Marco Breuer, photography.

“What developed in the South was a theology carefully tailored to meet the needs of a slave state. Biblical emphasis on social justice was rendered miraculously invisible. A book constructed around the central metaphor of slaves finding their freedom was reinterpreted. Messages which might have questioned the inherent superiority of the white race, constrained the authority of property owners, or inspired some interest in the poor or less fortunate could not be taught from a pulpit. ( ) Stripped of its compassion and integrity, little remained of the Christian message. What survived was a perverse emphasis on sexual purity as the sole expression of righteousness, along with a creepy obsession with the unquestionable sexual authority of white men.”

Chris Ladd

“Thus, in Oliver Cromwell’s time, many educated Englishmen believed that God would bring the order of things to an end in the 1650s; and they looked in the Book of Revelations for allusions to l7th-century England as uncritically as any Texan fundamentalist looks today for signs of an imminent rapture of the saved. The fact that the end of the world did not occur on schedule deeply shocked many of the Commonwealth worthies; but in the meanwhile they discussed policies and plans within delusory horizons of expectation. ( ) When Ronald Reagan dipped into Revelations in the 1984 Presidential, campaign and included among his expectations a coming Armageddon, therefore, listeners with an ear for history heard in his words some disturbing echoes of the 1650s.”

Stephen Toulmin

“A Scottish observer indeed commented in 1614 on the ‘bitter and distrustful’ attitude of English common people towards the gentry and nobility. These sentiments were reciprocated. Only members of the landed ruling class were allowed to carry weapons: ‘the meaner sort of people and servants’ were normally excluded from serving in the militia, by a quite deliberate policy.”

Christopher Hill (The World Turned Upside Down)

“Every brilliant doctor hides a murderer.”

W.H. Auden

Ralph Gibson, photography. 1971

“The very meter in which John Donne writes An Anatomy of the World (his drooping iambics) marks the poem as an Elegy for cosmic and social decline: these iambic pentameters reappear 50 years on, in John Milton’s Paradise Lost.”

Stephen Toulmin

This meter, and even imagery, was repeated by William Butler Yeats in his often quoted ‘center will not hold’ poem circa WW1, The Second Coming. Donne was expressing a sorrow about the decay of an interconnectedness between psychological and political issues, as well as cosmological ones. Donne saw Copernicus and Kepler as threats to the Natural Order. Donne’s conservatism aside, there is probably no writer of English save Shakespeare, that was so sensitive to the historical echoes and resonances of the English language. What mattered was the correct expression of things in written language. Now, from Augustine onward (400 A.D.) there was a fusing of Cosmology with the political and the individual with both. Or rather, the cosmological was the backdrop against which human beings played out their personal drama of salvation or damnation. The individual was foregrounded, but foregrounded in a Christian spotlight, as it were.

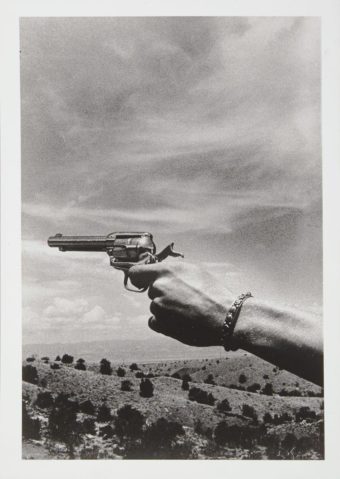

Martha Rosler, photography.

There has been a repeated retreat and advance of individualism since the Greeks, in one sense. In another sense the advances far outweigh the retreats. And there is also, per Raymond Williams, in The Country and the City, a change in how Nature (in a chapter on the idea of the *pastoral*) was being viewed and described over the last few hundred years. The view was artificial by the time of George Crabbe (early 1800s) — as Williams wrote it was the perspective of the ‘tourist or scientist rather than the working countryman’. This idea of perspective, then, is another investigative tool for examining how Western society in particular has evolved into its current state of hyper narcissism and how that in turn fuels the rise of global fascism today.

“It was slavery that first made possible the division of labour between agriculture and industry on a considerable scale, and along with this, the flower of the ancient world, Hellenism. Without slavery, no Greek state, no Greek art and science; without slavery, no Roman Empire. But without Hellenism and the Roman Empire as a basis, also no modern Europe.”

Engels

Ingmar Alge

Bourgeois art rose from the first stages of capitalism. And it came to reflect exchange value over use value. Except of course the seeds of this form of reason, what Adorno and Horkheimer called the “the court judgement of calculation”, were evident all the way back to the Greeks and Romans. Instrumental reason came to strip down Nature to only what could fit conceptually into a scheme that profited the subject. One of the qualities one feels when reading Donne or Milton, or Shakespeare, and certainly Dante (even in translation) is that the cosmological infuses the daily life of characters in ways that seem quite unusual today.

“The method of basing theories on “clear and distinct” concepts thus appealed to Descartes for two distinct kinds of reasons–instrumental, as solving problems in the empirical sciences, and intrinsic, as a source of “certainty” in a world where skepticism was unchecked.”

Stephen Toulmin

The Thirty Years War, I have said before, was hugely significant in shaping modern consciousness. There were already plebeian and anti-clerical traditions in England, and parts of Germany, in the Netherlands, too, and even in France; Anabaptists and Familists believed in itinerant preaching, in communal ownership of property, and that men and women might recapture Edenic innocence on earth as it existed before The Fall. The Lollards and John Wycliffe, who died in 1384, had an enormous influence. What is interesting is that the movement was made up mostly of uneducated agricultural workers, who besides rejecting confession and baptism, rejected the notion of a priest class. The radicalness of the Lollards is often sort of forgotten in a sense because it was subsumed in the English Reformation.

Otis Jones

“…teach that all are alike and that there is no difference betwixt masters and servant.”

William Gouge (Of Domesticall Duties, 1628)

“…the Cartesian program for philosophy swept the “reasonable” uncertainties and hesitations of 16th-century skeptics, in favor of new, mathematical kinds of “rational” certainty and proof ( ) -the devaluation of the oral, the particular, the local, the timely, and the concrete-appeared a small price to pay for a formally “rational” theory grounded on abstract, universal, timeless concepts. In aworld governed by these intellectual goals, rhetoric was of course subordinate to logic: the validity and truth of “rational” arguments is independent of wbo presents them, to whom, or in what context-such rhetorical questions can contribute nothing to the impartial establishment of human knowledge.”

Stephen Toulmin

This marked the end of a kind of preeminence in philosophy for argumentation and logic, but also for ethics. For the moral essence of Reason.

Alterpiece St. Martin’s Cathedral, Utrecht, defaced 1566.

With this shift came a receding of the background of Nature. No longer background, it became the far background. The relationship between this court of calculation, the eroding cosmological vision of interconnectivity, and language as a tool of expression, an expression that sought the inexpressible is highly complex but often treated free of class analysis, and more, with a strange indifference to aesthetics.

“One is well advised to look for scientist stress in any terminology that has its start in modern idealism. Thus, although the cult of imagination is usually urged today by those who champion poetry as a field opposed to science, our investigations would suggest the ironic possibility that they exemplify an aspect of precisely the thinking they reject.”

Kenneth Burke (A Grammar of Motives)

Mohammad Ehsai

Burke’s quote is very significant, I think. So I will take a moment more to look at that. The following paragraph is devoted to an essay on poetics by Wallace Stevens. I am never sure if Im yet old enough to fully appreciate Stevens. But what Burke takes away from Stevens (and more on that essay below) is that there is a tendency to see philosophy and reason as vocational — what you do during office hours. Something official. And poetry is vacational (Stevens) or unofficial, what you do after hours. This was not an endorsement by Stevens, but rather the opposite. Burke also notes Descartes, who is viewed as the father of this kind of scientism — Burke’s term — and who is credited with providing authority and legitimacy to this court of calculation. And of course, the obvious take away here is that all of us that write anything approaching critical analysis are in the shadow of scientism and of Descartes.

“It is a violence from within that protects us from a violence without It is the imagination pressing back against the pressure of reality. It seems, in the last analysis, to have something to do with our self-preservation; and that, no doubt, is why the expression of it, the sound of its words, helps us to live our lives.”

Wallace Stevens (The Necessary Angel)

Julie Blackmon, photography.

This shift became a critique now familiar via Frankfurt School thinkers, that instrumental reason was in the service of standardization and the narrowing of experience, and all toward a control of social relationships. Adorno believed art was only art if it was resistance to what Burke called scientism. A violence from within, as Stevens put it. The dilemma, aesthetically speaking, is that scientism became infused with everything, not just with language. And resistance to this extreme saturation of experience and discourse risked falling into pure irrationality, an irrational that was regressive and linked a cliched and almost kitsch mythology. And one sees today the effects in turns toward a new primitivism, which is only superficial and worse, is really only the afterbirth of bad calculation. Rainer Nagele described the total organization of experience by the bourgeois public sphere — one that prevents the articulation of new modes of experience, but also prevents new experience itself. The impulse or motivation to escape instrumental language can only find traction in (per Nagele) the gaps and ruptures that negatively appear in the text.

So what of those drooping iambics of John Donne? This is what is so unsettling when reading English from the 17th century and before. And this is something that Rainer Nagele notes in his essay on Celan and Freud and Kafka.

Wallace Stevens with daughter Holly, 1925

“Walter Benjamin’s essay on “The Task of the Translator” develops a different concept: the original is not any given, positive language; each such language is already a translation, a metaphorical space of displacements and approximations of an original which itself is not an existing language. Freud’s interpretations of dreams are translation in this other sense: translation of something that is already translation, because “it” is never where “it” speaks. The translation of the manifest dream into the latent dream thoughts is still a translation into a language shaped by secondary elaboration, not the language of the primary processes. And yet the being of the subject is affected by this language, which it effects through all the detours of displacement.” Rainer Nagele

Scientism assumes a kind of property relations model for subjectivity. Scientism is inextricably tied to Capitalism, then. Everything is translated and everything is displaced. One can no longer find writing that possesses the quality of sensitivity and nuance that one finds in Donne or Milton. Compare the Yeats poem to the Donne. What is the difference? It is hard to find a satisfactory answer, but there *is* a difference. And the answer, if there is one, may be the quality of rationality in Yeats. The missing cosmological, in a sense.

Peter Kayafas, photography.

It was Lacan who noted the ahistorical nature of ego psychology. And this observation is tied in with Freud’s ideas on belatedness . The relevance here is tied into latency and the re-ordering action of memory. A re-ordering that includes a latency period and a forgetting. Now, without going into Lacan’s theories about this, the point is that something must trigger this emergence of fragmentary memory. So the point, in short form, is only that we remember and re-order that memory because of a situation *now* that demands it, and demands it for future projection. Poetic language, that Stevens’s violence from within, is an action that resists this court of calculation, this scientism or false instrumental rationality, by way of finding the voice of that lost rupture. And Lacan was right to note that this is not the story of the individual — or rather it is the story of social memory as it happened to the narrative voice. The Donne poem expresses a sorrow that doesn’t scan in the court of calculation. Yeats poem, as good as it is, does. The Donne poem also addresses something more than just the reader. It is not exactly impersonal, but it is, to some degree, a declaration for the future.

“At the age of one and a half years, the child receives an impression to which he cannot sufficiently react; only at the age of four years he understands it, is grasped by it (von ihm ergriffen) through a reactivation of the impression [hei der Wiederbelebung des Eindrucks], and only two decades later he can grasp with conscious thought the events that took place in him”

Freud

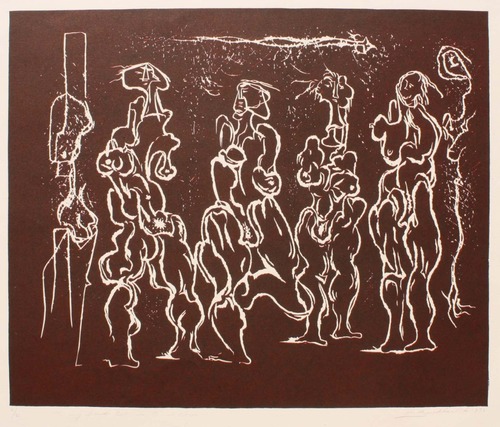

Hans Burkhardt

“The relations between the ego and reality must be left largely on the margin. Yet Narcissus did not expect, when he looked in the stream, to find in his hair a serpent coiled to strike, nor, when he looked in his own eyes there, to be met by a look of hate, nor, in general, to discover himself at the center of an inexplicable ugliness from which he would be bound to avert himself On the contrary, he sought out his image everywhere because it was the principle of his nature to do so…”

Wallace Stevens

Burke has a fascinating couple chapters on mysticism. And he observes that the ingredients for the mystical are built into the Kantian abstract. That behind the abstract (synthetic unity of apperception). That system — says Burke — allows us a glimpse of the anonymous stranger wandering through the poems of Shelley. And this is the heart of what I am trying to get at here, I think. And it is about identity, about the language of scientism and how art navigates the contradictions of how we speak about ourselves (often just to ourselves). The person we encounter at the far edges of language, says Burke, is a super-person, or transcendent self. For this is what lies behind the shift inaugurated by Descartes. This transcendent self is the product of a collective medium. And here one bumps back into Freud and Lacan, and perhaps, too, to the ways art and the uncanny always seem to interact.

For Burke, there is a mystery in the ways images are generated. What degree of purposiveness is legible, or to what degree it can be tracked, is often unclear. To speak of a ‘calling’ or ‘vocation’ is born of an image of a voice calling from inside, from our personal metaphoric space.

Francisco Ribalta

“All scapegoats are purposive, in aiming at self purification by the unburdening of one’s sins ritualistically, with the goat as charismatic, as the chosen vessel of iniquity, whereby one can have the experience of punishing in an alienated form the evil which one would otherwise be forced to recognize within.”

Kenneth Burke (A Grammar of Motives)

There are several branches of thought here; one has to do the ineffable, which Burke discusses. The second has to do with panpsychism . And the third has to do with with what Burke calls *word magic* but which is intimately linked to the uncanny and to belatedness. All three are relevant to what Donne was doing in his poem of 1611. And that in turn is tied into the arid experiential landscape of the contemporary West.

“Though we usually take such rites as perfect examples of word magic, I am trying to suggest that word magic is but the failure to carry through the original insight. By this notion, word magic has its origins, paradoxically, not in a naive belief in the power of words but in man’s first systematic distrust of words. It began with the ineffable.”

Kenneth Burke

Ewan Gibbs

“Another purely biological motive involved in mysticism derives from the fact that at the very centre of mobility is the purpose of the hunt. Hence the imagery of the desired as that for which we “hunger,” so that the quest for prey can become transformed into the erotic quest.”

Kenneth Burke

The biology of the purposive, for Burke, also ties in mystic silence with hunger, with stalking and the hunt. And here the cave drawings at Lascaux are worth considering. For the birth of alphabets and grammar were also about hunger and quests. The animals were not abstracted totems, they were language. When we speaking of a *higher* calling, it is the sight afforded the hunter scanning the horizon, and his discovery of prey which both has mystical silence resonances, and which *calls* to him within. The anticipation of quelling hunger is then both spiritual and erotic. For silence looms profoundly in so much theatrical tradition, from Noh drama to Pinter and Beckett, from Shakespeare to Handke. And in Pinter, that silence is the killing of anticipation, at least the anticipation of satiety.

Finally, though there is something about belatedness that intersects with Capitalism, with investment and return. With the delayed gratification of financial quests. But the economic hunt returns only abstraction, and hence it is the negative mystical. The internalized purposive for Capital is always a negation of desire. Hence the crudity of objectified sexual relations, the triumph of exchange value, and all the other aggressions of symbolic conquest. Wall street is faux battlefield and its soldiers are pretend warriors. The hunt is never silent. For capital demands noise.

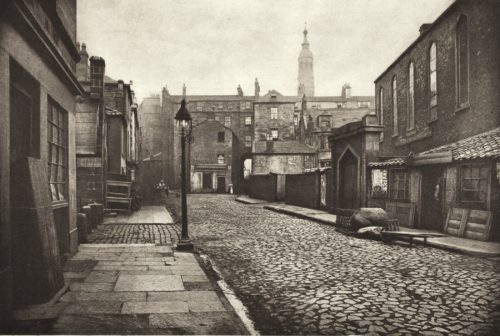

Thomas Annan, photography (Glasgow, 1870 apprx).

One of the things that capitalism does is to monetize everything, even thought processes. And there is a strange overlap with Christianity, then, to such a degree, in fact, that I suspect Christianity became something almost unrecognizable today if seen by the early Church followers. The monetizing of guilt, redemption, and salvation feel almost natural, today. And it does seem likely that all notions of accountancy are linked at their origins to Christian ideas of the eternal return and future reward. And these in turn are unavoidably tied to belatedness, again.

Freud believed that a traumatic encounter might well only be recognized AS traumatic, in a sense, because later conditions (puberty for example) provide a symbolic and functional context. So that a later encounter or event, which resembles the original trauma, can trigger a re-experiencing of the trauma anew. To experience it AS trauma this time. PTSD sufferers often have these latency periods and a kind of amnesia that masks the original event.

Lee Miller, photography (Buchenwald guard, beaten and hanged).

“Despite the fact that the subject cannot make sense of what is happening and becomes overwhelmed, the event leaves behind some sort of a “mnemic trace.” From within a Lacanian framework, this first episode is engraved in memory by the promotion of a single signifier or representation that comes to signal and cover up the original lack of understanding (Verhaeghe, 2008). This single signifier, which is metonymically chosen by the subject, hems in or borders the hole of the nonsensical experience…( ) Due to the failure to bestow meaning on the event, to understand it, to realize what has happened, the subject (as an effect of the concatenation of signifiers) is excluded from it. Ultimately, the event can be said not to be subjectively experienced at the time of its occurrence. It is a missed encounter, or an “unclaimed experience,” as Caruth (1996) calls it. Hence, the experience initially remains without long-term consequence. Nevertheless, the person who underwent the event is obviously deeply troubled by it, which is evidenced by the acute reaction of distress and fright and by the fact that the scene leaves a mnemic trace. The initial experience opens up an enigma; it raises a question. This question is pending and awaits an answer—sometimes for years. “

Gregory Bistoen & Stijn Vanheule

Freud seemed from the very start to be fascinated with ideas of amnesia, with an inability to remember traumatic events, and how this is talked about raises secondary questions about the spatial symbolism involved. But what does all this mean for childhood amnesia?

Joseph Cornell

“In the great majority of cases it is not possible to establish the point of origin by a simple

interrogation of the patient. This is in part because what is in question is often some experience that the patient dislikes discussing; but principally because he is genuinely unable to recollect it and often has no suspicion of the causal connection between the precipitating event and the pathological phenomenon.”

Freud and Breuer (Studies in Hysteria, 1895)

“High and low things are linked so that motion in nature, and action in society, flow from high to low creatures. The systems of Nature and Society also exemplify ed the role of hierarchy in 17th and 18th century thought. Passive and material bodies were lower in the natural hierarchy: active and vital ones were higher.”

Stephen Toulmin

So, belatedness (apres pre in French translations, and often ‘deferred action’ in English) might be seen in light of Burke’s notions of the purposive, in the grand hierarchies of European thinking after the Enlightenment, and how all of this language begs questions of origins. There were sub texts to the models of reality that held prominance in Europe from the 1600s onward, and many were class based and geographic. Sciences in England were discouraged by Royal socities (anthropology was alright because it was an offshoot of colonial administration) and psychology later flourished in Scotland as a reaction to English oppression. In the U.S. today the acceptance of privitization is acute, and such acceptance means that the mask of identification ( something even Burke noted) with sports teams for example, entails a suspension of understanding, in a sense. Billionaires own those clubs, and often move them when a better deal is offered. But people attach themselves, symbolically, to these teams anyway. The players are from all over, not local, but that doesn’t matter either. It is all a strange dumbshow of allegiance. A pantomime of loyalty. Why does such artificiality become not just acceptable but nearly hysterical?

A vanitas sculpture, 19th century. Anonymous.

“Without even going into Freud and Breuer’s theory of repression, strangulated affect, and split-off psychical groups, one thing is clear: what causes hysterics to suffer is a memory, a singularly paradoxical kind of memory: an unremembered and unforgettable memory.”

Elizabeth Rottenberg

A side note then on panpsychism. There seems to be some curious trend that wants to take this idea as serious. And its true that some forms of Jainism and Advaita Vedanta believe in a kind of universal consciousness. I only mention this because as a boy (a very sickly boy) I tended to imagine that everything in the world was conscious. That stones or swans or paper bags were conscious. I would kick a stone back over to the group of stones from which it had become detached because I felt it would be happier and less lonely there, back with its group. On some level this says more about me as a child than it does about the validity or lack thereof of panpsychism. But what IS relevant about the small uptick in interest in this topic is that it highlights the rather large distrust of philosophy in the contemporary world. Both Bertrand Russell and Arthur Eddington, back in the 1920s, gave some credence to the idea of panpsychism. But current debates on consciousness are beyond the scope of this posting. I only mean to point out that such topics are worth exploring. (I still kick stones back to their group by the way).

The real issue has do with how the obvious degrading of language effects the collective, and how a resurgence in fascist thinking and symbolism, as well as aesthetics overall, seems to be gaining influence. The crudity of so much mass culture, the inability in most people of the West today to read anything but the most simple narratives, suggests that the mechanisms of control operate openly now.

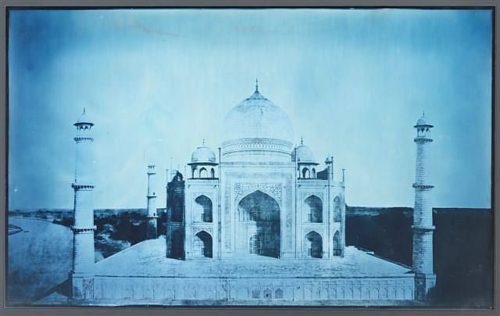

Adam Fuss, photography.

“The Christian dialectic of atonement is much more complex than this, hence includes many ingredients that take it beyond the paradigm we are here discussing. Here we are concerned rather with the kind of scapegoat seen in the Hitlerite cult of Anti-Semitism. Here the scapegoat is the “essence” of evil, the principle of the discord felt by those who are to be purified by the sacrifice. Note also that the goat, as the principle of evil,would be in effect a kind of “bad parent.” For the alienating of iniquities from the self to the scapegoat amounts to a rebirth of the self. In brief, it would promise a conversion to a new principle of motivation-and when such a transformation is conceived in terms of the familial or substantial, it amounts to a change of parentage.”

Kenneth Burke

Here the assigning of parental authority to Fate, in the form of a goat in this instance, segues nicely with the wholesale condition of belatedness in a society of mass social trauma. And, the shift to instrumental thought carried with it the rise of narcissistic personalities. In a society that does not feel the emphasis becomes about how “I” feel.

People are united by a shared hatred of a symbolic enemy or threat. And when that enemy cannot function as an enemy (as Burke notes, even grammatically) the frustration turns inward. One is no longer defined by what one is not — I am not the enemy — but that division becomes blurred or inoperative and hence there is an ascension again of the Death Drive. The need to restore some kind of equilibrium, at least internally. Perhaps this accounts for the self destructive nihilism of the ruling class today. Or the base churlish ignorance of the Evangelical Christian. Better nuclear annihilation than having to see the emptiness within. That I am not anything. My ownership still does not mean I exist. When the scapegoat mechanism is short circuited the transferring of guilt is interrupted. Burke quotes Otto Neurath, who wrote (Foundations of the Social Sciences) something perilously close to panpsychism…..“We suggest not starting with the antithesis: living being and the environment (as bio-ecology does), but starting with what may be called a “synusia” composed of men, animals, soil, atmosphere, etc. I am here using the term ‘synusla’ in analogy with the term ‘symbiosis,’ and I hope that the old theological use of the word will not mar our argument ….”. Additionally, in the scapegoat mechanism (per Raymund Schwager) the transfer of guilt is never complete. Hence violence returns. And hence there is a need for repetition.

The hidden grammar of classification haunts contemporary capitalism. Often, of course, it is not hidden. But as in the attempts toward new primitivism or new age practices, the result is the opposite of that intended. The touchy feely ethos of privileged liberals is always one of savage policing (think the issue of gun control, where the current protest will inevitably lead to worse violence). All groups that eschew class analysis in favor of identity definitions end up fixated on retribution. The mechanisms of punishment lurk in the very language of the post modern world, and function almost without exception free of critical awareness.

Ed Valfre, photography.

As always, one can donate in support of this blog. There is a PayPal link at the top of the page. Many thanks to those who have.

Not done reading yet John but great work as always so far. Commenting anyways because I feel the need to ask, where does one find this essay on Celan and Freud and Kafka by Nagele? Would love to read that. Keep up the great work!

https://www.amazon.com/Reading-After-Freud-Rainer-N%C3%A4gele/dp/0231062869/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1522274021&sr=1-1&keywords=reading+after+freud&dpID=31cuK1WQ4wL&preST=_SY291_BO1,204,203,200_QL40_&dpSrc=srch

i’m editing a journal i kept last year and parts of it remind me of your posting. Here’s a sampling of what I mean:

“I remember peering up from my bed through a veil of pain at the yoga ball I use as a chair, resting itself next to the bookshelf like a giant clown nose and watching me. Watching me just as all objects and things and parts of the earth and nature watch.”

I think the more interesting question is not whether panpsychism exists, but how accepting this metaphor/mindset might alter our relations to the world in an ultimately more ethical way. While I do identify strongly with the feeling that things around me have consciousness (I did as a kid and never lost that), I do not identify as a “panpsychist”, and am open to the possibility that individual objects are not conscious per se, but that I am tapping into a certain mode of perception. What this “mode of perception” is, how it operates, where it comes from, are up for debate. It could, for instance, have something to do with the mechanisms the brain uses to protect oneself from knowledge of certain early traumas, as mentioned above. Or, it could be a mechanism for dealing with pervasive boredom in a society which assumes we can know everything and have authority over ourselves, others, and the earth/environment.

Another thought….kids do this all the time with teddy bears, i think. They imbue the bear or comfort object with consciousness. When is this lost? And why? Is it irretrievably lost? Can we retrain ourselves to appreciate that mode of perception/knowing?

Anyway, I do feel that this way of describing objects as having consciousness or agency, tends to say something very true about how I sometimes experience the world, which the opposite assumption could not convey. And I think that when we are looking at trauma theories and about “claiming” that which cannot be claimed (Caruth, as cited above)–we must practice using alternate metaphors and narratives which shatter our usual way of perceiving things, in order to ‘reclaim’ that memory or truth that defied the logic of our way of narrating and understanding the world when the trauma first occurred.