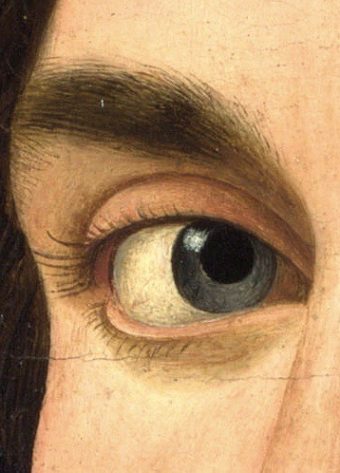

Hieronymus Bosch (Christ’s Descent into Hell, detail. 1540. Judas)

“So many things happening, so many stories one inside the other, with every link hiding yet more stories … And I’ve hardly hatched from my egg,” thought an exultant Garuḍa, heading north. At last a place with no living creatures. He would stop and think things over there. “No one has taught me anything. Everything has been shown to me. It will take me all my life to begin to understand what I’ve been through. To understand, for example, what it means to say that I am made of syllables …”

Roberto Calasso (Ka: Stories of the Mind and Gods of India )

“Much seems to be fixed…Perhaps it was once disputed. But perhaps, for unthinkable ages, it has belonged to the scaffolding of our thoughts.”

Ludwig Wittgenstein (On Certainty)

“We start to believe the world is predictable, because in certain circumscribed circumstances it seems to be so. But this is a delusion.”

Iain McGilchrist (The Divided Brain and the Search for Meaning)

“Now it [the eye of the stranger] was fixed upon Yillah with a sinister glance, and now upon me, but with a different expression. However great the crowd, however tumultuous, that fathomless eye gazed on; till at last it seemed no eye, but ever a spirit, forever prying into my soul.”

Herman Melville (Mardi)

“Now it is not only conjectural but probable that this voice which I hear is that of a man and not a song on a phonograph; it is infinitely probable that the passerby whom I see is a man and not a perfected robot.”

Jean-Paul Sartre (Being and Nothingness)

In my last blog post a reader commented on neuroscientist Iain McGilcrhist’s work on the brain. I rather impetuously dismissed the work, after watching a few minutes of the video. I was wrong, and I wrote my reader to apologize for so badly misreading McGilchrist. Now, I have spent the last couple weeks pouring over McGilchrist’s books and lectures and it serves as a very useful starting point for a further discussion about consciousness, the world, and our culture. And about science.

And while I was wrong, I think I was not totally wrong. But I think I was wrong in the wrong way, certainly. If that makes sense. But McGilchrist is not your average scientist and his status as a sort of unconventional theorist about the brain is hugely valuable. That said, there are still troubling and perhaps just confusing aspects to some of what he says. And this also touches on my last post about Benjamin, and before that in the post that featured a good deal of Ernst Bloch’s ideas. These posts run together a bit in my head, and I think they will both be referenced here.

The second point here is that I write this from a hospital bed in Trondheim. My heart stopped during a chess tournament. I was fortunate to be across the street from a hospital and to have a chess playing doctor in the tourney. But I was without heartbeat for over two minutes. I only can remember feeling a bit dizzy for a half second, and then waking in the ambulance, or just outside the ambulance where they applied the Defibrillator. This will no doubt colour the writing of this post (my casual boyish insouciance is intentional.)

Antonello da Messina (Portrait of a Man) detail. 1475.

McGilchrist shares certain similarities with V.S. Ramachandran, the Indian neuroscientist and the author of a few books for the lay reader on the brain. Not unlike Oliver Sachs, actually. And what is interesting is that these scientists are the other route to discussions of consciousness.

Now the first thing to note is that both McGilchrist and Ramachandran tend to employ a lot of metaphor, and both make note of this. In fact both find it to be a very specific inherent aspect of brain functioning. But neither man is interested in the content of these metaphors. Its funny if you watch one of Ramachandran’s TED talks on Youtube, where he half jokingly dismisses Freudian theory, only to exactly reproduce a Freudian explanation for the Capgras delusion condition. Either that or he didn’t really understand the Freudian theory. Capgras Delusion is when someone believes others they are close to, such as mothers or siblings are actually imposters. Whatever neural damage or cross wiring causes this, still begs the question of what ‘recognition’ is (which is what philosophers ask) and how language itself intersects with such conditions. How ‘we’ learn what recognition means, how we learn the meaning of all words, all language. If the Capgras sufferer thinks his wife is an imposter, then from whence came the idea of ‘imposter’? And what does imposter replace? Presumably the ‘real’ person. But the idea of real has to be learned, although that begs other questions. If the child’s first experience of recognition is the Mother, and second the Father, then one might assume this primary relationship forms the template for ideas of imposture. But more on this below.

Even these two rather remarkable scientists assume a stable world view in which cause and effect are studied free of matters such as philosophy or politics. Now before anyone objects, yes McGilchrist does go out of his way to stress the importance of philosophy, and of the humanities in general. But such considerations remain rather peripheral to the experiments. Though in both cases these men are hardly blind to the conundrum.

Analia Saban

“One could call the mind the brain’s experience of itself. Such a formulation is immediately problematic, since the brain is involved in constituting the world in which, alone, there can be such a thing as experience – it helps to ground experience, for which mind is already needed. But let’s accept such a phrase at face value. Brain then necessarily gives structure to mind.”

Iain McGilchrist (The Master and his Emissary)

McGilchrist points out that all attempts at explanation depend on parallels with which one can compare thing meant to be explained. But there is nothing parallel to consciousness.

He then adds: “Mind has the characteristics of a process more than of a thing; a becoming, a way of being, more than an entity.”

(Ibid)

This is very important, I think. For to return to Benjamin (and Freud, and Lacan, from previous posts) this idea of process has been a convenient (and perhaps correct) way to trace back the idea of the origin of sentience. That somewhere (Freud’s *das ding*) there was a process situated at the start of being aware. And that (and Heideegger, too, took this path, to rather different ends…more on that below) there was some form of collective, of forms of collective turning away. A turn toward the kind of rationality humanity has practiced now for several thousand years. And by turning away is meant that there was an impulse (desire?, fear?) to cognitively distance oneself (sic) from this originary process of ‘being’. That man’s reflecting on himself in the act of reflecting was born in that moment — that process that also gave humans history and time.

Richard Wathen

Now what I describe as a turning away might, from another perspective, be a standing back in a collective. And herein lies the problem of metaphor again. This is also the beginning of theatre.

“Whereas the frontal lobes represent about 7 per cent of the total brain volume of a relatively intelligent animal such as the dog, and take up about 17 per cent of the brain in the lesser apes, they represent as much as 35 per cent of the human brain. In fact it’s much the same with the great apes, but the difference between our frontal lobes and those of the great apes lies in the proportion of white matter. White matter looks white because of the sheath of myelin, a phospholipid layer which in some neurones surrounds the axons, the long processes of the nerve cell whereby outgoing messages are communicated. This myelin sheath greatly speeds transmission: the implication of the larger amount in human frontal lobes is that the regions are more profusely interconnected in humans. Incidentally, there’s also more white matter in the human right hemisphere than in the left, a point I will return to.”

Iain McGilchrist (Ibid)

McGilchrist adds that what distinguishes us from the great apes, say, is our ability to stand back from our immediate experience ..

“This enables us to plan, to think flexibly and inventively, and, in brief, to take control of the world around us rather than simply respond to it passively.”

And that this is the result of the enormous growth of the frontal lobes. Well, except that’s not exactly it. There are a host of questions that arise here. Why the growth, evolutionarily speaking, of the frontal lobes? Like the appearance of stingers on jellyfish those many many millions of years ago. Evolution is a great mystery, and there are tantalizing bits of it, or bits of speculation, really, that carry their own poetics. As McGilchrist observes…

“ Many types of bird show more alarm behaviour when viewing a predator with the left eye (right hemisphere), are better at detecting predators with the left eye, and will choose to examine predators with their left eye, to the extent that if they have detected a predator with their right eye, they will actually turn their head so as to examine it further with the left. Hand-raised ravens will even follow the direction of gaze of a human experimenter looking upwards, using their left eye.”

Iain McGilchrist (Ibid)

One feels the superstitions about an ‘evil eye’ are somehow associated with this. More on this below.

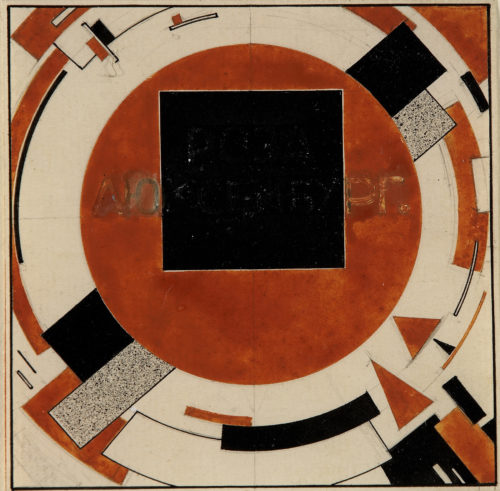

El Lissitzky, Design for Rosa Luxemburg monument . 1919 (pencil, ink, gouache on paper).

It is very interesting here to consider the role of language, then. McGilchrist suggests its possible that the right hemisphere (more below) might be the coordinating factor in sensory experience. The left hemisphere, on its own, might well behave like an octopus’ arm, wandering off separate from the brain, rather a roaming nervous system.

“There is no certainty. The more closely one pins down one measure (such as the position of a particle), the less precise another measurement pertaining to the same particle (such as its momentum) must become. It is not possible to know the values of all of the properties of the system at the same time. Mechanical systems, even at their simplest, are likely to produce highly complex outcomes. Not infrequently their behaviour is intrinsically unpredictable and unknowable (the simple double pendulum – one pendulum attached to the bottom of another – is a classical example of ‘chaotic dynamics’). ”

Iain McGilchrist (The Divided Brain and the Search for Meaning.)

And the left hemisphere, apparently, is the seat of close attentive processing of detail. And while sitting in the ICU today, and yesterday (to be moved on to a regular room tomorrow) I was pondering this pacemaker (or ICD) that was to be put in my chest somewhere. And such remarkable bits of tech force a moments pause criticizing technology. But this is significant, this pause. I think. Much of the best (not all, certainly) technology today is in the medical field. I am thinking of stuff like pacemakers, stuff that is very much a kind of hardware, a nuts and bolt solution to a problem. Much of the worse tech is purely useless. It is manufactured for profit. It is tied to marketing and advertising and it clear historical ideological weight. It is in the ‘reality ‘ business. Now, McGilchrist is not political except in that naive Carl Sagan sort of way. Not even that. In one interview he spoke of staring into a photo, a close up, presumably of Putin’s face. I have found in my long life countless examples of renowned scientists with this political naivete. They can, like McGilchrist, arrive at moral analysis of certain scientific problems (whatever that means, more below) but they do not consider political history. They do not factor in colonialism, or imperialism or capitalism. Most think socialism was horrible. Not all, since Einstein supported socialism. But you get the idea. There is not much their analysis of the material world that has a grounding in the history of social relations, or the history of societies. McGilchrist is, then, clearly not immune to the forces of capitalism. To the Spectacle.

Tintoretto (Origin of the Milky Way, 1575)

Now, sidebarring a moment here (it’s a verb now) I want to mention a painter of the Renaissance that I was looking at this week; Tintoretto. And Tintoretto is much neglected, actually. He was self taught, from a working class family, at a time when the arts, especially painting, had dramatically appeared in Venice culture. Titian was the leading figure, but close behind, for a while, was Veronese. Tintoretto learned of paint from working in a factory painting furniture. (His father was a cloth dyer, working at a tintore). He never changed his nickname. Tintoretto, christened Jacopo Robusti, embraced his lower station pedigree. And he developed greatly over his career. By his mature period it is hard to not see a precursor to Rubens or even Delacroix. Tess Thackara wrote, quoting Tintoretto specialist Frederick Ilchman:

“Tintoretto’s ability to work quickly was matched by his considerable aspirations and energies—even as he associated with the city’s poor, holding onto a working-class nickname while other artists upgraded their names to appear more aristocratic (Veronese, for instance, adopted the name of a noble family, Caliari). Tintoretto’s “impulse toward the gigantic, his overwhelming desire to create enormous paintings that would dominate prominent public places” was fundamental to his identity, according to Echols and Ilchman. Indeed, a playwright once wrote a note to the young Tintoretto, testifying to his largesse: “Your personality is so big despite your small stature that you’re like a single peppercorn that takes over the flavor of a whole dish.”

Tess Thackary (Tintoretto Was the Unsung Hero of the Venetian Renaissance)

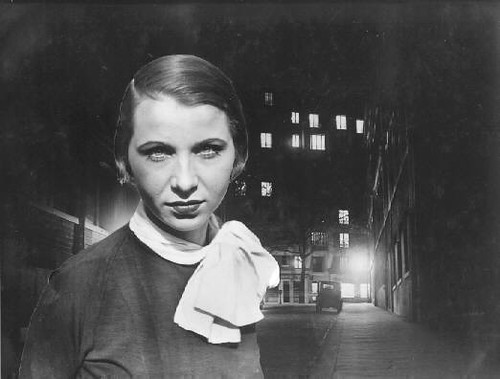

John Vanderpant, photography.

Tintoretto, and the Venetian school of the Renaissance are fascinating for their air of poetic fluency (and remarkable use of colour). What Tintoretto took from Michelangelo was not the technique (though he did take the compositions often) but the spirit of transcendence. Raphael, the most technically fluent of the Renaissance, in the minds of many (or Michelangelo) was austere by comparison. So was Botticelli. They both had their own perverse sense of theatrics, but in Tintoretto you find something more earthy and maybe even tragic. There is also in Tintoretto (and it’s true in another way in Veronese, and Michelangelo, certainly) a sense of the supernatural or mystical. The allegorical richness of Tintoretto, in particular, is almost overwhelming.

So let me return to McGilchrist, and again to Wittgenstein. And to language.

“Although ‘seeing clearly’ is an image of grasping the truth, there is no such thing. At what level of magnification, at what level of description can you be said to have seen something clearly.”

Iain McGilchrist (The Divided Brain and the Search for Meaning)

This remark, almost an aside, really, encapsulates the problem I am trying to point to. McGilchrist keenly notes, without exactly saying so, that certainty is an illusion, or rather it is more allegory. This also relates to Wittgenstein’s quote at the top of the page. So much of how and what we think is just the scaffolding we have inherited. And without which one would sink into a miasma of logical cul de sacs. You cannot question literally everything. Wittgenstein’s collection of notes, published under the title On Certainty, were the final writings of his life. In some respects they may be the most profound.

Josef Breitenbach, photography (Paris, 1935).

“The sorts of truisms that the Sceptic claims to doubt and Moore claims to know cannot normally be doubted; but for that very reason they cannot be said to be known either. They function rather as assumptions which establish the framework for our thinking. When we claim to ‘know’ something, we do so in contexts where there is a point to the claim, that is, in a situation where it might make sense to doubt it.”

Anthony Rudd (Wittgenstein, Global Scepticism and the Primacy of Practice)

This debate about what we know to be ‘real’ is, in Wittgenstein’s mind, a misuse of language. Yes, in a certain context we can say we know we have two hands, or that there is a glass of water on the table. But it confuses the issue to extrapolate from this anything like knowing wider or deeper explanations for these ‘facts’. Here language intersects, or rather how we ‘use’ language. Metaphysical disputes cannot be settled on an empirical level. This is a very important observation.

Rudd adds; “Sceptical doubt would undermine the Sceptic’s understanding of the meanings of the very words she uses to express that doubt.” This is Wittgenstein’s idea about usage. That grammar must be investigated.

“Doubt itself rests only on what is beyond doubt.”

Wittgenstein (Ibid)

This is one of the starting points for what has happened to much of western society today. Ideas of skepticism have almost been placed in abeyance. And beyond that, the ability to think logically has been eroded. Here is an good example of how Wittgenstein sees ‘language games’.

“For example, if Neil, a competent English-speaking member of twenty-first-century western culture, goes for a medical examination because of some odd pain in his hand, he may describe his pain as pounding, dull or sharp, and he may locate the pain in the bones, in the muscles or on the skin. Being unable to relate Neil’s descriptions to a medical sample, his physician may ask him to explain what he means by ‘sharp’ or ‘in the muscle’, and she may insist on further description and clarification. But if she asks Neil what he means by ‘a hand’ or ‘pain’, she will then be questioning his English speaking competence and/or his ability to identify pain. That is, she will have ‘switched to another game’, and the problem will have changed from attempting to find out the cause of Neil’s pain to testing whether or not Neil is able to communicate in English, or altogether.”

Michael Kober (In the Beginning was the Deed’: Wittgenstein on Knowledge and Religion)

Piet Mondrian

For the purposes here, this is almost a sidebar. But it is useful to bear in mind, I think. Wittgenstein thought we are born into specific cultural practices. And we cannot wholesale dispute the entirety of our culture.

“What Wittgenstein disliked was not science and technology ‘as such’ – remember that he once studied engineering, and that he never lost interest in mechanical devices – but a scientistic stance that assumes that everything valuable in human life can be explained scientifically and thus controlled technologically. For Wittgenstein considered religious or mystical aspects of human life to be worthy of philosophical clarification. Understanding the religious stance will help us better understand the category of certainty.”

Michael Kober (Ibid)

What one sees today (Climate Change, for example) are violations of the values and beliefs a community shares. There are no community discussions, no Town Hall meetings. There is only corporate control of message. I think it is useful to remember the cultic practice today of the true believers for climate change or Covid or transhumanism et al. In fact, as I, or someone else said, capitalism itself is a religious cult.

“Correspondingly, the leitmotif of the Remarks on Frazer’s ‘Golden Bough’ consists in Wittgenstein’s insistence that religious or mythological narrations should not be understood as true or false reports of what actually happened. Rather, they should be looked at as apparently theoretical ‘devices’ on which members of a cultural community agree: these narrations serve as a platform which shapes and belongs to a community’s cognitive world-picture. They motivate their members’ non-cognitive stance towards the world and human life, and they function as the ground where explanations indeed come to an end. Accordingly, a religious stance may be shown by manifestly protecting our natural environment (cf. ‘preserving the Creation’) or by standing up for other people’s dignity.”

Michael Kober (Ibid)

Egyptian. Third Intermediate Period, circa 1070–664 BC

And it is here that McGilchrist starts to sound very Wittgensteinian.

“An important consequence of this narrow-focus attention, aiming for certainty, is that it renders everything explicit. Just as a joke is robbed of power when it has to be explained, metaphors and symbols lose their power when rendered explicit. And metaphor is not a decorative turn, applied on top of the serious business of language in order to entertain: all thinking, most obviously philosophical and scientific thinking, is at bottom metaphorical in nature, though we are so familiar with the metaphors that we don’t notice their existence. It is the metaphors which provide the ‘something else’ which we know more intimately from our embodied, preconceptual experience, and to which we are, in every word we use, properly understood, making a comparison.”

Iain McGilchrist (The Divided Brain and the Search for Meaning)

So, the left hemisphere of the brain is removing that ground, the foundations of meaning, which the right (more or less) provides. We are increasingly relying, societally, on left side thinking. Which is not strictly correct, of course. But not wrong, either. And here again, looms the political. What is often missing in discussions with scientists is that the political now operates in the realm of propaganda.

“People whose minds have been influenced in this way typically have never felt more themselves, while in truth the self they are imagining they are is an artificial simulation of themselves—an imposter—that they have taken to be themselves. They have unknowingly fallen under the spell of “the counterfeiting spirit” of the Apocryphal texts, which “puts us on,” (i.e., fools us), as it impersonates us—we then become impersonations of what it is to be a human being. People who have been sufficiently propagandized are living in the self-reinforcing echo chamber of their own programmed and stunted imagination, a limited, self-blinding and crazy-making scenario which they themselves are unknowingly buying into and thereby perpetuating in each and every moment.”

Paul Levy (Invasion of the Body Snatchers Comes to Life)

This feels related to the Capgras syndrome written about above, only inverted and turned inward. One interesting aspect of Capgras syndrome is the semantic element in how the patient ‘reasons’ about his problem. The language of the sufferer, the grammar he has inherited, does not allow for ‘irrational’ explanations (!). Here the idea of explanation requires some investigation. And this is really the entire point, actually. Science has become a new religion. Or, it is a sect in the cult of Capitalism. And the grammar of science has gone through several incarnations over the last fifty years, and is now very close to advertising copy.

Egyptian mummy mask. Wood 1295-1070 bc (Courtesty of Kallos Gallery)

“For the majority of adolescents, but not only adolescents, communication takes place largely through digital networks, with others or an other, who is not physically present, yet whose physical absence is tied to a virtual permanence.In a peculiar way, the other is always and never there. There is a permanent connection to physically distant people, whose perpetual medial presence is a virtual precondition of the connection, though it is not necessarily or, in fact, continually guaranteed – like a person lurking in the background, who may or may not be watching.”

Vera King ( ‘If you show your real face, you’ll lose 10 000 followers’ – The Gaze of the Other and Transformations of Shame in Digitalized Relationships)

Magical beliefs such as the Evil Eye usually entail a sexual component. And protection from such magic takes the form of counter sexual symbolism (turning the rear end of the baby toward the eye, imitation of masturbation, etc). In Italy, of course, there are also the hand gestures, profoundly coded, the mano cornuto (often seen as just the sign of the horn but actually an entire system of intricate hand gestures). And the evil eye appears in Mexico and Central America still, the mal de ojo, and animal eyes are often substitutes on both the evil side and the side of protection. But the point here is the immediacy of these practices. You cannot cast spells on the internet.

Franz Von Stuck (Wild Chase, 1889).

{ side bar: the above painting by German symbolist Franz Von Stuck was painted the year Hitler was born. It was a fave painting of the Führer. The central figure, meant to be Woton, looks like Hitler. Make of all this what you will.}

Magic is always sensual, somehow, even spells cast at a great distance. And perhaps this is a key aspect of what has been lost in digital culture. I think, however, that it is too easy sometimes to just denounce screen technology. I think there is a profound potential for organization and sharing of information. But not with the platforms developed in the laboratories of Capitalism. I have read that the categorical imperative of our times is ‘Be entrepreneurial’! And this is obviously categorically not true. This is part of the mystification of the entire social media marketing

“For without the gaze of the other, the child’s world remains empty and their psychological development is impeded. This is how the Subject affirms itself in the eye and gaze of the other, the one who “sees and recognizes”,who gives affection and affirmation. For the self, this gaze of the other bears important emotional consequences.”

Vera King (Ibid)

King adds a moment later : “As M. Lewis (1992) maintains, guilt is characteristic of a competitive, individualistic, capitalist society, while shame takes on a particular, even regulatory function in precapitalist, ethnic and traditional societies.”

Shame is, conventionally seen as a discrepancy between the *I* and the ideal *I*. And guilt as a discrepancy between the *I* and the super ego. (which King notes). What King is suggesting is a transformation of how society treats shame. And for children, without the necessary affirmation, found in the look from the parent, there will be a deficit in their developmental process for individuation. A deficit in the ability to navigate emotions associated with guilt or shame. And with self worth.

Juan Jose´ Cambre

“The left hemisphere is not in touch with reality but with its representation of reality, which turns out to be a remarkably self-enclosed, self-referring system of tokens.”

Iain McGilchrist (The Divided Brain and the Search for Meaning)

The internet, under Capital anyway, is a left hemisphere world. The right hemisphere is relational. It has a connectedness to the ‘real’ world. The left has a relation to a representation of the world.

“both hemispheres are involved in reasoning and in emotion. The left hemisphere is especially good at voluntary and social expressions of emotion and one of the most clearly lateralised emotional registers is that of anger, which lateralises to the left hemisphere. Deeper and more complex expressions of emotion, and the reading of faces, are best dealt with, however, by the right hemisphere. ”

Iain McGilchrist (Ibid)

This begs a dozen questions, of course. Like defining the baseline meaning of, say, anger. Also semantics again intercedes. And magic. Also, what understanding means (Gilchrist notes this) in terms of say, aesthetics and the arts vs *science*. It is not just the digital world that feels left hemisphere dominant. The political world does, too. Writing of the left hemisphere…

“It is not reasonable. It is angry when challenged, dismisses evidence it doesn’t like or can’t understand, and is unreasonably sure of its own rightness. It is not good at understanding the world. Its attention is narrow, its vision myopic, and it can’t see how the parts fit together. It is good for only one thing – manipulating the world.”

Iain McGilchrist (Ibid)

So, the neuropsychiatrist and the neuroscientist seem not to analyse anything from an actually historical/social perspective. Ramachandran mostly not at all. McGilchrist does, but its very basic stuff. Mark Posner tells a remarkable story about the telephone company and a system of service that existed long ago, in my childhood. It’s a long story so I will only share a part of it.

“When I was quite young, my father had one of the first telephones in our neighborhood. I remember well the polished old case fastened to the wall. The shiny receiver hung on the side of the box. I was too little to reach the telephone but used to listen with fascination when my mother used to talk to it. I discovered that somewhere inside the wonderful device lived an amazing person; her namewas ‘‘Information Please,’’ and therewas nothing she did not know. ‘‘Information Please’’ could supply anybody’s number and the correct time. My first personal experience with this genie-in-the-bottle came one day while my mother was visiting a neighbor. Amusing myself at the tool bench in the basement, I whacked my finger with a hammer. The pain was terrible, but there didn’t seem to be any point in crying because there was no one home to give sympathy. I walked around the house sucking my throbbing finger, finally arriving at the stairway. The telephone! Quickly, I ran for the footstool in the parlor and dragged it to the land-it to the landing. Climbing up, I unhooked the receiver in the parlor and held it to my ear. ‘‘Information Please,’’ I said into the mouthpiece just above my head. There followed a click or two, and a small clear voice spoke into my ear. ‘‘Information.’’ ‘‘I hurt my finger . . .’’ I wailed into the phone. The tears came readily enough now that I had an audience. ‘‘Isn’t your mother home?’’ came the question. ‘‘Nobody’s home but me,’’ I blubbered. ‘‘Are you bleeding?’’ ‘‘No,’’ I replied. ‘‘I hit my finger with the hammer and it hurts.’’ ‘‘Can you open your icebox?’’ she asked. I said I could. ‘‘Then chip off a little piece of ice and hold it to your finger,’’ said the voice. After that, I called ‘‘Information Please’’ for everything. I asked her for help with my geography and she told me where Philadelphia was. She helped me with my math. She told me my pet chipmunk that I had caught in the park just the day before would eat fruits and nuts.”

Mark Posner (Information Please: Culture and Politics in the age of Digital Machines).

Sascha Schneider (1904)

“Briefly, ego psychology altered psychoanalytic theory by diminishing the importance of the instincts, marginalizing the role of the unconscious, stressing position of the ego, and introducing a new preoccupation with social aspects of individual psychology. Each of these revisions of psychoanalysis contributed to the emergence of the question of identity.”

Mark Posner (Ibid)

Posner to his credit does discuss language; the evolution certain terms, but it also inadaquate.

And here is most significant problem (shared by more than just Posner):

“A decade or two later, artists have become far more sophisticated in the application of computers to art projects. Above all, recent installations employ not stand-alone computers but networked computing. The installation is displaced into cyberspace as well as embedded in traditional sites. An exhibit at the Centre Pompidou in 2001 by George Legrady illustrates the new configuration of aesthetics and politics in relation to the media. Legrady’s installation Pockets Full of Memories calls for visitors to input in digital form some object they regard as important. Visitors to Beaubourg are greeted by a phalanx of scanners, machines that enable the digitization of any object in the visitor’s pocket that may be significant, loaded with memories. Those attending the exhibit via the Internet may upload images from their computer. The visitor may also add text to the image of the object. These inputs are composed by the computer into a database. After so contributing to the work of art, the visitor passes, by foot or, if online, by computer, into a room with a large wall on which the digitized objects appear…”

Mark Posner (Ibid)

etc etc etc. But I trust the point is clear. This is not art. I guess you call it bad art. And someone as credentialed and respected as Posner should most certainly know better. And nary a mention of the economics of the gallery system, the privilege of certain University programs; essentially the class analysis of culture and the arts.

Paolo Gasparini, photography.

Class is never taught in North American schools. Very few of the so called post colonial studies include class. And some of the authors taught in those studies are very good. But identity has utterly eclipsed class. And Posner does provide a pretty cogent chapter on identity. Much of it is devoted to ‘identity theft’, which while interesting is not quite the topic here. Although it does in one way link up with Capgras Syndrome.

“The venerable OED says of identity that it is ‘‘the sameness of a person or thing at all times or in all circumstances; the condition or fact that a person or thing is itself and not something else; individuality or personality.’’ The OED definition harks back to Aristotle’s logic of the excluded middle: that a thing is what it is and not what it is not. To have an identity means that one cannot at the same time and in the same place be what one is and what one is not. But the OED goes beyond classic Western logic to a more modern sense of the term that is psychological in nature. It speaks of ‘individuality or personality’. The dictionary provides a psychological definition of identity as ‘the condition or fact of remaining the same person throughout the various phases of existence; continuity of the personality.’ In the move from logic to psychology, identity becomes an attribute of consciousness.”

Mark Posner (Ibid)

This is a pretty insightful observation. Posner adds, looking back…“Status, kinship, métier, and place defined individuals in early modern Europe.” The psychologizing of the definition of identity left open a move to create identity. Be Entrepreneurial! But the creation of identities (separate even from the information data definition, which still exists in a crypto fashion, the shadow meaning of identity, operative for the authority structure). Posner makes a few odd outright mistakes in this chapter. Suggesting (he uses Locke) the Cartesian worldview where everything is in its place and stays in its place. Posner suggest identity does not stay in place if you include *time* (along with space and matter). Because, he says, things deteriorate. Well, uh, yeah. Nobody said identity was eternal. Locke focused a bit on ‘continuity’ but only abstractly (see the riddle of the Ship of Theseus). That said, Posner rightly notes Locke’s definition of identity, which includes the *recognition* of sameness. In other words a conscious recognition.

Sam Gilliam

“This may show us wherein personal identity consists: not in the identity of substance, but, as I have said, in the identity of consciousness.”

John Locke (Treatise of Civil Government and A Letter concerning Toleration, 1689)

Identity is an element of consciousness. It is important to note that Locke also saw property as an element of identity, and that his identity owned the land tilled by others. All part of who he was. Now, Posner uses Erik Erikson as his model for ego psychology. Ego psychology was the result of psychoanalysis crossing the Atlantic and de-emphasizing sexuality and especially the unconscious. And it’s subsequent medicalization. The search for truth gave way to a class mediated notion of adjustment. Posner is saying something different, in one sense, but that’s because he never includes class in his analysis. Erikson saw identity as ego identity — which he defined in terms of sameness to others, sameness to oneself. Like Locke he felt continuity was important. It is interesting that Erikson was so embraced in the U.S. He became the voice of social adjustment. The voice of the status quo (Norman Rockwell was a close friend and patient). But it always struck me that there was a lingering oddness in Erikson, and his emphasis on social expectations. And the values of the society in which the child and adolescent are raised. It is really rather reactionary finally, which accounts for his popularity (and like Jung, is tall and blond). His idea of ‘social’ was submission to whoever was in power.

“The American discourse on identity, by dint of the popularity of Erikson’s writing, reinforced the Lockean version of identity as consciousness.”

Mark Posner (Ibid)

The goal is a mass produced personality. And that personality is one’s identity.

Keith Haring

An awful lot is made about internet deceptions, impersonations and identity fraud. But the more I read about it the more banal the entire question becomes. People have deceived each other and impersonated each other since the dawn of history. Read Shakespeare’s comedies. Read Jacobin revenge drama. Read Patricia Highsmith, or Chaucer’s The Pardoner’s Tale. Or Dumas. Or The Scarlet Pimpernel. Or hell, Zorro. I mean this is actually rather a staple of Hollywood film. But this speaks to the mystifying qualities of digital media, and also the sub-literacy of most Westerners today. People used to impersonate other people on telephones. Or hey, how about Cyrano de Bergerac. There is nothing unique in social media relations other than the damaged psyches of contemporary westerners. And the fact that internet platforms are designed, firstly for profit. And secondly are designed by, I can only infer, sociopaths. But then sociopathology tends toward the maximizing of profit. Capitalism is a system in which sociopaths flourish (Bill Gates, Bezos, Musk, et al). And the political class today are really just the representatives of Capital. They do the bidding of those who financed their run for office. At the top of the list of financiers is the Defense Industry. And it is delusional to imagine this ruling class wants anything but absolute power. They do not want to help the most vulnerable, they do not want to find solutions to housing and the mental health crisis (including addiction). They spend most of their energy manufacturing propaganda.

The screen habituation today has had significant effect on the mental health of the population. But the problem, I don’t think, lies entirely, or not nearly entirely, because of some inherent quality of screen communication (sic). It lies in the intentional design of this technology, the software. And that design, given the pre-existing psychological conditions of the populace results in a further distancing from one another, a further fragmentation of community, and a further (per Debord) generalized autism. And many (not nearly all) the critiques of digital media tend to utterly forget the Capitalist engine in all this, and that it is not hard to imagine programs and platforms designed NOT to addict and numb.

Now, this is a large topic here, and I suspect there ARE aspects of screen use that are psychologically damaging no matter who designs them. But that is for another post. A final few words on Wittgenstein, because I believe philosophy is part of the cure to the current madness. And that would begin with learning to think again. And that in turn begins with language.

Tintoretto (study after michelangelo’s Giorno) 1550

I start with a final (almost) quote from Posner:

“The body is here understood as represented in the discourse of medicine through the gaze instituted in the early clinic; as a surface of desire inscribed upon, absorbing impressions, yet in the end undeterminable and capable of forming new patterns of energy and intensities; as gendered by binary heterosexual practices…”

Mark Posner (Ibid)

This is just gibberish. Literally meaningless. Gender is binary by the by. That paragraph continues but I won’t bother quoting it. Some of the sentiments are right (the marginalized are brutalized, but why not just say that instead of couching it in the language of postmodernism? Posner then goes on to parrot the usual anti-Freudian criticisms. It is in this chapter I wanted to scream, just read Wilhelm Reich. Also a critic of Freud, but for very clear and defensible positions. And here, with Posner, comes the veiled (thinly) criticism of breast feeding. This is actually a part of the war on the human, not its rescue.

“Yet when writing about the basic formation of the personality, Freud gives overwhelming attention to living adults. He constructs the emotional universe of the child as consisting of adult characters who are the parents of the child.”

Mark Posner (Ibid)

Well, uh, yeah. The fact that today children are developmentally retarded by being handed off to smart phones and iPads is a political discussion. But the fact that technology plays a bigger role in childhood development does not mean Freud was wrong. Posner notes that practices like breastfeeding, toilet training, and sexual prohibitions have all changed, but he NEVER ONCE questions why they have changed? He also adds few asides about the outdatedness of Marx. Never mind.

“But when is something objectively certain? When a mistake is not possible. But what kind of possibility is that? Mustn’t mistake be logically excluded?”

Ludwig Wittgenstein (On Certainty)

This short three sentences is exactly why Wittgenstein should be read and studied by all postmodernists. The growing incoherence of Academic jargon is akin to a virus. There is also an increasing sense of an oppositional subjectivity that feels very much a product of late capitalism (and the left hemisphere). Social media encourages negative emotions. It encourages pointless argument (though this needs little encouragement today). And this has bled into social relations in the West as a whole. The degrading of language has, as noted above, caused an increase in gibberish, but it has also (along with social distancing) eroded people’s ability to talk to each other. There is the disappearance of the undecided. (Left hemisphere again). The argument must have a resolution. Either white or black. It is very hard for people today to analyse the question, the argument if you will, and suggest perhaps this is a non-question. Is global warming man made? Well, I don’t see evidence that it is. If you show me computer models I will launch into a discussion of the unreliability of such models. If you ask is the earth getting warmer? I suggest we cannot finally know. Maybe it is, and maybe that will become clear, but it’s not clear at the moment. I would argue in a sense, these are at bottom, non questions. What is evident, I believe, is massive pollution, and massive deterioration of infrastructure and massive and growing economic inequality, and a continuing escalation of militarism, almost exclusively from the U.S. And I think those beliefs are very easy to prove.

Michelangelo (Mask, representing Night, lid of the sarcophagus of Giuliano de Medici) 1524.

But the sense of belonging has also eroded. There are clearly many people today who do not succumb to the propaganda. Not entirely anyway. And certainly in the Global South there is a growing resistance to American domination and ideology. But there in the West, there remains a huge mass of the population who will insist that Capitalism is the best system even as take their Zulresso or Zoloft. The disconnect is very deep now. And digital tech, most especially mobile phones, have taken on fetishtic aspect. And this is where digital meets magic.

“The mobile in all its rewarding tactility and controlled aesthetic frames becomes the place where excitation and apprehension (erotic and intimate) can be experienced and shared (e.g. via sexting and photography) at the expense of other connections and channels. The risk evoked is that some degree of the experience of real, intimate, messy and risky human relating is foreclosed in favour of a fixation privileging the mobile screen.”

Iain MacRury/ Candida Yates (Framing the Mobile Phone: The Psychopathologies of an Everyday Object)

But this is an artificial magic in some sense. For it is magic that delimits the imagination. And it supports the avoidance of emotional complexity — the cult of agreement.

“For, at some point, he or she, or the others, will, perhaps, read the message, look at the posted photos, the selfies and posts, or the text messages and emails, or follow the Twitter messages, hashtags and endless stream of communications in the various Whatsapp groups – all the things that happened while you slept or had to ‘tune out’ for a second to watch for cars as you crossed the street. But, sometimes the other(s) might be looking at the very moment “I” am writing. “Are you there?” is the typical call…”

Vera King (Ibid)

“Sleep is dear to me, and even more so to be stone,

As long as ravages and shame endure;

Not hearing, not seeing is my greatest chance,

Don’t wake me up, oh! talk low!”

Michelangelo

To donate to this blog and to the Aesthetic Resistance podcasts, use the paypal button at the top of the page.

You must be the world’s fastest reader, or most voracious. I’m still working my way through The Matter with Things. The current chapter I’m reading is on intuition, which, unsurprisingly, bureaucratic culture is suspicious of and considers unserious. McGilchrist’s take on this, that our knowledge is greater than we realize (he speaks a bit about the “brain” in the gut) is ignored like how brain studies show how someone with damage to the right hemisphere who lost a limb insists that it is still there. A lot of implicit politics there.

I grew up in South Philly and when people would compliment another person they were careful not to give them the maloiks (Mal’Occhio… the Evil Eye). You’d say, ”that new car is beautiful Joey. God bless.”

So, god bless and get well.

thanks david. And I am a lot of time to read sitting here in my hospital room.

This one mentions something I’ve noticed in a lot of shit art, some of it looks like it has no world to it… “views from nowhere”

A lot of the abstract art you put in your articles suffers this too…

From The Matter with Things by McGilchrist:

“A distinction has repeatedly been made between the right hemisphere’s capacity to identify the location of something in the depth of space, its ‘co-ordinates’, so to speak, and the left hemisphere’s strategy of categorising something as ‘above’ or ‘below’ something else.39 The right hemisphere’s organisation of space depends more on this sense of where things are, nearer or further ‘from me’ – on depth, in other words.40

The left hemisphere has a problem dealing with depth, whether that be depth in space, in time or in emotion.41 And, as far as spatial transformations go, it is not just that three-dimensional depth is lost and objects appear flattened; they also become more distanced, more generalised, more stylised, less fluid, more symbolic and more geometric. This strange visuo-spatial world is sometimes dramatically obvious after a right hemisphere stroke. The sense of overall shape, the Gestalt, may be lost, reduced to an aggregate of details without form; and with that the vital flow is lost. In general, drawings by the isolated left hemisphere show important characteristics of a virtual, rather than a real world image, or, as we might now say, an ‘icon’, rather than what that icon stands for in the lived world. They become ‘views from nowhere’.42”

well, just an observation….but I’m not sure a lot of abstract art is meant to be from ‘somewhere’ (in your context). If you look at aboriginal art, for example, there is a clear sense of being planted in the earth somehow. Color field is always the stuff that gets criticized. But Barnett Newman remains a favorite painter of mine (he is often associated with ab-ex). Kenneth Noland not so much and i love noland. But there is a lot of bad abstract work…what got the name Zombie Formalism. https://aestheticsforbirds.com/2019/07/31/zombie-formalism-or-how-financial-values-pervade-the-arts/ (first coined by walter robinson I think). But i try not to post zombie formalism. Is that thomas nagel you quote from? Anyway….i think more insidious is stuff from Hollywood. Things mediated by CGI. Where the real world is actually almost literally being erased.

Dios Mio. Get well soon! We need (among other things) the People’s University…

and, as to reading, I’m still struggling with Adorno, and probably will be for life. haha.

I apologise if the following remarks seem a bit disjointed. I assembled them as reactions to this article and even tried posting some of this before but got halted by this strange CAPTCHA software which makes insertion very much a wing-and-prayer matter.

There’s certainly plenty of, to be charitable, naivete in that fabled “scientific community”, Sam Harris being a particularly irksome example though to be sure he is a repellent shill for the US Empire. Dawkins is slightly more nuanced though his tirades against religion display that crude Either/Or duality which ironically reproduces the fundamentalist Good/Evil of the ones he rails against. (His oxymoronic “selfish gene” mirrors their idolatry.)

The attack on certainty recalls much of what Nietzsche said about convenient illusions. Perhaps he was the originator of this line? But then it was already there in embryo from Schopenhauer and, before him, Kant.

“What one sees today (Climate Change, for example) are violations of the values and beliefs a community shares. There are no community discussions, no Town Hall meetings. There is only corporate control of message.”

That’s a powerful indicator of a change in media discourse so deep and ominous that it has totally bypassed the consciousness of most people. Media was always molded by the powerful. But there was a certain leeway permitted – necessarily so since, up until recently, it was acknowledged (from those above) that a totally controlled media would be incapable of fooling anyone. There had to be the appearance of a plurality of opinion. And the appearance could only be effective if there was, up to a point, ACTUAL plurality of opinion. Thus there was always a tension between what the rulers had to permit and what they really wanted the media to say. In other words, there had to be a token allowance of community discussions and Town Hall meetings whilst the rulers struggled to exert as much corporate control of message as they could get away with.

In this model, there developed a situation in which dissenters could work with various levels of awareness of how much they could achieve within this tense framework.

But all leeway has disappeared. No more token allowance of community discussions and Town Hall meetings. The rulers have now brutally asserted corporate control of message. The appearance of discussion and meeting has been insultingly packaged as a display of infantile designated protest groups, oxymoronic transgender blather, citizens dourly concerned with blatantly artificial “catastrophes” etc. Even the appearance of opposition is no longer tolerated and only manifests as a vague off-stage murmur of menacing “reactionary” forces.

And the biggest problem is that massive numbers have no idea that this has happened. They gravitate, under pressure, to the sanctioned views with a deep unease that they are being duped but genuinely terrified to admit that the world they knew has gone. The only views they are permitted are precisely those asinine woke mantras used to further the power of the corporate controllers.

In short, the public has effectively been ejected from even an appearance of democratic involvement. But the hope lies in the fact that it is still the case that a totally controlled media would be incapable of fooling anyone. And it only appears to do so right now because it hasn’t happened before in our lifetimes. This new totalitarianism has a “sell by” date. The rulers know this. The public are beginning to realise it. The real question is: What comes next when the illusion no longer fools anyone?

And just to end on an unrelated note (but I don’t know who to turn to anymore), I have had it with the “Marxist evacuation” from the sites that are honest enough to face up to the frauds of the new “covid world” i.e. sites like Off Guardian who have provided a touchstone to a genuinely critical voice but at the expense of throwing the door open to non-Marxists who are obsessed with the notion that we are facing some kind of “creeping” or “accelerating” communism. It is so exasperating to continually read the kind of Right Wing fixation on “Marxist takeover of the West” etc.

A couple of thoughts upon reading, in no particular order:

The Iain McGilchrist quotation regarding how jokes lose their meaning when they have to be explained has taken a pandemic twist: jokes lose their meaning when the facial expressions necessary to signal humor are blocked by mandatory masking.

Richard Power’s The Echo Maker has an interesting depiction of an Oliver Sacks-like character as well as Capgras syndrome.

I’ve been searching/not-searching for a left-right brain explanation that would help me navigate the physical symptoms I’ve been experiencing on my left side. As you may know, the right side of the brain controls the left side of the body. What you’ve offered here helps tremendously especially as it relates to the pandemic trauma of the right hemisphere’s ability to recognize faces and process information intuitively and perhaps, reaching further back, to the unhealed trauma of my training/escape from academia.

Finally, having been publicly outed at the tender age of 17 as an Mal’Occhio by a high school teacher, I’m here to say that it’s been a true blessing to look sideways at this effing world.

Being there…

Yes, John, take good care of yourself. I could

not conceive of conscious life without periodic

exposure to your exegeses. If that sounds like

a selfish motive, I’ve had a seismic identity crisis

since my massive right brain stroke & have a

subsequent evil left eye overgrowth.

With respect to the last comment, I always prefered

Flo to Downtown Abbey because of my pronounced

plebian inclinations. And I agree that much

more can be found in Nietzsche than in all of

post-taylorist, post-fordist sciencef

haha thanks Tamara. Really good point on the mask wearing and jokes.

Very interesting. I just listened to your podcast. You had on a bestselling leftist journalist and expert on carbon-driven climate change and the politically urgent need to drastically reduce emissions: Christian Parenti, author of the excellent Tropic of Chaos; Climate Change and the New Geography of Violence.

In his book he writes frankly:

” Any heating beyond 2°C will likely cause catastrophic changes, transformations too sudden and radical for civilization to cope with. The 2°C threshold runs throughout the most recent reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), and it is the official stabilization target of numerous governments and the European Union.9

The question then becomes, What is the corresponding limit on atmospheric concentrations of CO2? For years it was assumed to be around 450 ppm. To meet this goal, the IPCC recommends that developed countries reduce their greenhouse gas emissions to about 40 to 90 percent below 1990 levels by 2050. This would require global targets of at least 10 percent reductions in emissions per decade—starting now. Those sorts of emissions reductions have only been associated with economic depressions. Russia’s near total economic collapse in the early 1990s saw a 5 percent per annum decline in CO2 emissions.10

Calculations by the United Kingdom’s Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research demonstrate that, without radical mitigation efforts, we are almost inevitably on course to reach atmospheric CO2 levels of 450 ppm. Even with drastic emissions reductions over the next 20 years, cumulative atmospheric CO2 could easily surpass 450 ppm.11 If that’s not grim enough, James Hansen of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies at Columbia University now believes the tipping point at which climate change becomes a runaway, self-fueling process is closer to 350 ppm. We are already at 390 ppm.12 In terms of adaptation, that would mean we must prepare to deal with a 4°C increase in average global temperatures and the massive social dislocations that will bring.”

These latter “social dislocations” include:

“With the rise of capital-intensive cotton farming in Telangana over the last thirty years, two strange contradictions have arisen.40 First, the primary cash crop, cotton, continues to decline in value; yet, farmers continue to plant more of it. Why do the farmers not shift to other crops? Second, while the region’s overall growth in agricultural output has been robust—more than 4 percent per annum for many years—the incomes and consumption of most farmers have declined precipitously, and this manifests as farmers’ suicides and support for the Naxals.41 The question now becomes: Why do farmers go into debt so as to plant a crop (cotton) for which the price is falling?

A brilliant young economic historian, Vamsi Vakulabharanam, has identified and explained the politics of this contradictory, seemingly nonsensical set of facts. The answer, he writes, lies in the credit system. The moneylenders demand that cotton be planted with their capital because cotton is inedible, so during times of crisis, producers cannot “steal,” that is eat, it. Moneylenders essentially give advances on crops, then receive the harvest. If a farm family is dying of hunger and their crop is grain, chances are they will eat the collateral crop to stay alive, rather than give it to the moneylender. Cotton avoids that problem. Thus, even when food crops, like grains, command higher prices, they carry greater risks for the moneylenders. Cotton is the moneylenders’ biological insurance; they steer farmers away from food crops, even if the potential for profits is higher, because only cotton is guaranteed collateral. Using this insight, Vakulabharanam shows that since 1980, farmers in Telangana have moved away from planting coarse grains, like jowar, barley, and millet, toward growing cotton, even as the price signal should have them doing the opposite.

This shift has coincided with the neoliberal reforms that removed from agriculture many legal protections and government subsidies—including public credit and public investment in irrigation.42 In response to the relative withdrawal of the state, farmers took on more expenses themselves and, in turn, had to raise capital wherever they could—that meant from moneylenders. The more farmers turned to private moneylenders, the more they were under pressure to grow more cotton. And the more cotton they grew, the lower its price sank.

Thus, Telangana farmers become trapped in a downward economic cycle: they need expensive inputs and capital to produce a crop that drops in value even as they invest more heavily in it. And the central equipment—especially as climate change makes the region drier, due to extreme weather and frequent drought—are the well and irrigation systems. So, the farmers borrow. Vakulabharanam calls it “immiserizing growth”—agricultural output rises but incomes sink. Others have described the same set of contradictions as “modern poverty” or a form of “development-induced scarcity.”43”

I was looking forward to the debate but it turns out it was a frictionless encounter, steering clear of any contentious subjects, like the resurgence of Maoism and the imminent demise of civilization due to global warming. You avoided all disagreement or debate by focusing on the common hate figure of ‘diversity’ and affirmative action in bourgeois professions (Entertainment, Academia, Politics). That is really a shame, I hope you will have him back on so you can confront him on this matter, and give him the opportunity to respond.

Christian’s most recent article was on diversity. And he was one of the few to write on Covid. So that was the starting point. Nobody ever said it was a debate. I think he intends to return, and I’m sure some of this will come up. Clearly we disagree on climate, and I am sure that would be a discussion worth having.

Actually Christian Parenti’s most recent article was a review of Naomi Klein’s book about Naomi Wolf. You mentioned but didn’t discuss this with him. In this review, he affirms Klein’s view of Wolf, and seeks to separate his own criticism of what he calls the left’s mistakes in its pandemic response, based on, he contends, the left’s now widely admitted failure to do proper cost-benefit analysis of the health effects of lockdowns and economic recession, from Wolf’s conspiracy theories and climate denialism. I bring it up because you claim we, the left, are unwilling to debate you, on covid, on white supremacy, on climate. I want to assure you this is not so. If Christian Parent wouldn’t debate you, for whatever reason, you should know there are many people who will. We love debate, and we engage in it daily, with friends as with enemies. Can you say the same?

I’ll just add, I know that it’s terribly tempting when a bunch of upper caste bourgeois intellectuals get together, to spend all your time commiserating about the harms you suffer from affirmative action and diversity, but you have to admit it is petty to do so while the disparity of life chances is growing between your caste and the rest of us, with catastrophic loss of living standard for the diaspora of descendants of slaves, most acutely in the US. We could ask, are you really as victimized and marginalized as you say? As silenced and robbed? Do Naval Admirals in miniskirts really make it harder for you better, smarter, stronger, certainly far richer, real men, to advance toward your aims of social and political reform? When tenured professors Christian Parenti and Naomi Klein have got together, they have talked informatively about drought in Syria, the surveillance state in China, and malfeasance on Wall Street. With you, it’s mutual affirmation about how natural and understandable it is for (‘real’) ‘American workers’ to resent ‘spics,’ and mocking our demands for dignity. How comradely is this of you? Unlike his father, Christian Parenti does not claim to belong to the left. He calls himself a ‘classical liberal’ as Noam Chomsky has always done, and avows his centrist bourgeois political point of view in his book about Alexander Hamilton. But if you still consider yourself on the Left, you may want to consider where you’re going with all this vulgarian divisiveness.

Just a note. I grew up on welfare. I later made some money in Hollywood. But I never attended University. I mostly spent my youth in a losing dynamic with the criminal justice system. Your assumptions speak to your own resentments, Im afraid. The rest of your remarks are the usual boilerplate complaints I read a lot of places. You should just take up your beef with Parenti, WITH parenti. Also again, your remarks are simply strawmen. Nobody said any of that. ALSO.. I see you belong to the communist party of canada. At least your email address suggests that. Looking at the CPC, I notice support for electric cars. And how about just free public transport anywhere? And no corporations, rather than policing corporations. And what is *green technology*? And do you really believe carbon emissions are the story about global warming? Assuming there is global warming. Assuming its not a natural cycle or the sun or whatever. The people inventing this crisis are the same ones invented the covid crisis. I don’t pretend to know, but I certainly exhibit a healthier skepticism than the CPC. Pollution IS a huge crisis, and Capitalism is essentially the obstacle to finding solutions, but that is hardly a secret. But i risk extending this dialogue and i wont do that if you keep claiming we said, any of us, things we did not say.

I should add, I simply do not believe james hansen and his cohorts. Id suggest reading Cory Morningstar’s blog for the history, funding, and evolution of the green industry. https://www.wrongkindofgreen.org/blog/

I never said that. None of it. So what are you ranting about. NOTHING you just wrote has anything to do with me. See, now you just get blocked- So now you just get erased and blocked. I told you, if you kept lying and making things up, you are blocked. Interestingly you answered not a single question addressed you. Do not return. Thanks.

Sorry to hear about your heart episode. Glad to hear you were able to get quick assistance.

Yes, some technology in the 21st is incredibly useful. Despite my qualms about allopathic medicine, when my brother attempted suicide in 2020, several blood transfusions and dialysis brought him back to life.

That doesn’t mean we can’t criticize the weaponization of modern technology against people.

I still look forward to your essays, and hoping that you will be writing for many more years.

thanks, I appreciate that.