Gerhard Richter, “Kafka”.

“But after all, it is perhaps to this inhuman condition, to this inescapable arrangement that we owe our nostalgia for a civilization that attempts to venture elsewhere than into the realm of the measurable”

Jean Genet

“The thinking that aesthetic presentation can open up for us is thus not meant to explain and, by extension, to explain out of existence, what in fact remains irreducible, singular, and resistant within the work. Rather, learning to think aesthetically, to think with and through the work of art, means learning to see what exactly the enigma or riddle is. Thinking means remaining open to what threatens to make thinking impossible.”

Gerhard Richter

There was a debate of sorts this week in social media on solo performance, i.e. one person shows. I have always had a certain aversion to one person shows, although there are many I’ve admired. But I think there is an important distinction that has to be made. Theatre cannot exist without two characters. Two voices. Beckett’s Krapp’s Last Tape is often held up, as it was in this debate, as proof that one character shows are theatre. And it’s a great example because it’s not one character. One actor is used, but there are many voices. In a sense it is an interrogation of one character shows. Now I know of solo performers who adopt many voices during the course of their peformance, and yet, I would still maintain a crucial distinction exists. In Krapp’s Last Tape the other characters are the younger version of Krapp. As such, the actor is carrying on a dialogue with his ghost. When a solo artist changes voices, no such dialogue is really possible. So am I suggesting that residing with dialogue is the essence of theatre? In a sense I think I am. I say *think* I am because I am not entirely certain that such a formula, or any such formula, can really hold up. But for now, I think it is worth thinking about the effect of dialogue as a marker for what I consider theatre. Now even in the best one person shows there is a missing prism through which the autonomy of the play must pass. So, let’s discuss firstly, what is meant by *autonomy*.

Before that discussion, there is another factor. In solo performance there can be no *off stage*. That is a tacit admission by the solo artist. That portal to unconscious or allegorical experience is eliminated. Nobody and nothing is elsewhere. Only the audience exists, and is being spoken to directly, as it were. Within this direct lecture there can be mini-playlets acted out, but the frame for them never changes, because there is, finally, only a single voice. The popularity of one person shows is, besides the fact they are cheap to produce, that the discomfort of the *off stage* is removed. That aperture to the mystery of spoken narrative is removed. A sermon is not theatre. A lecture is not theatre. And solo performance is not theatre, for exactly the same reasons. At this juncture Adorno enters the argument. And to do justice, even in the abbreviated short form of a blog post, I have to delve back a bit to both Tragedy and to Kant.

Nancy Baron, photography.

For Adorno, the aesthetic experience of nature followed upon aesthetic experience and the sublime, not the other way round. For there is a basic terror associated with nature. The domesticated bourgeois experience of *nature* is one associated with Sierra Club brochures, camping trips to National Parks, and picnics. It is not the primal fear of survival against immensity and mystery. And it was Kant who said the sublime was born of a recognition of the power of nature, a power so vast that the principal response was fear. It is only from the vantage point of safety that one can *appreciate* the beauty and grandeur of, say, a volcano or tornado.

“Thus, for the aesthetic power of judgement nature can count as a power, thus as dynamically sublime, only insofar as it it considered an object of fear”.

Kant

It is here that *reason* is introduced as a measure for evaluating the force of nature. Now Adorno sort of altered Kant to the extent that he looked at this tensions in light of the conquest and domination of nature. And he then historicized this experience of wonder at nature as a relatively modern experience. I’m not sure this is quite what he intended, but the point is that the aestheticizing of nature began, systematically, in the 18th century. For Adorno, the music of Beethoven was the perfect exemplar. I believe that Adorno continued to theorize about art in light of his basic aversion to the comfortable vantage point. Nothing in art that produced comfort was worthy of respect.

Gerhard Richter

But back to theatre. The comfortable managed vantage point is always going to be one that, in a sense, pacifies the destabalizing elements. This has nothing to do with message, though. The message, say, of an anti-war play can serve the ideological purposes of its opposite if presented in familiar and comfortable form. Those lounging at the bar after a Lincoln Center show that attacks racism or poverty, are only reinforcing a belief that such things are being dealt with, for, after all, they say, didn’t we just see a play acknowledging this? Democracy is great isn’t it. In the solo or monologist performer the legacy of fear, of the unknown, of the sublime is pacified by not allowing for a dialogue. It is never what happens on stage, it is always about lives off stage. And in addition the monologist is somehow enacting the role of him or herself, and in ways that — to me anyway– cant help but feel branded and cultic.

Cantemir Hausi

But here I think several other things surface. The theatre takes, obviously, all kinds of forms. There is street theatre, and there are dance forms that incorporate narrative. Noh drama is played out in a way that serves as a good example. Or Kathkali. They reside on the intensely ritualized end of the spectrum. One might suggest the monologist is at the other end of the same spectrum. But there is a point at which this idea collapses. And it might just be the nature of most monologists in the West today, meaning Europe and North America mostly. There is strong tendency toward confession and narratives of identity. The other side is sort of agit-prop for various liberal positions and easy to accept bromides asking for racial and sexual tolerance. Rarely does text matter much. The art of writing recedes and performing is foregrounded. There is a weird sort of toxic taste to monologues that I associate with Dinner Theatre quality celebrity impersonations (A Dinner with Abe Lincoln etc). Now performance art per se is, I think, doing something completely different. Or is that true, really? Bob Flanagan is doing something different and there are a dozen others who are exploring the idea of their own body as an installation. But the scripted monologues, Wallace Shawn or Spalding Grey, or Anna Deavere Smith, are ‘acting’ in the sense of characters, and of text spoken aloud. At some point, performance art is destroying the idea of text. Monologists, or whatever one wants to call them, are speaking but they are not reciting a text exactly, and they are erasing the idea of playing anyone but themselves. Creating various masks or voices is just parlour game skill. But then one begins to inch into stand up comedy. What was Lenny Bruce? What is Marina Abramovic? Bruce in retrospect was a kind of Dada political performer who defied conventional category. Abramovic is nothing but a brand. At best it seems to me, most monologists serve as agit prop, politically narrow concerns are railed against, or they are kitsch impersonations, or they are combinations of both of them. The text as something memorized, formally, and then performed in character serves to distance us from the informality of the everyday. Improvisation actually kills the spontaneous, for it is pretending to be natural. The philistine intentions with, for example, Shakespeare, when one hears directors say they want to make the language natural or everyday. They want actors to be erase the poetic unnaturalness of this language. In so doing the ritual space of theatre is mediated by the vulgarity of the normal — except nothing is really normal. So this is the fabrication of a normal. It’s a bit like saying one wants to dehydrate water.

“Bright New Boise”, by Samuel D. Hunter. The Wild Project, 2010.

Peter Uwe Hohendahl says, from his book on Adorno, :“..the turning point in the history of aesthetic theory, the loss of the concept of natural beauty at the moment when the successful bourgeois revolution is completed; while Kant at its beginning still realizes the artificial nature of social arrangements, including those in the sphere of culture.” Adorno built on Kant to a degree that would make Kant unrecognizable to himself, but the point here is that Adorno was redefining and making historical the idea of nature and by extension natural beauty. But Adorno also critiqued Hegel on the subject of beauty. Adorno, Hohendahl points out, saw art and culture as historically and socially mediated and the artist as “a tool for the production of the artwork”. He resisted ideas about genius, and in a sense was a precursor for Derrida in some of this, but the main thrust for this post was that in the early 1800s there began certain trends in how to see culture and art. One was to look for authenticity, much pronounced later, and the other was to realize a kind of freedom in the artwork. All art of importance (and this needs to be talked about) is extralogical. It is not conceptual, and while this is more easily grasped in modernism, it is likely true in other ways for all cultural labor. For Adorno, the sublime (and tragic) is work that emancipates (and kitsch does not) because it releases or allows for mimesis, and this too, though, is dialectical. The sublime and its emancipatory capability is linked to the activation of Nature in the subject. Kitsch, the culture industry, is offering on the whole something very close to simple advertising. They ask for identification; to see one’s position in society, a society of oppression and domination, reflected back to one. This is of course very complicated and Adorno’s most contested idea was probably “truth content”. But I want to try to stick to theatre here. The realistic or naturalistic play is, in 2014, inherently dishonest. Im not sure it wasn’t dishonest when Ibsen wrote it. But I suspect Ibsen was not actually very naturalistic at all. Certainly Strindberg was not, nor Shakespeare, and it is only by the mid 19th century that anything like a formal set of rules for representing *reality* were in play. What distinguishes Strindberg from minor playwrights of his time is that Strindberg was never looking to duplicate anything like an everyday *reality*. Strindberg searched for the transcendent in the everyday, and it was the everyday from which he fled, it was the everyday which tormented him. This year’s MacArthur recipient in playwriting is Samuel D. Hunter. I’ve not seen productions of his plays, but I’ve read them. And even in the photos of the productions it is clear that this is essentially TV. It probably falls into the prestige dramady category. Adorno said “The sublime marks the immediate occupation of the artwork by theology”. Hunter’s Bright New Boise is about theology, or rather ‘faith’, which is discount theology. If in solo performance there is nobody to talk back or to listen, so it is in kitsch where the ritual is erased, the off stage removed, and dialogue goes mute. Even in twenty character plays the dialogue is missing. Another way of saying this is that the naturalistic theatre of representation does not aspire to the sublime because what it is doing, its operation, is as a machine for normality.

Giambattista Tiepolo, “The Martyrdom of St. Bartholomew:” 1722.

The theatre of representation hangs it’s dialogue on a scaffolding that establishes the limits of experience. The break room in a crappy Hobby store (Bright New Boise) cannot become or inform an actual relationship that exists for tens of thousands of minimum wage workers every day. Kafka was a clerk, too. Melville a customs inspector, and Genet a hustler and thief. In each case something of that reality emerges from their work. It would exist in their work even if they wrote about surfers or card sharks. The unnaturalness of all life in Empire goes missing. The construction of reality has always to be questioned; so that the play reaches backward beyond the individual subject’s history. If the stage is treated as the site of mimetic sacrifice, abandon somehow, then it naturally is linked to suffering and memory. Today’s kitsch playwrights, the one’s rewarded for their service to the status quo, are never in touch with suffering. They are at best in touch with complaints. This is bourgeois ideology. Thomas Bernhard wrote a couple of short plays in which only one character spoke, but he put a listener on stage, too.

To follow Adorno just a bit longer, it is important to mention his ideas on truth content, and to do that means discussing his ideas about *enigma*. For Adorno, the enigmatic in any artwork is there not to be understood, or deciphered, but to expand the experience of it, to stimulate that part of us that is linked to, but not identical with memory. Like Calasso, there is always a reminder of the transitory or fleeting qualities of art. As Hohendahl says, with art there is no answer. There must, however, always be questions. In that sense the artwork is to remain a riddle. But there is, as always with Adorno, a contradiction. For the enigmatic must be engaged with, and what he calls the “truth content” is, in one sense, the solution. At the same time that it also can never serve as such. This is why Adorno stressed that there was a convergence of philosophy and art. The meaningless world is illuminated by what remains incomprehensible. In terms of theatre, the example that Jan Kott used in his analysis of King Lear (and which I have referenced several times) is perfect. And it cuts to the essential meaning of theatre. The empty stage with blind Gloucester and Mad Tom, both climbing a non-existent hill, is a truth that can find expression no place else. Its a theatrical truth. There is no capsule explanation for it. The inability to describe factually the experience of illumination means such work makes for a bad commodity.

Bertrand Fleuret, photography.

“Artworks stand in the most extreme tension to their truth content. Although this truth content, conceptless, appears nowhere else than in what is made, it negates the made.”

Adorno

Now it is unsurprising that Adorno has come under attack over the last couple decades. And especially in the U.S. For one of the implications of his aesthetic theory is any work that engenders mass agreement is to be distrusted. This is because of the fatalistic aspect of art. The aesthetic experience of art must point beyond itself, and in that moment there is a tacit failure of the work; there is no agreement in great work, no collective applause for it. The paradox, if that’s what it is, is that by its revealing of something that cannot be articulated outside of itself the artwork opens up possibilities that mere enjoyment close off. In terms of theatre then, it’s only logical that the commercially popular work will be the most suspect. This is perhaps more true now than even fifty years ago. And here there looms a few additional questions.

Marcia Myers

“The context that is invoked to enforce the ideas and practices pertaining to *consensus* is, as we know, ‘economic globalization’.”

Jacques Ranciere

Ranciere has pointed out that psychoanalytic structure of narrative (primarily he means film) has changed since the 1940s. Today the idea of innocence or guilt has been subsumed by a growing global police apparatus. He cites Antigone as, per Lacan, a heroine no longer read as an expression of human rights and liberal piety, but as the harbinger of the secret terror just beneath the surface of the social order. In other words the primal crime that drives narrative is now more intimately fastened to a growing sense of fear that is a sort of collective recognition of how consensus is manufactured; that human beings have become the ‘population’ and that morality is reduced to fact. This is the world of facial recognition technology, which doesn’t work, but which doesn’t matter, and a universe in which everything one does is catalogued. Theatre is economically of little consequence today, in comparison to film. Therefore it exhibits an acute form of condensation. It is very hard to subtract the false, the untruth, in theatre, and far easier to allow it some life in film. The medium of film is more forgiving of lack of unity than theatre. For film is more than closely linked to media and corporate control of information. So if we take this back to ideas about solo performance, and why I feel distinctions are crucial in describing this form, it is because the originary space of theatre is one in which someone must be listening, in person, on that stage. Without that, the narrator too easily is manufacturing consensus. The ‘broken promise’ to which Adorno and Horkheimer both alluded, is also inseparable from the unrepresentable, in the sense that a future community was always there in art’s appeal; and that today the conquest and co-option of all life, the extent of social domination, has meant that the mystifying nature of what is called post modernism is really just the acceptance of that promise being broken, it is further, a new rewards system for those who embrace the lies.

Noh stage, Miyagi Japan.

“Art is at once both autonomous and a ‘fait social’. As he (Adorno) puts it, the artwork’s autonomy consists of resembling – but not imitating – the society of empirical reality.”

Then he quotes Adorno (a well known quote): “It is by virtue of this relation to the empirical that artworks recuperate, neutralized, what once was literally and directly experienced in life and what was expulsed by spirit.”

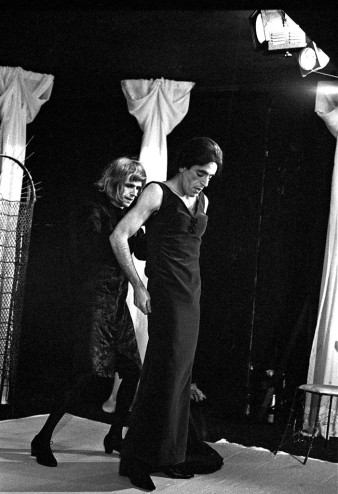

The Maids, By Jean Genet. (Living Theatre, 1965) photo by Mark Anstendig.

Adorno believed that primal mimesis, if we want to call it that, achieved significance, in its expression, by discarding what it deemed as false or untrue. For the purposes here, I will just try to lay out the reductive simple version; the value of art is in a spiritual awakening, but that awakening or revelation or whatever one chooses to call it, only happens through a process of internal integrity. A process of vetting mimetic material for signs of falseness. The practical meaning of this for artists is one must learn to get rid of cliche and sentimentality and magic thinking and junk science and most of all the narrative expressions, or images that co-conspire with the repressive actions of totalitarian societies, and to fight off commodification, since it participates in all of the above. Great artists don’t have to be philosophers, they simply must learn to sift down through the jumble and chatter and fraudulence of daily life, to hear something integral and honest. Adorno said all art is in movement against society. That unless it is, it is junk. Kitsch. Propaganda. And narcissism.

Jonas Burgurt

As Tom Huhn writes; “It is specifically the entirety of external reality’s spell that the artwork mimetically opposes – this logic is directed in particular against the spell of that reality rather than its material constituents.” That spell, for Adorno, had to be opposed. Opposed but recuperated later. It is what left Adorno, in his dialectic, to still see art as an enlightening force. The artwork mimetically produces itself by producing its requirement. This happens on levels that are buried, usually, anyway. So, when I have said all stories are crime stories, all stories are travel stories, and all stories are about homesickness…this is because all art reaches backward in the exact degree to which they project or imagine another, different future.

There are myriad forms of the sensible. The contours of tension in mimesis, from its originary impulse, to it’s later grasp for self-identity, make all of this almost infinitely complex. The discourse on culture in the United States, and largely throughout Europe, too, but most obviously in the seat of Empire, is one in which only the most shallow, most familiar, and most domesticated is allowed survival. The gentrification of consciousness, an already colonized consciousness. The single most common response today, I find, whenever anything of a serious nature comes up in discussion, is the response that minimizes, the voice that tries to suggest this is all too familiar. It is the desire to pretend the unfamiliar IS familiar. That the disruptive happened before, nothing came of it. It’s all so ten minutes ago.

Anthony Goicolea, photography.

I wonder often at why it is not more obvious that the solo performance, the one person *play* is not experienced as a deficit. That the missing texture of the symbolic listener is not felt more. My suspicion is that the society at large has forgotten the role of the listener. Partly because of electronic recording, and more significantly electronic surveillance, the individual’s relationship to his or her own voice has changed. People certainly speak less to their neighbor, they know fewer words, and they are less interested in hearing the world around them. But then that world around them is falling silent. For all the talk of noise pollution, the natural world is falling mute, and when it’s not, people increasingly plug their ears, literally, to listen instead to their iPad. The phenomenon of blocking out the sound of the world around you is one rarely talked about, but the implications for theatre’s future are profound. The music of language found in the medieval Italian of Dante, or the English of Donne and Milton and Shakespeare, or the French of Flaubert and Rimbaud, the German of Goethe, the Spanish of Cervantes — that kind of density is gone, likely forever. People don’t hear what is said around them, they re-narrate based on guesswork, previous communications, and all of it based on film and TV. The natural world, the sound of rain and oceans and tides moving in, the distinction between summer winds and autumn, or the specific bird song (when there are any birds singing) is lost.

Bernard Faucon, photography and mixed media.

Anna Deavere Smith, “Let Me Down Easy” 2009.

I want to mention Gerhard Richter here, for Richter is one of those rare painters who can articulate what he’s doing. He is also a cogent cultural critic. Richter pointed out that in Adorno’s pessimism there is a promise of redemption, but that Adorno pulls the rug out from beneath you at the last second. Adorno’s promise of redemption, as Hohendahl says, is based on recognizing that redemption is impossible. This is that final sacrificial stage of the dialectic for Adorno. The artwork dies as it points toward redemption. As Jameson said of Adorno’s idea of ‘truth content’: “…it seems at least minimally possible that it cannot be philosophically described, since it is inscribed in a situation of well nigh nominalistic multiplicity in which only individual works of art, but not art itself, have their various truth contents…”. This is correct in a sense, but then ‘art itself’ is only a shadow stand in for all culture. Great works….per Adorno: “The understanding of works of art, therefore, besides their exegesis through interpretation and critique, must also be pursued from the standpoint of redemption, which very precisely searches out the truth of false consciousness in aesthetic appearance. Great works in that sense cannot lie.”

The Homecoming, by Harold Pinter (Peter Hall production 1965 with Vivian Merchant and Ian Holm)

http://www.cna.org.cy/photoinfo.asp?id=1a78b5df758f4cdd84d1f13a7d083495

Now, never mind that Nobel Prize winner Harold Pinter was on the same committee to defend Milosevic (as was I, and Ramsey Clark and many others), nor that the U.S. state department propaganda on the Balkans has been factually refuted for more than a decade. It doesn’t matter, for what matters is a narrative that allows the public to indulge in a faux outrage about a history they clearly know nothing about. Handke’s integrity deserves special commendation, and respect. The rewriting of the Balkans has taken place by institutions funded by the U.S., and NGO’s dependent on U.S. business financing. Essentially they are asking you to believe NATO. The current declarations on Srebrenica are created in isolation, framed as scientific, and promoted by corporate journalism and by NATO and NATO friendly NGOs. And gradually they come to serve as the official history. The long shadow of U.S. propaganda infects everything. It is a simulacra of history, a phantom marketing device and increasingly inimical to the truth, to material history. In the end it is more validation for Capitalism and Empire. Allowing small truths to exist the better to squash greater more important truths. It is the new Brave New World.

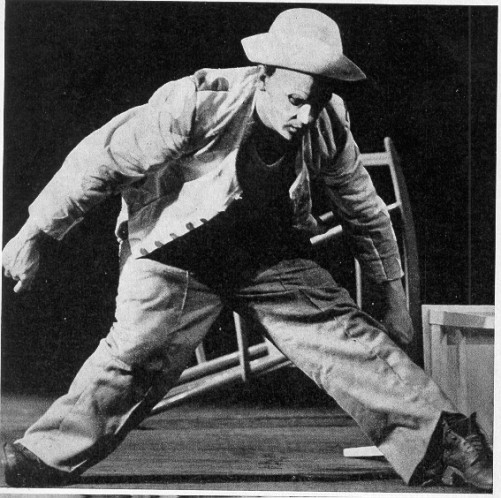

Original production of “Kaspar”, by Peter Handke. With Klaus Peymann.

another issue about text — maybe related to the lost art of listening — is that it seems directors and actors don’t trust text anymore. go see some Pinter, Beckett, early Mamet or Shakespeare today and it feels as if the production is embarrassed about the text and has to work around it — almost overcome it. directors and actors seem much more comfortable with stage business, blocking, vocal dynamic, overt emotion to help keep the audience on the moving sidewalk and usher them to the end of the performance without anyone becoming bored or confused. there is never time for “sinking into” the text, only glossing it by moving the audience quickly to that stage business where we always get a laugh…or to this line where we reveal the knife… i’m not sure how comfortable audiences are with text since i’m not sure there is much opportunity to experience it, other than reading plays alone at home almost like one would read poetry.

(Taken from Harold Pinter’s Nobel Prize speech) Brief note on Pinter’s aesthetic creation process:

When writing a play, he says that, most often, what comes first is the word (line), then image, and only finally meaning.

It seems to me that that represents the three levels of mimesis in a drama: the word emerges first, meaning comes last. Meaning does not determine the “texture” of the play — it is the other way around. And before even the word is the primordial, undetermined, ineffable background of the play. It is the psychic material from which everything else emerges.

The problem starts when word > image > meaning is not allowed to emerge from the background material, but when the order is reversed, so that meaning is predetermined, followed by a narrow set of images serving the meaning, and only finally allowing words as mere surface decoration. The result is that the psychic background material is stunted and truncated. The extreme truncation results in Hollywood kitsch.

Oops, I posted that too fast: just wanted to clarify that only the first two paragraphs of my previous comment was taken directly from Pinter’s speech; the rest is my interpretation, expansion, and exegesis of what he might imply.

@george: Yes absolutely. I have had much the same experience when directing plays in the US. Asking actors to just say lines goes against the idea of *selling* their performance. They often do not hear what they are saying. And getting actors to listen on stage is very hard, because they indicate they are listening rather than listening.

@Exiir………..when i heard Pinter’s speech, which is brilliant beyond description, I felt also very vindicated for what I had been saying for years. And its a testament to how theatre and writing is taught in the US today that when i had said very similar things I was attacked not by students but by professors. And i would be today as well. And yes you are quite right that this is directly connected to mimesis, and that seems something totally alien today in the culture. The word never even comes up.

“And before even the word is the primordial, undetermined, ineffable background of the play…” thats a terrific description. That is the place one has to get to, or approach, in order to hear real voices at all. You have to listen very hard I think today, to get there.

Regarding words & acting — I almost think that, nowadays, the most revolutionary thing to do with directing actors with regards to text, is to assume that the text means exactly what it means, no subtext, no nothing. Not quite, but almost. Forget the conventional wisdom that actors should act the undercurrent impulses, internal monologues, and emotions of a coherent “character” to impersonate, and that the words should only be the unimportant floating bits of ice on top of the “current” of physical & gestural acting. There’s an appropriate time and environment for everything, but the time, where that was once a very important corrective, is now passed. Nowadays that philosophy will only bring overacting and indifference to text. So the opposite corrective is needed — the text has all the meaning and the exact meaning only, no meaning is extra to the text (for an actor at least).

A good analogy would be — recite your lines as if you were a poet and they were your poems. You wouldn’t impersonate, emote, or gesture unnecessarily, would you? You’d try to make the meaning of your words as clear as possible, rather than wanting the “way” you say the words be the focus.

Coltrane once said, after he recorded his album of standards, and asked why he had done that kind of album,…..”The hardest thing to do is play a melody correctly start to finish”. (Im probably paraphrasing slightly).

Applying this to music….It’s interesting how solo performances are associated with being more immediate, intimate, or legitimate. For Dylan, the outrage wasn’t just over acoustic vs. electric. It was that he was no longer solo; a band was backing him and detracting from The Troubadour and his message (or, so, some felt). One also sees band leaders touring solo (Jeff Tweedy of Wilco, for example) performing their songs acoustically without backup. But things can be deconstructed too much and seem threadbare; there is no more sonic mystery remaining….Something is inherently exciting about witnessing the interplay among a group of musicians. Each performance can be different from gig to gig. Human interaction on-stage is as vital as between performer and audience. Solo can be narcissistic & banal while the opposite riveting and engaging. Good art engages.

Last, touching on what Exir wrote, much can be discussed over the mystery of how songs are written and the interplay between melody and verse (which one comes first?). A song’s meaning (if it has one) can be interpreted in vastly different ways.

oh man, this can get so complicated. Music being the most mysterious of art forms. But see, Id argue (maybe!) that a capella….well, single a cappela….is the monologue. And group a capella is already different. I once argued that Aeschylus was on inhalation and Sophocles an inhalation and an exhalation….and that Euripides as already breathing. And thats probably a real discussion, for Aeschylus is right on the edge of not being theatre, and perhaps is the tragic without conventional theatrics. Im just sort of free associating here…..but i think its interesting. Adorno wrote about music more than any other thing and at some point I have to dig more into that. But just as a final thought here…I mean if we took say Bach, or Shoenberg or Coltrane or Ornette….and then , I dont know, Hank Williams; Id have a hard time discussing those comparisons. I never have and its because for whatever reason Im stuck dumb with some kind of confusion about music.

Whenever you dig more into Adorno’s writing on music, would be interested in your take on his famous critique of jazz.

Yeah, that was just his having no grasp of what was meant by jazz. He was thinking of stuff that we wouldnt call jazz. Its not an excuse, but its one of those glitches, and there isnt much to say about it honestly. I think he had in mind muzak level pop music of the time. I honestly dont think he ever heard jazz or bothered with trying to hear it.

Complicated indeed! After commenting I questioned what I wrote. Which do I like more: Beethoven’s sonatas or symphonies, etc. I also began thinking about if one type of art-form is more “demanding/participatory” than another. For instance, music can be just so much background noise if one doesn’t want to engage with it. Movies or theater? Much more participatory since one is in front of something occurring. Still, I’ve fallen asleep at movies/plays. Painting? Extremely participatory. One has to decide to look at it first. I remember staring-long at a Jasper Johns at the Art Institute just contemplating the repetition or break there-of. Last, you mention Coltrane. Listen to the song “Giant Steps”. It begins almost a cappella with Coltrane blasting out right from the gate (accompanied by some hat-work) and then slowly the band comes in until they’re all playing the “head” which closes the song (totally reverse of a “normal” jazz progression). Genius!

Well Adorno’s attitudes toward jazz might also have just been a knee-jerk rejection of the ‘new’, which tends to happen if you’re born into one generation too soon. I’m not excusing it but just pointing it out as a blind spot. It’s in the same class as Gore Vidal’s outright rejection of film as an art form.

Exir,

In response to your comment on acting:

“Regarding words & acting — I almost think that, nowadays, the most revolutionary thing to do with directing actors with regards to text, is to assume that the text means exactly what it means, no subtext, no nothing. Not quite, but almost. Forget the conventional wisdom that actors should act the undercurrent impulses, internal monologues, and emotions of a coherent “character” to impersonate, and that the words should only be the unimportant floating bits of ice on top of the “current” of physical & gestural acting. There’s an appropriate time and environment for everything, but the time, where that was once a very important corrective, is now passed. Nowadays that philosophy will only bring overacting and indifference to text. So the opposite corrective is needed — the text has all the meaning and the exact meaning only, no meaning is extra to the text (for an actor at least).”

There is a lot to what you say here and I got me thinking. To add onto your comment, in support of the kind of acting you are encouraging (as I take it, an acting rooted in direct listening to internal/external impulses/images, physicalization, risk taking, and attention to subtext)–I suggest that if it is a strong text, it can handle what the actor does with it. A great piece of text can reveal all sorts of excess meaning and layers in the body of an actor who is honestly physicalizing that text. It takes a lot of vulnerability to do this, and it is hard to be vulnerable… It is a complex vulnerability to the body, to memory, to the environment, to the Other that is watching, and of course, to the text itself. And opening up to those things is all a sort of “listening” that John was mentioning. I suppose this process of opening up/listening that the actor must do is similar to what the playwright must do before finding what you referred to as “the primordial word.”

A playwright cognizant of the form of theatre, will somehow implicitly know that what they are writing is incomplete on the page–or at least, they will have a feeling that the “unknowns” they have begun to unearth in the writing of the text can only be further explored through the live actor AND the audience.

There is a risk in producing any great play–look at some of the modern productions of Shakespeare that are so deadly to watch. There is, I think, a false assumption that great texts are precious and that we must be reverent to them. But what does “reverence” look like?–True reverence and respect is not something that can simply be taught, but must be practiced and reshaped every moment. Great texts are not so precious as they are powerful; and, these texts feed off the morbid, the passionate, the grotesque unconscious of humans–great texts begin to starve and whither when translated onstage in a calculated, cerebral, and formulaic way. There is safety and control in a reliable formula. We don’t like feeling out of control, but we ARE out of control (at least the mass cultures of the West). I think the theatre could be such a powerful tool, in part, because it contains that possibility of living in uncertainty.

Calla:

Agreed. The issue here I think is historicization, and the argument that any great artistic and/or intellectual figure from the past “needs to be appreciated and understood in context”. There’s the short-sighted belief that someone like Shakespeare has been digested by scholars before us, so therefore our ‘homework’ has been done already. Naturally, you can’t argue that Shakespeare’s significance is merely a “historical” one when his work is still clearly relevant to contemporary existence, so it’s a position of avoidance under the presumption his work has already been properly engaged with. Well not everything to be unearthed regarding Shakespeare has already been unearthed, even if some people would like to think otherwise. There’s a reason his importance is actively reinforced ‘ad nauseam’. The belief is these figures should merely be cataloged and checked off as historical sign posts and that by this point the only purpose served by reading his work is one of ‘historical understanding’. The counter point of course, directed at me, was that if his importance is ostensibly more than a ‘historical’ one, it’s because he’s merely being appropriated to advance an ideology, which I would argue is nonsense, and I think this goes back to the ‘primordial’ and the emancipatory effect a work of art has on each new person who engages with it for the first time regardless of how it’s been digested by others before them.

Calla:

Agreed. The issue here I think is historicization, and the argument that any great artistic and/or intellectual figure from the past “needs to be appreciated and understood in context”. I discussed this very issue on another forum a few days ago, although not precisely with respect to Shakespeare. There’s the short-sighted belief that someone like Shakespeare has been digested by scholars before us, so therefore our ‘homework’ has been done already. Naturally, you can’t argue that Shakespeare’s significance is merely a “historical” one when his work is still clearly relevant to contemporary existence, so it’s a position of avoidance under the presumption his work has already been properly engaged with. Well not everything to be unearthed regarding Shakespeare has already been unearthed, even if some people would like to think otherwise. There’s a reason his importance is actively reinforced ‘ad nauseam’. The belief is these figures should merely be cataloged and checked off as historical sign posts and that by this point the only purpose served by reading his work is one of ‘historical understanding’. The counter point of course, directed at me, was that if his importance is ostensibly more than a ‘historical’ one, it’s because he’s merely being appropriated to advance an ideology, which I would argue is nonsense, and I think this goes back to the ‘primordial’ and the emancipatory effect a work of art has on each new person who engages with it for the first time regardless of how it’s been digested by others before them.

Oh, I apologize about the double post. The computer was acting up on me.

I wanted to make one observation about directing Shakespeare. I did a tri lingual version of Lear when I was in poland. Ive mentioned this before. In english, polish, and Norwegian./ And there were two Lears on stage all the time. So obviously this was an experimental Shakespeare but it never felt like that. At the time I thought, well, you couldnt do this with Kyd, or even with Marlowe. And yet, probably most serious theatre goers know Marlowe almost as well. So its not completely familiarity that allows one to radically re work shakespeare. One does not see other work, or other writers characters in life as if they resembled Lady macbeth, or Iago. One doesnt think or hear; ah, thats a Tamburlaine sort of moment. Shakespeare is unique I think in that he has so deeply seeped into western consciousness. The King James Bible, as well. Our language was invented by shakespeare to some degree, and how we think about thinking about ourselves. All of that happened during that period. The west had left antiquity behind to some degree. One can experiment with Ibsen say, or Chekov, but its not the same. There isnt the same relationship to the text. In Shakespeare there is a textual authority, it cant be erased regardless of how badly you perform him. I once saw a jr high school version of Henry VIII……..and it was terrific. It revealed something new in the play. And it remains one of my favorite versions of shakespeare, that Ive seen. And i say this without any irony. None. Partly, interestingly, it was these kids were so focused on remembering their lines that they just came out on stage and said them. Almost closing their eyes to remember them. And I think I understood something then about modern theatre and text.

There is also something to be said for putting actors in generic masks. Much harder for actors to “present” their performance like they are used to. Also focuses actors/audience on the text and the sheer physicality of human bodies on a stage.