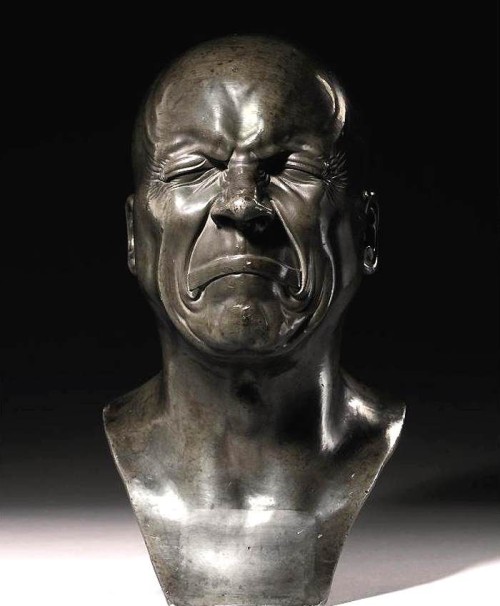

Franz Xavier Messerschmidt

“Death is especially awkward for modern intellectuals who are likely to find themselves swept over by traditions they fought and measured themselves against.”

Michael Taussig

“The barbarism of the present was already germinating in that period, whose concept of beauty showed the same devotion to the licked-clean which the carnivore displays toward his prey. With the advent of National Socialism, a bright light is cast on the second half of the nineteenth century.”

Walter Benjamin

“Imperialism gripped the world as totality – a total market and completely exploitable productive source. Imperialism was unifying the world through trade routes and commodity exchange or plunder.”

Esther Leslie

This has been a particularly disturbing last eight or ten weeks. One senses a collective rupture in the psychic membrane that covers bourgeois society like a cheap condum. The first and primary symptom are the reactions to the Trump and Hillary electoral theatre. But almost as if ordained by cosmic correlation and parallelism, the Brexist vote comes in with an unexpected *leave* verdict. And I think the public response, the social response to both of these narratives has been one of near psychosis. Many many people I know, and many of whom I like, and many who I genuinely respect and even admire, have seemed to have come unhinged. There is an obvious layer of white affluent condescension regarding Brexit; how dare the multitudes not vote as Empire wished them to vote. My first response to that was why do these white liberal clerks to power *want* a continuation of the EU? As if suddenly we are to believe they care about racism and xenophobia? But the second storyline here is related to my last post on Duende, and the Orlando shootings. And on the public outcry of faux grief. And Andrew Wimmer comes along with a very good piece here: http://www.counterpunch.org/2016/07/01/killer-grief/

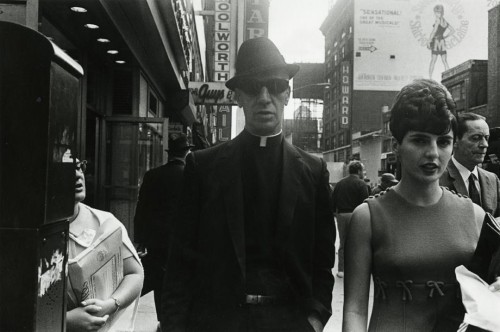

Paul McDonough, photography (Priest with dark glasses, NYC 1970).

But many of the people I know and respect are coming out with strangely unreasonable positions on all this. And I suspect this has to do with a kind of cultural failure. A society that cannot rise above the level of Game of Thrones or Harry Potter culturally, is one that may well have a hard time integrating the deep and complex emotions of mass death and violence. And several artists have come to mind during this period. Hilton Als has a nice article at the NYRB on Agnes Martin. And Martin, in retrospect, simply gets better and better. The second artist is Franz Xavier Messerschmidt the 18th century Bavarian born sculptor. Often when people first see one of Messerschmidt’s bronze or tin alloy busts they assume, with good reason, that this is a contemporary artist. For the madness of Messerschmidt is a very contemporary madness. His is the madness of the Enlightenment.

“There is an infinite sadness to the art of Franz Xaver Messerschmidt. Perhaps it is the lead and tin alloy from which he created his grey-glinting heads that weighs on the soul. Perhaps it is the resemblance to death masks that haunts his microscopically detailed reproductions of human physiognomy. But more likely it is the prison of his mental illness whose door slams on you as you are drawn into his extravagant monomaniac vision.”

Jonathan Jones

Messerschmidt somehow feels very contemporary, the *hyper-realism effect* that is really a subtle exaggeration of certain aspects of physiognomy, creates a sense of self absorbed mania. But Jones is right when he suggests the connection to death. The sense of theses busts as death masks is acute. And this in turn reminds me of Antonio Gaudi’s death, and Benjamin’s own death, and finally it links in a way to Agnes Martin. For Martin was that most hermetic and solitary of painters, and one who, in her own words, turned her back on the world. And Martin is the artist, to my mind, who most connects to the sorrow of societally unintegrated grieving. The inability to grieve sort of kicks the grief can a bit further down the road. Gaudi died in the pauper section of a hospital because he was mistaken for a beggar. As if beggars deserve no better. And Benjamin’s death which now has resulted in a small cottage industry. In fact, Benjamin’s death fits neatly into his Arcades project. If the arcades were built for Napoleon’s return from Egypt, they were also the repository of colonial looting and conquest and subjugation. All was put on display, as display itself was put on display and as those strolling through the arcades became part of the displayed plunder. Today, Benjamin’s own death feeds the niche market of academic post graduate writing, and by extension today a kind of regressive political identification with the status quo. That status quo that allows stipends of a sort, enough, to keep the younger professional academic from the street.

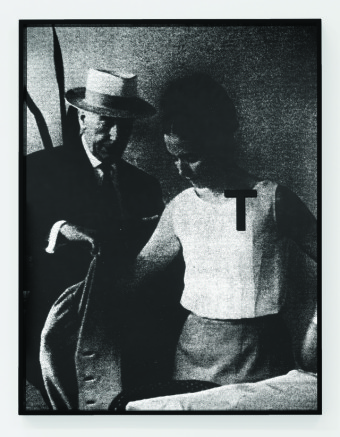

Agnes Martin, in her studio, apprx 1953.

Benjamin said that death sanctioned everything the storyteller has to say. And yet, today, the erosion of narrative — both its creation, and more importantly, its interpretation, is acute. You would think the constant reminder of death would elevate a structural relationship to the subject, but quite the opposite has happened.

Esther Leslie, writing on Benjamin….“Such a task is undertaken by Benjamin in a lecture for children from 1930. ‘Rental Barracks’ is an exploration of the architecture of Berlin, drawing on the work of Werner Hegemann in Das Steinernde Berlin. It begins by noting how the city’s forms have emerged from military needs. Since the reign of the Hohenzollerns, Berlin has been a military city and, at points, a third of its population was connected to the army, either as soldiers or their dependents. In the early days, the soldiers and their families were billeted in the homes of other Berliners, but by the late eighteenth century there were too many to house this way. Barracks were built for combatants and their families, and all remained inside these structures under virtual house arrest. The architectural solution of the barracks, Benjamin goes on, was adopted across the city, as Frederick the Great commanded the city be built into the sky to house a growing population. The Prussian military state condemned many people to overcrowding, lack of air and light and miserable housing conditions.”

Adam Pendleton

The military and architecture, the military and capitalism. These are trajectories in which can be found the hidden tracings of collective insanity in Western society. Today, the presence of the military in the U.S. is hegemonic, it occupies every representation, every story. Everything. Hollywood has not made an anti war film since, perhaps, Sidney Lumet’s The Hill (1965). Today, the token anti war film is rarely that, and more a dissection of bad apple syndrome. There has been a pronounced…drastic increase, really….in depictions of camaraderie and loyalty among those in uniform. There is never NEVER a criticism of the uniform. Never. There is a fawning obsequience demonstrated to those who wear uniforms as well as a validating of all expressions of unthinking obedience. Much is made of *yessir* and *no sir* and the like. Hollywood has come to almost traffic in subtle sado masochist ritual. Even a film such as One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, would today seem wildly subversive.

The point is that capitalism has reached a point of incoherence, from a theoretical point of view. The irrationality of a society that pits (what James Petras calls) a political psychopath against a clownish misogynist millionaire celebrity, and have the greater fear directed at the clown is a society that is now engaged in an auto pilot self analysis. Everything feels as it is a bit of psycho drama. In social media I am daily appalled at the expressions — pitched at the level of hysteria — of fear and desperation regarding Trump. And this is from otherwise very intelligent and educated people. Now, it is not that fearing Trump is wrong in and of itself, but that it is wrong to so little fear Hillary Clinton, to not include in this reaction of horror the figure of death that is Hillary Rodham Clinton. For if anyone needs to feared it is Hillary.

Gregor Hildebrandt

But perhaps the problem resides exactly there. The figure of Death. The Enlightenment began a long process of instrumentalizing thought, of cateloguing and measuring and defining. And science came to be more than just an effective tool for solving and even controlling Nature. It became a cult. And it began to harbor secrets the better to imbue its high priests with special gifts and powers. At the same time, the removing of religious dogma removed not just the irrational, but the very idea of ritual. Ritual space was lost, and with it a part of social history.

“…with the occurrence of death a dismal period begins

for the living during which special duties are imposed upon

them. Whatever their personal feelings may be, they have

to show sorrow for a certain period, change the colour of

their clothes and modify the pattern of their usual life.”

Robert Hertz

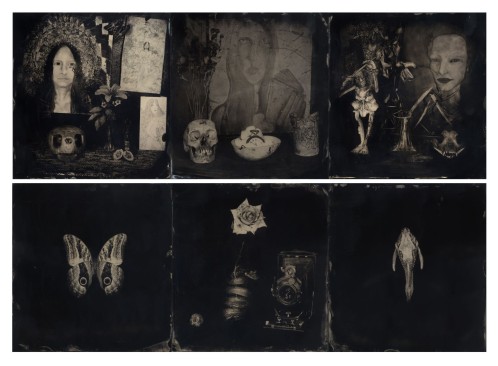

Chris Keeney, photography.

The shootings in Orlando, and the Brexit vote are connected. And they are connected by the reactions of the bourgeoisie in the West. The shallowness, the superficiality of the collective. Without meaningful rituals the best the educated classes can up with are calls for gun control, calls that are expressed with an almost religious intoxication. A kind of zealotry almost. The affluent gay white male in the U.S. is one caught in a class contradiction, in a sense. There is, as Andrew Wimmer pointed out, a reflexive appeal to the police, to the uniforms. And how deeply that identification or attraction goes is anyone’s guess. And two a mourning for those shot at the gay nightclub Pulse. Shot by the son of a crazy zealot father. Again, assuming the cover story is the truth. But there is no solidarity with the Israeli occupation and incremental genocide of Palestinians. No solidarity with those caught in the U.S. gulag prison system. No solidarity with the victims of right wing militarism in places such as Honduras — courtesy of a coup designed by Hillary Clinton and Obama. Why? Most gay white men and women I know, and most polls I’ve read, suggest overwhelming support for Hillary Clinton.

On social media the last few weeks I have read the increasingly shrill white knuckle writings of the half educated phantom middle classes in America. The barely employed or half employed who toil in acute anxiety all the time. ALL THE TIME, but who identify with the imaginary country that Hillary Clinton has drawn up for them. I knew someone who once said, apropos of LA Dodger’s iconic broadcaster Vin Scully, “I want to live in Vin’s world”. And I understood that. It was a happy place of normalcy. Well, for the marginally educated Hillary’s world holds a lot more appeal than Donald’s world. But this is all illusion. And why is it not read as illusion? Id suggest because everything is illusion and hence most people seemingly cannot distinguish.

This does not account for the serious critics of Empire who seem to have lost sense of proportion regarding Donald Trump. But the same logic is at work in the reactions to Brexit. And it is in these reactions that one can really gauge the contempt that the liberal class has for the poor. How dare they not vote as they should! There is no winner in the Brexit referendum, but the vote at least was an expression of genuine anger. Often at the wrong people, certainly, but still a call of anger. And that is something. And yet for many, if not most Americans the vote was being discussed as a huge blunder. For whom? It is a neo colonial mind set that is very slowly surfacing in this — the trace memories of the plantation overlord. The chain gang boss. You do as you are told boy.

Victoria & Albert Museum. Small Stories; History of Dollhouses. 2016.

And when I say that culture intersects in a meaningful way here, I think it is worth going back to Agnes Martin and Messerschmidt again. What an Agnes Martin achieved was not accidental. Hers was a story not unlike any number of other major 20th century painters, of difficult childhoods in wide open spaces. The west and mid-Western (and in Martin’s case the Canadian prairies) plains and deserts were the places of spiritual pilgrimage for countless artists. Martin was also linked to a generation of gay artists in NYC (she lived at Coenties Slip for almost a decade) such as Robert Rauschenberg, Ellsworth Kelly, and Jasper Johns. But Martin was the least interested in fame or approval. And finally in people altogether. She lived most of her later years in rural New Mexico in a house she built herself, without electricity or TV or much of anything else. And that distance, that quality of autistic psychological isolation is seen in the substantiality of her work. It is not, as Rosalind Kraus might have it, the thing and not the representation. Rather is is the thingness OF the representation. It is ur-painting. Now, what does this have to do with the Brexit vote or Omar Mateen, or Trump, you ask. Well, to answer that means to more deeply track the growth of mental illness and character disorders in the bourgeois West. For that is what I think, partly, is happening.

“For Freud, every mental structure contains movement, in which a ‘psychic conflict’ can be isolated. Consequently, his idea of structure comes down to this immanent dynamic and not to some ahistorical constellation of rigid relations. The minimum of structural stability can be located in the processes of condensation and displacement, which find their linguistic equivalent in metaphor and metonymy.”

Samo Tomsic

Maik Wolf

Tomsic’s term is one I quite like..’The Capitalist Unconscious’. This unconscious has found expression, increasingly, over time, in socially conditioned ways, with socially vetted structures.

“Lacan introduced and deployed his controversial thesis that

there was a wide-reaching homology between Marx’s deduction of surplus-value

and Freud’s attempts to theorise the production of enjoyment. The production of

value in the social apparatus and the production of enjoyment in the mental apparatus

follow the same logic and eventually depend on the same discursive structure.”

Samo Tomsic

And this in turn relates to the unreality of death for contemporary westerners. And that unreality is part of what makes people crazy. The manufacture of enjoyment (and it is worth exploring enjoyment as distinct from distraction, etc) is compulsive today, and it becomes a search for tension, for ever more tension. The paradox of anxiety feeding off that which is compulsively sought.

“Among the Dayak of southeast Borneo, the final resting place of the body is a small house, made entirely of ironwood, often finely carved, and raised on fairly high posts

of the same material; such a monument is called sandong, and constitutes a family burial place which can hold a large number of people, and lasts many years.”

Robert Hertz

Thomas Ruff, photography.

There was a show at The Victoria and Albert Museum (also, perhaps coincidentally, reviewed in the NYRB) on the history of dollhouses. This exhibition focuses on mostly Victorian English miniatures, but there is a place for such shows on north German and French miniatures, too, certainly. Dollhouses are death houses, which is why children play with them. Boys can’t play with dolls in the West, but they do, only they call them *action figures* with names such as G.I. Joe and the like. I remember having a castle I quite liked when I was a boy. And little molded plastic soldiers to move around in said castle. But the point is, the overriding import of miniatures is, so I believe, death. When Hertz (whose book on death remains essential reading) writes of the Dayak people of what was then Borneo, the rituals of burial included transformative effects for the living. Periods of being forsaken and shunned, and then later, if later, reintegrated into the societal fabric. The dead do not live on, they reside in death, as death, in their funeral homes on stilts. One of the curious factors in Western Christian notions of death is the idea of manufacturing a false eternity for the departed. So many Western rituals are based on creating an eternity — it is a massive denial of death’s finality. It is not exactly eternity, however. It is a kind of kitsch after life, the point of which is to mediate and lessen the need for grief. And hence, western art is always dealing with very sharp and pointed representations of death, both intentional and unintentional. All these factors are coming together, I think, in a new social madness. The creation of doll houses is the pursuit of domination mediated by a hidden violence I associate with the sentimental.

How to explain the conversations one has, and the Op Ed pieces one reads, the over all discourse on event such as Brexit? Or on Hillary. Or gun control. I mean the bourgeoisie in the West, meaning mostly the U.S., are terrified of their own terror and feelings of contempt, for the underclass. This mock middle class congratulates itself in various cultural production for its tolerance and values, but all the while a deep seated terror is driving toward the surface (as it were). And the natural reaction is to repress such unacceptable ideas. But my suspicion is that these mechanisms of repression no longer work. The educated white liberal class fears its own animal nature, but even more it fears that all people are bad and savage and eventually will become marauding hordes (ISIS essentially).

The manufacture of enjoyment is pathological under Capitalism. It is also, perhaps, not very enjoyable.

“Capitalism is inscribed in the mental apparatus—this was already Freud’s insight,

when he found the best metaphor for unconscious desire in none other than the

capitalist, meaning that psychoanalysis began with a fundamental critical and political

insight rooted in the rejection of the opposition “unconscious—conscious” or

“private—social.” The unconscious is no archive or reservoir of unclear representations

and forgotten memories; it is a site of discursive production.”

Samo Tomsic

Simon Boudvin

And this is not a matter of ideological position, or opinion; it is, regardless of opinion, the intensity of the expression. I have never in my life felt so many people wanting to fight over the slightest disagreement. There is a growing sense of panic.

“So, too, Death, repressed through medicine and hygiene, has reinfected our sexuality with a hitherto unheard of virulence…finally, accompanied by anxiety, despair, and violence, death has gained a foothold within the psyche itself. The forces of destruction and self-destruction, latent in each individual and society, have been reactivated in our anonymous urban milieusl multiplying and amplifying the solitude and anxiety of individuals, disinhibiting a violence that becomes the banal expression of protest, rejection and revolt.”

Edgar Morin

Hede Xandt

The legacy of the Enlightenment has meant that, as Morin puts it, a paradigm of disjunction/reduction controls our thinking. And this has led, in a general sense, to an isolating of objects and phenomenon from not just their environments but from history.

“Conformism here refers to the energies of conventional interpretation.

These ensnare tradition and the receivers of tradition in

tales devised, or at least approved, by the ruling class and its

ideology-mongers. The accumulated experience of the oppressed

is overwritten in histories that re-transmit the existing balance of

power: business as usual.”

Esther Leslie (Benjamin: Overpowering Conformism)

Today, it feels as if this overwriting that Leslie describes is no longer legible. The status quo is writing in invisible ink. But more, there is an inability to actually practice interpretation. On a rudimentary level this is the result of decades of disinformation in mass media. The age of marketing and spin has inured the public to distinctions of historical fact. The world is viewed from the subject position of someone watching their favorite TV show. And this is partly my appeal for the importance of artists such as Agnes Martin. And there are of course many others. It was Benjamin who, following the failure of the Spartakus revolt, began to seriously investigate the influence of technology (Tecknik) and the assumptions about the idea of progress. And as Leslie points out, he prioritized the role of culture and art as a form of training for revolution. In this sense he was quite in accord with Adorno, however much they may have disagreed about specifics. What mattered, thought Benjamin, was coming to understand the relations of production, and the conditionings of mass culture.

Dinh Q. Le

“Benjamin warns that the 1914–18 war cast just the shadow of a brutality soon to be superbly outbid. The armies of the future will deploy technologies of far greater destructiveness; troops will be immeasurably more sadistic and bloodthirsty; war will be total, and inescapable – it will be fought by new technological means.”

Esther Leslie

This echos Enzo Traverso’s reading of the first world war as the defining shift in humanity and its relationship to technology. Human relationships were being subsumed by the anonymity of technology. Benjamin came to see that a level of anger was necessary to cut through the conditioning of disinformation in mass culture. And this seems particularly relevant just now. One of the primary characteristics of contemporary Western society — or the contemporary bourgeoisie, is an expression of false courtesy. The panic that is gripping the societies of the West is under pressure to appear polite and reasonable. And this is not unrelated to how technology has come to create new ways of remembering (or not remembering). For we (those of us old enough) are exiles from our own history. The world of even fifty years ago is only a distant memory and a memory that contemporary culture works overtime to erase. For what has changed culturally over the last fifty years in the West, certainly in the U.S., is acute, but it is also constantly being obfuscated. We are being told over and over to not remember. That memory is suspect. And so it is, but not in the way corporate owned media would have us believe.

Mathias Olmeta, photography.

This false politeness is, however, it should be noted, mostly an illusion. But it does remain a kind of weird ideal. For the tenor of discourse on social media is awash in a kind of hysterical demand for agreement. And as a sort of side bar note, the meme about Democrats being inherently, no matter what, better than Republicans is one that is seemingly indelible. But I digress…for this sense of being exiled from one’s own past was prophetically outlined by Benjamin, and by Karl Kraus and Kracauer both. It was Kraus who saw the reporting of the first world war and the manner in which the subject shifted from the war to the coverage of the war. Benjamin pointed to the erosion of language, and most specifically the spoken word, in this mediation of the event by a press that in the hands of the wealthy. For Benjamin the mediation itself was not the problem. Rather, the mediation was inevitable, but memory could still be rescued. The fulcrum for representation of reality was the 1920s — for Benjamin saw the substitution of the snap shot memory by a cinematic memory. And this cinematic memory was more artificial. For experience is not processed in any kind of real continuity, but rather is fragmented and non linear. The Freudian idea of the unconscious was one out of time. The implications are enormous, if Benjamin was correct. Today I suspect people DO remember in cinematic terms, and it perhaps accounts for the rise of uncanny experience in still photography.

“The youth experience of a generation has much in common with

the experience of dreams. Its historical form is a dream form.

Every epoch possesses a side turned towards dreams, the child

side.”

Benjamin

The sense of panic, of exaggerated tension — the same one sees in Hollywood film and TV — is expressed as something of unique importance. It is always the most important election, the most important speech, the most important decision, and so forth. For anything less does not rise to the level of enjoyment. This very particular late Capitalist *enjoyment*.

And Leslie quotes from a late letter of Benjamin..

“The objects given by monastic discipline to friars for the purpose

of meditation were designed to turn them away from the world

and its affairs. The train of thought that we are pursuing here

emerges out of similar considerations. It intends to free the

political worldling from the ensnaring nets of those politicians

in whom hope had been placed that they would be opponents

of fascism, but who in this moment lie flat on their backs,

affirming their defeat with the betrayal of their cause.”

Paul WInstanley

The narratives of the state are uniform in their falseness. But they accompany representations of disproportionate official significance. The public senses, deep down, that this importance is not all that important. But to reflect on that fact fractures the cinematic process of enjoyment. Only the most excluded today are, at least partially, free of the directed dreaming. Prisoners, the homeless and insane, these are part of a demographic of no interest to the dream clinic. Consumption is pleasure. And everything becomes consumption. And consumption becomes manufacture, at a certain point.

The cruelty of an occupied dream life is slowly dawning on a public that has accepted the cinematic portrayal of their own life. And there is a sense that this *enjoyment* idea is mostly just a kind of stress.

Lorca wrote, in his essay on Duende….“The Duende does not come at all unless he sees that death is possible.” Lorca, in another essay on Deep Song, suggests the deep memory that is alive in Spanish and Gypsy music. The memory of ancient Arabian sensibility. Throughout his prose Lorca is consumed with images of graveyards and crypts, with funeral rituals, and with the collective memory of Spain. Such thinking is alien today. Artists search out business models and talk of brands. And the sudden fear that is in the air, a fear of *fascism*, a word scorned for decades, is driven by several things that are converging at once. One is guilt. An intuition that liberal collaboration has caused immeasurable suffering. And two, this recognition that we aren’t having fun. The endless efforts to dull these feelings has only served to intensify them.

Hollywood produces endless films and TV that are *suspenseful*. There are music cues and rapid edits, and all manner of manipulation — all in the service of providing suspense. The effect is not really suspense, partly because of the familiarity of these techniques. Audiences anticipate what comes next. Some version of the same. This anticipatory phenomenon exists with cues on when to laugh, or cry, too. So, really, the audience for these cues is reading the cue representations as one might have read hieroglyphics. The tension or suspense in thriller films is not experienced, it is read.

Tilman Riemenschneider, 15th century, Germany.

Today there is a quality of this false suspense in electoral theatre. But more significantly there is a quality of this false suspense in daily life. The obsessive texting and checking for emails, the selfies and the billions of apps — it is micro suspenseful. At a mall recently, in Prague, I stood looking down from the railing on the third floor, at a coffee shop on the ground floor. Every table was taken and at every table sat someone looking at their smart phone. What were they seeing?

Samo Tomsic in an essay Laughter and Capitalism …

“But for Freud the unconscious processes were all about a specific form of labour. Operations like condensation and displacement are no simple automata; they demand a

labouring subject, which, in the given regime knows only one form, labour-power. Hence, to talk about unconscious labour is far from innocent. Freud refers to the same economic reality and to the same conceptual apparatus as Marx.”

The coffee shop of mobile phone addicts was the new factory of unpaid labor. And nothing is enjoyable because the unconscious is suffering its own version of austerity. Capitalism cannot allow real culture. Eventually it must substitute the artificial version as it substitutes real tension with artificial suspense in its endless nearly identical product. Art and culture are the radical communists of the unconscious economy.

Franz Xavier Messerschmidt’s busts, fifty of which survive, were made during the last decade of his life. He had retreated from the Hapsburg Empire to a remote provincial outpost (Pressburg, now Bratislava) and began his obsessive focus on extreme emotional states. Most of the busts were likenesses of himself modeled off a mirror he sat before. What is unnerving is the modernity of these busts. Messerschmidt turned his back on the Empire and got on with it (another Agnes Martin expression). No doubt Zoloft might have helped Messerschmidt and kept him from creating. He might have continued in Vienna taking small commissions for busts of the Royal family. Messerschmidt is close in spirit to Goya and Bosch and even Donatello. But in an odd way the real precursor to Messerschmidt is fellow countryman Tilman Riemenschneider, a carver of wood. Riemenschneider worked at small projects, mostly around Wurzburg, and was a contemporary of Michelangelo and Durer. What sets him apart from other northern Gothic artists of the 15th century is the inwardness and sense of grief in his figures. This was something very different, really, from Durer, or any of the southern artists in Europe; and Riemenschneider can also be seen as one who had turned his back on the court. He favored, almost exclusively, limewood and rejected the idea of painting or adding polychromy. During his own time his work was described as *’altfrankisch’*, meaning old fashioned and Franconian. Riemenschneider was imprisoned after The German Peasant’s War, a revolt associated with the early Germanic capitalism and the birth of bourgeois society.

Speak Your Mind