ancient export-granary) and the extortion of whatever was to be extorted from the miserable peasantry, provided the income of the dukes and barons who owned them.”

Eric Hobsbawm (Ibid)

There remains even today a clear class lineage among the European aristocracy. One that should not be forgotten. Ursula van der Leyen traces her family back to slave traders, which is from where they obtained their wealth. Property was kept in the hands of the gentry, the noble families, or the Church (and in places it was hard to distinguish between them). But the slave trade cannot be minimised in importance. The sluggish agricultural sector of the European economy was offset by the new overseas colonies and the trade routes across the Atlantic. From the 18th century the story is the slave trade.

“For indeed the conviction of the progress of human knowledge, rationality, wealth, civilization and control over nature with which the eighteenth century was deeply imbued, the ‘Enlightenment’, drew its strength primarily from the evident progress of production, trade, and the economic and scientific rationality believed to be associated inevitably with both.”

Eric Hobsbawm (Ibid)

Now, the point to this fragmented and brief history is suggest the origins of many contemporary conceits about the productive duties of citizens, and about nature. The ideology of the Enlightenment was viewed as the distancing of the individual from the superstitions of the Church, and backwardness of the middle ages. There was a new enthusiasm for skill and innovation. And a belief in individualism.

Andrea Castro

My interest here is the motivations instilled by ideas of progress. Progress is relevant not to the nobles or aristocracy, but to the workers and clerks and merchants. The provincials. Provincials from the thousand provincial cities, or towns really, or large villages. Under twenty thousand inhabitants. This was the seat of the dream of progress.

“…these also were the towns out of which the ardent and ambitious young men came to make revolutions or their first million; or both. Robespierre came out of Arras, Gracchus Babeuf out of SaintQuentin, Napoleon out of Ajaccio.”

Eric Hobsbawm (Ibid)

This is profoundly important in understanding the psyches of the western bourgeoisie. One of the misreadings of what is called Critical Theory is that thinkers like Habermas (and Axel Honneth) remain apologists for Imperialism (and advocates for the idea of progress) and because of this much of the anti-Imperialist discourse lumps Adorno and Horkheimer in with Habermas. I mention this because I think the idea of progress runs very deep in the western mind. But progress colours our language and even our spiritual beliefs. The entire new age movement from the 60s on is infused with a crypto-progressive ideology.

In the 18th century, ambitious provincials came to the cities. A good deal of European literary output is devoted to this. The very form of the novel is predicated, in a sense, on the ‘journey of the provincial’. The journey of progress, of betterment and an arrival at the depot of ‘success’. Not too many thinkers even bothered to ponder what success might look like. Adorno and Horkheimer’s critique of the Enlightenment was not (and Edward Said even said this) *universal*. This is really a dreadful misreading of the Frankfurt School’ oeuvre. The philosophical autopsy performed by Adorno and Horkheimer was actually far more historical than any of their critics. And its alleged ‘universalism’ was more a structural logic than it was intellectual neglect.

“Iconic American heroes are frequently self-made. The narrative of “rags to riches” looms large in our collective psyche—and not without reason. A measure of truth adhere in the idea that, at least historically, for certain subpopulations, sufficient hard work led to considerable prosperity (Bellah et al., 2008). Women, slaves, and native peoples were excluded from this narrative, but in contrast to aristocratic Europe, the young United States offered white men an expanded opportunity to advance themselves through hard work, regardless of birth. As with happiness and successfulness, productivity is cast as a characterological virtue, vital to self-esteem, and estimation by others. Pride in workaholism is a widespread phenomenon: Americans brag about grueling hours, insufferable conditions, and other sacrifices made for work (Kantor & Streitfeld, 2015; Tolentino, 2017). ”

Amber M. Trotter (Ibid)

Frank Gohlke, photography (Dodge City, Kansas, 1973.)

If 18th and early 19th century narrative writers were still writing within an imaginary that was more 17th century, one of rural landscapes and these small provincial towns and cities, this morphed into something like non landscapes by the 21st century. That 17th century landscape, that depiction of *nature* was still there, but invisible. Or opaque. A present absence, as it were. The great fiction writers of the 20th century, when examined in this way, were to a degree (often large degree) interrogating the assumptions of success, but also of these landscapes. They were investigating the migration from outside to inside. Kafka distilled these interrogations. By the mid 20th century however, the ascension of film had subsumed literature. And film is paradoxically a more isolating medium than literature.

“The roots of the antisocial attitude run deep. They find their origin in all the structural features of our society that are ambivalent or antagonistic toward our greater social impulses: the creep of market logic into even the most private parts of our lives, the drive to privatize everything that was once public, and, of course, the tendency for work-life to devour the rest of life. Since at least the middle of the last century we’ve witnessed the decline of participation in team sports, voluntary associations, labor unions, social clubs, political organizations, and charitable causes. The march toward social isolation has been a long one.Yet with the pandemic, the implosion of social life has become particularly acute. Today, Americans are more alone, and more lonely, than ever before. ”

Dustin Guastella (Anti-Social Socialism Club, Damage Magazine, March 2023)

The French Revolution was a watershed in several respects, but for the purposes here, it is relevant because the Jacobins were pre-Industrial Revolution. The shape of collectivity was forever changed.

“War was declared in April 1792. Defeat, which the people (plausibly enough) ascribed to royal sabotage and treason, brought radicalization. In August-September the monarchy was overthrown, the Republic one and indivisible established, a new age in human history proclaimed with the institution of the Year I of the revolutionary calendar, by the armed action of the Sansculotte masses of Paris. The iron and heroic age of the French Revolution began among the massacres of the political prisoners, the elections to the National Convention—probably the most remarkable assembly in the history of parliamentarism—and the call for total resistance to the invaders. The king was imprisoned, the foreign invasion halted by an undramatic artillery duel at Valmy. Revolutionary wars impose their own logic. The dominant party in the new Convention were the Girondins, bellicose abroad and moderate at home, a body of parliamentary orators of charm and brilliance representing big business, the provincial bourgeoisie and much intellectual distinction. Their policy was utterly impossible. For only states waging limited campaigns with established regular forces could hope to keep war and domestic affairs in watertight compartments, as the ladies and gentlemen in Jane Austen’s novels were just then doing in Britain. “

Eric Hobsbawm (Ibid)

The west today traffics in a sort of short-hand or abridged and coded collective memory. Hollywood has, sadly, a lot to do with this. And so repetitive and jingoistic is film and TV today that audiences anticipate what they know is coming. Stories are not really stories, they are like the platforms of social media. Interior ‘like’ clicks. I suspect this occurs even in personal relationships. Narratives are like advertising spots. In fact there is largely no difference anymore. And in such mini-narratives there is no room for complexity. History becomes code.

Vera Molnár

And since this is all reproduced through class dynamics, or through the erasing of class dynamics, more accurately, the French Revolution (for example) is that of a Sophie Coppala film (Marie Antoinette, 2006). The much noted lonliness of contemporary life is inevitable somehow given the educational deficit in play. Intimacy has *like* or *block* buttons.

“For a mass of people to be led to think coherently […], the question of language in general [linguaggio] and languages in the technical sense [lingua] must be put in the forefront of our enquiry.”

Antonio Gramsci (Prison Notebooks)

“..it is characteristic that Gramsci should frequently identify social problems in terms of language symptoms.”

Marcia Landis (Culture and Politics in the Work of Antonio Gramsci, Boundary 2, 14/3)

“It was not just Italy and Germany, but in one way or another all the countries intervening in the First World War,which shared this sickness. Fascism was, then, a parenthesis which had coincided with a reduction in the consciousness of liberty.”

Ernesto Laclau (Politics and Ideology in Marxist Theory)

The sickness today is one that cannot be reduced to its symptoms. The genocide in Gaza, which is not over as I write this, will be remembered as an enduring symbol of this sickness. It is a composite of everything noted above. It is also, through the readings of many who comment on it, a lens for the sickness of white supremacy. Of white driven Imperialism. The Gaza atrocities have already come to be treated with snark and irony. With white privilege. Hamas is an inconvenience to the white west, whatever the individuals sympathy. And as with the rise of fascism after WW1, one cannot escape the sickness.

To donate to this blog and to the Aesthetic Resistance podcasts, use the paypal button the top of the page. All donations are much appreciated. We do not monetize any of our work.

Speak Your Mind