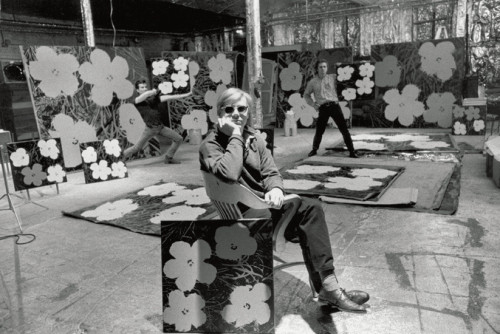

Andy Warhol (Electric Chair, 1967).

“Ah, children, be afraid of going prayerless to bed, lest the Devil be your bedfellow.”

Cotton Mather

“McCarthyism is Americanism with its sleeves rolled.”

Joe McCarthy

“Indeed, for Godard, the ethical is inherent within the aesthetic and will be revealed in the unique poetic processes of cinematic montage (“at the time of the resurrection”).”

James Williams

“The general influence of divine maintenance is not sufficient for

the preservation of the moral good of creatures: the latter also needs that of

grace.”

Matthew of Acquasparta

In the current New York Review of Books, Geoffrey O’Brien reviews Patti Smith’s new book (not to mention this piece in the Guardian : http://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/oct/15/1970s-new-york-lou-reed-patti-smith. )

I wanted to start with this because it raises a couple issues I wanted to talk about anyway. Now, I knew Patti very slightly back in the early 70s. I was in NYC most of that time, and Terry Ork would take me over to the Chelsea to visit Mapplethorpe, and I was a regular in the back room at Max’s Kansas City. I didn’t like Patti on a personal level, and I’m pretty sure she didn’t like me. I thought Mapplethorpe was an asshole, but I didn’t know him well either. But I’ve come to admire aspects of what Patti stands for. Still, when O’Brien quotes her work, like this except, about viewing London from the back of a taxi (sic): “all disappearing into the silvered atmosphere of an interminable fairy tale…flanked by the shivering outline of trees, as if hastily sketched by the posthumous hand of Arthur Rackham.” I wonder that O’Brien, a usually very good critic, doesn’t grasp just had bad that is, how pretentious and sort of faux intellectual. And this is the problem. Patti did one good-ish pop album that I remember everyone playing at that time, and even now when I hear Redondo Beach I am taken back to the lower east side of that era. But she is a terrible writer, and a simplistic thinker. But, I still sort of oddly admire her ‘iconic’ stature, what she has come, sort of, to stand for. I say sort of because I try to reconcile that cameo she did on Law & Order: Criminal Intent. Or an odd appearance on Conan, that is barely more than embarrassing. The thing that interests me is what O’Brien says about that era, the early 70s in New York. The fact that young artists of all sorts were able to come and live comfortably on no money and in cramped rooms, but still, without great anxiety, and without great fear. The world of MFA degrees and institutional imprimatur had not sucked the life from the culture yet.

I never *got* the scene in NYC, I didn’t like the band Ork managed, Television, and I couldn’t stand Tom Verlaine, nee Miller, (Patti’s boyfriend at the time and ponder that name change just for a moment) or the erstwhile writers/guitarists like Richard Hell. I hung around CBGB’s because I had a tab, and Ork was partly running it then, but I again, didn’t really get it. I remember digging Talking Heads when they auditioned, and told Ork they should book them. They would have anyway. LA certainly had its own version of scene’ster, and most were even less intellectual, and even more craven, but there was always something that creeped me out about NYC, a kind of smug and self satisfied quality of entitlement from these mostly white suburban kids. Mapplethorpe was from Long Island, Patti though, was from Jersey, by way of Philadelphia and I do recall her mom, I think, was a Jehovah’s Witness. And she, to her credit, was clearly not suburban. And that background allowed her a certain clarity I think. And I was a kid, then, hanging out at Theatre Genesis, and I was there for the one performance of Cowboy Mouth with Sam and Patti. I got to know a lot of the Warhol people, and worked for some doing odd jobs. I was, though, fond of many of the poets (Ann Waldman was a beautiful presence), and jazz musicians …Braxton and Ornette, and the other odd fringe Stockhausen clones. But I was never part of it, never comfortable either, with any of it. Already by the 70s there was a streak of destructiveness, spiritually, running through the arts scene. That destructive psychic golem ended things, really, by the early 80s and people began to leave. It wasnt destructive danger, it was a creeping subliminal conformity of destruction. There is a curious anecdotal piece by Terry Castle, from 2005, on Susan Sontag, in which she describes a party in New York at Marina Abramovic’s chic empty Soho loft, attended by Lou Reed, and Laurie Anderson (party must have been around 2002) and a gallery owner resembling Dieter Sprocket. It captures the insufferable sensibility of twee boredom that New York had descended into by then.

Warhol, at The Factory, 1970.

So, to return to O’Brien, and this essay, what strikes me the most is just how acute, now, is the colonizing of culture by academia and by the hegemony of large telecoms. Together they form a nightmarish exterminator class consigned with the mandate to wipe out art. In the 70s and even into the early 80s, but less so, there were probably ten private film clubs just below 14th Street, and who knows how many more in Brooklyn and Harlem. And I mean large well attended clubs and every night of the week you could go see a Sirk or Ulmer, a Bergman or Pasolini, a Lang or Godard, or an obscure early Nick Ray some place, or catch a triple bill on 42nd Street. Ork and I saw at least one film every single day. And there are several art houses, too. And the audience was informed. There were huge debates about Cahiers critics, Sight & Sound, or Positif. There was still a lot of theatre happening, and lots and lots of painting. I remember later, in 2003, teaching at the Polish National Film School, I was speaking with professors who reminisced about the 60s and 70s in Lodz and Warsaw, the all night arguments over the comparative value of King Vidor and Eisenstein. That same sense of culture mattering. But looking back I can see that we all felt something by the early 70s, a something that nobody wanted to talk about, but which everyone knew was there; it was a like the dark cloud of a cultural plague coming. A societally engineered blight on the culture, and it made everyone more hostile than usual. Nothing lasts and such eruptions of anti-establishment cultural anarchism are meant to die out. They have a built in expiration date. And that wasn’t the problem. It was how fucking fast the artists themselves sold off all sense of oppositional posture even before the natural decline of energy. And maybe that was what was lacking in Patti, too, a political vision — one that exceeded a sort of junior high level reformism. Her sense of integrity has always been mediated by her self promotion and self mythologizing. The political vision of the UK writers of that era, or those in Germany and Austria, and even France, is stark when compared to those in the U.S. Who in the U.S. would be comparable to Heiner Muller, or Handke, Pinter, Von Kroetz, or Fassbinder and Oberhausen Manifesto directors? Such thought experiments are pointless and sort of unreliable anyway, but still, I cannot imagine people in MFA programs investing themselves in art in quite the same way.

Vija Celmins.

The political expression in the off off Broadway of the late 60s and into the 70s began to fade, replaced with identity politics of various sorts, and more, by a generalized sense of pandering. Warhol had nothing else to say, if he ever did, really, although I think the early 60’s work was not insignificant, actually. But by the mid 70s it was just business, and accommodation to more business. Truman Capote described Warhol as “a sphinx without a secret”. I remember feeling this back in the late 70s. The society was changing, or that part of it that I was interested in. I was only in my early twenties then. Then, in 1985, Waldermer Januszczak wrote:

“In Britain we have seen the Arts Council’s transformation from a reasonably independent supporter of the arts into a government poodle worthy of Sir Edwin Landseer. We have seen the introduction of corporate sponsorship into our galleries. Private companies have been invited to set up advertising stalls in highly attractive shop-windows paid for out of public money – our museums. The most disgraceful union of art and commerce took place last summer at the Tate Gallery when the United Technologies Corporation, which builds Sikorsky helicopter gunships and helped develop the cruise missile, sponsored the George Stubbs exhibition. It was like hitching a tank to a dappled grey. What kind of moral breakdown has opened the doors of our museums to arms manufacturers? The answer is, I suppose: a complete one.”

Philip Harris

Probably no critic in a mainstream publication would write that today. It smacks too much of a kind of cultural seriousness. There was a cultural shift, a change of identity for American workers in the 70s. And a lot of this shift came out of anti communist ideology that was coupled to global shifts of industrialization. In the U.S. the south failed to unionize after WW2, mostly due to the deep racist values and persistent red baiting. By the 70s, the financialization of the economy intensified the disinheritance and marginalization of the working class that was already starting due to global factors; cheap labor in the 3rd world and reindustrialized nations recovering from the war, automation, and the fracturing of solidarity caused, no doubt intentionally, in part at least, by the ownership class. The Nixon years were schizophrenic in terms of labor’s self image, and racism really was the hidden engine behind so much of this by the 60s (not to mention the additional factor of Nixon’s opting out of the Bretton Woods agreement in 1971). With Reagan came the crushing of unions and a new Gilded Age (Jackson Cowie). It is more complicated than this, but culturally the rise of marketing pushed the idea of American individualism. The hundred years of labor resistance was ending, and part of this revanchist myth of individuality was a new historicism. It is important to note, too, the stratification within unions themselves, or between unions. Business oriented unions were oppositional to rank and file, and the steel and auto industries, too, were, by the 70s, complicit with ownership. The point here is that culture in the 70s was changing, and it marked the start of a long trend of marketed images serving to replace reality — Hollywood and PR firms were re-shaping the working class consciousness, which was there to be reshaped due to the loss of jobs, wage reductions, and a sense of psychic fallout from the Vietnam war. The start of the 70s also included the Iranian revolution that ran a U.S. puppet out of power. My memory is that almost nobody really believed in the Vietnam war, but many worked overtime to try. The pro war reactionary white man never really bought in, their cynicism didn’t stop them from hating hippies and the anti war movement (and civil rights) but they knew, deep down, it was bullshit. This may well have signaled the start of a profound loss of community in real terms, but also psychologically. And the birth of the new cynicism.

Governor Reagan with Palm Springs police chief Bob Cordes, 1968.

The white male worker who imagined himself middle class was seeing in the contradictions of the Vietnam War a kind of hologram projection of his own inner emotional contradictions. The New York I new in the early 70s, and disliked finally, was one that self isolated, largely, and in all those artists there was very little political engagement (except in theatre, and even there it was waning). The artists who protested the Vietnam war were largely poets: Bly, Ginsburg, Kinnel, and Lowell. And theatre groups, and some musicians. I don’t remember the cool kids though, from NYC, having any involvement in politics at all. There was a defacto alignment with the establishment. Warhol had tea with the Shah of Iran (former Shah) and so that sense of irony that emerged a decade or so later can be seen in all that posturing and narcissism I’ve come to associate with the key figures of the NYC cultural scene of the early 70s.

Carolyn & Peter Lynch.

It is interesting to compare Force of Evil, Abe Polansky’s 1948 New York noir with, say, Dirty Harry (1971), and then with contemporary cop shows. The representation of society has changed. From an almost Shakespearean crime version of ‘vaulting ambition’, to a vigilante proto fascist police drama, to the openly police state apologetics of Dick Wolf or Bochco. The shift in the 70s was the start of an erasure of narratives that combine society and the psyche of the individual. John Garfield’s torment, his voice over as he searches for his brother at the end of Force of Evil, is an indictment of society, but more of what it does to humans, to ourselves. Eastwood marks the elevation of a kind of white male anger. An anger caused by the broken promises of the American dream.

Rona Pondick

The cultural shift that began in the mid 70s, effectively, matured under Reagan into a technological utopianism (Steve Fraser) that media promoted as a triumph of Capitalism, a populist capitalism where anyone *could* become a jillionaire. This was what is now often called Casino Capitalism. But its effects run very deep culturally, and this enthusiasm reported by media, was in large measure illusory. But not totally. The collective sense, in white males anyway, that the Vietnam war was a loss of potency, became rebooted as the victory of the Cold War. This was the Reagan era, and what separated it from the 1950s was a far deeper trust in technology, a justification for the depersonalizing of a cyber driven market, a stock investor dream defined by electronic logic. This only intensified in the 90s, under Clinton, whose terms as President were likely far more destructive psychically than even Reagan’s. At major universities, business schools saw a spike in enrollment and MIT started a *Financial Engineering* department (an entire department!). This was also the real birth of what Randy Martin has called the risk management culture. And that logic began to pervade the lives of individuals. A risk averse culture took hold. The image of the ‘new’ culture of technological stock investment cool featured guys like Peter Lynch (Magellen Fund) and Warren Buffet, and Charlie Munger (Berkshire Hathaway). In a sense, this was the reclamation of Wasp white male power and authority. A business techno Patriarch. This was also, of course, the age of Silicon Valley. As Steve Fraser rightly points out, suddenly under Clinton, finance was the new bastion of authenticity. The Steve Jobs myth, Larry Ellison, Mark Zuckerberg, and the opaque nature of these symbols worked perfectly because most of the populace that felt buoyed by the sense of restored American virility felt no particular need to really understand any of it.

The cultural effect in the 90s was evident in Hollywood; not just in obvious Wall Street locals, or stories of venture capitalists, but in a new white supremacism, one not of red necks and confederate flags, but of liberal internet sophisticates, and the fall out of this is still seen in many lawyer shows and even, really, in a lot of police narratives. The police were protecting this new authentic realm of American exceptionalism. Protecting it from those just not smart enough to participate. The poor were a threat, and that meant mostly black and latino poor. But it was also captured in an aesthetic that pretended a disdain for materialism. There were countless, and still are countless semitoic sub groups of liberal bourgeoisie that see industrial quality home kitchen as non-materialist. The rise in luxury SUVs speaks to this as well. In a sense, this was the aestheticization and individuation of politics; a substitution of actual political issues, of Imperialism and militarism with personal lifestyle choices. Natural fabrics and whole foods (sic) became a kind of commodity politics, but also an expression of personal taste. Individualism was shopping expertise. The fall out that came after things unraveled, didn’t really alter the course of U.S. culture. For that culture is in the hands of those who do not suffer from economic downturns.

Hannah Goff, photography.

Today, one in eight residents of the U.S. are foreign born. It was Clinton who stealthily killed the last welfare protections for these people. From the 1950s on the twin and overlapping forces of anti-communism and racism set the foundations for Reagan’s war on welfare. And Clinton simply updated the idea of white potency, the Patriarch was youthful but still a white man from a confederate state, a slave owning state. Calling Clinton ‘Bubba’ is one of the soft codes that incorporates overlapping meanings — southern good ol boy, which in turn is code for working class racist. Its also linked to West African dialects, I’m told, hence its origins in the southern states, and its proximity to plantation imagry.

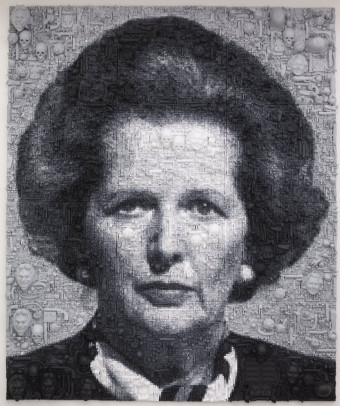

Marcus Harvey

The increasing narcissistic commodity culture also has fueled the medicalizing (and pharmaceutical-izing) of states of being, essentially. Few things have demedicalized (some though like masturbation, a word I’ve used twice in this posting, perhaps unsurprisingly given the topic) and a few things have shifted into individual rights issues connected to disability and mental illness. But mostly life is increasingly medicalized. The new religion of the restored white Patriarch is science and medicine and technology. They all go together. The effect culturally of AA programs is huge, as I’ve written about before, but it was medicalizing what was formerly a weakness of will, or moral slackness. The consumer consciousness must shop for everything; everything becomes a store. There is the illness store. And the store onwers (for medicine its AMA and big pharma) want to provide a new fall line of ‘sicknesses’ and ‘conditions’. Alcoholism is now quite popular, and menopause, and recently there was some success in turning sex addiction into a credible syndrome. Sleep disorders are popular right now, too.

Ok, but to return to cultural shifts, there seems a connection between Warhol, Reagan, Thatcher and the growth of this generalized autism that Debord described, but also of psychic blankness as a virtue, of anti intellectualism as the golden mean, and of hyper-individuation. The bobo’s that David Brooks described are in fact the Reagan dream people, who ran through the prism of the Clinton era. Reagan was visibly dumb, slow, probably already suffering the front edges of Alzheimer’s while governor. And Thatcher was remarkably similar, really.

Arthur Tress, photography.

R.W. Johnson wrote: “Mrs Thatcher is an extremely limited woman, energetic and ruthless, but seldom able politically to see very far ahead, innocent of economic knowledge, and equipped only with the right-wing suburban views common on the Tory back-benches in the Fifties when she entered Parliament.” The sphinxes without secrets, all of them. But how much were they a projection of a generalized shrinking of consciousness in the populace? That toxic cultural cloud that loomed over the mid 1970s was one in which an alien virus came and ate our consciousness. It was the virus of conformity and compliance and obedience. The fact is, class struggle, and class tensions only exist in U.S. culture if they are expressed in narratives of gender and race. The obscuring of class is almost the primary activity of mass media. This was Reagan’s fantasy, too, in whatever dimension of reality he inhabited, and the anti intellectualism of both Reagan and Thatcher was justified by their pandering to wealth (well, Thatcher married into wealth) which is the ideological dry wall put in place for every conceptual practice that occurs. That looming dark cloud was the spectre of a new feudalism. And the front edges of it were felt in Reagan, and then more acutely in Clinton. People say 9/11 changed everything, which is really sort of nonsense. Things changed with Vietnam, and the government reaction to it, just as the Iran hostage taking made the nightly news. The wagons circled in Washington, and the Wall Street shot callers began to see and believe their own ideology I think. New age Ayn Rand, and THIS set of factors came together to shape the late 80s, and then more, the 90s. Im convinced, at the end of all this that that sense of anxiety I (and others) felt in NYC in the mid or even early 70s was fulfilled in the 90s under Clinton. For Clinton and the 90s was the logical next stage after Reagan. Hillary is the nightmare dark side of Nancy Reagan. The autocratic openly sadistic merger of Thatcher, Nancy and Madame Defarge. Contemporary life is lived in the psychic rubble left after the nuking of consciousness under Bill Clinton, and now, soon, in the hands of the first genuinely insane person to be President. Trump would be a blessing compared to Hillary. This is life as metaphor, as allegory. Leaders are often blank canvases on which are projected various deflected wishes or fears. Nixon had a certain Shakespearean tragic/comic grandiosity, and his ugliness and awkwardness was also a bit Richard 3rd like — but Reagan and Thatcher is the apotheosis of grandeur. Their message, their image, was always partly that such things don’t matter. When Reagan, as governor, said something to the effect of ‘if you’ve seen one Redwood, you’ve seen them all’, and then signed away a chunk of remaining protected national park, he was eliminating lives of richness, eliminating metaphor, allegory, fable and myth. Just get me a good tee time at Indian Wells. He was spraying cheap plastering over the original medieval tiles of consciousness. He was making it alright to be ill educated and slow witted. As long as you were square jawed, white, and believed in the market.

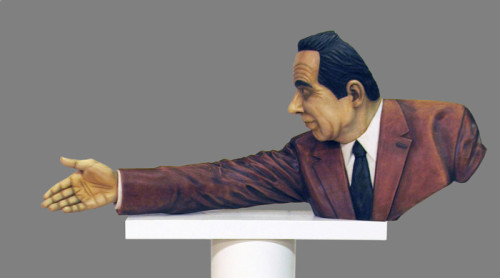

Bob Trotman

But culturally now, there is a sense of retreat in fine arts. A confusion of premise for even starting to pick up a brush. In film, there are signs of an oppositional vision forming. But in prose, I find almost nothing for I think the MFAization of the novel has killed it, finally. Its been sick a long time. The decline of fiction can be marked, in a limited perspective, from Gaddis novel JR, and follow that through to Franzen’s The Corrections.

The MFA model was parodied brilliantly by one Frank Jackson in a letter to the London Review of Books, December 2012.

“…why the first sentences of so many stories in the Best American series follow the same formula. Start with the words ‘when’ or ‘after’; mention the first name of a character; dangle a pronoun with no antecedent; drop one heavy symbol or allusion; and use vaguely abstract phrasing to lay out a fairly banal situation. Here’s the first sentence of Maile Meloy’s story ‘Demeter’, about splitting child custody, in the 19 November issue of the New Yorker: ‘When they divided up the year, Demeter chose, for her own, the months when the days start getting longer.’ “

And speaking of Franzen, there is this (which a friend sent me)……………http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/2/6a563a5a-6cde-11e5-8171-ba1968cf791a.html

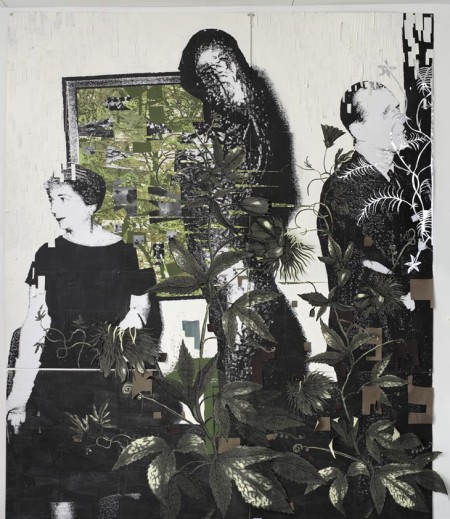

Kirstine Roepstorff

The art movements that coincided with Warhol, outside the U.S. such as Fluxus, Nouveau Réalisme, Gutai, and Arte Povera, seem now, mostly, a lot more interesting than Warhol does. This was the sixties though, and again, the rebelliousness of the New York scene in the 70s certainly had some inhereited virtues, and in theatre, the off off movement was probably more important and influential than anyone realized. The Padua Festival in southern California was directly linked to off off with Shepard, Mednick, Irene Fornes and Walter Hadler..and even the San Francisco artists, John O Keefe and Martin Epstein, shared a sensibility with off off. But I think its very useful to look at this period from the mid 70s through 2000 — for it represents a changing of consciousness in the West, overall, and acutely in the U.S. The rock n’roll sensibility of Patti Smith, Jim Carroll, and the Ramones was pretty shallow stuff, and felt, even at the time, like something that was drawing energy from elsewhere rather than from *there*. If you examine the mass commodification and the saturation of social media today what one sees beneath the surface is a psychology of containment. This is linked to this medicalizing model of health, which shares notions of control with architecture and narrative and marketing. As Furedi noted, the public has internalized medical and therapeutic perspectives as a basis for subjectivity. In the 80s, Peter Conrad notes that the medical profession shifted (per Reagan) from concerns of access to cost control. And this gave birth (sic) to the idea of managed care. And managed care is a very insidious idea. For one thing it positions the patient as a consumer — a buyer in the great mall of medicine.

“Some of these changes have already been manifested in medicine, perhaps most

clearly in psychiatry, where advances in knowledge have shifted the focus in three

decades from psychotherapy and family interaction to psychopharmacology, neuroscience,

and genomics. This shift is reinforced when third-party payers will pay for

drug treatments but severely limit individual and group therapies.”

Peter Conrad

Nancy Reagan, Harriet Deutsch, Leonore Annenberg and Jean French Smith. Palm Desert

Generally 1985 is the watershed year for the establishment of biomedicine as the platform of dominance. When medical concerns become consumer concerns, there is a market reaction; i.e. those big corporate holders of patents will push certain models of health, and more of illness in order to maximize profit. The growth in the early 2000s (well, end of the 90s) of SSRI usage and prescription is the logical result of the shift in medical models that occurred in the 80s. So am I suggesting a link between the waning artistic avant gardes, or pseudo avant gardes, from the 60s through to maybe the very early 70s, and the shifts in the idea of health? Yes, and also with the Clinton era shift toward risk averse thinking, and restoring of White patriarchal virility and potency. For an aspect of Warhol’s influence was in the erasing of depth, but more specifically with the loss of a Dionysian energy. And in that sense the brief 70s punk scene was brief flickering final eruption of sexual energy, even if already compromised. It was Dionysus as cadaver. The necrophillic eroticism of Lou Reed and others suggested enough self awareness to know this Bacchanal was taking place in a morgue.

Diathermic treatment of asylum inmate. 1920s. Location unknown.

The Wall Street capitalist patriarch, often referred to as ‘the big swinging dicks’ is part of the fall out from the hollow image of cold war victory– the Peter Lynch or Gordon Gecko alpha male image was linked to a transformation of idea of masculinity. Again, in medicine, the shift was toward manliness rather than an ability to reproduce. Hence new products for male pattern baldness, andropause (male menopause) and erectile dysfunction. That the young wall street investors and speculators of the 90s were heavy users of high end call girl services should not be surprising. The patriarch and his clan, the white men of techno cyber heroism and authenticity were in a weird way the legatees of Warhol as much as Reagan. Perhaps the only living metaphor was ‘big swinging dick’.

Paul Street, writing of the post WW2 period in the U.S. notes, among other things:

“*The birth of a bourgeois identity politics that has provided populace-dividing service to the corporate and financial elite across the subsequent neoliberal era.

*The criminal and mass-murderous U.S. imperial wars on Korea, Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia, which killed more than 6 million Asians between 1950 and 1975.

*The marginalization or radicals and their ideas.”

Street also notes the union capitulation to ownership, and the massive expansion of the Pentagon. The Clinton years saw the consildating of a number of forces that took shape under Nixon. In some ways Clinton resembles Nixon more than Reagan. But the point is here that culturally the effete institutional aesthetic of conformity and de-politicization of art, in all mediums, rendered not just artists but most critics, too, as voices of validation for the status quo. The public, ever more atomized, began to embrace fantasy over reality.

Antony Micallef

Faux criticism, and now faux news. No matter if its accurate as long as it’s attractive and hip. Or, *entertaining*. The idea of entertainment is a very crucial part of the modern psyche in the West today. It is worth seeing this, too, in light of this medicalizing of human existence.

The treatment of appearance, cosmetic surgeries and treatments for what are really just symptoms of aging began with women, and the stigma of age, but now include men to a surprising degree. But this is not too surprising. More relevant is the diagnostic system in place for mental illness. Again, the 1970s marked the beginning of certain conditions as warranting treatment; and hyperactivity was the most prominent. It was estimated at the time that something like five hundred thousand children were hyperactive. Today the estimate is seven million. But more, this turn that began in the 70s included adult ADHD. But per my belief that the 1990s marked the greatest cultural shift in modern times, adult ADHD (only so called since the mid 80s) became a huge topic.

“In 1990, Dr. Alan Zametkin of the National Institute of Mental Health and several of his colleagues published an often-cited article in the New England Journal of Medicine. Using positron-emission tomography (PET) scanning to measure brain metabolism, Zametkin demonstrated different levels of brain activity in individuals with ADHD compared with those without the disorder; these findings provided new evidence for a biologic basis for ADHD.”

Peter Conrad

Tony Roy Jones, photography. Near Morecambe, 1967.

The trend to biologize definitions really spiked in the 90s. It was also the decade in which news media began to feature stories about such conditions. This is what is really telling here, that the promulgating of this perspective, of both conditions such as ADHD, and their treatment, but also the personal stories of those suffering with these conditions became part of entertainment. The consumer of illness was choosing items frequently treated with pharmaceuticals. People who did well at work, could still be diagnosed as ADHD if they had poor interpersonal relationships. And defining that relied often on the testimony of the sufferer him or herself. The shopping for medical conditions ran alongside shopping for industrial quality stoves and luxury SUVs and specialty winter tires for said SUV. Those who receive treatment for conditions such as ADHD are self diagnosing and then going to a *health care professional* for verification (and drugs). One could script one’s own story in a sense. Today even aging is medicalized and treated as somehow abnormal.

“Since 1979, for example, some of the new disorders and categories that have been

added include panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder,

social phobia, borderline personality disorder, gender identity disorder, tobacco

dependence disorder, eating disorders, conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder,

identity disorder, acute stress disorder, sleep disorders, nightmare disorder, rumination

disorder, inhibited sexual desire disorders, premature ejaculation disorder, male erectile

disorder and female sexual arousal disorder. If you don’t see yourself on that list,

don’t fret, more are in the works for the next edition of the DSM.”

Stuart Kirk

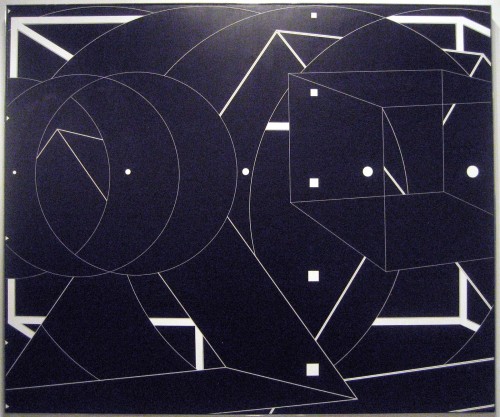

Al Held

The 90s was the culmination of thirty years in which, gradually, the idea of individuality was internalized along very strict guidelines. And these guidelines were part of a wide pattern that depoliticized life. Rarely do diagnostics include the dehumanizing repetitiveness of low wage labor, or the sheer irrationality of authoritarian schooling. Why wouldn’t one ‘call out in class’ (a classic symptom of ADHD in children). I would, and I think I did, except at those times I was close to mute and withdrawn. The medicalizing of society is also simply a continuation of ideological positions related to all science. Diane Lewis, back in 1973, made cogent observations about the nature of anthropology and its relationship to colonialism. (courtesy of Max Forte at Zero Anthropology).

“Since anthropology emerged along with the expansion of Europe and the colonization of the non-Western world, anthropologists found themselves participants in the colonial system which organized relationships between Westerners and non-Westerners. It is, perhaps, more than a coincidence that a methodological stance, that of the outsider, and a methodological approach, “objectivity,” developed which in retrospect seem to have been influenced by, and in turn to have supported, the colonial system.”

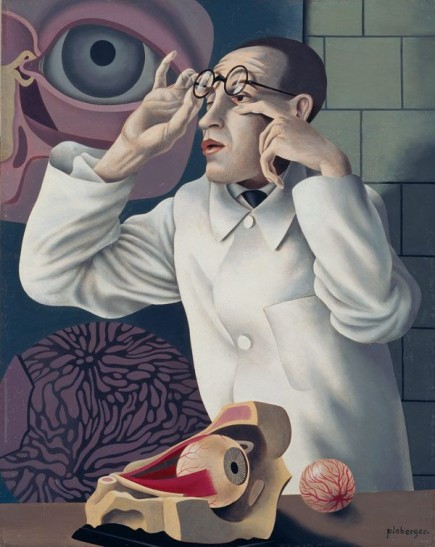

Herbert Ploberger

Benjamin and Kracauer both, in the 1920s, made observations that are related to this idea of outsider, an outsider as ‘expert’. For Kracauer in particular was critical of ‘outside’ observation, the sense of hierarchical power that resides in the viewer who is freed from responsibilities of interaction, who is tasked with taking notes and returning his information to the metropole. To the institution. The colonial logic of anthropology is linked to a general authoritarian structure involved in all science, and with ideas of extraction of information, or more, of material and people. But also with this idea of the bourgeois expert. Scientific data was to be compiled and later made actionable. In this sense, among art forms, film retains the most residue of this master/slave dynamic, the detached observer dissecting specimens. The film director in early silent films (as I think Kracauer noted) resembled nothing so much as a foreman on a chain gang. Standing aloof and observing, directing and issuing orders.

Now, this was obviously also dialectical, and cinema contained its own opposite. The restoration of memory inhabits the filmic image, and Benjamin certainly saw this, but as others have since pointed out, cinema opens itself up for extraction. The screenshot, or still, from the movie, which is interrupted, or stopped, and this image is contemplated as part of a cultural autopsy. How much art history is actually activated by cinema is an open question, but what seems more important is the nature of the effects of such massive exposure to moving recorded images in contemporary life. The evolution of this idea of *expert* arrives at robotics, really. Today the expert is not really a technician, certainly not a draughtsman, but more a scientist of sorts. And perhaps that this foreshadows an art world in which the expert is restored to prominance. The artist as scientist or factory owner, or chain-gang boss, or tier bull. I’m not sure.

Betye Saar

In 2003 Hal Foster wrote, in a review of a book by Nicolas Bourriaud…

“That we are now in such a new era is an ideological assumption, but even so, it’s true that in a world of shareware, information can appear as the ultimate readymade, as data to be reprocessed and sent on, and some of these artists work, as Bourriaud says, ‘to inventory and select, to use and download’, to revise not only found images and texts but also given forms of exhibition and distribution.”

And then quotes Douglas Gordon; “I make art so that I can go to the bar and talk about it.” It is logical that giant installations now dominate the art world, in large part because they allow for mega-marketing strategies, and the ‘spectacle factor’, but also because the recycling of an endless same, of familiar images and narratives and objects is expected, anticipated, and is hence *entertaining*. The aesthetic element, as J.G. Ballard says in an interview with Hans Orbst, has been reduced to zero. Well, that’s the idea. There is no aesthetic in non-spaces, and the forces that drove society to manufacture vacuity is traceable, I think, and it is certainly traceable back fifty years. The new art-scientist is more efficiency expert, or bureaucrat than actual scientist.

Rafal Milach, photography.

This imprint of entertainment is that which blinds the audience to image, and here I’m really talking mostly about film again, in this sense, but painting, too. The idea that Benjamin had about the messianic, and image is connected to a redemptive or liberating quality in the mimetic. Debord said all creating is resistance. Agamben links cinema with liturgical ceremonies, and fascist spectacles of patriarchal power, and this in turn is linked to gesture, to an interrupted gesture, which serves to remove something human from mass culture. Kafka even said, images in films are too enjoyable (I paraphrase slightly) and that this surplus beauty causes much anguish. One of Agamben’s best observations is that Kafka’s writing was the anti-cinema. Benjamin in a way, I think, believed this, too. But he does not mean cinema, he means mass culture, advertising and corporate media. The quote at the top by Matthew of Acquasparta, is in Agamben, and it struck and sort of haunted me all week. That ‘grace’ is art, when it *is* art, it is that image which is beautiful but brings anguish. It is the resurrection in each moment on stage in which an actor forgets.

The restoration of white male potency that began with Reagan (following the trauma of Nixon’s presidency) reached full effect under Clinton. The metaphoric ‘big swinging dicks’ of Wall Street were also the sexually terrified little shrunken dicks of an ever more anxious and threatened psyche, lords of their ever tinier domain of white privilege. Power may have and continue to be materially operative, but the metaphoric domain is ever smaller. These are people who live in non-space (as corporate Capital has effectively removed the staging areas of the psyche). The Oedipul narrative is always interrupted now, the gesture is always frozen, the gaze is clouded, or just blind, and from that terror comes great cruelty.

like Warhol (who stole from masters like Emil Nolde), Mapplethorpe was an art thief (epigone). he stole from Peter Hujar, Andre Kertesz (who told me that he hated M’s work), and Jacques-André Boiffard. Mapplethorpe was a drug addict so it’s difficult to label him an asshole. he was politically brilliant, given his intellectual limitations

Not sure where to post this link, so I’ll post it here. Interview w/ Habermas where he discusses Marx, Adorno, Foucault, Derrida, and related topics: http://www.eurozine.com/articles/2015-10-16-habermas-en.html