Fernando Calhau

“Psyche is extended,(but) knows nothing about it.”

Sigmund Freud

“Walking is in fact determined by semantic tropisms; it is attracted and repelled by nominations whose meaning is not clear, whereas the city, for its part, is transformed for many people into a ‘desert’ in which the meaningless, indeed the terrifying, no longer takes the form of shadows but becomes, as in Genet’s plays, an implacable light that produces this urban text without obscurities, which is created by a technocratic power everywhere and which puts the city dweller under control…under the control of what? No one knows.”

Michel de Certeau

“We know that under the image revealed there is another which is truer to reality and under this image still another and yet again still another under this last one, right down to the true image of reality, absolute, mysterious, which no one will ever see or perhaps right down to the decomposition of any image, of any reality.”

Michelangelo Antonioni

from Encountering Directors

by Charles Thomas Samuels

In film, unlike theatre, the sense of ‘place’ is created out of various elements. It is this composite. The very best film often works to convince us of place, before all else. Let me digress a bit first…

There is a marked trend in Hollywood product, both in TV and cinema, that intensifies the scapegoating and demonizing of the underclass, and of immigrants, and the continued manufacture of specific racial and nationalist villains (lately that means Russians and all Arabs and muslims, as well as Chinese) to be vanquished. It is too tedious to really survey recent TV, but a couple examples. The Last Ship, a post apocalyptic sci fi series, about a U.S. Navy destroyer cruising the world looking for a cure to the virus that has killed most of mankind. In episode two, we already have Guantanamo Bay and Arab terrorists (even in a recently ravaged planet where 90% of the population has died within a month, there is still space for Arab terrorists) shooting at our heroes and a Russian ship bearing down on them. There is no sense of space, of horizon, of salt air or ocean currents. There is only the uniform, the servile attention to authority, the shiny metal of the weaponry. The inflexibility of these designations and character cliches speaks to just how firmly entrenched is this material. In the odious Tyrant, produced and developed by Israeli Gideon Raff, the theme seems to be, judging from two episodes, that evil is the only real inheritance of and for Arabs. Arabs just have shitty DNA. The liberal gloss (the would-be tyrant’s son is gay) only serves to reinforce the Imperialist agenda of the show. This is Obama style Imperialism. Its cool to be gay, but not Arab. Well, its even sort of OK to be Arab if you are the sort of Arab who desperately wants to be white and western. Gentrified fascism. But this is the defining element in kitsch Hollywood product, now. And again, no sense of place. But more on that below. There is another sub-text in a lot of narratives from the culture industry, and that is a resurgent Christian symbolism. From Dominion, to Leftovers, to Believe, to Resurrection, the backdrop is corn ball Christianity. The backdrop, increasingly, to science fiction is a Christian symbolism, and Old Testament names. That science fiction should trend toward a reactionary Christian cant really be a surprise (notwithstanding many faux left apologists for Science Fiction). What IS surprising is the extent of this new fascination with Rapture, and Angels, kitsch Devils, exorcism, etc, etc. in current TV and film. In a sense, this is the legacy, to a degree, of the Da Vinci Code, and before that, perhaps, to The Exorcist. It is also just the bankruptcy of imagination, the recycling of tried and true (familiar) symbols and ideas. Most of the writers for this junk, are not Christian zealots, but just poorly educated hacks. Now, that there might be, and probably is, a unified Christian producing entity. The ‘Christian right’ made that choice, to get into films and TV. The result is this growing discourse that traffics in these cliched theological ideas.

In Hollywood TV and film the idea of blue collar worker is blurring with that of criminal. The proletariat, the lumpen proletariat anyway, is almost synonymous with criminal. Notwithstanding the sentimentalizing of the “working class”. For that is also a trend. The noble savage as day labourer. One sees this condescension a lot in Hollywood, in fact. Actors as diverse as Nick Cage, Ryan Gosling, George Clooney, Brad Pitt, Matt Dillon, Ben Affleck, and the list goes on; have all played lumpen under class characters, as sexy hyper masculine and most of all, *authentic*. The style codes are exaggerated, the accents exaggerated, and driving these mannerist affectations is a both envy and hostility.

Ryan Gosling, Place Beyond the Pines, 2013.

Brad Pitt, Killing Them Softly, 2013.

“Narratives defining self become legible to others only in the concept of larger narratives of group identity.”

Steven Flusty

The first episodes of Tyrant take place in a fictional middle eastern country. The signifiers are there; sand, palm trees, heat, and a palace. There is sexual deviance, sadism, and psychosis. There is a sterotyped military leader, and so on. But there is no sense of place. No real location. There is no feeling of sand, no feeling of heat, no sense of the smells of sandlwood, musk, or bahkoor, or the vast quiet of desert nights. There is no sound of morning prayers or feel of the giant sun that begins to heat the landscape. The visiting Americans seem not to get suntans, not need hydration. Instead we get kitsch melodrama, racist and patronizing. The feeling is of being in an office in Century City or Beverly Hills. The show is filmed as it were a detergent commercial. I suspect that some of the neo colonial ideological backdrop of its creator has seeped into the sense of stasis and pseudo formality in the staging of scenes.

Raphael, Sistine Madonna (detail).

There is no real place in any of these shows. It is interesting to watch, as I did recently, Antonioni’s Blow Up. I was reminded of it because of a Belgian crime film I had seen the day before. Der Berhandling, a Belgian child kidnapping procedural that isn’t really very good, though its of side bar interest that Belgium seems fascinated with their own real crime stories of false imprisonment, torture, and paedophilia. But in this film there are train tracks and deep bushes and shrubs where the killer flees. And its a film with superior cinematography. And I thought immediately, Blow Up. So indelible is that London park, and the search for what isn’t there, or perhaps *is* there. There is a distrust of Antonioni in general, and of Blow Up in particular these days. As an example, it is described (by Asborn Gronstad, in a recent Film Comment) as “In retrospect it is not difficult to read Thomas’s and Blow-Up’s key narrative premise as epitomizing the 1960s art-film conventions of the cinema of ambiguity. What above all defined this “festival film” (of which Antonioni himself was a principal exponent, along with directors like Bergman, Fellini, and Godard) was a peculiar synthesis of the modes of objective realism, expressive subjectivism, and authorial commentary. A sense of indestructible uncertainty thus became the raison d’etre of films like Blow-Up. Much as we may still be able to admire Antonioni’s accomplishment, however, his purposeful orchestration of the ambiguous now seems, if not dated, if not too studied, then at least somewhat routine (as does the plethora of psychoanalytical readings-centering on Thomas’s voyeurism and misogyny-that the film has invited over the years).”

Blow Up, 1966. Michelangelo Antonioni, dr.

” The denial of objective truth by recourse to the subject implies the negation of the latter: no measure remains for the measure of all things, lapsing into contingency, he becomes untruth. But this points back to the real life-process of society. The principle of human domination, in becoming absolute, has turned its point against man as the absolute object, and psychology has collaborated in sharpening that point. The self, its guiding idea and its a priori object, has always, under its scrutiny, been rendered at the same time non-existent.”

Adorno

Astrid Kruse Jensen, photography.

Under a system of domination, self help psychology (the adaptation to the status quo) is now a reinforcing of privilege and stigmatizing of the other. That is largely the message of shows like Tyrant. The acceleration of the trashing of Freud runs alongside the valorizing of the self. This is the secret impetus of pop psychology; an acceptance of alienation, and a cataloguing of its symptoms, and as a member of the status quo, the bourgeois white “majority”. The embrace of diagnostic categories helps define the individual as a non individual, but a recognizable one. A sort of faux individual. The titillation of these shows, the sex and violence, are there to be mildly condemned, but also mildly accepted, and even approved. One’s symptoms are one’s identity. In Antonioni, the narrative unravels leaving only the bottom layer of illusion, and hence of terror. And along the way, with these spatial models that equate the body as a core naked truth, the reality of there no being no core, or only a core of other different layers, is erased. And with that erasure comes the loss of dialectical thought. The Freudian spatial model always implied impossible complexity at the center of things, complex and perhaps unknowable.

Adorno pointed out that only those with nothing to sell, outside the sphere of exchange, can create refuge when refuge no longer exists. The self is under constant surveillance, and it is only in the figure of the stigmatized that some notion of freedom exists. This accounts for the envy of the poor, the desperation for Hollywood and its celebrities to participate in the ‘authentic’. And also accounts in part for the symbolic punishment (never mind the actual real) of the poor and marginalized. And again, anyone with a day job is represented as borderline undesirable, and a threat. The various outsiders, sexual, political, biological, are rewarded when they ‘come inside’, adapt, round off the corners of difference. The narrative is full of ‘neurotypical’, or ‘differently able’d’, but in reality it is those willing to submit to a homogeneous ideal that are accepted for their “difference”. Those who dont are ruthlessly stigmatized and shamed.

Anselm Kiefer, photography.

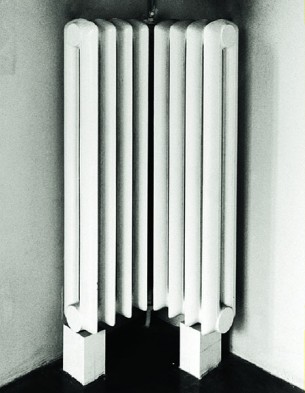

This is the paradox, or one of the paradoxes of mass culture today. And here is it worth noting the contradictions of post modern surface, again because it is the delivery vehicle for the ideology of a disposable underclass. Van Doesberg, in the 1920s, wrote “Man does not live within the construction, within the architectural skeleton, but only touches architecture essentially through its ultimate surface.” It is interesting how this primacy of surface was injected with a functionalist ideology at that time. I am reminded here how Le Corbusier, and tellingly, Wittgenstein (in the one house he designed, for his sister) were idealist ventures, and criticized for it. Wittgenstein’s sister said she could not live in this house her brother designed, for it was a house where only Gods could reside.

Today, the elevated aesthetic of an Antonioni is dismissed as dated. As self consciously obscure. The culture industry, and, more, the elite establishment, promote these ideas of revealing something by presenting another layer, which is one that is always reductive but attractive. The surface becomes the excavated core *naked* truth, in which certain decoration has been removed. The removal of the human is done by sleight of hand. The generic core of new age pop psychology is wrapped up in maudlin chintz of sentimentality or dehumanized ‘human-ness’. It pretends to celebrate human individuality, but reduces that individuality to a chimera.

Giorgio de Chirico

It worth exploring these ideas a bit more. The absence of the human is not the same as an image without people. The marks left by the human display more, often, than bodies being present. De Chirico’s empty plazas and squares express a tension because of what has been either expelled or lost. Shadows, the monuments, the stark eerie light, all suggest portents and prefigure a quarantine, or curfew, or just abandonment. This idea of depth, a revisionist depth if you will, in which as layers are torn away, the closer one gets to the core, to the truth, also entails the idea that with each layer that is removed things become less complex. Until, finally, at the core, where things are no longer clothed, where we are naked, there is simplicity, there is the reductive and compulsively repeated banality of solipsistic cliches. This is the ideological imprint of this revisionist model of depth. Excavate away the complexity. What is happening in this model of depth is the argument of the fascist. Crude, one dimensional mystification being presented as hard fought truth. And this reduced simplified new age cliche is presented as a metaphysical liberation.

When I taught at the Polish National Film School, the screening of Antonioni was met with indifference, or even hostility. And now as I think on it, only he and Pasolini were quite so disliked. Even Bresson has God, after all. Antonioni does not. When L’Avventura was screened at Cannes it was famously booed. But it soon became clear that this was a seminal film. To my mind Antonioni made three giant films; Red Desert, The Passenger, and L’Avventura. In each, the sense of forgetting is primary. People are forgotten. Antonioni, like Pasolini, was anti sentimental. In his world, the existential search goes on, even as belief in the search dissipates. But there is also the confrontation between the miseries of daily life, and a kind of transcendent beauty and sexuality. Wittgenstein’s house was made as a residence for Gods, so Antonioni made films in which a certain ideal vision and beauty is in constant conversation with suffering. They are films made to be watched by Gods.

L’Avventura, 1960. Michelangelo Antonioni dr.

“It also showed—

and this was harder for audiences to grasp—that events in films do not have to be, in an obvious way, meaningful. L’Avventura presents its characters behaving according to motivations unclear to themselves as much as to

the audience.”

Geoffrey Noel-Smith

On L’Avventura

The Passenger, 1975, Michelangelo Antonioni dr.

Antonioni’s films, or at least the work that began with L’Avventura, are about the camera, about what and how the camera captures. They have always felt to me close to still photography. Its probably no accident that photographs are prominent props for both Blow Up and The Passenger. My point here is not to do an overview of Antonioni, but only to suggest his relative unpopularity should come as no surprise. The Passenger (still probably my favorite Antonioni, and that I accept is perverse) is, first, a remarkable looking film, but it is also a perfect sort of parable for the paralysis of identity. And perhaps that has been Antonioni’s subject all along. The final long take remains one of the most perfect and beautiful and haunting shots in all of cinema. Modern identity had petrified even further between 1960 and 1975. Antonioni was preternaturally sensitive to the times in which he made his films, and the anomie of his mostly bourgeois characters is set against landscapes of dialectical knottiness. Class is never really absent. But Antonioni was not an overtly political director, nor one interested in messages or themes. He was a scientist of the sublime. His characters were not searching for revelation, but Antonioni was.

“Antonioni’s sense of locale is impeccable: the empty town in ‘L’Avventura’, sixties London and the magical park in ‘Blow-Up’, the highways and byways of Europe in ‘The Passenger’. As a child in Ferrara, Antonioni was fascinated by buildings. He would make models and place people inside them, making up stories as to why they were there. This interest in space, and the relationship between people and space, runs through all his work. ‘The Passenger’ is almost exclusively about people moving in, through or between buildings.”

Richard Skinner

Richard Pousette-Dart

There is that white light through the wrought iron window bars, in the penultimate shot in The Passenger, It reminds me a good deal (in terms of the framing here) of a shot in Out of The Past, the Jacques Tourneur noir fromn the 40s. In that film it was Mexico outside, in that white light. In the Antonioni it is Spain. It is the same light, it is Genet’s light, it is Juan Rulfo’s, transfiguring and absolute. And these details, sensory and metaphorical at the same time, are what is gone when you watch The Last Ship or Tyrant. Or the new HBO series The Leftovers (directed by the always turgid Peter Berg), which is more cheap Christian wet dreams about the Rapture. This is an expensive show, well photographed I have to say, but still lacking in that sensitivity to place. The entire project, from performances to photography to writing feels shallow and arid somehow. The best directors have an elusive mise en scene, a difficult to pin down quality, found in each frame, that gives them that ineffable quality of depth. The Leftovers feels familiar and unrealistic at the same time.

Pop culture, the VICE writers, those at all the Murdoch run sites and papers, and Murdoch imitators, have become the sort of intellectual tempworker gatekeepers to defining what is hip and successful. None of these writers are in any way writing criticism. They are reviewing. With a lot of ‘tude. The Google search engine seems to be favoring a lot more of this junk lately, but that might just be my perception of things. Some new pop culture is better than others, AMC’s Halt and Catch Fire is the origin story of Microsoft, and its beautifully photographed (with the suburban nights looking a lot like Rut Blees Luxemburg) and the writing is surprisingly indirect and elliptical. I doubt it will get good “reviews”. The prestige cable product today is less and less about writing and narrative. It is more and more about concept. The overall concept of a project which means, really, is it marketable? But beyond that, Halt and Catch Fire is undoubtedly too oblique. It doesn’t pander to the intended 20%, educated and white, audience. Its criticizing them, in fact. Subtle criticism, to be sure… but the success of a show like Breaking Bad was due to knowing how to flatter the audience. In a sense the network and cable prestige shows today are all origin stories; but the origin in question is the audience. This ever less educated, or ever more badly educated, twenty perecent want their entertainments to function a bit like Tarot readings, or astrology charts. This is who you are and this is where you came from and why. Breaking Bad did that, Mad Men did that. The half decade earlier incarnations were more about a kind of revisionism of movie history. The Sopranos was, finally, about the history of gangster movies.

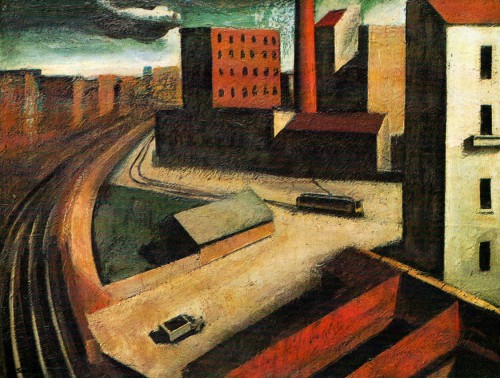

Mario Sironi

One of the ads for the final season of Mad Men read “Before feminism, there was Peggy”. This is the perfect example of the new origin fable. Radical feminism was only Peggy, trying to get promoted. And presto, the entire material history of feminist thought is reduced to a secondary character on an AMC series.

So, the filmic creation of place is, as I said at the very top, a complex of factors. But the reasons for its disappearance are growing, and there is something disturbing in the white baby boomer hipster University educated class now, in the U.S. and U.K anyway, in this visible loss of intellectual agency.

“All the ingenious devices of the amusement industry reproduce over and over again the banal life scenes that are deceptive nevertheless, because the technical exactness of the reproduction veils the falsification of the ideological content or the arbitrariness of the introduction of such content…Thought that does not serve the interests of any established group or is not pertinent to the business of any industry has no place, is considered vain or superflous.”

Max Horkheimer

Philipp Lohofener, photography.

The 21st century idea of individuality is now the crypto-conformist, a member of countless transitory groupings, many economic but many more the product of pop psychology, which is to say the manipulations of marketing, of medical or biological designation, created by a mental health mega-industry. This bourgeois individual is constantly fine tuning his persona in response to mass culture (which includes politics). The rise of the city, post industrial revolution gave birth to the early versions of the new conforming individual. And the idea of place, which had for a couple centuries, been linked to a certain kind of denial of immediate gratification in the interests of long term stability for family and group, provided a defining idea of a personal future. But this imagined future has gradually faded and in its place is the ‘dead now’. The imprint of instrumental logic has helped narrow the imagination. This is what alienation really is.

Radiator, Wittgenstein House, Vienna, 1926.

Walter Benjamin

That’s a famous quote of Benjamin’s, and it touches on the issues of space, and of place both, and of just how deeply and effectively the state and its propaganda (and mass culture following that lead) have colonized consciousness. The current culture industry products all operate within a deceptively constrained model of reality and behavior. And one that is consistent with the interests of global capital and of control. Universities and even high schools, arts institutions, all cultural bureaucracies operate under increasingly homogenized models of thought. Every official announcement of diversity when examined closely is actually doing the opposite, it is further homogenizing thought and values. Horkheimer wrote “The patterns of thought and action that people accept ready-made from the agencies of mass culture act in their turn to influence mass culture as though they were the ideas of the people themselves.” Nobody is allowed to get lost anymore. Getting lost is the final crime.

Great. I have a lot to remark but first have you seen Antonioni’s china doc? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PvTC1Db0WQs&feature=youtube_gdata_player

http://sensesofcinema.com/2013/feature-articles/when-ordinary-seeing-fails-reclaiming-the-art-of-documentary-in-michelangelo-antonionis-1972-china-film-chung-kuo/

I’ve always admired Antonioni, and Blow-Up is a film I’m deeply fond of, but I’d say the anti-Antonioni attitude these days has other explanations that are more nuanced than merely philistinism or anti-intellectualism as it exists not just in establishment circles but also in cinephile circles. You may want to track down Luc Moullet’s take down of Antonioni, even if I disagree. It’s merely food for thought. Here it is in fact: https://mubi.com/notebook/posts/rockefellers-melancholy

In cinephile circles, the criticisms often relate to the seeming ‘manneredness’ of Antonioni’s work, which is the opposite of what can be said for Fassbinder or Godard even. Many find his work precious and formally contrived, even if not necessarily contrived on a narrative level. It could be argued his films are self-contained in a way Fassbinder’s aren’t, as the latter’s films are chaotic and open ended like life itself. A certain camp of cinephilia contends cinema is the representation of reality, whereas Antonioni manipulates reality whereas Fassbinder does the opposite, delivering us reality as he perceives it. Fassbinder’s cinema is one of impression whereas Antonioni’s is one of ‘vision’. This not a take down of Antonioni on my part. I quite like his work, but I’m just examining why certain intelligent viewers may have reservations about his work. In short, many feel cinema shouldn’t be controlled, since reality itself is not manipulated or controlled. It should require an immediacy, an effortlessness and/or be chaotic. Antonioni is in many ways an anti-Godard as the former’s films are anything but ‘Brechtian’.

Many find his work precious and formally contrived, even if not necessarily on a narrative level. It could be argued his films are self-contained in a way Fassbinder’s aren’t, as the latter’s films are chaotic and open ended like life itself. A certain camp of cinephilia contends cinema is the representation of reality, whereas Antonioni manipulates reality. Fassbinder does the opposite, delivering us reality as he perceives it. Fassbinder’s cinema is one of impression whereas Antonioni’s is one of ‘vision’. This is not a take down of Antonioni on my part. I quite like his work, but I’m just examining why certain intelligent viewers may have reservations. In short, many feel cinema shouldn’t be controlled, since reality itself is not manipulated or controlled. It should require an immediacy, an effortlessness and/or be chaotic. Antonioni is in many ways an anti-Godard as the former’s films are anything but ‘Brechtian’.*

you know Remy, Id disagree with almost all of that. And Id certainly argue against that Moulett piece. But its an interesting article because of the ways in which it is wrong, the assumptions. Lines like “films about boredom are annoying”. What does that mean? Who decided Antonioni was about boredom? This is exactly the point ….well, one of the points, about this post of mine. The inability to read narrative, to see a film outside these very constrictive critical assumptions. He doesnt see how Antonioni is better (sic) than daniel mann? I could explain it to him, but this is just intellectual laziness. I actually find it too tedious to go on, but its a very juvenile sort of analysis, and reminds me a lot of the VICE and SALON writers when discussing art of any kind. The anti intellectualism is profound there. PROFOUND. A fear of seriousness in general. Antonioni is distrusted for, often, subtle reasons. The arguments are based on a faulty premise, or several actually. What makes Antonioni precious? What feature exactly? Wes Anderson is precious. No, I think its more about what is experienced on the margins of Antonioni’s films that make audiences uncomfortable. But you raise a valuable talking point and that is the idea of “realism”, which Ive written about quite a bit. What is unrealistic about antonioni in these terms? Fassbinder in fact shares certain things with Antonioni…..and Sirk looms here, too, in this discussion. Pasolini, as well. What really troubles Moulett isnt anything he says in that article, its that these films actually dont allow for easy analysis, more than anything else, and the specific ways in which they dont allow it are worth thinking about.

Its funny the Chinese gov was disappointed by the China doc because they didnt really get how auteurish it was, it made the country strange quiet myasterious boring in a trancy way — just as he makes everywhere!

So is it because the spectacle deals with abstractions (not with difference but “difference”, not with the concrete reality named by the weird depression but with ” depression” — or “poverty” or “transexuslity” in “prison”) that these effects can be produced, the impact of relating through the commodity image? (Even relating to oneself thru it?)

Peggy as feminism. She images feminism. She’s the action figure if feminism. But then the argument is extruded from the metaphor — say Peggy then become the chair of Pepsico..or whatever.

But the ruthless libertarianism of one level of all this shit is a cheezy allegory on another level…

@molly:

Peggy images feminsim. Exactly.

The quoting of ideas, this is actually something Adorno went on about, in a slightly different way. And its the heart of this issue I keep coming back to lately, the erasing of dialectics. Its not an easy discussion, but the cheesy allegory is sort of a topic, too. Its what nags at me, actually, the ways in which a Lena Dunham, for example., is fetishized, she is imaging herself in a sense. I watched the start of the 2nd season of Orange is the New Black the other day. I got through three entire episodes before I had enough. Its unwatchable. Its this same thing, this same class subjugation. And all of this stuff operates on the same level. This manufactured surface “realism’…be it comedy, or drama, or action, its all the same set of signs, of codes, and the foregrounding of western superiority, of white values. and of this accumulated notion of identity. They are instructing the audience in what is *real*, what they are to take as meaningful. As for Antonioni……that doc is amazing. Its quite moving actually. And yes, its very crucial to understanding his entire body of work. And perhaps thats been my point….Antonioni is doing something so very different. He is not making entertainments. And i continue returning to Pasolini in this. For he was shaped by not dissimilar forces and also was applying this rigour, this meditative camera and they end up seeming to me, now, to be films that are quite prophetic in a way. The fascist mentality one sees in Lena Dunham is being examined from within this very personal meditation — they are existential class analsysis.

John, how very interesting that you’ve written about Antonioni just as I’ve started watching his films. I watched L’Avventura for the first time a few nights ago, and it’s exquisite. Antonioni reminds me a lot of Borges in a certain way, at least as in their investigations of labyrinths – Antonioni the physical and architectural, Borges the psychic and paradox. In that scene on the Aeolian islands, when Anna first gets lost, the characters almost feel as if being transported to ancient times, they sense their own reconnection to the ancient Italian land and to its history (very much like in Rossellini’s “Voyage to Italy”), but they also feel “lost” in it, unable to find meaning. Look at that scene again and you’ll see characters crossing dimensional planes of space, wandering up and down, but always wandering, unable to stand still. Ironically, or perhaps not, Antonioni’s urban landscapes feel post-apocolyptic, as if the people don’t belong. People stand out in the frame, and it makes me think if maybe Antonioni is saying something about the land being alienated by people, not the other way around. The presence of people, of our history and culture, is a heavy burden on the land; much like language is to meaning.

Roberto Bolaño has said that the cities described in novels, at least in the good ones, are psychic maps of the city, and if one were to follow the novel’s map, one will most certainly get lost because it’s not an actual representation of the city, but rather the rendering of a space that evokes the soul of the city. Think of the Russian city (forgetting the name now since it’s late in L.A.) in Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment, Joyce’s Dublin, Bolaño’s own Mexico City, Cervantes’s Spain, Homer’s Mediterranean Sea, Twain’s South, Melville’s Atlantic, shit, even Dante’s physical rendering of Hell in his Inferno.

I greatly enjoyed this post and will share tomorrow. Next up on the Antonioni front La Notte. Looking forward to watching Red Desert and The Passenger again.

It’s not so much intellectual laziness on Moullet’s part as it is one accomplished artist merely having on idiosyncratic opinion on another great artist. Bresson and Truffaut were also Antonioni detractors. I’m not for the record. With that said, plenty of great minds make head scratching value judgments about other great minds. Nabokov didn’t like Dostoevsky. Adorno didn’t like Stravinsky. Tolstoy didn’t like Shakespeare. Bresson liked For Your Eyes Only. And so on. That’s all I would say to that.

That’s not to say Antonioni is without his philistine detractors, as philistinism is indeed a partial culprit. I’m not denying that. This is one of the most egregious examples: http://www.spectator.co.uk/features/77656/bergman-antonioni-and-the-end-of-an-error/

But I also think it’s worth mentioning that because great artists so often have such a particular and/or idiosyncratic, for lack of a better term, ‘vision’ they would like to bring to fruition their reactions to the works of others tend to be largely emotional as opposed to intellectual. I wouldn’t call it lazy per se but emotional, and they’ll often only praise works that subscribe to their particular vision of a medium. They don’t have the time or the mental energy to give the benefit of the doubt to something they don’t ‘get’. That’s a critic’s or intellectual’s job. So duh, Nabokov probably won’t like Faulkner, and it’s highly unlikely Tarkovsky would have much to say about someone like Howard Hawks.

@remy (and then joe)…………remy, look, its MY OPINION………so, uh, yeah, I think its intellectually laziness. Ive explained why ….at some length. So ….yeah, and i dont consider moullet a great artist. He was one of the VERY minor new wave directors. Its interesting how many of them have aged, in a sense. Straub seems more worthy, as does Godard in his way, while someone like Truffaut seems…well, skip truffaut…..he was always tedious……but Melville seems much the same I think….good, very good, but…but…. And then rivette is maybe less interesting. I dont know. Moullet is just minor. But thats hardly the point. Nor is the fact Nabakov hated dostoyevski. These are sort of cocktail party discussions. Look……….ive said what I think about Antonioni …at least in the context of his reception. Lots of people dont like him, Ive suggested why I think that is. And who and what I consider lazy criticism. Some painters can talk about painting, many cant.

my opinion.

@JOE.

yeah i saw you were doing your antonioni retro. But i had already thought about him because of this Belgian film. But its odd…zeitgeist. And i agree about the landscape. Its very much these figures in a landscape and both are dialectically related. Their lost-ness is the real topic here. I said at the end of this blog post…..getting lost in the final crime. And sure….; agree about maps.// THe situationists wanted to walk around Berlin using a map of Milan. Cognitive mapping. Something happened when man started to map things. The age of cartography. Ive always thought one of the pleasures of visiting new cities….new places….is getting lost. This exhilaration that comes from a not knowing which way to turn…..my hotel is……WHERE? There is archaic stuff linked to that. Memory traces that we dont understand. And I think antonioni gets that. I look forward to hearing your take on The Passanger and Red Desert, too.

John:

How do you feel about Manny Farber as a film critic in general?

@Remy.

I have a real soft spot for Farber, who went out of fashion, and for reasons that have validity. But still, he’s very worth reading I think.

What I feel aggravates Molly more than anything John is that in her eyes you seem to be overreaching for leftist or subversive undertones where there are none (i.e. in Pasolini, Beckett, or Antonioni for that matter), since the primary audience of these works is made up precisely of those they purport to be attacking. The bourgeoisie is really more “flattered” than offended by a film like Blow Up. Now certainly in Godard, Fassbinder, and Bunuel the subversiveness is there, but with respect to Antonioni I would say it’s up for debate. Antonioni’s a key figure, no doubt, but he’s not beyond reproach. Then again, very few great artists are, so…

Whereas much like Resnais and Bergman, Pasolini and Antonioni are seen to have fulfilled the roles of Euro-chic intellectual arthouse provocateurs, much like Haneke today. That’s not necessarily how I feel, but that’s how many others feel, and these are the same people who praise Bresson, Ozu, Renoir, and the like, not Coppola, Eastwood, or oh I don’t know Lena Dunham. So I’m wondering, how does rating Bresson or Renoir over Pasolini serve a ‘reactionary’ agenda in your eyes. The ones flattered by Euro arthouse-chic, and that’s not necessarily you, are the real reactionaries, because it’s tied to a naively Romantic view of the aesthetic object. It’s more Bertolucci than Straub or Rivette.

But really, my only gripe here is I feel you’re, unfairly or not, painting all detractors of a given artist with the same brush.

@remy. You’ve said this before. Duly noted. And I dont agree at all, but because your premise is so wrongheaded, it makes it hard to debate. Honestly, without meaning to be snide, but I dont know where to begin to explain all that is wrong with those three last comments. Suffice it say they are cliched thinking. And the very thing Ive tried to correct (in my humble opinion) is exactly what you refuse to see, or cant, or dont want to. I dont think you even understand what subversive is in this context, and…..oh, well, I dont know…..never mind…refer to the years worth of postings.

and what molly got to do with it>? And for fuck sake. Im going to regret engaging you here, but it makes my brain hurt when you say somethjing……”painting all detractors…with same brush” when ive taken the time to make clear in some detail what i have problems or disagreements with in each specific case. Look….i dont care if you like someone or dont like him. Its of no matter to me. There are implications, broadly, of course. but…. Go write about it, defend your position, start a blog, write a dissertation….I dont know. But you have to defend these kind of comments, and you cannot say I am doing something that its clear i am NOT doing if one just reads from the top of the page.

I just wanted to cut in with a slightly different angle on the topic. I can’t be sure how relevant my thoughts are to the topic, not being familiar with the films of Antonioni, but I’d just like to comment on the underlying assumptions:

The idea that his films could be “bourgeois” in its political orientation due to 1) subject matter and 2) an aestheticising treatment really links with the question of what is the nature of art. Now, I firmly believe that there is a big difference between saying “all art is political” and “art is all political”. It’s important to analyse the ideology behind works of art because modern day society encourages the opposite tendency of viewing an artwork as completely devoid of ideology; however, there is a distinction between that and *reducing* art to ideology. There will always be a residuum of aesthetic experience to any work that does not reduce to ideology. For lack of a better term, we can call it “texture”. The “texture” of an artwork can relate to the ideological “message” behind it, but it’s also something more or something apart. And when we say that something is beautiful, while it is true the judgement has a political element to it, I think there’s also an aspect to aesthetics that can’t be quantified under political ideology. It is a sort of contemplative, personal experience. And it links with the idea of solitude. It’s true that human beings are political creatures, but they are also solitary creature. And the non-political residuum could be traced to the idea of solitude, I think. The ideological part of art ends where human interaction with one other ends, while the aesthetic residuum of “texture” starts where introspection and human solitude begins.

So in terms of whether the subject matter of a film makes it Marxist or reactionary or etc., I think we do have to avoid the trap of drawing too literal and too direct a connection between ideology and subject matter. After all, a work of art is not a tract or essay, so the function of “theme” becomes very different, I think. So just because a work of art deals with, say “bourgeois malaise” doesn’t mean that the ideology reflects the bourgeoisie. And whenever a work of art refers to the concrete social reality and the underlying class structure, that structure is not treated literally but metaphorically. It’s similar to what Remy said about a landscape of a novel never really being the literal MAP of the location, but rather something allegorical. It’s the same with the presentation of class structure — if a work presents a certain class structure of society in its subject matter, its meaning is not literal, but acts as a referrent with a very different significance than “real life”.

The reason I think this distinction is important is that otherwise you can easily fall into the trap demonstrated by “mainstream liberal” media, which is the tokenizing or brand view of subject matter. Oh, OITNB is set in a woman’s prison and depicts prison life, so it must be an expose and revelation of a certain social problem related to prisons. Or, its an all-female cast so it must be feminist. Etc etc. ANd this leads to the facile sort of “identity politics” (I’m using the term the way Naomi Klein discusses it in “No Logo”, from a leftist materialist and anti-atomizing perspective, rather than what conservative culture warriors mean when they use it) treatment of representation that is all-too-literal — we don’t have the right percentage of a certain identity demographic represented in media, so the problem will surely be completely solved if we just had more media with women/minorities/LGBT people! ANd that misses the point because, although representation matters, it never matters in a *literal* way. You can’t just count percentages and come up with a direct correlation to the progressiveness/regressiveness of media.

As for the question of aestheticism, I think that what Marx wrote about Greek literature (I think in “Critique of Political Economy” if I remember??) is very relevant. I was quite surprised when I first read it because it was something I never expected Marx to write. It was a sort of defense of classical literature, and an apology for the hierarchical aristocratic subject matter that it treats on. And his point is that the correlation is never literal. So this is an example of the quite ignored side of Marxism that’s not merely “vulgar” materialism. The way I see it is that, although Homer seems to show us a hierarchical world with no alternative, in some way his work IS radical because of its aesthetic structure — it shows us a world where the strife between Sparta and Troy is ultimately futile, ending in a battle where nobody really WINS, and so, without referring directly to any ideology, it does actually work radically to pull the ground under the society it depicts, as it were, and show us how contingent and how tentative the foundations of the society really is. And it does that through an aesthetic route rather than a political route, as a philosopher would do.

… I’m not sure now how this relates to Antonioni. But I guess this is a way of showing how “bourgoeois” art could be seen as radical, if analysed a certain way.

http://www.academia.edu/1177793/The_Return_of_1960s_Modernist_Cinema

For the record, I’m not trying to be combative nor am I offering a value judgement on Antonioni that differs from yours but am merely offering an opinion on why I feel Antonioni may be out of fashion in certain circles. We’re free to agree to disagree.

@exir

I think that was Joe who mentioned mapping and allegory. Anyway………..i agree and its a big part of what is driven a lot of my writing on art. Its astounding how confused people can be about this. Form and structure. That marx quote isnt surprising, or rather it is, but less than one might think. Adorno, Horkheimer, Freud….i mean they came out of a certain european culture that had significant virtues….virtues lost now and which they saw erode. Ive always thought that without some understanding of classical literature, one cant understand much of the society one lives in today. Virgil, Dante, Shakespeare, Marlow, Spencer, Milton, Cervantes……….Ovid, etc. And its interesting because i watched Aronovsky’s Noah last night. Its a very strange comic book rewrite of Genesis, essentially. With Tolkein tossed in, and in one way, it could be compared to a 21st century version of The Ten Commandments I guess, except there is something even more infantile going on. And its partly the comic book visuals, but its also the idea of hero…but most of all its the form of the story. The story is now Genesis , a page one rewrite from Showtime, to turn Noah into a sci fi series. And it is this form that expresses the ideological meaning. The form of the story, or rather the fragment of a story, emphasizes this incomplete backstory, interrupted, and sort of always ending in a brutality. You are being watched…its ok….the watchers (which they are literally called) have power.. The ideology of Noah is Obama’s surveillance state and prison system………and no matter how away that is in content, in form its not far away at all. If Aronovsky thought he was making a modern parable about the environment…which im imagining he did…what he actually made was a strange onanistic (sic) narcissistic and authority worshiping validation of authority.

@remy:

here is a quote from that hamish ford piece you linked:

“P. Adams Sitney highlights modernism’s unstable operational space some- where between classicism and the radical avant-garde. In his book

Modernist Montage, examining the nexus between literary and cinematic modernistforms, Sitney argues that ‘the central conflict within modernism has beenthe opposition of a visionary quest for revolutionary newness and a continu-ity with a classical tradition’ ”

This is the university version…radical or revolutionary “”newness””…that sort of cleanses it of, well, revolution itself. In fact that newness, (and yeah sure there were four or five branches of modernism) was a reaction to and corrective of conformist state agencies, and the attendant oppression of daily life. Its not some essential quality of *new* that we’re talking about here. This piece by hamish ford strikes me as what one might find at most film departments in University. Its just so generalized, and so often wrong. You cannot CANNOT lump Bergman in with Pasolini for example. It ignores crucial aesthetic beliefs, and both had entirely different projects, and just because they fit the calender that says oh, MODERNISM…60s modernism., doesnt mean that they can be spoken of as part of some imaginary periodic framing. I dont know man, it just strikes me as rather shallow. Its good to know of, though….it is, honestly.

Speaking of film critics, do you know of any consistently good film critics writing today, John? Most of what I read on movie websites doesn’t do much for me. And when ‘Film Crit Hulk’ gets published in the New Yorker ( http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/culture/2012/05/the-hulk-on-mark-ruffalos-hulk.html ), you kind of just want to give up all hope.

I like Jonathan Rosenbaum. I haven’t read much but what I’ve read is usually good. Mainly I think his critique of the superhero genre is spot on, and he went against the mainstream flow in rating schlock like Dark Knight quite lowly, so I’ll give him that.

geoffrey o brien on film is great, but he’s not a regular critic.

John:

I’m assuming you aren’t a fan of Rosenbaum?

Here is rosenbaum’s ten best list for 2012……

The Turin Horse – Béla Tarr

The Forgotten Space – Allan Sekula and Noël Burch

Bernie – Richard Linklater

The Hunter – Rafi Pitts

The Kid with a Bike – Jean-Pierre & Luc Dardenne

Unforgivable – André Téchiné

Holy Motors – Leos Carax

Moonrise Kingdom – Wes Anderson

The Deep Blue Sea – Terence Davies

Gerhard Richter Painting – Corinna Belz

Its not a horrible list, but its weirdly predictable somehow. Creepy predictable. Bela Tarr…..well, whatever….I love My Balalaika part six. I often felt if Tarr hadnt existed, film schools would have invented him. Wes Anderson is just egregiously bad taste in my opinion. The Sekula is a documentary (fascinating one)….ive not seen the Richter doc../..but i suspect its worth seeing. The deep blue sea……….arrrgh…..well, i think itts junk and i think Linklater is very pedestrian middle mind stuff.But at least he DIDNT have Shame, or Dark Knight, or Argo, or even Amour. And that suggests something on the plus side. If i had to do a 2012 list, it might only be four or even just three films long. The Master would be #1…. and maybe The Hunter (although in most places i think thats 2011)…..then in 2013 Rosenbaum had Fruitvale Station as best film of year. Which i found unwatchable. In a year with blue caprice, thats very odd. For me anyway. So no, I guess I dont like him much. I think armand white is often funny and sharp as reviewers go. Curtis White is great, when he occasionally writes on film.

I’m surprised you’d have kinder words to say about Armond White, since his tastes tend to be just as if not more suspect on occasion. But I’m mostly rankled by White’s “reactionary conservative masquerading as iconoclast” shtick where he constantly feels he has to “set the record straight” and “tell it like it is” even if that means throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

People like Rosenbaum and J. Hoberman are far more sincere in their respective approaches. Whether you agree or disagree with their value judgments on specific films is besides the point.

Armond White is a *reviewer*. But he is often the sanest voice on certain pretensions….his review of Slumdog Millionaire alone makes me like him. He is what he is, but as for Hoberman……….well, we just disagree. Im not sure you can argue about sincerity. Why does hoberman strike one as more sincere? And of course their value judgements matter. What else does matter, in fact?

John:

I don’t think anyone who posts on your blog is going to disagree with either you or Armond White on Slumdog Millionaire. But I do have issues with the whole idea that there are say 15-20 filmmakers or 20 novelists who really matter. And that one need not bother with the rest, because they’re “minor”. It’s constricting and preaches ignorance. It’s anything but open-minded. It’s received elitist wisdom. It’s the attempt to create some ossified unassailable canon of “high culture”. Am I supposed to take White seriously when he proclaims the preference for Naruse over Ozu is mere pretentious postmodern affectation. That’s the best he can come up with. Should we just say if art doesn’t do this, this, and this it fails. It’s not so binary. There are great works. There are good works that are flawed but still have something to offer. There are even mediocre works that are deeply flawed but still have something to offer, and then there are blatantly bad works.

In short, White’s review of Celine and Julie Go Boating is precisely what I find problematic with him, posturing as the “anti-relativist voice of reason and discernment”. It’s basically Roger Scruton on the left.