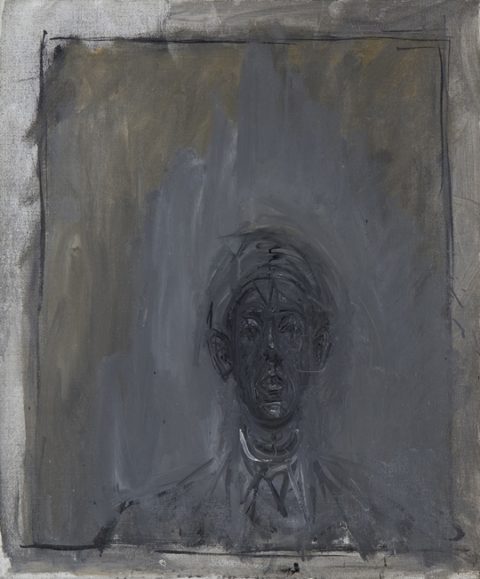

Alberto Giacometti

“In every one of the great scenes of Genesis and Exodus there exists a theme or a quasi-theme of the founding murder of expulsion. Obviously, this is most striking in the expulsion from the Garden of Eden; there, God takes the violence upon himself and founds humanity by driving Adam and Eve far away from him.”

Rene Girard (Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World)

“The table may have disappeared, but the séance continues regardless.”

Malcolm Bull (The Concept of the Social Scepticism: Idleness and Utopia)

“Among students of culture, the body is an immensely fashionable topic, but it is usually the erotic body, not the famished one.”

Terry Eagleton (After Theory)

“There can be no doubt, that collectives like those never can look for any kind of “healing” because capitalism produces illness in everybody, and because “psychiatric healing” only means re-integration of sick people into our society, but that instead of this all those collectives have to struggle to the aim to bring illness to its whole evolution , that means to bring it up to that point where disease becomes a revolutionary power by means of becoming jointly aware by consciousness.”

Jean Paul Sartre (Introduction to the SPK’s Turn Illness into a Weapon, 1972)

“The stock exchange is a poor substitute for the Holy Grail”.

Joseph A. Schumpeter (Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, 1942)

“…skepticism with respect to the other is not skepticism but is tragedy.”

Stanley Cavell (Disowning Knowledge)

I was recently going back to read Malcolm Bull. Terry Eagleton had a review in the LRB of his most recent book. It is interesting how Cambridge grads are good on Shakespeare. You can always separate Oxford alum from Cambridge because the latter are so steeped in Shakespeare. Anyway, it got me thinking about the direction of society as a very general topic. And I have to say that over the last ten years, roughly, I find most socialists and communists pretty much intolerable. I consider myself a communist, or at least something like that. But the truth is that the counter revolution, the one that eventually broke apart the USSR, also destroyed the communist diaspora, as it were. Old socialists (not all mind you) tend toward sclerotic and rote thinking. There is a quality of projection, almost, that makes friendship very hard. The new left is even worse though, because they aren’t even left, they are that strange new category of default capitalist who apologizes this away with demands for an end to crony capitalism or some such nonsense. You cannot be a ‘woke’ communist. Wokeism is not radical. All capitalism is crony– by definition, for the record. And the biggest single problem in this is that this new ersatz left has never read Marx. They have also only read the briefest of excerpts of Gramsci or the likes of Raymond Williams or Eric Hobsbawm, and even briefer fragments from Debord or anyone after him. They cannot really be called anti-capitalists. There are almost never anti-Imperialists. There is a disproportionate number of younger white males that fit into this category. They are also, usually, very angry.

Bull quotes the SPK (Socialists Patient’s Collective, Heidelberg, 1972)…..“The individual in his rationality is determined by the rationality of capital which he encounters as a force of nature, which he experiences daily and which therefore must appear to him as rational through and through. His protest against this life-destroying force can therefore only be a protest of feeling or emotion. But since ‘reason’ rules, these emotional outbursts of the individual are rationalised and ‘disappear’ into stomach pains, gall stones, circulatory problems, kidney stones, cramps of all kinds, into impotence, head colds, toothaches, skin diseases, back aches, migraines, asthma, car and workplace accidents, depression, and so forth – or feelings mushroom in interpersonal relationships (emotional plague), in flat affects (‘serious’ people), in psychosis etc.”

Gerhard Richter (Portrait of Mao)

This is very important today. Bull reviews a book by William Davies, and notes;

“Set up a social media account to share a few of your trivial thoughts with the world and you don’t expect to find yourself trolled towards suicide, but that can happen. And not just as a result of rogue operators: by using emotional analytics, surveillance capitalism – through platforms such as Facebook – can ruthlessly exploit your every weakness. “

Malcolm Bull (LRB, 2019)

One of the themes that runs through a lot of contemporary thought, besides ‘identity’, is what is meant by the term ‘social’. One thing seems clear, and that is that the social is under duress, and feels or is experienced in ways that make our sense of it feel precarious. A crisis of the social. The paring down of the self sees its double in the paring down of the social. The lockdowns now loom as the perfect allegorical event for the final eradication of the social. Contemporary society is now viewed (by the ruling class anyway) as extinct. The social is both obsolete and missing. The screen world has attempted to replace traditional society but it has failed, largely, and left a stunted half alive societal deformity in its place.

The traditional motifs of narrative have seemed to dissipate, somehow. But there remains the memory of the social. Everyone knows, are aware, that they live in a society. People talk and argue about society. And yet there is a haunting feeling of the insubstantial. The contemporary bourgeoisie, and likely everyone living and becoming ill, in the West, is haunted by the insubstantial feeling of their social life. Not a sense of receding friendships, though that often, too, but more of the gestalt experience of being ‘in’ society, a part of society.

“For most adults, the hidden is usually no more than a hypothetical condition marginalised by rationality. But for anyone who feels that there are things that they have not fully grasped, that there is something held back, that everything is not necessarily as it appears to be, this will never be enough.”

Malcolm Bull (Seeing Things Hidden, Apocalypse, Vision, and Totality)

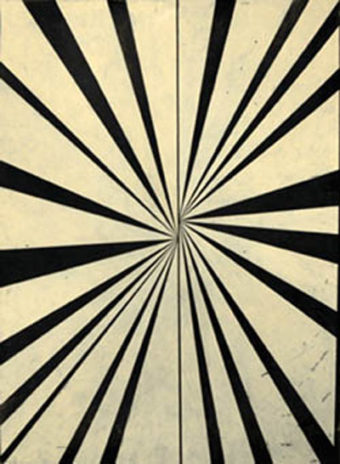

Robert Morris (1965, reconstructed 1972).

So, one of the lesser (maybe) qualities of the digital age is a sense that there is a waning of vividness, a gradual receding of experiential intensity. Now, is ‘hiddeness’ a trigger, as it were, for this? No, not exactly, but I think Bull is onto something in what he is saying. Bull in the quote below is discussing Zygmunt Bauman’s ideas on ambivalence….

“Thus, for Bauman, the “archetypal” undecidable is the stranger because he “is neither friend nor enemy; and because he may be both”. The inability to specify the ontic rather than the epistemological character of the undecidable means that it is defined only negatively. So, according to Bauman, the stranger is, like other undecidables, just the unintended consequence of the modern zeal for classification: “the refuse left after the world has been cleanly cut into a slice called ‘us’ and another labelled ‘them”‘.The net result is that

the distinguishing feature of contemporary society is simply that it has no definable character. Modernity’s ”bitter and relentless war against ambivalence” inevitably produces as its waste product still more ambivalence so that the “total of ambivalence on both the personal and societal plane seems to grow unstoppably”, until, in postmodernity, it acquires “the status if a universal human condition”.

Malcolm Bull (Ibid)

The short form here is that western post Enlightenment society has no ‘use’ for ambivalence, and that the appeal, or allure, of that which is beyond scientific category, beyond exchange value, really, is the result of something else in the trajectory of western culture. It is part of the end game for post modernity. And it is interesting to note the hostility today toward Marx, and even more toward Freud. And the disappearance of both the idea of and term ‘bourgeoisie’. Also, the figure of the ‘stranger’ (and I have written of this before, I know) remains one of enormous potency.

“But in the meantime, in the course of the nineteenth century, the syncretic figure of the ‘propertied and educated bourgeoisie’ had emerged across western Europe, providing a centre of gravity for the class as a whole, and strengthening its features as a possible new ruling class”

Franco Moretti (The Bourgeoise)

Mark Grotjahn

Moretti very insightfully tracks the European bourgeoisie protecting its class interests after the collapse of the ‘belle epoque’, and finding reassurance in fascism. And then after WW2, with the arrival, after much struggle, of new ‘democratic’ societies, globally, a sense of migration from standing behind brown shirts to a new self effacing discourse that allowed them to identify as middle class. And finally, the rise of commodity capitalism and legitimation through ownership of style and status. Consensus born of things and not men, let alone principle. In some sense this marked the end of the bourgeois class.

At least officially speaking. In the US, the configuration was always different because of the lack of a historical aristocracy. But to examine this shrinking experience of the social (and I have written before about the loss of experience, per se, though usually in a context of art) I think it’s important to look at the evolution of language as it relates to how society is described and the role this plays in character formation, and in how the idea of society itself has changed.

“In the last decades of the eighteenth century., and in the first half of the nineteenth century, a number of words, which are now of capital importance, came for the first time into common English use, or, where they had already been generally used in the language, acquired new and important meanings. There is in fact a general pattern of change in these words, and this can be used as a special kind of map by which it is possible to look again at those wider changes in life and thought to which the changes in language evidently refer. Five words are the key points from which this map can be drawn. They are industry, democracy, class, art and culture.”

Raymond Williams (Culture and Society)

Balthus (St Andre, 1954)

Williams continues ..: “Adam Smith, in The Wealth of Nations is one of the first writers to use the word in this way, and from his time the development of this use is assured. Industry, with a capital letter, is thought of as a thing in itself an institution, a body of activities rather than simply a human attribute.”

This is the fable of capitalism, in a sense. From assiduous work, the opposite of ‘idleness’, and diligence to an institution, a new kind of society. And the use of the term Industrial Revolution ties industry to revolution — meaning the French Revolution a mere forty years or so before. The word democracy changed, though not as significantly. Class morphed in a word that, in a way, replaced rank. But the more intriguing changes can be seen in the last two words, art and culture. Art changed (much as industry) from a skill, a talent, even, to a collective body of activities, an institution.

“Further, and most significantly, Art came to stand for a special kind of truth, ‘imaginative truth*, and artist for a special kind of person, as the words artistic and artistical, to describe human beings, new in the 1840, show. A new name, aesthetics, was found to describe the judgement of art, and this, in its turn, produced a name for a special kind of person aesthete. The arts literature, music, painting, sculpture, theatre were grouped together, in this new phrase, as having something essentially in common which distinguished them from other human skills. The same separation as had grown up between artist and artisan grew up between artist and craftsman. Genius, from meaning ‘a characteristic disposition’, came to mean ‘exalted ability’, and a distinction was made between it and talent.”

Raymond Williams (Ibid)

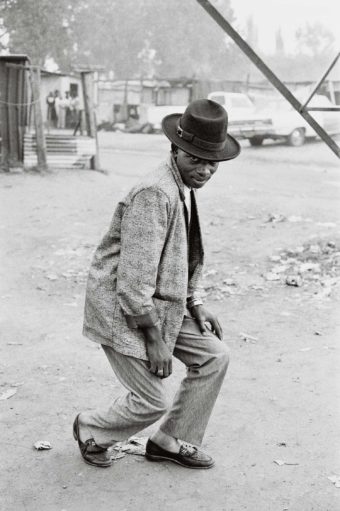

Santu Mofokeng, photography (Soweto, 1985)

Raymond Williams (Ibid)

The question today is what has become of culture, or of the bourgeoisie for that matter. What has become of the social?

“Only in the eighteenth century, in ‘civil society’, do the various forms of social connectedness confront the individual as a mere means towards his private purposes, as external necessity. But the epoch which produces this standpoint, that of the isolated individual, is also precisely that of the hitherto most developed social (from this standpoint, general) relations. The human being is in the most literal sense a zōon politikon [political animal], not merely a gregarious animal, but an animal which can individuate itself only in the midst of society.”

Karl Marx (intro to the Grundrisse)

This leads to a discussion of alienation. Perhaps this current ennui is the final evolution of Marxist alienation. But it’s actually even more than that, I think. For Marx the emancipation of humankind was the humanising of the world. That the eye could ‘see’ nature as a part of the social. But the institutions of society have become ever more remote from the daily life of their citizens.

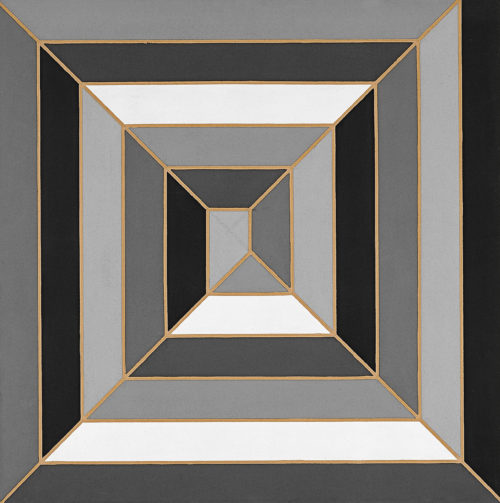

Zarina Hashmi

“Almost all the agencies through which political change was effected in the twentieth century have either disappeared or been seriously weakened.”

Malcolm Bull (The Concept of the Social Scepticism: Idleness and Utopia)

Eagleton makes a pretty astute observation regards post-modernism, and the fact that most post modernist theory is allergic to nationalism of any sort. That they arrived after the great liberation struggles of of the mid century (and before) and that interestingly the idea of ‘post colonial’ is a kind of comforting notion as its place squarely in the rear view mirror.

“Indeed the very term ‘post-colonialism’ means a concern with ‘Third World’ societies which have already lived through their anti-colonial struggles, and which are thus unlikely to prove an embarrassment to those Western theorists who are fond of the underdog but distinctly more sceptical about such concepts as political revolution.”

Terry Eagleton (The Idea of Culture)

Today the idea of governance has become ever more blurry. And educationally, civics is hardly taught even at junior high school, or high school level. (A 2016 survey by the Annenberg Public Policy Center found that only 26 percent of Americans can name all three branches of government). Less than half the population bothers to vote. Most states require no civics knowledge to get a high school diploma. And it is hard to argue about this because the cynicism is pretty justified. The level of corruption at the federal level of government is obvious, ongoing, and largely accepted by people. In one sense the disconnect from civic government mirrors the disconnect from culture overall, and the disconnect from others (since the pandemic this is obviously acute). But it also, more significantly, mirrors the disconnect internally, the disconnect that has led to this shrinking sense of experience.

Ute Mahler, photography. ( photo for the fashion magazine “Sibylle”, Minsk, 1981, USSR)

“Cicero’s dialogue, The Republic, Scipio defines a commonwealth as ‘the property of a people’ [res publica res populi]. But, he continues, ‘a people is not any collection of human beings, but an assemblage of people in large numbers [coetus multitudinis] associated in an agreement with respect to justice and a partnership for the common good’. This definition was picked up by Augustine in book 19 of the City of God: ‘A people he defined as a numerous gathering united in fellowship by a common sense of right and a community of interest.”

Malcolm Bull (Ibid)

What seems to be at issue, in late 20th century philosophy, is the role of vision. Or rather, ocular metaphors. Now, Bull has a long chapter on these debates in his Seeing Things Hidden: Apocalypse, Vision and Totality, those between Rorty, and Davidson, but also Martin Jay and his book Downcast Eyes. I actually think Jay is wrong in his idea of decreased visuality, but I understand the argument, and it’s one that takes in Wittgenstein as well. The point is complex, but the idea of ‘totality’ looms above all of it. And Heidegger is conjured by Bull (and others, too) and yet what becomes clear with Heidegger, always, is his return to a kind of mysticism. And I want to avoid tracking the entirety of this debate and instead focus on a few things I find pertinent.

“Man is not opposite the world which he tries to understand and upon which he acts, but within this world which he is a part of, and there is no radical break between the meaning he is trying to find or introduce into the universe and that which he is trying to fmd or introduce into his own existence.”

Lucien Goldmann (Lukacs and Heidegger)

This, if we followed one track, would lead back to quantum science. And to A.I. and all the discussions around the so called ‘hard problem’ of consciousness. But on another track it brings one to what I think Bull is trying to examine. And that is the entire blue print for the entire subject/object paradigm. This becomes a debate about holism, really. The conclusion, reached by different paths, between Rorty, Lukacs, Wittgenstein and Heidegger, too, is that there is a part of the world (sic) hidden from that which we normally understand. Or as Davidson put it, ‘truths’ that are hidden from that which we normally understand. And this is more what interests me here.

S.H. Raza

I have written before about the vastness of the earth. I was mostly speaking literally. Geologically vast. But on an epistemological level there is a sense of the incommensurability of the ‘world’ that always haunts us. And one of the problems with instrumental thinking is that it has incrementally ground down the ambivalent and uncanny in language and, because of its dominance, it has ground down our ability to experience hidden truths. Truths found, one can surmise, in this incommensurability. How can we know what we don’t know?

The problem is complicated by this idea of visuality. Bull asks what of these ‘holisms’ that are post visuality…which assumes society or culture IS post visual.

“If hiddenness is a relationship between vision and totality in which the whole is less than completely visible, then for the philosophers whose holism rules out the possibility of seeing the totality from a position outside of it, and thus the possibility of seeing the totality as a whole, the world as a whole is always effectively hidden.”

Malcolm Bull (Ibid)

But there is a problem with this. Vision, or visuality, while it has shaped language over the last two hundred years, is being spoken of in a register different than philosophical totality. We may have sentences such as “I see this or that…..”, which suggests an existential dimension, say, but also mean literally ‘seen’. This because of the primacy of vision in how we communicate. In our language. “I see” means I understand, but that understanding, what I take to be understood, is also literally ‘I see’. It might mean I see in my minds eye, as it were. And were are spiraling down into a metaphorical morass.

Alonso Cano (Christ Appears to St Teresa.) 1629.

Malcolm Bull (Ibid)

And this brings us back, directly, to the experience of the social. Our existential sense of ‘the social’. For clearly the social is ever more opaque in its formal presentation. Stanley Cavell has observed that if we cannot know for certain other minds exist, if the world exists, then its presentation to us is not a matter of ‘knowing’. Now I am going to detour (digress?) just slightly here because Cavell’s book of essays on Shakespeare is hugely relevant to this discussion. First though, I wanted to briefly note that reification, the imposition of exchange value on society (or capitalist society anyway) is the product of class struggle. It is inequality born of ownership of property etc. How much does that capitalist structure reappear in human psychology? Well, rather a lot. And how does this capitalist structure impose itself on the phenomenology of existence? Cavell sees the Shakespearean skepticism as the expression of tragedy. How does Capitalism influence how we read Shakespeare? How can the influences of class hierarchies find both literal and metaphorical expression in the human psyche? I would hazard a guess that over half the blog postings on this site address that question. Ours is a capitalist Shakespeare, a neo-liberal Shakespeare in fact, and increasingly a Shakespeare that takes on the sheen of fascist resistance.

“The glimpse is of an internal connection between skepticism and romanticism, of a sense of why skepticism is what romantic writers are locked in struggle against, writers from Coleridge and Wordsworth to Emerson and Thoreau and Poe (and for future reference I single out E. T. A. Hoffmann); and specifically in struggle for some ground of animism, which may take the form of animation (as emblematized in Hoffmann’s automatons, in Coleridge’s figure of life-in-death in The Ancient Mariner, perhaps in Frankenstein), a struggle as if to bring the world back to life from the death dealt it in philosophy, anyway in philosophical skepticism.”

Stanley Cavell (Disowning Knowledge: In Seven Plays of Shakespeare)

Frank Stella (1956)

This long trajectory of Enlightenment born rationality — the rise of science and scientific logic, is also the rise of an idea of progress. A progress pregnant with assumptions of Christian and Puritan/Protestant goals and reward, but it was also about a kind of identity, a self, an autonomous self. And there are splintering events over the last centuries, but the rise of fascism in the 20th century certainly presents itself as singularly disruptive. But this is a disruption that was the logical culmination of a number of forces. As capital accumulated in fewer and fewer richer and richer men, there came a demand to protect that capital from undeserving masses. The fear of communism drove a stark escalation in the repressive strategies of the ruling class.

The socialist patients collective I quote at the top was a kind of radical grassroots resistance that is close to extinct today. There are groups, but they tend toward very local problems. And there are obvious issues of consolidated authority and a global police apparatus in play here, there are also other reasons for this extinction. And it is likely that one such reason is the loss of experience. The loss of a capacity for desire.

The erosion of desire: this is a loaded question. But it brings us back again to the social. And also to interpretation. If one takes aesthetics — which I always do — it might be worth looking for the changes in representations of society in film and literature. The films of Val Lewton serve as a useful example of society post WW2. Lewton never directed (he produced) but he was the real auteur of his low budget RKO oeuvre and his work was directly linked to Romanticism (German and English). And to Shakespeare. I was thinking, too, of Anthony Mann’s westerns (westerns in general from the 50s). And here too the proportions were Shakespearean. Mann’s The Man from Laramie (1955) or the slightly later Man of the West (1958) are versions of several Jacobin revenge plays, and Coriolanus (in the case of Man of the West). Aldrich’s Vera Cruz probably should be noted, and of course Ford’s The Searchers. The forties saw the golden age of Noir, and the 50s went color, outdoors, and in the sun. The intimacy of noir violence became the more distant gunfighter shoot out in the street. And some of it was those actors, Stewart in particular. Clint Eastwood once said nobody lost his shit quite like Jimmy Stewart. Mitchum and Bogart were the noir icons, Stewart and Wayne the western . But the point of this digression is that the social was never quite as clear as it was in the westerns of Mann (in particular, and even more than in Ford).

Stewarts rage in The Man from Laramie is outsize. It is emotional grandeur. In a sense the paranoia of those 40s post war crime films became something set against the landscape of the West. And I have written before of the sensibility that looked westward. Clifford Styll and Agnus Martin. The Lewton films were almost the coda to noir. I Walked with a Zombie was essentially Wuthering Heights set on an island in the Caribbean. And it is tragic, and one wonders if any of the above were even remotely possible today. The answer is no. Not remotely. Ryan Gosling in Man of the West.

Tobias Verhaecht (Flemish, early 1600s)

This then is also connected class in American film. Mann, interestingly, was born ( Emil Anton Bundsmann) in San Diego, to immigrant parents from Bavaria. The parents got involved in theosophy (Lomaland, which I have written about (https://john-steppling.com/2021/12/christmas-2021-heres-what-we-know/) and when Mann’s father, a teacher, took ill he returned (with his wife, Mann’s mother) to Bavaria. They left Mann in the care of Lomaland. He was three years old. They didn’t return until he was thirteen. And then only his mother, for his father was permanently institutionalized. Mother and son moved to Newark NJ. They struggled and Mann went to work doing odd jobs by the time was fifteen. The point here is that he was a lower working class son of immigrants. He never went to college. In fact he never graduated high school. Film critic Robin Wood noted pain ‘matters’ in Mann’s films. There is no other director, I don’t think, that so insists on the suffering, the physical suffering, of his characters. There was, in Mann, an almost longing for tragedy. The Abstract Expressionist group had very similar biographies. The hard blue collar background, often the children of immigrants, strangers in a foreign land, and a sense of sincere deep emotion. Look at the ways the city was depicted in late 40s Noir, in the films of Fritz Lang, Robert Siodmak, or Otto Preminger. Or in the writings of Chandler or Cornell Woolrich. Or in Hammett and Hemingway. The social was embedded in the landscape. Even the most interior self involved interior monologue only existed within the social landscape, within a society that had clear outlines. A social history.

This segues back to the contemporary bourgeois subject. And to this curious idea of hiddenness. And linked here, too at the risk of utter incoherence, is the scapegoat. And, as Bull notes, the master/slave dialectic. The hiddenness that Bull refers to is (in one sense) that part of the world (society, culture, science) that is psychologically unable to be present. There is an interesting paragraph from Du Bois….

“After the Egyptian and the Indian, the Greek and Roman, the Teuton and Mongolian, the Negro is a sort of seventh son, born with a veil, and gifted with second sight in this American world, – a world which yields him no true self consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world. It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at oneself through the eyes of others…One ever feels this twoness, – an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body.”

W.E.B. DuBois (The Souls of Black Folk)

The Man from Laramie (Dr. Anthony Mann, 1955)

If one goes back to read Rousseau, or Adam Smith, or Hayak (god forbid), there is a subtle evolution of metaphor and meaning — in terms of how ‘society’ is imagined. And this evolution accelerated after Smith. If you go back to Hobbes and Spinoza, there are interesting contradictions but nothing (to my mind anyway) that suggests this creeping quality that degrades the human. Humanity as insects, essentially. The dignity of the human is gradually being erased and replaced with images redolent of workers in a hive. Ever since Smith’s ‘invisible hand’ there can be seen a reactionary element growing within the discourse. The society or the state (as Bull puts it), the social or the political. Marx, Engels, and Gramsci (and Lenin) imagined the withering away of the state. How that happened may have differed, but it a dream of emancipation. The insect came from Schmitt.

“The transition from state to society could not be expressed in the gentle imagery of etiolation and reabsorption; it was part massacre, part cannibal feast. The state is the mythical Leviathan, torn apart by the horns of Behemoth. As the flesh of Leviathan was devoured by the Jews, who ‘eat the flesh of the slaughtered peoples and are sustained by it’, so ‘political parties slaughter the mighty Leviathan, and each cuts from its corpse a piece of flesh for itself’. The organizations of civil society are ‘used like knives … to cut up the Leviathan and divide his flesh amongst themselves.”

Malcolm Bull (The Concept of the Social Scepticism: Idleness and Utopia)

The Third Reich embodied much of the unconscious alignment with ruling class hubris.

“Glossing Engels, Rosa Luxemburg argued that: ‘society faces a dilemma, either an advance to socialism or a reversion to barbarism’; either ‘rebirth through social revolution’ or else ‘dissolution and decline into capitalist anarchy’. The antithesis may be misleading. On this analysis, the latter may constitute the only route to the former, for the disorder of civil society is not merely statistical. In descriptions of this environment, there is a remarkable rhetorical convergence. For Hegel, it is ‘a formless mass whose commotion and activity could therefore only be elementary, irrational, barbarous, and frightful’; for Sartre a ‘place of violence, darkness, and witchcraft’; Luxemburg imagines it as ‘shamed, dishonoured, wading in blood … a roaring beast … an orgy of anarchy”.

Malcolm Bull (Ibid)

Harald Hauswald, photography.

One other note. The insect came from Schmitt, but his legacy was found in Leo Strauss and the University of Chicago group. Among the legatees of this fascist-insect sensibility are Victoria Nuland, Paul Wolfowitz (perhaps most influentially) and the Kagan family, Irving and William Kristol, and Allan Bloom.

“Organizing his followers, Leo Strauss called them his “hoplites” (soldiers of Sparta). He trained them to disrupt the classes of some of his fellow teachers. Several of the members of this sect have held very high positions in the United States and Israel. The operation and ideology of this grouping were the subject of controversy after the attacks of September 11, 2001. An abundant literature has opposed the supporters and opponents of the philosopher. However, the facts are indisputable . Anti-Semitic authors have wrongly lumped together Straussians, Jewish communities in the Diaspora and the State of Israel. However, the ideology of Leo Strauss was never discussed in the Jewish world before 9/11. From a sociological point of view, it is a sectarian phenomenon, not at all representative of Jewish culture. However, in 2003, Benjamin Netanyahu’s “revisionist Zionists” made a pact with the US Straussians, in the presence of other Israeli leaders . This alliance was never made public.”

Theirry Meyssan (The EU Brought to its Knees by the Straussians, 2022)

One can see (sic) the various threads that were the children of the Third Reich: Strauss, the Neo Cons that appeared first under Reagan (Elliot Abrams, Richard Perle, et al) and the Zbigniew Brzezinski clan. All have been, for all intents and purposes, the shapers of U.S. foreign policy for fifty some years.

Moretti comments, in a footnote to his book, something not to be overlooked:

“As the adjective ‘industrious’ makes clear, hard work possesses in English an ethical halo that ‘clever’ work lacks; which explains why the legendary firm of Arthur Andersen Accounting still included ‘hard work’ in its ‘table of values’ in the 1990s— while the clever arm of the same firm (Anderson Counseling, which had been concocting all sorts of investment practices) replaced it with ‘respect for individuals’, which is neoliberal Newspeak for financial bonuses. Eventually, Counseling strong-armed Accounting into validating stock value manipulation, thus leading to the firm’s shameful downfall.”

Franco Moretti (Ibid)

Francis Barrett (1801, Faces of the Magus or Celestial Intelligencer)

One other sidebar here, that not sharing private emotions (or secrets) is equated with masculinity in popular culture (especially Hollywood product). The strong silent type is synonymous with male virtue. And in one sense this is the inheritance of Puritanism. But it is more than that, or rather it has been ratified by a Capitalist system that finds a perfect subject position in the distant silent male.

There are several threads here that coalesce to produce the expression of a new tragic. I have suggested, as have many others, that tragedy is no longer possible. And perhaps that is right in a sense. But I think the current ascension of a new authoritarianism, globally, coupled to digital and internet technologies, are creating a post tragic sensibility. The silent male hero is now the autistic screen habituated follower of rules. (One film I am quite fond of, that approaches the tragic, is The Killing of a Sacred Deer, directed by Yorgos Lanthimos from 2017). Now Lanthimos is re-telling a Euripidean tragedy (Iphigenia in Aulis ), but it is the curious blank emotional palette that lifts this film into some kind of fatalistic discourse on mass autism. It is in the inverse of Man From Laramie. (also compares to Pasolini’s Teorema, 1968). It shares the deadened psychological subject that can be traced from Pinter to Schrader’s The Card Counter (2021) (and in fact, compare the Barry Keoghan character from the Lanthimos to Ty Sheridan in the Schrader). {one could add Tequan Richmond’s character in the much neglected 2013 Blue Caprice}.

“But experience suggests that there’s more that we don’t know than we do.”

Malcolm Bull (The Concept of the Social Scepticism: Idleness and Utopia)

“The creation of a culture of work has been, arguably, the greatest symbolic achievement of the bourgeoisie as a class: the useful, the division of labour, ‘industry’, efficiency, the ‘calling’, the ‘seriousness’ of the next chapter— all these, and more, bear witness to the enormous significance acquired by what used to be merely a hard necessity or a brutal duty…”

Franco Moretti (Ibid)

The Killing of a Sacred Deer (d. Yorgos Lanthimos) 2017.

Taylorism, as I continue to emphasize, is the catechism of advanced capitalist society. Fordism, too. But this is an internal Taylorism. A psychological Taylorism.

Terry Eagleton wrote this in 2000:

“In the postmodern world, culture and social life are once again closely allied, but now in the shape of the aesthetics of the commodity, the spectacularization of politics, the consumerism of life-style, the centrality of the image, and the final integration of culture into commodity production in general. Aesthetics, which began life as a term for everyday perceptual experience and only later became specialized to art, had now come full circle and rejoined its mundane origin, just as two senses of culture – the arts and the common life – had now been conflated in style, fashion, advertising, media and the like.”

Terry Eagleton (The Idea of Culture)

A bit later Eagleton quotes Andrew Milner (from Culture and Materialism):

“…‘it is only in modern industrial democracies that “culture” and “society” become excluded from both politics and economics … modern society is understood as distinctively and unusually asocial, its economic and political life characteristically “normless” and “value-free”, in short, uncultured’.”

I think one conclusion that can be reached regards culture (and by extension might include society depending on how you choose to define it) is that advanced Capitalism has (either by the internal logic of the profit motive, or by ruling class design) destroyed traditional venues of cultural expression. From trade unions, to small retail stores, to urban neighborhoods that were generational. And this went hand in hand with privatization. The rise of corporations. The rise of all things impersonal. Eagleton defines culture as the relationship between elements in a way of life. This is rather broad and maybe just meaningless, but I get the point. And coupled to these various definitions of culture is the idea of perfectibility. And that in turn, again, tends to bring things back to identity and self. Culture is, really, where identity is found. And it leads to consciousness. And that in turn, and I am more convinced of this than ever, to our mortality.

Anthony van Dyck (Self Portrait, 1632)

“And while culture in its most virulent forms celebrates some pure essence of group identity, Culture in its more mandarin sense, by disdainfully disowning the political as such, can be criminally complicit with it. As Theodor Adorno remarked, the ideal of Culture as absolute integration finds its logical expression in genocide.”

Terry Eagleton (Ibid)

This all becomes linguistic at a certain point. But this notion of identity remains a touchstone of sorts for how the societies of the West write about themselves today. As the aftermath of the pandemic lockdowns continues to be felt, it seems of some importance. And as Mbembe said, people today have digital memories. And really, identity is more doubled than it has ever been.

But allow me to quote Eagleton once again…from 2000…..again…..

“…the prospect now looms for the coming millennium of a progressively bunkered, authoritarian capitalism, beleaguered in a decaying social landscape by increasingly desperate enemies from within and without, finally abandoning all pretence of consensual government for a brutally forthright defence of privilege.”

Terry Eagleton (Ibid)

This authoritarian capitalism is already here, of course. As winter approaches the prospect of severe shortages of heating materials and disruptions in food chains, means the peoples of Europe and North America are going to have to investigate identity in some new fashion. One survey (from Sweden) shows one in five people believe that those holding wrong ideas should be deprived of their rights. (https://www.gu.se/sites/default/files/2022-06/101-118%20Persson%20o%20Widmalm.pdf) This is one more example of the savage Super-Ego.

Anja Salonen

As the idea of society itself blurs and begins to evaporate, the identity clings more tenaciously to its screen double. Identity politics is misnamed, probably, because first one must have an identity. But this is also no accident. The contemporary cultural landscape suffers from the loss of cognitive skills, a disenchanted atmosphere and increasing precarity across all but the top class tier. The erasing of class, as an idea, has succeeded in easing the identification with authority. But in a way this identification is more purely abstract and ahistorical than earlier forms of fascism. It is cleansed of overt ideology.

There is also the loss of sub-cultures. It is hard to have a sub-culture without an actual normative culture. The marketing of a climate crisis serves (as did the Covid pandemic) as a replacement for an actual culture, if not for society itself. The aggression and anger expressed at those who question the master narratives of one or another crisis today speaks to the sense of panic felt in the question of identity. The metaphorical level of cultural expression is now denuded and stripped of any clarity. This is really what disenchantment is, by and large. The identification with the state, itself stripmined of traditional meaning, has left this emotional deficit. Again this is largely the white bourgeoisie of the West, but it’s felt other places as well. The bourgeois class has been subsumed by something vague, and ineffable. Those truths of what we do not know are not on the menu. But then the menu largely looks like a blank sheet of paper. In lieu of actual ideology there is simply government propaganda. And government is hugely influenced by the billionaire class, unprecedented in power and reach.

“On the contrary, it is the character of the present time that all authority is founded on what cannot be experienced.”

Giorgio Agamben (Infancy and History; the destruction of Experience, 1978)

Quantum theory is viewed outside any political reality. But is this true? It doesn’t matter how one answers because the real issue is the loss of experience, which has led to the culture without culture and the untethered identity.

“The distinction between logical truths and truths of sufficient reason (which Leibniz formulates thus: ‘When we expect the sun to rise tomorrow we are acting as empiricists because it has always been so until today. The astronomer alone can judge with sufficient reason’) subsequently sanctions this condemnation. Because, against repeated claims to the contrary, modern science has its origins in an unprecedented mistrust of experience as it was traditionally understood (Bacon defines it as a ‘forest’ and a ‘maze’ which has to be put in order). The view through Galileo’s telescope produced not certainty and faith in experience but Descartes’s doubt, and his famous hypothesis of a demon whose only occupation is to deceive our senses. The scientific verification of experience which is enacted in the experiment- permitting sensory impressions to be deduced with the exactitude of quantitative determinations and, therefore, the prediction of future impressions – responds to this loss of certainty by displacing experience as far as possible outside the individual: on to instruments and numbers.”

Giorgio Agamben (Ibid)

Chauncey Hare, photography.

Agamben wrote this in 1978. Debord wrote Society of the Spectacle in 1967. The very first lines of Agamben’s essay are “The question of experience can be approached nowadays only with an acknowledgement that it is no longer accessible to us. For just as modern man has been deprived of his biography, his experience has likewise been expropriated.” People today take smartphone photos of their pseudo experiences. Cultural meaning has lost all relevance. Or rather, the relevance must be searched for, excavated, and submitted to an exhaustive interpretation. Such interpretation lies outside the skill set of most people living in the western world.

The climate crisis, like Covid, is outside direct experience. Computer modelling, and abstract statistical analysis provide something that substitutes for evidence. The unseen world that opened up at the end of the 19th century (with the discovery of optical instruments, including the camera and microscope) and which led to psychoanalysis has been replaced with the impossible to see, the proof is code. Instead of psychoanalysis there is algorithm.

“The Aristotelian conception of homocentric celestial spheres as pure, divine, ‘intelligences’, immune from change and corruption and separate from the earthly sublunar world which is the site of change and corruption, rediscovers its original sense only if it is placed in the context of a culture which conceives of experience and knowledge as two autonomous spheres. Connecting the ‘heavens’ of a pure intelligence with the ‘earth’ of individual experience is the great discovery of astrology, making it not an antagonist, but a necessary condition of modern science. Only because astrology (like alchemy, with which it is allied) had conjoined heaven and earth, the divine and the human, in a single subject of fate (in the work of Creation) was science able to unify within a new ego both science and experience, which hitherto had designated two distinct subjects. It is only because Neoplatonic Hermetic mysticism had bridged the Aristotelian separation between nous and psyche and the Platonic difference between the one and the many, with an emanationist system in which a continuous hierarchy of intelligences, angels, demons and souls (think of the angel-intelligences of Avicenna and Dante) communicated in a ‘Great Chain’ which begins and ends with the One, was it possible to establish a single subject as the basis for ‘experimental science’.”

Giorgio Agamben (Ibid)

Imagination no longer has a positive association. As Eagleton notes, satellite communication does not bear up well against sacred scripture. The West is not well placed for cultural revival. It is though, no doubt, going to see how far the new dessicated subjectivity of the people can be pushed.

To donate to this blog, and to the Aesthetic Resistance podcasts, use the paypal button at the top of the page.

The crony MONETARY SYSTEM is the actual unbalance… “capitalism”, “communism”, “liberalism” and all the rest of ‘ism and ‘ies are just sub-sets of it.

We either go for CHANGING the main system or everything we do on the sub-sets are just to keep ourselves entertained.

Carta de Conducao

thanks for the content,nice blog i really appriciate your hard work keep it up. also visit for super fast

help links