Wilhelm Sasnal

“There is a world elsewhere.”

Shakespeare (Coriolanus)

” but the beauty is not the madness

Tho my errors and wrecks lie about me.

and I cannot make it cohere”

Ezra Pound (Canto 116)

“One of the arguments put forward in propaganda for colonizing Ireland in 1594, Virginia in 1612 (and on many similar occasions), was that ‘the rank multitude’ might be exported, ‘the matter of sedition . . . removed out of the City.”

Christopher Hill (Change and Continuity in Seventeenth-Century England )

If I were granted the opportunity to direct another Shakespeare play, it would be Coriolanus. I have long meditated on this late and somewhat problematic (in the Shakespearean sense) play. It is not a part of the so called high tragedies (Hamlet in 1601, Othello in 1604, Lear in 1605, Macbeth and Antony and Cleopatra in 1606). Coriolanus came a year later in 1607, and it marked a break in both structure and sensibility. I have always pondered the order of composition of the tragedies because that order feels counter-intuitive somehow. I directed an experimental King Lear in Poland, with Mick Collins and Polish actor Marian Opania. I had two Lears on stage throughout and the play was performed in three languages (English, Polish, and Norwegian). I did an experimental version of The Tempest in LA (really it was a company experiment but I was the artistic director of that company), and another experimental Macbeth, also in LA. It is likely that Hamlet was Shakespeare’s greatest achievement but that is one of those questions that is endlessly qualified. But of all Shakespeare’s plays, Coriolanus feels the most contemporary. For Caius Martius (Coriolanus) is without the profound inner life of the other tragic protagonists in the Shakespeare canon. In fact, he almost has no inner life. And it is that rather mediated emptiness (it IS still emptiness) that makes him feel so modern.

“…in fourteen consecutive months Shakespeare had created Lear and the Fool, Edgar and Edmund, Macbeth and Lady Macbeth, and Antony and Cleopatra. Compared with that eightfold, in personality or in character Caius Martius scarcely exists. Had Shakespeare wearied of the labor of reinventing the human, at least in the tragic mode? There is little inwardness in Caius Martius, and what may be there is accessible neither to us nor to anyone in the play, including Caius Martius himself.”

Harold Bloom (Shakespeare, The Invention of the Human)

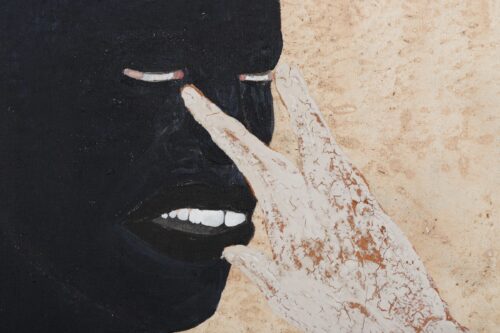

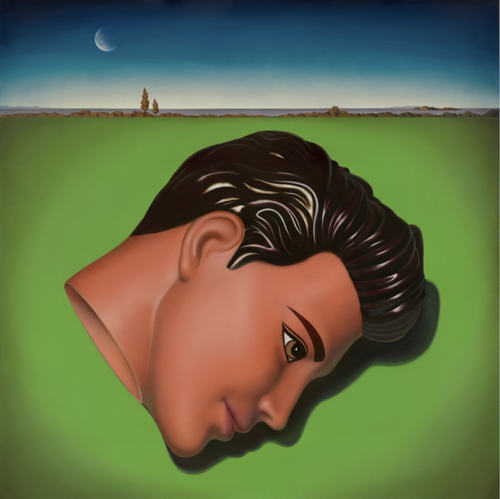

Kelton Campos Fausto

One of the curious (and revealing, on several levels) aspects of the critical response, over the years (and centuries) to this late Shakespeare, is the zeal with which T.S.Eliot defended it. In fact Eliot called it Shakespeare’s greatest work. Now I remember thirty years ago coming across Eliot and his ideas on Coriolanus, and feeling vindicated a bit because on some level I had begun to feel the same way. And more revealing still is the popular (sic) response to Eliot’s opinion. David Haglund, managing editor of The New Yorker (that barometer of white middle brow taste), who wrote a snide and patronizing article about how deluded Eliot was and in fact calling Eliot’s opinions on the play ‘zany’ and ”incomprehensible’. In fact it is worth quoting some of it because I cannot do justice to that particular offensive tone of whiteness.

“It’s here that Eliot delivers his contrarian coup de grace, bypassing all the other likely candidates for Shakespeare’s greatest tragedy—King Lear, Macbeth, Othello—and declares that the title rightly belongs to Coriolanus, one of the Bard’s least-read plays: ‘Coriolanus may be not as “interesting” as Hamlet, but it is, with Antony and Cleopatra, Shakespeare’s most assured artistic success. And probably more people have thought Hamlet a work of art because they found it interesting, have found it interesting because it is a work of art. It is the Mona Lisa of literature'{ } Eliot’s argument continues to fly so fully in the face of conventional wisdom that, to this day, his semi-offhand comment about Coriolanus may be the most famous thing about the play. .”

David Haglund (Is Coriolanus Shakespeare’s Greatest Tragedy? A closer look at T.S. Eliot’s zany claim. New Yorker)

Now, Haglund goes on to say the ten year old Ralph Fiennes film adaptation of Coriolanus is an effective action thriller. In fact, a ‘tightly plotted action thriller’…and that screenwriter John Logan was able to do this because Shakespeare’s play is itself ‘a tightly plotted action thriller’. You see how philistine critics are so much more comfortable discussing tightly plotted action thrillers than they are anything a bit more complex — like, oh, tragedy. I remember Ben Affleck once pontificating that Shakespeare would clearly have made a great screenwriter. Now this 2011 film of Coriolanus was embraced by Zizek who sees it as a parable (or something) of the radical left, and why communists are anti democratic, or something. (Fiennes’ film is shot in Belgrade, which Zizek sees as somehow significant). After trashing communism Zizek always ends with, ‘speaking as a Stalinist…” and then says something racist and fascist. Thats his schtick. Ok, none of this has much to do with my post but it does suggest why Eliot was right.

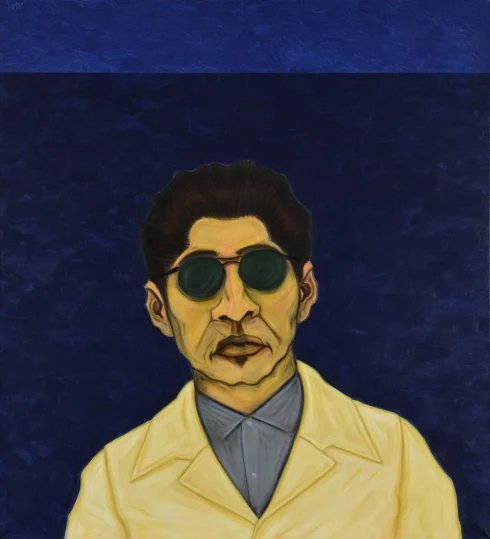

César Martínez

And it is another example of how stunningly conformist is white elite Academia and how the glossy magazines of the educated classes have become, if they weren’t before, slaves to group think. But the Fiennes adaptation was set (sort of) in the Middle East. Now, in the midst of a genocide of Gaza, this fact entails a bit more resonance. It also is suggestive of the ambivalence felt about the so called ‘Middle East’ in western popular culture. And in fact, on all levels of the culture. And I think the Shakespeare play itself, Coriolanus, is naturally suited as the avatar for this ambivalence.

Eliot began a sequence of poems titled Coriolan, with reference to the Shakespeare play (and to the Beethoven overture), and it was as close as Eliot ever got to direct political commentary. And mostly this unfinished sequence has been largely forgotten. It is hard to determine exactly what the consensus is on Eliot at the moment anyway. When I was a teenager and I began to read Eliot there was a feeling that he represented something of absolute merit in English literature. And certainly in poetry. I am not sure that is the case today.

“It is striking that these early aesthetic and technical judgments about Shakespeare’s tragedies became for Eliot consistently important into his mature career, and frequently lie behind his more famous mature declarations of similar ideas. { } What is marked, however, is not just the consistent development of the technical or literary features of his favored Shakespearian dramas into broader philosophical themes in Eliot’s thinking, from the late 1910s into the late 1920s. Within that development, there is in Eliot persistence of an interest in Shakespeare’s (and, much less so, in Jonson’s) Roman plays as touchstones within and behind this thinking. Indeed, Shakespeare’s Roman plays were significant instigators for Eliot’s poetic self-redirection after The Waste Land. The tragic sense of inadequacy and failure from Julius Caesar shadows “The Hollow Men” (1925), which derives its title from Shakespeare’s play. Those brief lyrics deploy allusion to Julius Caesar in order to bring awful plangency to its realization of the “Shadow”of death or disappointment which “falls” “Between the motion / And the act” (Collected Poems 92).”

Steven Matthews (You can see some eagles. And hear the trumpets”: The Literary and Political Hinterland of T.S. Eliot’s Coriolan)

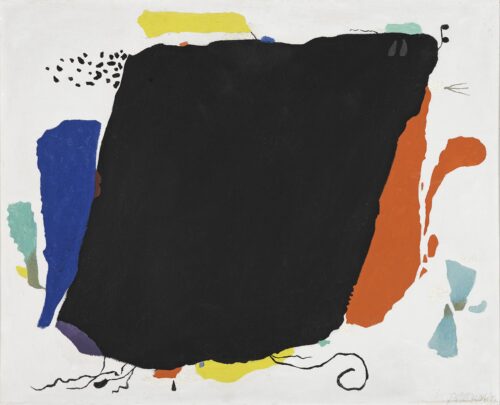

Willi Baumeister

Eliot saw in Coriolanus something deeply relevant to the rise of Hitler. And one might, by extension see something in both Eliot’s analysis and in the Shakespeare play, something relevant to Pete Hegseth, and Marco Rubio, Gavin Newsome, Joe Biden, and Donald Trump.

“Thou hast described

A hot friend cooling: ever note, Lucilius,

When love begins to sicken and decay,

It useth an enforced ceremony.

There are no tricks in plain and simple faith;

But hollow men, like horses hot at hand,

Make gallant show and promise of their mettle;

But when they should endure the bloody spur,

They fall their crests, and, like deceitful jades,

Sink in the trial.”

Shakespeare (Julius Caesar, Act 4, sc.2, Brutus speaking)

As a playwright I often feel I get a sense of how plays of other writers are written, what sort of inspiration spurred the project. While I love The Tempest, for example, it has that feel of a play that began with a great idea, an event (shipwreck in Bermuda), and yet that first inspiration began to dissipate before the end. The playwright, one can feel, is losing enthusiasm. The idea was not as good as he first thought.

“…that Shakespeare’s Hamlet, so far as it is Shakespeare’s, is a play dealing with the effect of a mother’s guilt upon her son, and that Shakespeare was unable to impose this motive successfully upon the “intractable ’’’ material of the old play. Of the intractability there can be no doubt. So far from being Shakespeare’s masterpiece, the play is most certainly an artistic failure.”

T. S. Eliot (The Sacred Wood)

Hamlet is Shakespeare’s longest play, and the one with the most extraneous scenes. And Eliot is no doubt correct in thinking it was the most difficult play for Shakespeare to finish.

“We are surely justified in attributing the play, with that other profoundly interesting play of ‘intractable’ material and astonishing versification, Measure for Measure, to a period of crisis, after which follow the tragic successes which culminate in Coriolanus.”

T.S. Eliot (Ibid)

Sabino Guisu

While I might take some issue with the following, I also recognise the legitimacy of Eliot’s point.

“Hamlet (the man) is dominated by an emotion which is inexpressible, because it is in excess of the facts as they appear. And the supposed identity of Hamlet with his author is genuine to this point: that Hamlet’s bafflement at the absence of objective equivalent to his feelings is a prolongation of the bafflement of his creator in the face of his artistic problem. “

T.S. Eliot (Ibid)

This is Eliot’s insistence on an ‘objective correlative’. Those who revere Hamlet see the lack of the objective correlative as existential, the birth of a kind of modern thought.

Harold Bloom, for example:

“Hamlet appears too immense a consciousness for Hamlet, a revenge tragedy does not afford the scope for the leading Western representation of an intellectual. But Hamlet is scarcely the revenge tragedy that it only pretends to be. It is theater of the world, like The Divine Comedy or Paradise Lost or Faust, or Ulysses, or In Search of Lost Time. Shakespeare’s previous tragedies only partly foreshadow it, and his later works, though they echo it, are very different from Hamlet, in spirit and in tonality. No other single character in the plays, not even Falstaff or Cleopatra, matches Hamlet’s infinite reverberations.”

Harold Bloom (Ibid)

I often complain about authors who forget they are writing crime stories (for example), or filmmakers (even more often). They forget the crime to focus on ‘the meaningful’. They forget that the ‘meaningful’ is represented, symbolized, by the crime. That you cannot leave the concrete for the abstract, as a writer. But Hamlet is not a revenge tragedy. It is, certainly, something else. But it does suffer from the neglect the author shows to revenge itself.

Penelope Haralambidou

“…but if I had to guess at Shakespeare’s self-representation, I would find it in Falstaff. Hamlet, though, is Shakespeare’s ideal son, as Hal is Falstaff’s. My assertion here is not my own; it belongs to James Joyce, who first identified Hamlet the Dane with Shakespeare’s only son, Hamnet, who died at the age of eleven in 1596, four to five years before the final version of The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, in which Ham net Shakespeare’s father played the role of the Ghost of Hamlet’s father. “

Harold Bloom (Ibid)

This is very telling and no doubt correct. For all its oddness, Hamlet is a tragedy. Perhaps more than any other of Shakespeare’s plays, in fact. Coriolanus, however, is something like a societal tragedy. The audience doesn’t care about Caius Martius, partly because he cares only about himself (though not entirely). But they care how such a man, how such men, become wielders of power, how that power can come to effect their own lives.

“Coriolanus, I would venture, is Shakespeare’s reaction-formation, or belated defense, against his own Antony, a much more interesting Herculean hero. Since Coriolanus was composed just after Antony and Cleopatra, Shakespeare would have been peculiarly aware of the discontinuity between the two Herculean protagonists. Antony, very much in decline, nevertheless retains all of the complexities, and some of the virtues, that made him a superb personality. Insofar as Coriolanus has any personality at all, it is quite painful, to himself as well as to others.”

Harold Bloom (Ibid)

This emptiness is what makes Caius Martius a stricken modern, a man caught in times of emptiness, or at least in a situation for which he hasn’t the intellect to analyse. And this is really the point here. On the last podcast (Aesthetic Resistance substack) the character of Trump’s ICE agents was discussed. Who are such men? Who were the guards at Abu Ghraib and who are they at Israeli prisons?

https://www.btselem.org/publications/202408_welcome_to_hell

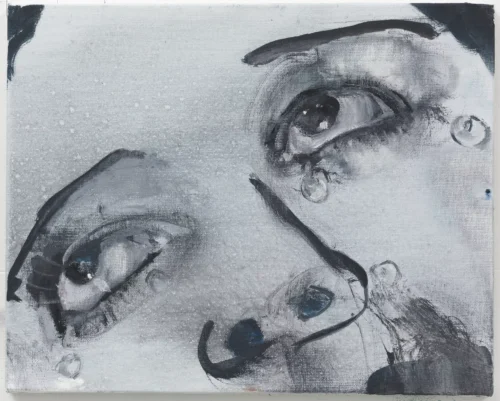

Marlane Dumas

This is the core of Coriolanus, I think. Pete Hegseth is the perfect Caius Martius, if he were an actor (well, he is, but never mind) because he is just as empty. And just as caught in a field of panic and almost bewilderment. And the populace looks to him, or Tel Aviv Ted, or Huckabee (and poor Huck is visibly demented, his glassy stare will one day become one of the many avatars of the Trump second term). The populace asks for something such men cannot give. And on those terms Hegseth is more of an ‘wannabe’ Caius Martius.

On another tier, the very wealthy 1%, perhaps now personified by Bezos and Zuckerberg and Musk, are men in extreme isolation. The isolation is unmediated by the surrounding flattery and lack of challenge. It is worth noting that Eliot, in his role as editor of The Criterion (throughout the 1930s) tended toward conflation of Fascism, nationalism and communism. And even Christianity. Eliot must have recognized himself in his own poems The Hollow Men.

“Shape without form, shade without colour.

Paralysed force, gesture without motion;

Those who have crossed

With direct eyes, to death’s other Kingdom

Remember us—if at all—not as lost

Violent souls, but only

As the hollow men “

T.S. Eliot (The Hollow Men)

Eliot was in a kind of self isolation. Famous men often are. More than famous women, and I’m not sure why that is.

“Words kill, because in tragedy they are part of a conflict that becomes rapidly radicalized to the point that death becomes unavoidable. { } Beam of the sun, fairer than all that have shone before for seven-gated Thebes, finally you shone forth, eye of golden day” (Sophocles). The long night has ended, the Seven have been defeated, Thebes is saved, war is over – tragedy has already begun. Hamlet opens, like Agamemnon, at night: a group of soldiers atop a castle, nervous, talking of recent wars and wondering about current threats; a ghost in battle armor appears. But in the next scene the King sends an embassy to Norway, and the war is avoided. An army will eventually cross the stage, but is headed elsewhere. War is close, but is not inside the play.A war that simultaneously is there, and isn’t. It is there in order to shatter the constraints of ordinary life, unleashing the violence that is necessary for tragic plots. Macbeth’s double opening: the witches – and the battle that reveals Macbeth’s capacity for killing. But they’re really the same thing. War is what liberates the witches. What was dark and unthinkable comes into the open. { } War as a trigger for tragedy, then – but almost never as its core. Because war is usually waged against an external enemy – Persians, Turks, Protestants, the enemies of Brandenburg, whatever – whereas tragedy focuses on internal enemies. Civil war. “The war within the family”, as the French classicist Nicole Loraux has called it in a great essay (Loraux 1997): Seven Against Thebes, with the two brothers who kill one another in front of their city; Lear’s daughters, Nero and Britannicus, Karl and Franz Moor… And then the oedipal thread of children against parents and parents against children – Oedipus, Orestes, Electra, Hamlet, Segismundo, Carlos.”

Franco Moretti (Words Kill)

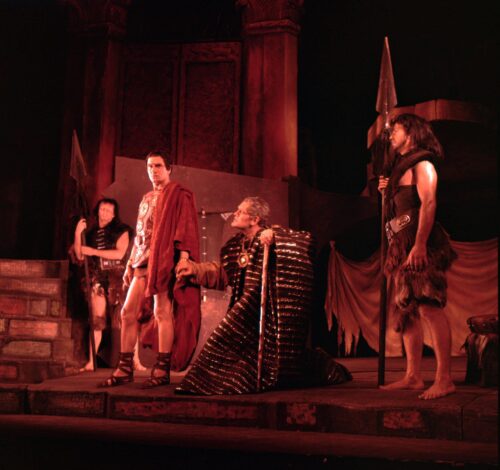

Laurence Olivier as Coriolanus, Harry Andrews as Menenius, 1959 RSC, Peter Hall dr.

There is always a war within.

“Commenting on the first Coriolan poem, “Triumphal March,” Ronald Bush claims that Eliot’s

intention was to make a “piece of political satire,” but ended up with a piece displaying ‘private nightmare’.”

Steven Matthews (Ibid) (quoting Ronald Bush T.S. Eliot: A Study in Character and Style)

William Empson derided the anti-humanism of Eliot (and Pound and Lewis and Shaw) and therefore he identifies why Eliot remains of some perverse value. But it is worth looking at Coriolanus and then at Shakespeare’s final bit of writing — two fifths of Two Noble Kinsmen. (Fletcher wrote the rest). I have long been fascinated, if not almost obsessed with this last (almost) unplayable drama of Shakespeare. Why he agreed to write it, why he was thereafter silent, is an enduring mystery. And I only mention it here (I hope eventually to write out all my confused and obsessive thoughts on it) because in the language, the poetry, of this final work can be found something stunningly modern. It is the most elliptical of Shakespeare’s plays, and really it barely qualifies as dialogue. It is something else.

“As far as we can know, the Shakespearean portions of The Two Noble Kinsmen (1613) constitute the final writing of any sort by the author of Hamlet and King Lear. I have never seen a performance of The Two Noble Kinsmen, and don’t particularly want to, since Shakespeare’s contributions to the play are scarcely dramatic. Critics of The Two Noble Kinsmen generally disagree, but I find Shakespeare’s style, in this final work, to be subtler and defter than ever, though very difficult to absorb. His purposes here are very enigmatic; he abandons his career-long concern with character and personality and presents a darker, more remote or estranged vision of human life than ever before. Pageant, ritual, ceremony, whatever one chooses to call it, Shakespeare’s share in The Two Noble Kinsmen is poetry astonishing even for him, but very difficult poetry, hardly suitable for the theater.”

Harold Bloom (Ibid)

This last play, or Shakespeare’s part, is closer to Wallace Stevens than to Fletcher or Jonson or Kyd. I also think it conjures Büchner, both of Danton’s Death and Woyzeck. (Büchner died at 23, of typhus). But also of Büchner’s novella, Lenz. Hamnet, Shakespeare’s son, who died at 11, had a twin sister (Judith) who survived. Such details are haunting, as is the premature death of Büchner. It is now believed Hamnet died of bubonic plague (but there are other theories). Two Noble Kinsmen is almost impossible to discuss. And almost impossible to read.

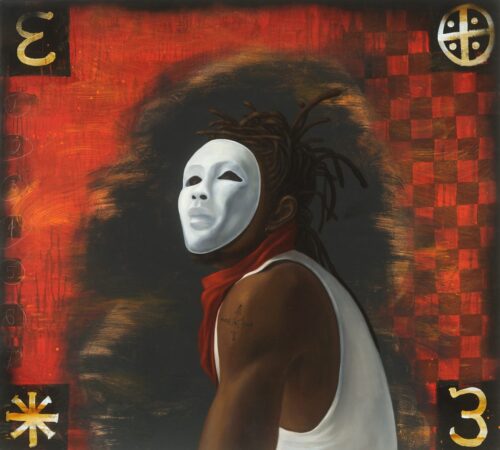

Renee Stout

But my point here is that today’s most visible politicians are also, likely, not very powerful at all. This is an age of the Mask, the ventriloquist, and the ventriloquist’s dummy. Coriolanus is, finally, a play about the state. Another admirer of this least performed Shakespeare tragedy was Bertolt Brecht, who had planned an adaptation of the play and saw it was the betrayal of the people by a necessarily fascist leader. And it is worth noting that in nearly all of the scenes in the play crowds are present.

“No doubt the dryness of Coriolanus must have had a discouraging effect on readers and audiences. The play is, indeed, harsh and austere. But the austerity of dramatic matter does not sufficiently explain the dislike almost universally felt for so long for one of Shakespeare’s most profound works. In my view the reasons for this dislike must be looked for elsewhere. It resulted from the ambiguity of Coriolanus—political, moral, and, in the last resort, philosophical. It was the sort of ambiguity difficult to swallow. { } But fate, as visualized by Shakespeare, although it pursues, corners and breaks the hero in the mode of Greek furies, has a modern aspect. Fate is represented here by class struggle. Rome is a city state. But it is a Rome of plebeians and patricians. The action of Coriolanus takes place after the expulsion of kings in the half-legendary times of the early Roman Republic.”

Jan Kott (Shakespeare Our Contemporary)

Kott remains an astute reader of Shakespeare. In some ways, the very most astute.

“Coriolanus still has a mark of grim greatness and is crushed by history. But the history that breaks Coriolanus is not royal history any more. It is the history of a city divided into plebeians and patricians. It is the history of class struggle. History in the royal chronicles, and in Macbeth, was a Grand Mechanism, which had something demonic in it. History in Coriolanus has ceased to be demonic. It is only ironic and tragic. This is another reason why Coriolanus is a modern play.”

Jan Kott (Ibid)

Pierre de Clausades

A nameless citizen declares in the first scene of the play:

“The leanness that afflicts us, the object of our misery, is as an inventory to particularize their abundance; our sufferance is a gain to them.”

Shakespeare (Coriolanus)

Shakespeare as Marxist. Menenius Agrippa enters. Speaks to the crowd. Yes there is famine but not because the patricians have too much but because this is the will of the Gods. There is nothing you can do to change that. Agrippa speaks in verse, the citizens in prose. Keir Starmer as Agrippa.

“Shakespeare’s battle scenes are accompanied by drum beats and the sound of trumpets. But there is little noise in them. They take place on an empty stage. Great battles are fought by a handful of soldiers. Of course, at the Globe, red paint was not spared, and swords clattered against each other for long stretches of time. But Shakespeare’s battle scenes are neither descriptive nor intended to create a make-believe. Theirs is a dramatic quality of a different, inner kind. Mortal duels are punctuated by bitter philosophic reflection, or by irony.”

Jan Kott (Ibid)

There is always a war within. One of Kott’s great insights was to see the inherent uniqueness of the ‘stage’. The empty stage more specifically. Writing of the Mad Tom and Gloucester scene (King Lear) on the heath…

“It is easy to imagine this scene. The text itself provides stage directions. Edgar is supporting Gloucester; he lifts his feet high pretending to walk uphill. Gloucester, too, lifts his feet, as if expecting the ground to rise, but underneath his foot there is only air. This entire scene is written for a very definite type of theatre, namely pantomime. This pantomime only makes sense if enacted on a flat and level stage. Edgar feigns madness, but in doing so he must adopt the right gestures. In its theatrical expression this is a scene in which a madman leads a blind man and talks him into believing in a non-existing mountain. In another moment a landscape will be sketched in. Shakespeare often creates a landscape on an empty stage. A few words, and the diffused, soft afternoon light at the Globe changes into night, evening, or morning. But no other Shakespearean landscape is so exact, precise and clear as this one. { } The scene of the suicidal leap is also a mime. Gloucester kneels in a last prayer and then, in accordance with tradition of the play’s English performances, falls over. He is now at the bottom of the cliff. But there was no height; it was an illusion. Gloucester knelt down on an empty stage, fell over and got up. At this point disillusion follows. The non-existent cliff is not meant just to deceive the blind man. For a short while we, too, believed in this landscape and in the mime. The meaning of this parable is not easy to define. But one thing is clear: this type of parable is not to be thought of outside the theatre, or rather outside a certain kind of theatre.”

Jan Kott (Ibid)

The stage is always the scene of the primal crime. It is always our stage, in our mind, and it always recreates our story.

Roman Opałka

The unpopularity of Coriolanus resides in its ambivalence. The world does not cohere. There is no ‘rooting interest’ as they used to say in Hollywood story meetings. Today there are only the ventriloquist dummies parroting various cliches that cannot be kept track by many. Leaders are obviously not really making key policy decisions. Institutions like the EU provide obscene amounts of air time to literally deranged bureaucrats. Is Trump a decision maker? Is Peter Thiel? Is Frau Von der Leyen? Larry Fink or Jeff Bezos? The state is ever more amorphous. What role does Mossad play in daily life in North America and Europe. That Jeffrey Epstein may go down in history as the most important individual of the early 21st century is its own parable. And yet I can imagine a Shakespeare making Epstein a central character in a contemporary tragedy. Although tragedy feels impossible today, and often critics suggest the ‘grotesque’ is all that can be achieved. The ascension of genre is part of this problem — and that, as in Coriolanus, ‘Fate’ is now class struggle. Marx inscribed his autopsy of Capitalism indelibly. Epstein then as a character in a Shakespearean murder mystery. A murder mystery without an actual murder.

“Yet Frye’s identification of narrative in general with the particular narrative genre of romance raises the apparently unrelated issue of genre criticism, which, though thoroughly discredited by modern literary theory and practice, has in fact always entertained a privileged relationship with historical materialism. { } The strategic value of generic concepts for Marxism clearly lies in the mediatory function of the notion of a genre, which allows the coordination of immanent formal analysis of the individual text with the twin diachronic perspective of the history of forms and the evolution of social life. Meanwhile, in the other traditions of contemporary literary criticism, generic perspectives live something like a “return of the repressed.”

Fredric Jameson (The Political Unconscious)

I wonder where this ‘thoroughly discredited’ criticism is to be found? The problem with Jameson’s take here is society and its culture change, at least as much and probably more, than narrative writing. I have noted before that today everything is genre. Shakespeare is writing a ‘tightly plotted action thriller’. And if you have worked in Hollywood you know the hyphenating of genre forms is commonplace (An action romantic comedy, a space western, a chick-flick detective story, etc)

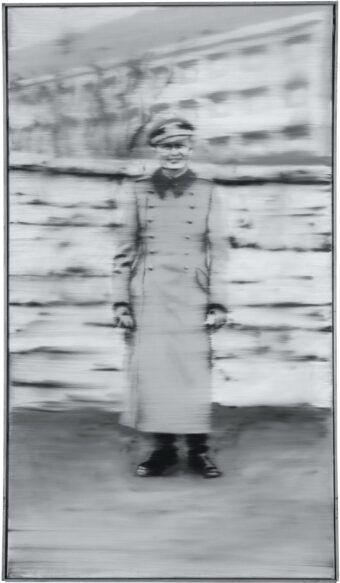

Gerhard Richter (Uncle Rudi)

Fredric Jameson (Ibid)

There are other examples of liberal ‘virtue signaling’ in taste, connected to this weird dependency on ‘naturalism’ (or realism). The blue ribbon for just competing syndrome that praises dreadful community centre murals, or the intentional touch of amateurishness that grants the artist a quality of proletarian authenticity. The left is often more guilty of romanticizing kitsch than the right, its just a different kind of kitsch.

That said, I feel Moretti a better guide to the implications of genre than Northrup Frye. Moretti’s Dialectic of Fear is one of the great essays on genre ever written https://www.umsl.edu/~gradyf/theory/moretti.pdf

And it is in this essay that Moretti captures something essential about ‘genre’.

“The fear of bourgeois civilization is summed up in two names: Frankenstein and Dracula. The monster and the vampire are born together one night in 1816 in the drawing room of the Villa Chapuis near Geneva, out of a society game among friends to while away a rainy summer. Born in the full spate of the industrial revolution, they rise again together in the critical years at the end of the nineteenth century under the names of Hyde and Dracula. { } Frankenstein and Dracula lead parallel lives. They are two indivisible, because complementary, figures; the two horrible faces of a single society, its extremes: the disfigured wretch and the ruthless proprietor. The worker and capital: ‘the whole of society must split into the two classes of property owners and propertyless workers.”

Franco Moretti (Dialectic of Fear)

But Jameson notes something else important here, too. And relevant to Coriolanus, and that is to be found in Romance.

“A first specification of romance would then be achieved if we could account for the way in which, in contrast to realism, its inner-worldly objects such as landscape or village, forest or mansion—mere temporary stopping places on the lumbering coach or express-train itinerary of realistic representation—are somehow transformed into folds in space, into discontinuous pockets of homogeneous time and of heightened symbolic closure, such that they become tangible analoga or perceptual vehicles for world in its larger phenomenological sense. Heidegger’s account goes on to supply the key to this enigma, and we may borrow his cumbersome formula to suggest that romance is precisely that form in which the *worldness* of world reveals or manifests itself, in which, in other words, world in the technical sense of the transcendental horizon of our experience becomes visible in an inner-worldly sense.”

Fredric Jameson (Ibid)

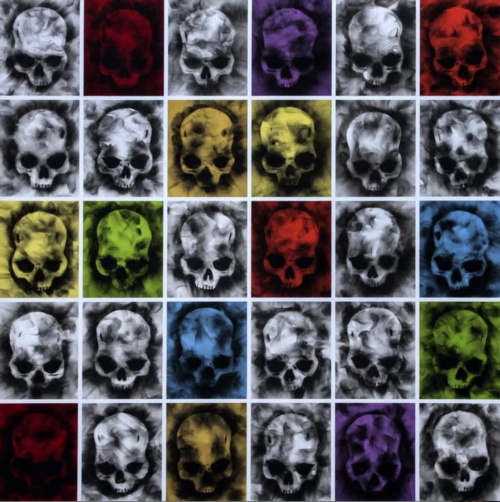

Sun Yitian

In a sense, this is obvious. All narrative creates folds in space. The carriage journey, with a stop at the Inn, was a ritual or ceremonial manufacturing of reverie. And it is in such reveries that the ‘world’ comes to exist. Or something like a world. Jameson adds, rightly; “What is misleading is the implication that this “nature” is in any sense itself a “natural” rather than a very peculiar and specialized social and historical phenomenon.”

This ‘is’ right, but it begs a couple other questions. It is not natural in the sense of universal, but it is something , or some version of it, that exists as far back as narrative writing exists. This is what story telling is, and it is certainly found in folk tales and fairy tales. And in genre forms today, like movie westerns, a version is ‘the night-time or twilight chat down by the river’ scene. These interludes are like ‘waiting moves’ in chess. It is also not unlike a ‘safety’ in pool (pocket billiards if you prefer).All such pauses are caesura of a kind. It is also related to ellipsis. Some writers, Patricia Highsmith is an example, are often almost entirely elliptical. And Coriolanus, again, features structural elliptical elements. Far more than any other Shakespeare. Another reason for its unpopularity.

“Any “first-hand” contact with the original mythic narratives themselves (and for many readers, Levi-Strauss’s four-volume Mythologiques will have served as a vast introductory manual of these unfamiliar and unsettling strings of episodes, so utterly unlike what our childhood versions of Greek myth led us to expect) suggests that later notions of “character” are quite inappropriate to the actants of these decentered and preindividual narratives. Even the traditional heroes of Western art-romance, from Yvain and Parzival to Fabrice del Dongo and the Pierrot of Queneau, or the “grand Meaulnes” of Alain-Fournier and the Oedipa Maas of Pynchon’s Crying of Lot 49, far from striking us as emissaries of some “upper world,” show a naivete and bewilderment that marks them rather as mortal spectators surprised by supernatural conflict, into which they are unwittingly drawn, reaping the rewards of cosmic victory without ever having quite been aware of what was at stake in the first place.”

Fredric Jameson (Ibid)

Steven Shore, photography.

The Pynchon example is inspired. And it is one of the qualities that triggers the paranoia (the modern paranoia) that is so representative of Pynchon. For in Pynchon, there is a sense that society has passed over into a state of nihilistic erasure. Contemporary audiences, of film or literature, have paradoxically (perhaps) come to feel disproportionately uncomfortable with the elliptical. Almost as if there is paranoia enough in daily life that I don’t need it in ‘entertainment’. Now Jameson discusses Derrida at this point and I will only say that when I read this:

“the influential version of Jacques Derrida, whose entire work may be read, from this point of view, as the unmasking and demystification of a host of unconscious or naturalized binary oppositions in contemporary and traditional thought, the best known of which are those which oppose speech and writing, presence and absence, norm and deviation, center and periphery, experience and supplementarity, and male and female. Derrida has shown how all these axes function to ratify the centrality of a dominant term by means of the marginalization of an excluded or inessential one, a process that he characterizes as a persistence of “metaphysical” thinking.”

Fredric Jameson (Ibid)

I am tempted to suggest a reading of William Empson’s Seven Types of Ambiguity is in order. Jameson does his own corrective by introducing Nietzsche at this point. And the ideological as-a-meditation-on-ethics. But that is for another post. A final quote, however, is in order:

Todd Hido, photography.

“Yet surely, in the shrinking world of the present day, with its gradual leveling of class and national and racial differences, and its imminent abolition of Nature (as some ultimate term of Otherness or difference), it ought to be less difficult to understand to what degree the concept of good and evil is a positional one that coincides with categories of Otherness.”

Fredric Jameson (Ibid)

I will only add that there has been no leveling that I can see, and, more importantly the world is not shrinking. The experience of shrinking is an expression of class domination, and a carefully manufactured illusion. And great art, whatever one means by that, has as one of its roles, to puncture that illusion. And that comes at a cost. And it may be that pleasure or diversion is a part of that cost. I remember in the early days of television how this or that was ‘going to be brought right into your living room’. Of course it wasn’t. Something else was. A kind of nothing.

“Ferdinand:

My sister, O my sister! there’s the cause on’t.

Whether we fall by ambition, blood, or lust,

Like diamonds, we are cut with our own dust. (Dies)

Cardinal:

Thou hast thy payment too.

Bosola:

Yes, I hold my weary soul in my teeth;

’Tis ready to part from me. I do glory

That thou, which stood’st like a huge pyramid

Begun upon a large and ample base,

Shalt end in a little point, a kind of nothing.”

John Webster (Duchess of Malfi, 1613, Act V, sc. 5)

To donate to this blog, and to the Aesthetic Resistance podcasts, use the paypal button at the top of the page.

Speak Your Mind