There are two things I want to write about this entry. One has to do with Sianne Ngai’s book Ugly Feelings. The other (which is directly related) is how much Herman Melville seems to coming up in public discourse. I can think of three separate mentions of Melville in Op Ed pieces, and Chris Hedges wrote a nice piece here using Moby Dick…

http://readersupportednews.org/opinion2/277-75/18315-we-are-all-aboard-the-pequod

Ngai’s book brings up two other of Melville’s works, Bartelby The Scrivner, and The Confidence Man.

It is probably not at all a coincidence that Melville is being resurrected, besides that fact he is the greatest writer the US has produced, he is also among the Biblically oracular and one linked in his vision, directly, to the venal and vicious American project of conquest and expansion.

Ahab is a figure that is quintessentially American, and echos down through Ethan in The Searchers to Judge Holden in Blood Meridian to Alonzo in Training Day. He is the voice of the genocidal Indian Killer, of the scalp collector, of the whaler and the buffalo killer, and even in Alonzo, the collaborationist working for the ‘Man’, the profiteer in violence: but in Ahab there is knowledge, too, and in Ethan and even in Alonzo. The psychopathic insight into the tragic condition.

Somehow these figures have devolved to simply the bureaucrats of violence, the murderous painter of white fluffy puppies, or just the urbane lawyer with the dead eyes of the reptile. It is also General Petreaus, or Admiral ‘Rat’ Willard, or its Bernie Kerik, or Rahm Emanuel, or it’s David Koch or Tim Geithner.

And this reminded me of Virno’s “sentiments of disenchantment”, which then came up in the book I was reading, by Sianne Ngai. I dont find the “Ugly Feelings” book totally convincing, though still highly valuable, and in fact the basic problem leads back to what Virno was trying to express, and which I think was misread. Virno saw certain skills developing, adaptively, under capital of the last thirty years:

“…the ability to keep pace with extremely rapid convergences, adaptability in every enterprise, flexibility in moving from one group of rules to a another, aptitude for both banal and omni-lateral linguistic interaction, command of the flow of information, and the ability to navigate among limited possible alternative.”

There are several threads in play, here. One is the loss of traditional learning, of both intellectual practice and simply trades and artisanal knowledge, as well as just organized community awareness related to industrial jobs. The new skills come from one’s pre-labor life in a sense, the prolonged marketed “adolescence” of western society now. This is a huge demographic for Madison Avenue. This artificially prolonged “youth” breeds a sort of flat-lining of expectation and surprise. The emotions of second generation learning (electronic media, social networking, etc) lacking in core foundational experience, are replaced with highly adaptive and fungible skills. Way back Benjamin said something to the effect that we have no real experiences anymore. This is as good an explanation for the the rise in opportunism and cynicism as I can think of. It is also perfectly fear driven.

Stephen Pokornowski writes:

“Virno points to cynicism’s limited receptivity to signals as forcing the vital context of emotion into formalisms and abstraction until they return simplified and unelaborated.”

This relates to what I have written about the autistic reduction in reading narrative — in film or TV as well as literature, really. The de-noising of the background. Its a making linear something more knotted originally. Spread it out in a semi-detached fashion. In one sense it is a superior adaptive strategy. Its schematic, rather than sensual.

This is the adaptive background to the new electronic mass society of the West. I see cynicism recycled in various forms on both the right and left. There is a strange de-sexualizing that goes on, too. Androgynous and affectless. This relates to what I experience even in reading a lot of “theory”, or lit-crit stuff. The private vocabularies and jargon aside, there is a sense of posturing, but also in lectures and live presentation a sort of intentional disheveled false modesty— it’s actually like a false modesty hiding a pretended erudition. Its sort of three layers of bullshit wrapped in one body.

But to bring this back to Ngai’s book for a second. Her quote of Adorno in the intro bears repeating…

“As Adorno’s analysis of the

historical origins of this aesthetic autonomy suggests, the separateness from “empirical society” which art gains as a consequence of the bourgeois revolution ironically coincides with its growing

awareness of its inability to significantly change that society—a

powerlessness that then becomes the privileged object of the newly

autonomous art’s “guilty” self-reflection.”

Ngai then suggests this question of emotions and art can be traced back to Aristotle and his notions of catharis vis a vis Tragic drama. I have always felt that Aristotle was largely misread. Or at least over simplified. And certainly if one reads Heidegger on early Greek thought (pre Socratics) it is easy to feel the later Oxford reductions at work. Aristotle’s notion of a cathartic purging, and of tragedy drawing out feelings of fear and pity, is a very simplistic reading. For Greek tragedy was specifically built upon the cusp of a migrating from the daimonic irrational of the pagan Gods, to the rationalist and civic life of Athens at the time. The fear wasn’t a fear that comes to us from watching a horror film. Nor was it the fear of terrorists brought to us by the U.S. state dept. Nor was it the fear of jumping off the highest platform into a waiting pool below.

There are qualities of fear. And there are qualities of pity. And there are qualities of what is meant by purging. And what does that mean? Purging. Well, without getting into an entire analysis of Aristotle (though that might be worth doing at some point) the fact remains that terms like purging, and wonder and catharsis are highly qualified in a sense. As is the word *pleasure*. In the case of wonder (rhaumaston) the real core is mystery, and a mystery that there is no desire to solve, but a mystery that is really a sense of awe at our mortality, and…perhaps as importantly, an awe at what is being missed and has been missed, and for which we strive to reclaim some tiny glimpse or foothold from which we can reflect (mimetically) on this uncanny sense of loss. This is almost always left out of dry academic readings of Aristotle. So, purging is the elimination of chatter and mental debris and noise (and again, I think that the autistic quality of reading information is linked here). The sense of wonder as it happened in the event, the presenting of Tragic drama has been distorted by European (Anglo mostly) cultural readers steeped in an Enlightenment set of values and principles that instrumentally examine the world as something to conquer. In one sense this is the western Imperialist reading of Tragedy, and of catharsis and wonder. And of art in general, perhaps. Walter Benjamin saw that once the ritual, the mythic irrational was removed (the Dionysian, the aura) that something secular and usually fascist replaced it, and art was political. Frank Kermode wrote…

“Certainly, it seems, there must, even when we have achieved a modern degree of clerical scepticism, be some submission to the fictive patterns. For one thing, a systematic submission of this kind is almost another way of describing what we call ‘form.’ ‘An inter-connexion of parts all mutually implied’; a duration (rather than a space) organizing the moment in terms of the end, giving meaning to the interval between tick and tock because we humanly do not want it to be an indeterminate interval between the tick of birth and the tock of death. That is a way of speaking in temporal terms of literary form. One thinks again of the Bible: of a beginning and an end (denied by the physicist Aristotle to the world) but humanly acceptable (and allowed by him to plots).”

Ngai’s book is an interesting look at what she describes as

“this book turns to ugly feelings to expand and

transform the category of “aesthetic emotions,” or feelings unique

to our encounters with artworks—a concept whose oldest and best known example is Aristotle’s discussion of catharsis in Poetics. Yet this particular aesthetic emotion, the arousal and eventual purgation of pity and fear made possible by the genre of tragic drama, actually serves as a useful foil for the studies that follow. For in

keeping with the spirit of a book in which minor and generally

unprestigious feelings are deliberately favored over grander passions like anger and fear (cornerstones of the philosophical discourse of emotions, from Aristotle to the present), as well as over

potentially ennobling or morally beatific states like sympathy, melancholia, and shame (the emotions given the most attention in literary criticism’s recent turn to ethics), the feelings I examine here are

explicitly amoral and noncathartic, offering no satisfactions of virtue, however oblique, nor any therapeutic or purifying release…”

However, it is still premised on what I contest is a mis-reading of Aristotle and of Greek Tragic Drama. But…the point I want touch on is the way in which this connects with Virno’s ideas about our mediated leisure time, and the way in which advanced Capital today has privileged certain impairments as actually very practical adjustments to the irrationality of modern life in the West.

Modern productions of Greek Tragedy are almost all uniformly terrible. Why is that? I suspect because they are simply reproducing a schematic reading of English classicists interpretation of Aristotle and Sophocles (and really, of Shakespeare, as well). The tragic, for Benjamin and for Adorno, was to make present something, in the event, on stage, to unmask something which daily life and which the new ordering of life was keeping hidden. And it was the irrational myths of pagen Gods, it was the utterances of the oracle at Delphi, and for Benjamin the ‘mourning’ play of the 17th century in Germany was the secularizing of time — temporality, extending it in linear fashion, logically, and scientifically in a sense. The loss was the coiled mythos of Greek drama. Catharsis isn’t the purging of pity and fear as if we were watching Halloween 6, it is the waiting chill and shudder of fleeing Gods, the sense of complicity in the declarations of the oracle. And Greek drama was declamatory. It was not psychological. It spoke and as speech it was tragic, for time turned on itself. From cult to museum exhibit. Dionysian energy of release, not the categorizing of Enlightenment science. It is easy to turn this into some mush brained new age love-in, or rave, or a swinger’s party — it was the cold stone psychic floor of mortality…

“The authenticity of a thing is the essence of all that is transmissible from its beginning, ranging from its substantive duration to its testimony to the history which it has experienced. Since the historical testimony rests on the authenticity, the former, too, is jeopardized by reproduction when substantive duration ceases to matter. And what is really jeopardized when the historical testimony is affected is the authority of the object.”

Benjamin

If Virno is at all right, then the elevation of opportunism and opportunistic adjustments in feeling and ethics, and the attendant cynicism that is both cause and effect, have rendered the Enlightenment/Colonial translations dead. Tragedy cannot be commodified, literally.

My sense of the West today is that fear casts a shadow over almost everything, over all human experience. It is a marketed fear. And possibly it is often, at least in part, a form of anxiety. If this extended adolescence provides time to develop certain skills — skills born of the impermanence of one’s working life, the loss of traditional community learning, and connectedness, then the emotions experienced in our encounters with artworks are going to be mediated by the encouragement toward infantilized emotions and a pre-packaged template of childish feeling and desire.

Benjamin said of the destructive (fascist) character; .”…sees nothing permanent. But for this reason he sees ways everywhere…. What exists he reduces to rubble, not for the sake of rubble, but for that of the way leading through it.”

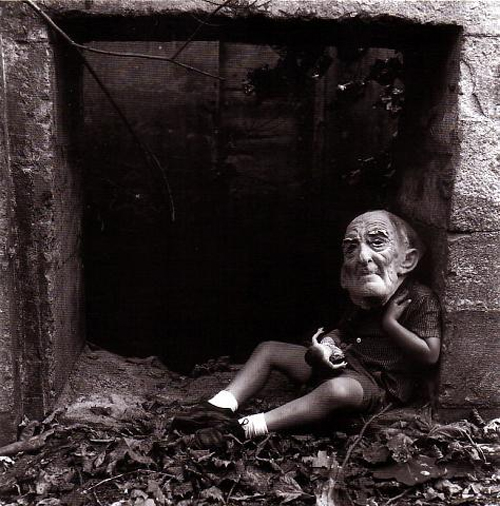

We have no tragedy because we, for the most part, have eradicated the potential for deep feeling. It is fan culture, and increasingly a culture in which our encounters with cultural material is apriori trivialized. The trivial is marketed as something positive (though under other names, such as entertainment or fun, and a host of sub-categories like *popcorn movie*, or heartwarming, etc). Ngai is certainly correct when she raises the topic of categories such as zany and cute, and her astute understanding of Capital and its interaction with all cultural products…and the recognition, with Virno, that this signals a shift in perspective caused by shifts in financialized Capital and the state’s logic of social domination. Still, when she describes “cute” as an aesthetisized powerlessness, I’m not sure I totally agree. Cute is often an aesthetic AND psychological strategy to wrest power by an exhibition of timidity and shyness. But that exhibition is also the cloaking of itself, the creation of a fixed mask of cuteness. It hides more than it reveals. It also the deceit that says, I cannot do that, I am weak or passive or shy or sensitive, and you must do it for me. There is a gendered element in this, as well. The relationship between cute and sexual objectification seems complex and worth analysis. Cute is also almost always sentimental and the sentimental is always sadistic. George Bush paints cute and sentimental white fluffy puppies.

In the shadow of NSA spying, and open flaunting and normalizing of government impunity, I think Ngai has touched on something important in her understanding of what anxiety has come to mean in aesthetic terms. One of the hallmarks of Hollywood film and TV today is the removal of ambiguity. There is a simple appeal to a formulaic cause and effect that allows for a “explanation” for “why” someone did what they did. The paradox here is that these formulas are only at work in aesthetic realms. The state propaganda is almost the exact opposite in which motivation is always opaque. “Why do they hate us?”. Well, because they are NOT us. They are “other” than us. In popular culture this is usually expressed in quasi religious terms like “evil”. The terrorists (usually not fully identified) are simply ‘bad’ and their humanity is de-emphasized, and strictly speaking they are barely even human at all. This is classic propaganda, and something Goebbels knew well. So, in popular studio film, the villains, if connected to terror or politics somehow, are unfathomable. Otherwise, the explanation is usually a pop-psychological one. However, there are certainly exceptions, and a show such as “Homeland” presents the ‘evil mastermind’ who is orchestrating the terror attacks as motivated, partly anyway, by revenge for the death of his son. But is this really an exception? I’m not sure, because that narrative device is rendered in clear unambiguous ways. And here a question is raised about how the *other* is represented. There is rarely any complexity of feeling in such characters. There is only the “explanation”. He is revenging his son’s death, AND he is *other*. The protagonist (or co protagonist) is torn by conflicting emotions and by guilt. And we are all guilty under Capital. And white people have a conscience, albeit one with with very strict parameters. The Muslim terrorist is driven by irrational (and unknowable) urges, much like an animal. The evil other, in fact, much like any underclass character, is simply reacting, their aggression is instinctual (if that) and hence no doubt need be exhibited in their extermination.

Ngai raises an important point, though, with “tone”:

“By “tone” I mean a literary or cultural artifact’s feeling tone: its

global or organizing affect, its general disposition or orientation toward its audience and the world. Hence, while the concept I refer

to includes the connotations of “attitude” brought to the term by

I. A. Richards and other New Critics, I am not referring to the

same “tone” they narrow down to “a known way of speaking” or a

dramatic style of address. Instead, I mean the formal aspect of a

literary work that makes it possible for critics to describe a text as,

say, “euphoric” or “melancholic,” and, what is much more important, the category that makes these affective values meaningful

with regard to how one understands the text as a totality within an

equally holistic matrix of social relations. It is worth noting here

that literary criticism’s increased attention to matters of emotion

has predominantly centered on the emotional effects of texts on

their readers, and, in the predominantly historicist field of nineteenth-century American studies, where the surge in the discussion

of emotion has seemed particularly intense, on the expressivist aesthetics of sympathy and sentimentality in particular. But what gets left out in this prevailing emphasis on a reader’s sympathetic identification with the feelings of characters in a text is the simple but powerful question of “objectified emotion,” or unfelt but perceived

feeling, that presents itself most forcefully in the aesthetic concept

introduction of tone. The absence of attention to this way of talking about feelings and literature not only is specific to recent literary scholarship on emotion (though it becomes particularly glaring in such a context), but points to a long-standing problem in philosophical aesthetics that we have already had a glimpse of above, in which an

overemphasis on feelings in terms of purely subjective or personal

experience turns artworks into “containers for the psychology of

the spectator” (Adorno, AT, 275)”

Tone has always been difficult to define (not that emotion and affect are not also, but not to the same degree, and where the question of location becomes more of the problem). But, tone is important exactly because it is so hard to define and isolate. There are class considerations of course, and to a slightly lesser degree ones of gender and race. This segues into Ngai’s analysis of Melville’s Confidence Man, and to a discussion of envy and resentment.

She quotes Jameson;

“the theory of ressentiment, wherever it appears, will always itself be the expression and

the production of ressentiment.””

This is very interesting if we start to look at popular studio film and TV today. In one sense Zombies, aliens, and other plagues on civilization are seen as disruptive and threatening, exactly as the criminal agitation of the underclass. And not just the underclass, but very specifically, often, women and minorities. One can see the obvious almost colonial mind set here, the natives upsetting the established order. Audiences are trained (lured, seduced even) to take the point of view of the producers of this product. Of mainstream entertainment. This is where envy enters again, sort of sideways.

Ngai again…

“For envy makes no claim whatsoever about

the moral superiority of the envier, or about the “goodness” of his

or her state of lacking something that the envied other is perceived

to have. Envy is in many ways a naked will to have. In fact, it is

through envy that a subject asserts the goodness and desirability of

precisely that which he or she does not have, and explicitly at the

cost of surrendering any claim to moral high-mindedness or superiority”

So envy and resentment. These are clear political PR tools of the last decade. The white male world is being disrupted. What is curious about envy, however, is that it often feels omni-directed. It is not envy for what Donald Trump has, it is envy for of everything “I” don’t have, which includes a stable hierarchy (white supremicism) of power and privilege. It is envy for what other deserving white men don’t have (that lured identification with the producer, the aggressor, the state machine of power). In aesthetic arenas, this envy is more as Ngai suggests, bereft of any moral superiority. But then that moral superiority is a given. There is much more to say here and Ngai’s book is usually very cogent in its examination of all this.

But back to ‘tone’ for a moment. What I sense in a good deal of non-studio film and in some prose (and almost no theatre) is the increase in a ‘narrative of dread’. It is almost as if the established *bad guys*, or *terrorists* or whatever are no longer sufficient to contain the feelings of fear in the corporate elite or in the directors they finance, and this sense of dread is a surplus emotion that is bleeding into the work. It is interesting to me that so little MFA writing is even worth using as examples in this, so inbred and solipsistic are the works. The dystopian landscape of shows such as Falling Skies, for example, is dramatically driven by a distrust of the alien allies, because they don’t share the same traditional (white male) values as the surviving rebel forces of mankind. That Speilberg is the producer should come as no surprise. It is a purely militarist narrative, a reconstruction drama, in which race and purity and societal stability are at stake with the alien invasion.

“The identically persistent self which arises in the abrogation of sacrifice immediately becomes an unyielding, rigidified sacrificial ritual that man celebrates upon himself by opposing his consciousness to the natural context”

Horkheimer & Adorno

Falling Skies, Dream Works TV, 2012

The authoritarian protagonist is one who must first have exercised a harsh regime of discipline (punishment) upon himself. He is a survivor. The survivor then has the moral right, earned, to dominate others as he dominated himself. The ‘tone’ of corporate film and TV is one in which the implied audience is already resentful. It is almost always, on one level, a narrative of scapegoating. Villains are external threats to the established hierarchy, and this even takes the form of independent “art” as a threat to institutional commodified culture. Taking orders coherently is the highest of virtues. The ‘tone’ is one not greatly different from the drill sergeant. In Falling Skies the single minded former army officer (Will Patton) is as much the moral center of the show as Noah Wylie’s *everyman* former school teacher (who learns military discipline from Patton). There are constant references to the American Revolution. Nostalgia meets militarism. There is a gendered subtext here, too, for women are seen as unable to learn that ruthless self denial and witholding of compassion that make for the effective soldier. It is only when certain “special” female characters DO so transform (Zero Dark Thirty, or Homeland..albeit in the latter the woman is bi-polar and in need of male assistance) do they graduate to key protagonist stature. You are either brutal or cute.

Words lose meaning, and are only orders. You must obey. Orders are robbed of subtext as language. When language is only orders and instruction manuals or technical blueprints, we are in the arena of the totalitarian. For the purposes of this post, I want to just add that tone, and what Adorno called the “mood” of the artwork is not independent from its production. The corporate system, the vast financial empire of media, that produces these narratives, is embedded in them in both tone and mood. The characters cannot exist outside of their system of toil and they relate only to the narrow enclosure of narrative purpose. The psychological or psychoanalytical attachments that the viewer forms are the real basis of the ideological system at work. The language is cleansed of ambiguity, and increasingly any relationship to intellectual pursuits is made an object of ridicule ( there is a scene in another dystopian sci fi show, Defiance, in which a young policeman/solider is reading Moby Dick, and when he quotes it, he is laughed at by his superior, a tough “no nonsense” career warrior). The landscape is always really the corridors of SONY or Paramount or HBO where white male power is firmly decreed, and where economic goals are ground zero for what really matters. Statistics, forensics, computational analysis, don’t lie. The bottom line. The corporate conference room is reproduced as the white house oval office, or Wall Street, or, as in Falling Skies, the new president’s makeshift private office. White male power is to be worshiped as something all must be willing to die for.

“The breeding ground of disobedience does not lie exclusively in the

social conflicts which express protest, but, and above all, in those

which express defection”

Virno

The exemplary Henry Giroux wrote recently…

“Why does the American public put up with a society in which “the top 1 percent of households owned 35.6 percent of net wealth (net worth) and a whopping 42.4 percent of net financial assets” in 2009, while many young people today represent the “new face of a national homeless population?”[7] American society is awash in a culture of civic illiteracy, cruelty and corruption.”

How does that happen? Well, one answer lies in the internalizing of the tone and affect of corporate mass media. One can listen to the demonizing of Edward Snowden on mainstream news and see how closely the very language reflects that heard on TV and film produced by corporate studios and networks. The “tone” is hugely important. The inspecting of aesthetic positions vis a vis cuteness, and envy and resentment, and of how they are meant to mean something in specific ways at specific times is very revealing. The lured audience desires and expects the casual friendly smile from its elected politicians, but today the confused tone, the innappropriate laugh (Hillary Clinton), the disjointed gestures (Bush Sr, Biden, and Kerry), or the sneering sadistic glee of Cheney or Bush Jr or (again) Hillary, has all become common. And this subaltern audience, the junior managerial clerks and assistants, the guys in cheap suits for the service sector, they are invested hugely now in the political theatre, and they were trained and conditioned for it while watching their favorite TV show or movie franchise. The normalizing of state criminality (de-facto forcing down of Morales’ plane by EU quisling states for example) or the valorizing of Israeli gangsterism and ethnic cleansing of Palestinians, and the language of vague PR speak from White House spokespeople, which is now even reflected in the posturing of much of the left (listen again to those SI videos from the previous post) and its own language which mirrors this same vague formless set of affects, the same ‘tone’ of infantilized sweetness, the kindergarten teacher explaining finger painting, of self promotion and cuteness. This childish “tone” of a Jodi Dean or the forced wit of China Mielville, like the seaside summer stand up begging for laughs, or the self promotion of almost everyone with a book, or an occasional guest spot for the Times, is part of a performance of neutralized dissent. When I hear Chavez repeatedly attacked in subtle ways, I know the left project in the English speaking West is in dire straights. When Mielville mentions Chavez hanging out with “unsavory” international characters I am speechless. Who might that be? Iran? China? Would that be the comment if he was meeting with David Cameron or Joe Biden or Merkel or Hollande?

The academic left rarely call this out for fear of job security I suspect, but it is practiced as collegial respect. The sense of seriousness is missing. Gravity need not be humorless, but it would be good if political dissent managed to avoid snark and self satisfaction, and worse, careerism.

Our individual social encounters emulate our aesthetic encounters, the tone of which is progressively like corporate TV shows and news. The ironic and sarcastic replace actual emotion, and that emotion now drifts ever further into reified corners of our hyper-branded existence, or simply goes missing.

http://creativetimereports.org/2013/06/25/surveillance-and-the-construction-of-a-terror-state/

i was thinking about these trivial emotions as manipulative – someone famous said something about a slight temptation being more difficult to resist than a great temptation because its doesn’t provoke a conscious contest. These trivial affects are easier to stimulate. But the most significant manipulative impact is shame – which lasts. Fear of shame is a lever of discipline especially now in this exposure culture.

contrast this to the emotions on display in ancient Greek drama…as I mentioned, I believe this stuff of remote and that the effects contemporary theatre arts professionals use them to create are impositions that don’t fit very well. But shame seems to be the one that remains accessible.

The Virno seems superficial to me – correct in description as far as that goes, but again, the absence of class paradigm is striking. “We”, everyone is a bourgeois culture producer with some capital but not enough to be a wealthy rentier….

John:

A while back I read your three part conversation on the Politics of film with David Walsh, and I can’t remember who, but someone on the internet offered their opinion in reponse to what you and Walsh had to say. It’s as follows, and I was wondering how you would respond:

<>

Here it is below:

“Thanks for the link. I recommend the conversation between Steppling and Walsh to my readers.You ask for my response.It would be an interesting exercise to discuss the strengths and weaknesses of their critique of the mainstream media. But I don’t really have time to write the essay your question deserves, so I’ll have to give a fearfully brief answer:

Of course, I share Walsh and Steppling’s disgust with television and most movies; but I disagree with them both about the nature of the artistic problem and the nature of the artistic solution. In other words, their hearts are in the right place, but their understanding of the possible functions of film and television and other media is a bit too simple, in my view.

I don’t have time to say much more, unfortunately: One quick point would be that a political view of art (or a sociological or ideological view of it, the view taken in most university film programs) is far too limited. The imagination is the most radical force for change in the world. Political understandings of and agendas for art are too small, too limited, too narrow. The world that politics and sociology survey (and exert power over) is a tiny, unimportant, marginal one. Most of life takes place elsewhere. Most of what matters in our lives has nothing to do with politics or sociology.

The world of the imagination is the real world and it is a million times larger and more important than the world defined by sociology, ideology, and politics. If people’s imaginations were really free, the other problems Steppling and Walsh decry –the political problems — would be solved as side issues. We must aim higher than aspiring for political change in the world, political relevance in our art, and political truth from the media. We need imaginative change, imaginative relevance, and imaginative truth. We must change more than our social institutions. We must change more than a few ideas. We must free our minds, our hearts, our souls from various forms of enslavement. And once we do that, the political problems will solve themselves.

Only works of the imagination can work on our hearts and emotions at the deepest levels. Political works are not enough. Shakespeare and Rembrandt and Johann Sebastian Bach and William Wordsworth and Henry James are more radical in their implications than the writing of C. Wright Mills, Noam Chomsky, and Howard Zinn (as great as the work of these three is). Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Brandenburg Concertos, Gulliver’s Travels, The Prelude, and Emerson’s Essays are more explosively, world-changingly, radical, dangerous, and liberating than Das Kapital.”

first……@molly:

I agree about shame. And its coupled to humiliation. I think both are indelible in terms of memory, and so the lasting impact is really significant. And in a exhibitionistic culture the surfacing of these mechanisms of shaming are really significant I think. I think the IDF’s treatment of palestinians show they have learned this — and conversly, the domestic police in the US havent learned it……and opposition has adjusted and created a kind of prophylactic subject position in dealing with the authorities….cops, courts, all of it. Which may be why the police and prisons keep resorting to ever more sadistic measures and policies.

I disagree about virno. (not being a strict marxist doesnt make someone superficial)….but this is that weird (I admit) spinozian/hobbsian split that he creates in Grammar of the Multitude. Still, i think thats a very sharp book and I think all those new generation italian leftists are prett y interesting, even if I usually stop short of really finding what they write significant.

As for greek drama…well yeah, thats what im saying. The emotions purportedly on display in the latest Yale Theatre School production of Euripides are fake….they arent emotions, they are vestiges of some weird Oxford iteration of the emotive index……and its just empty. Peter Brook and Blau both had a lot to say about this, and jan kott, and really this was the starting point for grotowski and kanter.

@remy. I had never read that comment. First off its fucking patronizing and irritating and Im curious who wrote it. Its very very very very very immature thinking, and its reactionary to a degree, and mostly its condescending. (my hearts in the right place? fuck off. Really, just fuck right off). Its this valorizing of the a-political sort of fairy tale…….and its simpleton stuff. Oh there is a world beyond politics.–….by definition thats really not true….unless you are some new age dolt or a religious fanatic. Ive read every single book this idiot lists…..and i will bet you dollars to donuts he HASNT read marx. This is the just the airy fairy world of tweet tweet middle brow elitism, and its actually sort of sickening to the soul in a way. And let me add, while I like david walsh personally, and think he has great integrity, i dont agree with the majority of his opinions….he’s a hard core trotskyist and so he has a sort of narrow lens on cultural matters, but on occasion, he does come up with startling insights and analysis. Its just sometimes he is too doctrinaire for me.

That’s an interesting comment

One thing that’s curious is how it declared Capital not so liberating as if it had such pretensions. Capital and the work of Chomsky and Zinn exhibit no illusions about being anything more than resources for people whose concrete struggles alone can liberate them. Some people make extravagant claims for literature’s political efficacy that have no basis; these claims have been around for centuries and nobody making them has ever attempted to substantiate them. But these kinds of claims are not made for works of scholarship. Capital was written in the hope that it would be a tool in the hand of a revolutionary proletariat, not their saviour, prophet, priest, Bodhisattva…

“simpleton stuff”

Yes, and from a recognizable narrative for kidsendummies, the kind of crudest mythology that’s faux erudition

I agree with you John, and I’ll say the guy who wrote that quote lost me when he started spouting off about “imagination”, as that certainly does belong in the realm of fairytale idealism. Great art is fueled by observation, not imagination. The only thing I’ll add is I don’t believe all great artists consciously think in terms of politics or cleanly in terms of right and left. It’s far more nuanced than that. Critiques of bourgeois/middle class values may not necessarily be “political”, but they’re certainly sociological. The guy who wrote that quote I just posted is probably part of what one might call the art=beauty school whereas others might allign themselves with the art as truth school. But then again, “beauty” is a contentious term that lends itself to myriad interpretations. I disagree with the quote overall, but I’d say one must sometimes distinguish between politics and “politics”.

And also, one is essentially making a political stance by “removing” him or herself from politics or “politics”.

And now that I realize, it’s Ray Carney who wrote that quote, a film academic and not a very likeable character, who has had some recent run-ins with the law, but I wanted you to see that quote, nonetheless.

Rembrandt and Bach may not seem “overtly political”, but I also think the world was far different three to four centuries ago. “Political upheaval” as one thinks of it today didn’t even exist back then.

art does not foment revolution.

Art is part of a cultural spectrum……and the reason i do this blog is because I think it has importance. And because I think its maybe more important in this age of electronic media, and hyper marketed mediation of life, than ever before…but thats open to debate.

Look….I think its a sign of youth, and actually a good one, that one is overly enthusiastic (my old friend and mentor of sorts, terry ork, used to say that. He hated sarcasm and put downs. He really felt if you cant voice appreciation, then shut up……and he had a point in a way, and cashiers du cinema at a certain point embraced that idea…for a while anyway). Look….one uses the art that one loves. Maybe its just aesthetic pleasure…..its meditative and maybe its more, its genuine awakening to the usually unseen, and maybe its part of a process indiviually, of loosening repressions. I dont know. But it has a social role, too. And its there that it meets propaganda and has direct political implications. Now, it might in other ways too. I think these are complicated questions. What i think is interesting in this post and it Ngai’s book, is this idea of calculating the tone and affect of an audience and how that intersects with guilt and envy and etc. That to me is significant, actually. For it is usually so unexamined.

Now, i will disagree about something remy. Its not a question of observation or imagination. First off, it takes volumes to start to get a handle on what those words mean. But observation is a sort of illusion in a sense. What is one observing? Mnouchkine said, what is naturalism? If you stare out the window at your dog in the yard, thats naturalistic. If you stare at it for twelve hours, it stops being naturalistic. You observe, but you are not neutral…..history is embedded in your gaze, and your emotions, and pre-conditions. Are you starving or do you desire that upon which you gaze? I mean its a knotted up set of questions. Someone said once, spinoza never travelled more than two miles from where he was born (maybe it was leibniz….doesnt matter) and they said, he should have travelled more. Nietszche said, “or less”. There are narratives of inwardness, and of outwardness. Its not a set of rules, and i happen to tell students, that having a good eye (so called) is often a hinderance.

“Its not a set of rules, and i happen to tell students, that having a good eye (so called) is often a hinderance.”

Interesting, this sort of ties into something else I wanted your opinion on. Do you feel the notion of “artistic talent” is reactionary and bourgeois? For instance, if someone says, “If you want to be a painter or even a filmmaker you should have a strong visual sense.” Or if someone is like “Oh, my son is very talented I think he’ll be a great musician”, or “oh, he/she really has a way with words”, etc.

Are people born a blank slate? Can anyone be the next Bach or Dostoevsky or Nietszche if they’re driven enough? Must one be “gifted”? I personally don’t know.

well, its hard to give a short answer because its sort of a flawed premise. I will say, though, after teaching various kinds of writing for thirty years, that i do believe some people have talent. I dont know what that is, but its something. And its a total mystery to me. As bob fosse always said, i cant make you good….but i can make you better.

While I have no problem with the notion that art is inextricably linked with politics, at the end of the day, couldn’t one stand to reason that artists shouldn’t feel obligated to be philosophers, intellectuals, social critics, or sociologists, and that artists can just be artists? Oftentimes, I feel artists might not always be aware of the political content of the work. They’re not always consciously conceiving of their would-be works from a political standpoint. I had a teacher once who said works of literature often contain symbolism or hidden meanings that even their own creators are unaware of. Ultimately, many, but not all, great artists are really just artisans and aesthetes in the hopes others get enjoyment out of their work and that they’ll be able to make a living even if they don’t necessarily want to be rich. Not all artists are consciously working in the service of some greater political or intellectual cause. Sometimes they’re just artisans composing appealling tunes or painting pretty pictures that actually turn out to be brilliant. Godard once said economy and art can’t be separated from each other.

And yes, I’m essentially trying to demystify the artist.

Not all artistic achievements occur on a conscious or “manual” level. That’s what careerists don’t want to accept, that sometimes your best work produces itself when “the muse arrives” so to speak.

I know the whole notion of “waiting for the muse” has become a cliche, but it’s usually middlebrow hacks more than anyone else who trash the notion of waiting for the muse.

I know may come off as a bit snipey and reactionary every now and then. I don’t disagree with the overall thrust of the arguments you make on this site, but it sometimes requires me to leave my comfort zone, and that’s not always easy I guess.

In my opinion, the relationship of art and politics/society is that of the flower and the soil: a flower cannot enrich the soil from which it grows, but it can reflect the soil’s quality.