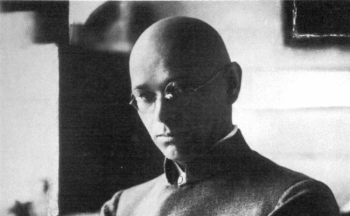

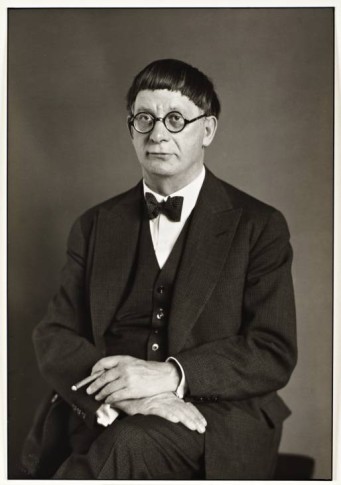

Hans Poelzig, architect and designer, Berlin Grosses Schaupielhaus

I find that often, on holiday breaks, my thoughts sort of meander over a lot of what I like. And I find myself thinking about the Bauhaus a good deal this year. The influence of the Bauhaus is probably greater even than the prevailing understanding suggests, and that understanding suggests they were very influential, indeed. From architecture to furniture, to typography, and painting, and theatre, but perhaps most significantly, as the final expression of a very rarified German bourgeois sensibility and intelligence, but also one that encompesed a collective and communal belief in social change. Now, there has also been, predictably, a backlash over the last decade. And that backlash is bothersome because it so misreads and misinterprets Bauhaus aesthetics and legacy. The Bauhaus, lets remember, was in fact an actual institution. It was a school. And the founder, and first director, was a WW1 veteran, who recieved two Iron Crosses, Walter Gropius.

El Lissitzky

Ben Davis writes:

“In January 1919, a rebellion in Berlin, the “Spartacus Uprising,” ended with the murder of the left’s most popular speaker, Karl Liebknecht, and its most capable thinker, Rosa Luxemburg. In February, Freikorps troops used artillery and mass arrests to crush the workers movement in Bremen, on the northwest coast, and the Ruhr, in the west, then went into central Germany to liquidate various organs of popular power. In March, there was another upheaval in Berlin. In April, Bavaria declared itself an independent “Soviet Republic” under workers rule, and was violently put down (becoming subsequently the cradle of Nazism).”

It is important to see the climate of that time in Germany. And to see the impulse for Gropius to issue his school manifesto in 1919.

Davis again:

“Gropius’ call to students is not an explicitly political document, but read in context it echoes with the utopian hopes of the era. The Bauhaus’ founding appeal is not the clarion call to industrial design that one might expect, given the school’s legacy — just the opposite, in fact: It denounces “designers and decorators,” and declares “Art is not a profession.”

Gropius himself wrote; “Let us create a new guild of craftsmen, without the class distinctions that raise an arrogant barrier between craftsman and artist.”

The Black Cat, dr. Edgar J. Ulmer, 1934

The current negative readings of the Bauhaus are fueled by a fear of Marxism, and more significantly, a fear of a school where the faculty was decidedly uncredentialed. Gropius sought out people he liked and respected; Joseph Albers, Herbert Bayer, Marianne Brandt, Johannes Itten, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Oskar Schlemmer, Lothar Schreyer, Gunta Stolzl. It is an extraordinary assembly of talent. The current snide and patronizing catelogue prose of Hal Foster (for the MOMA show, in I think 2009) suggests that the pedagogy was naive and mush brained, was akin to a hippie drum circle in Haight Ashbury circa 69. Now, on a personal level, when I think of my years at the Padua Hills Playwrights Festival and Workshop, which began in 1980 as I recall, and continued in its prime for about seven more years, before a gradual decline) I suspect the vibe was a lot like the early Bauhaus. Admittedly in a minor key. But then Los Angeles in the 1980s was not Germany prior to WW2. But more on that below. My point is that the sense of experiment and freedom is something 21st century academics like Foster will flee from in fear. Tut Schlemmer, a student at the Bauhaus, remembers… “No collars or stockings were worn, which was shocking and extravagant then. The students played in clamorous, experimental bands. They created lantern festivals and parades for which they crafted exquisitely impractical art kites. In general, they scandalized the population of provincial Weimar.” This sounds a good deal like Padua to be honest. But it also sounds a lot like a number of other experiments in education. The fact that Gropius was a pragmatist, with a hard edged aesthetic inclination, is only more evidence of the Utopian energy at work in those first years. And the communal socialist sensibility of the school. Remember also that Albers went on to help form Black Mountain College, and Gropius ended up at Harvard.

But today’s critics tend toward this, from K. Michael Hays:

“… we have become suspicious of the totalizing tendencies that see linkages between such unlike things as traffic signs, paintings, buildings, and bodies. Our items are not linked across groups and classes, but rather exist as purely nominalist confirmations of individuality and private property: This is so me, so this is so mine.

Were an ontology of today’s design possible, it would not be of a unifying technology or of an underlying, totalizing formal structure. It would have to be an ontology of the atmospheric – of the only vaguely defined, the nebulously articulated, and indeed the barely perceptible, which is nevertheless everywhere immediately present.” Now Hays isn’t, I don’t think, writing a parody here. And Hays teaches architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. These are sentiments and quasi ideas that I think would be welcomed at most major Universities in the U.S. It is the erasing of dialectics for one thing, but it is worse, it is a sort of purposely vague elitist jargon, and it somehow feels as if it would fit seemlessly into much of what passes for critical discourse today.

The Bauhaus Band, 1928

I am putting up links to a variety of things related to the Bauhaus. For it is crucial to understand that this was political art, and it was anchored in real praxis. And Gropius was clear that the totality of life was meant to be treated asethetically, and that all of aesthetics was to be a living part of life. It was also idealist, and unafraid of the mystical implications of art, and of the deeper structures of aesthetic thinking.

http://www.apartmenttherapy.com/the-frankfurt-kitchen-small-sp-113421

http://venetianred.net/tag/benita-otte/

http://chrisplosaj.com/bauhaus/

These are just sort of random samples. But they point toward the diversity of subjects and approaches that Gropius encouraged. Now, I’m not here to write a short history of the Bauhaus, but rather to try to suggest the sensibility at work, and to point to the reactionary aspects of so much of today’s critical community, especially regards art and culture.

Joahnnes Itten

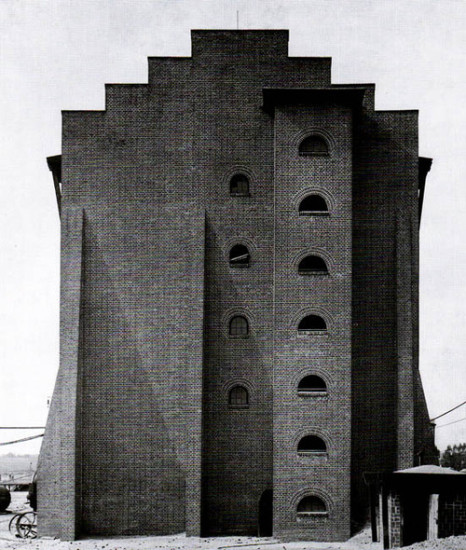

Here is Poelzig, from his essay Fermentation in Architecture:

“Every real tectonic constructional form has an absolute nucleus, to which the decorative embellishment, which within certain limits is changeable, lends a varying charm. First, however, the absolute element has to be found, even if as yet in an imperfect, rough form.

And the artist who approaches the design of structural elements solely from the viewpoint of external, decorative considerations distracts attention from the discovery of the pure nuclear form.”

Poelzig later designed sets for films, including The Black Cat, directed by Edgar J. Ulmer (not to be confused with the later Val Lewton film in the forties).

Socks Media Art Architecture has a great essay and many photos of the Lublin Acid Factory designed by Poelzig:

http://socks-studio.com/2013/11/26/hans-poelzigs-sulphuric-acid-factory-in-luban-poland-1911-1912/

Hans Poelzig, photo by August Sander

There is something profoundly haunting, too, in much undesigned architecture, the now destroyed Kowloon walled city (in Greg Girard’s remarkable photos) for example, and in the imaginary, such as the drawings of Piranesi. Or the photos of Michael Wolf of modern Hong Kong, or those of the abandoned city of Priyap, site of the Chernobyl catastrophe. In all of these the sense of destruction merges with a kind of palpable feeling of the terminal. The photos of Trevor Paglen, of secret U.S. military bases, or the work of Jane and Mary Wilson, in particular their photos of the former building that housed the East German Secret Police. This is, of course linked to our attraction to ruins, and Benjamin’s writings on the subject. But for a moment I want to return to the Bauhaus.

Arthur Dove

I think my attraction to the Bauhaus, besides the obvious excellence and lasting significance of their works, is the ideology embedded in everything they did. So, if we see in Russian Constructivists, and then in much Expressionist architecture, some of the roots of what Gropius distilled down, it is useful to also see the less obvious strains of influence. This was the cross pollinating of mediums and national tastes, of folk cultures eroding, or evolving through various avant gardes. Everyone from Dostoyevsky to Holderin, from Gottfreid Benn to Lautremont. Kafka to Van Gogh and Goya and El Greco. Still, the waning of modernism over the last forty years, say, has allowed for the inevitable eating of the Gods. It is not hard to feel a certain ennui when looking at Mathias Grunwald, and then Munch, and reading Kafka, and then to arrive at Warhol, and finally Jeff Koons. The death of a certain cult of genius, of ownership as authorship, was destined to crumble and one lives among the ruins of these artifacts today. But the promise of the Russian Revolution, and the complexities of Spartacus politics, the brutal crushing of the Bavarian Soviet Republic, was part of the climate against which Gropius and the Bauhaus was formed.

Thomas Hart Benton, self portrait

One senses not just the idealism, the socialist flavor of the pedagogy, but a certain almost paradoxical sensuality. I say paradoxical because so much of today’s received wisdom on Bauhaus work is that it lacks emotion, it is essentialist and dry and functionalist. Gropius was in a sense the most functionalist and pragmatic of all the Bauhaus faculty. And yet, even in Gropius’ work, at least during these years, one can see the sense of mystery and respect for the unknown forces of creation. What srikes me now, when I look at the whole body of work and thought that came out of those fourteen years is the tendency toward elimination of fluff and decoration, but the elimination of fluff and decoration in the service of finding some core beauty and purpose in artworks and design. These are purpose driven, but never at the expense of a transcendent sublimity. The purpose is not ideological, but humanist. It is the essential paradox, perhaps, of the Bauhaus. Since architecture looms in this posting, it is worth looking at that brief window in Weimar, and what happened to Bauhaus theory when it arrived in North America. The mysticism of the Bauhaus; especially in Kandinsky and Itten was still always devoutly rational. In architecture the rationality ….when you look at the work today…seems to follow the sense of the metaphysical.

Lipstick Bldg. Philip Johnson architect

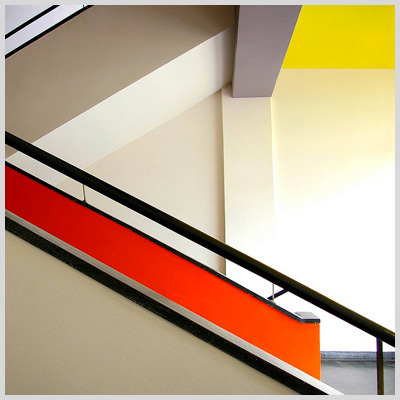

The flat roofs, the modular units, the smooth facades in mostly white, but also grey, and beige. The restrained use of primary colors red, yellow, blue and on occasional swatches of black. The Bauhaus was connected to social purpose, and utopian ideas of living space. The International style in the U.S. was quickly subsumed by Capitalism. Buildings in defacto honor of accumulation (The famous Seagrams Building in NY by Mies van Der Rohe and Philip Johnson). There was a strange quasi counter vibe in the U.S., I think mostly coming off the praires, and out of the West, the deserts and Rocky Mountains, and it was a masculinist gunfighter sensibility. In painting it was Thomas Hart Benton, and it became twenty years later Jackson Pollock and it was Charles Scheeler and even Georgia O’Keefe (the non masculinist version, but I’m inventing this notion, so whatever). This was also Edward Hopper and it was writing like Dreiser (midwest) and William Carlos Williams (east). And it was linked to that east coast WASP modernism, Charles Ives and Hart Crane. These are diverse artists but they are connected. And in a sense they connect to the German marxists and Freudians, and to the Bauhaus. But that connection was mediated by American Puritanism. The look of Bauhaus archtecture, the work of expressionists like Poelzig, and the Constructivists, all share an emotional bond. So the split in a sense comes when Bauhaus design and building travelled to the U.S. The rise of Philip Johnson is maybe most emblematic. Suddenly the structures look and feel elitist. The warmth is gone, but more, the utopian spirit is gone. Now Johnson came out of a different prairie, the midwestern Ohio urban world of 1906. But Johnson was always a mandarin in some sense. Descended from Hugenots, a boy who went to Tarrytown prep, and later Harvard, Johnson’s vision was always the vision of those who look down from above. If you compare the Bauhaus embrace of proletarian life with the propriator class vision of Johnson, there are striking comparisons.

Now, in the U.S. there were already clear modernist principles at work in architects like Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright by 1905. There are various ways to view the evolution of modernist architecture. Hermann Muthesius, in Munich, was drawing lessons from English Arts & Crafts designers, and this later influenced almost all early 20th century building (via Muthesius’ Werkbund), and so it’s very hard to trace isolated lines of influence because all of it was being seen and discussed by everyone. There was the influence of De Stijl in the Netherlands, Brick Expressionism, and so on. But back to the U.S., and the rise of a feeling in architectural schools following the first world war. In a sense, the big three of Gropius, Van De Rohe, and Le Courbusier came to define the shorthand for modernism in architecture. In the U.S. there was Wright and Sullivan and then Johnson. And the feeling in the U.S. never contained that socialist dream element. Even Gropius’ later work at Harvard feels closer to Johnson than it does to his early work.

Charles Sheeler

But since I’m not an architect, I will try to steer this back to what I hope my point is. And my point is about pedagogy as much as it is about anything else. The egalitarian tastes and vision of the Bauhaus was on an emotional level more connected to German Expressionism than to anything else. Le Coubusier in his way embraced an anti hierarchal philoposphy of construction as well, and drew on Gropius, but somehow the results felt different. But the Bauhaus was a school. It was one that taught painting and designed furniture and typography (and there is an entire essay yet to be written about the politics of font) and always worked things outward from a philosophical base, even as that philosophy looked to work down, stripping away the unnecessary. So, with the withering away of modernist aesthetics, has come an almost violent convergence of advanced capital and its marketing and branding artery, and with the academic left post modernists who mostly seem driven by insular and circular debates couched in an imcomprehensivel secret jargon known only by the high priests. Anything modernist is usually called out for Eurocentrism and whiteness. All these correctives were needed, it should be made clear. But, a good deal of socialist vision is being tossed out in the process. And there is a knee jerk reaction, at this point anyway, to a lot of, what is described as, hyper masculine art and writing. For these reasons I return to the Bauhaus. And to ask how one is to evaluate them at this point? And my answer lies in the, for lack of a better word, the sensibility of the school. The sense of the inmates having taken over the asylum. These were artists, by nature, and what came out of the school never felt as if it were being marketed (even if a lot was), or somehow the work of or by the privileged classes. It also, today, feels as it all has substance. I cannot find another word for it. It is clean, and functional, yes, and it is experimental, but above it all is the sense of aesthetic purpose, of teaching, and at the core, a primary substance.

Acid Factory, Lublin. Hans Poelzig, architect

The school disbanded under Nazi threat and when Gropius and others came to the U.S. the term International Style was coined (off a book by Johnson and Hitchcock in 1932, along with an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in NYC). But this was no longer the Bauhaus. The buildings were larger and deader and the pov was that of the elevated classes. Still, as I say, it is worth looking at these counter currents emerging in the U.S. Painters like Sheeler, who remains wildly underrated I think, and in literature, too. I wrote before of Dreiser, but Hart Crane was another midwesterner, who moved to New York. His work sort of straddles classes, though he, like Johnson, came from affluence. But not wealth. In a sense this is the story of Wallace Stevens as well. But the work was still rigorous and seems now, when I read it, to live within a tension between privilege and privation. But it was all serious work. It was work that lived in a time before hyperbranding and mass media, before the culture industry. Pollock was from Wyoming, and Clifford Styll in North Dakota, Motherwell in Washington state, and Rauschenberg in Port Arthur Texas. But while many I list are not midwesterners, they encompass something, a non urban sense of space, and these eastward moving artists ran into the immigrant Jewish (usually) artists in New York. This is what I miss now with the demise of modernism. The regional influences, the anti-institutional avant gardes, and the anarchic spirit of refusal. The anti authoritarian impulse that is seen in all Bauhaus work, and in the best of modern art when it emerged in the U.S. The refugee exile, the austere squinting gaze of prairie dwellers, and the flinty weatherbeaten psyches of the far West…these all percolated in various ways, and all of it today feels strangely exotic, almost. This is Christmas 2013, and the cultural landscape is strip mined by a ruthless ownership class, a vast military and an increasing desire for the propriators to finally solve their surplus population problem through wholesale violence.

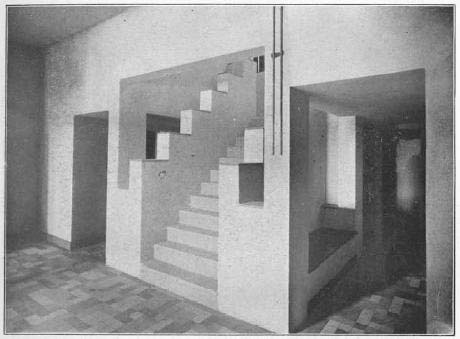

Stairs, Bauhaus school

The culture industry has so blanketed consciousness today that an educated 20% actually debate Orange is the New Black as if its Moliere, and have deep theoretical discussions about the philosophy of Vince Gilligan and David Kelly. Meanwhile drones are launched on Christmas day, and poor people die. Israel sends misiles and kill a 3 year old girl. And Salinas California, a small nowhere town in central California is proud owner of a jillion dollar military vehicle which its police department can use to, I don’t know, bust illegal parkers. And interestingly the photo of the Salinas police dept, in front of their new toy, shows the officers in camo uniforms. I guess the better to stay hidden amid the suburban shrubbery. There is in mass culture now an overt racism, and on the streets of the U.S. that racism is expressed in an ever escalating war on the poor, and primarely on the black poor. So whatever the shortcomings of much modernism, especially if we speak of the pre WW2, the cultural radicalism of a school like the Bauhaus seems utterly impossible today. I know of liberal colleges, and a handful of very good professors, but none are even close in spirit to the socialist and revolutionary spirit of the early 20th century. I write all the time about culture being the final bastion to keep barbarism at bay. Well, there is no culture now. And we have barbarism.

National Assembly, Dhaka. Louis Kahn, architect

There are always going to be outliers. I suspect Louis Kahn is one of them, in terms of architecture. When the call went out for scary architecture, Kahn’s government complex in Bangladesh was on the first list. Kahn is not really an international school architect. He is not really anything. I happen to love Kahn, and I think the death instinct I mentioned above is very clear in Kahn. It is why both the Salk Institute in California, and the Government complex in Dhaka resonate the way they do. One because it is this majisterial and grandiose set of structures in the midst of a nation of extreme poverty, and the other because at a medical research institute, the naked leering concrete death’s head of a series of structures seems at the very least sort of ironic. Kahn was born into an impoverished Jewish family in what is now Estonia. The exile again, the thousand mile stare of the immigrant poor, and the inate confidence, arrogance and narcissism of those who will themselves to the grandiose. Architecture Review called Kahn a ‘sentinal of principle’. He is often decribed in ways that seem a bit clumsy because authors reach for something impossible when trying to define Kahn. He had gravitas, but he had more, a strange almost uncanny quality that escapes you when first viewing his buildings. The scale is always huge and yet precise, and perhaps more than any other architect of the last century, Kahn created ritualistic space. He created theatres of cosmic scale. He created stages. There is an off stage with Kahn, and when you look at the monumental scope of the Dhaka complex, there is something frightening in it.

I find myself starting with the anarchic pedagogy, and aesthetic pragmatism of the Bauhaus, and arriving at the philosophical mystical pedagogy of Louis Kahn. The sense I have of modernism in the U.S. is fused with the constant awareness of teachers, of influence (even of the anxiety of influence). For Gropius knew the Constructivists and he knew German Expressionism. And Philip Johnson knew Van Die Rohe and Gropius, and Jackson Pollock studied with Thomas Hart Benton, and Robert Motherwell was in contact at Harvard with Alfred North Whitehead, and Philip Johnson studied the pre-Socratics while at Harvard, and Motherwell, with Bauhaus faculty member Joseph Albers taught at Black Mountain College, with Ilya Bolotowski, and Robert Duncan, and Franz Kline. There is extraordinary cross fertilizing here. And this was possible in an age much freer from cynicism. The left today cannot or will not allow itself a submission to mentoring. If Beckett was a secretary for Joyce, and if Marcuse took classes with Heidegger, there are all sorts of questions that arise. And they are fascinating, and they have importance. But what was lost, was the communal anarchy of that post Bolshevik Revolution moment. The Bauhaus was part of that. By the time Black Mountain came, this had waned. There was aeshtetic radicalism of a sort. But this was already a school for kids with access, with privilege, with connections. I love much of that work, but I find myself recoiling a bit too.

Rodchenko poster for Leningrad Department of Gosizdat (State Publishing House), 1924

So, pedagogy and politics. Aesthetic resistance. Creely taught at Berkely, and Marcuse in San Diego, and Olson was there, too, for a while. People will talk about Duncan and Olson talking for nine hours straight. R.D, Laing was being read, and Angela Davis was meeting with Marcuse about women’s rights in the revolution, and Creely had studied at Black Mountain, and everyone read Roethke, and Zukovsky apparently never spoke. One can go on and on like a parlour game, finding the connections. Knowing your teachers, knowing influences is important. Who did Louis Kahn study with? In a speech in 1971 Kahn said:

“The room is the beginning of architecture. It is the place of the mind. You in the room with its dimensions, its structure, its light respond to its character, its spiritual aura, recognizing that whatever the human proposes and makes becomes a life.”

Kahn studied at the University of Pennsylvania, but Kahn found his vision late. He was in his fifties, after a stay at the American Academy in Rome. His visits to Egypt, to India, and Greece were really the trigger for his mature vision. But Kahn is hard to write about. Perhaps out of everyone mentioned in this long holiday posting, Kahn is the most enigmatic.

Brian Ulrich

In this era of resurrgent racism, and of the attention economy, and of the surveillance state, the U.S. has taken a final (?) sharp turn to the right, to the creation of a new feudalism. People are prevented from growing their own food, and the medical profession is implicated in the chemical warehousing of a full quarter of the population. Research studies are bogus, are bought and paid for and what was left of an already threadbare safety net has been totally shut down. No more food stamps, no more unemployment benefits, and only prison looms as a growth industry. Two million people are in custody today, more, far more, than any other country in the world. And the US government spends ever more on propaganda: from close cooperation with Hollywood, to the constant construction of movie like publicity narratives (Pussy Riot comes to mind), and the left seems more and more to be a culture of self loathing (witness the latest campaign to discredit Glenn Greenwald and by extension Edward Snowden). In the end, the U.S. public mostly doesn’t care about the Snowden info. Everyone knows social media is complicit with the NSA and Homeland Security. And yet, what is one to do? CCTV watches daily life 24 hours a day. Whatever passes for the commons is now a laboritory in control. So, given this landscape, it feels useful to contemplate the buildings we live and work and shop in, and to examine the feelings of power implied in architectural grammer now, not to mention in the compulsive repetition of kistch on TV and in movie theatres. And, perhaps most of all, to examine the destruction of institutional education.

William Lescaze, interior Norman House, NYC

I can imagine artists collectives, but Im not sure I can imagine the seriousness of a Bauhaus. I think the rise of a kitsch culture, of a hyperbranded entertainment aesthetic, of a disposible culture of distraction, and of an indifference or even hostility to the humaness and utopian ethos of a school such as the Bauhaus makes the creation of this sort of spirit in a school almost impossible. The psyche under advanced capital is permeated by fear. The adjustment today, which is abstract, is to a landscape that is itself only another abstraction. It is populated by simulacra, and by brands, not material life. This is among the deepest contradictions of this new feudal society, which depicts itself, via the culture industry, as stable and moral and rational. Above all else as rational and reasonable. And anything; racism, violence, misogny, and inequality is readjusted to be experienced as normal and natural. The bombing by remote controlled drones of a wedding party garners no more attention than the latest fashion trend. The society provides narratives of emptiness, of distraction, and narratives without conclusions. It is all just a steady stream of ‘now’, in which fungible parts and characters act out pointless and solipsistic behavior that either ends in non resolution, (depicted as resolved), or simply stops. The landscape that people live in is one of emotionally fatiguing oppression. It is unfriendly to the human.

Al Held

When I hear shrinks or philosophers talk about love and anger, I always feel slightly uncertain as to what they mean. Is our rage really about the lack of love from parents, or the fact we had to barter our truer natures to get that love? Or is it as Freud imagined, an instinct toward destruction. I am not at all sure these days because I am not sure anymore if even our primary object of desire, our primal link to the mother is even as decisive as it once was, so truncated is consciousness now. When I ponder a school, a new Bauhaus, I am able to come up with an ideal faculty, in my head. It is much harder to imagine students. I’ve had brilliant gifted students over the last ten or fifteen years, but with only a couple exceptions would they do anything to veer off their career path. The fear of not having a career is almost a metaphysical core terror. There are certainly utopian dreams among students I meet, but it is mediated. The degrading of language plays a role in this, no doubt, as does the conditioning of mass culture, of corporate media, and the sort of endless bombarding of image, and not just image, but of particular kinds of image. The sense I get is that increasingly the young have started to ‘see’ the world with black outlines around the image — in other words, the way advertisements treat image. They are manipulated images. And people now manipulate FOR themselves. Its sensory auto-manipulation. Its a sort of pre-emptive manipulation. This is a direct relationship with Debord’s generalized autism. The world is barely a movie anymore, it’s close to a cartoon. A digital live action short, a video game. In one way, the world, nature, falls short. But the hostility of manipulation, on all ends of the dynamic, is related to the fear and aggression that is so knotted in the post modern psyche.

J.J.P. Oud, architect, interior DeVonk bldg, Netherlands

Today’s darling in architecture is Joshua Prince-Ramus, a Yale grad, former collegue of Rem Koolhaas, and part of the creepy TED network. Prince-Ramus hasn’t really done enough for a final verdict, but it is hard not to have rather large misgivings. There is a glibness and facility to his work, but there is also an inherently superficial quality and a kind of smugness. Prince Ramus hits the right buttons, employs the approved tropes, and yet, when looking at the whole, it is always less than the sum of these approved parts. The interior spaces of his buildings feel corporate. There is an unconscious sort of pandering to those who judge architectural competitions, and maybe that is unavoidable. It is interesting, speaking of cross pollination, that the so called Big Five of New York architects in the 60s included Richard Meier and Michael Graves. Meier had once clerked I believe with Marcel Breuer, late of Bauhaus. Merier went on to become among the most paralyzingly boring of all late 20th century architects, culminating is his giant dental clinic on a hill, the Getty Museum in Los Angeles. Of that group it is Graves, though, who has had the most deliterious long term effect, and who has also aged the most poorly. When one wants to point to the self conscious kitsch end of the post modern architectural spectrum, one usually uses Graves as an example. From the Dolphin Resort at Disneyworld, to merchandise sold at Target stores, Graves is the Liberace of American architects…and thats probably hugely unfair to Liberace. This entire group, in a sense, grew in the shadow of Philip Johnson (though Peter Eisenman remains a sort of unique story, and his work retains a good deal more intrigue than any of the other four).

Buenos Aires, 2013

Wittgenstein’s sister called the house her brother designed for her, ‘a place better suited for Gods’. She said no human can live in it. I actually ordered the doorhandles Wittgenstein designed for that house, for the cabin my wife and I have in Norway. They are somehow majestic, and the same company sells Gropius designed handles, too. (http://www.bauhaus-fittings.com/)… (http://tmdtctv.blogspot.no/search/label/LUDWIG%20WITTGENSTEIN). The point is that while the handles are beautiful, and they are, it wouldn’t really matter if Wittgenstein designed them or not, for they are totems, and the create a ritual space ..even if it leads to my lumber shed. But to bring this back to Prince-Ramus and his self branded celebrity architecture; his buildings lack the spiritual lack of purpose…paradoxically…that some of DeStilj’s designers worked with, and certainly they fail in comparison to the Bauhuas, or even to, say, a number of Brazilian modernists (Niemeyer, Reidy, Costa, et al), or to these days, Frank Gehry. Say what you like about Gehry, he flaunts a kind of excess of vision (as did Kahn)and work such as Reidy’s Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janerio, or Gehry’s Bilbao Guggenheim makes Prince-Ramus seem banal.

The architecture of the future has to be the architecture of the people. Tiny house living, and obviously a plan of sustainable materials used in designs for sustainable small agriculture. Any quick google search using words like habitat and sustainable and renewable will lead one directly into the labyrinth of NGOs, and white Christian corporate funded first world agencies of “help”. There is nothing quite so creepy or icky feeling that reading through the “about us” section of any NGO web site. There is however good work out there. Interesting work. And its just done far outside the world of NGOs (that said, some, such as Prince Charley’s INTBAU are better than some others). But the point is that if one goes to the faculty page of almost any U.S. University for departments in Enviromental Design, or whatever they want to call it, one is going to see TOTALLY a faculty of professors and assistant professors with MA’s and PhD’s and double PhD’s, and I cannot help but find my skin crawling slightly. I am sure, I am, that there are good departments of design and architecture… but for the most part this is the world of white supremacist patronage and condescension. It has come to feel a good deal more cut off from human life, the life of the people, than such institutions did 60, 70, 80 or 100 years ago. Perhaps that is me indulging in nostalgia, I don’t know. Still, there are interesting projects, ideas, and people out there:

http://www.scidev.net/global/design/news/open-source-opens-up-architecture-for-the-poor.html

http://www.hassanfathy.webs.com/

Affonso Reidy, architect, Museum of Modern Art, Rio.

Under the totalitarian societies of the West, which really means primarely the U.S. and UK, the spirit of people is siphoned off, the human temperature is lowered until this 2 a.m. glazed Casino patron consciousness never leaves. Everything feels to be growing in fraudulence. That is my sense. People argue over increasingly petty things. Sectarian battles about fuck all nothing. Corporate news feeds people stories of no consequence, stories like pussy riot and duck dynasty. And hours are spent arguing about these things. Meanwhile the poor are terrorized more acutely, far more acutely, than even ten years ago. There is a growing faction of the left that insanely babbles the most puerile and reactionary jargon, while identifying themselves as socialists. Some call their readers ‘comrade’, and they all create cover for the most racist and white supremacist writing imagineable (Laurie Penny, cough…Bhaskar Sunkara…cough…Zizek….), stuff that wouldnt seem out of place in an op ed for the WSJ.

Interior, Glass Pavillion. Bruno Taut, architect 1914

From WSWS, a final Christmas thought:

“In the course of 2014, another 3.6 million workers will exhaust their state unemployment benefits and be left with nothing. Taking into account family members who rely on these benefits as their sole source of cash income, some 5 percent of the US population will face destitution as a result of the cutoff of these funds.

A renewal of the extended benefits was left out of the budget deal reached in Congress earlier this month, with the approval of the White House and congressional Democrats. The total cost of extended unemployment benefits would be $25 billion in 2014, less than 1 percent of overall federal spending.

The same Congress that allowed the jobless benefits to expire voted December 19 to authorize nearly $633 billion in military spending for 2014, money that will go toward funding the war in Afghanistan, overwhelmingly opposed by the American people, and Washington’s preparations for even more bloody military interventions.”

Zombie House. 2013 http://www.viralnova.com/zombie-house/

Ready for an airstrike.

John, thanks for this – another very interesting post that covers so much ground it’s hard to know where to begin – so I won’t! (New Year beckons. I wish you a good one.)

Louis Kahn’s Dhaka complex is amazing, and I had not been aware of it before this blogpost. (The images you post here are another great strength of this blog.)

Chris Hedges has a very powerful new post about a (play-)writing workshop he did recently with prisoners in New Jersey:

http://www.truthdig.com/report/item/the_plays_the_thing_20131215

for more “profoundly haunting” images of structures, I just came across http://prisonmap.com — as you view the images, the surreal and all-too-real qualities seem to alternate.

thanks patrick. Yeah, that Dhaka compound is just breathtaking in a way. And George, thanks for that. Amazing. Just amazing. 2