Willem de Kooning (1948)

“The making of coffee, for example, performed unthinkingly every morning for years, can suddenly become profoundly

evocative when the gesture conjures the presence of a person no longer there.

Likewise, a child’s toy brings to mind a moment forgotten. The winter light illuminating

a sofa reminds the dweller of a conversation three years earlier. The

presence of these physical objects, of the bodily routines, of the light and the smells

of a home, enables the conjuring of memories inscribed in those places, sensory

impressions, connection to the past, and even identity in the present. “

Leora Auslander

“You are what you drive.”

Clint Eastwood

“If psychoanalysts could discuss relations with people as “object relations,” it certainly

seemed possible to view things as role models or socializing signs.”

Mihaly Csikszenthmihalyi

“My experience is what I agree to attend to. Only those items which I

notice shape my mind – without selective interest, experience is an utter chaos.”

William James

As far back as the early 20th century, sociologists like Georg Simmel noted that the cultivation of technology had become a source of internal conflict. That human mastery was serving to distance experience from our sense of self. Technique was replacing direct intention. But he also noted that this idea of mastery itself was weighted toward that which we chose to give attention. What evolved through the observations of Simmel and others was the idea of the *sign*. This was the semiotic discipline, in a sense.

“Viewed as signs, objects have the peculiar character of objectivity,

that is, they tend to evoke similar responses from the same person

over time and from different people. Relative to other signs such

as emotions, or ideas, objects seem to possess a unique concreteness

and permanence. Obviously, this characteristic of objects is

grounded in their physical structure so that an artifact from an

ancient people can still convey an image of the ideas of that culture

even though there may be no record of how those people

spoke or what they believed.”

Mihaly Csikszenthmihalyi

The real issue though, was man made objects. For this category owed its very existence to human intention. And this leads to something else, and that is (per Csikszenthmihalyi) that authority is born, on one level anyway, from the signs associated with it. The chair and robes of the Judge, or the crown of the King. And the word *invest* is here very interesting. For under Capitalism, to invest means to expect a return. Even at the level of meaning. I invest meaning in the Judges robes. And I trust the consistency of this invested meaning. And part of contemporary mythology is that objects, even man made objects, by virtue of their object-ness, are neutral. If bombs are designed to kill, they are still perceived as neutral objects. It is the General and soldier who employ them that do the killing. And to a degree this is true, but only certain people have access to bombs, want to have access to bombs.

Danny Lyon, photography.

Now this becomes an obviously complex discussion, but for the purposes of this post, the forgotten realm of the meaning of objects has to do with class perceptions, with social training and how these factors *invest* various meaning in day to day objects. This is clear in how members of dominant classes will buy the same kinds of things; share the same aesthetic perception. They share the same taste and validate that taste through control of information technology. This is clear, although in often less obvious ways, in entertainment. Reviews of new TV shows, for example, are surprisingly uniform. And yet, reviews often are superseded by audience taste. A show like The Divide, was uniformly praised, and yet cancelled after one season. There was no audience for it, ratings were very poor. So in one sense, the critics praise didn’t matter. And it didn’t matter because the audience was already trained to reject themes of defending the innocent. Trained to reject the theme of a flawed criminal justice system. Other shows, despite bad reviews, become hits. For the same reasons (meaning, the audience is predisposed to embrace certain themes).

Dahn Vo

“For a certain period the conquest of extraterrestrial space seemed

to be a new direction of development for capitalist expansion. Subsequently

we saw that the direction of development is above all

the conquest of internal space, the interior world, the space of the

mind, of the soul, the space of time.”

Bifo Berardi

The colonizing of consciousness, then, is cognitive capitalism (per Jussi Parikka). Global economic depression creates psychic depression in a sense. It’s dangerous to follow this logic too far because there lurks something reactionary in it. But, there is a process of intellectual exploitation going on.

“…that this exhaustion should not be mistakenly read as only about the mental

powers of the rather still privileged informational workers, and that digital

machines are themselves not understood as infinite or immaterial

either. Instead, digital culture is also sustained by the rather exhausting

physical work in mining, factory production lines, and other jobs that are

not directly counted as part of “cognitive capitalism”—and the machines

themselves grow obsolescent and die, their remains leftover media-junk

and future fossils; and ecological resources are exhausted

as well, part of the increasing demand for minerals and other materials

for advanced technology industries.”

Jussi Parikka

Romauld Hazoume

The idea of enclosure then is both psychic and material. Resources are exhausted and thinking is becoming exhausted (a theme of Bifo’s, actually). But this idea is directly related to what Jonathan Beller calls *computational capitalism*. And germane here is that fascism both prophesied and helped invent computer technology. Computation then, from this angle, is the social intention for computational objects. And there is another aspect to what Beller says (and what Marina Gržinić, Šefik Tatlić write about) and that is that computer generated imagery (and I would argue aesthetics is both affected, and partly a cause) depends on the computational power of a machine (and Enzo Traverso sort of touched on this in his book on the rise of Nazism and that WW1 was the watershed for this fascist machine dream in that it was the first industrially planned war, and the first anonymous war). So the imagery of techno capitalism is premised, in a sense, on computer graphics and various registers of fast computational power, but also, perhaps most importantly, is creating the off-screen of massive digital algorithmic financialized scorekeeping. And the offscreen is always the unconscious anyway. And in any story, any play, the unconscious is happening off screen or off stage. And so it is here with the 21st century assault of computational capital.

The logic of computational capital is linked at its core with the primal idea of mastery that is embedded in attention. The computer as social programmer (this is Marina Gržinić, Šefik Tatlić again). The post modern imaginary is, then, a kind of digital imagery that masks the actual penetration of consciousness by this hyper-rapid computing that basically creates the *world* of things and objects that are experienced, increasingly, in the new unreality.

Frank Benson

The aesthetics of computer generated imagery is only the surface after effect of a sort of new Capitalist division of markets, many of which are part of the attention economy (per Beller, again). Cognitive and intellectual activity is then transformed into temporary work sites — the subjectivity of financialization. Hollywood is increasingly about the creation of new markets, new kinds of attention (or pseudo attention I would argue) in which the mental staging area that Lacan and others have noted (and really Benjamin and Adorno, both suggested was being altered) is now the digital sound stage, but one whose engine is the computer. Narratives then, or those manufactured by Hollywood, involve somehow the penetration of Capital into new markets ( Marina Gržinić, Šefik Tatlić mention Slumdog Millionaire, but there are countless examples…Wolf of Wall Street, or TV shows like Suits and the new fringe drama Startup). The post modern imaginery is then one of circulation, and abstraction. Art is not linked anylonger (or rarely) with suffering. It is cleansed of underclass vision and voices, and operates more on a level of android efficiency. As Donald Lowe said, the graphic image is now photographic. And this constitutes, by mid 20th century, the definition of *realism*. But the photograph is somewhat decontextualized, and it also favors detail, and often detail unseeable by the human eye (though visible through the technical eye). And this goes back to the pre historical notion of man made objects and their neutrality. Everything ‘realistic’ is neutral.

Baudrillard saw that ideology was not a free floating imaginary following after exchange value. It was the very operation of exchange value. But all this returns to this idea of the transformation of attention.

“This interface between spectator and social machinery, realized as ‘the image’ (which

received rigorous critical analysis by the Frankfurt School, the ‘situationists’ (Debord)

and feminist film theory), has been generalized to the omnipresent screen and is also

being extended to the other platforms and senses: ‘the computer,’ ‘the tablet,’ and ‘the

cellphone’—all of which appear to be increasingly similar. Now, of course, the program

is being extended to sound, smell, touch and taste—music and game sounds, obviously,

but also programmed shopping environments (which themselves extend into the urban

fabric) organized by architecture, texture, scent, and arguably salt, sugar and fat. These

innovations and their convergence (towards the omnipresent, omnivorous and indeed

omniscient cyber-spatialized mall-military-prison-post-industrial cosmopoplex) bring

about new levels of interactivity as well as new and ever more elaborate metrics for the

organization and parsing of attention-production.”

Jonathan Beller

Mira Schor

The screen life of the public is realistic because it manufactures the imagery of neutrality. The viewer is always outside the story in a way that one is never outside it in reading. And it was Debord who first sensed what was coming in terms of the manufacture of social narratives that would help gather institutional attention from world corporate media. Mass violence started to reflect both an intuitive sense that spectacular imagery was needed, and also to duplicate the lurid tales of Madison Avenue PR firms when employed by Western governments. Tearing babies from incubators didn’t happen, it was dreamed up on Madison Avenue, but to some fundamentalist cell it is looms as an effective bit of spectacle. But this is the obvious end of colonizing consciousness, whereas the more pernicious dimension is how the very activity of coding is anathema to non-capitalist ideology. The computational dream machine is one designed for fascism, and it operates as an intellectual simulacra gestapo.

If Donald Lowe saw visuality in bourgeois aesthetic evolution as replacing touching and smelling and hearing, I would probably amend that to read that a certain kind of visuality replaced the narrative and emotional experience of empathic suffering. And this visuality was one of cleansed antiseptic anality and of voyeuristic sadism. The post modern was the age of waning historicity (as I think Beller put it) and today, in the post post modern the digital has computated the off stage unconscious so that it is no longer *off* anywhere: it is a non place, an enclosed zone of intellectual internment. And this connects back to what Bifo spoke of with the generalized emotional recession. A collective depression that is linked to financialized depressions.

Russell Tyler

Now, during the Paris Exhibitions — a period from the early Third Republic — there was an emphasis on cataloguing and the exhibition of very thorough classificatory practices. And all of this to focus knowledge as that which is verifiable by visuality. The front edge of modernity (or late modernity) reflected in those Exhibitions was met with virulent opposition in the form of Catholic conservatives who felt the highest values in life were found in the unseen. The exhibitionary and the idea of comprehensivness were one in the moral instruction found in the educational justification for colonial barbarism. The catholic reaction was not against barbarism and cruelty, or even comprehensive learning, but only against the vulgarity of the display which was felt to be akin to seduction. Hence the influence of this repressive religious sensibility was felt in the increasingly, over time, sober institutional demeanor of the Exhibitions…and later, more, the ending of exhibitions in favor of growing museum formats and University scholasticism. The repressed white male colonial overlord was also the gentleman curator of various institutions of learning and culture. The exhibitionary became repressed, but didn’t go away. How much one chooses to focus on this primal computational aspect of ur-capitalism, or seeing it from as the fall out from Enlightenment values and the rise of the european bourgeoisie — and then to colonial plunder and savagery, and Manifest Destiny, and almost countless genocides is open for discussion I guess. But there is a clear sense, I think, that at the very least the financialized epoch of advanced capital is connected to some version of disfiguring subjectivity. And that disfigurement includes the erasure of memory and history, and an intensification of interior rivalry and aggression. And when it is not that, it is the generalized eclipse of thinking. The narratives of western tradition are always resonant with rivalry. Cain and Abel, which is actually the first story in the Bible with people who were not created by God (Adam and Eve) is the ur Rivalry narrative. And that rivalry ends in murder. For there is always in stories of any lasting importance, a primal crime. And one senses, or feels perhaps, that such narratives are non digital. But more on that below.

Exposition building, Paris 1887. *Gallery of the Machines*.

The aesthetics of this ur-fascism is one with screen addictions — although it is not that simple. But the screen, as it comes to the public today, financed by major telecoms and information corporations, IS the machine dream of fascism. It is THIS screen, not screens. It is also fascism as a kind of virus. And the virus attached to a kind of Enlightenment value system that was remystifying society as an idea, and as material reality. And it was, it is now safe to say, a virus present at the dawn (or close to it) of the idea of progress. But how much this can be really linked with attention itself is more troubling…as questions go.

“The exhibitionary insistence on comprehensiveness resulted in an

astonishing accumulation of objects which seemed to privilege the eye over the mind and

to value things over ideas. Such an accumulation seemed to commentators to be

overwhelming and baffling rather than enlightening. In addition to their dazzling nature,

the Expositions also manifested the tendency of modern mass production to deceive the

eye and place a higher value on the superficial appearance of something than on its

inherent significance. The theme among critics of modernity was that this recourse to

illusion had the effect of producing an aesthetic completely devoid of historical meaning

and therefore “illegible.””

Elizabeth M. L. Gralton

“Thus, early in the 20th century, one could already see that the extension of media pathways as, in fact, the further ramification of the life-world by capital-logic. The communist revolutionary filmmakers marked capital’s encroachment on the visual as a site of struggle; Third Cinema (the cinema of decolonization), in Solanas’ and Getino’s manifesto, famously asserted that for the purposes of colonialism Hollywood was more effective than napalm (2000).”

Jonathan Beller

Will Ryman

The industrial revolution followed a logic of refining raw materials. And this process yields two things, one is refined product or extract and one is residue (per Raqs Media). The waste product was that which was not remembered. As Parikka quotes, there are no histories of residue. But this refining idea cuts across labor and social relationships, too. And today there is an accepted class of residue humanity. Extracting value is a narrative theme, in fact. And since this extract material, even when human, or a place, is valorized — while the shadow of this action of progress is designated waste material. The strip mined mountain is the performance, and the slag heap the residue. The minerals are the commodity, then. Extract. The evolution of alchemy. Benjamin saw in the detritus of bourgeois culture, and in ruins, something of the repressed waste product of the unconscious. The change from Benjamin’s arcades to post post modern digital capital has to do with, for lack of a better word, the fetishizing of the performance of attention. Mazzarato and others have discussed post Fordist labor, and the attention economy, but the thing that seems less investigated is the idea of self performance in attention labor. The universe of Google and Facebook et al is one in which attention is monetized, but that attention must register as such. At least for the subject. The self must perform the role of attentioner, so to speak. And this inches into many of the problems I associate with art critics like Bourriaud and Ranciere and Boris Groys; the focus, almost without their recognizing it, has shifted to that of the viewer. And the viewer, while he or she IS a performer of attention, is not the object of creative production. Bourriaud favors audience interaction, assuming something more political resides in things that disrupt passivity. Or individual passivity. But along with this assumed passivity is contemplation. And the loss of the contemplative is a much larger political loss in fact than tentative valorizing of institutional programming for the masses. But it is also the conflating of individual passivity with collective passivity, and the conflation of mobilizing with social movement. Still, the larger issue is this idea of *individual* — for it rarely is ever defined.

“Perhaps, the twentieth century shall one day

be reckoned as the period when capital went from being just one

form of mediation among many to being the ur-medium, cannibalizing

(and thus, iterating) nearly all other media from the cognitive,

to the cultural, to the psychological, to the visceral, to the televisual,

to the digital. Film, television, computing, and even architecture

become functional extensions of capitalism.”

Jonathan Beller

Barnett Newman, Jackson Pollock, and Tony Smith. Parsons Gallery April 51.

But I want to digress just slightly here for Beller wrote a fascinating essay on Filippino art and visuality, called Aquiring Eyes, and he mentions David Craven’s really very good essay on Abstract Expressionism. And it is worth noting that it was this post war epoch in the U.S. that had such enormous impact on aesthetic experience in the following decades. And Craven, of course, was (he died not so long ago, sadly) the major corrective to the lazy reflexive conflation of Ab Ex with cold war liberalism, McCarthyism, and CIA strategies. And obscuring the communist sensibilities of most of the New York school and the subaltern perspective and immigrant experience that was so embedded in their work. Craven pointedly insisted that Ab Ex was the anti monopoly capitalism gaze — the pluralistic and anarchic (and sexually charged) defeat of conformity and post war repressions. But back to Beller on this;

“As the massive literature on Pollock’s work testifies, his paintings—which for Greenberg were part of a movement that avoided content and aspired to create “something valid solely on its own terms, in the way nature itself is valid” —represented a tremendous crisis for semiotics and, one might well say, in the semiotic itself. The struggle to claim Pollock and Abstract Expressionism generally from and for various political quarters testifies less to the greatness of the work and more to the emergence of a new realm of visuality, the struggle for which characterizes the second half of the twentieth century. Thus, what appears is nothing less than a new arena of human expressivity and imagination, which then becomes contested semiotically, ideologically, and not least, economically.”

Gary Kuehn

The point here is that the ur Fascism that is expressed in the computational unconscious, and the attendant psychic code virus (which seems a riff off Burroughs and word virus, but also a language game that resonates with the jargon of Silicon Valley) is one who’s cunning is to snuff out all Dionysian arts and culture. And this where so much aesthetic confusion comes from. For later Beller quotes a Filippino critic who decries abstraction as elitist and bourgeois. There is the parallel western version of this, only worse, probably. And it the the confusion of ideology with art, and a hugely reductive narrative applied to the entirety of culture. But — to return to the idea of computation and computer consciousness, and societal aesthetics. The rise of the Nazi party did not immediately transform German social aesthetics — and in fact the early Nazi party officials took pains to appear modern and progressive. The famous Werkbund collective (out of which came many Bauhaus teachers including Gropius) initially tried to appease the Nazi party through shifts in focus from workers housing to middle class home designs. But also, as Paul Betts writes (in his excellent book The Authority of Everyday Objects)…

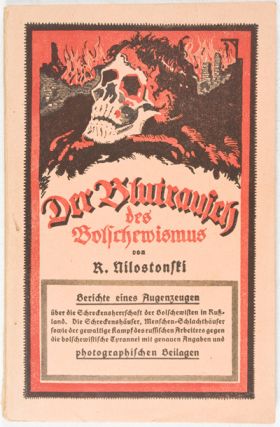

Der Blutrausch des Bolchewismus (anti semitic and anti bolshevik pamphlet, Germany 1925.)

“The sphere of industrial design is particularly illuminating here. It is

important to remember that the design object was radically transformed in the years immediately following the Depression. Much of this had to

do with the more general triumph of Neue Sachlichkeit, or “New Objectivity,”

in German culture. Numerous studies have chronicled the formal mutations in German painting, photography, and literature in the wake

of the Crash, particularly in the way that they jointly celebrated representational

precision and post-Expressionist subjective detachment, industrial ratio, and a flight from social relations. Less well known is that

German modern design also changed during the period. Generally speaking, it shed its lingering romanticism from the early 1920s in favor of a bold new machine aesthetic.”

As Betts says, chrome was the material of choice, and the vision was urban and reminiscent of much later Futurist work. Speed meant progress, and the vision was one of machine like rapidity that no mere human could hope to achieve. But it wasn’t just speed that seduced the public, it was the idea of removing doubt, or insecurity. And part of this formula coincided with mass production, simplicity, and shine. The shiny surface was associated with an impersonal hardness, a reflective coating that one could not wound. And all of this seamlessly met with mass production and cost effectiveness. A return on one’s investment.

Anicka Yi

And here is Betts again:

“For the triumph of modern design went hand in hand with the disappearance of its former reform idealism.

The once powerful political pathos of functionalism had given way

to a severe Neue Sachlichkeit divorced from any real social vision. Not

only did the Depression knock the wind out of the leftist dream of reconstituting

everything “from the spoon to the city” as a project of social

engineering, the interwar linkage of modern design with social justice

had collapsed as well. Modern design goods were now recast as new

Depression Era markers of coveted cultural capital and social elitism.

There was of course a strong element of elitism in interwar modern design

all along, but it was usually connected to a larger program of social

betterment for all classes. The social(ist) dimension abruptly dropped out

of the picture. Ironically, it was the crisis of economic liberalism that

brought about the “liberalization” (in this case, the social deradicalization)

of modern design.”

Trevor Paglen, photography (NSA/GCHQ, Bude, Cornwall, 2014)

Commodified machine dream was the fascist aesthetic engine that drove out the socialist sensibility of Bauhaus teachers and artists. There was, and there remains, a quality of self loathing embedded in ruling class attachments to art that is anti human (Robert Wilson, Marina Abramovic in the prestige realm — and CGI cartoon blockbusters on the entertainment level). What is fascinating, I think, looking at the Nazi trajectory, culturally speaking, was that they instinctively embraced commodified forms and aesthetics. And looked to design goods as emblems of Nazi progressivism. Side by side with this was the removal of kitsch — in the terms of National Socialism this meant clutter and bric and brac (from the degenerate past). There was a careful extracting of clean modern lines and anti septic shininess from out of industrialism overall. But also the removal of the wrong kind of sentimentality. For the Nazis did, later, become hugely sentimental, of course. The aesthetics of eugenics — the iron cross and eagle, the Aryan blond children frolicking on grassy hills, etc. But in those first years, the eradication of impurity included village bonfires made up of household items no longer deemed modern and progressive. Future looking was mandatory. And the result, with Werkbund help, were household designs in keeping, generally, with early modernism. The paradox then is that Nazi aesthetics and cultural policy was directed at cleansing — cleaning out Weimar kitsch, commercial appropriation of national symbols — while still carefully building a blood and soil mythology. The early National Socialist design schemes were actually not unlike Bauhaus design (albeit already rounder and softer) and it was not until later that degenerate art came to include anything, essentially, not officially Aryan and volkish. In other words the Nazis used their ideological enemies (per Betts) to further their interests. Much as the CIA tried to appropriate abstract art to further their anti communist hysteria.

It is also notable that the Nazi design of household objects focused on simple and honest, a kind of romanticizing of primitivism one finds exactly in Heidegger.

Barnett Newman

The post post modern computational aesthetic mirrors much of this, in fact. The removal of trash (clean your cache) is constantly repeated, and this theme of extraction looms over this, I think. And that means residue is expected and a part of the plan. And residue, or waste, is then also hyped as a societal problem. The overcrowding mantra is aligned with this. And while, say, plastic bags ARE a problem, the implications here are directed more at waste humans. The global poor are the waste items of neo liberal capitalism. And while expected, are also what ruins the aesthetics of clean emotionless shiny blankness. Generalized autism, as Debord put it. And that clean empty imagery is equated with freedom and individuality in the West. And again, looking at National Socialism, the Nazi Reichsautobahn project was principally a propaganda tool, really. The images of empty highways was circulated throughout Nazi propaganda pamphlets and in newspapers. The autobahn suggested a future of unlimited travel and movement. The American highway system has always, as well, figured in American mythology as independence. One must always be moving. As Jim Harrison once said, driving open empty roads was really about having nowhere to actually go — but then he added, you can’t hit a moving target. And this again is familiar from Marinetti and Italian fascism. War as the only hygiene. And Marinetti also loved the automobile. This idea of forward momentum seems always of a piece with both classical fascist aesthetics, and also simply capitalism. The financialized version of Capitalism has morphed this forward drive into something of a different space. And Betts, actually, speaks a lot about the Nazi emphasis on *German space*. For the U.S. the idea of wide open spaces was the gunfighter pastoral of the violent American — the vigilante and Indian killer. The scalp hunter and slaver. Always in wide open spaces. But financial capital makes wide open spaces into something borrowed from NASA. The space race was against communism, after all. And the mutilated sexuality of rocket launches and a race to nowhere became something akin to cyber space I suspect. And this is partly why Trevor Paglen’s photographs are so disturbing. For they capture the anti human quality of a technology that has no role in people’s lives, but promises endlessly to repair those lives anyway.

Anselm Kiefer

So, where the Nazi’s aestheticized politics, they did so more by mechanizing life, or the idea of life, than really any of the volkish mythology. Albert Speer’s creations foreshadowed brutalism, but also hinted at something disturbingly anonymous about space. Gothic cathedrals, again in one way, did the same by handing the space to God, and by the intimidation of scale. The human is always, eventually, in authoritarian systems, sacrificed for the machine. Traverso saw it in WW1, in the gas masked soldiers, in death from above. The first industrially planned war. The Weimar year artists from both left and right borrowed from this prescient feeling of losing oneself. German cinema — the UFA studio material that preceded National Socialism produced a number of examples of human loss, of mechanized man (Metropolis being the most famous) but it was also a fear of the terror within. The psychoanalytic sensibility of those first generation radical associates of Freud — sensing in the inner disfigurement and the Death Drive. For the death drive feels closely linked to this computational unconscious. Cyber space is the new empty prairies of the mythic West. I find it no accident that so many seminal American painters and artists of the 20th century came from prairie states, or the empty West. The greatest of American painters all found something of the truth of the terror lurking in that space, even if not born there, they often, invariably, found their way. Barnett Newman, Agnes Martin, Still, George Ault, Rothko, Pollack, and Motherwell. But that sense of something errant in the wide open, the disenchantment of this mythology, was crucial in one way or another to all of them.

Slawomir Elsner

Remember, too, that Nazi and fascist mythology overall, insists on the non human quality of its enemies (Jew, Bolshevik, African, Arab, etc). But it is again, a specific sort of inhumanity — it is disease or the threat of seduction. It is insect life, because really, deeper down the fascist aesthetic is really all about the non human. And that is partly what is so perceptive in Beller’s idea of this computational unconscious. The Ur-fascism. There is the evolution of fascist aesthetics into post war American conformity. The compulsive nostalgia for the 50s and 60s in Hollywood today (and even the 70s and 80s) has several causes, but the most telling is perhaps the desire for cleanliness. And here is the racial aspect to the interior terror of fascist culture. The white Ozzie & Harriet world was recouped by Speilberg and John Landis and other directors, as suburbia. A white suburbia where dark skin was allowed for domestic help or token comedy asides. The gender aspect is obvious here as well, for this was the era of Betty Crocker. And in a sense Mad Men was really about this more than anything else. The birth of marketing and the re-experiencing of gender oppression. How fun.

Richard Texier (1955)

“The same was true for the relationship between subject and object. As noted, there was great breast-beating in the ’50s about consumerism’s

sinister power to undermine subjectivity through standardization and manipulation, in which “personality” became a shrewd marketing stratagem

in the hands of postwar merchants and advertising agents. But if subjects were being turned into market objects, as many contended, the

reverse was also true,{ }. This is the often overlooked significance of the introduction of self-service stores and the rise of new commodity packaging in the ’50s. Michael Wildt is surely right in interpreting these innovations as ushering in a new aestheticization of everyday life, one in which visual impression replaced tactile sensations as the basis for commodity judgment. But it also meant that the object now took on distinctly subjective qualities. The end of the seller’s physical mediation of the good and the subsequent rise of packaging as advertising meant that the consumer good now sold itself. As Zahn noted in his Sociology of Prosperity, the object now “reports in and introduces itself, speaks for itself and sells itself. Packaging thus lends the object a subjective character.”

Paul Betts

Warhol painting car for “Happneing”, 1979.

The post post modern fascist aesthetic is one of erasure and residue. Of surveillance and the eroticizing of surveillance. The computational is a form of aestheticizing privacy as well. Behind all this is the superior form of the machine. Of technique, too. Skilled with motorcycle or bungi jumping. The skills needed for computer gaming. All of it is eroticizing alienation, of sexualizing loneliness in a sense. As community disappears the compensatory tectonic shift is toward isolation. And the only communal activity is bickering on facebook or twitter. Technique substitutes for both emotional connectivity, and on a social level it works in conjunction with this new imaginary of neutral privacy.

“Modernity is characterized by a highly rationalized industrial production, complex technological infrastructures, and a substantial degree of bureaucratized administrative and service activity…”

Detlev Peukert

Peukert was writing about the Nazi era, and saw in household design and an encouragement into privacy as the front edges of later cults of individualism. The U.S. version of this followed a similar path, only one with a more lurid style, and with a palpable addiction toward violence. The current prison strike taking place this week (and one should follow and support the Free Alabama Movement and the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee (IWOC)!) reflects labor attitudes that have existed in U.S. culture since colonial times. From strike breaking by Pinkerton agents to railroad goons, the authoritarian nature of American society has always favored physical violence as a first option and not a last option. Physical technique begins, for American culture, with physical power and coercion. The final point here here, for there is a lot more to say next posting, is that aesthetic practice is both cause and effect. But that perhaps layered beneath everything is a kind of computational impulse that is forward looking and atomizing. And that it has ratcheted up a white ideal that demands racism is gone, imperialism doesn’t exist, and class a phantasm. Hollywood has now, for the last decade, recycled zombie stories and romantic comedies (and now both together) along with ironic historical revisionist narratives of white goodness. And this cannot, really, be separated from the white left who, for example, demonize Assad because their tendency is toward discipling the dark skinned and poor. Nor from the cracker white and angry unemployed who follow Trump and are seething with racist rage. Or the complacent bourgeoisie who instinctively, also, look to retain the status quo — a more polite distanced racism and imperialism. All of these groups are white knuckling and in a cold sweat. They are desperate. For the illusion of maintenance is unravelling. There is more residue than there is extract, now. And I suspect the narrative themes of Hollywood today are metaphors for this reality. From zombies to plagues to viral outbreaks; it is the system failure for residue control. For refuse management. And there is ever more fear that it is failing.

“IBM developed the punch card to cross-reference German populations for Nazis looking

for Jews, gypsies and homosexuals during the Holocaust and this development was a

precursor to modern computing.”

Jonathan Beller

Speak Your Mind