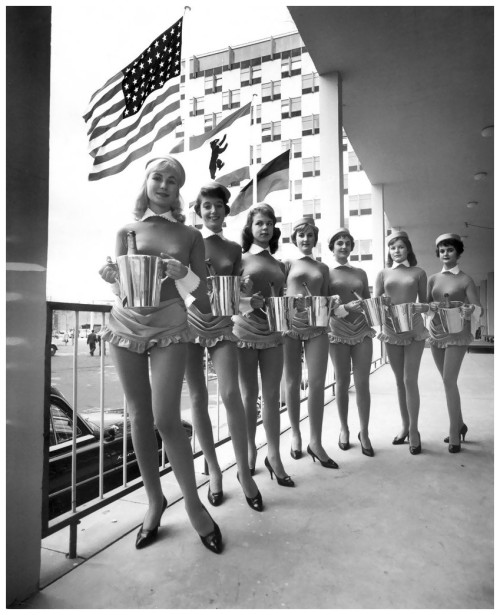

F.C. Gundlach, photography. Berlin Hilton, 1958

“..the fundamental meaning of symbols in which the earliest human beings customarily deposited their views of the nature of the world around them is purely physical and material. Symbolism, like language, sat in nature’s lap.”

Johann Jakob Bachofen

“Departure in dreams means dying.”

Freud, Introductory Lectures

“Seems, madam? Nay, it is. I know not seems.”

Shakespeare

Hamlet

I think that the critical response to the premiere of the second season of HBO’s True Detective reveals a lot about mass culture at the moment. Not just that they were negative, but were near unanimously violently negative and snarky. Now, many critics had watched the three episodes provided to critics, while the rest of us have seen only the first episode, so bear that in mind, I suppose. But I think as genre television goes, this, like the first season, is about as good as it gets in studio/cable/network series. It is baroque, and dark, and the landscape, as was true in the first season, is one of pathology and poverty and despair. The narrative is highly elliptical and the main characters severely damaged. The locations include an LA county city named *Vinci*. This is a stand in for Vernon, California. And one of the interesting aspects of this season is that Nic Pizzolatto chose Ventura County, Salinas in the Central Valley, and Vernon as the locations to tell his story. They are the geographic reflections of the damaged characters. Vernon is a small industrial incorporated city next to City of Industry and Huntington Park, in the industrial corridor near downtown L.A.. Officially Vernon only has about 100 residents. City of Industry has only 250. Both are essentially industrial locations, with Vernon in particular having a century long history of corruption and back door deals. In fact there were no elections for thirty years in Vernon. The mayor and his assistants were just handpicked by the owners of the industries within its borders. The only voters in the city are city employees, or employees of the city of Los Angeles. In 2009 Leonis Malburg, the mayor for fifty years was convicted of voter fraud, conspiracy, and perjury. His city administrator pleaded no contest to misappropriating sixty thousand dollars.

City of Vernon, CA.

Vernon is home to a number of metal working shops, meatpacking, and food services. It also has a police force, a notoriously strong armed one, and a Class 1-A fire department equipped to handle dangerous Industrial and chemical fires (one of only a handful so designated departments in the U.S.). For power the city had, up until 2005, used a generator that pre-dates WW2, and several generations of migrant Latino workers toiled in the huge stone building that was using diesel turbines built in 1933. These anachronisms are typical of this small fiefdom in the middle of south east LA. The original founder was a Basque immigrant whose family still largely controls the city. This is the starting place for Pizzolatto’s noir drama.

Critics today, in the mainstream, are largely white, University (badly)educated, and most are young. It’s not like one can raise a family writing film reviews. And why anyone, including myself, calls these hipster hacks *critics* is beyond me. They are the flotsam and jetsam of English departments across the U.S. And usually, today, the reviewer does double duty as the *celebrity* reporter. The, uh, gossip columnist. One without an actual column. Mathew Jacobs at Huffington Post holds such a title, “Entertainment Editor”. Mathew likes the new drama UN-real, which is a pretend reality show, seen from backstage, as it were. In the hands of a Michael Ritchie (Smile1975) perhaps, but in fact this show is truly moron level, and tediously shot (and cheaply) and sort of effectively does what real reality shows (sic) do. Mr Jacobs calls it “juicy” (there is an additional camp aesthetic at work with Jacobs). But he loathed True Detective 2. But I suspect this is anxiety in the face of that which takes itself seriously. Pizzoleto believes what he is doing. Now, is this is a hyper masculine story, one featuring cops and cop angst? Sure. There are a host of others problems as well, but there are so many virtues that I’m inclined to forgive it what are, on balance, minor issues.

a young Cornell Woolrich

One of the worst shows in my memory, The Affair, written and created by the wife of a former Clinton aide, won many awards and critics like Jacobs (and I’m not picking on Jacobs, there are a dozen others, and the show won awards) lapped it up. I suspect there are two basic reasons. One is that The Affair features rich white people. And two, there is a built in irony, or at least half-irony, to the whole thing. Its melodrama and proud of it. It’s almost like meta-melodrama, and that, I suspect is the defining characteristic of its success.

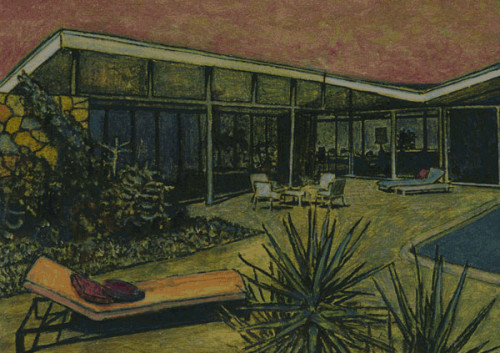

Marc Trujillo

It may well be, that finally, Pizolatto is a very minor artist. It’s too early to say, but I suspect he resides on the more minor side of things. But the dream being created is riveting in places, and the mise-en-scene conveys something fetid and festering. One might compare this with Game of Thrones, another HBO creation. In the latter, the storytelling is rolled out with the trappings of classicism, almost. In fact its just a comic book level bit of sword and sorcery kitsch. It is also, curiously and almost randomly, and certainly gratuitously hyper-violent. In the third season, a little girl with a disfiguring skin disease, has been trolled to the audience for the entire season, as the personification of innocence and virtue. Then she is burnt at the stake by her father. Why? Because a witch(ish) sort of Supernatural lady Macbeth character deems it a necessary sacrifice. Why necessary? Ah, well, um, you know….because she is bad. Bad people do bad things in cartoons. The logic is missing, even by a comic book standard, I think. But it is meant to impart a sense of gravity. It is *shocking*.

I wrote about the demise of modernism the last two postings (among other things) and I just received the new Fredric Jameson book, The Ancients and the Postmoderns. It is worth noting that the first essay in the book, on Rubens, is really about where modernism ended, and more, where it can have begun. One idea of Jameson’s that is quite intriguing, to me anyway, is that the retreat of religion, its evolution into a private matter, arrived via Luther. If so, Jameson argues, then the period of greatest claim to transcendent absolutes, and heightened theatricality, was the Baroque (Shakespeare to Bach). There are two related topics (to me anyway) that are related here; one is technology, and the new screen circulation of image, partial narrative, and data. The other is the sense of the new uncanny that I began to write about last time.

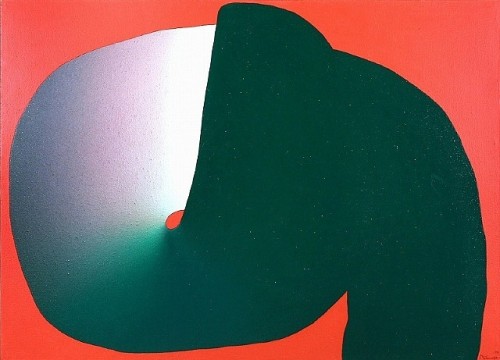

Sadamasa Motonaga

Modernism, in one sense, was, by its end stage, a bit like the Baroque. One significant difference, however, was the rise of textual reproduction, of narrative linked to reading, not listening. Going to the theatre in Shakespeare’s time was an experience of listening, first. Today, the optical priority is evident in all aesthetic experience. But its an opaque optics. It is a form of blindness, and its a blindness to the metaphor or allegory, and to the uncanny. And it is literal blindness of a sort, too. But this also dovetails into the conditioned reception of the educated classes today, especially those under 35. There is a search for snark. The first thing, the first response is always to find the place for derision. The watching of film and TV, the reading of fiction, and even painting, is accompanied by an assumed negativity. It is a fear of sincerity. Sincerity is a kind of weakness, of vulnerability.

Miles Davis pointed out somewhere that all sounds affect musicians. Car crashes today, with plastic parts, sound much different than car crashes in the 1950s. Perhaps an odd example, but relevant. Today the noise of urban areas is on a level unheard of before. But this is also the sort of thing that has been filtered out by the last two generations. The sense of allegorical meaning in daily life has all but vanished. The ratcheting up of security, for example, not only disciplines the population that, say, want to travel; it also makes travel one dimensional and inert. Travel is no longer metaphorical. It is not even meta — today’s average traveler is not engaged in a self interrogation having to do with their life, their goals or lack of them, or even of duration per se. They are looking to minimize their CCTV footprint, as it were, and to avoid problems, of any kind, with authority.

Amy Stein, photography.

“But the wish for genuine connection is

there, and there was a time when the effort, however hysterical,

to assure epistemological presentness was the best expression

of seriousness about our relation to the world, the expression

of an awareness that presentness was threatened,

gone. If epistemology wished to make knowing a substitute

for that fact, that is scarcely foolish or knavish, and scarcely

some simple mistake. It is, in fact, one way to describe the

tragedy King Lear records.”

Stanley Cavell, on King Lear

The wish for connection. There is no longer that desire, not culturally. And because it is absent culturally, and the filtering mechanisms are now so acute, the reactive stance is to deride and ridicule. And in fact this ridicule smacks of the growing infantilism in the culture.

(The hottest selling book last year was an crayon coloring book for adults http://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/30/business/media/grown-ups-get-out-their-crayons.html).

Thinking further on the idea of *travel*: where today the depreciation of experience is evident in just the very idea of departure. For such words have histories. And they evoke complex memories. Suggestive of leaving something or someone, or of arrival, of duration, of being lost, of being found, of becoming this figure ‘the traveler’. For a while, even, the stranger in the landscape. (One of the appeals of driving a car is the perception of freedom from surveillance, a point oddly that seems rarely mentioned).

In the same sense, the loss of privacy, of even the idea of privacy, has eliminated a crucial preserve for people, that *interior* space in which solitude allows another sort of reflection and another sort of *looking*. The approach of adulthood, or maturity, is viewed with the same anxiety and fear. The refusal to engage, the refusal to connect, is mirroring the refusal to grow up. When I say engage, I mean primarily the avoidance of mimetic experience.

Hiros Watanabe, photography.

“The dream factory does not so much fabricate the dream of its customers as disseminate those of its suppliers…In the dream of those who steer the mummification of the world, mass culture is the priestly hieroglphics that provides the subjugated with images not to enjoy but to read.”

Adorno (from posthumously published appendix to Dialectic of Enlightenment).

Adorno says something else, well, two things, in this appendix. He says movie images are grasped, like writing, and not observed. And two, that the increasing onslaught on image, of repetitive kitsch banality means that larger and larger swaths of image and story even, are given the same meaning. Meaning that is self-identical. Over and over and over again. So, even on the most superficial level, the unfamiliar film, or narrative, or image, is either going to be forced to adhere, subconsciously, to previous vetted and accepted meanings, or, it is going to be rejected and erased. It is going to be actively *not seen*. I suspect there is a function now, a psychic function, that is the act of *not seeing*. Here it is useful to remember Wittgenstein’s ideas on application. John Heaton, writing on Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations, wrote…

“We take the words out of their natural place in talking and assume they refer to some essence or ideal entity which we try to define. Because the word is uniform in appearance, we assume it refers to a uniform entity about which we can generalise. We forget the application of the word. Take the word “good”. What is common between a good joke, a good tennis player, a good man, feeling good, good will, good breeding, good looking, and a good for nothing? There is no one common property which the word good refers to.

We cannot analyze the word so that we reach some essence or element from which the concept is built up.”

Diego Velasquez. “The Feast of Bacchus” (1629) detail.

Wittgenstein also believed that philosophy needed fictions. Fictional narration. But he saw that the activity of analysing possibility was very close to the writing down of invented stories. Again words have histories. Wittgenstein did in fact write several remarks on the uncanny. For he saw an importance in ‘home’, and this included in his weird way, language. The home for language, and its double character. It is both familiar and hidden. Both familiar and secret. Now, Adorno sensed that an aspect of mass culture was in a transformation of image into a form of inscription. And that this inscripting carried with it additional effects. And these affects were symptoms of psychic trauma. When I wrote about the trivialization and oppressive qualities of travel today, one of the obvious results was how people turn themselves, out of self protection, into android like anonymity. There is something deathlike in a visit to the airport lounge and waiting area today. It is a morgue, a mausoleum. The readers of mass cultural inscriptions, then, today, are sophisticated consumers of the familiar. Their comfort zone is that of the familiar, and their expertise extends to technical aspects and production costs etc. The package is *read* as the public code for acceptable conformity. It is worth noting, as Samuel Weber does, that Adorno saw that dreaming itself must as colonized as daily life by the same system of image and story production. Both are an inscription, and both are there to make sure people don’t wake up. A public that likely increasingly dreams in symbols and signs and hieroglyphics provided by the corporate owners of media.

Today, mass cultural narratives find success if they take the viewer nowhere. They must go nowhere fast, however. As comical as that sounds. These affects are repeated in political narratives, too, of course. The increasingly absurd nature of network news is a study in almost surrealist comedy. Except of course, the comedy is really a nihilistic death’s head of mass violence and destruction. The normalizing of the military solution to all problems is felt in the role playing of much of the public today. Certainly the endless mayhem of domestic police, their racism and sadism is in part of an acting out of ideal Hollywood action stars. The acting out of an already scripted role for these cops is one that must be repeated, ever more rapidly, however, lest the mask were to slip off and reveal the reptilian grimace beneath.

Augustus Saint-Gaudens. Adams Memorial.

The speaker today, the holder of opinion, is relying on a context that is provided by mass culture. The validity of the meaning is not in some interior experiential state that the speaker accesses. It is not what he or she is experiencing, for there is no context to that other than the same context that the Spectacle provides all the time for everyone. Social media becomes a reflection of this in short hand. Wittgenstein actually maintained that “the contexts of a sentence are best portrayed in a play”. Shakespeare was the great author of interiority. The character reflecting on the hidden interior of the self. And all the way to Beckett and Pinter, this is true. In Greek tragedy, as I have written before, the action is usually off stage. What is *on* stage is language. Is speech. It is a speaking aloud lines written by the author, and rehearsed countless times. The off stage, then, is the interior. That interior, by the time of Shakespeare, in a sense, becomes an inaccessible ‘place’ in the self. But one of the reasons it is so hard to perform Shakespeare, today, is because the context of an individual’s speech in 1600 was created by community. It existed in some relationship with peers. This takes us back to Jameson’s writing on the Baroque. Jameson quotes Maravall that the Baroque was the ‘first great deployment of a public sphere and of mass culture’. But the context for Shakespeare’s interior is one without radio, newspapers, the internet, or electricity even. It is one without even a bourgeoisie.

Stephan Kurtan

It is worth thinking, then, too, about the narratives of painting. The sense of place (a stage?) in Rubens (as Jameson does) or Velasquez or Caravaggio. The self who relies on a world in which the sound of another human voice is exaggerated in comparison with lives today, at least in the urban West, is one in whom the sense of place (home) looms very large. Norman O. Brown, (sampling Arendt) says “to see is to see through. Political organization is theatrical organization, the public realm, where appearance -something that is being seen and heard by others as well as by ourselves -constitutes reality.” But this is no longer quite true. It is cinematic organization today, and social media organization. Such substitute peers or siblings are partial, unsatisfactory (more on this question below) and hence there is an expression of displaced energy that surfaces elsewhere on the psychic map. Surfaces with additional pressure as violence, and finding objective form in racism and colonial thinking, in rituals of punishment, etc. There is a great sense of anxiety in the public today, aesthetically speaking, in submission to story. An immersion in the experience of narrative would mean abdicating one’s expertise in anticipating the direction and conclusion of that narrative. Repetition is interrupted. This also relates to Freud’s idea of revision. The dream work is revised, corrected, in an effort to supply an acceptable *meaning*. One of the functions of all aesthetic acts is to reverse the revision.

Mass culture today has, as one of its jobs, to strengthen revision. It is a form of mass censorship in that sense. The snark attack does several things at once; it is self protection from peer ridicule, it is a show of superior intellect and individuality (more on that in a second) and it is justification for the artificial and repressive manufacturing of context by the corporate owners of media. As for individuality, the ironic and snarky response is the expression of conformity, of a tolerated critical stance that in fact is its exact opposite. Hollywood product, today, as built into it already a sense of snark. Snark-by-the-numbers, a coloring book of snark in a sense. This is because those who manufacture these shows and films are themselves essentially speaking in snark all day long.

Today, Shakespeare is so daunting to perform because language, it’s application (per Wittgenstein) has been so colonized by advertising. Shakespeare’s interior is rendered opaque. Far worse, of course, is someone like Dante. For Dante is even pre-Baroque. The work of revision, the last stage of dream-work, must make the meaning of this unconscious material intelligible. It must remove the conflictual and *incoherent*. When drama today, such as True Detective, since we began with that, strays too far from this manufactured ideal, are experienced as ‘too hard to follow’ (a familiar refrain in twitter responses to the first episode). Game of Thrones, a show that is in fact far harder to ‘follow’, is enthusiastically received. This is not difficult to understand of course, because the familiar must be of a particular sort of familiar. The Pizzolato show is in many ways utterly familiar. It’s a genre narrative and it’s borrowing from Jim Thompson and Woolrich, from Hammet and James Cain, and from Donald Goines. But also Hemmingway, and with a tiny hint of Pynchon. But it is not providing the acceptable context. It is interrupting expectations. Of course, dream revision is in a sense often quite superficial. Hence dream interpretation. The psychic censor tends to eschew subtext.

Diego Velasquez

And the public today is ever less comfortable with sub text, and unless that sub text provides explanation, it is simply too threatening. But there is another aspect to this; and it relates to Wittgenstein again. Wittgenstein wrote both early and late about *background*. That meaning in what we say is only possible ‘against’ a background. This is the context issue, again, but from another direction. Wittgenstein said poetry provided language with its home. A home deeply imbued with the uncanny. But it is also the impossibility of fully understanding this background. Its limitless quality which is perforated by poetics and through which imperfect expression one is able to interrogate meaning, and that interior domain which is so under assault today. The filtering out of background, though, seems the hallmark of contemporary aesthetic processing. It is the mimicking of an autistic removal of distracting background noise. Only mass culture isn’t selectively removing, but sort of clear cutting the background — to the degree that it can. The background to Hollywood product is working toward a highly sanitized context against which the familiar narrative can take place. And again, this is mirrored in political narratives, as well. On a crude basic level this is what spin doctors do all the time, they ‘frame’ the narrative, usually against a backdrop of American exceptionalism.

“[M]any schizophrenics who seem to be profoundly preoccupied with their delusions, and who cannot be swayed from belief in them, nevertheless treat these same beliefs with what seems a certain distance or irony…”

Louis Sass

That is an extraordinary observation. Ironic distance, the better to protect delusion.

There is yet another aspect to the experiential in culture…

“The feeling of the uncanny. How is it manifested? The duration of such a ‘feeling’. What is it like, e.g., for it to be interrupted? Would it be possible, for example, to have it and not have it every other second? Don’t its marks include a characteristic kind of course (beginning and ending), distinguishing it from, e.g., a sense perception?”

Wittgenstein (Remarks on the Philosophy of Psychology)

Edward Hopper

“Approach to a City” 1946

There is in mass cultural product (and I’m thinking of film and TV here, really) the establishment of a familiar atmosphere. Shows resemble other shows, and the music score works a certain way, an identifiable way, on certain networks, and certainly in matters of technology (refer to my post touching on CGI) there are clear cues toward what to expect. But none of this, it occurs to me, is exactly possible unless the viewer anticipates having cues provided (or has been conditioned by watching enough shows of a certain kind to know what to expect). These multiple levels of anticipation are the psychic infrastructure for resisting submission. Atmosphere, however, is probably more created through secondary cues. The uncanny is always (per last posting) a meta-uncanny. But the Wittgenstein quote above is relevant in terms of how a narrative of uncanniness might progress. The uncanny is really only the fleeting experience of something outside the narrative. It is an intrusion. The actual course of the uncanny is then limited, I think, to memory. The uncanny is an exercise in memory, and in one sense, the uncanny is always a failure of memory. It is also an interpretation at its most basic. It has no duration per se. It is an instant. An instant reflected upon, and analysed and even at times re-experienced.

John Chiara, photography.

And it is a memory of several things at once. It is about home, and the sense of loss that every adult associates with home. Even if you live in the same house you grew up in, you have a sense of loss about that home. The idea is linked, too, to how daydreams differ from nightdreams. The uncanny is the insertion of night dream material into daydreams. The day dream is, as Samuel Weber observes, an Aristotelian story on whatever stage presents itself. The nightdream is always the Theatre of Cruelty. But nightdreams are also, I think increasingly, movies. People today have begun to dream cinema. There is a reciprocal aspect to this for cinema also is inducing a dream like state. Freud suggested that the most significant dreams were the ones in which revision had been most extensive. Or as Weber puts it;

“They are dreams that might be said to have been already interpreted once, before being submitted to waking interpretation.”

There is a danger today, I think, even in terms of aesthetics, of thinking in some binary fashion. Us vs them. There is no them, there is only an historical system with a great many tendencies born of Capital, profit, repression, and alienation. There are individual *thems*, certainly, but in art, whoever might be the current curator at whatever museum, will only be replaced by another identical version. The head of whatever studio will be replaced by his or her clone. And if they take the gig, and become CEO or studio head, and they accidently hired the wrong guy, that wrong guy who was originally not a reptile, would quickly become a reptile. Or be fired. Or shot.

Meggy Rustamova

The killing of story has far reaching implications. Our psychic formation is a form of narration. The child sees various taboo subjects that upset previously held beliefs. The child explains it with his own personal myth, as it were. (I do wonder if in certain cultures the audial version of, say, the Oedipal myth might not be in play?). I think there is a confusion of sorts about story and scene, though. All scenes are also stories, just short ones. Even the uncanny is a sort of story. It is worth discussing here the ideas of Ernst Jentsch, in relation to Freud’s on the uncanny. Jentsch saw the uncanny as *intellectual uncertainty*. Jentsch saw the uncanny occuring in people with a higher level of sensitivity to the natural world. The more observant. Freud maintained the connection to the ‘return of the repressed’. Freud also wondered at how context factored into this experience. Samuel Weber noted that Freud’s insistence on the uncanny being connected not to objects or themes, but to their effects, created a sort of theatrical moment. Jentsch believed the primal uncanny was an experience of doubt as to whether an inanimate object might be alive, or a living person might not be a puppet of some sort. Children, of course, attribute animate properties to objects such as trees, or rocks, and of course dolls of all kinds. And almost all children do this. So, the linkage to childhood in the uncanny is very strong, I think.

“The horror which a dead body (especially a human one), a death’s head, skeletons and

similar things cause can also be explained to a great extent by the fact that thoughts of a latent

animate state always lie so close to these things.”

Ernst Jentsch

The loss of story corresponds in an odd way with the loss of mystery in the geographic world. As Kracauer wrote; “…travel { }no longer enables people to savor the sensation of foreign places; one hotel is like the next, and the nature in the background is familiar to readers of illustrated magazines.” This was written in the 1930’s. Kracauer also observed that people increasingly no longer really feel at home anywhere. Travel, tourism today, is merely the fomalized change of location, and a voyeuristic experience that is for many pre-packaged. But the point here is that such experience is imprinted with Capital in the form of fashion. The changes of fashion are periodically rolled out and rarely if ever are based on anything but the need for change itself. People consume change.

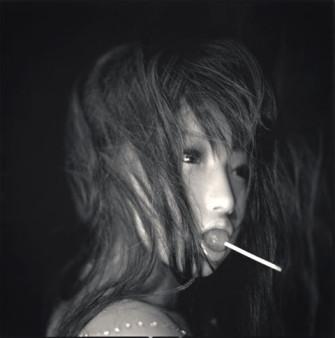

Araki, photography. 1971

“The uncanny is an anxiety signal of the ego against resuscitation of infantile omnipotence of thought and the aggression this entails”

Anneleen Masschelen

The loss of story, coupled to the homogenizing of background and backdrop, and the cinematic colonizing of the unconscious, has resulted in a new form of anxiety. The *it* (Id) is never lacking, said Lacan. But here the loss of story, the erosion of narrative, plays a huge role in this new anxiety. For Lacan it is in fictions that the experience of the uncanny is most acute, because in fictions, in narratives, the experience is less fleeting. The castration anxiety then would a fear of restoring the phallus and fulfilling desire. Undoing castration. And the source of unheimlich is heim. One of the reasons I believe that genre fiction is so compelling is that it bypasses the manufactured interior and lays out a narrative where the primal violence is always somehow stealing away the idea of ‘home’. And since home in the contemporary world is ever less concrete and satisfactory, this loss is liberating and allows the story to operate on the level of permanent exile and homesickness. Of course there is genre and there is genre. The current popularity of sword and sorcery kitsch is more pinned to children’s stories, for example. Science Fiction can be both, but there is an unsettling aspect of validating the instrumental in much sci fi as well as also sourcing children’s literature (though the current Mr. Robot, on USA is a promising outlier). It may be that Kafka is the ultimate uncanny writer. And it may be that Kafka is the influence on even stuff such as True Detective. I sometimes wonder if there won’t emerge (finally) an aesthetic response to many of these factors that transform their effect. That a society of domination, of control, won’t unintentionally create it’s own downfall. That those who control the manufacture of this endless pop culture junk won’t themselves unconsciously construct their own narrative of self annihilation. The problem is that politically, the machine of militarism, that pathological fantasy of the ownership class, is no doubt on auto pilot now. Today, the populace does not ‘see’ that backdrop, the actual material backdrop of carnage and suffering that exists globally. It is outside the story.

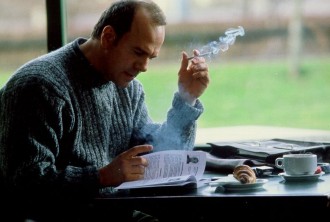

Timeout (L’emploi du temps) 2001. Lucian Cantet, dr.

I want to end with one other observation. In Anneleen Masschelein’s very good book The Unconcept, she lists in her chapter, The Uncanny and Contemporary Culture, a list of artists working today who she associates with the uncanny effect. The list is sadly predictable: David Lynch, Cindy Sherman, Sophie Calle, David Cronenberg, Haruki Murakami, and then W.G. Sebald and Paul Auster. I’d argue that only Sebald is actually uncanny, and that, in fact, the others are exactly the least uncanny of contemporary artists. The uncanny is a link to primordial aspects of psychic development, and it contains plainly political implications, but it is also that which cannot be manufactured. It is resistant to intention, on that level. Cornell Woolrich was genuinely uncanny, so was David Goodis, and a host of noir films from the 1940s. More recently films such Mister John, or Stranger by the Lake, are so deeply disturbing exactly because they manufacture nothing, but in fact operate from an aesthetic strategy of subtraction. Timeout (L’emploi du temps) 2001, directed by Lucian Cantet, is perhaps the very best example. And it is the best example because in few other films is the existence of backdrop both so acute and disturbing, and so fugitive and uncertain.

Mr. Steppling

Thanks for doing these….having done writing and research myself

its hard to write well without investing time and being willing to do

something else many people in encounter today will NOT do…to

reflect…and think.

Thanks again….