Ian Fisher

“Crimes of which a people is ashamed constitute its real history. The same is true of man.”

Jean Genet

“I am haunted by no phantoms. It is rather that the ashes I stir up contain the crystallization that hold the image (reduced or synthetic) of the living and impure beings that they constituted before the intervention of the fire. If life has a meaning, this image (from the beyond?) has perhaps some significance. That is what I should like to know. And it is why I write.”

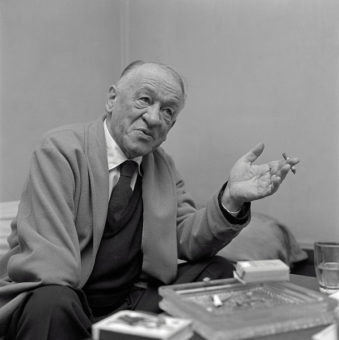

Blaise Cendrars

So, Bob Dylan wins the Nobel Prize for Literature. Now, first off, this prize is a bit like being named poet laureate of a country. Except it is even more irrelevant. At least in terms of art. But that’s a slippery definition at best, and before getting into some kind of analysis of that term its useful to look at the history of the prize. The Nobel committee is, for literature, made up of mostly academics of one sort of another. Nominations come in from a variety of sources and are sifted through in the manner of all committees. Which means this is always a compromise prize. James Joyce never got one, neither did Kafka or Tolstoy. In the early years of the prize, the model was the Academie Francaise. Strindberg famously ridiculed what he called the self appointed immortals of the committee. Of course Strindberg never won. The committee dismissed Thomas Hardy because his “god lacked any sense of mercy or justice”. The early years favored Victorian sensibilities and some vague sense of classicism, whatever that meant. Tolstoy was dismissed because of his fatalism and anarchist sympathies (per Burton Feldman) but in the end was chosen only to reject the offer and the committee found a substitute in the relatively obscure Theodor Mommsen. Later the Nobel committee decided it was time to embrace modernism but not before rejecting Ibsen and Zola for reasons very similar to Tolstoy’s. The list of mediocrities continued until 1920 when Knut Hamsun won, but then Hamsun was a fascist (but at least a significant writer). The modernist trend began, I guess, with William Butler Yeats — sort of. Although the noted *idealism* and classicism was still very important. And Yeats was conservative politically. The award also goes, almost always, to writers who are safely distanced in time from any political controversy. Hemingway didn’t get it until after 1948 (he won in 54) and the defeat of fascism and all that meant. The list from the 40s is a curious mixture of great (Faulkner) and sub mediocre (Johannes V. Jensen, a Dane who favored crypto eugenics racial theories). Some like Gabriela Mistral are simply mostly forgotten. But the rise of modernism created acute contradictions for the committee. Not just their relative political conservatism, but their confusion overall to arrive at any sort of coherent criteria for the prize.

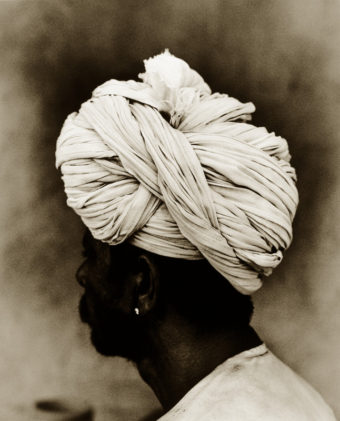

Stuart Redler, photography.

Churchill won in 1953, and the less said about that the better. Juan Ramon Jimenez won in 56, and that proved to be a prescient choice as Jimenez looms as more significant today than he did at the time of his winning. A number of Soviet writers won, and just as many anti Soviets. The cold war played out as a weird narrative of carrot and stick. By the 70s the choices were clearly influenced by previous choices and by appearance. Some were good, like Eugenio Montale and some bizarre like Eyvind Johnson (but then he was a Swede). Beckett won way back in 1969. But without going over all the winners, the point is that a Patrick White won and Joyce didn’t. Wole Soyinka was the first black African to win in 86. And the last. The prize has gone primarily to novelists, with poets second and playwrights far behind in third. This is worth pondering, I think. Poets of course don’t translate as well. But playwrights?

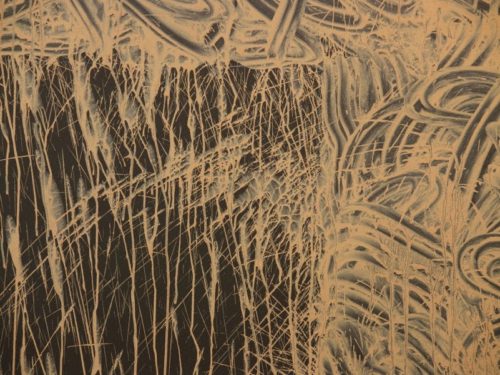

Florian Pumhosl

More on that later. Off the top of my head I can think of a number of writers I might have thought would be favored. Athol Fugard at the top of the list. But also James Kelman and Richard Ford. Cormac McCarthy maybe, William Gass and Jon Fosse. Ladbrokes had Dylan at 50 to 1 odds. Syrian poet Adonis was 6 to 1. But there is Rohinton Mistry and Joan Didion, and Thomas Pynchon — who I’d love to see win just because it was would be great strange theatre. Surprisingly Handke was only 25 to 1. I can think of no greater living writer, personally. Fugard is close, though, and Kelman. Ryszard Kapuściński died in 2007 or I’d have had him as a possible deserving winner. Roberto Bolano, too. But I, of course, have no idea what deserving means. Robert Bly is on my list. How did William Burroughs not win? Hell, how did Raymond Chandler or Dashiell Hammett not win? Churchill won but not Malcolm X.?

A week before the prize was announced Alex Shepard wrote…

“With the last three Nobel Prizes having gone to a Canadian international bestselling author who writes in the coveted “people looking at lakes” category (Alice Munro), a French guy who writes about remembering stuff that he thought he forgot but actually didn’t (Patrick Modiano), and a Belarusian woman who sort of makes stuff up and calls it oral history (Svetlana Alexievich), this year’s winner is anyone’s guess. “

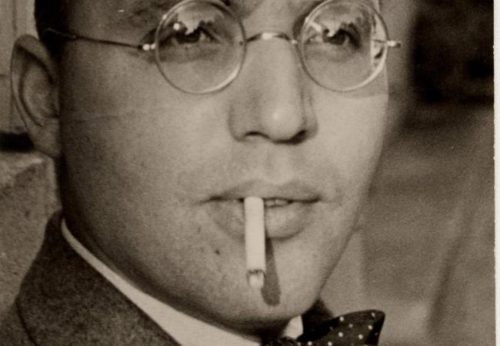

Kurt Weill

The looking at lakes category is also called the looking at lint on my sweater category. Speaking of which Virginia Woolf never won. Chekhov, Brecht and Ionesco never won, and neither did Tennessee Williams. Or Jean Genet. Playwrights. Though Genet wrote novels as great as any in the century. Galsworthy won instead of Joseph Conrad or Woolf or Sean O’Casey. For there is, even with the deserving choices, a sense of middle brow conformity running through all this. And that brings me back to Dylan, the first writer to win who has pimped for Victoria’s Secret and Chrysler (and Pepsi and etc). Bill Hicks once said if you do a commercial you are off the artist roll call forever. But I suspect Dylan marks the first post literate choice for literature. The first post text winner. Dylan actually wrote two books and both are dreadful. If you read his lyrics without music, they are also dreadful. But he is a popular synthesizer of various American musical forms. Though one would think Woody Guthrie or Leadbelly should have gotten the award then. But Dylan has always been a teflon sort of celebrity. When he embraced Christianity, of a sort, for a while, he got a pass. But that is the point, I think. This is the post post modern award for anti literature.

Jeff St. Clair commented (at Counterpunch):

“The announcement that Bob Dylan has won the Nobel Prize for Literature induced much carping from uptight academics about the alleged degeneration of the award. How dare they honor a rock singer? My question is what took them so long? The crusty Nobel committee should have recognized the role of popular music at least 35 years ago and given the prize to Bob Marley. Even Dylan would probably admit that Smokey Robinson should have been in line ahead of him.

Still Dylan deserves the recognition. He’s the greatest white blues singer and probably the best songwriter of the rock era.”

But see, if I bought this, and I don’t (though St Clair made another sharp point in that same article…more below) that’s still not a small issue. Marley I might feel better about, in fact. Marley so far as I know never did a Cadillac commercial. But beyond that I’m not an academic though I also don’t think one can denigrate such an absurd literary prize. If Pearl Buck and Churchill didn’t denigrate it, then its beyond denigration.

Alexandra Exter (1917).

If I had to pick three writers who have been the most overlooked in the last 100 years it would be Herman Broch, Patricia Highsmith and Blaise Cendrars. Honorable mention to Juan Rulfo. But the craft of writing, however one approaches it, is strategically transcendent — by which I mean that something deeply important and urgent lies within all textual art. And perhaps Broch is not exactly overlooked so much as just not read. Though again, nobody reads anymore it seems. Sebald might have been another choice but so far as I know never got close. Broch certainly didn’t. But music is another category. Weill and Brecht would be overwhelming choices if this award had been meant to include the very things the Nobel committee just wrote about Dylan.

“A philosophy of language, as Leibniz and Herder understood the term, will turn to the study of literature with especial intensity; but it will think of literature as inevitably implicated in the larger structures of semantic, formal, symbolic communication. It will think of philosophy, as Wittgenstein has taught it to do, as language in a condition of supreme scruple, the word refusing to take itself for granted. It will look to anthropology for sustaining or correcting evidence of other literacies and structures of significance (how else are we to “step back” from the illusory obviousness of our own particular focus?). ”

George Steiner

Blaise Cendrars

But there is more than just the complexities of transcendence, the formal and allegorical; there is the loss of seriousness. The erosion of that sensibility of the serious is one of the primary casualties of the post textual age. The digital era has brought with it a superficiality and loss of historical reflection. And while that may sound like *carping*, its not. Advanced capitalism continues to erode humanness and historical context and it continues to dissolve the meaning of words. And it induces amnesia. Dylan can do Super Bowl commercials and hawk for poisonous soft drinks and its forgotten the minute after its aired. Because everything is forgotten.

The Clintons are the political mafia of the digital age. Petty, venal, and resentful. The crimes are large but their vision is not. The are the post literate political dynasty. And theirs is a vision born of appropriation. Hillary has been shaped by Kissinger but only symbolically, really. Her close advisors are people like Podesta and Jake Sullivan. And Sullivan is a sort of third generation dupe of Haldeman and Ehrlichman. It’s perhaps not useful to push this comparison too far. But the quality of mean spiritedness is what seems much larger now. Nixon was delusional, to be sure. And a red baiting cynical political climber. The boy from Whittier was not a ruling class insider, however. In fact he was never comfortable around wealth. His nightly dinner of Salisbury steak and cottage cheese always seemed a metaphor in some way for his class angst.

Chief of Staff H.R. Haldeman, 1970.

“I’ve spent the week greedily consuming the treats offered up by Wikileaks’s excavation of John Podesta’s inbox. Each day presents juicy new revelations of the venality of the Clinton campaign. In total, the Podesta files provide the most intimate and unadulterated look at how politics really works in late-capitalist America since the release of the Nixon tapes.

There’s a big difference, though. With Nixon, the stakes seemed greater, the banter more Machiavellian, the plots and counter-plots darker and more cynical.”

Jeffrey St. Clair

I’ve said something similar. There was a Shakespearian grandeur to Nixon’s delusions. Hadelman was a figure from Coriolanus or Othello. John Podesta is a wormy small Aaron Sorkin invention, at best. But maybe, in terms of the Nobel, the other way to look at it is to see the validation of bourgeois thought. Not all of the winners of course. Pinter and his brilliant acceptance speech was certainly an exception. But mostly that has been the tendency. Artaud wasn’t going to get one. Naipaul got one but Arundhati Roy didn’t. And that said, Naipaul for all his monarchist leanings is a very good technician of prose.

Raymond Geuss saw art in the 20th century following along one of two arteries. In the first… “Art followed its own laws which it gave itself: in particular, one couldn’t evaluate a work of art as art by such criteria as whether it gives a good imitation of reality, whether it has contributed to social progress, or by moral criteria. Usually this claim that art is autonomous was taken to mean that art produces distinctive “forms” that are inherently significant and worthwhile, and that the experience of these “forms” is in all relevant respects self-contained.”

Our Lady of the 7 Sorrows. Anonymous, apprx. 17th century.

In the second, the less Kantian and more Hegelian:

“To be more precise, art “in its highest vocation” must, according to Hegel, do two things at the same time:

1. it must tell us the truth or bring us to a correct awareness of our (natural, his- torical, social, and political) world;

2. by telling us this truth it must bring us to affirm our world as a fundamentally worthwhile place in which to live.”

Now, these are not absolute. And they overlap. And Adorno was aware of what might be a third, having to do with *expression*. But the point here is that the Young Hegelians found little to see that could be affirmative. And then Marx saw even less, and saw this as a result of a basically irrational economic system. Adorno would agree with Marx, but took it further. For Adorno there was something beyond just economic irrationality (and what one extrapolates from that) but a kind of historical malformation in humanity that itself helped create capitalism. The Nobel process is always one of validating (in their minds anyway) a kind of Enlightenment ideal of the pursuit of happiness. This of course got harder and harder the further into modernism one got. And I think there was a substitution for Enlightenment ideals with simply bourgeois respectability. Adorno and Horkheimer’s ideas on instrumental reason are very interesting here because the trend of capital was instrumentality and instrumentality meant a certain fungibility in humanity. And that, at least in part, accounts for the discomfort one feels when reading over the list of Nobel winners. I mean its depressing as shit. And I know I am only going to scratch the surface of the many reasons for that.

Isidore Ducasse (Comte de Lautreamont).

Everything was *for* something else. That was a key aspect of Adorno’s critique. Exchange value.

“If we accept for the sake of argument that our social world is evil, and that this evil has something to do with the dominance of instrumental reason, a number of immediate consequences follow for art. First of all, any form of art (or of religion or philosophy for that matter) that contributed to trying to make people affirm this world or think that life in it was worthwhile would not just be doing something unhelpful, but would be misguided in the most fundamental way possible.”

Raymond Geuss

And this is, increasingly probably, why all awards are depressing. They are depressing because they are predicated upon some vague idea of affirmation. And the truly affirmative resides in despair. And comes out of the slough of despond…as it were. The Western belief, a cultic belief, in happiness and the pursuit thereof, is so tainted with bad faith as to be unredeemable. Art is not meant to make us comfortable. Firstly because such comfort is a lie. Second, if that sort of bourgeois bromide were true then next years short list should be the writers of children’s books. And look, Id not bet against J.K. Rowling.

“There is a point in the nineteenth century when a secret nadir is reached. It occurs, but without anybody’s noticing, when a young man no one has heard of publishes, in Paris and at his own expense, a work entitled Les Chants de Maldoror. The year is 1869: Nietzsche is working on The Birth of Tragedy; Flaubert publishes L’Education sentimentale, Verlaine his Fêtes galantes; Rimbaud is writing his first lines. But at the same time something even more drastic is going on: it’s as if literature had delegated to the young son of the consulate employee Ducasse, a boy sent to France from Montevideo to complete his studies, the task of carrying out a decisive, clandestine, and violent act. The twenty-three-year-old Isidore assumes the pseudonym Lautréamont, a name probably suggested by a character in the pages of Eugène Sue, and pays an initial deposit of four hundred francs to the publisher Lacroix to have him print his Chants de Maldoror. Lacroix takes the money and prints the book—but then refuses to distribute it. As Lautréamont himself would later explain in a letter, Lacroix “refused to have the book appear because it depicted life in such[…]”

Roberto Calasso.

Louise Lawler, photography.

But one must be a bit more precise about all this. And this, in particular, in the idea of critical judgement. What Hegel called internal criticism. And this has to do with putting aside notions such as effectiveness or lessons of morality, or social relevance. For all that is lodged with an instrumental framework. Art has no use. But it does have truth.

“Even the most critical art gives us some pleasure, and to take pleasure in art is to be close to being open to the possibility of affirming the society in which this pleasurable experience is possible. The implication Adorno draws from this is that for art to be socially critical in an appropriate way, it must be aesthetically radical, i.e., it must radically and to some extent successfully struggle against its own tendency to affirmation. It can do this, Adorno thinks, only if it is formally negative or critical. Eventually this notion of being “formally negative” will be ex- plicated to mean that the work of art in question must internally subvert traditional aesthetic forms.”

Raymond Geuss

Karin Kneffel

Now defining truth is mostly impossible. But the process and rigor of that search *is* meaningful. And that is, at a certain point, the most radical intellectual and emotional position possible. The ascent of the bourgeoisie after the French Revolution found expression in what was still rather Homeric in a sense (this is too complex to deal with here) but by the start of the 20th century Western society under monopoly Capitalism had begun to trigger mass disenchantment — and with two world wars and a global hegemony today in the form of U.S. neo liberal Imperialism, society is now reaching levels of cognitive vapor lock (to sort of mix a metaphor). What Debord called generalized autism over fifty years ago is now exemplified in the growing infantilism and amnesia of the societies of the West. The U.S. today is one country of severe inequality, racism, sexism, and growing xenophobia. But it is also one of terminal addictions to distraction. To gadgets and screens and electronic communication. Community is reduced to social media. And friendship is a mouse click. Such societies do not produce, I don’t think, Isadore Ducasses’ or Artauds, and probably not even Cendrars or Genets. A writer such as Patricia Highsmith is neglected because she is too interior. Her characters do not look at lakes or lint, they are subtly inspecting their own existential crises in varieties of minute mental adjustments. But such adjustments are based on a tacit understanding that the world has become a hostile and unforgiving place.

Calasso, a great reader, writes of ‘Maldoror….

“It’s as if the innocuous anaphora, as taught in any textbook of rhetoric, had been blown up beyond all proportion and then set insanely adrift. There are at least two consequences: first, the reading experience is brought close to the essential nature of nightmare, something that lies not so much in the awfulness of the elements that make up a vision, but in the way they keep on and on coming back into the mind. And then the narrative is injected with senselessness, the same way a single word, if repeated often enough, becomes a mere phonic husk freed from any semantic bond.”

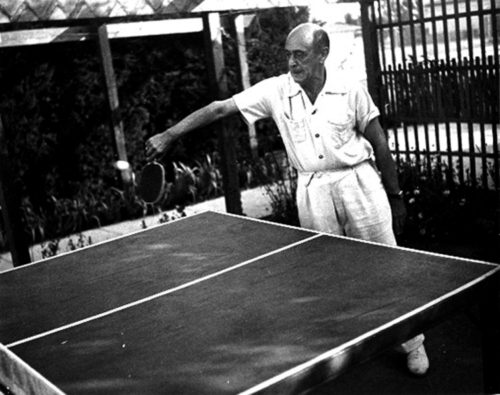

Schoenberg playing ping pong. California.

The earliest best precursors to modernism, the prophetic glimpse of monopoly capitalism, are found in Lautreamont and in Georg Buchner’s Woyzeck (published posthumously in 1879). They are the flip side of the same coin of disenchantment and horror. In 1925 Alban Berg wrote what I consider the among the greatest musical creations of the century with his opera (Woyzzeck) based on Buchner’s unfinished play. Adorno wrote of Berg (with whom he studied)…“The main principle he conveyed was that of variation: everything was supposed to develop out of something else and yet be intrinsically different.” The post literate culture is one that has lost that last part. Intrinsic difference is now not so much rejected as ignored. Unheard and unseen.

The changes in culture over the last forty years is seen most clearly in the loss of an audience for what Adorno would consider serious work. Now, yes, this is European art, the cultural form that developed from the mid 1700s hundreds on through the modernism of the mid 20th century. And one of the ideas contained in the new populism that has arisen in the post modern period is that of accessibility. And it is true that if one has never been exposed to, say, Bresson or Pinter, even, this work will appear opaque at best. The very idea of *entertainment* is relatively new. And over the last twenty years, say, entertainment has eclipsed almost everything else. There is good work being done today, but its hard to find. Or, at least it requires work to find it. Meanwhile the corporate owned media machinery of financial capital churns out a previously unimaginable amount of product. And this product is consumed at a stunningly high pace. It is non reflective work. The fears that Adorno felt (and Horkheimer and Marcuse even, and others, really, from Steiner to Calasso to a huge swath of more specialized art critics like Donald Kuspit) have come true. And it is increasingly difficult to talk about art in the way these critics spoke of high modernism.

Richard Long

“Since any art that does not attempt to satisfy its highest vocation (by criticizing our society in an appropriately radical way) is morally reprehensible, destruction of the autonomy of art would be unmitigatedly bad. One might argue that it makes sense to think that entertainment is inherently reprehensible only if the position from which art could exercise its highest voca- tion is in some sense accessible. If it isn’t, then the automatic devaluation of entertainment lapses. The question is what “accessible” means. For Adorno, as I have said, in the study of cultural phenomena impossible aspirations are in some sense just as important as realities. Art may reach for a kind of unique- ness it will never attain, to a fully non communicative autonomy, etc., even if those ideals are inherently unrealizable. I assume Adorno would apply a ver- sion of this doctrine here. Art is a necessary failure—it can’t fully occupy a high ground from which it could realize its highest vocation, but the vocation is nonetheless important, and as such gives us good grounds for the denigration of mere entertainment.”

Raymond Geuss

The rise of the warfare state runs parallel to the rise of domestic militarized police. And it runs parallel to the rise of empty cultural entertainments that favor jingoistic and infantile distractions. That said, it is not hard to view the white bourgeoisie that makes Hollywood film (since that is the dominant cultural expression today) unconsciously sharing their own anxieties. Zombie films increasingly (and all these pseudo reconstruction narratives that feature plagues and viruses and alien demons) as a fear of the masses. A fear of the poor. Zombies ARE hunger and need. And hence they are killed off in an almost absent minded manner. And killed off, in these films and TV shows, at an extraordinary rate. The affluent class favors self consciously prestige narratives that are about mostly the problems of the rich. It is the latest incarnation of the staring at lint genre. And it is work of astonishing narcissism. It is also, rarely, even slightly memorable. In fact it seems, increasingly, as if work is meant to be forgotten. This is the year TV has decided to reboot old franchises (Lethal Weapon, Training Day, The Exorcist, MacGyver, et al). The familiarity of the title is comforting. None of these shows has that much to do, really, with the original film or show, but that’s not the point. It is business. These are commodities. And the audience approaches them AS commodities. Shopping replaces discernment. Shopping itself is the art. The creative shopper. The role Adorno and others saw in culture is gone. And if people simply do not read, this is logical. People scan and sample.

“Wolf Lepenies finds in the figure of the melancholic a specific cate- gory of social rebellion. He identifies melancholia as the simultaneous rejection of both the means and the ends of socially sanctioned behavior. In line with Robert Merton’s (1968) ideas, Lepenies writes about melancholia as a retreat from and a total rejection of society due not only to the repression by way of social norms and interdictions but also to the total effect of society, which the melancholic experiences as a threat and as potentially suffocating.”

Esther Sanchez Pardo

The counter to the massive narcissistic and near autistic subject position is, I think, a kind of generalized depression or melancholia. Raymond Williams wrote that we should be…

“…looking, from time to time, from outside the metropolis: from the deprived hinterlands, where different forces are moving and from the poor world which has always been peripheral to metropolitan systems. This need involve no reduction of the importance of the major artistic and literary works which were shaped within metropolitan perceptions. But one level certainly has to be challenged: the metropolitan interpretation of its own processes as universal.”

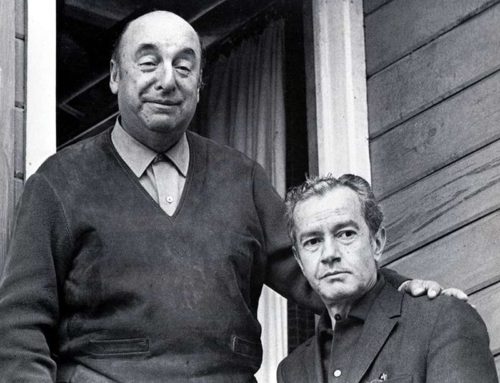

Pablo Neruda and Juan Rulfo (photo by Sara Facio).

One of the qualities of Ducasse and Buchner both was an identification with the underclass. Genet too shared this. In fact most of the writers I have mentioned share this. The aesthetic ideal of modernism, generally speaking, was a rejection of positivism and instrumental thinking. A rejection of conformism and homogeneity. And the dismissing of modernism today by a majority of post modern theorists is therefore not surprising. The post modernism that followed French structuralist thinkers became at a certain point an apologetics for social domination. Now, the original modernism ideal was compromised in different ways and a variety of contradictions ensued. Some in direct opposition to the original impetus. The psychoanalytical aspect privileged individuality and this founded a tendency toward self involved lint gazing in some quarters. Also the art market was developing and siphoned off energy toward commodity creation.

Critics like Shari Benstock, however, display a misreading of much mid century art when she writes of what she sees as the two main trends…

“…the urge towards polarities and oppositions (the proclamation of an adversary culture); the second is the effort to separate art from history (the proclamation of artistic autonomy). In fact, these pulsations are the same, and they lead to high modernism, which justifies continuity and exclusivity, in literary traditions. A dfferent kind of modernism, what I call avant-garde modernism (the excluded Other), announces itself as a rupture, a break with the past, and marks a cultural historical shift.”

Candida Hofer, photography (Banca de Espana, Madrid).

The avant garde was, at least in its major practitioners, never divorced from history. History was the nightmare from which humankind was trying to awake. And autonomy was also not separate from history. But such failures of critical writing are all too common these days. Sanchez Pardo, who I quoted above, mentions that Andreas Huyssen saw modernism existing in the shadow of anxiety. And that much I think is true. But Pardo is, like other contemporary critics, both right and wrong. For the medicalization of psychoanalysis led to a default acceptance of instrumental reason. And, simply, an inability to actually *see* the work being described.

In any event, the selection of Dylan is telling in the sense that it signals a final disregard for the craft of writing. I was never a huge fan of Dylan (and full disclosure I had a series of meetings with him in the early 90s on a film project. And he was fun to chat with about music, of which he knew a great deal but in the end he just disappeared, as celebrities are want to do). But I also was always aware of his being white and playing mostly black music, and when not black music he was playing the music of the rural white poor and white Churches of the South. And like many white artists who did this he made some half hearted attempts to make his audience aware of these roots. But not enough. And then, finally, much as I liked some of the music, I found myself unable to get fully on board (much like being unable to root for the Cleveland Indians with their current logo…even if I love some of the players on that team). But the point is not what I or you *enjoy*. It is about the history of a European institution that claims authority — Strindberg’s immortals — and who are in the end just a factory for compromised solutions. And in fact no awards institution can ever be other than that. And no artist who believes in the radical nature of aesthetic resistance can accept pimping for General Motors. And no artist can accept such awards without formulating statements that reject the very premise (think Pinter and Sartre and Tolstoy).

Juan Rulfo, photography.

There is an obscure film, that for some reason I thought of while writing this; Este pueblo no hay ladrones (There are No Thieves in This Village) made by Alberto Isaac in 1965 and based on a Marquez short story. The reason it is of interest is that the cast includes Juan Rulfo and Luis Bunuel (as the town priest…see below). Rulfo was a very fine photographer, but his fame rests on his novella Pedro Paramo, one of the greatest books of the century I think. Somehow it is seems appropriate to mention Rulfo here, and that novella, because while Rulfo is known, he is hardly famous. He was never a celebrity even in Mexico.

“All great writing springs from le dur désir de durer, the harsh contrivance of spirit against death, the hope to overreach time by force of creation.”

George Steiner

Art is inextricably tied to mortality. Entertainment is a kind of denial of death. And the political mirror of this denial is fascism. The sadistic cruelty — a sexual deformation, is tied in with the lust of greed and whatever one means by power. Great writing is not amusement. It is an engagement for the reader that is always exhausting. Reading bad books on airplanes makes sense. One wants no part of thoughts of mortality as one takes off. Here is another quote from Steiner…

“The highest, purest reach of the contemplative act is that which has learned to leave language behind it. The ineffable lies beyond the frontiers of the word. It is only by breaking through the walls of language that visionary observance can enter the world of total and immediate understanding. Where such understanding is attained, the truth need no longer suffer the impurities and fragmentation that speech necessarily entails. It need not conform to the naïve logic and linear conception of time implicit in syntax. In ultimate truth, past, present, and future are simultaneously comprised. It is the temporal structure of language that keeps them artificially distinct. That is the crucial point.”

Donald Judd

Rulfo’s novella is about death. Much Mexican art is overtly death infested. That is its beauty. Steiner said something else a few pages later…

“With Wittgenstein, as with certain poets, we look out of language not into darkness but light. Anyone who reads the Tractatus will be sensible of its odd, mute radiance.”

This was something I had always felt and was heartened to read. For it is Wittgenstein’s sensibility that is so important. For him, most of the world, or the truth of most of the world, is silence. It is contemplation. The great works of Islam and Taoism and Vedic writing are all about silence and death. Beckett was about that, in his way, and so is Rulfo. The American culture of the 21st century is about noise. Noise and how it helps one to not remember. How it helps us not to remember that we can’t remember. Noise is there to distract and with it has come, in the U.S. anyway, a neurotic involuntary laughter. People laugh constantly and for things I don’t understand. Comedy shows outnumber drama in popular culture. Steiner notes also that mass media has reduced language, or something like 90% of it, to thirty four basic words. In Shakespeare’s time it was something like five times that. People talk more but repeat themselves more. Listening to the political theatre of the current election is to reduce one’s vocabulary even more.

Here is the opening paragraph of Broch’s Death of Virgil (translated by close collaborator and friend Jean Starr Untermeyer)…

“Steel-blue and light, ruffled by a soft, scarcely perceptible cross-wind, the waves of the Adriatic streamed against the imperial squadron as it steered toward the harbor of Brundisium, the flat hills of the Calabrian coast coming gradually nearer on the left…

Of the seven high-built vessels that followed one another, keels in line, only the first and last, both slender rams-prowed pentaremes, belonged to the war-fleet; the remaining five, heavier and more imposing, deccareme and duodeccareme, were of an ornate structure in keeping with the Augustan imperial rank, and the middle one, the most sumptuous, its bronze mounted bow gilded, gilded the ring-bearing lion’s head under the railing, the rigging wound with colors, bore under purple sails, the festive and grand, the tent of Caesar. Yet on the ship that immediately followed was the poet of the Aeneid and death’s signet was graved upon his brow.”

another splendid piece–and what about Margaret Atwood?

I do think that Toni Morrison’s acceptance speech was provocative enough to break someone out of their manufactured life for at least a bit & I’m a huge fan of JM Coetzee’s early work, especially parts of In the Heart of the Country & Waiting for the Barbarians. He’s actually the writer whose work caused me to question some of the structures we live in, much more so than the multi culti oppressed person books I had to read in college.

I would also say that it’s interesting Leonard Cohen didn’t bubble up. Compare Beautful Losers to any other book written by a well known musician.

Atwood is one of the most boring writers that ever picked up a pen and most Canadians cannot get through her books to the end. There are a number of great Canadian writers but she is not one of them no matter her reputation (and how she got that is worthy of an essay). However, I digress from my single cavil since I disagree with much in this essay though masterfully written as usual but one point I have to raise; and that is about Momsen. Sure there are always other writers who deserve these prizes, the whole concept is absurd except that it does at least for a few minutes bring literature into the lives of the majority who do not read, that it is something important, but Momsen was not undeserving. His A History of Rome is a work of art as well as intellect and he was justly world famous when he was awarded the prize. I think Zola should have been awarded the prize in 1902 – no one compares with him except Hugo-but Momsen can write.

@jay….yes, glad you mentioned Coetzee. There are always people one forgets.

Im not a huge fan of atwood, but ive not read her in a long long time. Djuna Barnes is worth a mention, so is Paul Bowles. And Cesare Pavese. In fact Pavese is hugely underrated and overlooked. Borges probably deserves a mention at least. But I was thinking…..Pasolini looms as a very interesting figure. Poet and filmmaker and political writer as well. Id give it to Pasolini in a second. Id make a case for Robert Louis Stevenson, too, though he died before the turn of the century I think. Oscar Wilde and Jack London. I mean one can keep coming up with names. Iris Murdoch and shit, Mark Twain. I mean Twain died in 1910. How was he not given one?

@chris…ill check momson. Not looked at him, as well, in ages.

I also like your mentions of Robert Bly. I grew up in the little town in northern Minnesota where he’s maintained a place and his writing cabin and I went to same high school as his kids. Most townspeople didn’t know what to make of him or were too reverent. He did a free annual reading at a local church and maybe 30 people would show up. I was pretty much the only local student who would go. Being 12 or 14 and listening to Bly read his poems and interpret fairy tales is experience that had a big impact on me. I also remember when I ran into him the summer before I went to college. He thought my choice of Dartmouth was horrible (when I took creative writing there from poet Tom Sleigh, Sleigh said once he thought Bly was a huckster). Also, speaking of lake gazing, another influence was Robert’s ex wife Carol, the late short story writer and essayist. She used to ski (asking politely unlike some people) on my family’s tree farm and had a place on the same lake… She also thought I made a bad college decision. Her anthology Changing the Bully Who Rules the World is a gem.

Sartre declining the ’64 prize: “The writer must therefore refuse to let himself be transformed into an institution, even if this occurs under the most honorable circumstances, as in the present case.” http://www.nybooks.com/articles/1964/12/17/sartre-on-the-nobel-prize/

yes glad you mentioned carol, Jay. Carol Bly was a terrific writer actually. As for Tom who? The fact is a lot of academic poets dislike bly. He refused to teach at universities. To take a full time position doing that. I remember him saying it was a kind of death and that it ruined Lowell as a poet.

Bet next year will indeed be Rowling or Neil Gamain or Joss Whedon….

http://www.nybooks.com/daily/2016/04/16/syria-now-writing-starts-interview-adonis/

Must have had big fights about him. Splitting the judges.

So we’ve fought about Adorno and modernism over the years, I don’t want to start again… but here’s something. I was having an interesting discussion with tanquista about Lanthimos’ The Lobster. Have you seen this? It;s a movie about generalized autism. Like a lot of movies, art house and popular, of the last decades its got hideous violence treated as amusing. The rationale is “its supposed to be uncomfortable.”….as if this is just given, that art should repeat discomfort of other experience, and that why this is so should be immune from investigation (it’s like art takes on the task of criticism, and then forbids criticism to be critical, demanding criticism become the endless affirmation.) I was trying to figure out if there is some generational things, or if age itself is the difference…like when I was tanquistas age I could watch Salo. But the stakes in that film and its endeavor are very clear. As with Seven Beauties. The Lobster’s violence is attempting the literalization of psychic pain of the romantic search for those immersed in autism (one’s own or only that of others); the literalizing is the logic of the movie (single one feels less than human; like an animal; expelled from the dating world one is living feral in the woods…

trying to modify oneself to suit another is a self mutilation, literally, etc) So the film is wry, not funny but not serious, camp and snark mixed into this new pose of refusal of language..and it stages the incapacity for figurative languaeg and the smbolic (crude allegory is accessible cause one to one codes, but not symbol). So the film is obeying all the criteria for art’s responsibilities as far as the modernist rule book goes. But one can’t help but ask for the justifications for this rule book be re-examined. Why should massculture products be machines of epeated pain and discomfort. Isn’t the commerce in these aesthetic machines a way of acclimating and after all affirming this discomfort and pain, not by disguising it as pleasure but as actually creating conditions for it to be the only experienced pleasure (as if nothing else a break from anxiety due to mere attention-paying). Anyway, I’m wondering.

The Clinton Trump Presidency, The Dylan Nobel, belong to this Lobster world pretty literally; from the posture of one you can’t discern the absurdity of the other anymore.

Which strikes me as affecting St Clair there…isn’t he being completely ridiculous treating some quasi private chattery emails about spin and pr with the campaign manager as if they were classified top secret minutes of policy making meetings? It’s like treating Bob Dylan as literature of the impact and gravity of Petals of Blood. Taking the daily blithering about pr for ruling class management. This stuff is for public consumption; he’s discussing with her how to talk to her business world donors and lower level politicians. It has nothing to do with imperial decisions. It’s te same kind of generalized autism…he’s caught up in this idea there is nothing behind the screen or off screen. (it merely appears, it is not produced as a screen)

“a Canadian international bestselling author who writes in the coveted ‘people looking at lakes’ category”

A snarky extrapolation of “shoe-gazer” there. Cheap, easy, and bulletproof because it’s zingy.

Munro writes as a refugee from something overwhelmingly oppressive that her honesty compels her to admit she brought with her, that it’s in large part what shaped her and she’ll carry it always, through any escape.

It’s class as ethnicity – she’s entered the Nobel world from outside, from below, for all her adoption by bourgeois sentimentalists.

“Noise and how it helps one to not remember. How it helps us not to remember that we can’t remember…”

Her work is full of a rigorously honest contemplative quiet, a stillness if not silence, that refutes that noise and remembers.

–

If the prize was to be given purely for literary integrity and achievement I’d put Thomas Bernhard up top.

But Pynchon for me personally, for what the work *does* rather than for what it *is*.

My issue with modernism isn’t so much modernist art itself, much of which is first-rate. That’s not the issue. It’s rather the idea that artists working today should have to feel obligated to operate “in its shadow” as if someone can’t be allowed to directly draw inspiration from ‘non-modernists’, whether they be Balzac or Rembrandt or whoever. I don’t think the history of art is as linear as that. I know John won’t entirely agree with me. I just don’t think artists should have to feel stifled by modernism’s ‘shadow’, but that’s not meant as a critique of its creative output. John often complains the lack of first-rate artistic output these days, and frankly, I think modernism’s ‘shadow’ is part of the problem, because artist’s feel pressured to be ‘experimental’ which can ultimately be stifling.

@molly,….yes I was only barely half kidding when I suggested rowling. And im sure whedon is shortlisted too. This is what the Dylan award signals. The onset of officially validating the idea of post literate popularity as some new form. Now, I think the issue with the Lobster (which Ive not seen but i did like Dogtooth rather a lot, actually) is what we mean by pleasure. I agree there is this new weird state of generalized almost autistic processing but I wonder what pleasure means here. I dont experience pasolini as any sort of re-experiencing pain or discomfort. He aestheticized something to do with how domination affects us. But i think we have to decide what these words mean. I mean I agree completely with the formula you describe…criticism that isnt allowed to criticize. And maybe it was david lynch ushered this in, to some extent. His films are not critiquing anything. ANYTHING. They are a facsimile of a critique. If that. The sadism of a gaspar noe is certainly different than a pasolini. And I think adorno had another suffering in mind, certainly.

But im not sure modernism had that rule book. But there were several modernisms in a way. But your point is taken and its correct I think. Somehow though, this new whatever it is…post postness….loses history, because that is handed down through language. And with it memory. I just read where A levels in england will no longer include art history. In the US ive heard that sweeping cuts to these sorts of classes are coming. This is all happnening over the last thirty years. The end of culture as we know it. I mean it really is.

The st clair was interesting because id thought the same thing about nixon. The rest…well…i am increasingly getting the feeling of being handled. All the time. From all corners. I dont know what is meant to be consumed, what isnt…if ANYTHING isnt really….its about timing. But i honestly dont know if i can tell what political reality is anymore. At least at times.

months go by and not a single comment. But write about an award and people come out to complain ….@michael griffin….because they liked someone you didnt. I m sorry but there was no zinger or whateverthefuckever you think it was. Im fine with liking munro. I find her paralyzingly boring. But thats me. I think that the sort of novel she writes is very hard to write anymore. Just because its been written so often. Bourgeoise sentimentalists….yeah, well, your words, not mine.

I like michael ondaatje\s Collected Works of Billy the Kid….and in a way it stands for something of a shift. Not the one molly and I are speaking of….but it does register as something else in terms of narrative. But memory is involved. But my point is…..i KNEW…i KNEW comments would come in this posting. Guaranteed.

I should add, that while I find it predictable to get comments, i also understand it. I mean i bothered to write about it. I think the previous four or five winners were feeling sort of boring to the public…or what the nobel committee thinks is the public. I also think Munro was the best of that group…by a rather substantial degree. However….i wonder if this isnt sort of dovetailing into this issue molly raised.

Munro’s virtues are in her technical skill. I wish it were more silent however.

But that is this question of (per molly) of literalizing …..and as i say, ive not seen the lobster, but i do see this other places. Its a confusion of category in a sense. Its not quite grasping intuitively what alegory is, or even symbol. Its subtle at times….but it is there in so much popular product now. One of the reasons I think Stranger by the Lake is so great a film has to do with the way it expresses the ineffable without literalizing anything at all. And the language…though sparse…is very significant. Its a bit like a weird gay porn version of robert musil or something.

@John Steppling

While I am a big fan of “black music” (hate that term), I think you overstate black influence on European popular song. You write: “Even Dylan would probably admit that Smokey Robinson should have been in line ahead of him. …

Still Dylan deserves the recognition. He’s the greatest white blues singer and probably the best songwriter of the rock era.” Dylan experimented in many styles, including country, but his best compositions had zero black influence (eg, Visions of Johanna). (Love Smokey, but his music–like most Motown–did not age well. Try listening to Shop Around.) IMO what makes popular music so great is that it’s composed of sui generis geniuses who are simply being artists–from Taj Mahal to Ray Davies. I think John Lennon was the person most responsible for creating the idea that a mediocrity like Chuck Berry (saw him in Boston and he was great but Frank Zappa blew him off the stage) was central to European pop.9

Well personally, I don’t think artistic greatness is something that can be reduced to concepts. Great art occurs just as much in the execution as it does in the conception, in my opinion at least. Sometimes, when taken to an extreme, allegory can become a crutch of sorts. An artist can enslave themselves to a certain theme or concept they want to explore, and so every gesture within that work only winds up serving to reinforce a preconceived concept or ‘idea’. In short, the work becomes a vehicle to express an abstract intellectual concept but it does nothing more than that, and so it ends up lacking any sense of spontaneity or human feeling. It may explain why in the long run a Dostoevsky or a Balzac or a Degas, or even a Jean Renoir may prove to be enduring than figures like T.S. Eliot and Stravinsky. The works of Renoir and Dost transcend ‘movements’ in art. Eliot does not. This I think is precisely what the concept of mimesis is all about, art providing us with an acute sense of the quotidien or lived experience rather than merely delivering concepts. I’m not dismissing the allegorical. All art is by definition allegorical to some extent since it can never completely replicate true reality. So perhaps an artist just needs to have faith in the fact that the allegorical is already embedded in the DNA of all artistic expression. I don’t know…

that was st clair who said that, don, not me. Dylan learned from woody and came up through that greenwhich village folk scene. But he did know american music. I enjoyed talking with him a lot. I remember we talked long and intensely about the value or lack thereof of Hank Snow. But he did borrow a lot from black music. If just in a secondary way. I mean american music is, regardless, black music. It just is. But dylan’s popularity is from another tier altogether i think. I remember being entranced with that small riff in All the Tired Horses (1970 i believe). But again, we’re talking presumably the most prestigious award in literature. And he isnt a great writer of literature. So it signals a shift. But id argue, regardless of dylan’s intrinsic value, that american music is black. From leadbelly to ellington to monk and bird and miles and coltrane. Hank williams and woody notwithstanding, or cisco houston (who dylan loved by the by and where i think he got his current mustache from) or dave van ronk or whatever. James Brown should get the award before dylan. Id be fine with that honestly.

I haven’t listened to much Smokey, but speaking of Motown, I’d say Marvin Gaye has aged just fine (in fact, I’d say Gaye and James Brown have aged better than an act such as The Doors, although Brown isn’t Motown), and I’d hesitate to dismiss Chuck Berry as a mediocrity.

@ Remy….since when have artists not been working under some shadow? I think there is an argument to be made that because of the shadow, art can exist, whether that shadow be oppression or illness or heartbreak or modernist critics….

And yeah, history is difficult, admitting to one’s history often fucking sucks. But modernism happened and if one is not in ignorance of that fact, then it might become a part of what the “artist” understands as their history too. That ‘shadow’ can create a tension worth working with. But maybe sometimes one has to sit in the agony of that shadow before it ceases to merely hover over us, and begins to move through us… OR sometimes it is worth it to sit in the shadow of the implied shame and self-judgement at not meeting the dead-white-guy-modernist-critics expectations. Failure. Maybe those modernists are so damn useful because they make it impossible to succeed. I once had an acting teacher yell at me that I needed to “make the impossible possible.” It seems to me that all artists have to do that somehow.

As for the loss of the serious, yes it’s lamentable, but what’s the cause. That’s the question. Personally, and I realize this may be contentious, but I think the Adornos and George Lucases of the world are both to blame. Adorno didn’t seem to think great art transcended the ‘radical’, and perhaps that’s where I part ways with him, the idea that art’s sole raison d’être is to be ‘radical’ and ‘disruptive’. That may have been true during a specific historical epoch characterized by certain political realities, but is that true across all space and time. I’m not sure. Constructing these oppositions between supposedly ‘bourgeois’ artists like Sibelius and Shostakovich on the one hand hand and ‘radicals’ like Schoenberg and Berg on the other aren’t very productive, especially in a world where most people’s cultural knowledge barely extends past The Godfather and The Beatles. I would imagine Shostakovich didn’t necessarily concern himself with what was in vogue among the intelligentsia of his day and simply wrote the music he wanted to write. This isn’t intended to bash a Schoenberg. It’s similar in film with Godard the ‘radical’ on the one hand and Kurosawa the ‘bourgeois’ director on the other hand. These sorts of purist binaries lead to the polarized cultural atmosphere you rightly lament in most of your posts. Have Shostakovich and Kurosawa been co-opted by the middlebrow of today, emphasis on *today*, not the middlebrow of 1955? Personally, I don’t see it. The Godfather on the other hand is still easily assimilated within the contemporary middlebrow cultural lexicon. Co-optability is defined just as much through the passage of time as it is at the moment when a work of art first appears. And I say this as someone who has the utmost respect for many of the ‘radical’ artists, but oftentimes I think what’s great about a work of art at least to some extent transcends the ‘radical’ aspects, which are often largely a response to certain immediate historical/political conditions, which aren’t necessarily permanent, or at the very least don’t exist ‘in nature’. Just as a disclaimer, I love The Gospel According to Matthew just as much as I love the first movement of Shostakovich’s Eighth Symphony. Adorno was certainly insightful about a lot of things. I’m just not sure every last value judgment of his on every last artist need be construed as the gospel, since like anyone else he came of age at a certain time in history within a certain culture, and that was bound to affect his aesthetic biases, just as my being someone from Queens who came of age in the early 21st century is bound to affect my sensibility and inform some of my biases. I didn’t grow up in a ‘cultured, bourgeois’ family in Interbellum Europe, even if I do now happen to live in Europe, so I can’t possibly be informed by the same formative experience he was, even if I admire much of the same art he did.

@calla

I actually agree with you. Of course, artists are always working under a shadow. I don’t know. Maybe I didn’t express myself very well. I’m not saying “turn your back on James Joyce and just resort to regressive forms like Jonathan Franzen”. But the modernists were building upon pre-modern classical forms, so any great art I think is informed to some degree by all the art that preceded it, not just that which directly preceded it, so surely someone writing fiction today should feel free to draw inspiration just as much from Tolstoy as from Proust. The fact that they’re both read or at least acknowledged today means they both still matter. What I reject or at least question is the idea that the achievements of a Kandinsky “date” a Degas or a Cezanne.

Also, I think John would argue that what makes it hard to succeed as a serious artist is the dumbing down of culture not just the ‘shadow’ of modernism, and I would say he’s right, but counter-intuitively I think the “dead-white-guy-modernist-critics” expectations are partially responsible for that dumbing down, leading to the polarized cultural atmosphere I alluded to earlier. Naturally, this is a thesis that’s rather difficult to flesh out in an internet thread, but this modernist orthodoxy leads to the likes of Lynch and Warhol I think. It also fosters the MFA glut as well as cloistered environments like the international film festival circuit with the institutionally-supported and manufactured ‘high art’ of people like Bela Tarr and Weerasethakul.

The modernists “making it impossible to succeed” is what creates Warhols and Lynches and Noes.

Or maybe I’m just a frustrated twenty-something who hasn’t yet figured what form my writing endeavors should take. I honestly don’t know.

I apologize for a string of comments since thoughts just keep coming to me. But maybe the problem is the English language itself, and maybe each language’s literary tradition has its own timeline. Samuel Beckett said he chose to write in French rather than English, because it was easier to write in the former ‘without style’. As someone who speaks both English, my native English, and French, and having attempted ‘creative writing’ in both languages I can see exactly what he means by this or almost maybe. I won’t oversell myself, at least not yet. 😉 The language of some of the greatest post-modernist, not to be confused with “postmodern”, English-language writers like Faulkner and Cormac is almost ‘anti-literary’ in a sense. The English-language almost makes it too easy to indulge in the ‘poetic’ when attempting to write fiction, since ‘style’ is built into the French-language already in a way it’s not with respect to English.

Ha. Indeed. I think everyone should read Carol Bly. And she was so wonderful and kind. But always sharp (in all its meanings).

The quote I remember from Robert is “I’ve had many offers but why would I go be poet in residence at some university when I already have a home in Moose Lake Minnesota?”

I actually do think some of Tom Sleigh’s poetry is very worth reading. He’s been back at Hunter College for some time. He hated Dartmouth but it was a job until he started winning big poetry prizes…

Poet, dramatist, essayist and academic, who lives in New York City. He has published eight books of original poetry, one full-length translation of Euripides’ Herakles and a book of essays. At least five of his plays have been produced. He has won numerous awards, including the 2008 Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award, worth $100,000,[1] an Academy Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters,[1] The Shelley Award from the Poetry Society of America,[1] and a Guggenheim Foundation grant.[1] He currently serves as director of Hunter College’s Master of Fine Arts (MFA) program in Creative Writing. He is the recipient of the Anna-Maria Kellen Prize and Fellow at the American Academy in Berlin for Fall 2011.

John, the zinger in question was Shephard’s. The “shoegazing” was a response to that as well. It just seemed easy and safe. Any critical fire your direction was ricochet.

I’m not defending Munro’s Nobel by any stretch. Since Kissinger’s bizarre anointment I’ve got nothing but a sidelong askance view of that process and product. And Obama, I mean Jesus.

And nor defending Dylan’s award, though it seems fun, humorous and apocalyptic simultaneously. I have a lot of gratitude for what his voice has been in my life. But Stockholm’s praise doesn’t carry that.

Nothing in the chemistry of what my experience of literature is has ever seemed finished. It’s volatile, unstable, every year what thrills me has changed, moved somewhere – I’ve just never been able to scorn my younger less developed self. I can still read some pulp sci-fi with the eagerness and appetite of my adolescence. There’s a kind of loyalty to that, in that.

Maybe the dynamite angle would be productive in discussions of the Nobel selection process. A century-long controlled demolition of the increments and symbols of Western Civilization as they appear, destruction through reward.

A little surprised you let that Thomas Bernhard ref slip by. What I’ve read of his seems to have more than a little in common with your aesthetic as presented here.

And as I said before, the images you bring are wonderfully instructive and consistently gratifying.

So thanks for the work, and sorry for irritating you

fair enough

Well said. Problem is, most of the world is engaged in struggle and music is the literature available to express many things (see Cuba’s innovations) just based on what is available to people. But Dylan fits nowhere in that thought, I am not able to fully understand him but I know he is not greater than delta blues, jazz, post-revolution Cuban music. That’s my feeling, but I’m just thirty. I don’t want to denigrate peoples expression but I do want to understand how it is promoted and organized by Empire. Or suppressed.

That said Ngugi is a fantastic political writer that hasnt won– I heard a few rumblings about him this year.