Mikhail V. Matyushhin

“Let them be ashamed and confounded together that seek after my soul to destroy it; let them be driven backward and put to shame that wish me evil.

Let them be desolate as a reward for their shame that say unto me, Aha, aha.”

Psalm 40, 14-15

King James translation.

“The growing centrality of organized science to the modern

industrial state, largely unrecognized until the First World War, made

the scientist ‘as much a salaried official as the average civil servant and

business executive’. As such, the scientist, like any worker, must

choose between job security, personal fulfillment and more lucrative, but

riskier, opportunities: ‘no longer, if ever he was, a free agent’, the scientist’s

‘real liberty … is effectively limited, by his needs of livelihood,

to actions which are tolerated by his paymasters’, often resulting

in servile conformism.”

J.D. Bernal

“No real and complete memory every appears in our dreams as it appears in our waking state. Our dreams are composed of fragments of

memory too mutilated and mixed up with others to allow us to recognize them.”

Maurice Halbwachs

It is often curious what memories survive in our conscious minds, especially from childhood. I went to the movies with my father a lot when I was a kid. I loved movies as I was an only child. My father never took me to children’s films, mostly because neither of us liked them. Anyway, I remember this one film that came out in 1958 in the U.S. And it disturbed me for years. Only recently did I discover again what it was, as I had long since forgotten it. The title was Quartermass 2, and it was a Hammer sci fi film from the U.K., and part of a series of films featuring the character Professor Quartermass. I didn’t have many clear memories of this film, except for the image of the man covered in a black tar like substance, a substance burning him, and his staggering down the stairs of a large water tank to finally fall and die. Now, looking back, it is interesting to see the implications of this image, and the trace elements of collective horror that it contains. And before one objects, this was for me an indelible image, a memory that disturbed the seven year old version of myself for weeks if not months.

Quartermass 2 (Val Guest, dr. Nigel Keane screenplay). 1958.

Val Guest, the director, was actually a very talented if minor figure in British post WW cinema. Here from his obit in The Telegraph:

“Guest directed two low-budget British thrillers which were well-received by the critics, and regarded in some quarters as being among the best science-fiction films ever made.

The Quatermass Experiment (1955) gave Hammer Films its first box-office hit and set it on its future course; while President Kennedy was so taken with The Day the Earth Caught Fire (1961) that he screened it for 200 foreign correspondents in Washington.

Guest was not a science-fiction fan (he had made his name directing comedies), so he almost turned down the chance to adapt Nigel Kneale’s six-part television series The Quatermass Experiment for the cinema..”

Guest did take the job and followed it up with Quartermass 2, Enemy From Space. Now, I think what I found disturbing about the film was the sense of paranoia that pervaded the atmosphere. This was the cold war and it was the Atomic Age, and the NASA age, and for America it was the dawn of astronaut mythology, and the space race. But in the U.K. the atmosphere was darker. The country was still recovering from the trauma of the war. And this is what one feels in these Hammer produced sci fi films. All of them pessimistic and anxious.

Quartermass 2 (Val Guest, dr.) 1958.

But the interesting and perhaps inexplicable factor for me, at the time, as a seven year old, was the burning man, tarred really, coming down the stairs. This was a collective unconscious responding, it was a figure of lynching, a *black* burning figure, a victim — and it was also the impersonality of the landscape that haunted me. The same anonymous and anodyne quality that I found a bit later in the American TV series The Outer Limits. This was also the science migrated world of industrial finance; metal filing cabinets and anonymous office workers in cubicles, only in this case, and others like it, the office prole became the science worker. The grey men in lab coats and heavy black frame glasses. It was the last gasp of clean cut white male heroism, too.

There is an interesting riddle in the heart of this, if riddle is even the right word. That the default symbol of horror should be a tarred man, an *alien*, burning, and surrounded by a white world of anonymity and secrecy is probably not accidental. It has both a quality of the prophetic about it, and also recycles one of deepest psychic and historical horrors of the U.S. and its self created mythology. And is an aspect of the importance of cultural production.

Photographer unknown.

There are two branches of implication here. One has to do with instrumental thinking in general, and the second has to with the externalization of trauma, the ugliness of the contemporary world, and then also the complicity of many — certainly the bourgeoisie — with white supremacy and the hierarchical class system of the West. All the science fiction film (and TV) that came out of both Hollywood and the U.K. in the 50s was valorizing science as the savior of civilization. The heroic work of dedicated guys in lab coats. Now that this arrived on the heels of Hiroshima makes perfect sense because it was an overdetermined allegory — both guilt and horror, and triumph and Utopian dream. The Utopian was always beset by nightmares, however.

“The dream of industrial abundance has enabled the construction of global systems that exploit both human labor and natural environments. The dream of culture for the masses has created a panoply of phantasmagoric effects that aestheticize the violence of modernity and anaesthetize its victims.”

Susan Buck-Morss

The background for the cultural representations of science borrowed heavily from an imaginary that implied global obedience. This went back to Manifest Destiny and The Monroe Doctrine and the implied presence of police power and authority. Science was intimately intwined with coercive institutional power.

Jan Sluyters

The Monroe Doctrine has really never gone away, as a cultural principle. Kosovo, and whatever happens in the middle east over the next decade is all part of viewing the periphery as immature and in need of training. Much as unruly teenagers need to be paternalistically disciplined. This was white patriarchy, and it was the colonial logic that segued perfectly with U.S. foreign policy after WW2. The various art movements of mid century, mostly in Europe (and really dating back without much interruption to the late 19th century) reflected a kind of abhorrence of this new conformist science. The anti communism of U.S. policy makers was driven not just by a desire to retain and maximize profit, but by a sense of necessary disciplining of the developing world, of the colonies and former colonies. But this sense of entitlement was always in bad faith — and this is partly the source of these collective returning nightmares of Empire.

Susan Buck-Morss points out Kissinger’s famous comment on Chile after electing Allende…“I don’t see why we need stand by and watch a country go communist due to the irresponsibility of its own people.” Chile was the rebellious teenager in need of a firm hand. But really, this was the nightmare of American power brokers, of the ruling class. A country with the temerity to suggest the people of this country were sovereign and autonomous. As Buck-Morss says…..“This special kind of imperialism that insists it is no imperialism cannot continue to exist if the political enemy ceases to exist.” There was a nightmare, but there was a deeper need to HAVE those nightmares.

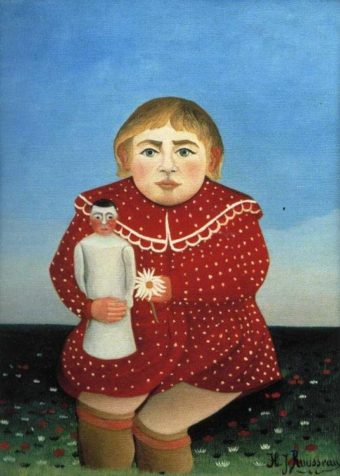

Henri Rousseau

Now, this returns again to how individual memories are altered over time. That movie I saw in 1958 with my father no longer exists. And if I were to watch it again, I would come no closer to my state of mind at the time of first viewing. And probably I would end up further removed from the experience. But what interests me here is how a collective memory, for lack of a better term, is expressed as part of the societal imaginary today.

“What makes recent memories hang together is not that they are contiguous

in time: it is rather that they are part of a totality of thoughts

common to a group, the group of people with whom we have a relation

at this moment, or with whom we have had a relation on the

preceding day or days. To recall them it is hence sufficient that we place

ourselves in the perspective of this group, that we adopt its interests

and follow the slant of its reflections. Exactly the same process occurs

when we attempt to localize older memories. We have to place them

within a totality of memories common to other groups, groups that

are narrower and more lasting, such as our family. To call to mind this

totality it is again sufficient that we adopt the attitude common to

members of this group, that we pay attention to the memories which

are always in the foreground of its way of thought. Based on such

memories, the family group is accustomed to retrieving or reconstructing

all its other memories following a logic of its own.”

Maurice Halbwachs

Mass culture, though, per Halbwachs comment above, is the new family for the post modern society. People remember movies and TV as if they were part of family folklore.

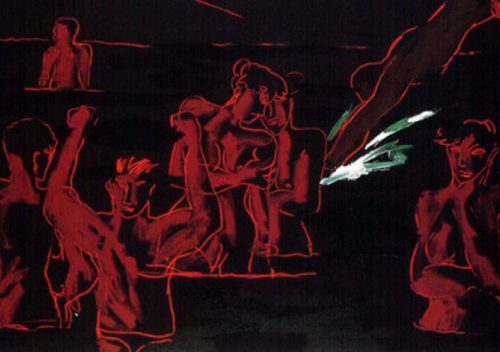

Bruce McClean

I have noticed that people will either remember the past using mass cultural items as signposts (oh that was when Star Wars was released) or they simply insert scenes or dialogue or images of some sort, from film and TV, into their own memories (a bit like Reagan did, which may account for people seeing him as ‘the Great Communicator’). And on a collective level, these insertions bleed into the dreams and nightmares of others as secondary dream material.

Paul Ricoeur, in his book Memory, History, Forgetting, touches on the problems of how to speak about collective memories. And he points to a significant essay, and lesser known, of Freud’s, from 1924.

“…titled, “Remembering, Repeating, and Working-Through.”

Note right away that the German title contains only verbs, stressing the fact that these are three processes belonging to the play of psychical forces with

which the psychoanalyst “works.” The starting point for Freud’s reflection lies in identifying the main obstacle encountered by the work of interpretation (Deutungsarbeit) along the path of recalling traumatic memories. This obstacle, attributed to “resistances

due to repression” (Verdmnjjunjjswiderstdnde), is designated by the term “compulsion to repeat” (Wiederholunjjszwan/j); it is characterized among other things by a tendency’ to act out (Agieren), which Freud says is substituted for the memory. The patient “reproduces it not as a memory but as an action; he repeats it, without, of course, knowing that he is repeating it”

Silvio Berlusconi, singing on cruise ship, 1960s. Photographer unknown.

This is obsession, or something very close to it. But the important point here is that memories are recreated anew, but recreated by active insertions. There is some kind of durational necessity involved, psychically. Also, Ricoeur notes that the distinction (per Freud) between melancholia and mourning is the absence of individual self regard in mourning. It is a bit more complex than that, but the germane point is that in mourning the first process put in motion is a kind of reality testing (is the loved one really gone, really dead?). The process of testing can be prolonged for quite a while, and this is due, in part, to the resistance of the libido to the dictates of reality. In mourning the world is diminished, somehow. In melancholia, the ego is diminished. The ego is accused, questioned, interrogated, and these actions mask, partly anyway, or deflect, the accusations toward the missing person. There is a trajectory here from such self debasement, hiding or masking the debasing of the love object, to original narcissism, and to the sadism inherent in that narcissism.

“When we say, “In our family we have long life spans,” or “we are proud,” or “we do not

strive to get rich,” we speak of a physical or moral quality which is

supposed to be inherent in the group, and which passes from the group

to its members. Sometimes it is the place or the region from which the

family originated or it is the characteristic of this or that family member

that becomes the more or less mysterious symbol for the common

ground from which the family members acquire their distinctive traits.

In any case, the various elements of this type that are retained from the

past provide a framework for family memory, which it tries to preserve

intact, and which, so to speak, is the traditional armor of the family. “

Maurice Halbwachs

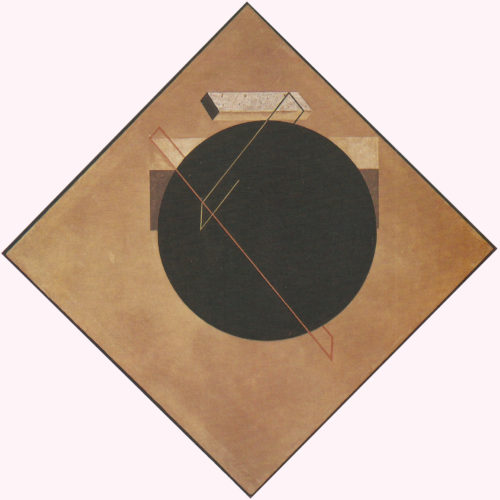

El Lissitzky

Now, the post modern notion of group, or of belonging, is riddled not with religious traditions or ceremonies, or even with much sense of *where*, but more with mass cultural product. Melancholy is the cancellation of your favorite TV show. In a sense, this is reified memory recall. Halbwachs, in his much neglected book Collective Memory, notes that as time passes these signature familial memories attract more detail and reality, not less. They are not simplified over time, but increasingly over-determined. In this process there are numerous substitutions, in other words, if we remember a trip with our Uncle it may be that an image of a bridge that was seen becomes part of a memory narrative not including the Uncle but someone else. Or, increasingly I think, with figures out of mass culture. Walter White is inserted on that bridge. Or dialogue from a favorite show. And the point is that such images or narrative fragments take on ideological resonance. The kitsch dialogue from some movie is ceremonialized as part of a process of manufactured memory, but memory that is ticketed for collectivity. The collective memory idea is really just the need to fill in for absent consequential material.

There is another branch to popular notions of memory; and that is the command to remember. The command or injunction to remember means to remember what we tell you to remember. And in an age of such virulent propaganda (look at Hill & Knowlton, PURPOSE, and the various other official corporate entities of spin) it is important to see how collective dreams are being both shaped and excised.

Suh Seok

Now, as something of a side bar, but still a highly relevant side bar, Dominic Losurdo writes of the new revisionism found in historians like Ernst Nolte (though he is but one, and an early one, of an increasing number)…

“In today’s historical revisionism, there is no reference to Maurras and Ford: it is a question of exclusively indicting the revolutionary tradition from 1789 to 1917. In tracing the history of conspiracy theory, Furet establishes a dizzying line of continuity between the French Revolution and Nazism: the ‘aristocrats’ and class enemies sniffed out first by the Jacobins, and then by the Bolsheviks, become the Jews who were the object of Hitler’s paranoia. Not a word is spent by the French historian on his esteemed Burke, who was among the first (as we shall see) to detect a Jewish hand in the unprecedented events across the Channel. Little or no attention is paid to the extraordinary vitality of the myth of the Jewish conspiracy supposedly underlying revolutionary upheavals. In the course of the struggle against the October Revolution, this myth celebrated its triumph not only in Germany, but throughout the West. The initial head of the crusade against the Judeo- Bolshevik conspiracy was Henry Ford, the American automobile magnate. To foil it, he founded a paper with a large print run, the Dearborn Independent. The articles published in it were collected in 1920 in a volume entitled The International Jew, which immediately became a reference point for international anti-Semitism, to the extent that it ‘probably did more than any other work to make the Protocols world-famous’. Much later, front-rank Nazi leaders like von Schirach and even Himmler claimed to have been inspired by Ford or to have started out from him. In particular, the second recalls having understood ‘the Jewish danger’ only after reading Ford’s book: for Nazis it came as a ‘revelation’. Reading of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion followed: ‘These two books indicated the road to follow to liberate humanity from the affliction of the greatest enemy of all time, the Jewish international.’ According to Himmler, along with the Protocols, Ford’s book played a ‘decisive’ (ausschlaggebend) role in the Führer’s formation, as well as his own.What is certain is that The International Jew continued to be published with great fanfare in the Third Reich, with prefaces underlining the decisive historical merit of the American industrialist (for having shed light on the ‘Jewish question’) and disclosing a kind of direct line from Henry Ford to Adolf Hitler!”

Robert Gendler, space photography.

The formation of memory that I want to stay focused on, is linked to this modern notion of technology and science. There is something in how it is discussed that keeps nagging at me. Much post modern thought addresses, officially, the role of digital culture, of advanced electronic media, but most of it feels fungible. I can think of maybe only Jonathan Beller as having added something of substance and originality. And Beller was echoing Debord in some respects, but looking to both contemporize and modify. The spectacle is both, for Beller and Debord, itself *capital*, and in another sense it is the colonizing force of our collective dreams and nightmares. By which I mean that in some register the mass electronic and technological apparatus (and apparatuses) penetrate our unconscious which serves as both passive receptacle and as a generator of an ever changing enclosure. And this is the slippery part of this. This psychic enclosure, it not strictly speaking only psychic. It is expressed now in images, familiar ones that have already been processed, and serves as at least a part of the daily background of material lives, as well as a good part of how we *feel*. It is also, per Beller and Debord, and maybe Baudrillard, a form of Capital. Our attention is monetized. And within this monetizing procedure, this activity that generates more monetized attention, there is also a surplus or spillage of unconscious material.

Now, let me quote Beller, in a long-ish quote from an interview he gave a couple years back…

“Every discursive instance has a politics to it. There are no isolated spaces that are somehow separated from global production – for us, at least. The whole Virno idea of capital capturing our cognitive-linguistic capacities, brilliantly articulated in A Grammar of the Multitude, shows that the discursive ground itself has been captured by capitalist production, that we have become very good speakers for capital and that, no matter what else we do, our very negotiation of our own survival is in part complicit with the system of accumulation that perpetuates hierarchical society. To me an awareness, an abiding awareness, of this condition mandates a kind of politics that I call “the politics of the utterance.” It is a kind of haunting by the unrepresented and, under current conditions, perhaps unrepresentable which (who) demands something from us. These agents are not only extrinsic (as in beyond “our” borders) but also intrinsic (part of the very constitution of consciousness). I would say that one thing that is demanded is a recognition that our own signifying practice at the most fundamental level depends upon the history of dispossession and the logic of it and that whatever we say, will say or might say owes something to the invisibility and the foreclosure of the representation of the exploited global poor past and present.”

Stranger at The Lake (2013) Alain Guiraudie, dr.

This is part of the collective memory we cannot get outside. Which is what I’m trying to get at with the idea of an ever shifting enclosure. Constitutive of consciousness, but also of memory — and because attention is now monetized, the entire sense of personal corporeal self is given over more than ever to acute anxiety and absence. The collective memory is always, then, today, a memory of what isn’t and can’t be there. It begins to feel a bit like a Dr. Mabuse sequel — and this is the problem. For the backdrop for reality is a rationality that doesn’t quite exist. The *science* of this post modern imaginary is a kitsch science. And it exists outside class and race, and certainly outside history. This is just appearance and image, representation, and not material reality — whatever that is. This is only the revisionist story of US society. And, of course, only one aspect of that revisionist story. Whole chunks of actual history remains redacted in the official master narrative (slavery, the actual conditions of slaves, the genocide of Native Americans, the real horrors of Puritanism, etc). And this works well with the discouragement of seriousness and the encouragement of infantile entertainments.

The disenchanted contemporary world is one in which both literal and figurative shadows are removed. Jonathan Crary noted that when he said it is so… “in its eradication of shadows and obscurity and of alternative temporalities.” A world identical to itself. Except it’s illusion, of course. Now, Crary shortly after this comment, introduces a discussion of Tarkovsky’s Solaris (1972), which segues quite well with this topic of kitsch science. Tarkovsky was answering Kubrick’s 2001 A Space Odyssey. And these were both films that seemed to imply a rejection of what Crary calls *exposure*. But they were also indicating the delusional side of space exploration overall. The *colonizing* of space. For that colonial vision of the world completes the backdrop of kitsch science. And it is never not an integral part of Western Utopian dreaming. New worlds to conquer. The more existential and ontological questions of the Universe were just put aside, since they contributed little to consumer growth, and instead NASA became just another industry — which of course is all it ever really was anyway.

Maurice Halbwachs

The whole topic of collective memory is inseparable, finally, from questions of awareness. And that in turn links to how we dream and to sleep and to the unconscious. The mid 20th century was one in which artworks began to, instinctively, coalesce around this question of waking, or awareness, and of sleepwalking. These themes permeate writers and painters of mid century and earlier, even, for the slide toward disenchantment was clearly picking up speed. And it is Kafka, perhaps more than any other writer, who sensed the coming erasure of memory. In The Castle there is only, essentially, waiting. And this was taken further by Beckett. And by, in another way, Genet. But in film, the capturing of this enigmatic and perhaps unrecognized guilt or shame, is expressed (as noted last time, I believe) by stealth. And maybe it is in the stealth necessity that an expression of collective nightmare is better captured. Quartermass 2 features a tarred black man — call him alien, it doesn’t matter — who cannot be gotten rid of. He cannot be unseen. He is the dream that cannot be forgotten. For he is not a dream but a memory. And I think one of the more disturbing aspects of Sirk’s films is that everything feels like overdetermined nightmare images that nobody will speak about. Bunuel too, in his later films, creates this odd dislocation. And one might apply this interpretative trope to many later films, and find a kind of insight. Stranger at The Lake is a far more meaningful film than, say, anything by the Cohn Brothers for exactly this reason. The Cohn’s films are there to obscure the dream somehow, or to artistically tip toe, the better not to wake the viewer. The Alain Guiraudie film does nothing quite so impressively as make us aware of being enclosed. The characters roam the lakeside vacation area cruising for sexual encounters, except really, they aimlessly search for the laws of their lack of freedom.

“The first decades of this century stand under the sign of technology. Good! But that only means something to those who know that they proceed under the sign of the resurgence of ritual and cultic traditions as well.”

Walter Benjamin (1928)

Roman Opalka

The lie of scientific neutrality casts a long shadow over the entire 20th century. From WW1 to Hiroshima and Vietnam.

“In this intensely polemical situation, which opposes a younger tradition

of objectivity to the ancient tradition of reflexivity, individual memory and

collective memory are placed in a position of rivalry. However, they do not

oppose one another on the same plane, but occupy universes of discourse

that have become estranged from each other.”

Paul Ricoeur

So there is a kind of metaphor involved in how we forget. The rivalry embedded in our mental development, in our very definitions of self, is expressed metaphorically as an opposition between individual memory and collective memory. But this goes right back to Freud, again. And to Halbwachs…

“…a person remembers only by situating himself

within the viewpoint of one or several groups and one or several currents of

collective thought”

Maurice Halbwachs

Diego Rivera (detail)

The American emphasis (of pathological intensity) on individuality has made forgetting the primary mental activity of the entire culture. And this idea of collective remembering is found in de Certeau and Bachelard, too. And so, looking at childhood memories, it is easier to see the ways in which children associate places (linked to family) with events remembered — in a way adults have been conditioned to disregard. These frameworks (Halbwachs) allow the child multiple temporalities. The very thing Crary noted was being obliterated in post modern culture. The kitsch science is one of a single objective temporal plane. The social setting of events, as experienced, is erased, at least partially, and thus it makes it much easier to forget. And politically this is evident in the continuous amnesia regarding both policy and event. The candidates in electoral theatre only exist in the *now*. There is a Kantian argument lurking in this somewhere. Our consciousness of self remains singular, in the end. For Ricoeur, and for Halbwachs too, the primary deficit in the contemporary psyche is the loss of awareness of the social framework of consciousness.

“When social influences are in opposition to one another and when

this opposition itself is unperceived, we convince ourselves that our act is

independent of all these influences because it is exclusively dependent on no

one of them…”.

Paul Ricoeur

Edgar Martins, photography.

I might make the argument that in an era of forgetting it is film that has taken on the role of a memory machine. *We* remember through the collective of cinematic art. Directors such as Ozu and Sirk, Mizoguchi and Straub are the primary priests of memory. For it is their insistence on the fragility of our sense of self. Ricoeur not surprisingly discusses Jean Pierre Vernant and Marcel Detienne, whose work on ancient Greece so impacted that field. And it was Vernant who saw the shifts from the 8th to the 4th century in Greece as seminal in how contemporary ideas of causality, imagination, memory and agency were first formed. And for both, the Tragic drama of the 4th century marked both the recapitulation of myth and the dawn of rationality. Of a particular form of rationality anyway. But it is de Certeau who grasped a perhaps even more significant aspect of remembering in a short essay on Freud’s writing of Moses and Monotheism. For it is here that de Certeau touches on an idea I have tried to express over the last couple years and that is how we re-narrate what we both read and write, and view. It is, as Ricoeur says, the search for the *place* of doing history. Freud’s writing a *novel* of history, essentially, but as a history among other histories, that provides the frame for further questions.

And there is a sort of post script to these reflections, and that is the work of Francis Yates. For Yates writings on the esoteric Hermetic cults, on Giordano Bruno, and later Robert Fludd and the Globe Theatre, who is also finding relevance in the art of theatre in relation to contemporary amnesia.

“It has been the purpose of this book to show the place of the art of memory at the great nerve centres of the European tradition. In the Middle Ages it was central, with its theory formulated by the scholastics and its practice connected with mediaeval imagery in art and architecture as a whole and with great literary monuments such as Dante’s Divine Comedy. At the Renaissance its importance dwindled in the purely humanist tradition but grew to vast proportions in the Hermetic tradition. Now that we are already in the seventeenth century in the course of our history will it finally disappear, or survive only marginally and not at the centre? Robert Fludd is a last outpost of the full Renaissance Hermetic tradition. He is in conflict with representatives of the new scientific movement, with Kepler and Mersenne. Is his Hermetic memory system, based on the Shakespearean Globe Theatre, also a last outpost of the art of memory itself, a signal that the ancient art of Simonides is about to be put aside as an anachronism in the seventeenth century advance?”

Francis Yates

Carol Bove

When Benjamin said the tragic form was one of revealing, an act of making known something otherwise hidden, he was touching on questions of memory. And memory itself is laced with symbols and metaphors of light and darkness. And of place. My memory of a minor British science fiction film from the 50s was really about a memory of my father. But that memory is not possible without a collective repressed memory of lynchings and oppression and race. My family mythology is not isolated from historical social trauma. In such a context then, all theatre is a memory art. And all film is an art of amnesia. And neither is more important, finally, but it is telling that so much film works so hard under a system of advanced Capital, to nullify its own meaning.

Theatre has such importance because even bad theatre must be rehearsed and the residue of memorized speech looms spectrally over the ritual of performance. It is not surprising that the bourgeois theatre of contemporary America is one which validates that which is least theatrical — that which is most like a TV show or film. Or advertisement. And as a second footnote of sorts, the recent revelations of Marina Abramovic’s diaries (now removed from the soon to be published version) included naked colonial racist remarks on Australia’s indigenous people. What a surprise. The empty and fraudulent anti humanism of Abramovic was obvious to anyone who really bothered to look. But most don’t look. And that defect, that loss of looking, is why they can’t remember anything. They don’t remember Milosevic was pilloried as a monster and the Serbs the new Nazis. That trope now rejected lives on in cultural production because nobody making those products can remember what happened a decade back. That is unless they access a TV show from that period. And so the fiction lives on.

Ugetsu (1953) Kenji Mizoguchi, dr.

“Historiography tends to prove that the site of its production can encompass the past: it is an odd procedure that

posits death, a breakage everywhere reiterated in discourse, and that yet denies

loss by appropriating to the present the privilege of recapitulating the past as a

form of knowledge. A labor of death and a labor against death.”

Micheal de Certeau

When de Certeau saw in Freud’s investigation of a fictional Moses something of revisionist history, how a fiction erased the real, it was the real link to the later culture of total fiction. Once the social is erased from memory, the social contemporary starts to unravel. Our personal histories become fictions. Layered over this is the primary narcissism of a culture desperately insisting on this fictional self, consumer and lemming, who because of this narcissistic personality is incapable of an imaginary that extends beyond their own reflection as presented in mass culture.

Speak Your Mind