Toba Khedoori

“Richard III, as he climbs great steps, gets smaller. As if he was seized and absorbed by the Grand Mechanism. Slowly he becomes only one of its wheels. He stopped being a hangman and became a victim.”

Jan Kott

“Lear, as character rather than king, becomes the vehicle for another

kind of ‘subjection’, evoking an ideological subjectivity in which the

reader/spectator can ‘live’ an imaginary resolution of irreconcilable

class projects.”

James H.Kavanagh

“I smash the tools of my captivity, the chair the table the bed. I destroy the battlefield that was my home. I fling open the doors so the wind gets in and the screams of the world. I smash the window. With my bleeding hands I tear the photos of the men I loved and who used me on the bed on the table on the chair on the ground. I set fire to my prison.”

Ophelia in Hamletmachine

Heiner Muller

“Art is like speech, for instance, in that it is at the end, and a shadowy replica of another

operation, thought. And even to name something, is to wait for it in the place you think it will pass.”

Amiri Baraka

When I began to write in Hollywood, and I sort of shudder to remember how ill equipped I was to survive in that world, at that time, I was told to adjust my attitude. I got it, business, this was about business. And I looked around and realized, oh, art is not a topic that anyone is comfortable with. My lawyer ….from the agency I signed with…he said, ‘you had the misfortune to actually take art seriously’. True too, in theatre. When I realized that the major institutional theatres in the United States demanded fealty and a sort of obedience to authority, to keeping the party line in tact, I saw that my future as a thriving equity house playwright was limited. Big theatres want young writers they can work with to develop hits, develop their subscriber base and also writers who are not difficult. Or perhaps its ‘difficult’. Difficult is really code for ‘wants to retain control’. Institutional theatres are in the business of neutralizing radical vision. Period. All of them. Full stop. What they do, often, is package safe political statement plays, but usually there is a white liberal’s point of view on identity politics at the heart of that theatre’s artistic footprint. Young playwrights today develop in MFA programs under the guidance of utterly middle brow sensibilities, or under resentful and petty minor playwrights who now inflict their rationale for how they came to be teaching rather than, you know, writing for Lincoln Center. Now, I get into all this because I think this society, in the U.S. anyway, but probably a good portion of Europe and Canada, has now found itself without even decent bureaucrats. The visionaries and radical voices, working class or underclass voices are all gone. And increasingly even the superior bureaucrat is gone. Or perhaps just extinct. I am echoing Curtis White, I realize, with his extended essay The Middle Mind. And perhaps it is more than even White implies. The West today, in the course of the last forty years, has lost whatever fragile but still transcendent hold it had on something of a real culture. The genius of Coltrane, or Shoenberg, or Rothko are not possible today. The last great living writer is no doubt Peter Handke. Bernhard is gone, Pinter is gone, Beckett and Genet. Instead of making lists, though, what this reality describes is the loss of a sensibility. A cultural sensibility that was at heart, spiritually, a radical sensibility. Coltrane was not overtly political, but his music is revolutionary, is radical. Bernhard was not conventionally political, but again, his preternatural ability to mold form and structure with a language and linguistic vision so hauntingly recognizible as issuing from the deepest layers of our psyche, that his work is unable to conform to expectations. It was inherently disruptive. Now there are contemporary artists and writers of extraordinary vision and discipline. And yet, even the best among them suffers under the weight of the whole, the administered society, the society of domination, suffocates them, and finally severely limits their voices …and not just limits audiences or readers being exposed to them, but actually physically silences them, or muffles them anyway. Jean Luc Godard still makes films, but they exist in the closest thing to a vacuum, societally, that is possible.

Chloe Sells

The sound of muffled speech is maybe the archetypal sound of contemporary Western society. The sound that is swallowed, the scream that never reaches the air. On some level this is the echo of a technological failure; the bad connection, which is a metaphor for disconnectiveness, for human isolation. On another level it is the stiffled testimony, the surpressed orgasm, the mute feature. It is a speaking while conscious of being recorded, and of being listened to technologically. The whisper was always conspiratorial, and so all hushed tones are tones of anxiety. The conspiratorial whisper has always been a factor of group psychology, going back probably to the dawn of human group formation. But the evolution of the whisper is worth looking at in terms of psychic strangulation.

Society today is like a narcissist that has laryngitis. The culture that thinks it wants to talk about itself, but cannot, because really, behind it all, it hates itself, and so finds ways to manufacture suffocation as a constant. A constant alibi and a constant justification for more justification.

Macbeth (1947) Orson Welles, dr.

And it is worth considering in this moment, the idea of what has replaced culture. There is a new film of Shakespeare’s Macbeth out now. And I want to look at several things in relation to this film. The first is the idea of theatre into film, the idea of filming a play written for the stage. The new Macbeth opens with a child’s funeral, which is not in the play. It then follows on with a lot of battle scenes, shot in slow motion on digital, and with anamorphic lenses (so I read in an interview with the DP), with the result being quite painterly at times, but painterly in the way expensive Mercedes commercials look painterly because it remains digitally hyper sharp. But herein lies the central issue with this entire project. Film always begs questions of verisimilitude — and this goes directly back to Jan Kott’s famous essay on Lear and Endgame. The truth of the *play* Macbeth does not reside in finding those PTSD parallels from contemporary life that seem to drive the director of this version. But there is another register here, before returning to the realistic portrayal of war and its effects on the psyches of soldiers, and that is that ‘vaulting ambition’ here, in Kurzel’s film is in the cinematography. It is an overly ambitious bit of cinematography. The auteur model here is with the cinematographer. Still, I could not help but think of Welles version of Macbeth. And I will return to that as well. But Shakespeare didn’t know, nor much care, about geographic accuracy. Scotland was an idea, not a geographical place. All of Shakespeare’s plays take place in a theatre — quite literally. When I staged Macbeth as part of a total experimental evening (meaning we staged about half the play, in fragments) I set the first witches scene, the opening scene of the play, at the end. And in the dark. And as the lights came up it was Macbeth, using three voices, and with finger puppets on three fingers, speaking the witch’s text like a puppet play for himself, alone.

Chimes at Midnight (1965) Orson Welles, dr.

I always felt that was rather brilliant (if I say so myself), and honestly it was as much John Horn’s idea as mine (who played Macbeth). The point is that realism is not even a relevant question. What does that mean here? With a writer who subverted realism at every turn, with geography and with history, and with an almost hallucinatory construction of plays. Once the landscape becomes a representation of reality, something has already gone wrong. By opening this film of the play Macbeth outside, and by focusing on this *landscape* the juxtaposition with the empty stage is emphasized. And yet, one cannot film an empty stage for that fails badly as cinema. One is not *on* an empty stage but filming it. Still, I think what can be done is closer to what Welles did, or with what was done with the Soviet film version of King Lear. Or, with Gospel According to St Mathew, the Pasolini adaptation of the gospels. The landscape that Jesus walks is both real and unreal. And it is the Biblical text that is traveling across it. The film can create a space in which absence, the offstage, is present as metaphor. One does not as a viewer ask questions of accuracy. That mimetic re-narrating — in the 2016 Macbeth — includes commentary on how austere and imposing the mountains are, and that is not a question one, as viewer should be asking. For we are not in a National Geographic documentary. There is NO REAL place that Macbeth is ‘set’. There is no real site for Macbeth that you can go visit on holiday, although there might be a real film location you can visit if you loved this film. Just as there is no real place corresponding to any of Shakespeare’s plays, and that includes the histories (although that I want to return to as well). Those opening battles scenes in this current version of Macbeth bring the film very close to Braveheart 2. In the play one does not see Macbeth right away. One hears about him. The battle scenes though, do something else as well. Situating Macbeth amid the swirling battle as a still figure, watching in slow motion the violence surrounding him, the pov of the camera is not that of Macbeth — we are watching Macbeth as he watches the slow motion. This is a problem, really, for in Shakespeare there is always an offstage, a theatrical place from which emissaries arrive. This is also a critical aspect of why theatre so often fails as film. The idea of character subjectivity is very different in each medium. Here, in the Kurzel film, the audience is watching the battle swirl just as we presume Macbeth is watching it. It is *presentational*, and it also being treated as representational. It is Shakespeare as if he were Arthur Miller. It is also too close to Shakespeare as if he were Game of Thrones. What would that scene be like if Macbeth, Michael Fassbender, were not in it? If the next Thane of Cawdor were absent. For his absence is very important to the opening of the play.

David George, photography. (Hackney at Night).

In the theatre, in Shakespeare’s plays, the *idea* of place and history are sampled in a sense. Venice or a magic forest, or an island run by a magician, or an early version of England, so old as to be lost in misty antiquity. In Lear for example, we open on a scene of the King with his daughters. Where are they? They are in a theatre. But the audience understands that there are places where Kings rule, and they know families in which the rivalries of daughters or sons infects households. So it is in Macbeth, a remote and violent region of a cold remote north. One of the oddest things in this current film is the brief cue card at the top which *explains* there is a civil war going on, blah blah. Needless to say there is no such explanation’ in Shakespeare. I don’t know if this exists in Hollinshed even, in any form. So, what is the point of it here? In the play everything occurs offstage. All the violence. Again the dagger speech is one that is most effective, often, the less one sees a dagger at all. Shakespeare goes to great rhetorical lengths to saturate the atmosphere with violence, with blood. It is most certainly the most blood soaked tragedy of Shakespeare, and yet nothing occurs on stage (compare to the mass death in Hamlet for example, but which does not make Hamlet at all a violent bloody play, except in a most secondary way). The violence is a metaphysical violence. Kott’s ideas on fate, on the slow turning of the *grand mechanism* were embraced by east European directors in the seventies (Cernescu’s notable Bulgarian productions of Hamlet and Macbeth are perhaps the most famous. And no doubt influenced Heiner Muller who was in Bulgaria in 1977, and has said it was there that he began Hamletmachine). Macbeth was seen in the light of tyrannical fascism, and of authoritarian power in general. Kott provided the modern paranoid Shakespeare. That political violence is crystalized on stage in the overdetermined metaphors, and that history is that which cannot be stepped away from. Kott’s influence was huge in the sixties and seventies; from Peter Brook to Peter Zadak and Peter Stein, and Giorgio Strehler. In all there was suddenly the sense of de-Victorianizing Shakespeare. He in one way became Elizabethan again.

Hamlet Machine (Heiner Muller). la Teatrul National Iasi,. Giorgos Zamboulakis dr. 2013.

The idea of setting, though, is something I think needs to be tweezed apart a bit more. Shakespeare wrote Julius Caesar for example, and the setting is, in fact, at least nominally real. It is clear that this is meant to inform the audience’s perception of dramatic structures within that play. And yet, this is not a real Rome. Not in the sense of historical detail. But is anything ever meant to be realistic? Everything is partly making use of conventions of history and memory, and partly, intentionally, creating something else personal. The character of Caesar is both Shakespeare’s vision of at least a part of what he felt was a truth about Caesar. It is also unavoidably personal. It is an assemblage of historical truisms, and that contemporary quality to Shakespeare’s Rome constitutes a commentary of sorts.

The poet John Berryman is among the more astute Shakespeare scholars. He points out a line of Lady Macbeth, to her husband…

what thou wouldst highly

That wouldst thou holily

This is a kind of strange almost surreal syntax that Shakespeare used several times in this play (act 1 scene 2 in its entirety). It is a play of exaggerated language, even for Shakespeare. It is unnatural. As Berryman says, nobody has ever spoken like this.

Paloma Varga Weisz

“Macbeth is announced, at his first coming, by a military drum; it is open, public; he is a hero, a man with a name. At his second coming he is announced by the pricking of a witch’s thumbs, his resort is secret, and he comes not as a hero but as a tyrant; we must imagine as suggested also a terrible diminishment, from the booming of a drum to a slight physical manifestation, corresponding to a removal of the real scene from the objective world to the subjective. But this is not all, or even the main thing. It is as “Macbeth” that he first comes, to be saluted by three prophetic titles. It is with his three titles that he next comes, but not called by them, or even described as a man, but only as “something wicked.” His nature has changed—not his characteristics merely, but his essential nature. He has become, perhaps, a demon; and the form, and sound, and allusive value of the couplet help to suggest this as no paraphrase could do.”

John Berryman

From a real objective world to a subjective. This is a really astute observation. But it is important to examine the way in which he appears those first two times. The public is off-stage. Whatever the public might mean in this dark cursed world. In the film, of course, he appears at his son’s funeral. Except there is no son in the play. There is the implication, perhaps, that a child was lost to Lady Macbeth. She says “I have given suck”. The ambiguity feels haunting. But Shakespeare chose not to tell us definitively. And he chose to so in his shortest tragedy.

The significant aspect of this discussion has to do with the meaning that is imprinted on this film by the social forces of its production. The loss of overall cultural meaning, or rather perhaps cultural differentiation, is exactly embedded in this question. In other words, this is a movie adaptation of a Shakespeare play, and it is asking the audience to engage with Shakespeare as if it were a special episode of The Good Wife or The Affair. It is additionally, by virtue of its *movie-ness*, erasing these tiers or steps of meaning. By which I mean the profound density of the language firstly. William Empson pointed out the exaggerated vowel sounds that grow as darkness comes, as the Rooks “brought forth/The secret’st man of blood”, and light itself is thickening. Looking out the window to check on the advancing dusk. For Banquo was soon to be killed. But after dark.

“The ambiguity of Macbeth’s nature is perhaps the play’s major subject. This is the shortest of Shakespeare’s tragedies; it is barely half the length of Hamlet. It follows that the intellectual and artistic work that is being done in the play is being done, even more than is the case in the other tragedies, in terms not of statement but of suggestiveness.”

John Berryman

Jose Vargas Croft

Adorno wrote….“The process, which in each artwork takes objective shape, is opposed to its fixation as something to point to, and dissolves back whence it came. Artworks themselves destroy the claim to objectivation that they raise. This is a measure of the profundity with which illusion suffuses artworks, even the non representational ones. The truth of artworks depends on whether they succeed at absorbing into their immanent necessity what is not identical with the concept, what is according to that concept accidental.”

The artwork’s claims to substance, then, are increasingly illusory. What it says it is and what it really is: this is partly the maddeningly opaque quality of cultural product in an era of mass saturated kitsch. Kurzel’s film of a Shakespeare play is a movie first, and it is an action movie first and a romance first, and a prestige commonwealth movie first. It is everything else first. We never get to the play, for the play must be a negation of that semblance, as Muller did with Hamlet in Hamletmachine. Now of course there are countless terrible versions of fake Muller, too. But to find the play, to experience the play in a film, the film must destroy itself. And Kurzel’s Game of Thrones iteration of Shakespeare, which is what G of T is anyway, a pretend training wheels Shakespeare, is far better on almost every level than, say, Julie Taymor. I remember watching, I think, Arthur Lee and Love and my friend said, oh black guys imitating white guys imitating black guys. (Love was really rather good by the by). I digress. This is the conundrum of such projects. In one sense there is a desire for accurate and concrete (even) performances of psychic states — psychological realism, or authenticity. Even in films and theatre projects that consciously strive for an avant-garde sensibility. But this is fueled by twin tributaries; method acting by way, these days, of the Drama Center in London it seems, and the residual effects of a privileging of virtuosity. There are technical aspects (hand held camera) that become structural in a sense because they mediate the performances. The opening scene of the child’s funeral is an example that simply reads like an episode of the History Channel’s Vikings. One either caters to the consensus in terms of aesthetic forms, or you find a way to negate them.

Korol Lir (King Lear), Grigori Kozintsev , dr. 1971

Adorno said the artwork must transcend its concept in order to fulfill it. And all art, all of it contains a latent relationship to the duplication of reality — in a sense, to the outside world. All art is the ghost of itself.

Polanski’s 1971 film version of Macbeth is rather neglected. It is interesting in relation to Hamletmachine and Muller, for both, for obviously different reasons, accessed Manson. Polanski I am pretty sure has never made a more nihilistic film, and one so misanthropic. It is a strangely anti intellectual treatment of the play, and given the grandeur in places of the language, it is an oddly unsettling experience (not in a good way). It is also interesting that 1971 was the year of the Soviet film production of Lear, Korol Lir, directed by Grigori Kozintsev and starring the remarkable Juri Jarvet. Now even more than the Welles, possibly, the Soviet Lear is the completion of Adorno’s admonition, the killing of the cinema, and the resurrection of a place both impossible, subjective, and purely nightmarish. Kozintsev spent years in preparation for both his 1964 film version of Hamlet, and for the even more profound 71 version of King Lear. Shot in Estonia, there is nothing quite realistic in any of it. And one might ask in what ways do both Polanski, finally, and Kurzel fail, while Kozintsev does not? The Welles is a bit of both, but one in which something significant occurs, and so a success of sorts, whatever that means. And I think it means to at least produce an awareness of one’s own limitations. The 1965 Welles Shakespeare, Chimes at Midnight, is however probably the greatest filmed Shakespeare. Perhaps it is just awareness. Polanski’s film is at least that. And it feels very personal. The Welles is irresistible because Welles was such an intuitive genius of cinema. It is a bit reminiscent of watching Que Viva Mexico, where at a certain point the viewer no longer cares if the narrative makes any sense at all, on a superficial level, because the deeper meanings are so rich and mysterious. It is also just the sense of taste that you see in every frame of Welles. This is just that ineffable mise en scene of great directors. And it is not frames in isolation, it is the accruing of space and duration and sound. It is also that Chimes at Midnight was made on a shoestring in Europe with a multi lingual cast and dubbed later (Welles did several of the voices). In that sense it is anti-cinema, it is a replacing of perceived bourgeois virtues by both a technical and a conceptual negation.

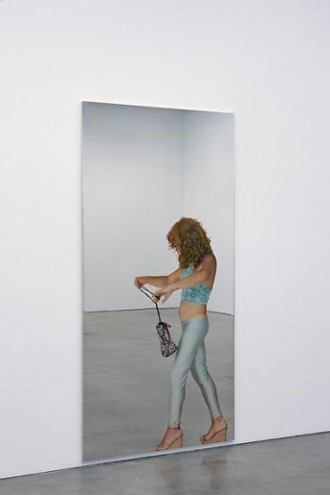

Michelangelo Pistoletto

The cost of major studio financed film today precludes making anything like the Soviet era Lear.

Artworks are caught in a situation of the impossible, which as Adorno knew, meant that even in the conscious destruction of semblance, the artwork was guilty of the semblance of that action which destroyed. And complete eradication of semblance would kill off the very premise of the artwork itself. In other words, the appearance of what is meant, the conceptual meaning, often hides the deeper meaning — the integration of concepts into the artwork, into the whole, as a whole, also challenge or question the synthetic conceptual totality. But this is where the legacy of instrumental thinking enters; for the mimetic particular can open (or unseal as Adorno put it) the non conceptual truth of art. The relevance today is that the hegemonic power of marketing concepts and expression, the marketed semblance of the work is immunized, in a sense, to the tensions of those factors that unseal the non conceptual. In other words the non conceptual is no longer always the non conceptual.

“How can making bring into appearance what is not the result of making; how can what according to its own concept is not true nevertheless be true? This is conceivable only if content is distinct from semblance, through the form of that semblance. Central to aesthetics therefore is the redemption of semblance; and the emphatic right of art, the legitimation of its truth, depends on this redemption?”

Adorno

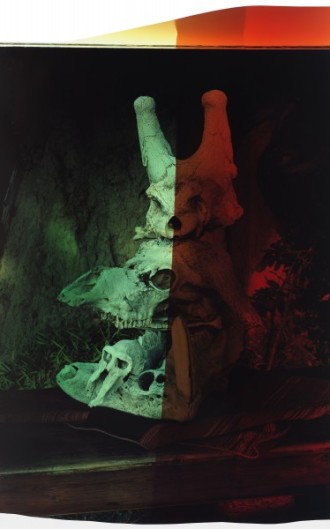

Unknown artist. 17th century, England.

In the case of historical texts, the material is mediated or brought into being through a prism of contemporary materiality, and subjectivity, which itself is subject to the laws of the conceptual. Ulrich Plass points out that in this context allegory is the ‘noticed’ semblance character of meaning. Or the *as if* quality of poetic logic. This is the start of the complexity that narrative forms bring to this discussion. For we *read* into our experience. This is also something I suspect is made even more complex by the historic moment for cinema, where so much of life is shaped by screen language and reading. Adorno added that the radicalism with which the technical work of art destroyed illusion (aesthetic illusion) makes illusion responsible for the technical work of art. I have quoted Robert Hullot-Kentor on this before:

“Art is semblance that, by its completion, causes semblance to collapse.”

Bela Tarr shot an anti Macbeth, too, in 1982. Filmed in two long takes it is Shakespeare as Sarah Kane or Beckett. What one finally makes of it is probably still open to debate. I am not sure claustrophobia is the right vehicle for Shakespeare, but it is unmistakably a work of integrity.

“Joseph Papp’s free performances of Shakespeare {1954} in the streets of New York were,

therefore, a deeply political act. They were Papp’s way of joining Shakespeare in the fight

against powers which impoverish minds, block development and destroy life, and which

remain unresisted largely because unrecognized. Shakespeare and Papp understood art to

be the activity through which such recognition and resistance become possible. Dedicated

to, and inspired by the liberating power of Shakespeare’s works, Papp’s performances,

improvised in the street or Central Park, were probably more truly Shakespearean than

any number of pedantically and superficially faithful renderings of the plays mounted in

the various meticulously reconstructed modern versions of the Globe.”

L.J. Bogoeva-Sedlar

Macbeth (1982) Bela Tarr, dr.

Sedlar’s paper, for the University of Belgrade, is an insightful look at Shakespeare, today. She quotes Peter Sellars who created a three actor version of Macbeth: “Because I wanted to get another way of reading the text. I wanted to remove the received associations that we have of that play − of all of the Shakespeare plays. You see, I’ve never really believed in plot that firmly because a play is about content. It’s not about the story. Plot is the hook on which the playwright hangs what interests him. By entirely removing the plot I wanted to treat the play line by line, literally, for “what does it mean?” In America we are totally at the mercy of the plot. Everything is the synopsis.” This is all sort of couched in the context of Ted Hughes massive book on Shakespeare, The Goddess of Complete Being. Whatever one accepts in Hughes, and I accept a good deal of it, really, even if I disagree with many of the assumptions, it does then touch on something resonant of the social trauma of Shakespeare’s time. The reformation, the misogynist war on the feminine, and the Dionysian, by Puritanism, and the patriarchal violence expressed in class domination and hierarchical society altogether.

Speaking of Francis Bacon’s work, Sedlar writes;

“He was so shocked to realize that Poussin’s painting was accepted by others as a well executed illustration of history, and

not its challenge, that he decided to make its central meaning (the unheeded scream, the

failure of the feminine to protect young life from the political abuses and violence of

patriarchy), disturbingly visible and audible in his own art.”

Cildo Meireles (HangarBicocca, Milano)

Shakespeare is very violent. But the nature of that violence is important to understand. When Adorno writes of the non-conceptual embedded within semblance, it echoes what Hughes calls the mythic layer beneath the narrative. All stories are crime stories. Each is an investigation of a crime. In Kafka’s The Trial, the plaintiff is civilization — but there is no public defender. The rejection of the Dionysian, or the feminine, the sex negative Puritanical patriarchal and hierachical system of coercion that established itself in the West, carries through with the hysterical anti-communism of the U.S. over the last eighty years. How can one not see the violence of U.S. military aggressions in Libya, Iraq, central America, and the proxy wars in Ukraine and Yemen or the various covert wars on Venezuela and disconnect this from the cultural realm? The figures of Pinochet, or Netanyahu, or Franco and Hitler and Papa Doc are all Shakespearean studies of crime. The police violence against black communities in the U.S., the FBI war on the Panthers, the vast American gulag prison system — cannot be processed as separate from civilizational patriarchal white crime. Wall Street and the CIA are Shakespearean plots. The only depiction in film of Wall Street violence is couched in sit com form in The Big Short. Where is the mythic level in that?

“… promoting the rational, analytical verbal formulation of life, in other words lifting the left side into dominance literally by suppressing the right, seems desirable in some situations. But where it becomes habitual, it removes the individual form the ‘inner life’ of the right side, which produces the sensation of living removed from oneself. Not only removed from oneself, but from the real world also, and living in a prison of sorts, since the left side screens out direct experience, establishing its verbal ‘system’ as a hard ego of repetitive, tested routines, defensive against the chaos of real things. …Metaphor is a sudden flinging open of the door into the world of the right side, the world where the animal is not separated from either the spirit or the real world or itself.”

Ted Hughes

Franky Verdickt, photography.

The wholesale collective violence against animals in factory farming is, alone, testimony to the macabre sadistic corruption of human consciousness today. The constant conflating of communism and fascism is more testimony. For what are these political systems based on? Never mind the opinions on particular cases, one is predicated upon exploitation and is anti-life, and one is predicated on the removal of exploitation and on sharing.

“Lenin always said revolution comes from the provinces, and women are the provinces of men.”

Heiner Muller

William Empson touches on several things in his readings of Macbeth that are relevant to filming this play. Empson argued that Macbeth came before Lear, and it’s hard to argue with that if you read them again, in that order. And the prevailing wisdom has Shakespeare suffering some kind of breakdown after Lear. Empson makes a wonderful observation that after the breakdown, Shakespeare never again was one with his characters, but remained above them, and Antony and Cleopatra certainly supports that argument. But the darkness of Macbeth, and the rapidity with which the plot advances, both speak to the sense of ‘not seeing clearly’, of acting without due reflection. Now Shakespeare may have added stuff to please King James, but how much he may have hurriedly cut this play is unknown. In any event, the character Macbeth wants the murderous acts done, without having to feel too much responsible for them. This is a strange crime drama, really.

Empson writes…

“Thou wouldst be great,

Art not without ambition, but without

The illness should attend it; what thou wouldst highly

That thou wouldst holily”

and so on, is not meant merely as obvious moral paradox from

the author but as real moral blame from the deluded speaker; a

man should be ambitious and should have the “illness” required

for success in that line of effort; it is good to will highly, and

slavish to will “holily”. The inversion of moral values is sketched

as an actual system of belief, and given strength by being tied to

the supreme virtue of courage. Of course it is presented as both

wicked and fallacious, but also as a thing that some people feel.”

Arno Rink

However one interprets Shakespeare’s intentions in this, his shortest tragedy, the point here, in light of this current film of the play, is that this is a massively complex text. Terry Eagleton argued at one point for the feminine power in this play, and I think that is, in another way, what Hughes is saying. The Cromwell/Puritan war on the Madonna of Catholicism (per Hughes) is the backdrop against which the somewhat reluctant Macbeth and Lady Macbeth act out the violence that such systems demand. It is a play, it has always seemed to me, about the idea of esteem and power, but also of obligatory sin. Transgression cannot be escaped. And every character in the play seems to know this. There is a pious nastiness at the heart of hierarchical social orders, where domination and oppression and violence are anticipated as routine, and where war is constant. The witches are a partly speaking from the off stage. For their language is unnatural, and they awaken Macbeth to the possibilities his situation allows. Macbeth has never seemed to me to be a great warrior, though clearly an efficient one. A calculating one, and an opportunistic one. But he is also a little man, a resentful one, and an unhappy one. It is a play of little literal clarity (Empson called Dover Wilson’s analysis something closer to Racine, because in Shakespeare there is a fog, and filthy air) and the suggestion is, finally, that one’s motivations for personal gain are always taking place in filthy air, and are part of a diseased social order.

This is a film of far greater skill than Taymor’s Shakespeare, or god forbid Baz Lurhmann, but there is nothing in it that suggests a contemporary critique of any sort. It is comfortable being a Hollywood film. The meta transgressive is missing. The meta reading is white liberal, and it is good taste, and the only controversy might be in all those battle slow motion exploding blood packets. It is Shakespeare that neutralizes the tragic and reinforces the system that financed it.

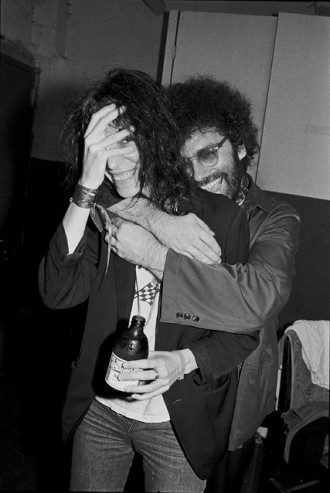

Terry Ork and Patti Smith, NYC 1977.

A final note on a topic I touched on before, briefly. My old friend the late Terry Ork (aka Terry Collins, Bill Collins, Noah Forde, Bill Terry) was in the media again. Two or three times in fact. The NY Times had a piece on Ork Records, some box set coming out of old recordings found in storage that were previously unreleased. Richard Hell, he with a new book coming out, was interviewed and referred to Ork as shady and a dilettante. There was another piece in the Guardian I think on the 70s music scene at CBGBs, and Ork was mentioned and then the actor who plays Ork in some misguided film about that era and the club itself was interviewed. And in all of this, taken together, nothing of the Terry Ork I knew could be found. Firstly, Hell should not be calling anyone a dilettante. Second, Ork was as literate as anyone I’ve ever met. I lived in a loft on East Broadway in Chinatown with Ork for around five years, but I knew him closely for over a decade. Terry was certainly flawed, and tragic almost but he was a radical, a visionary in many respects, and he taught me as much as anyone ever has. He was there when my son was born, and was hugely supportive to all of us — and while it was in his DNA to finally betray everyone, I find it hard to think badly of him. Before NYC he worked on the Eldridge Cleaver presidential campaign, and tirelessly against the Vietnam war. He worked for Warhol and invented (with Gerard Malanga) Interview Magazine for Andy. He had a remarkable library, the likes of which I am sure I will never see again. He knew rare books, and cinema (he had a world class collection of film stills) and when the feds stopped him at LAX and took him to Terminal Island (he did a year I believe for fraud) he asked only for a copy of Adorno’s Minima Moralia. Ork invented CBGBs too, but that was an era in which I began to drift away. I found Tom Verlaine and Hell and the rest all very tedious and the music was even more tedious. But the point is that Ork turned a crappy Bowery biker bar into the mecca of a certain music scene in under a year. That he is to be remembered for that alone is rather sad, though, because he was a very genuinely fine poet (who never let anyone read his work) and he should have written more on film then he did, because his knowledge was vast. Nobody who knew him well ever doubted his brilliance. But the lesson here is that history gets written, apparently, by suburban white kids whose education is tirelessly reading VICE and GAWKER.

It is disturbing to see the process first hand, intimately — the historical record will end up bearing no relationship to fact. In that sense Ork’s story is not totally unlike that found in one of his favorite films, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. Print the legend. Or, just print the pseudo legend. Or just make it up.

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962). John Ford, dr.

“Macbeth has never seemed to me to be a great warrior, though clearly an efficient one. A calculating one, and an opportunistic one. But he is also a little man, a resentful one, and an unhappy one. It is a play of little literal clarity (Empson called Dover Wilson’s analysis something closer to Racine, because in Shakespeare there is a fog, and filthy air) and the suggestion is, finally, that one’s motivations for personal gain are always taking place in filthy air, and are part of a diseased social order.”

I have speculated that the reason for this is because Macbeth never actually kills anyone in the play save Duncan. I have posited that Macbeth doesn’t even kill Macdonwald, rather he finds his corpse and dismembers it it the most brutal way. He seems to me to always be living out a fantasy, and we know from modern serial killers that disfiguring a body is oftentimes a way of living out fantasies, a way for disempowered people to finally get their way.

@magna: terrific — I’ll buy that, and its odd that when I directed the play I had a wonderful actor, but a very small man, slight. Intense. That always seemed perfect to me. I can’t even really tell you why. In any event, as I say, I had the first witches scene at the end, with macbeth doing the voices of the witches…which would segue with your idea rather perfectly. There is, I think, a quality of hallucination in macbeth — and the play always works best when it is performed less rationally.