Rona Pondick

“The unconscious too easily appears to be a thing we speak about, while actually it speaks in its specific way and with its specific syntax.”

Octave Mannoni

“And how can one be sure, in such darkness.”

Beckett

“The Unnamable”

“The problem for critical thought, now, is how to make reality break in on the mind that masters it. For what we are involved in, that’s the one praxis. And the puzzle of this praxis is shaped in realizing that while reality must be made to break in on the mind, that can’t occur in the model of tossing a stone through a window; the window must shatter under its own fissuring tinsel pressures, from within, as a violence against the violence.”

Robert Hullot-Kentor

There are many reasons, it seems, that certain images attract our attention, and for fewer, keep our attention. I recently came across some photos of a building in Westphalia, Germany, designed and built by Ortner & Ortner architects. It is the NSW Archive, which is, strictly speaking, more of an addition. It is a large brick tower (containing, we are told 296 miles of shelving) that erupts out of an old brick silo/building, looming over the small riverfront area in Duisburg. It is (along with Poelzig’s acid factory in Lublin) the most uncanny of buildings. It is a dream building. There are no windows. It is oddly proportioned to the rest of the extant structure, and it is, oddly — perhaps, made of brick. There is something haunting in the sheer volume of the face of this tower, each side of it. I can think of few structures of this scale that lack any windows.

NSW Archives, Duisburg, Germany. Ortner & Ortner architecture. (Nils Koenig photog.)

But as I reflected on this building I realized that blankness is often the most compelling, and uncanny, of elements in architecture. Walls, and broad empty surfaces in any context, are always slightly disturbing. One of the things I love about Barragan is that he featured walls. Often pink walls, but its more that they are never decorated or adorned. Islamic architecture often juxtaposes ornate decoration of surface with emptiness. This quality, the expansive sense of limitless abandon is found in other mediums, in what might be seen as equivalent forms. But it is not so simple as I am describing; for many blank surfaces on buildings are just the stuff our eye passes over. Now, it is worth considering the idea of windows and what it means to not have any. For there are windows and there are windows. I think perhaps the design of windows is the most difficult architectural element to get right. Personally I think modern buildings have far too many windows. If you visit ancient structures, monastaries and castles and cathedrals, there are no random casual invitations to look inside. Nor are there the refused invitation of tinted windows or shuttered windows. I have also always loved clerestory windows in modern architecture; especially in homes. The original use of clerestory windows in Byzantine architecture, churches most commonly, was to illuminate a large room by allowing in light from above the neighboring roof line. In Catholic Churches the clerestory window was used to illuminate an area separating nave from side aisle. Often small quatrefoil openings were all that permitted in light, but the idea goes back, really, to Egyptian temples, though in another form (theoretically speaking). Partini, when restoring the Cathedral of Siena, sought to guide the parishioner’s eyes upward to the celestial light of the clerestory window openings.

NSW Archive, Duisberg.

What separates Romanesque from Gothic, more than anything else, is the light. The focus on controlling luminosity. Clerestory windows were linked, also, in medieval thinking, with the inability to see the ground. I bother to mention all this because it is linked to this idea of the blank architectural plane. The empty wall. There is a difference between exterior blankness and interior. And it is worth considering in what ways windows and their control of light describe boundaries for inside and outside. The spatial models for our psyche integrate the window, the aperture, as a way to make sense of subjectivity.

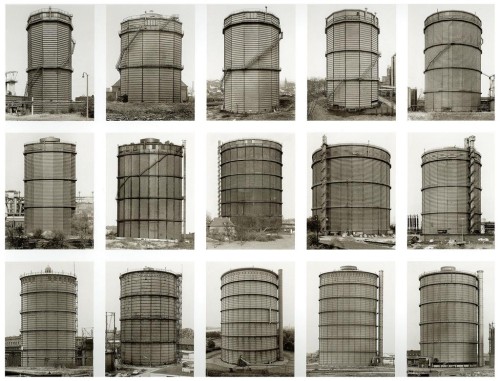

There is another aspect to this aesthetic removal, and it has to do with the implications of a missing subject. There is a paradox here, though. In Hilda and Bernd Becher’s photographs, which have been hugely influential, as has their teaching, there are no people. Not only are there no people, there is a peculiar renunciation of subjectivity. This is a contested area, however. Sarah James writes; “In the Becher’s photography, the situation of the speaking subject is rejected in favor of the more generic statement or archive.” I am not sure this is entirely true, however. The Becher’s project has been to present their subject (industrial buildings of various sorts) in grids, with the implicit comparison of small differences. A focus on both similarity and uniqueness. H.D. Bulloch saw their work as a denial of the social, and a return to some version of the picturesque. But it is neither, really. The denial is of the individual subject that is author, but it reinforces an idea of the collective. The Becher’s work is presented, as well, to be read…its typographical. In that sense it is close to film. However, it is clearly not what critics like Blake Stimson suggest when comparing it to Steichen’s Family of Man project. Of course, the author is never really removed. But what interests me in this debate is an aesthetic that presents an implied social. An implied collective. These are, regardless of the seriality, objects of industry. They are relics of a society. The removal of Nature, in the lack of geographic specificity and place, then forces the viewer to regard not just this missing frame, but to (per Stimson) to see “a symptom of a social relation”. The specificity is where the artistry enters, and in this specificity there resides something of a genuine sense of collectivity in the audience. Michael Fried, who James quotes, refers to an “aesthetics without aesthetics”. This is where I think returning to the NSW Archive building is useful.

Helen Binet, photography.

The Becher’s are recording something architectural. But it is the architecture of industry, of Capital, and their work coincided with West German cultural promotion under Adenauer. In film, this was the era of the Oberhausen Manifesto (1962, which is actually half a decade after the Becher’s actually began their project). Twenty six filmmakers signed the manifesto, sort of circling around Alexander Kluge. The Neuer Deutscher Film, which was mostly the *children* of the Manifesto; Fassbinder, Herzog, Wenders, and Syberberg, were highly active from the 60s onward. The point is that what the Becher’s were doing was inscribing something specific about the grammar of Capital. In fact this is what, in varying ways, the New German Cinema was doing as well (more on that below). It is important to look at the NSW Archive in light of German art after WW2. The desire to remove ideology and by extension to remove a kind of kitsch *identity*. Adorno saw identity as the repetition of the same (to be reductive) and here is where the uncanny aspect of the NSW building enters the discussion.

Cathedral of Siena. Construction started 1215.

The NSW Archive is both disturbingly uncanny and dream-like, but is so, I believe, because it is archaeology and almost allegory. The great windowless column, or obelisk, rests on its plinth, or pedestal; a far older brick silo. It is this sense of thrusting out of the older industrial silo that gives the Archive such a disturbing quality. Adorno’s ideas on mimesis are relevant, here, too, but first I want to think more on the idea of the blank wall, on an idea of removing the conceptual comment. Post modernism is also relevant because of this idea of problematizing the referent. With the NSW Archive, this idea is itself problematized. Now art, including architecture, must, to be art, be presenting or saying something impossible. The final reality is always the impossible and the NSW Archive is an impossible building. The fact that it is, functionally, a storage facility, is mostly beside the point. But all aesthetics imply something of an unresolved origin question. This is both Freud and Adorno, and probably Hegel. This is what regression is, really, and certainly if I’m at all right about this idea of blankness, then it is that which draws the viewer more acutely into this troubling vortex of regression. And like the off-stage in theatre, this building asks the viewer to imagine what is inside. And the answer is; the unconscious.

“The more life is submerged, the more it needs the artwork, which unseals its withdrawnness and puts its pieces back in place in such a way that these, which were lying strewn about, become organized in a meaningful way.”

Siegfried Kracauer

Construction of Washington Monument, 1860 (Mathew Brady photography).

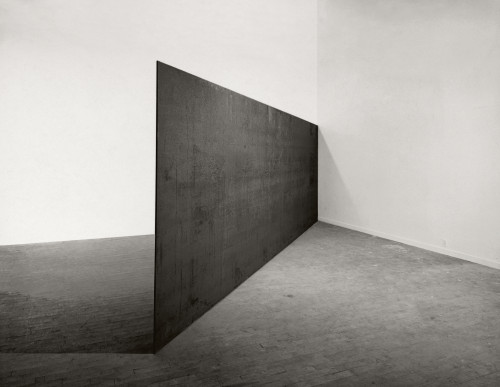

Richard Serra

Regression is something that intersects with aesthetics in more profound ways than are usually investigated. The sense of identity is directly linked as an active part of the construction of all aesthetic experience. But identity is impossible, really, to define. What can be defined are the rituals of identity, and the repetitions of the same demanded to hold onto this idea. The lobby, or the grounds of the Capital lawn, or the waterfront surrounding the NSW Archive are not really community spaces. I would alter Kracauer by saying the Church is an inverted Hotel lobby. The occupants of the lobby are there in relation to no governing principle other than transit. And yet, the rituals and protocol of hotel lobbies, even today, is one of stripping away character the better to homogenize, but to also create illusions of decorum and attentiveness to the paying guests. To strangers. In the lobby, the stranger is accorded respect, or the facsimile of respect. The rise of tourism is a topic worthy of an entire posting, but it certainly is more and more shaped by the rules of subjugation, class hierarchy, and colonization. Leisure time and vacation are now overdetermined exercises in the imitation of labor and in submission to the idea of an ersatz privilege. The doorman is the symbol of white privilege. That so many bell boys and doormen are people of color is hardly accidental. But I digress. The blankness of regression; for under it all I believe the uncanny and compelling experience of certain empty walls or building facades is one with the nature of regression.

Regression has links to the morbidity of group-think, group psychology associated with fascism and authoritarianism. It undoes, temporarily, the maturation that is working toward autonomy and individuation. Regression shares a good deal with the uncanny, as well. Robert Hullot-Kentor points out (in discussion Adorno’s concept of regression) that both *arrive*, and with a certain familiarity. Regression is always a returning of something. Something uncannily familiar. It is important to remove certain linear or spatial models when thinking about regression, because it has nothing to do with travelling back in time, but rather with unresolved tensions and conflicts manifesting themselves (again). The return of the repressed. Adorno saw that the administered society had encouraged the public to discard discrimination and to replace it with vague terms (like, enjoy, etc) that really meant ‘familiar’. The most familiar quality is repetition. People will laugh at jokes told in a foreign language if the rhythm is familiar. They anticipate the punch line.

Nadyev Kanter, photography. (Polygon Nuclear Test Site, Kazakhstan).

“You will scarcely be able to reject a judgment that the philosophy of today has retained some essential features of the animistic mode of thought—the overvaluation of the magic of words and the belief that the real events in the world take the course which our thinking seeks to impose on them. It would seem . . . to be an animism without magic actions.”

Sigmund Freud, “The Question of a Weltanschauung”

The obelisk, and the blank facade, are missing the familiar. We have no word for what is missing, other than to articulate in some fashion an experience of UN-familiarity. But that experience of unfamiliarity is something very close to uncanny. It often is, strictly speaking, uncanny. But here the ideas of repetition, of regression, and of origin need to be discussed. Helen Cixous discusses the symbolism of Oedipal theory – that it is always a fiction, a symbol. So, the memory is dislocated, and that space between absolute unity of event and memory is part of what creates the uncanny as a sort of resonance. Perhaps, and for me it doesn’t really matter so much because everything we experience is dislocated to some degree. Aesthetics, the mimetic experience, is always about hidden tensions and unresolved conflict — partly. An unconscious historiography. But here, remember, that primal fantasies, primal crime can only be acted-out, not remembered. The memory of what is a fiction is only the source for more repression. But the acting out is involved in the creation of art. Or, in an aesthetic ordering of the world around us. Now, if man is both (as I suspect) aggressive AND cooperative and loving, then it is the imposition of authority and control that derails the impulse (as Norman O.Brown says) of *losing* things. The impulse for gift giving in early pre-modern socities. For sacrifice. Gifts to the Gods. Nobody needs a God, perhaps, except as someone for whom one can give gifts.A symbolic and literal unburdening.

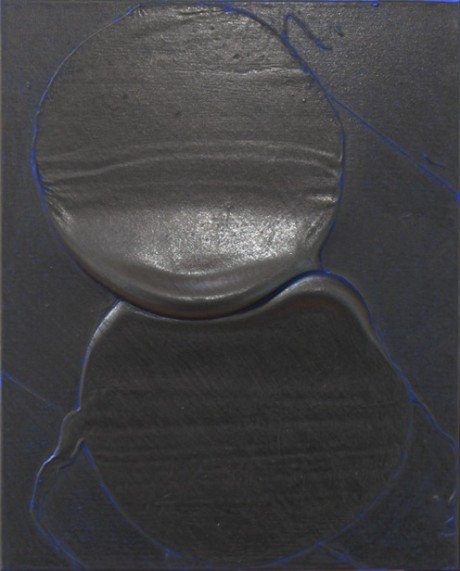

The missing familiar is not quite the same as the unfamiliar. In narrative forms, the missing familiar is the center of what Kafka was doing, I think. In The Trial, the reader is familiar with the world of the judicial, with bureaucracy, and yet, there is something that normally would provide stability to this story. One might simply say the elliptical is what I am describing, and that is partly true. But not entirely. In theatre, Pinter creates something on stage that is familiar, but it is all the time suggesting we look elsewhere for the real problem. Something is missing. Something has left. In theatre, the equivalent of the empty architectural experience is linked to something the audience senses has just left. In painting, the sense of a missing familiar is linked more directly to technique, I think. The traces of the painter’s hand, the brush strokes, the application of pigment. Or, the lack of filling up space. Everyone from Morris Louis to Toba Khadoori are operating with a keen awareness of what hasn’t been touched. Classical Chinese painting was certainly examining something left out, but more purely in the geometry of negative space. In Chinese painting the feeling is of what is to come, of what might momentarily appear, rather than what has recently left.

Takesada Matsutani

The Lacanian notion of the mirror phase explains a first dislocation, the birth of suspicion. And it is interesting to look at this in light of the idea of infant dreaming. The dream of loss, and of lack. To bring this back around to that blank wall again, the resonance or uncanny experience of such unfamiliarity is a forgotten memory of suspicion. Of theft. The mimetic is imitating or re-narrating something impossible, for there are no characters, no characteristics even. The photographs of the Bechers are telling a primal story of both suspicion, and loss, and of sublimation and authority. The blank facade is also a vertical stage. The NSW Archive is of course also a phallus, and a good many other things. It takes on meaning because it doesn’t belong where it is, and because it is secret. It is one of the great secret buildings of recent times. Its secret is conspicuously out in the open. It is exhibitionistic in its secretiveness. It is also, those towering empty brick facades, suggesting the need for something. Why is it not marked? Architecture is the artform most mediated by Capital (in the modern era, anyway). Opportunism is the disease of the young architect. The growing body of evidence on Le Corbusie and his fascist sympathies informs, like it or not, how retrospectively we view his buildings. And it becomes clear, even if much of his reactionary association was opportunistic, that the purifying of the eye was all too close to exterminationist sensibilities. The idealization of ancient Greece and an imaginary antiquity is the hallmark of fascist aesthetic thinking, and Le Corbusie was certainly in line with this kind of fantasy, one always close to a certain anality and sanitizing of self. The fascist is always looking at the impurity of the world, which is always really a self revulsion and ambivalence about their own body and sexuality. The clean white walls of Le Corbusier were doing several things at once, though. And one of those things was to create large open windows. Transparency was really a fuliginous emotional interior. Bodily ambivalence is expressed as domination, and sadism. The paradox in Le Corbusie is that the desire to cleanse became self discipline and restraint. His application to work in the U.S.S.R. (which was rejected) suggests ideas of massive organizing of people appealed to him, but only if purified first.

Li Sixun (Li Ssu-hsün ) Northern Tang Dynasty. 651-716.

There is always a doubling effect in artworks. Recently, in The New Yorker, Nathan Haller wrote a fluff piece about modern *creepiness* (this is The New Yorker brand at work, pseudo high brow cocktail chatter). He says nothing very interesting except for the fact that he, the author, emerges as the creep. It ends up, unintentionally, as a confession of sorts, but unconscious. Helene Cixous pointed out that to speak of castration is to castrate or cancel the effect. While this is not entirely, literally, true, it is in principle correct. The audience is always the double of the author or artist. But the author is also doubling something else, or serves, in effect, as the ventriloquist’s dummy. By which I mean that there are two things at work in all this. One is mimesis, and the other is repetition. But as Anneleen Masschelein says, the repetition is never exact. This takes us to a third factor; the revealing of the present. This would be how Benjamin saw Tragedy. Now what is returning…in this return of the repressed, is only a recurrence of a certain unresolved conflict. That which returns is, in all cases, always something new. Haunting all this is Death — but death means many things in this context. It means trauma for one. But in the society of domination, under a system of constant coercion, that which *arrives* is mediated by history. Everyone is sick. The universal neurosis of mankind (Freud). In the contemporary West, there is now a society of acute isolation amid a presentation or representation of togetherness. Proximity is not unity. So there are two fronts here; one is a compensatory disfiguring of how people read their isolation, and a fear of solitude. For the ruling class, there is a constant fear of potential unity in the masses. So much of the random almost casual sadism of society is driven by ruling class and their walking nightmare of unification from below. But I digress, slightly.

Written on The Wind (1957). Douglas Sirk, dr.

Mass culture, meaning corporate owned electronic media, Hollywood film and TV, are both extracting as much profit as possible while at the same time offering empty promises to reduce anxiety. Entertainment as a concept is about anxiety reduction. Samuel Weber makes a terrific point about *commercial breaks* in TV programming (something which is, however, changing because of how people record and watch their *entertainment*). Weber: “The commercial break exploits the anxiety associated with far more drastic breaks to come. In announcing the commercial break the television speaker enjoins the viewers to ‘stay with us’, assuring them that ‘we’ll be right back’.”

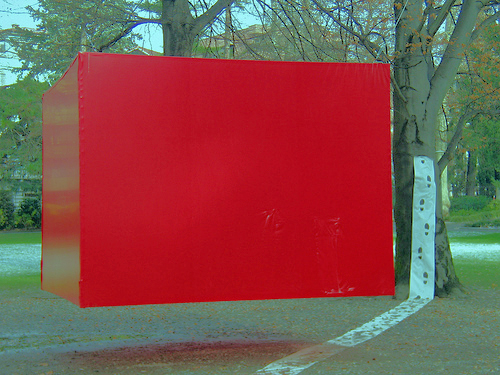

The audience is made to feel inadequate if they fail to respect the call of the programmers. The audience is also, however, treated as an intimate. A friend. When Benjamin wrote that the orchestra pit separated the living from the dead, Weber suggests the commercial break is doing something very similar. The conditioning for interruption is intense, now. TV series are cancelled in mid story. There are ever more commercials and branding associated with pop narratives. This is a bit like Heidegger’s notion of everything being put on standby. The standing reserve. In mass culture everything is geared toward staying the same. Except not totally. As Jean Luc Godard said, “its all the same, just a little bit different.” So, the fact that all repetition is inexact, the constant drumbeat of sameness creates fissures in how audiences process their own subjectivity in relation to artworks. The blank facade then, is something unacceptable for commerical film and TV. In contemporary art, it appears, but only, or usually, as a false blankness (more on that below). The unmarked wall, or facade, or screen, is connected at a primal level with our earliest sense of distrust. The enormous growth of signage in Capitalism is reflective of making sure spaces are marked. The wall, unmarked, or the obelisk, always hides a memory of abandonment. Of loss, and a reminder of our own amnesia. Without markings, without the superficial authorship of a message, the uncanny effect reproduces a forgotten trauma. Or, it may even stimulate thoughts of death. Also, the idea of *newness* is automatically a reminder of antiquity and pre-history. The idea of the new is linked to ideas of exile and wandering. Traditional communities that carved out some form of stability had little interest in the *new*. The exile is driven from ‘home’. The earliest wandering nomads linked death to place, to permanent dwelling. The dead stopping moving from one place to another. All of this is there in the unmarked space. Where did the tradition of burial markers come from? In societies favoring cremation, there was still the understanding that travels had come to an end for the one now dead.

Alberto Burri, “Grand Cretto”. 1980.

Norman O. Brown, writing of the pyramids:

“Death is overcome on condition that the real actuality of life pass into these immortal and dead things; money is the man; the

immortality of an estate or a corporation resides in the dead things which alone endure.”

Hilla & Bernd Becher, photography.

Roman law introduced the formal relationship between material wealth, and property, and a desire for eternity. Compare the hotel lobby to a major train or bus station depot. The quiet of the Church was once mirrored in hotel lobbies, at least in higher end examples. I am not sure that’s so true today, but still, a removal takes place, one is taken away and off ‘the street’. Sanctuary. But today, the coercive nature of advanced capitalism has rendered sanctuary extinct. CCTV and various other surveillance techniques are now employed at even lower end hotel and motels. Streets themselves are awash in surveillance. This loss of sanctuary is exactly reproducing the loss of habitat for much of the world’s larger mammals, and birds. One cannot be controlled completely, in the same way one’s memory is incomplete, and the memory that IS there is faulty. Throughout all of this the very idea of the *insterstice* has become important.

The insertion of noise, today, is another action in service of class segregation. The wealthy buy quiet.

Jiro Yoshiharo

The idea of the street, of course, has changed. The representation of the street, in urban contexts. Today the street is marketing (in the West, for the streets of the Medina are quite a different experience). The mall is only an indoor street. A simulacra street. The act of shopping takes place there, so why would you need sanctuary? Sanctuary is for weaklings, the soft, the impaired. At the same time, the street is a jungle of black and brown crime lords, mastermminds, and gangbangers…initiating sadistic rights of entry into their secret societies. Societies that still form the bedrock fantasy fear for white america. The image of the very young black urban dwelling male, pre-puberty usually, is there as the figure in need of rescue by white men. Like Arab terrorists, Hollywood and media must merge contradiction: both ruthless predatory animals, living in caves or squalor….OR/AND…evil masterminds, cunning, efficient, Capos and overlords. Both-and. But this is perfectly understandable in the doubling of any representation. But the representation of the street is probably the most acute fiction in contemporary society. It is often referred to in narratives as if it is a place, especially in police drama where ‘there is no word on the street’. This non-place is simply a plot filler. But its resonates anyway because it echoes the white centered world view.

“My work also returns to politics. I would like to do a poetics of politics, a poetic approach to the

structure of civilization.”

Norman O. Brown

Another sort of secondary effect in how space is securitized is the ways in which sexual repression is normalized, and how Marcuse’s repressive desublimation is actually, today, more like a doubled version of that. The society of titillation — is actually doing two things at once. It is a constant stream of sexually charged images and nudity and at the same time there is a cleansing action applied to these images. Rihanna’s image and videos are a good example. Her manufactured sexuality is actually very clean, shiny, smooth, android-like. The signifiers for sex are there, for a kind of porn sex, but this isn’t even masturbatory imagery. It doesn’t even rise to that. And the conflating of the lyric message and the image message, as it were, merge to be just another simulacra of non-world space. Faux sexual and faux political and faux social. The fact is that representations of violence are far more pernicious in mass media than sexuality. Violence IS sexualized. Sexuality is made artificial.

Tamas Dezso, photography.

The blank is colonized by high end fine arts, as a concept anyway. Or there is an attempt to do this. The uncanny, as has been said before, cannot be planned. It appears, it arrives. It is not manufactured. This is the very problem with David Lynch and Robert Wilson and Cindy Sherman. There is nothing missing, and in fact there is too much. But the actions of corporate culture and its subcontracting of prestige fine arts, are working to stop memory and contain and corral experience. At least aesthetic experience. The theatre audience is dangerous because it is not the hotel lobby or the church. The movie audience is increasingly dispersed, and this encourages the sense of false individuality. The paradox, if that is what it is, is that the blank facade or unmarked space is a link to collectivity, to a social totality. But this perhaps needs further discussion. For it is not a direct link. Today, in the West, the constant 24 hour a day image stream is there to make sure everything is marked and inventoried. The unmarked as it arrives is ‘not in the system’. One cannot locate it because there is nothing to locate, only an experience that triggers a long series of actions, emotions, and mimesis. As Adorno says; “Nothing social in art is immediately social, not even when that is its aim.”

“The task of aesthetics is not to comprehend artworks as hermeneutical objects; in the contemporary situation, it is their incomprehensibility that needs to be comprehended.”

Adorno

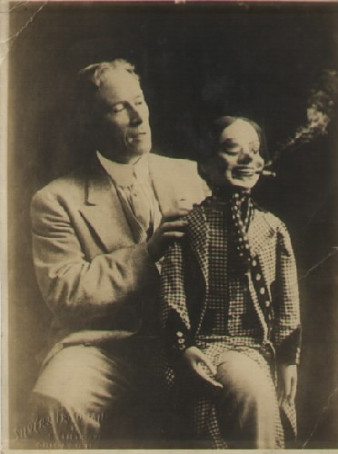

Unknown ventriloquist and his dummy. Apprx 1910.

Now this is why artworks that intend a spirituality always fail. Mimesis is, for Adorno, pre-spiritual (although, more in the Hegelian sense). Today, there are increasingly rigid codes of meaning produced by mass culture. They serve to silently send a message to their intended demographic. The dog whistle phenomenon, which was practiced in crude form by Reagan. And one of the meta-codes is the cleansing action. The cleansing of sexuality implies a further deeper cleansing of emotion in general. Of doubt, of reflection, and of collectivity. The action that modifies the mimetic action is in effect a regulative mechanism for dreaming. The degrading of language is a crucial part of this, for dream formation transfers much its work to the verbal. The dream is creating an alternative stage. Freud no doubt over-simplified the actions associated with the imagination and with creativity, for here again the concept of origin intrudes. We create in conjunction with words and grammar, and art is not simply the satisfaction of unconscious wishes, for those wishes are themselves only another level of dream. These cleansing actions are often, if not usually, on auto pilot — the cleansing is a sort of feedback loop. As long as the end result is to impose the false blank. The shiny surface of mock sexuality, mock seriousness, mock political. And mock uncanny. This is the post modern surface. But it is not really blank. It is marked with the cleansing mechanism of dilution and homogenization and it has overtaken repetition, in a sense. This process of imposition on our mimetic narration is multi-dimensional, and traffics in both the degraded meaning of words, and in a shrunken sense of poetics, but it instills a familiarity with and approval of abnegation…for the panic felt by the dislocation from absolute sameness must be pacified. So the process is repeated, quickly, to stave off the durational effects (potential) of this fissure or crevice of feeling and experience. For in those crevices lurk the impulses to question authority. Now, there is no *content* to cleansing — to this action. Or rather, the content is so stripped down that it appears transparent. And, there is yet another sort of paradox that involves the idea of blank or unmarked. This idea of blank is one of experience. The blank is instantaneous but it also prolonged. It haunts us. The blank wall is not empty. It is simply not labeled. The artist might fill in space, if its a painting, and yet that painting may never register as intentionally worked on. Part of this has to do with the fact that art is met with astonishment, with surprise, not with surveys or conceptual interpretation (although I know many leftists who do exactly this). Tolerance for bad art, Adorno said, was a violation of art. In any event, the blank is equivocal. One blank might be quite marked up and another not. The one that is experienced, intuited if you like, that resists the whole, is the one that is not immediately re-integrated. Now this is obtuse, but perhaps in another way, the idea of cleansing, will make it clearer. The meta code that removes genuine sexual energy, is one that denies subjective ecstatic feeling in the name of some morality or other, but which is really just domination. The recognition of one’s own subjugation is deflected and incorporated into a reading of signs and signals in a Rihanna video, or CNN news program, or any mass produced corporate noise. The evocative shudder that arrives in the face of the uncanny, or of the less determinate blank space, is — just because of its erasure of the subject — exactly by that fact, it becomes something social and communal. An abrogated *I* becomes a possible *we*. The *we* as shelter. The role of irony is connected to the exaggerated explanations that accompany interpretation on an immediate level.

Ignacio Uriarte

Edward Said writing of Norman O.Brown…“If for him “the body is a body politic,” and genital organization is the tyranny of the genital over the other organs, the conventional literature and criticism with their fairly rigid habits of special pleading and exposition, are genital monarchs over the body of language.” This is interesting here because aesthetics is always political. Aesthetics, or art, is always a gesture against domination and control and inequality — but it best achieves this by indirect means. The ego is our first property, an object but always a false object. As Lacan said; “an odd puppet..a baroque doll…a trophy made of limbs in which must be recognized the narcissistic object whose genesis we have cited…” The marionette and puppet are so disturbing and enticing because the doubling effect is so pronounced; we are seeing ourselves. The ventriloquist act is one of pure dislocation, and uncanniness. And to look at vintage photos of ventriloquist acts is a remarkable experience for it speaks to this cleansing Puritanism of mass culture. The dummy in the early ventriloquist act was often dark and perverse, menacing and anti-social. There is, today, in cultural presentation a de-facto alibi attached to every experience. This is both the legacy of instrumental reason, and an aspect of the permission granted to not take anything seriously.

“There is no denying that the antagonistic condition Marx called alienation was a powerful leaven for modern art. However, modern art was not simply a replica or reproduction of that condition but has denounced it in no uncertain terms, transposing it into an imago. In doing so modern art became the opposite other of an alienated condition. The former was as free as the latter is unfree.”

Adorno

Seeing ourselves and triggering that memory that cannot ever quite be reached. But it is a troubling memory, anyway. The gaze is always suspicious, and when presented with that which is outside the system, it recoils in fear. At first, because this is what domination has done. This is precisely the place at which the full nightmare of Capitalism and exploitation, of coercion and manipulation is felt, on an emotional level that signals the inescapable reality of our isolation from not just ourselves, but each other. That we are all colonial subjects, finally. And behind this coercion is the figure of the corpse. The only figure not exiled, the only one truly home.

A final thought on the New German Cinema of the 60s and 70s. That their favorite director, if one could be picked, was Douglas Sirk is not surprising. Sirk’s cinema, as Cahiers du Cinéma put it, was *impossible*. Sirk was a pivot point for modernism, and his films both look forward and look back. There is a deep malaise in Sirk that connects to his awareness of how tawdry his material was, and how sublimely he treated it. In Sirk, as in Fassbinder and to some degree in Syberberg, the grammar of Capital is being autopsied. Sexuality and desire are distrusted and yet embraced. Sirk was always missing the familiar, even amid the most trite melodrama, he introduced an idea of alienation. And perhaps that blank architectural uncanny is really a distillation of contemporary alienation. But a distillation that points toward aesthetic awakening, and resistance.

As always John, a very compelling read. In any case, I was a bit confused about your statement regarding artworks failing if they intend a spirituality. In that case, there are many important artists that one would have to write off. I think it’s a bit more complex than that, and it depends on the culture from which the artwork is emanating. Russians and Poles for instance I think are quite “spiritual” peoples, so I think many of their artworks will reflect that. Andrei Tarkovsky would be a strong example of an artist whose works do intend a spirituality, but I wouldn’t say they necessarily fail, although the mysticism can perhaps seem a tad facile on occasion. Likewise Mizoguchi whose films are often considered transcendental.

The French on the other hand aren’t particularly ‘spiritual’ at all, which I think explains why their strongest artistic contributions have a pronounced sense of physicality that you’re not going to find in Kafka or Tarkovsky. But in either case, isn’t that a large compenent of mimesis, aspiring to a sense of physicality, providing the aesthetic object with materiality I guess you could say, which I don’t think precludes the uncanny element.

Now I’d also argue that the epics of Homer do indeed intend a certain spirituality as well, due to the obvious influence of the Gods in orchestrating certain events that occur within the narratives. In much of the literature of antiquity there are explicitly stated supernatural elements.

@remy,

I think you are mis reading what Im saying. Clearly many artworks are *spiritual*….a word I have a problem with, in any case. But work that consciously looks to impart something spiritual tend to fail. The same as intentional uncanniness. The spiritual I think…whatever that is…happens almost as a byproduct. You can’t just manufacture it as a primary goal. Its funny when I wrote that sentence I almost changed it because I have such difficulty with that word. It carries a lot of baggage with it. The national character of works is complex — and Id probably just say the french , or whoever…..have another sort of spirituality. I do think russian work, for example, tends toward a certain fatalistic sense of life, a tragic vision that seems to be there in almost everything that comes from that culture. But I dont think they all look to be spiritual. Im not sure even tarkovsky is really interested in that, per se. But as i say, its a big topic.

Well that may be the issue, the semantic ambiguity of the word ‘spiritual’, since the typical assumption is that it relates to anything that tends toward mysticism. Then again, ‘metaphysical’ is also a rather murky term. So the question what do these words mean, and what does metaphysical art entail. Can art that’s heavily invested in the flesh rather than in the ‘spirit’ not be metaphysical? I would say it can be, but as you say, it’s a big topic. I think many are skeptical of the metaphysical in art, not necessarily for reactionary reasons, but because they’re suspicious of anything that tends toward mysticism, because it doesn’t reflect what they see and know. They see and know the flesh. They don’t know the ‘unexplained’.

One other thing I’ll say is I hesitate to nationalize art, in a sense, attempting to categorize every work art as the extension of a certain national psyche. Surely those Dostoevskyian themes revolving around disaffectedness can be applied to plenty of people living in Western countries even today. So an American or a French person should certainly be able to find inspiration in similar ideas if he or she chose. I don’t think the archetypes embodied by say Alyosha or Raskolnikov are uniquely Russian. Rather, Russians for one reason or another are drawn to such tragic existences.