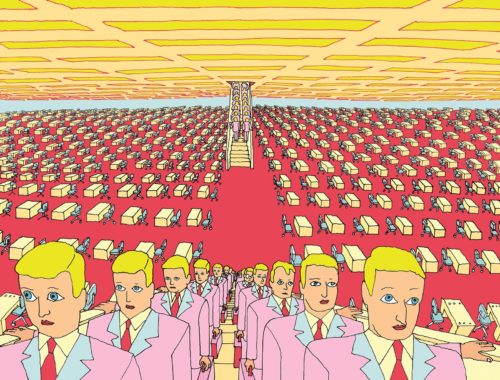

Pushwagner

“The literature of terror is born precisely out of the terror of a split society and out of the desire to heal it. It is for just this reason that Dracula and Frankenstein, with rare exceptions, do not appear together. The threat would be too great, and this literature, having produced terror, must also erase it and restore peace. It must restore the broken equilibrium — giving the illusion of being able to stop history — because the monster expresses the anxiety that the future will be monstrous. His antagonist — the enemy of the monster — will always be, by contrast, a representative of the present, a distillation of complacent nineteenth-century mediocrity: nationalistic, stupid, superstitious, philistine, impotent, self-satisfied. But this does not show through. Fascinated by the horror of the monster, the public accepts the vices of its destroyer without a murmur, just as it accepts his literary depiction, the jaded and repetitive typology which regains its strength and its virginity on contact with the unknown. The monster, then, serves to displace the antagonisms and horrors evidenced within society to outside society itself. In Frankenstein the struggle will be between a ‘race of devils’ and the ‘species of man’. Whoever dares to fight the monster automatically becomes the representative of the species, of the whole of society. The monster, the utterly unknown, serves to reconstruct a universality, a social cohesion which in itself would no longer carry conviction.

Frankenstein’s monster and Dracula the vampire are, unlike previous monsters, dynamic, totalizing monsters. This is what makes them frightening. Before, things were different. Sade’s malefactors agree to operate on the margins of society, hidden away in their towers. Justine is their victim because she rejects the modern world, the world of the city, of exchange, of her reduction to a commodity. She thus gives herself over to the old horror of the feudal world, the will of the individual master. Moreover, in Sade the evil has a ‘natural’ limit which cannot be overstepped: the gratification of the master’s desire. Once he is satiated, the torture ceases too. Dracula, on the other hand, is an ascetic of terror: in him is celebrated the victory ‘of the desire for possession over that of enjoyment’, and possession as such, indifferent to consumption, is by its very nature insatiable and unlimited. Polidori’s vampire is still a petty feudal lord forced to travel round Europe strangling young ladies for the miserable purpose of surviving. Time is against him, against his conservative desires. Stoker’s Dracula, by contrast, is a rational entrepreneur who invests his gold to expand his dominion: to conquer the City of London. And already Frankenstein’s monster sows devastation over the whole world, from the Alps to Scotland, from Eastern Europe to the Pole. By comparison, the gigantic ghost of The Castle of Otranto looks like a dwarf. He is confined to a single place; he can appear once only; he is merely a relic of the past. Once order is reestablished he is silent for ever. The modern monsters, however, threaten to live for ever and to conquer the world. For this reason they must be killed.”

Franco Moretti

“Donald Trump is being presented as a lunatic, a fascist. He is certainly odious; but he is also a media hate figure. That alone should arouse our scepticism.”

John Pilger

“Not all people exist in the same Now.”

Ernst Bloch

Moretti points out that in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, the basic overview is binary. Society is split. The reactionary core of this vision is making the proletariat monstrous. As Moretti says, the struggle between the monster and the scientist prefigures future social relations. There are similar motifs running through Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Jonathan Harker is appalled that the Count has no servants. That he stoops to cooking meals and driving his own carriage. The Count does not even enjoy the blood he sucks, he is simply filling a need (and never wastes a drop). Dracula is the repressed libido of Victorian England surfacing and disrupting the social order (David Pirie). Vampires in total are figures of ambivalence. And in that sense they are figures of sexual release, but also avatars of unreason and loss of control. But as Moretti correctly observes, the repressed returns, but as a monster. And the monster is that device, in terms of narrative, and that image, that makes bearable the desires and fears of the unconscious. This image is itself, however, fraught with contradiction. First, as Moretti says, Dracula is the symbol for monopoly capital, but capital itself is also the mother. All of this hidden beneath his black cloak. This blackness is found in Shakespeare as well, from Othello to the storm in The Tempest. There is a messianic aspect at work here, of which Benjamin was acutely aware. The metaphoric role of the monster, then, is one with an outward projection — the better to link it with mystical significance and the supernatural. Treating the monster as literal (as, say, witches were treated literally, and literally burnt) is a kind of safeguard. This is also one aspect of science fiction today, except it is often merged with nostalgia (Netflix’s current Stranger Things is maybe the perfect example). Rather than create a dystopian future, the story is set in a 1980s that never really existed except in the films of Speilberg and John Landis.

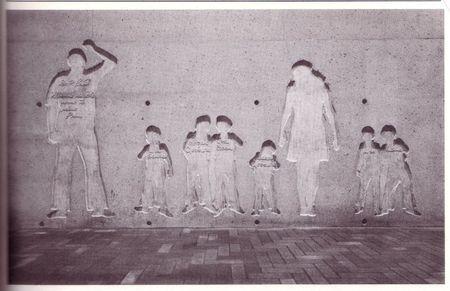

Colette Whiten

“This is the literature of dialectical relations, in which the opposites, instead of separating and entering into conflict, exist in function of one another, reinforce one other. Such, for Marx, is the relation between capital and wage labour. Such, for Freud, is the relation between super-ego and unconscious. Such, for Stendhal, is the bond between the lover and the ‘illness’ he calls ‘love’. Such is the relationship that binds Frankenstein to the monster and Lucy to Dracula. Such, finally, is the bond between the reader and the literature of terror. The more a work frightens, one the more it edifies. The more it humiliates, the more it uplifts. The more it hides, the more it gives the illusion of revealing. It is a fear one needs: the price one pays for coming contentedly to terms with a social body based on irrationality and menace. Who says it is escapist?”

Franco Moretti

The messianic is there in the nostalgia for totality. It was Derrida who saw Benjamin’s interest in ruins as a search for the ghost of unity and reason. A totalized reason. Whether this is true or not (I’d sort of doubt it, actually) the observation still has relevance. For there is a deep long standing connection between nostalgia and fear. Nostalgia, as Bachelard noted, is a desire to return to the nest. In the current Netflix franchise the nest is a filmic 1980, where it is safe to let loose the monster. And here is where the current electoral circus of the U.S. enters the discussion. For Trump is the monster. That is his role. And whether or not the Clinton’s employed him for this, it is the role he seems to enjoy playing. Julia Kristeva began to write about a kind of collective depression in France (but really, all over the West) in the 1980s. For no longer was identity centered around notions of stability and prosperity, but was being increasingly formed negatively through an internalized system of racist stigmatizing and colonialist logic. Adorno wrote, in Minima Moralia …“What philosophers once knew as life has become the sphere of private existence and now of mere consumption, dragged along as an appendage of the material process of production without autonomy or substance of its own.”

Julian Goethe

Elaine Miller, in a good book on Kristeva, notes that for Kristeva, modern society is in a kind of search for a string of lost objects, traces of which are found in the endless memorials to pseudo important figures, or the monuments that in normal {sic} cultural formation are there to memorialize events, but today are expressions of melancholic need.

“Melancholia is the state of mind in which feeling revives the empty world

in the form of a mask, and derives an enigmatic satisfaction in contemplating

it. Every feeling is bound to an a priori object, and the representation

of this object is its phenomenology…”

Walter Benjamin

“If the depressed person does not commit suicide, he finds some relief for

his pain in a manic reaction: the depressed person mobilizes himself in

pursuit of some enemy, preferably imaginary, rather than berate himself,

restrain himself, or shut himself up in inaction, then engages in wars, in

particular holy ones.”

Julia Kristeva

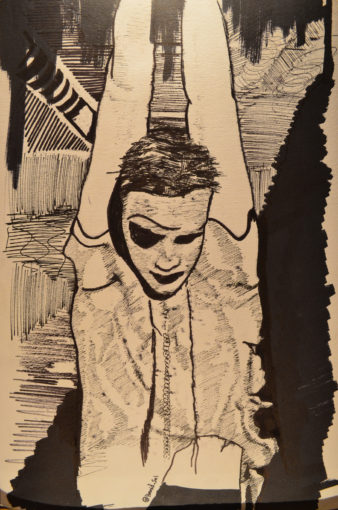

Hamid Sulaiman

The mania of contemporary culture, in the West, tends to pass less noticed. Less noticed by the West, that is. The current and growing hysteria of the white liberals in the U.S. is centered around Donald Trump. The monster. But Trump is being accused of a potential that is already existing (as Pilger noted). Trump is the monster of nostalgia in a sense. He is perceived almost as if existing in the past. Like the monster in Stranger Things (Netflix), which arises in the 1980s, and an imaginary 80s at that, Trump *must be stopped*. Stopped to prevent what has already occurred.

There is a sense in the current state of depression (collective and individual) of a longing to renew a capacity for desire. Just that. And this was Benjamin’s sense of Weimar before Hitler came to power. An irretrievable past. Miller quotes Eric Santer, that melancholia emerges… “out of the struggle to engage in the labor of mourning in the absence of a supportive social space.” The rehabilitation of an individual past becomes a kind of disfigured allegory of self. Trump generates a pseudo fear, then. For this is a culture, in the U.S., in which mourning is short circuited. The loss of empathy is partly the result of a loss of collectivity. And here arises a question of Death as it functions symbolically in the West today. The ascension of Zombie narratives is related to this, I suspect. The denial of death is partly the result of commodity fetishization. The constant reproduction of the same. Infinitely replaceable. Reification means that *things*, while dead, also return. They are replaced. And the hostility in the bourgeois class toward the poor has shifted from seeing them as a surplus population to one of seeing them as a disposable population. For what matter, they can be and will be replaced. Objects are no longer repaired, even. They are replaced. Planned obsolescence for culture overall. The past then, today, looms as a district of kitsch nostalgia. One in which desire and eroticism still existed. Even if, in their representations, this is hardly true.

Miller again, quoting Rebecca Comay…

“Symbolic resurrection—‘vision’— . . . calls up the dead as objects

of consumption: the mourned object devoured or introjected as host or food

for thought. Allegorical resuscitation—‘theory’—throws up the dead as indigestible

remainder and untimely reminder, the persistent demand of unsublimated

matter.”

Florian Pumhosl

The sense of need for villains, then, is linked to the depression of disconnectedness and general alienation. The monster is external. He and not we are the problem. I notice in this current Presidential race, an upswing of mock remorse or guilt. This too is really an outward projection. Trump is *our* problem and we have to fix it. The monster, though, even if part of an infestation, is always an isolated issue. One must take out the trash, not actually change anything. The pseudo fear and pseudo guilt are the reenactments of a kitsch society – one that is borrowed from this nostalgic past. (I am willing to bet on a huge uptick in Hollywood of *old fashioned* narratives of heroism). Moretti noted how many monsters there were in the English novel. And this was partly the question of upward mobility, in Victorian England in particular. And the durability of Gothic tropes, too, today, suggest the style codes of colonial thinking remain hugely attractive to the bourgeoise. Trump is also the usurper. The unacceptable dinner guest. His orange hair and sun lamped skin are vulgar and crass and the RNC convention set was almost cartoonish. He is come as a stain on the institutions of the status quo. The Gothic imagery of darkness and aliens and foreignness are reproduced as their opposite, almost. Bright, garish, American — but of the wrong class. Trump’s racism is a means to jettison one’s own racism. His almost childish speech and idiotic bigotry — walls and deportations and the like, are ready-mades that can be conquered by white refinement. And this obvious dynamic needs alibis. So employ Snoop Dog and Lena Dunham. Trump is literally of the past. Not hip (Scott Baio?) and out of date. Still, the fear is the selling point. The white liberal would have been hugely disappointed if Paul Ryan got the nomination. Trump is much more fun. For this is the theology of white liberalism. The constant refrain on social media now is one of responsibility. One must put aside one’s dislike for Hillary and do what is *right*. No more shilly shallying with truth and history and fact. These are things of scorn, now. To even raise the issue of Hillary’s sordid record is cause for hysterical abuse. The hostility toward the left and socialist thought among liberals has grown exponentially during this election. I cannot count the number of times I have read attacks on the left in the guise of refusing to see the existential threat that is Donald Trump.

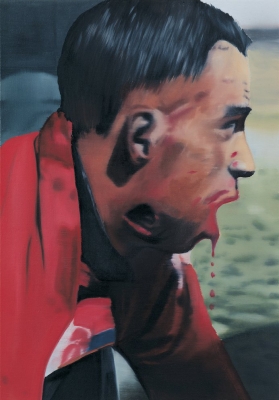

Elizabeth Glaessner

I think there is another factor in all this hysteria. And that is resentment. The need to blame is crucial in the managing of shame. The offending party must not just be blamed, but must confess their crimes. But this equation mutates in the collective, in a sense. For the narcissist subject must himself confess to crimes he or she doesn’t really believe. The act of confession is an act of superiority. It relates as well to a kind of management of shame. This is seen in the *we are all to blame* mantra. We are all guilty. The bourgeoisie are addicted to confession. For the act validates their superior moral guidelines. It also grants permission to attack the *other*. And the other in this case is the proletarian Trump base. And Hillary Clinton’s basically vindictive nature is perfectly suited for the role of Grand Inquisitor. And it is probably a useful addendum to this topic to revisit Dostoyevsky’s famous chapter of the same name.

There is no sympathy expressed for the working class that follow Trump. The majority are openly racist, true enough. And most are not highly educated. Still, this is the working class abandoned by the Democratic Party. A class no longer protected by unions or even community tradition. I see only contempt expressed. A hatred of leftists and of the redneck poor, or redneck workers. Lip service is given to the poor, of course. But little awareness is exhibited for the slashing of social services under recent democratic presidents. Or the fact that the military uses economic conscripting to fill the quota for cannon fodder. The bourgeois class in the U.S. is a seething resentful self hating cauldron of spite and animosity. That catered sit in, again, was the theatrical expression of elite condescension to the disposable poor. Crocodile tears, and a clear blame given to the underclass that love guns. A love driven by, capitalized on, and manufactured by ruling class entertainments.

Diego Velazquez (1620).

“Adorno and Kristeva share a concern for the historical development of the

concept of nature. They are both concerned with how a dominant paradigm

of discursive and instrumental reason has overshadowed any other possible

access to nature and the body and how the abject other has been aligned

with nature. Both speculate as to whether art might be able to give a “voice”

to these suffering remnants. Kristeva, Benjamin, and Adorno have a common

interest not in overcoming melancholia, since it is an important symptom

manifesting the disorder of our time, but in exploring ways in which melancholia

might be tempered in such a way as to point to another way of

existence.”

Elaine Miller

Both Kristeva and Adorno see the role of art as transcription. A transcribing of suffering. And for Adorno, as often noted, any artwork that achieved a unified meaning would be collaborating with the system it is critiquing. And this is the sensibility of the corporate driven art economy — reconciliation. Politically this is expressed by the drum beat of support for Hillary Clinton. Reconciliation — the American longing for Empire, for aristocracy, and inquisition. Nobody would send the revolution to its death quicker than white liberals. While racist police forces operate a kind of assassination squad across inner cities, the only upward mobility for blacks is symbolic. The star entertainer or athlete is often crowned literally as King. The U.S. today is a strange reincarnation of Victorian England. The Clintons, like the Bush family, represent the legitimizing of white aristocratic rule.

In Hollywood there is marked reluctance to allow melancholy. In contemporary art, there are artists who are finding something that suggests a reconfiguring of the uncanny — an anti Gothic in a sense. One is allowed to remember, but must remember that which is licensed as memory. If today the 1980s, and 1970s are the material of nostalgia, the more remote past becomes the stuff of pure invention. Hollywood no longer even pretends to a historical accuracy (not that they ever much did) but the result is now a preference for the fantasy past. This is all a part of this fabric of managing shame. In Kristeva’s The Horror of Abjection, the title of one of her chapters is *I am Afraid of being Bitten, I am Afraid of Biting*. This is a pretty neat summation of the current electoral narrative in the U.S.

Eberhard Havekost

“In another domain of traditional U.S. ownership, Latin America, Clinton also seems to have followed Kissinger’s example. As confirmed in her 2014 book, she effectively supported the 2009 military overthrow of left-of-center Honduran President Manuel Zelaya — a “caricature of a Central American strongman” — by pushing for a “compromise” solution that endorsed his illegal ouster.

She has advocated the application of the Colombia model — highly militarized “anti-drug” initiatives coupled with neoliberal economic policies — to other countries in the region, and is full of praise for the devastating militarization of Mexico over the past decade. In Mexico that model has resulted in 80,000 or more deaths since 2006, including the 43 Mexican student activists disappeared (and presumably massacred) in September 2014.

In the Caribbean, the U.S. model of choice is Haiti, where Clinton and her husband have relentlessly promoted the sweatshop model of production since the 1990s. WikiLeaks documents show that in 2009 her State Department collaborated with subcontractors for Hanes, Levi’s, and Fruit of the Loom to oppose a minimum wage increase for Haitian workers. After the January 2010 earthquake she helped spearhead the highly militarized U.S. response.

Militarization has plentiful benefits, as Clinton understands. It can facilitate corporate investment, such as the “gold rush” that the U.S. ambassador described following the Haiti earthquake. It can keep in check nonviolent dissidents, such as hungry Haitian workers or leftist students in Mexico. And it can help combat the influence of countries like Venezuela which have challenged neoliberalism and U.S. geopolitical control.

These goals have long motivated U.S. hostility toward Cuba, and thus Clinton’s recent call for ending the U.S. embargo against Cuba was pragmatic, not principled: “It wasn’t achieving its goals” of overthrowing the government, as she says in her recent book. The goal there, as in Venezuela, is to compel the country to “restore private property and return to a free market economy,” as she demanded of Venezuela in 2010.”

Kevin Young and Diana C. Sierra Becerra

Diana Rattray

The collective depression of the bourgeoisie in the U.S. is linked to abjection (per Kristeva).

“Maternal authority is the trustee of that mapping of the self s clean and proper body; it is distinguished from paternal laws within which, with the phallic phase and acquisition of language, the destiny of man will take shape.”

Julia Kristeva

The fear of the archaic mother is fear of procreative power. And it seems, whether intentional or a vicissitude of history, that Trump arises as the figure of male repulsion. John Eskow’s very funny piece at Counterpunch (http://www.counterpunch.org/2016/07/21/donald-trump-is-the-loneliest-man-in-america/) was also rather perceptive in terms of both class and maternal authoritarianism. If the Gothic had Dracula as monopoly capital, then Hannibal Lecter is financial capital. The point though is that as Benjamin said, look at all that has happened and how little of it we have preserved of any of it. Carlo Ginzburg noted this in an interview when he wrote of his research on the witch burnings in 1391 in northern Italy.

“The werewolves in Livonia were led by a child with a limp. After a while I was struck by the number of myths and rites in which lameness plays a part. If one were to take as one’s point of departure a traditional historical approach, one would never find oneself wondering whether there was a historical connection – as I try to demonstrate in my book – between Achilles’ heel, Cinderella’s lost slipper, and the Chinese Yu dance, in which the feet are dragged to produce a jaunty, bouncing walk. “

The mythic register and then the rise of what is seen as realism, are both highly mediated. The current political narratives bear scant relationship to fact. Trump is obviously unappealing and yet he has never held public office. The fear of him is mythic. And allegorical almost. What is the meaning of his ridiculous hair? What is the meaning of its color or how it happens that Boris Johnson, another ridiculous figure with absurd hair has arrived at the same moment? The real story is the hysteria of the liberal class, today. For any rational calculation suggests Hillary almost cannot lose. And if she were to, by some accident of history, win– then that would be yet another story to unravel. But whoever is elected, certain things are very likely to happen. The U.S. military will provoke conflict, will look to dominate areas with resources they want, and will continue to try to break up disobedient states and replace them with small compliant micro states. And the ruling class will enact domestic measures to contain dissent, either through expanded prisons, even if called something else, and just simply gestapo like police tactics.

Richard Ross (photography.) Royal Scottish Museum.

The white liberals look to feel saved. They will luxuriate in self congratulation and feelings of having beaten the monster. The racism and bigotry and Trump are already here. The Islamophobia is already here. The psychotic meltdown of young men with guns is already a near weekly occurrence. Obama is already deporting record numbers of immigrants. No, beating Trump is beating a mythic monster. A projection that resembles Gothic aesthetic codes, only Jonathan Harker is now the liberal speaking on a TED stage. Or the manager of the local health food store. But the battle is to keep the body politic clean. How this intersects with the maternal authoritarianism of Clinton is yet to be fully discovered. But certainly the driving force for Trump’s followers is really hatred and fear of women, not racism or intolerance in general. This makes Hillary the ideal foil. I had first imagined Trump as a foil for her — and on a certain level he might well be a Clinton employee. But on the mythic level, Hillary is the foil for Trump. She is co star to his leading role as monster.

This election is Back to the Future. Its already happened. We must stop everything that has already happened. There is already a wall along the border where people already die. (Israel has a wall which is apparently just fine). There is nothing Trump suggests that hasn’t happened or isn’t already here. The argument is that it will intensify. Except that isn’t usually the argument. Torture? Trump will torture people. Gee, that’s never happened. And Trump serves another purpose. Amid all his crazy talk he mixes in a few very reasonable even very smart ideas. Disband NATO. Work with Russia. But because Trump said it, it’s got to be crazy. Once Hillary wins, the rhetorical ploy will forever be…’you sound like Trump’. This is what monsters do. The jingoism and open rabid xenophobia of Trump rallies is no different than almost any major sporting event in the U.S.

Stranger Things (2016). Netflix. Created by Ross and Matt Duffer.

Still, the germane aspect of this is the fantasy of liberal conscience. It was pointed out to me that Hillary supporters have no plan if she loses. Because there never is a plan. As Molly Klein says, the election is like a pageant. Once it’s over, it’s over. Wait until the next Oscars broadcast. Next election. The circus has left town. Tents are torn down. Yet, it is not as if the DNC plans have worked correctly, though. I suspect Sanders was not expected to be so popular. Or Trump. The growing support in the educated class, the bourgeoisie in effect, is part of a realization, or maybe only a feeling, that there is a society all around them in crisis. And so the need to erect a new reality. One that is usefully situated in the 1980s. Trump is an emissary from the past. And this speaks to the level of sleepwalking at work in contemporary consciousness. In Moretti’s construct, Dracula is the capitalist. Blood is capital. Dracula sucks the blood out of the people, of the workers. He hoards wealth. And Harker is a compliant prisoner in the castle of the Count, as everyone is contained within the system. The vampire metaphor is active in Marx, as has been widely noted.

“…the bourgeois order . . . has become a vampire that sucks out its [the smallholding peasantry’s] blood and brains and throws them into the alchemist’s cauldron.”

Karl Marx, 18th Brumaire

It is important though to examine the evolution of the Vampire figure. For prior to Polidori’s Vampyre of 1819, almost all vampire literature and myth featured female vampires. And so there is reason to see the sexual sub-text resonating with fear of the feminine. There was a widespread belief in vampires throughout Europe in the 18th century. And usually associated with vagabonds and outlaws. So this linkage of blood sucking, sexual excess and the feminine overlaps the transition from feudalism to Capitalism. And equates outsiders and strangers with disease and darkness. Marx repeatedly made the point of difference between living and dead labor. The allegorical element is striking, here.

Richard Wright

“…if the distinction is between accumulated and living labour, then it makes perfect sense to treat the former, capital, as ‘dead labour’. Hence ‘the rule of the capitalist over the

worker is nothing but the rule of the independent conditions of labour over the worker . . . the rule of things over man, of dead labour over living.’”

Mark Neocleous (quoting Marx)

Marx said the realization of labor meant a loss of reality for the worker. So the current mania around Trump and Hillary Clinton is one in which the monster must be situated, in a sense, in the past. For the bourgeoisie cannot reconcile the allegory of itself with a female vampire today. The loss of reality is so normalized today that I read a debate recently in which someone suggested they would vote for Jill Stein and was called a misogynist.

The imagery of Capital, however the early feminine was suffused with sexual excess, was drained of eroticism as it took on male characteristics. The financialized capital monster is one that needs no castle. The capitalist can indulge his hobbies, as it were, while his money keeps on making money for him. Hannibal Lecter recaptures some of the early feminine, albeit in a deformed version. Lecter is also, of course, a doctor, a psychiatrist. The master of persuasion. And his immortality is only in his finance.

Danny Lyon, photography.

Let me quote Mark Neocleous, from his excellent piece on Marx and Moretti…

“This argument in Marx’s ‘early works’ becomes transformed in Capital

into an account of commodity fetishism. While many writers have highlighted

the ‘metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties’ that run through Marx’s

discussion in the section on the fetishism of the commodity and its secret, and

have consistently pointed to the ‘magical’, ‘spectral’ and ‘spiritual’ dimensions

to his argument, what is relevant here is the fact that the fetish in question

concerns something Marx is describing as dead. Because capital is dead

labour, the desire to live one’s life through commodities is the desire to live

one’s life through the dead. What Marx is doing here is identifying nothing

less than the ‘necromancy that surrounds the products of labour’ (a necromancy

that ‘vanishes as soon as we come to other forms of production’, i.e.

communism).”

For contemporary liberal America the denial of Death would then serve multiple functions. That the U.S. economy is pinned to the defense industry suggests that Freud’s death instinct may need to be re-examined. The figure of the monster is always, to some degree, about denial and repression. The hysteria surrounding the Trump candidacy is both manipulation by a ruling establishment and the power of marketing, but also the necessary allegory of the bourgeoise that must live in the past.

Rembrandt (1630).

Trump himself seems aware of his nostalgic mythos. His slogan of *Make America Great Again* suggests a return to the past. That the country itself can erase the present, and even the immediate past and return to…well….when? When was America great? It doesn’t matter to most followers of Trump, but the answer is the 1980s. So there is a weird set of contradictions, or inversions, at work on this symbolic level. Trump campaigns as a return to the past, a white past, and his white followers support him because they desire a cleansing of the country. The Clinton supporters, mostly the bourgeois class, see Trump as a monster from this same past. And they want to defeat the monster who they feel will change the past they believe belongs to them. The fight for ownership of the past. At the same time they want to bolster the status quo. They fear interruption. And this is partly the Back to the Future mythology at work. Or Matrix or any number of other films that have seeped into popular culture as iconic. The liberal supporters believe Trump threatens the environment. This, despite the fact that Clinton is and has always been linked intimately with corporate America. And then there is the military, the world’s greatest polluter. And nobody wants to expand the military as much as Hillary Clinton. But the maternal real is Capital. And Hillary is seen as the daughter of Capital, I think. In that sense the identification of Hillary with the present — with a continuation of the present — makes sense. The eternal status of Capital. At a deeper level there is more ambivalence. More residue of the linkage with dead labor. And that linkage has residual Puritanism in it. The financialized risk averse bourgeois class disdains getting their hands dirty. These are people who dream of becoming ruling class. They own at least some property. They identify with wealth and the wealthy. One of the telling aspects of the Hannibal Lecter franchise was that Hannibal was the protagonist. Not even back in the Jodie Foster version was Hannibal not the central character and the one identified with. This is the necromancer identification. And it also explains the hatred of Communism. All the rhetoric about totalitarianism is not the real reason to dislike communism (besides being a fiction, mostly) but it is the loss of the Maternal real. The loss of that phantasmic property of dead capital. The financialized capital that goes on working so you don’t have to.

“In the course of economic history, the focus has shifted from material-intensive to

information-intensive technologies. These technologies make it possible to economize

simultaneously on the three classical factors of production: land, labor, and produced

capital. Information technologies can be embodied (in physical capital) or disembodied,

consisting of shared understandings and procedures (human and social capital).”

Neva Goodwin

Nicola Samori

The choice of the 1980s (and to some degree the 1970s) makes sense in that this was the pre computer age. Information technologies didn’t exist. Disembodied capital is a source of anxiety even as it is embraced. Hillary and her e-mails. Financial capital is also time shifting. It prophesies future gains, and deals in the immaterial. And this loss of material realism is felt as anxiety.

“Symbolic exchange is no longer an organizing principle; it no longer

functions at the level of modern social institutions. Of course, the

symbolic still haunts them as the prospect of their own demise. “

Jean Baudrillard

And speaking of financial capital a bit later, Baudrillard writes…“reversibility — cyclical reversal, annulment – is the one encompassing form. It puts an end to the linearity of time, language, economic exchange and accumulation, and power. For us, it takes on the form of extermination and death. It is the form of the symbolic, neither mystical nor structural, but ineluctable.”

Charles Ray

All of this seems to be coming together in the religious wars of contemporary American elections. The lost object that is at the center of psychoanalytic theory is imagined as hiding in the past. This is partly the appeal of all nostalgia. Financial capital is the allegory of lost objects. The linearity of time that Baudrillard saw as abridged results in this attachment to the morbid as an almost deified dream of time travel. Hollywood has reproduced this dream countless times over the last twenty years. For the present is annulment. Pathological repetitions and death. Clinton is the daughter of eternal Capital, and Trump is the monster from the past, delivered to the present as the avatar of disruption. His quality of datedness is what arouses the most fear. And in this sense he also represents the wrong class. He is a rube, and an embarrassment to the institutions that protect bourgeois fantasies.

“So self-accusation becomes an accusation against the other and selfannihilation

the tragic disguising of another’s massacre. Such a logic

presupposes, it is suggested, a severe super-ego and a complex dialectic of

idealization and devalorization, both of oneself and the other: the set of these

mechanisms is based upon the mechanism of identification. For it is indeed an

identification with the loved/hated other – through incorporation, introjection,

projection – that is effected by the taking into myself of an ideal, sublime, part

or trait of the other. This becomes my necessary and tyrannical judge. “

Julia Kristeva

I would like to respond in particular to your Miller quote, which I find interesting with respect to some of my own research that I am doing on architecture as witness, and, the most excellent and provocative historical account of the “art of memory” (research taken up by Francis Yates under a book of that title). There is certainly no way I can go into any sort of detail about this massive, and thorough historical work; however, I thought I would share a few observations that I think link up to Miller’s quote. Having read your online journal for a couple of years now, I know that architecture, space, and art are great interests of yours, John.

The quote in your journal that triggered this posting is the one next to the figure of the nun:

“Adorno and Kristeva share a concern for the historical development of the

concept of nature. They are both concerned with how a dominant paradigm

of discursive and instrumental reason has overshadowed any other possible

access to nature and the body and how the abject other has been aligned

with nature. Both speculate as to whether art might be able to give a “voice”

to these suffering remnants. Kristeva, Benjamin, and Adorno have a common

interest not in overcoming melancholia, since it is an important symptom

manifesting the disorder of our time, but in exploring ways in which melancholia

might be tempered in such a way as to point to another way of

existence.” -Elaine Miller

In Yates’ book, she presents to her reader a history of the art of memorization–an art that was once fundamental to ancient orators and to those who retained and passed on knowledge in society where literacy was scarce and copying out texts took an incredible amount of time. Curiously, the “classical” method of memorization was intimately linked with architecture, or space, and images. If one were to memorize a speech, one would walk about a building (say a cathedral), and memorize parts of the speech by linking it to details within the building along one’s course through it. Of course, i’m oversimplifying everything here–but the idea is that language-based text and its inherent meanings, ideas, and images, were linked via memory to spaces. Memory was the embodiment of our relationship to space. (Fucking beautiful!!!)

So, overtime, the art of memory changes and many of the changes we see–as Yates hypothesizes and illustrates them–come about from changes in technology and societies’ relationship with religion. Those writing memory treatises begin to expound upon methods that are more image-based than spatially associated. Image-based memorization might consist of imagining people or images that represent and remind one of the things meant to be remembered. Yates proposes image-based memory systems are connected to the style of paintings that depict gods holding various objects such as scrolls and scales, etc., because each object might stand for an idea meant to be remembered. According to Yates’ the art of memory is deeply embedded in, and connected to, the way paintings tell a story or give information.

In the 16th century, we see a dramatic drop in classical memory based on space, and there is a division between those who propound memorization rooted in image and patterning (this might include using zodiac signs or patterns in the starts to memorize), and those who propound memorization by repetition (Ramism). Ramism came about during the Protestant revolution in England when icons and buildings were destroyed. Ramism can be identified with Puritanism, and basically was the last step in eliminating not only the body in space from the act of memorization, but also imagery. The imagination was deeply suspect, and to memorize by using association with sensation or imagery was basically a form of consorting with the devil.

So, what does all this have to do with the above quote? Well… it is curious to me that early in Western civilization, there was such a deep connection between space, body, and text/speech. To practice learning a text, was an exercise in sheer relational embodiment with space and images. Imaginative thinking was imperative for remembering something (because there were no books, and certainly not hard drives, flash drives, google docs, etc.).

And that is something that colonial-capital-consumerist society can’t bear: to have people remember. To let those memories colour the way we see the world and understand ourselves. For instance, Canada was built up by killing and oppressing native, FIRST NATIONS PEOPLE, whose land and way of seeing/knowing the world the settlers have silenced and “forgotten.” As colonists, Canadians have not only forgotten the First Nations People, but we have also lied about, hidden, and forgotten our own violence against them. The memories and the history of this physical and cultural genocidal conflict–even if occasionally accurate in its depiction–is nevertheless, text-book based and disconnected from our bodies’ relationship with the land. Those memories don’t live in us. They live in books, disconnected. A very Western-based way of understanding the world: it is objective and separate from me: “the world does not concern me or my body, only insofar as I can hold it in my hand and look at it or appraise it.”

And of course, colonial-capitalist-consumer society also cannot bear imagination. If we remember by imagining ourselves walking through a space, or, if we remember by associating images with concepts and personalizing what we wish to remember–then the knowledge we wish to preserve becomes personal, and memorization becomes a practice in thinking for ourselves via exercise of the imagination. (And of course, god forbid that the people think for themselves!) …..This idea that i’m running with here seems very close to what Miller points out in the above quote, that Adorno and Kristeva are considering whether art can give a “voice” to the “suffering remnants”; if art is born of the imagination, then i highly suspect that it can…

thanks calla. I am ordering that book.

You’re welcome.

I think you’ll find the last few chapters fascinating too. They are about the art of memory as linked with Shakespeare and the Globe Theatre (I’m just getting started on reading that part now…). I’m not yet sure what Yates’ hypothesis is about these connections, but from my reading so far, and my own thoughts about the theatre, it seems to me highly provocative that the Space of the theatre stage is conceptualized (by Fludd) as an ‘actual’ space for memorized things to be laid down and remembered, while simultaneously, the theatre is conceptualized as a Space where the ‘actual’ and ‘imagined’ or ‘fictional’ world exist concurrently/inextricably. This overlap between material/embodied space, and fictional/imagined space as bridged through narrative & memory seems integral to me for how we might think about ontological questions in regards to ethics, and psychology.