Thomas Ruff, photography.

“Earlier research found that dementia morbidity was occurring earlier and had disproportionately increased in some Western countries in people aged 45–74 years, with relatively larger increases in women as women’s TND rates had risen relatively more than male rates in every country. As Western women’s lifestyles have changed more than men’s this suggests possible interactive environmental contributions. This view is supported by studies of neurological mortality that found population density was a surrogate marker for environmental exposure and a similar link has been found in relation to incidence of cancer, with substantial increases in two specific neurological conditions, MND, and “early-onset dementias.”

Colin Pritchard, Emily Rosenorn-Lanng

Surgical Neurology International (July 2015)

“Naturalism assumes that the world out there is as it is, and I know that not to be the case – and most people know it. If they really examine themselves they know that their own feelings, their aspirations, moods, memories, regrets and hopes, are so tangled up with the alleged reality of the out-there, that the out-there is actually interpenetrated by feelings. Naturalism can easily lead to the assumption that you are created by the out-there and by all the imperatives of the world. Non-naturalism and its use of the inside of your head is more likely to remind you about the shreds of your own sovereignty.”

Dennis Potter, (1992)

“…in the register of the ‘I’ there exists a threshold below which the ‘I’ finds it impossible to acquire, in the register of meaning, that degree of autonomy that is indispensable if he is to appropriate an activity of thinking that allows between subjects a relationship based on linguistic heritage and knowledge of meaning, in which one recognizes that one has equal rights, without which will always be imposed the will and the words of a third party, subject or institution..”

Piera Aulagnier

“The unconscious formed between infant and mother and later toddler and mother, occurs, in Freudian theory, before the repressed unconscious. It is the era of the construction of the self’s psychic architecture. Maternal communication—a

processional logic—informs the infant’s world view. What is known cannot be thought, yet constitutes the foundational

knowledge of one’s self: the “unthought known.”

Christopher Bollas

Desiree Doloron, photography.

The second season of True Detective concluded last week. The mainstream critics hated it, and internet chatter on social media was equally negative. Still, there was a LOT of discussion, which suggests the show managed to capture a certain audience that is uncomfortable with it’s own state of mind. Nic Pizzolatto seems himself unsure exactly how ambitious he want’s to be. But its not really all his fault when HBO is the creator of formats. It is worth considering the hostility to True Detective in light of the unadorned worship now of stuff such as The Sopranos and in another way, things such as Homeland. And then, lets triangulate with the films of Wes Anderson, Spike Jonez and Richard Linklatter. What struck me about the dismissive tone of critics, was that a generalizing critique was all that they could come up with. And the demand for perfection. The Big Sleep, based on Chandler’s novel, actually has a plot that doesn’t add up. But few people care because one is wandering in a half light dream world, in which the sense of unknowing is a part of the actual content of the narrative. A specific unknowing. But one that reminds me of Bollas’ well known quote above about the *unthought known*.

Without an avant garde, per se, the role of corporate manufactured TV and film is one in which many previous oppositions have been subsumed. But not all. There is, however you approach it, something far reaching in the response to season two of True Detective. Even people who like it, who will go so far as to say, oh its not bad, but its really a mash-up of this or that and him and her. There is an absolute inability to recognize that perhaps there is something, even if partial, a fleeting glimpse of something in this season that has haunted viewers. Haunted both those who dismiss, who hate it, and those who grudgingly grant it some credit, and those like myself who think it’s, finally, really very very good.

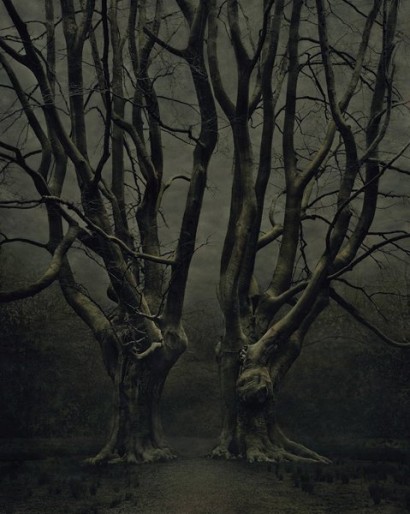

Tadeusz Wanski, photography.

Still, it is not exactly unpopular either. I mean Nic Pizzolatto isn’t going to have to hock his Porsche and Patek Philippe or max out his Gold VISA card to make his next film. In fact, how he managed to get the first True Detective on the air remains a bit of a mystery. So the real question is why the majority of, for lack of a better word, mainstream critics seem so hostile to season two, and in fact, to season one, too. For the critical response to season one was pretty negative as well. The point I am trying to get at is that today the cultural establishment presents itself, brands itself, in ways that try to obscure the fact that they are establishment. This is that faux populism that seems to have infected western culture over the last fifteen years. I will return to this below. But also, someone I know suggested that they really liked this show, but after all, it wasn’t Dostoyevsky. And it’s true, I think. But what does *that* mean?

Kristeva was fascinated with Dostoyevsky in terms of her theory of abjection. And I feel that abjection is perhaps a great place to examine the strangeness of contemporary U.S. audiences (mostly U.S. but not exclusively) in their reaction to art. She quotes Dostoyevsky’s character in The Possessed: “I really don’t know if its possible to watch a fire without some enjoyment.” Bachelard wrote: “When we first learn about fire, it is that we must not touch it.”

Alina Szapocznikow

Botticelli (Detail) Mars and Venus. 1483.

On a superficial level, I wanted to note that another factor is at work in popular cultural criticism; and that is the manufacturing of persona (often, in fact, real) that are immune to critical attacks. Lena Dunham for example. Nothing one can say about her or her trivial writing or narcissism and privilege has any traction. And this is true of many comedians and celebrities; the ironic is infused with a pre-emptive self mocking that serves to immunize this persona. These performers all *begin* with self mockery, but always of a mild variety. I am so spoiled, such a JAP, such a princess, such a spoiled frat boy, etc etc. Dunham goes further by laying out personal histories in imtimate detail, for that is part of this *act*; the confessional as initiation into critical impregnability. Additionally, with the likes of Dunham, there is in fact the revulsion factor. And it occurs to me that contemporary comedy is, in general, rife with revulsion. Saturated with it, in fact. And it is a pride of revulsion. Pryor was admitting guilt. His admissions were indictments of a system that created pathology. Dunham’s admissions are validations of the naturalness of privilege.

Carolyn Drake, photography. (‘Two Rivers’ central Asia 2007).

Abjection though, and revulsion are connected to very deep levels of psychic formation. And this is what I wanted to really examine in light of this new faux criticism that has become an internet group think, and one that corroborates a flight from anything inching too close to sublimity and revulsion. For this is also the problem with Terrence Malick, as a good example. It is a watered down sublimity, with abjection expunged and hence, a very diluted form of transcendence. And hence, embraced critically.

Kristeva wrote…“Dostoyevsky has X-rayed sexual, moral, and religious abjection, displaying it as collapse of paternal laws.” This is a fascinating idea, even if I don’t entirely accept it. She adds “Is not *The Possessed* a world of fathers, who are either repudiated, bogus, or dead, where matriarchs lusting for power hold sway…”. Well, it is one of the things that occurs in The Possessed, for like The Idiot, this is a book of presentments of death, of both individual death and societal suicide. The gambler is always the degenerate gambler, the addiction that craves abjection.

“If I had to choose a single characteristic to define man’s fatum I would choose the effect of anticipation, by which I mean that his destiny is to confront it with an experience, a discourse, a reality that usually anticipate his possibilities of response and always anticipate what he may know and foresee of the reasons, the meaning, the consequences of the experiences with which he is continually

confronted.”

Piera Aulagnier

Boris Mikhailov, photography.

Cultural criticism today exists in a strange territory between entertainment, and that of academic post modernism. The film critic is usually either writing for Variety, or the like (the prestige version of Variety is The New Yorker or Atlantic) or is part of a film studies program somewhere. The problem with MFA programs, for any of the arts, is that they tend to pretend more distance from economic considerations of valuation than they actually have. The second problem is that there is simply too much writing of all sorts. Especially on the arts. The end result is badly paid and often disinterested interns, overworked and on deadlines, who resort to the easiest positions on any particular topic. The era of alternative presses are long gone. I am going into this because it has direct influence on the audiences for artworks. Whether film, TV or fine arts, the audience senses an experience of dilution and absence of urgency. Does art feel as if it matters? At all? But then, should it feel as it matters? Those are really bogus questions, and what is maybe more germane is how much does any particular work reach into our psychic pasts and societal insanity, and express that desire that advanced capital is in the process of killing. Does this work represent revolution of any kind? Does it bring forth nausea and dreams and stimulate any kind of awakening? It doesn’t matter in the least if you *like* it. Or if it has an acceptable leftist *message*. That is simply not what art does.

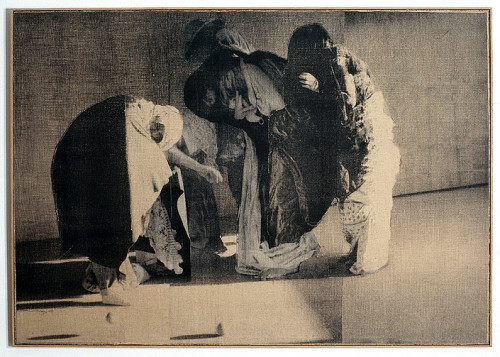

David Noonan

The current issue of The Atlantic, as a point of reference, has a *preview* of upcoming fall TV shows. It is worth reading because everything about it, from the frothy tone, to the unquestioned fawning over Hollywood in general, to the also reflexive aside on Putin, is quintessential in its sheer vacuity, but more, in that sense of mental numbness that it elicits. There is a sense that mass media is, today, almost entirely about the erasure of inner life.

“..the phobia of horses becomes a hieroglyph that condenses all fears, from unnamable to namable.”

Julia Kristeva

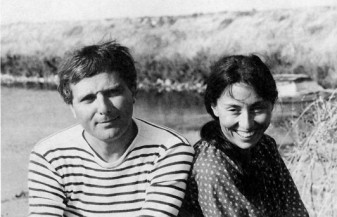

Phillippe Sollers and Julia Kristeva, 1980 (Photo: Anne de Brunhoff)

“The order governing the statements of the mother’s voice has nothing random about it and is merely evidence of the subjection of the I who speaks to three preconditions: the kinship system, the linguistic structure, the effects imposed upon discourse by the affects at work on ‘the other stage’ (l’autre scene). This trinomial is the cause of the first radical and necessary act of violence that the infant’s psyche undergoes at the time of its encounter with the mother’s voice. This violence is the consequence and living testimony, on the living being, of the specific character of that encounter: the difference between the structures according to which the two spaces organise their representation of the world. The phenomenon of violence, as I understand it here, refers in the first instance to the difference separating one psychical space, that of the mother, in which the action of repression has already taken place, and the psychical organisation proper to the infant.”

Piera Auglanier

Peter Peri

The artist is always, I believe, imparting a discourse of some sort. It is done without expectation of understanding in the conventional sense, and that means that the relationship enters into one of magic. What Auglanier and Kristeva both, and Lacan, directly believe, is that language came out of that loss of maternal contact, of tactile satisfactions; the pictographic violence or angst, the despair that forges a primal speech, and a visualized space. The central role of skulls in ancient magic are the face of the lost mother. The eating of paternal authority was likely preceded by a cannibalizing of the Mother — and here expectation and anticipation are qualities that shape the first practice of picture making. This also suggests the primal-ness of melancholy in psychic organization. Loss of mother and rivalry with the father. The infant’s symbolic adventure begins with action, with a striking out into the void, into the place where there is now,, for the infant, nothing.

“Fire illuminates itself as well as other objects. In the same way the means of knowledge establish themselves as well as other objects.”

Nagarjuna

In the Orphic version of the murder of Dionysus, the Titans surround the god-child, they are covered in white clay and wear white masks. Once Dionysus sees his reflection in a metal toy, a sort of mirror, the Titans strike and kill him, then dismember him and then cook him…before they eat him. Marcel Detienne sees in this ritualized reading of Orphic myth the beginning of early Christian religious ceremony. In all rituals there is the reenactment of primal loss, and in every creation of image and story there is a search for what set in motion this desire for completion. It is not a completion, really, that we search for, but a belief that was once there was completion. A memory that exists only in a memory we have lost access to, and could not decipher anyway even if found. But that is the point; the finding becomes less important than the journey. For the journey is always one of detour anyway. And that first staging of loss is why in every play, when the curtain is raised (figuratively) there remains a *feeling* that something or someone has just left the stage. And we are compelled to both reenact the original missed appointment, and to devise new strategies to recover a language that is extinct.

Josef Schulz, photography.

Kristeva sees in those cave paintings as Lascaux, the impossible-as-death, and the only defense is in representation. And more representation. And more. Over and over. There is additionally a question of that which cannot be named in all artworks. The infant must account for loss. But the infant is creating a language, a picture of a language in a sense. One of the things that contemporary Capitalism is determined to do, by its logic, is stop the story. And to stop the story the focus must be on that which CAN be told, not on that which it is impossible to tell.

The quality of impossibility is, perhaps, most obvious in theatre. But it is clear enough in all narratives. Today, the reflexive panic that occurs when a ‘plot’ is too hard to follow suggests that those plays or films whose difficulty is not that of mystification (David Lynch for example) but of careful remembering, stories of struggling to remember somehow, are the ones that will be fled from. The struggle to remember is, I think, linked to the reality of our own transgressions. The guilt of not remembering, and of what we *might* have done. The primal crime, then, is not just patricide or matricide, but is the breaking of an implicit taboo on re-creating our completion.

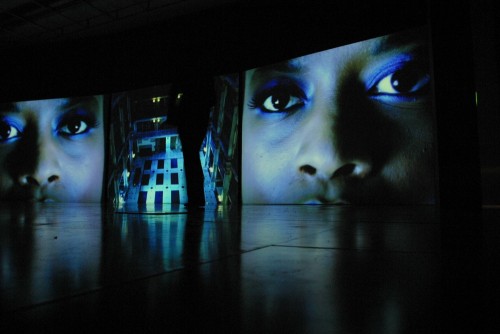

Isaac Julien. Installation.

Freud saw the archaic narcissistic self projecting outward that which was found unpleasant. Auglanier starts with the first suckling of the breast. The mouth on the breast and that any break in this state of equilibrium was to place the infant in an unknown space. A space of pain, and of anxiety I believe. For Auglanier the response was hallucinatory. A denial of this new unknown space. This is a primary mis-reading of lack. And, if one believes Auglanier, a denial that is incorporated as the failure of the pictogram. Freud posited that the primary projection was creation of an alien double. For Freud this double was a defense that substituted a benevolent other for this new hostile other, which was only known by its effect — a lack. This sets in motion the compulsion to repeat. And here, I think, is an important aspect of artworks. The repetition is modified over time. Discipline and practice become constructive compensations, ones that are geared to mediate the compuslive aspect of this hallucinatory substitute.

One of the originary figures in all narrative is that of the *stranger*. The stranger appears, enters the stage and upsets equilibrium. Except that that equilibrium is a fantasy. Children enjoy the same story told to them over and over. They never tire of it. For only adults feel this need for novelty. A need which is learned in the marketplace of culture. Older pre-modern societies ritualized familiar narratives, but rarely felt the need to find *new* stories. Today, one of the most common complaints about film and TV is that something is a cliche. There is a double edged aspect to the familiar. There is the familiar that is known, and the familiar which is a familiarity with the unknown. Kitsch is, in a sense, the repetition of the known.

“…the marketisation of the workforce, families without fathers, communities without fathers, fathers without fathers, have all contributed to a generalized collapse, which in psychoanalytic terms, is the loss of the space of this mythical Oedipal period, which as we have emphasized, necessarily inscribes in us a prophylactic loss, guilt and a sense of indebtedness to the world. No one is indebted anymore.”

Rob Weatherill

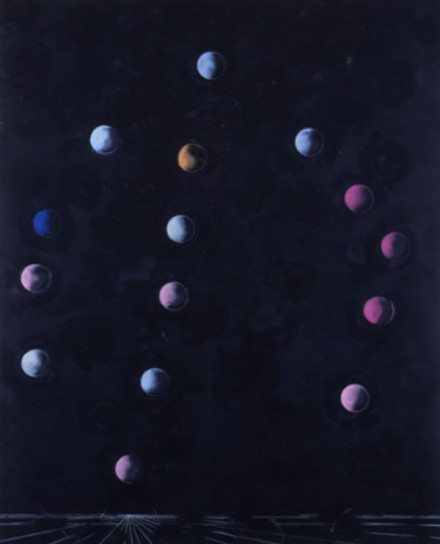

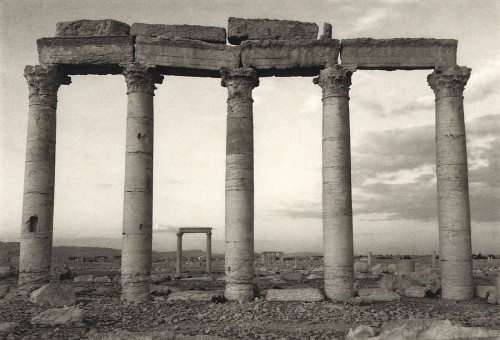

Kenro Izu, photography.

I suspect, though, per Weatherill, that today there are new forms of recuperation occurring that are creating that missing indebtedness. The visibility of these forms however is limited because the media, so pervasive, is controlled by the very most un-indebted people on the planet. That primal projection of which Freud spoke expands on a societal level. In traditional societies natural disasters recreate that primal lack, the sudden disappearance of pleasure. And hence are unbearable. The explanation then, is a ritualized reading of the event, and an attributing of this fate as punishment by God for broken laws or taboos. As Yannis Stavrakakis notes, the suffering now has a fantasmatic meaning and a cause and can be fitted into a mythic system. It is “integrated into a story or a paradigm.” Modernity and its reliance on science inscribe disasters of Nature with an acute anxiety, despite the certainty of the explanation. But it is a certainty of calculation, and hence lacks the narrative and creative on an individual level. The ascension of a scientific idea of reality, a science of Being in a sense, really returns mankind to a state of myth. Lacan wrote..“That is the dream, the dream behind every conception of knowledge. But it is also what must be considered mythical. There is no such thing as a prediscursive reality. Every reality is founded and defined by a discourse.”

This is, on the political level, the deep attraction of socialism. For the primary appeal of communal and communistic organizing of societies is that those primary experiences of anxiety, rivalry, violence, lack; all of them are granted space. The space of personal mythos. I think often this fact is missed by contemporary leftists. Stavrakakis observed that …“It is in this sense that psychoanalysis can be described as a science of the impossible, a science that does not repress the impossible real.”

True Detective 2: Western Book of the Dead. (HBO) 2015.

The purpose of art is in its purposelessness, said Adorno. And from this purposelessness comes it’s gift to people. The space to create. For creating, the acts of the imagination, are not random. Day dreaming and idleness are not valueless. It is the coercive quality of Capitalism, especially in its contemporary predatory form, that erases space. Stigmatizes personal space in the name of individuality — an individuality without an individual.

Lacan said certainty was the defining characteristic of psychosis. The study I quoted at the very top of this posting is revealing of two things, I think. One is that modern life, especially in Western urban centers, is, on a biological level, making people crazy. And two, that the onset of early dementia is not JUST a result of environmental factors. I think, without any exaggeration, that this is the result of the cultural decay of advanced Capitalism. That indebtedness is also to a world of imagination, dreaming, and story. Without the narratives of impossibility, the pathological aspect of primary hallucinatory substitution becomes dominant. So, in a sense, the importance of even corporate produced series, such as True Detective 2, is in the fact that such a show was a shadow play, the fatalistic moral twilight in which the quest for truth is allocated space, metaphoric grottoes, caves, where unnameable things are the only real language.

Dostoyevsky. apprx. 1863.

The idea of space, as it’s being used here, is both metaphoric space, and a form of mythic narrative space. The scene of the crime, the staging area of primal crime. The killing floor. Pizzolatto wrote on the U.S. version of The Killing (AMC), which was a pretty remarkable series in itself, and has cited Dennis Potter’s work as influential — and this is not surprising, really, for probably The Singing Detective (with maybe the original Jimmy McGovern Cracker) is as good as television has ever been. I suspect season two of True Detective will be remembered far more than the first season. Pizzolatto has taste. That alone disqualifies him for many. But this is not a review. I don’t know what a review is at this point. I want to know why what seems so extraordinarily obvious to me, that this is serious work, inspired in places, is being beaten like a rented mule in the mainstream media. That it is a favorite and easy target is clear — so, how and why did that happen?

“I am a sick man. I am a spiteful man. I am an unattractive man.” So begins Notes from Underground.

Benjamin wrote that the caesura “along with harmony, every expression simultaneously comes to a standstill, in order to give free reign to a power that is expressionless power inside (in the realm of) all artistic means.” This is in a commentary on poetry, on Holderin, and it relates to Benjamin’s thoughts on tragedy. The violence of the Gods, as Holderin put it, is disclosed in Greek tragic drama. Sigrid Weigel notes that Benjamin saw in Kafka a theological secret that was carried outwardly by characters who appear plain and ordinary. There is a through line from pre history and rites of sacrifice, to Orphic utterance, to Greek Tragic drama, to Dostoyevsky and Kafka. It is that the desire to write things down, to mark walls, to paint and decorate and carve, is all and always ambivalent and always a part of a quest to recover that which was lost. None of us knows what was lost, and hence the suspicion that this is personal. For why else do any of it?

Callum Morton

It isn’t that Freud and psychoanalysis have a certain appeal or even affinity with writers and poets, and perhaps more playwrights and even filmmakers; that the model Freud came up with happened to be one of a theatrical stage as a random choice. That his clinical work was based on a model borrowed from drama or literature was somehow accidental. Freud and psychoanalysis are necessary in their exact form, for that is what we are. People in the form in which we evolved, is one in which scenes occur, one after another. And we are both the author of these scenes and not quite the author, and often we don’t know which. But the scene is on stage. The idea of the stage obviously did not begin with Freud. It is there in Vedic thought, and in Orphic declarations, and the entire architecture of sacrifice always happens through a *staging*.

Art is itself on this level a kind of ur-therapy. Except it’s not therapy, as it is understood today. The story is the protection provided by representation, the sanctuary of it, and the repetitions are the practice needed as skill is needed, AND the repetitions are compulsions, mental spasms of little passing hermeneutical significance. It is always both. Always. Whatever it is, it is also something else. This is the hidden lesson of the artwork, I think.

Now, Freud and this idea of scenes and a stage are both modern, shaped by a bourgeoisie in middle Europe at the end of the 19th century. I suspect though, that the this staging of events, the forming of the psyche, of infantile trauma, is also the primordial shape of the human. That language interceded and created an additional layer of anguish. Jean Starobinski’s often quoted comment on Sophocles…

“Oedipus has no unconscious because he is our unconscious…one of the principle roles assumed by desire. He does not need any depth of his own because he is our depth…to attribute a psychology to him would be foolish, he is already an instantiation of psychology.”

Michael Gambon in The Singing Detective, 1986.

The psyche is, in other words, a theatre space. A stage. It may not really be possible to grasp what those cave painters were doing thirty five thousand years ago, and it maybe very difficult, finally, to grasp much of Dante or Cavalcanti or even Chaucer. It is interesting, at the least, to examine the role and development of *the stranger* in narratives, and even in paintings, and to then imagine the forced appearance, the necessary stranger who must appear. For he is our first enemy/friend, rival and collaborator. The stranger is also ourselves. The xenophobia and bigotry directed at immigrants or asylum seekers is also a source of pleasure for those most repressed. The bigot’s level of repression is acute and the figure of the ‘other’ (or *Other*, for this is rather contested in a sense..and the pure Lacanian position is perhaps not so clear…but anyway…) is akin to a sighting of something illicit and erotic, to some degree, and also it is the sight of death — of THE dead. The depersonalized stranger, a carrier of plague, of contamination, of that which will invade — both literally through the gates (of bureaucracy today) and into the literal body. But is is not without pleasure. It is arousing. The deeper the repression, the more arousing is the sight of the stranger.

If one were to ask me why I think True Detective 2 is so valuable, my answer is firstly, as Kristeva quotes Veuillot: “to have brothers there must be a Father.” The corrupted aroused death bearing shadow that everyone, all the infected (all of us) carry along in the scarred landscape of post industrial America is one which is almost never simply just presented. The horror is that nobody scolds anyone, to self righteous speeches (well, maybe one) and gratuitous moral signpost — it is the sense of the dammed living out their overtime. Without pay. Weakness and courage are one, self hatred and personal sacrifice are one. Desire is loathing and loathing is desire. The purpose of the story is just to be told.

That is a much more unusual occurrence than one might think.

The ‘desire’ for cliche, for failure, in today’s audience is an expression of the acute anxiety of Western culture. Enthusiasm is distrusted, and the subject position for the audience now has a default setting for ironic detachment. Sincerity is vulnerability. And the perception of narrative that exhibits sincerity or genuineness is attacked in that way the most vulnerable are always attacked. The inoculated artwork, the ironic and that which parades its lack of integrity as fashionable, for nothing is so fashionable as exclusionary insincerity, are praised for cleverness and facility. The sincere is received as weak, as crippled and the pack attacks it. Cynicism now permeates all corners of the political spectrum. The other aspect of this is the demand for wholeness. For completion. Artworks, especially narrative art, is judged by how tidy is the *whole*. True Detective 2 is a deeply flawed series. There are lapses in tone, melodramatic exposition, and yet, these failures are more a sign of how right are those parts that succeed. One need only look at the concluding episode of the critically acclaimed Mad Men and compare it with the final episode of True Detective 2. There are even parallel aspects in how the 60s and *hippie* communes are treated. One is examining the loss of promise, the impossibility of the damaged society to survive it’s idealistic dreams, and the other is about making a great TV commerical for a cleaning solvent turned soft drink.

Odd. I watched all of Potter’s films, and every episode of The Shield, which might be a kind of precursor, but I couldn’t get myself up to watch True Detective. I think I’ve always distrusted cynicism, as something verisimilitudinally false. This goes back to my youth when I listened to Lenny Bruce albums and decided I didn’t like the people who liked them.

@kevin:

well, i agree about cynicism. Which as adorno said, is just another mode of conformity. But I dont think Lenny or his audience were cynical and what makes you think TD2 is cynical? Its not cynical. But a couple other people have mentioned The Shield, which I thought was a strange network mainstream attempt at being edgy. It was so self consciously *edgy*. It felt like a middle aged bald guy in his corvette.

Some who had watched the first season and felt duped when they realized that the show wasn’t a pulp thriller after all, but a piece of psychological archeology, were already gunning for the second season.

For others, the show’s very seriousness was an affront. It simply had to be taken down for daring not to be preemptively ironic. The code word for this in review-speak is ‘pretentious’.

@ Beckner…..exactly so. They were gunning for it, such seriousness is not allowed…its too accusative .