Louise Nevelson

“The hunter could have been the first ‘to tell a story’

because only hunters knew how to read a coherent sequence of events from the silent

(though not imperceptible) signs left by their prey.”

Carlo Ginzburg

“It is now necessary to ask ourselves a question: Why, in order to define the

Nazi régime, should the argument regarding the one-party dictatorship be

more valid than that of racial and eugenic ideology and practice? It is precisely

from this sphere that the central categories and key terminology of the Nazi

discourse derived. This is the case with Rassenhygiene, which is essentially

the German translation of eugenics, the new science invented in England and

successfully exported to the United States.”

Dominico Losurdo

“Horkheimer and Adorno consider the stages that paved the way to Nazism

to be not only the violence perpetrated by the great Western powers against

the colonial peoples, but also the violence perpetrated, in the very heart of

the capitalistic metropolis, against the poor and outcasts locked in the

workhouses.”

Dominico Losurdo

“Ur-Fascism grows up and seeks for consensus by exploiting and exacerbating the natural fear of difference. The first appeal of a fascist or prematurely fascist movement is an appeal against the intruders. Thus UrFascism is racist by definition.”

Umberto Eco

“[w]e will never have a complete definition of fascism, because it is in constant motion, showing a new face to fit any particular set of problems that arise to threaten the predominance of the traditionalist, capitalist ruling class.”

George Jackson

The end of this year seems marked by a particular coalescing of several very reactionary trends in the U.S., and to a lesser degree in Europe (though Europe now has several of their own, though different, reactionary themes surfacing). But all of it is related.

One of the hallmarks of fascist thinking is a fusing of bigotries. In the U.S. today, there is the surge in Islamophobic rhetoric, accompanied by a resurfacing of antisemitism, and also with a cagey kind of new Colonial branding (see Bacardi graphic novel below). The antisemitism is representative of something else, though, too. Mary Ann Henderson and Brian Platt had a piece recently at Counterpunch that touched on a side bar issue to this; where they write: “The war on Christmas is more than a tinfoil hat conspiracy theory, it is a gateway into a conservative politics that exalts capitalism, racism, and nativism while attacking the Left.” Now, before I get into their cogent analysis of the origins of this veiled antisemitism, I wanted to look at the peripheral ideological elements that serve to link Colonial nostalgia, racism, white privilege, and Imperialist war, militarism, and the re-emerging of pathological paranoia. A paranoia that is rooted in the hyper regressive state of ‘forgetting’ today in the West.

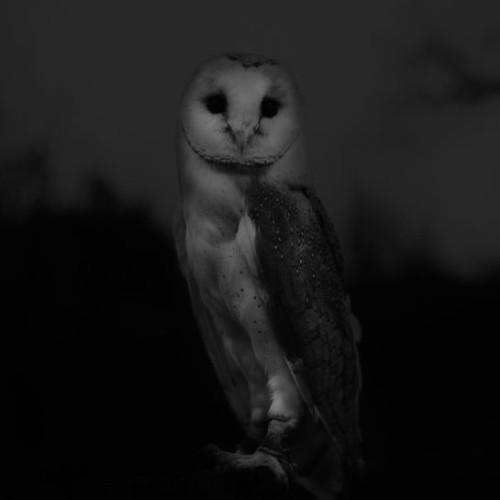

Sophy Rickett, photography.

The vulgarity of FOX News and Roger Ailes, Murdoch, and for his part, Trump, is one that is not hugely different than that which Henry Ford promoted back in the 1920’s. Henderson and Platt give a nice summation of Ford’s antisemitism, which was directly targeting Bolshevism and unionizing domestically. In the 30s, however, the left was still quite vibrant and strong in the U.S. and trade unionism certainly was, and Ford made little real headway with his tract “The International Jew”, a book miraculously still in print. Today however, the FOX News racists have a huge and growing audience of mostly white lower middle class and underclass viewers. Ford, and later Baptist Preacher Gerald Winrod, in the late 20s, also disseminated The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, (a fictitious text written in Russia, in 1902) touring the country handing out free copies. This was the great depression in the U.S. and there was a sizable population in dire conditions, and looking for scapegoats. The unionized Left of the 30s and 40s however were well organized and with the New Deal, the workers in the U.S. formed a strong movement. What I want to look at in all this, though, were the earlier manifestations of antisemitism, and then the links to Colonialism, both aesthetically, and culturally, and also with the anti Muslim hysteria of the moment. And then the effects on aesthetics and culture overall today.

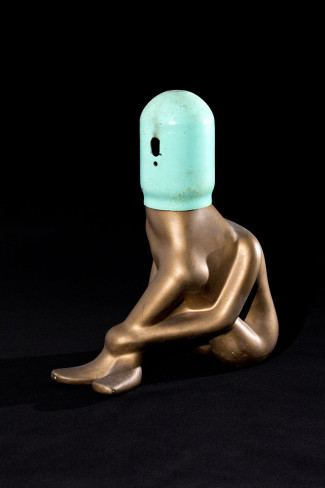

Valerie Blass

Islam hating is the new antisemitism, and its not as if antisemitism ever went away. But with the ratcheting up of Israeli brutality, and open ethnic cleansing, and with virulent hate speech from Israel’s right wing leaders, the resurgent antisemitism (borrowing tropes strategically from Henry Ford and others) has found a new source of material handed to them by Netanyahu and Likud. The fact that Israel is at heart a colonial project, an occupying force, is, in reality, not a problem for a great many American supporters. For white America remains crypto-colonialist. They will always identify with the colonizer. So there is a fundamental contradiction in this; a support for Zionist occupation, while still holding onto a basic antisemitic prejudice. There is certainly an increased criticism of Israel, and the BDS movement, but this often marks, in places at least, the surfacing of latent antisemitism through a conflating of Zionist and Jewish. This also relates somewhat to Adorno’s notion of secondary antisemitism, and Zygmunt Bauman’s ideas regarding the projecting of taboo impulses onto the Jew, and thereby creating this ambivalence made up of equal parts admiration and denigration. Also, part of viewing ‘Jews” as the ‘colonizers of today’ deflects attention away from the crimes of former colonial powers. Just as denying Zionist colonialism serves the same purpose, really. And in a way this is what makes the U.S. Imperialist factor such a source of confusion. Remember too, that the neo-liberal agenda in the U.S., that ascended to power in the 80s, then in the 90s took over Israeli politics. Zionism was always colonial but not always neo-liberal. The even more intriguing aspect of this new artificial memory of the white bourgeoisie is that it is coupled to a stealth reactionary and racist rhetoric that also comes from the pseudo left (Zizek comes to mind, firstly). For Zizek manages to smuggle into most of his articles or interviews an aesthetic, and usually a grammar and vocabulary redolent of those early Henry Ford/Gerald Winrod tracts, and which later found expression in right wing televangelists like Billy Graham, as well as libertarians of the Alex Jones fringe variety. Zizek is not all that far from Alex Jones in certain of his style codes and dog whistles. But Zizek’s followers (and one need only read comment threads for any of his articles) justify anything he says because they construct elaborate (as needed) houses of logic to account for it. The Alex Jones side of this, a crude purveyor of ZOG style rhetoric, which as his popularity grew he has toned down, is related to all anti-communist libertarianism. But Jones also pulls jargon and style cues from white Aryan survivalists, and the Klan. Zizek appeals to University students by trotting out Lacan and and calling himself a Marxist and a leftist, though there is scant evidence in any of his writings that this is true. But he also is canny enough to talk about movies and pop culture, embrace Pussy Riot and position himself on the U.S./NATO side of the Russia question.

Post WW2 antisemitism migrated to the borders, the fringe, where white survivalists employed Nazi rhetoric and symbols, but in and to a different means and end. Jones comes out of that sensibility. Whenever one hears Federal Reserve and tax freedom, you can be pretty certain that an antisemitic article is coming. But there is a certain tone, and a certain way of framing enemies that Zizek shares with the fringe antisemites and that have come down from the Henry Ford pamphlets of the early 20s. There is a subtle formulating of *hidden* enemies. Zizek is more sophisticated in a sense if only because one has to pass through two or three doors to get the inner secret, which usually houses a threat of some sort, and by extension an enemy. And his message is often one critical of softness. One must make hard decisions, what is needed is a Thatcher of the left, or his recent analysis of immigrants coming to Europe wherein such immigrants pose a threat to European way of life (sic). Let me quote Zizek here…

“We should avoid getting trapped in the liberal self-interrogation, ‘How much tolerance can we afford?’ Should we tolerate migrants who prevent their children going to state schools; who force their women to dress and behave in a certain way; who arrange their children’s marriages; who discriminate against homosexuals? We can never be tolerant enough, or we are always already too tolerant.”

Sounds far more like European right wing parties than anything else.

Umberto Eco, in his essay Ur-Fascism points to fascist movements usually being syncrenistic. Meaning, they tolerate contradictions. The enemy, through rhetorical shifts of focus is both too weak and too powerful. Too backward and too cunning. But this also means the combining of traditionalist material and literature in ways that create a new way of pointing to some primeval truth. And that there must also be *plot*.

Eco writes:

“Thus at the root of the Ur-Fascist psychology there is the obsession with a plot,

possibly an international one. The followers must feel besieged. The easiest way to solve

the plot is the appeal to xenophobia.”

But the plot usually also comes from the inside. As Eco says, Jews traditionally are useful targets because they are both inside and outside. Today, there seems to be a fusion between Jew and Muslim. However this new fascism develops, however, it will contain new aesthetic forms.

Otto Dix (Dr. Mayer-Hermann. 1926).

The Alex Jones conspiracy fringe also borrows heavily from Lyndon LaRouche and his group. LaRouche is, in one sense, the ‘reactionary racist’ link to the left, for LaRouche was active with both the Spartacists and Gerry Healy, and various Trotskyist organizations in his early days. But LaRouche also exemplifies that certain white American male of the mid 20th century. He is not all that different in the end from L.Ron Hubbard, if for no other reason than cultic personality traits and personal delusions. They are anti institutional, except when it is useful, anti government, anti communist (mostly), and with barely camouflaged racist beliefs. LaRouche at bottom, though, is a fascist. He and his followers hate banks (Jews), environmentalists and leftists (notwithstanding his early years with Trotskysts), and organized labor. There are dog whistle attacks on queer culture, and a clear set of symbols and rhetoric that sounds curiously like the Freemasons, which is also what much of Alex Jones sounds like. In the case of LaRouche it is often hard to know exactly where he stands, I suspect, because opportunism has been the overriding ideological imperative. What is most unsettling in all this, from Jones to Zizek to LaRouche to publications such as Pulse (Pulse media) or organizations like MoveOn, is that even a blind squirrel gathers some nuts. A broke watch is right twice a day, etc. So, even Jones is right about certain things, and those things are often stuff that is covered up by mainstream media. The fact that his conclusions are ALWAYS wrong soon ceases to be the point to many of his followers. For the same reason many Scientologists continue on with the Church (sic) even though, really, they know its a lot of sci-fi mumbo jumbo quack technological nonsense. Across all of this is a strange confluence of the half educated, the electronically literate, but sub literate in all other things, and the paranoid. One does not subscribe to Alex Jones or LaRouche if one is not paranoid.

In the new pseudo left, from the likes of Charles Davis (shockingly published by Counterpunch this last month) or Idrees Ahmad, or Molly Crabapple, Laurie Penny, or Zizek, there is, lurking right beneath the surface, a kind of hostility to the masses. A subtle elitism, and white privilege. It consciously looks to sound populist and brands itself with an aesthetics of *unpretension*, even while promoting with the other hand a very clear aura of cool (more later on this specific sub phylum of cool). Cool but not pretentious. That is the semiotic register for all this. But this targets the University educated, who, even if some of them think Jones is onto something, will still not take him completely seriously. They ‘will’ take Zizek or Charles Davis seriously, though, and Crabapple. For they represent the correct class. It is a sort of fraternity boy real-politik; meaning they are leveraging that posture of instrumental no-nonsense rationality. This also includes TV personalities like Bill Maher. But I will come back to this…

Julia Kunn

To return to antisemitism, specifically, for a moment, as it interfaces with Islamaphobia today, the LaRouche people are also harkening back to a kind of neo-Puritan sensibility; they decry hedonism and are virulently anti drug. And in an odd way, LaRouche is the third cousin to Walt Disney and Hubbard. White men, non mainstream really, reactionary and anti union, and strong believers in science (LaRouche is pro nuclear energy), self made (by their definition, anyway), pro-Industry and pro-progress, and pro White. They are homophobic, antisemitic, and anti communist. Those are the base markers in play. In the 60s, they hated the hippies and counter culture, even while taking diverse stances on the war. And again, today, Zizek cleverly always finds a way to express his fondness for rank arch conservatives and outright racists (Houellebecq for example, or Thatcher). The pretense to dialectical cleverness is in reality a one dimensional defense of authoritarian neo-police state Imperialism. And that includes racism, antisemitism, and Islamophobia. And it is more than a little curious that the faux left today can defend a Houllebecq, and not see any problem because they are so liberal in their self branded tolerance and progressiveness. There is throughout this grouping, consistently, a focused soft criticism of U.S. Imperialism, in inverse proportion to the exaggerated and blanket demonizing of Muslim *terrorists* or *dictators*. Except of course there is little historical perspective, unsurprisingly, on Western colonialism. And when it is there, again, there is a strange absence of conviction about the crimes of Imperialism. And as always there is a tacit anti Russian bias.

Andre Vltchek correctly writes:

“During the Second World War, the Soviet people, mainly Russians, sacrificed at least 25 million men, women and children, in the end defeating Nazism. No other country in modern history has undergone more.

Right after that victory, Russia, alongside China and later Cuba, embarked on the most awesome and noble project of all times: the systematic dismantling of Western colonialism. All over the world oppressed masses stood up against European and North American imperialist barbarity, and it was the Soviet Union that was ready to give them a beacon of hope, as well as substantial financial, ideological and military support.

As one oppressed and ruined nation after another was gaining independence, hatred against the Soviet Union and the Russian people was growing in virtually all the capitals of the Western world. After all, the looting of non-white continents was considered a natural right of the “civilized world”.

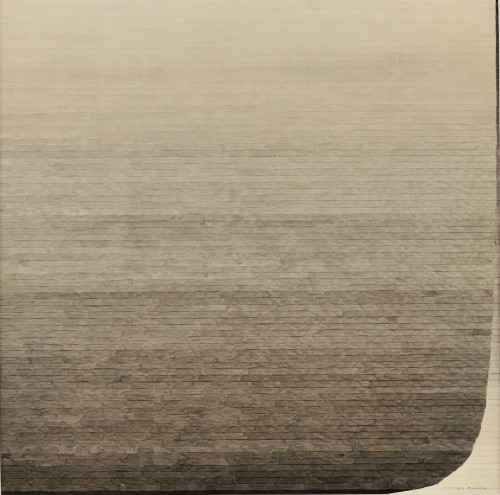

Nasareen Mohamedi

You cannot be even nominally leftist if you uncritically embrace Pussy Riot. If ever there was a litmus test, they are it. And yet, Zizek will continue to find op ed space in countless *left* journals and on countless left panels. And he will be asked to write the introduction to books by radicals, communists, and Marxists (see his intro to the works of Mao). There is a real question here as to how this happens. What are, exactly, the mechanisms by which this happens? Well, a good example is to be found at Salon (quelle surprise) in the person of Andrew O’Hehir. He quotes Zizek extensively, attacks Vltchek and Chomsky and what he calls the *desiccated left*.

Allow me to quote:

“Philosopher Slavoj Žižek does not mention Cohen or Chomsky by name in his provocative essay on the Ukraine crisis and the Stalinist roots of Putin’s neo-nationalism, published in May in the London Review of Books. But Žižek’s target is very much the “so-called anti-imperialism” of the desiccated Western left, blinded and choked by the ideological dust storms of the Cold War.”

It is worth reading the entire article because it is so representative of the pro Imperialist red bashing pseudo left today. Except, to be clear, O’Hehir is not a leftist. Not even vaguely. He is a reactionary hipster white man who is of a generation more craven than any in memory for approval by the status quo. He has a career after all. O’Hehir writes for Salon. (Pause for reflection). His bio tells us he has also written for The New York Times, Washington Post, and Hollywood Reporter. Essentially he is a film reviewer. It is therefore hardly surprising that his politics are standard mainstream media hipster white pro-Imperialist. One does not gain favor with the New York Times or Salon by expressing original or radical ideas. It is permissible, even encouraged I think, to criticize Obama (to some degree) and Bush and even Clinton. That speaks to his cynicism, and cynicism, as Adorno put it, is only another mode of conformity.

Assyrian relief from Nimrud, 728 BC.

Now since I began with a quite overview of Henry Ford’s vicious anti-semitism and anti-union policies, it is worth quoting O’Hehir again…

“The days of American specialness and bigness whether you’re talking about Cecil B. DeMille or Henry Ford or Gen. Douglas MacArthur are pretty much gone, and voting for Tweedledum or Tweedledee in November won’t bring them back.”

So to be clear, if you count Henry Ford and Douglas MacArthur among your heroes, you are deeply and teeth achingly reactionary. You are very close, ideologically, to Ronald Reagan. And even if you later write a bad review of a pro war film, that really doesn’t change your basic reactionary politics. O’Hehir has also written, in his review of Secretariat (the movie) how it is a paean to American whiteness and power. How, then, does this fit? Well, it does fit, because O’Hehir also, in that same review makes an offhand reference to the Watergate Hearings. It is the implication of belief in the system, the idea that the U.S. is flawed, but savable. It is, in fact, the standard liberal position. It fits perfectly with those who will vote for Hillary because Trump scares them. It fits perfectly with those who are outraged at police violence, but think there has been progress in race relations. This is that very specific but widely found American liberal who in the end will always side with Imperialism, will always believe in the system (because the system provides for their privilege) and who will always defend their privilege because they believe since they have the right to criticize movies, it proves America is a great democracy.

And as Robert Paxton, in his analysis of Fascism, points out; both conservatives and liberals will be the ‘coalition partners’ for any new fascism. Replacing brown shirts, black shirts and swastikas will be Stars & Stripes and Christian symbols, and Fourth of July parades. But the new fascists will also hold onto new ideas, marriage equality and multiculturalism. For in one sense, there is a kind of sleight of hand going on if all anyone pays attention to are the Christian fundamentalists and right wing of the Republican Party. Liberals will be willing partners and even a part of the driving force of this new fascism. (This is the problem with writers like Chris Hedges in fact). As living standards deteriorate for the majority of Americans, as the prison gulag and police grow in power, as whistle blowers are increasingly punished and as threats to U.S. currency grow — conditions are perfect for a new American fascism.

Koji Enokura

“In ancient Greece, the historian’s autopsia, or direct visual experience

of an event, was conveyed by stylistic “vividness”. This is a far cry from

what we are used to call “evidence”, which is invariably based on an act

of inference. Historians (like judges or policemen) make more or less

reasonable inferences about events they did not witness, relying upon

evidence as diverse as newspaper articles, fragments of pottery or cigarette

butts. But notwithstanding the obvious differences, a certain continuity

between our present and antiquity is undeniable, since both our notion of

evidence and the Latin evidentia emerged in the sphere of rhetoric,

especially judicial.”

Carlo Ginzburg

Now, the 20th century evolution of fascist aesthetics is linked to the industrialization of thought. But allow me to digress a bit and try to explicate aspects of the evolution of this a bit, and to touch on a few other things. Ginzburg has a terrific essay on Sherlock Holmes and Freud. And he points to the simultaneous rise of police detective and art connoisseur (of the modernist era). But then Ginzburg touches on something I find articulates with amazing clarity many of my beliefs on mimesis, by way of Adorno, and on aesthetics generally. Ginzburg speaks of the hunters of antiquity, and …“In the course of endless pursuits hunters learned to construct the appearance and movements of an unseen quarry through its tracks – prints in soft ground, snapped twigs, droppings, snagged hairs or feathers, smells, puddles, threads of saliva. They learnt to sniff, to observe, to give meaning and context to the slightest trace.”This knowledge is passed down, one presumes, and it is likely, I think, that much early cave art is related to this knowledge. And that these bits of observational detail also leaped to large gestalt concepts having to do with tracking prey. Hunters as the first narrators. This is also an echo of Robert Bly’s ideas on ‘leaping poetry’. The concrete detail is linked, mysteriously, to something seemingly unrelated that is conceptually of another register altogether. Ginzburg then touches on early Mesopotamian divination; and again there is the close study of minute details. Bird droppings, hair, footprints…anything, and the difference is, of course, that here these skills are employed to divine the future.

Domenico Ghirlandaio (1488, detail from Adoration of the Magi. Self portrait?)

Pharaonic Egypt, too, clearly saw ritual readings of cuneiform writing, or pictographs, as having an intimate link with not just daily life, or even the future, but with the after life. So here there is analysis of clues, or symptoms eventually; diagnosis, medical prophecy. And at the same time, the establishment in a sense, for humans, of mimetic narratives. The invention of printing served to de-link a number of things that were occurring in oral traditions. For one, something reductive took place that changed the nature of mimetic engagement.

“Among the ‘conjectural’ disciplines one – philology, and particularly textual criticism -grew up to be, in some ways at least, atypical. Its objects were defined in the course of a drastic curtailing of what was seen to be relevant. This change within the discipline resulted from two significanturning points: the invention first of writing and then of printing. We know that textual criticism evolved after the first, with the writing down of the Homeric poems, and developed further after the second, when humanist scholars improved on the first hasty printed editions of the classics. First the elements related to voice and gesture were discarded as redundant; later the characteristics of handwriting were similarly set aside. The result has been a progressive dematerialisation, or refinement, of texts, a process in which the appeal of the original to our various senses, has been purged away.”

Carlo Ginzburg

Martin Parr, photography. (Epsom The Derby. 2004).

This probably has had even more long term affect than even Ginzburg allows. But the point here is that a desire for standardization, for scientific and rational categorization served to abandon certain kinds of narrative knowledge. As Ginzburg says; “Knowledge based on making individualising distinctions is always anthropocentric, ethnocentric, and liable to other specific bias.” And mimesis, the mimetic response is buried, consciously, in places less accessible, and less acceptable. But there was another shift, culturally, that reflected advances in standardization, in definitions of Nature and man; and this came about in the 18th century. From Ginzburg again:

“In England from about 1720 onwards, in the rest of Europe (with the Napoleonic

code) a century or so later, the emergence of capitalist relations of production led to a

transformation of the law, bringing it into line with new bourgeois concepts of

property, and introducing a greater number of punishable offences and punishment of

more severity. Class struggle was increasingly brought within the range of criminality,

and at the same time as a new prison system was built up, longer sentences were

imposed. But prison produces criminals. In France the number of further offences

was rising steadily from 1870, and towards the end of the century was about half of all

cases brought to trial.86 The problem of identifying previous offenders, which

developed in these years, was the bridgehead of a more or less conscious project of

keeping a complete and general check on the whole of society.”

And this sort of brings me back to the contemporary fascist aesthetics, and to the kind of denuded consciousness in huge chunks of the populace in the West. The growth and intractable quality of *identity* today was solidified in 18th and 19th century England and France (and one could and maybe should add Holland and Germany). And this can be traced back to the disproportionate trust in detail. Detail that was foregrounded through optical technology. And in a sense this was a collectively defensive phenomenon. There was a growing societal anxiety, among the ruling class, about control of the underclass. The whole was impossible, in a sense, but details afforded a psychological cushion. This also further entrenched the idea of the *expert*. The modern diviner of readings of normally insignificant detail.

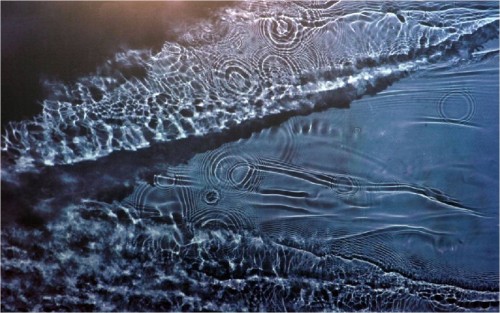

Susan Derges, photography.

Diagnosis, the interpretation of reality, and more, of individuals, based on clues became a psychological model for understanding of not just the disciplines of control and punishment, but of self. The controller better understood himself. The increasingly murky idea of the whole, the distrust of grand overviews, too, results in — at least in one respect — a reaction of and embrace of annulment. But side by side with this pseudo existential relativism came a doubling down on scientific (rational) definitions of individuality. And today, one might argue that this idea of *expert*, which has a foundational bias toward things technological, is a primary paradigm for Western society. Authority resides in the hands of experts. Historians are experts on history, Doctors are health experts, Generals are experts on war, and so on. Then the second tier expert is found in those who analyse data. The functionaries of the security state are now exalted as *experts* on things like facial recognition, or algorithms for spotting suspicious behavior, or of just computer code. And such people are oddly, usually anonymous. But their invisibility, their illegibility, goes a long way toward bridging that early structure of narrative knowledge. The expert is now like a bird dropping in one sense. Structurally they are studied by other experts, those technicians of accumulative information, themselves anonymous, who compile and parse apart the useful from the not useful. Society is entrusted to the hands of anonymous experts, who themselves are served by further anonymous experts, and then this diagnostic data is given a imprimatur of authority. Detail as was true in the 1700s is a clue, part of a puzzle of clues, and eventually the expert divines the meaning. People feel the familiarity of that outline, that shape of knowledge delivered mysteriously. They have no idea, themselves, of what bird droppings mean, or what those invisible techno bureaucrats are going on about — but it must be important. The previously unseen then takes on both an almost cultic importance, while at the same time forming a part of an accepted mosaic one might title ‘The Non Importance of Everything’.

The fascist sensibility of today finds cultural expression in a nostalgia for Colonialism. See this new graphic novel from Bacardi…

http://mashable.com/2014/08/07/bacardi-graphic-novel/#WKhMPjCbfkqX\

Joseph Cornell (frame enlargement from Rose Hobart).

one that has helped to increase the horror it supposedly condemned, thus falling into a tragic performative contradiction?” For the U.S. the general public today sees totalitarian in this vague way as a one party state, anti democratic, and hence dystopian and Orwellian. Images come to mind such as concentration camps and dark colorless tenement blocks. In other words, the U.S.S.R. The fact that the U.S. had their own concentration camps, for Japanese Americans, not to mention the *Indian schools* that followed on a genocide of native American tribes, passes unnoticed. But the real heart of societal violence is found in the surfacing of this nostalgia for colonialism. And it is hardly just Bacardi. Hollywood spews out a non-stop stream of Colonial narratives, usually featuring Victorian style codes and bathed in a nostalgic amber glow. But this is a fantasy Colonial era, and there is in reality precious little real narrative drama that involves the greater context or story of European occupation of Africa and Central America, or the middle east.

David Zink Yi, installation MUDAM, Luxembourg.

And that is what is most culturally interesting and most telling. The U.S. today never depicts itself as an occupier. It is a rescuer and a teacher. Maximillian Forte has a nice series on the U.S. military and how it markets itself over at Zero Anthropology. As Forge writes;

“The trick is to achieve superiority by being at once both engaged and removed. Being engaged shows you actively involved in the uplift and upkeep of other peoples’ lives, thus coming down the mountain to these peoples’ very low station in life. However, you need to stay removed–by never showing yourself being in need of others. Show photographs therefore of us feeding them, but avoid showing any photographs of us eating. Show us giving them water, but show us seemingly persisting in tough, arid climates, without ever so much as stopping to take a sip. Gods do not eat, drink, or bleed.”

Crimea, Soviet Union, 1950s.

The natural superiority of the white savoir. And this is the shape, the predicate, upon which most thinking stems when the topic is Imperialism. And of course, the idea of White superiority doesn’t end there. It extends to almost all formats and genres of storytelling, and even of thinking. Lena Dunham is a colonial savior, albeit a self ridiculing one (well, I’m not REALLY making fun of myself, that’s just my persona). There is another aspect to this manufactured Imperialist *real*; which contains both a revised history, but also must constantly reassure the present. Forte writes of military propaganda focused on showing soldiers babysitting locals in occupied countries, or playing hoop with some teenage boys, or singing with children etc. Even playing Santa Claus, although this set of photographic installments is more targeting the soldiers themselves. And this is important to understand because it goes a long way to understanding why Hollywood makes so many characters either ex military or currently military when so few of the actors, directors or producers themselves have ever been in the military.

Forte again:

“The function as intended may be for domestic recruitment purposes and internal morale boosting, but I would argue that there is another, broader, unspoken purpose, or perhaps more than one. One broader purpose, rooted in the official one above, is to stabilize and pacify emotions around the military and war. To do so, one has to create an unreality, a virtual utopia of merry soldiers dressed as Santas and elves. This is a very “American” principle, evidenced in many Hollywood movies that will, for example, show adults at NASA goofing off, rolling their eyes, acting like big children or cartoon characters, with a limitless supply of snark and appropriated black talk, “oops, my bad,” “oh hell no”.

Carlo Ginzburg. (DeMarco Photo).

There is another sort of semiotic register here. For in Hollywood film today this childishness is usually set against workplace activity, and then also it is an attempt at this new populism. Hollywood producers have never had to work at a discount shoe outlet, or McDonalds, or dish washers. They know as little of that world as they do of the military. But it all presented in nearly identical terms. And since the most oppressed community is arguably the urban black community, it stands to reason that this snarky goof off sarcasm should appropriate from urban black communities. Except of course it’s not really any recognizable black community, it is a TV or movie black community, just as the military is a TV military, not the real military. They talk the same everywhere, and they are infantile everywhere.

I wanted to touch again, briefly, on this question of mimesis and clues, of an idea of mimetic experience that started to atrophy with the loss of memory associated with the oral tradition, and then more acutely with the invention of printing. When I see, as an example, the work of Louise Nevelson (and I have mentioned this before) I feel my chest tighten. My breath is momentarily constricted. There is a certain cruelty in Nevelson, and I’d imagine her work touches on something masochistic in one. It is that foreclosed space, that sense in her monochrome work that we are suffocating. It is claustrophobic, too. In fact it is just generally phobic. And Nevelson is an example of an artist who instinctively, I think, gravitated toward something pre-grammatical. Here is the terrifying night sky of early nomads. It is inarticulate in that sense. Sounds are muffled. They are there, but we cannot hear them. When Panofsky noted, in 1927, that Roman painting gave us a perspectival organization or system that *consumed* the objects in those paintings, and that in Roman landscapes there is something unreal and *inconsistent, like a dream or a mirage*, he was also registering something akin to this idea Ginzburg introduced with the bird droppings and details. The clues. For the Roman artist, there was no assurance that such details, such unconscious clues, existed — but an unreality or uncanny is introduced anyway. In the early 20th century, travelers to the middle east or Africa, or just southern Italy and Greece, would buy postcards of famous ruins or sculptures, even landscapes, and paste them into novels they were reading. Self illustration. For the artist of Pompei, the detail was implied, instinctively, from a connection, historically, close enough, to nomadic search.

Kurt Schwitters

“The flowing robes of Florentine paintings in the

15th century, the linguistic innovations of Rabelais, the healing of the king’s evil

(scrofula) by French and English monarchs (to take a few of many possible examples),

have each been taken as small but significant clues to more general phenomena: the

outlook of a social class, or of a writer, or of an entire society.’02 The discipline of

psychoanalysis, as we have seen, is based on the hypothesis that apparently negligible

details can reveal deep and significant phenomena. Side by side with the decline of the

systematic approach, the aphoristic one gathers strength-whether through a

Nietszche or an Adorno.”

Carlo Ginzburg

Ginzburg mentions the Arab concept of *firasa*, which is taken from Sufi philosophy. It means the ability to leap from one small detail to somethihng larger, but unknown. A spiritual insight. Derrida, in a critique of Heidegger, criticizing the latter’s privileging of speech and poetry over the other arts (meaning space and architecture) wrote “…there is a certain Heideggerian phonologism, a noncritical privilege accorded in his works, as in the West in general, to the voice, to a determined ‘expressive substance’.”Mark Wigley points out that Derrida accuses Western metaphysics of subordinating space to the privileging of immediate speech. For Derrida there is a sublimating of space in the entire Western canon, and as this relates to artworks in the context of clues and details. For space, says Wigley (interpreting Derrida) is associated with death, decay and degeneration. Speech is life and space is death. But whether one accepts this or not, the idea of space here is relevant. For writing per se excludes space. It prohibits it. Space is outside of writing. Again, this is not to get into an argument around Derrida circa Grammatology, but rather to see the idea of space is one of expansiveness, of that search for marks, for bird droppings or paw prints. It is foundational to writing. Space is an effect of inscription, as Wigley puts it. This is, I think, clearly correct. And yet, in another sense the opposite is true. But what does this mean for a culture that no longer really writes or speaks? The screen life is one of reading image.

Alfred Eisenstaedt, photography. (La Scala, Milan, 1934).

This is linked to that impulse of control that comes out of standardization. The instrumental logic is a logic of control. And it is not space, but the containment of space. There is another idea Derrida introduced later, in a piece on Lacoue-Labarthe’s work, where the concealment of space, psychically (to be reductive) is symptomatic of repression. This is really sort of the heart of the issue and it ties together the standardized instrumental tacit rejection of intuitive space, of experienced mimetic space, and that of control and domination, of the mentality of those — here meaning an Imperialist West — who gravitate toward punishment and domination.

There is a mimetic history to spatial conditions; thresholds, entrances, borders, containers, enclosures, and per Wigley again, the more particular figures like labyrinth, column, aperture, plaits, whorls, and nautilus. And it is not *space* per se here that is denied, it is that which follows upon the search. For the clue, the mark left, an effect that is an aspect of duration, that is productive of how *space* is experienced. And that experience is conditioned and shaped by historical conditions. And naturally enough the mimetic leads at some point to the interrogation of identity. For interity is conditional in a sense, it is always ‘my’ interior. And here there are double registers of meaning because, if one were to allow Derrida into this discussion, the marks of the text are already there, and the erasing of these clues forever will fail. This exceeds the intent of this posting, but the brutality of the West, of Capitalism and coercive exploitative class conflicts, are carried out in the contemporary non-space of the security state. And this warrants a final couple thoughts on the uncanny.

That ‘which does not belong in the house’, the familiar, but too familiar, and which haunts the subject, scares the subject. Space is associated with absence, with death. The double is a portent of death, but only by returning, and returning the subject to a repressed earlier scene. Or place. Freud’s ideas of the institution of the family, shaping desire, contradictory forces that produce ambivalence. The family is the space of contradiction, as the personal history of life and death instincts — union and separateness, independence and dependence. The space of unity is disrupted in childhood, the parent/child relationship recuperates that which was split, but at a cost. The drama, the stage of this drama, is in a space. The home is the theatre of anxiety.

The question here then is to understand the shrinking psychic stage, and a near enforced regression for most adults, today. It is not too much, certainly, to see the images of soldiers and the children of occupied people playing games as a kind of representation of death, but neither is it too much to see most sit-coms as representations of death. Lena Dunham is no less morbid a figure than Dick Cheney or Hannibal Lecter. The smiling Bagram Santa in Forte’s astute analysis of military propaganda is a representation of 21st century grim reaper, but then so is Adam Sandler the composite figure representing a post modern metaphorical Torquemada. The killer of culture.

“Anti-Semitism is based on a false projection. It is the counter- part of true mimesis, and fundamentally related to the,repressed form; in fact, it is probably the morbid expression of repressed mimesis. Mimesis imitates the environment, but false projection makes the environment like itself. For mimesis the outside world is a model which the inner world must try to conform to: the alien must become familiar; but false projection confuses the inner and outer world and defines the most intimate experiences as hostile. Impulses which the subject will not admit as his own even though they are most assuredly so, are attributed to the object-the prospective victim. The actual paranoiac has no choice but to obey the laws of his sickness. But in Fascism this behavior is made political; the object of the illness is deemed true to reality; and the mad system becomes the reasonable norm in the world and deviation from it a neurosis.”

Adorno and Horkheimer

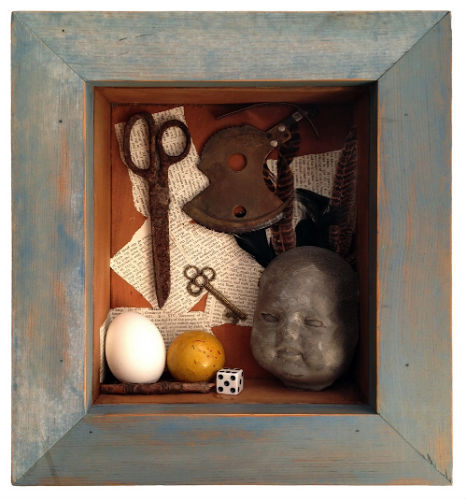

Joseph Cornell

Laura Cummings wrote of Joseph Cornell:

“Joseph Cornell (1903-72) had the mind of a visionary and the methods of an archivist. He accumulated odds and ends from the real world – a bird’s egg, a marble, a foreign stamp, a thimble – and assembled them into enigmatic dreams.”

Joseph Cornell

“But the root of Cornell’s genius as a filmmaker is his singular version of montage. Cornell’s version of continuity is the continuity of the dream. He does not juxtapose images so much as suggest unlikely — but still vaguely plausible — connections between them. Hobart’s clothing may change suddenly between shots, but her gesture is continued or she remains at a similar point in the frame. Unlike most collage filmmakers, Cornell does not rely on cheap irony or non sequitur. His films are unsettling because their inexplicable strings of images are like reflections from the deep well of the subconscious. In fact, one of the most arresting images in Rose Hobart comes when a solar or lunar eclipse is paired with the image of an object falling into a circular pool of water. Hobart simply gazes bemusedly at this spectacle, as if it were little more than a parlour trick.”

Brian L. Frye

Cornell’s brother was confined to a wheelchair for most of his life, and Cornell tended to him. Somehow, this idea of confinement is always present in Cornell’s work; sadness, anxiety, enclosure. I can only look at Cornell’s work for short amounts of time. Too long and I begin to feel that claustrophobia, and like Nevelson, there is cruelty. But with Cornell it is far less grand or expansive. That is the part one must leave, that pettiness or smallness in Cornell. He was visionary, to be sure, but also disfigured somehow. Proximity comes at a cost, as it must have in real life as well. But that sense of pinched hermetic angst is opened up in the few experimental films he made. Suddenly, the hunter of clues occurs in time. The inscription, the film, constitutes a space, because we read these films, perhaps more than any others of which I can think. Rose Hobart is accompanied by a kitschy Brazillian dance music soundtrack (Nestor Amarale, of Three Caballeros fame)and somehow this is perfectly evocative of what happens with cinema, the peculiar and particular dream sense that one slips into.

Richard Tuttle

Cornell’s films in the end are very minor. And part of that comes from the uncomfortable sexual fetishizing that drives each of them. Obsessive and slightly unwholesome, and yet this would not feel at all problematic if Cornell were a Genet or Burroughs, or Richard Foreman or even a had taken something of the erotic bravura of men he knew as friends, DeKooning for one, or simply submitted to his mania in some more fulfilling way. The potted palm soundtrack and the blue filter, the slowing down of the projection; all of it is oddly too close, perhaps, to camp. And that Orientalist kitsch quality is both intentional, and a commentary, and not. And as I watched it this time I felt well, it *is* in fact a kind of deeply strange inscription, a private language, a genuinely unconscious artifact. Cornell is a bit like many other formally untrained artists and writers of mid century; Cornell Woolrich comes to mind here, repressed, living at home, sexually ambiguous and oddly Mother fixated. It is that isolation that I think one feels most with Cornell. Nobody with a healthy social life makes thousands of little boxes with junk inside them. His work didn’t develop. It was as it is, and that is that. I don’t think anyone would want to live with a Cornell box in their house. Cornell was to be seen as a Henry Darger figure, but then also was to be seen as a Man Ray figure. The socially odd savant aspect is what cannot be avoided somehow. He ends as a profound footnote to 20th century art, but a revealing one in light of thinking about details and clues and detection.

Wow!

Wonderful essay on contemporary ideological charades n confusions.

Thanks. Have shared it on my fb wall.

Wish you a very happy new year.