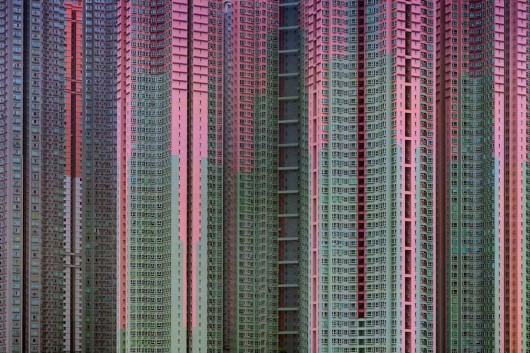

Michael Wolf

In clinical pictures of schizophrenia, according to Gabel, “a degradation of the dialectic of the totality (of which dissociation is the extreme form) and a degradation in the dialectic of becoming (of which catatonia is the extreme form) seem to be intimately interwoven.” Imprisoned in a flat universe bounded on all sides by the spectacle’s screen, the consciousness of the spectactor has only figmentary interlocutors which subject it to a one-way discourse on their commodities and the politics of those commodities. The sole mirror of this consciousness is the spectacle in all its breadth, where what is staged is a false way out of a generalized autism.

Guy Debord

The topic of political art is a highly contested area. And since the Tate Liverpool has just mounted an exhibition called “Art Turning Left”, it is worth looking at all the things wrong with the Tate exhibit, as well as a lot of critical writing on the subject. Of course, the first response to the Tate exhibit is ironic laughter. And it does approach self parody, one has to say. Even the title is a parody.

But the question of politics is significant in cultural terms. The problem is that, as an example, if one looks back at the “culture wars” of the 90s, in the U.S., what one saw was a conflating of several things and a mystifying of social domination, a fetishizing and reifying of ‘otherness’, and finally an art of personality. Kara Walker being one artist who capitalized on identity art, and one that serves as a usefull model for some of the problems embedded here. The flip side, at least to some degree, is Fred Wilson, whose work I find haunting, even mysterious, while still being overtly political. The problem with identity politics in art is that it does nothing to alter the art market, which is run by the same wealthy white men who have always run it. To create art that is part of the exchange value that institutions of culture traffic, is not exactly the intended political message. But as I continue to point out, therein lies the problem (or one of them) with message.

Moving forward to the mid 90s, and, really, on through the current show at the Tate, what can be seen is really just the reification and commodification of parts of the 3rd world. It is colonial subject as fashion.

Fred Wilson

The invention of museums, of curated shows of “artworks” is a European bourgeoise phenomenon. The idea of biennales starting up in Qatar, or Senegal or South Korea or Porto Alegre, is terrific, except that they are modeled on, or are constituted as reactions to, the established European white model (the organic community gatherings of, say, Benin, are not being reproduced in London or Antwerp or New York or Madrid). African masks from Chad or Gabon are better appreciated in a context that is formed by indigenous culture, not by presenting them as competition to Rembrandts or Titians in western white museums. The African mask evolved through specific historical cultural practices, non European practices, without ever intending to be a cultural commodity for rich white people…or a commodity for anyone, really. And herein is a problem with all colonial cultural production. Or post colonial, really. The rise of conceptual art seemlessly attached itself to the rise in bienalles and elite art fairs. And installation art, which originally posited itself as anti commodity, became simply another kind of commodity. And the third world artists presented in bienalles throughout the world, were still, in the end, working with the point of view of the colonizer, of the Euro centric tradition, and more importantly, were not really creating art. Conceptual art is vaguely interesting, if one chooses to discuss it. But there are no artworks involved. Julian Stallbrass wrote: “The filtering of local material through the art system ultimately produces homogeneity. The system – not just the curation but the interests of all the bodies, private and public, that make up the alliances around which binanales are formed — tends to produce an art that speaks to international concerns. More specifically it reinforces neoliberal values, especially those of the mobility of labor and the linked virtues of multiculturalism.”

What is the difference between Kara Walker and Fred Wilson, as an example. I would answer that Wilson’s ‘message’ follows after the inherent mysteries and sensuality of his pieces, while Walker makes nothing much worth really experiencing. She has a point, a message, and its valid, but the artwork is only there, in the shadow of message.

Aztec mask, Central America

The problem is that conceptual installation “art” is not art, really. Its installation essay. For there is no aesthetic or sensual experience of the artwork, only a viewing and a discussion. There is a stand-in for an artwork, which can be ‘unpacked’ later. Now, that may often have value, but in this context it is quite easily hijacked for the purposes of the ownership class. Because such work has no autonomy (more on that later), and because, finally, it is almost always predicated, admittedly paradoxically, on a western naturalist idea of the ‘real’; it is rooted in propaganda and one dimensional message, and because it assumes agreement about a number of perceptual points, the result is uniformally reactionary. Creating message will tend to instrumentalize the process of message creation. This is, in the final analysis, why art is not about message or fomenting revolution. It is about awakening. Individual and by extension, community. But if you want to change Capitalism, then certainly art matters, but not it’s message per se. And on a simple level, this is because EVERYTHING can be a commodity and everything IS a commodity.

Gabriel Orozco

Damien Hirst

Robert Bly once said ‘all learning takes place in ritual space’. It’s a deceptively profound remark. This is the juncture where academia enters the discussion. Today, the MFA programs in any of the arts, but certainly in fine arts, is a training in the secret hand shakes of a rarified preist class. It is learning the grammar and vocabulary of exclusivity. And by extension it is the learning of class distinctions. For Universities are complicit to a high degree in the selection and grooming of future money makers (which means the exclusion of voices deemed too radical). Does one think Damien Hirst is just simply more “talented” than anyone else graduating that year? Of course not, but he possessed a collection of personal characteristics and personal background qualities, and a personality that was deemed acceptable, and he, all on his own, had a talent for positioning himself. Now, I have always had a problem with flattery. Partly because I am sure I am succeptible to it, but more, because it is such a diabolical weapon. Those who learn flattery, always do well.

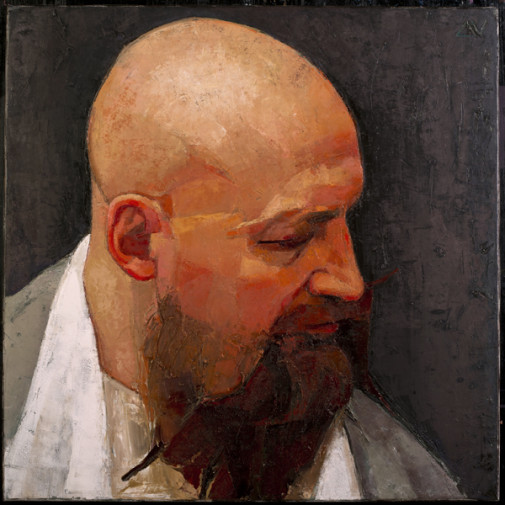

Diana Vouba

This dilemma, or contradiction, is at the heart of discussing art and politics. The ritual space of formal aesthetic consideration is a significant need. The truth is, of course, that schools such as Bauhaus or even textile work from the Workers Union, or the attempt by William Morris and others to create autonomy, were eventually defeated by the forces of repression and capital. What survives today is mostly a market friendly training ground for the next Hirst or Koons. The work that came out of the Bauhaus was craft oriented, and certainly also focused on architecture, but altogether there was an aesthetic vision about life. There was also an implicit pragmatism. And crafts, and architecture differ from what has come to be viewed as ‘high art’. Or fine arts, and that distinction is worth thinking about because today it serves only a very regressive purpose.

http://www.vam.ac.uk/page/w/william-morris/

Museums of thirty years ago seem almost quaint in comparison to the Corporate branding and Vegas-like strategies for attracting audiences that exist today. The Guggenheim is now a franchise museum. There are corporate tie-ins with various artists (sic) like Hirst and Murakami. Curators are a good deal more like Hollywood producers than anything else. But these are crass and obvious expressions of a hyperbranded culture. There remains, certainly, something to be said for the few remaining museums around the planet that offer simple contemplation of artworks. But that still begs the question of this idea of the purpose of art. And the political purpose. Julian Stallbrass points out that it is art’s very exclusivity that attracts corporate sponsorship, and the taint of crass mass culture (Madonna announcing the Tuner Prize in 2001) and recent associations with Fashion designers makes short term financial gain but erodes this sense of exclusive and rarified elite privilege. The problem is that the notion of exclusivity has both a progressive and a regressive side. The regressive is obvious; the class segregation and control of vast amounts of capital. The progressive side is linked to the sacred and ritualistic contemplation of form, the social questioning that clings to the mysterious forces of image. And the problem with this progressive side is that it has for so long served to reinforce the status quo of inequality and domination. Contemporary art is now so intwined with corporate money, and the establishment curators and museum directors so ingulfed with sponsorships that in fact very little exclusivity remains. Additionally, the moment that conceptual art gained traction, something else was allowed to recede, and that was the experience of the artwork. This connects to my last posting and the vast cyber attention economy, the system of domination which has now layered ‘all’ experience with a sort of neurological numbness. The mandate is to keep people ‘looking’ all the time. Microsoft and Google rely on the constant circulation of image. And this manufactured anxiety about missing something, this created sense of urgency to keep watching, to keep checking, has sort of branded visuality itself. The attentive ‘looking’ of forty years ago, at museum art, or at movies, or in theatre, is now a sort of personal surveillance system. And this is probably one of the reasons for even the left to operate in exercises of shaming, policing, and scolding. Image is everything. And the impulse to puncture pretension is really just rebranded snark, and it all serves the endless constant numbness of telecom dread. The big corporate giants of the communication industry are at work to capture your gaze and attention. And they dont really care if that attention is attenuated. They measure success by how long they keep your gaze, and the ideal is to hold your gaze, all the time. This aggressive capturing and manipulating of vision must result, eventually, in the quality of gaze deteriorating. People are rewarded for just looking, not for how well they look.

With concept art, and installation art, the quality of close visual examination (and the attendant mimetic narration) isnt needed. Its enough to take it in, the way one might glance for a moment at a dog food display.

Candida Hofer

The process of image circulation, coupled to the consensus on viewing “events”, whether the Super Bowl or World Cup, or just the latest Beyonce album talked about on social media, has been just one thread in this hyperrealism of daily life. Art has never been very good (more on that in a second) when it serves as propaganda or message. But the cyber attention apparatus is now attached to a culture of surveillance and totalitarian state policing. The ability to follow complex narrative, for example, is all but gone, and more significantly, the ability to mimetically enage with narrative, or image, or nature, or, really, anything, has atrophied for the mass public. What has replaced this sense of inner life, is a vague sense of disquiet and unease. The screen addictions of the populations of the West now seem very much a personal super ego (per Jameson).

There is another aspect to a museum culture, and that has to do with modernism and its Hegelian idea of future resolution. Boris Groys wrote: “But today, this promise of an infinite future holding the results of our work has lost its plausibility. Museums have become the sites of temporary exhibitions rather than spaces for permanent collections. The future is ever newly planned—the permanent change of cultural trends and fashions makes any promise of a stable future for an artwork or a political project improbable. And the past is also permanently rewritten—names and events appear, disappear, reappear, and disappear again. The present has ceased to be a point of transition from the past to the future, becoming instead a site of the permanent rewriting of both past and future—of constant proliferations of historical narratives beyond any individual grasp or control. The only thing that we can be certain about in our present is that these historical narratives will proliferate tomorrow as they are proliferating now—and that we will react to them with the same sense of disbelief. Today, we are stuck in the present as it reproduces itself without leading to any future.”

Concurrent with financialized capital, cyber abstract capital often, the giant electronic media apparatus, and social networking, has seized attention, and has held it, managed it, and extracted profit from it. The problem with contemporary art is that with the loss of experiencing the artwork, the evaluation of image, the gaze, is reproduced on Youtube, twitter, Secondlife, etc, and almost anything on youtube or myspace is indistinguishable from installations at MOCA or at the Venice Biennale. The only difference is that one is AT the bienalle. One is in a corner of LACMA. Or one is *curated*. The point here is that the vast quantity of ‘artworks’ has left criteria for evaluation eroded, and when anything can be an artwork…if I say so, on facebook or youtube…then ritual space, the location of learning, has left the building. The building that is our understanding of society. Now the argument FOR conceptual art is that it is about *relationships*; those of time and text and video and audio tapes, between found objects and chance. All of which is interesting to talk about, and positing the immaterial as intellectually relevant is even fine, but one is still faced with a disconnect from experience. And when a culture accepts experiential disconnect, we are entering a very weird place. Now, the concept art movement, of at least practioners within it, continually asked the question ‘what is art and what are artists?’ Their position was, to put it reductively, that modernism was an aesthetic gaze on the ‘art thing’, the object, and that aesthetics was positing the role of the spectator as constituative to art. This is in fact rather obvious, AND circular. You cant get away from an object and someone looking at it. It might be on youtube or it might be even reading text, or it might be some site specific experiment on a street corner, but someone is watching or listening to someone else. There is never an escape from this. The rhetoric of conceptual art would suggest the ‘idea’ starts the artwork and the spectator , the gallery visitor, finishes it. But the key word there is “it’. Finishes “IT”. What? Oh, the artwork. From Kosuth through to Abramovic, there has been no loss of exclusivity. Money changed hands, galleries made money, people made a profit. And even the, in theory, political conceptual artists, were making money for the same people that Jackson Pollock made money for, and the same people Picasso made money for and the same people Mattise made money for. If anything, the conceptual art movement ended up more reactionary in its effect, not less. If Marina Abramovic is any indication, then all of this posturing ended with only better more profitable brands. An aesthetic education is the precondition for radical vision, not the losing of aesthetic education. Here is the, perhaps, core delusion of conceptual art.

There is a sort of confusion of terms in all this. Form and content, for example. When you walk into a gallery, and there is an installation and that installation is by an artist who is concerned with “content”, not with form; this would be typical of a conceptual artist. But the experience of those coming to the gallery has no aesthetic content, or none beyond the comprehension of the installation’s message, and that is not really an aesthetic experience (note to self* define aesthetic experience below) . The missing element in a sense is narrative. If the artwork has lost all narrative potential, then it is mere propaganda. It is advertising. And it is likely MORE not less reactionary in terms of political effects.

But there are signs that potentially important work is starting to be developed. And more significantly, that it is linked in various ways to the idea of schooling. This seems to me vital in finding a way out of the oppressive tedium of the culture industry. This exhibit from Austria, which includes theatre and music and a good deal of critical commentary, social and economic theory, and aesthetic education feels like a model worth following

http://www.steirischerherbst.at/2013/english/

Kuwait Stock Exchange, Andreas Gursky

As a footnote; there are artists lumped into the conceptual basket (Richard Prince, or Hans Haacke, or even Robert Gober, Ann Hamilton, and Bruce Nauman) that probably deserve their own basket because in a sense, like Fred Wilson they are making artworks, and those works tell stories of some sort. Gober’s sculptures are eerie crime stories, even if curators want to make him a carrier of message “about the body”. And there are the sui generis Trevor Paglen, and Jane and Louise Wilson, both of whom could be, concievably, described as conceptual…but I’d argue are nothing of the sort. Many conceptual or installation artists will often be described as exploring identity, or time, or gender, etc. This is the sound of catelogue or exhibit prose. Well, ok, but honestly, since man first crawled out of the primordial swamps and starting making mud balls and scratching walls, the work done could be descibed as exploring identity. And EVERYTHING since could also be so described. In fact find me an art work NOT about time and identity and gender? Its just really reached a level of absurdity at this point that approaches collective madness.

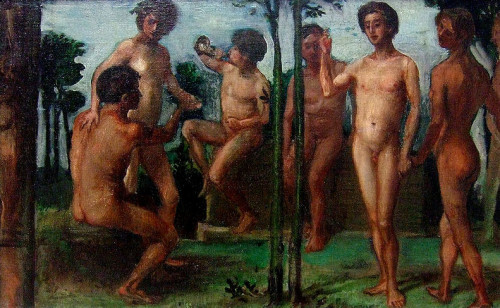

Hans Von Marees

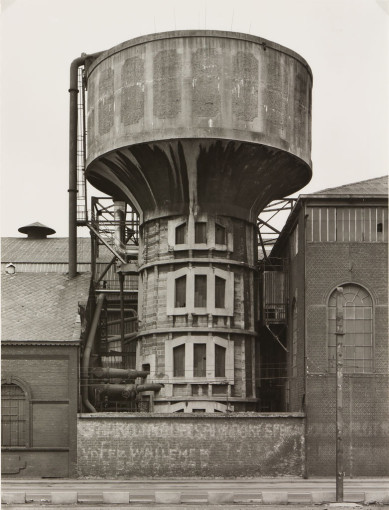

Let me touch on contemporary art briefly, again, from the perspective of the political, and sort of recap a bit. Installation art — much of it overtly “political” in intention, is by my definition almost always superficial. But I do accept that much of it, especially from places not previously allowed visibility (South America, Africa, South Asia) served as a partial, and brief, corrective of some sort. But this was counter balanced by the subsumption of this work by White European Imperialist institutions. In fact, the appearance of this work only happened because of counter forces in these institutions, e.g. corporate penetration and marketing. Art that says, here, look at this population, which has been invisible, is good on one level, but it’s not a very deep experience aesthetically. Maybe it was never meant to be, and maybe that is OK. But like all correctives, installation or envioronment art quickly enclosed itself in a very tight aesthetic cul de sac. It was also quickly commodified, inspite of its best intentions. But it is worth looking at trends in art writing; Stallbrass, Arthur Danto, and even the idiotic Dave Hickey. But one could include Hal Foster and Margaret Iversen. The problem with all of them, save Iversen perhaps, is that they establish sort of principles, and stake out positions based on these principles. And then seem not to notice that individual work, individual artists defy these categories. When Stallbrass discusses photographers such as Thomas Ruff and Andreas Gursky, and describes them as eliciting wonder rather than critical questioning (as did earlier art photographers, going back to Sander) he is doing something rather dubious, intellectually. It might be worth mentioning, indeed as he does, that Ruff and Gursky, and Candida Hofer all studied with Bernd and Hilla Becher at the Dusseldorf Kundstakademie, but his conclusions seem puerile and general. But then it’s maybe that I happen to think highly of all those photographers, and additionally see their influence as productive of a radical vision, not reactionary. Hofer’s series ‘Architecture of Absence’ is, in fact, one of the more disquieting books of photos I can think of in the last thirty years. It is allegorical, and its missing inhabitants are interrogated in absentia, for the viewer knows crimes haunt these spaces, the ghosts of accumulation. Still, Stallbrass is a keen analyst of the dialectic between business and culture:

“We have seen art’s uselessness — its main use — is being sullied by the particular needs of government and buisness. In a linked development, art’s elitism is challenged by the attempt to widen its appeal: business values art for its exclusivity, while states are generally interested in the opposite, and wish to widen its ambit. Finally art’s means of production, increasingly technological, have come into conflict with its archaic relations of production”.

Stallbrass quotes Adorno at the end:

“Absolute freedom in art, always limited to a particular, comes into contradiction with the perennial unfreedom of the whole.”

Hilla & Bernd Becher

This is, of course, the issue in a sense. The essential first question. For Stallbrass, the openings to utopian anti instrumentalism, is compromised until the unfreedom of the whole is gone. I would argue, that whole cannot be fully recognized without the openings provided by the shock of art. One cannot do without it, and to try is a disturbing sort of Stalinist factory sensibility. And this takes me back to the top, and notions of collectivity. Obviously the cult of authorship was always going to mediate notions of the collective. But the best work, from Rubens to Goya, from El Greco to Eakins to Noland and Rothko, all feels connected to history, for it all was questioning its predecessors, and itself. The anti intellectualist populism of writer/critics like Hickey, is an indorsing of the fan model of appreciation. You dont need to “know” anything, just enjoy, or not. This is the ad man’s dream. Marketing would pay Hickey to keep spouting that stuff. The philistine loves his own impulse shopping. He doesn’t want it impugned. It is also an endorsement for hobbiest artists. And this is a contested topic as well. For what seperates the hobbiest from the professional? Or corporate kitsch from more ambitious work? The term professional, in fact, needs to be retired. Lets just say the serious and the unserious.

The normalizing of seperation is aided by mass media. Everyone watches the latest episode of whatever, and feel as if they are part of this group, this very large abstract immaterial community of viewers. This is what popularity does, in a way. It is why the public gravitates toward the already popular. It means you can belong to this group. You are accepted because you pledge alligance to the same brand. You share nothing except the information of viewing. To allow for a sense of purpose in the audience, the products now increasingly provide their analysis in the narrative itself. It is an auto critique in a sense. The corporate TV product (film, too, but it is more acute in TV) contains within its presentation and story a clear set of indicators about how to feel, and what to talk about when you do talk about how you feel. Characters will look other characters and tears well up. Looks exchanged. And the camera is usually subjective during these scenes. The audience knows,’ah, this is where we cry and this is for whom we cry’. Often characters will be flat out recap the story and intended message. The point is, the perspective for approval is pre-contructed. The assault of the media apparatus plays a role in how the public “sees” art. How it reads the simplistic narratives of Hollywood and TV. It plays a role in a mental numbness, a false sense of community, an almost, as Debord said, generalized autism. The electronic attention economy keeps individuals seperate. Art, not concept, but art, brings people into contact.

Giovanni Baglione , 1602

A next to final note here on an interesting piece by Greg Grandin, on Herman Melville’s novella, Benito Cereno. One of the reasons Melville endures and actually grows in stature as times passes is that he so deeply understood the dark soul of society. Far more than Conrad, really, Melville grasped the inherent toxins of western industry, and its violent by products, such as slavery.

Grandin ends his short cogent piece on the novella with this:

“Melville’s tale describes the deep structures of a racism that were born in chattel slavery but that didn’t die with it, a racism that, in the United States at least, was grafted on to, while at the same time disguised by, a potent kind of individualism, a cult of individual supremacy, based not only on the fantasy that some men were born natural slaves but that others could be absolutely free.

A feeling of dread permeates Benito Cereno that the fantasy won’t end, that after abolition, if abolition ever came, it would adapt itself to new circumstances, becoming even more elusive, even more entrenched in human affairs. It is that foresight that makes the story, compared, say, with Uncle Tom’s Cabin, so enduring a work of art.

The events that inspired Melville, not just the ruse but the broader history that led all involved, both the deceived and the deceivers, to the Pacific, reveal the extent of the fantasy, the ways in which “free trade in blacks” served as a force multiplier. It took slavery’s original deception and insinuated it into every aspect of New World life and thought.”

If one is to discuss the purpose of art, or its politics, then one could do worse than to look at Melville’s body of work. Moby Dick is, of course, one of the greatest novels ever written, and maybe ‘thee’ greatest. But Confidence Man, and several of the shorter novellas, Billy Budd certainly, and Bartelby the Scrivner, are almost as significant. But the one book that has always loomed as the darkest of narratives is Benito Cereno. But it is a novel that does not have a real message. It is a dark mysterious book of forboding and an almost religious anxiety. A Kierkegaardian dread, a sickness of the soul. Grandin’s summation is precise and perfect in a way. But those deep structures of racism are revealed through the depth and density of the prose.

Northern Qi dynasties (550-577) (The Lost Buddhas of Qingzhou)

From the first page, this paragraph…

“The morning was one peculiar to that coast. Everything was mute and calm; everything grey. The sea, though undulated into long roods of swells, seemed fixed, and was sleeked at the surface like waved lead that has cooled and set in the smelter’s mould. The sky seemed a grey mantle. Flights of troubled grey fowl, kith and kin with flights of troubled grey vapours among which they were mixed, skimmed low and fitfully over the waters, as swallows over meadows before storms. Shadows present, foreshadowing deeper shadows to come.”

and as the Captain watches a strange ship approach, as he sits in the harbor…

“With no small interest, Captain Delano continued to watch her- a proceeding not much facilitated by the vapours partly mantling the hull, through which the far matin light from her cabin streamed equivocally enough; much like the sun- by this time crescented on the rim of the horizon, and apparently, in company with the strange ship, entering the harbour- which, wimpled by the same low, creeping clouds, showed not unlike a Lima intriguante’s one sinister eye peering across the Plaza from the Indian loop-hole of her dusk saya-y-manta.”

This is, to me, what art does. One could easily say a strange sloop approached slowly through a dull morning fog. One sentence. That is a lot more efficient.

James Kavenagh wrote of the central character of Delano:

“The character of Delano, then, can be read as a textual figure of an ideology in crisis. For Delano, the crux of the problem is to reconstruct a confirming “reality” of power and authority—the “natural” authority of racial superiors (whites), and the political authority of social superiors (Captains, “gentlemen”). The whole scene aboard the San Dominick appears as unsettlingly “unreal” to Delano because it presents an image of social relations that lacks the appropriate materials for any “reality” he can construct. Thus, Delano’s anxieties center on loss of control—either his possible loss of the Bachelor’s Delight, or his perception of Cereno’s loss of control of the San Dominick; what most confuses Delano about the scene aboard the San Dominick is the absence of the network of repressive practices and apparatuses that would ratify his own heavily imaginary sense of himself and of reality, that would reproduce the ideology (the “lived relation of the real”) which would make his world look as it should.”

Melville always understood the delusions of the Puritan American mind. He understood the misery and violence born of a trust in dogma, in Church and state. It it to little purpose to unpack the symbols and shifting tones in Melville. The whole is always greater than the sum of the parts. The whole, the great tragic portents of death and decay, and of individual loss and failure and confusion, somehow mean more than any crisp detailed dissection of Melville.

David Reed

A final note on a very good film that just came out, The Hunter. Directed by Australian Daniel Nettheim. Set in Tasmania, the skelton of the plot can be described simply: a mercenary hunter (Willem DaFoe), is hired by a bio tech firm to find and kill the last remaining one or two Tasmanian Tigers (a species of marsupial that officially was listed as extinct in the 1930s). Such a description, however, tells one very little about the real feeling of this film. The symbol of extinction looms like a horrible toxic shadow over the wild landscape, the site of a the near complete genocide of Tasmanian aborigines 150 years earlier (http://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/anonymous-tasmanian-genocide). The feeling of loss permeates the film. As does the professionalism of violence. Remarkably unsentimental and spare, the narrative plays out in DaFoe’s ever more rigid facial muscles, his body tense as he surveys his own fate reflected in the uncertain relationship he develops with a family at the defacto lodge, and his wonder that one of the Tigers might still exist. The missing population of the island is embedded in the lonely last female Marsupial carnivore. It is a dark meditation on Darwin, manifest destiny, and patriarchal sickness. Guilt haunts the inhabitants, almost as it does in Bad Day at Black Rock. The unconsiousness of history does nothing to alleviate the feeling of failure in this economically forgotten corner of the world, there is no bliss in the collective ignorance. It is a film of ghosts, and of the smallness of man adrift in this most wild of landscapes.

The Hunter, Dr. Daniel Nettheim 2013

*Aesthetic experience is, as a short answer, that which triggers reverie. And to do that, one has to trigger a mimetic interior narrative. Adorno compared it to an experience of mourning after loss. It is not cognitive. Or, it is not THAT kind of cognitive. There are no answers, only questions. But more on this in coming posts I hope.

There is another aspect to this discussion. I was focusing on trends in artworks, and in especially on the fine arts market, painting, sculpture, and installation art. Gallery art and museums. And the de-experiential part of that. But there is another area directly linked to economics. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2012/jul/30/review-threatens-french-creatives-benefits

the idea in many countries, certainly the US, but now in Norway even, with a right-ish business govt in place, is that arts are a business. And a profit is the goal. It promotes the cutting of all state subsidies for the arts. Elite institutions are privately funded, usually, and even then, not totally safe, but still, compared to regional smaller festivals and companies, they are relatively secure. The smaller concerns, and individuals, rely on state funding to a large degree, often. Promoting profit as the criteria for cultural excellence is now the approved stance. It is interesting to reflect on the effect of film as the dominant cultural form and its effect on this.