Wouter VanderVoorde, photography (Canberra, Australia) 2019.

“Many works of the ancients have become fragments. Many works of the moderns are fragments as soon as they are written.”

Friedrich Schlegel (Philosophical Fragments)

“Then one day you wake up and your seventy. Looking ahead you see a black doorway.You begin to notice the black doorway is always there. At the edge, whether you look at it or not. Most moments contain it, most moments have a sort of sediment of black doorway at the bottom of the glass.”

Anne Carson (lecture ‘Beware the man whose handwriting sways like a reed in the wind’, London Review of Books)

“Only a word book makes it possible to hold the student responsible…because it provides them with a reliable tool for finding and correcting their mistakes…It is absolutely necessary that the student can correct their own mistakes. They should feel confident that they are the only author of their work and they alone ought to be responsible for it.”

Ludwig Wittgenstein ( Word Book { Wörterbuch für Volksschulen}, children’s dictionary 1925)

“If you tried to doubt everything you would not get as far as doubting anything. The game of doubting itself presupposes certainty.”

Ludwig Wittgenstein (On Certainty)

love/hate. This is really about that black doorway.

So much today is hated. Criticism has become snark but also simply disguised hatred. Snark IS hate. Snark is also self-hate.

In a world today in which media and the state both lie, are both proven liars, this loss of trust bleeds into personal relationships. Did Macron hide a napkin or cocaine? Was the NBA lottery rigged? Did Israel lie about Oct 7th. What about AFRICOM and Michael Langley and Burkina Faso? Is Burkina Faso slaughtering people in nearby regions? We know the answer to all these questions. Or almost all of them. One might be other than we believe. But what does that mean? Here is where language becomes an actual issue. History tells us General Langley is lying (he might even believe what he says, I have no idea). Did Israel lie? Of course. They lie about everything. Is big time sports full of liars and driven by maximizing profit? Yes of course. Does that mean the lottery was rigged? Probably but its also remotely possible it was not. Did Macron hide his packet of coke very quickly when the cameras arrived? I don’t know but it doesn’t matter honestly. He is a malicious little predator and serial liar so, as I say, it doesn’t matter.

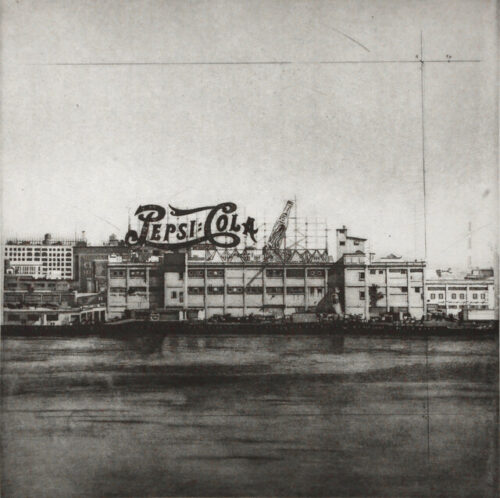

Michelle Stuart (ambrotypes) 2021.

His gestures were furtive. Why hide a napkin with a sheepish look on your face? (the Oxford Dictionary defines ‘sheepish’ this way: showing or feeling embarrassment from shame or a lack of self-confidence). Macron does not, actually, lack self confidence. And, strictly speaking, I don’t think you can shame him. He is well beyond these things.

But there is another idea, utterly separate, that has crept into my thoughts, a companion to that black doorway.

“Philosophy’s failure to change the world and thus forestall catastrophe puts into question philosophy’s survival. Addressing this, Adorno opens his magnum opus with a reference to Karl Marx’s “summary judgment that [philosophy] had merely interpreted the world, that resignation in the face of reality has crippled it.” He sees Marx’s thesis engendering “a defeatism of reason after the transformation of the world miscarried.” Adorno’s own dialectical alternative to such defeatism bears repeating: “Having broken its pledge to be as one with reality or at the point of its production, philosophy is obliged ruthlessly to criticize itself.” It is this double movement of “failure and promise” that characterizes negative dialectics: Philosophy’s failure to forestall suffering calls for ruthless auto-critique, which becomes a condition of possibility for transformative praxis—hence also the promise of critical philosophy to become actuality.”

SD Chrostowska (Adorno’s Senses of Critique: Gesture, Suffering, Utopia)

This idea, that ‘thinking’ must provide tangible results, material change, that it must not continue on for too long without progress of some sort — this idea is insidious and insanely prevalent in western societies today, among the educated (sic) anyway. But this is a symptom. A symptom of a certain sclerosis of the imagination, coupled to this ‘hatred’ of self and others. Thinking must justify itself. Leftists, young liberals mostly, are forever asking ‘but what should we do’? I have many older left leaning people ask this, too. They either adapt a tone of challenge or they ask meekly — nicely —‘but what do you think we should do’? And I think this is, firstly, a sign of privilege. These questions almost always come from white people. As Adorno said, at the end of his life, in an interview, when he was asked this……’I don’t know’, he said. ‘I don’t know’ means I will go on trying to think through the myriad and complex problems of life and society. As well as keeping an eye on that black doorway. So it is not a matter of simply wanting a simple ‘solution’ to what is an amorphous and complex question, but more that the public today, the educated (sic) public lack trust in themselves to figure it all out. Questions of a philosophic nature are intimidating. And appeal to any official authority on truth tends to be believed, even if there is a record of mistakes on the authorities part. Take the fact checkers on social media (there are many, some anonymous and some like GROK, a generative AI chatbox that came out of an Elon Musk project, apparently.) I know otherwise very intelligent people who will refer me to articles in major news organizations (NY Times, London Times, BBC, or here in Norway Aftenposten, etc) to prove or disprove something I had mentioned earlier. There is a clear anxiety about not ‘knowing’ the official version of things.

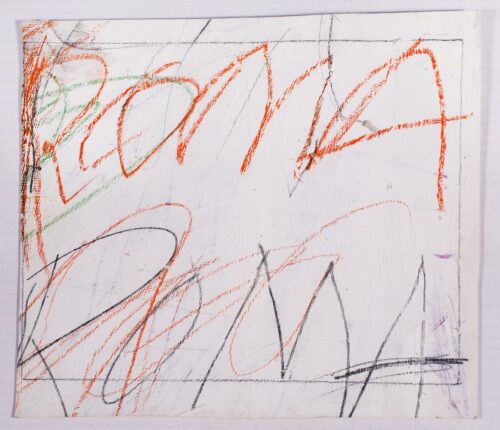

Cy Twombly

In a society in which official organs of information are so unreliable, the unofficial version of events take on a kind of totemic ceremonial quality. In other words its not about believing the institutional news outlet or fact checker, but only that this outlet or chatbox occupies this role and is given some kind of societal Imprimatur. And it occurs to me that the Church (and Ive been thinking about the Catholic Church, unsurprisingly, of late) functions this way today and perhaps has for a long time. One must consult the fact-checking, much as people once consulted the Oracle at Delphi. Read the tea leaves. Analyse the utterances of GROK.

“I did not get my picture of the world by satisfying myself of its correctness, nor do I have it because I am satisfied of its correctness. No: it is the inherited background against which I distinguish between true and false.”

Ludwig Wittgenstein (On Certainty)

Wittgenstein sounding like Heidegger, there.

Literally, then, fact-checkers or GROK (et al) are granting their Imprimatur — or Nihil Obstat (nothing stands in the way)– the license for truth. That nothing stated contains moral error, or doctrinal error. (now referred to as ‘misinformation’). The public today reflexively refer to these entities (one is a machine for fuck sake) to find alignment with what is being stated as ‘the truth’, the received facts of the matter. The reality is that these fact checkers are nothing of the sort (checkers of fact) and certainly legacy media has a long sordid history of dishonesty. But this leads to the more important part of this, and that has to with authority. But before that is a question pertaining to trust. The media lies all the time. There is ample proof of this. And yet many (smart people often) who know the media lie, will still consult the ‘official’ legacy media version. Its not that they ‘trust’ it but rather that they want to know the ‘official’ version the better to present their own measured and mature response. To question official versions is a heretical position, it is unseemly, it is, even if all agree that its true, a dangerous way to think. The world around them is not to be understood but to be incorporated into their own psychological brand. Belief retreats behind the encyclicals of the CIA or Zukerberg or the state department. And the actual authority of these positions, the official news, legacy media news or White House Press briefings; all these are like apostolic exhortations from the Vatican. But minus even reflex belief.

Mike Francis

The story of Covid was a perfect example of divine teaching — ‘trust the science’ (meaningless incantation) and parse guilt and shame as seems fit, by a thoroughly corrupt government and by corrupt health NGOs. But this is heresy, to question ‘science’. And it absolutely didnt matter that it wasn’t science. This was about something else. Nobody thought Covid was that dangerous. A few people ´perhaps, but the fear in the air was about the lockdowns. About government overreach. And at such times it is best to clutch your catechism and recite the Church teachings. Then attend Church (wear masks in public) and pray constantly (get boosters I guess). You get the idea. This was about obedience. Obedience as moral instruction and one side bar that fascinates me here is that the bourgeois left in the US and EU tend toward a demand that ‘art’ and ‘culture’ be morally instructive. Moral instruction is a lot like ‘but what do we DO?’ Its a strange mark of privilege.

There were, I think, during the pandemic, memory traces, elements buried deep in the reptile brain that connect to the Black Death and true plagues, that prowled the dark streets of Europe in the 1340s, where up to 40% of the population died; that experience lives on, in our cells, somehow. We access these memories (but more than memories, these are emotional memories, physiological memories) involuntarily, during times of stress. Somehow during Covid we remembered. And someday there will be a reckoning for those who in too cavalier a manner trifled with the lives of the elderly, and eventually with everyone, pushing a fake vaccine; and in too selfish a way imposed suffering across the countries of the world. And for that they will find some kind of inner circle of hell waiting for them. Perhaps something like the 6th circle, reserved for heresy. Eternity buried in flaming crypts.

Late in life, Wittgenstein made notes in preparation for a forward to Culture and Value, when its publication was suggested.

“I realize then that the disappearance of a culture does not signify the disappearance of human value, but simply of certain means of expressing this value, yet the fact remains that I have no sympathy for the current of European civilization and do not understand its goals, if it has any. So I am really writing for friends who are scattered throughout the corners of the globe.”

Ludwig Wittgenstein (Notes for a Preface, Culture and Value)

Sadaharu Horio

This is the appearance of the black doorway. I wrote before (and discussed in last workshop I did in LA, a few years back) that myself and other theatre artists I know are much like those desert fathers living out in the wilderness, in caves, protecting the ancient tomes of culture. At least as we know it.

So, there is an issue centred around the assault of lies and deceit. And this is tied into a loss of community, and of this epidemic (it seems) of loneliness. Who do we trust? And what does trust mean? Wittgenstein’s last book, On Certainty (like all his books after his first, it was not published in his lifetime) is if not the most profound, the most relevant to contemporary life. And there are volumes and volumes devoted to this small book, so for the purposes of this post I want to try to touch on his ideas about trust. And even this is not easy to do (in the context of a blog post). Now, much of the discussion centred around On Certainty (the book) involves two parallel streams: one is propositional or conceptual and one is linguistic.

“There seems to be in belief-in something more than a purely cognitive phenomenon – something unparaphrasable.”

Danièle Moyal-Sharrock (Understanding Wittgenstein’s On Certainty)

But the really interesting part of this is:

“Trusting is not a merely cognitive attitude’ (1969).To put the same point in another way, the proposed reduction leaves out the ‘warmth’ which is a characteristic feature of evaluative belief-in. Evaluative belief-in is a ‘pro-attitude’. One is ‘for’ the person, thing, policy, etc. in whom or in which one believes. There is something more than assenting or being disposed to assent to a proposition, no matter what concepts the proposition contains. That much-neglected aspect of human nature which used to be called ‘the heart’ enters into evaluative belief-in. Trusting is an affective attitude. We might even say that it is in some degree an affectionate one.”

H. H. Price (Belief, 1969)

Kevin Mulligan says that to ‘believe-in’ is always connected to believing it or them to be valuable.

Lois Dodd

“And if (as Price says above) we can believe in statistics, we can believe in rules of grammar, or indeed in grammar. Inasmuch as we can legitimately speak of believing in a method, there is no reason why we cannot believe in the method that underpins our language-games. And yet it cannot be said that an evaluative stance towards grammar is necessary to our believing in grammar. Indeed, we are often altogether unaware that we are making use of a method when we are using language, and even if we were, it can hardly be said that we have a pro-attitude or any evaluative attitude at all towards either that method or its components (rules of grammar) or axiological belief about these. So can we still speak here of belief-in? It is the essential and irreducible presence of trust which, on Price’s account, prevents belief-in from being reducible to belief-that.”

Danièle Moyal-Sharrock (Ibid)

What is so daunting in Wittgenstein is that everything he writes, everything he asks is immediately turned back on itself, at least momentarily, because he doesn’t *trust* language. Or how we use it, or how he uses it, and his entire ‘language games’ edifice is constantly being modified. Much like his one architectural venture, the house he designed for his sister, where he modified the drawings for the radiator countless times over six months (or a year in some versions).

“…to speak of trust is to speak of a fundamental attitude of one person towards others, an attitude which, unlike reliance, is not to be explained, or assessed, by an appeal to reasons. It is rather, because we have such a fundamental readiness to accept what we are taught by others that we can come to develop an understanding of reasons. The attempt to account for the role of trust in human relations as a matter of the accepting of statements … suffers from a cognitive and intellectual bias. Believing what others say is a refinement of other, more basic forms of trust. Only in a context constituted by trust, we might say, do truth and the making of statements have a place. We must begin by trying to understand the nature of trust as a primitive reaction.”

Lars Hertzberg (On the Attitude of Trust)

Think again of the friends who insist on reading what The Guardian says about Burkina Faso or Macron’s coke. Trust cannot finally be separated from Freud, either. And I maintain Wittgenstein would agree. Though he wrote few things about psychoanalysis, and those were cryptic and abstruse. (interesting article on Wittgenstein and T.E. Lawrence https://www.thearticle.com/unicorns-in-a-stable-t-e-lawrence-and-ludwig-wittgenstein)

César Galicia

“Annette Baier speaks of a ‘primitive and basic trust’, or ‘ur-confidence’ (1986). She contrasts ‘intentional trusting’, which requires awareness of one’s confidence, with ‘unself-conscious’ trust, the latter being paradigmatic in infants. Indeed, ‘infant trust’ is described as a kind of ‘innate’, ‘automatic and unconscious trust’ (1986). Baier elsewhere calls trust a ‘feeling’ (1994), as also a ‘mental phenomenon’, but remarks that, like all mental phenomena, it eludes classification into either the ‘cognitive’, ‘the affective’, and the ‘conative’: ‘Trust, if it is any of these, she writes, is all three.”

Danièle Moyal-Sharrock (Ibid)

But there is also a sense of the posthumous or retrospective to *trust*. And this is very telling if we can posit that our culture has suffered an enormous loss of trust altogether. Moyal-Sharrock notes that we are usually unaware of our trust. It is, in that sense, primitive. Ontologically primitive. And again Freud looms in the background.

“…our trust in others frequently shows in the very fact that we are unaware of our own trust. And on the other hand, if people are very conscious about the fact that they trust one another, or keep talking of it, that might justify doubts as to whether there is much trust between them in the first place. It seems that it is exactly unself-conscious cases that must be analysed … if we are to see how trust enters our lives.”

Olli Lagerspetz (The Notion of Trust in Philosophical Psychology)

Now, behind all this, or perhaps alongside it, is the Freudian/Marxist understanding of history, both individual and collective.

“By “social rationalization” Adorno, Horkheimer, and Marcuse mean the following phenomena: the apparatus of administrative and political domination extends into all spheres of social life. This extension of domination is accomplished through the ever more

efficient and predictable organizational techniques developed by institutions like the factory, army, the bureaucracy, the schools and the culture industry. The efficiency and predictability of these new organizational techniques are made possible by the application of science and technology, not only to the domination of external nature, but to the control of interpersonal relations and the manipulation of internal nature as well.”

Sylvia Benhabib (Critique of Instrumental Reason)

Science, or scientific thinking became the dominant form of rationality for western society. So a language game was to be understood in the light of what ‘game’ has come to mean. These words change. Trust-in, means trust in the organizational infrastructure of advanced capitalism. But also in the organizing principles of the Oedipal narrative. And they influence each other.

“…the attempt to remove error manifests itself in the way the precision of theory opposes the actuality of the built material. Does the precision of explanatory theory cause inadequate descriptive veracity? Philosopher Nancy Cartwright answers yes: ‘Fundamental equations are meant to explain, and paradoxically enough the cost of the explanatory power is descriptive adequacy. Really explanatory laws of the sort found in theoretical physics do not state the truth.’ An ideological commitment to science, precision and predictability comes at the cost of truth and functionality.”

Richard Marshall (review of Francesca Hughes, The Architecture of Error: Matter, Measure, and the Misadventures of Precision, 3AM Magazine)

Siegfried Zademack

“One cannot make experiments if there are not some things that one does not doubt. But that does not mean that one takes certain presuppositions on trust. When I write a letter and post it, I take it for granted that it will arrive – I expect this. “

Ludwig Wittgenstein (On Certainty)

But really, this is a different meaning of ‘trust’. But even it carries with it a certain nostalgia.

“Fascism is the extension of this suppression. Instead of forming an individual pathology, perversion indicates the inhumane instrumentalist roots of capitalist industrialism. Fascism constitutes the annexe of the irrational and self-destructive bourgeois culture.”

Antonio Vadolas (The Perversions of Fascism)

Fascism is the endgame for a turn in rationality that began before the Roman Empire, even. Fascism (and sadism) is the cultural expression, the political expression of the exchange principle. And it is the expression of a loss of trust. But there is another aspect to this and it inches into phenomenology.

“…primary trust is not a conclusion of reflection, but a direct taking-hold.”

Danièle Moyal-Sharrock (Ibid)

This is exactly the spot at which the central problem in all this is reached. For what does ‘taking hold’ mean? It means mostly nothing, as Wittgenstein would be the first to tell you. What was referred to as ‘ontological primitivism’ is reached here, too. And this is Heidegger’s argument, too, and largely Adorno’s and Freud’s (Das ding). Trust is not a conclusion, that is correct. It is not a part of an equation; but it IS something that is connected to history. But we had better figure out what is meant by history.

“The adaptation of clinical Freudianism proves awkward at best precisely because the fundamental psychoanalytic inspiration of the Frankfurt School derives, not from diagnostic texts, but rather from Civilization, with its eschatological vision of an irreversible link between development…and ever-increasing instinctual renunciation and misery.”

Fredric Jameson (Jacques Lacan: Critical Evaluations in Cultural Theory, Volume III)

Trevor Young

“Why is it that the more we cornered material error, the more we feared it?”

Francesca Hughes (Architecture of Error)

The unrepresentable, unsayable ‘thing’ — this ineffable space, unassimilable space that is the crossroads (Kierkegaard) where civilzation turns (sic) away and turns toward a compensatory rationality — which is then somehow always lacking immediacy. For Lacan it is lack itself. For Freud it is the desire for the Mother, but as this is only retroactively analysed, for the infant is pre-linguistic, there is this quality of the ‘Posthumous’ — the occurring after one’s death but only symbolically. Freud never fully articulated this desire/lack (or absence), though Melanie Klein probed it in the context of the death drive. Everything is tied into some kind of early (infantile) experience of ‘missing’ — the missed appointment (Lacan), and the question here is how do we come to ‘trust’, this idea that is referred to as adjacent to ‘warmth’. Trust is retrospective. Much like the legacy of early infantile experiences (sic) of lack. And why do *we* turn away? Why was there a ‘turning away’?

“There are, indeed, things that cannot be put into words. They make themselves manifest. They are what is mystical.”

Ludwig Wittgenstein (Tractatus)

One is left with mostly metaphoric descriptions like ‘taking hold’. Primary trust is an unconscious desire for a return. Bachelard said nostalgia was the memory of the lost warmth of the Nest. (I paraphrase). But the nest is ‘home’. That art and culture are inextricably tied to homesickness and exile has been discussed on this blog numerous times. Art always contains something, some trace or illusive memory fragment that is linked to the guilt of having left home to begin with. But, one is made aware of trust only when it is lost. (I really trusted her etc). So loss is baked into this mental structure. And it begs questions about how children learn the meaning of a word like ‘trust’. Guilt is related to our having, at some point, turned away from home. And the irony is that one HAS to turn away from home. To stay is its own pathology, and it deserves mention that today people continue to live in their parent’s homes for much longer periods than a hundred years ago. A third more, in fact. A third more live a third longer — with Mom and Dad. The pandemic played a huge part in all this, as have rental prices. The crushing of Unions and the advertising industry, the onset of Madison Avenue and the active discouragement to strive for autonomy.

Wittgenstein / Stoneborough House. Designed by Wittgenstein and Paul Engelmann. Vienna. 1925.

Rush Rees, a close friend and colleague of Wittgenstein, summarized the philosophy of his friend as the the search for an answer to the question: ‘what does it mean to say something’? Other readers who studied with Wittgenstein suggested (with a hint of sarcasm) the title ‘what does it mean to say anything at all’? I like that one. For that is, really, the question. I could imagine chapter headings such as ‘asking’, ‘not asking’, ‘not answering’, and so on. What makes Wittgenstein so singular is that he is never writing or teaching as an academic. He is trying, rather, to probe the meaning of existence. Its just that he thinks that meaning might well be found in breaking down how humans use language and how it got it be this way.

But Wittgenstein was surrounded by and worked in a milieu of positivism. One cannot shake the feeling that he himself was doing something very different from the positivists. By the time of On Certainty (which was never planned a book but was rather a collection of teaching notes and random thoughts) Wittgenstein was almost buddhist in his rejection of normal logic — and often when I read his last work I am reminded of Kafka’s aphorisms.

“Positivism internalises the constraints exercised upon thought by a totally socialized society in order that thought shall function in society. It internalises these constraints so that they become an intellectual outlook. Positivism is the puritanism of knowledge. What puritanism achieves in the moral sphere is, under positivism, sublimated to the norms of knowledge.”

Theodor Adorno (The Positivist Dispute in German Sociology)

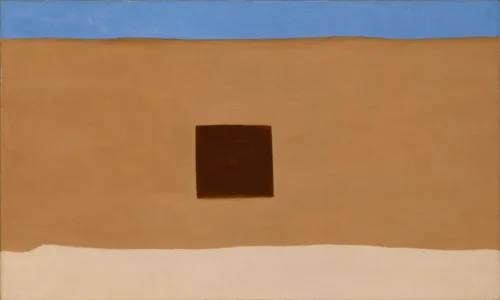

Geoorgia O’Keefe

Alain Badiou, with whom I have a rather contested private relationship, emerges as one of the better readers of Wittgenstein.

“The conditions of philosophy, i.e., the truths to which it bears witness, are always contemporary to it. It is in the confusion of their own time that philosophers construct new concepts, and they cannot diminish their alertness, be content with what is already there, or contribute to maintaining the status quo, without at the same time falling prey to the worst possible risk for the fate of their discipline: its absorption or incorporation into academic knowledge.{ } To tell the truth, as my readers moreover will be able to see for themselves, I do not really like this later book {Philosophical Investigations}, and even less so, I must say, what it has become, to wit: the involuntary, undeserved guarantee of Anglo-American grammarian philosophy—that twentieth-century form of scholasticism, as impressive for its institutional force as it is contrary to everything that Wittgenstein the mystic, the aesthete, the Stalinist of spirituality, could have desired.”

Alain Badiou (Wittgenstein’s Antiphilosophy)

It is telling that so many of the greatest books, both fiction and philosophy, of the 20th century, the century of modernism, were unfinished. It is an allegorical fact. The first generation brought up on TV saw the normalizing of interruption, which is another version of unfinished.

Most of the critical writing on Wittgenstein is done by positivists. When I read Donald Davidson or Norman Malcolm, for example, or Danièle Moyal-Sharrock (who I think is a very cogent reader of Wittgenstein up to a point) I find I do not recognize a lot of what they say about Wittgenstein. Their work is useful, and they have a lot of knowledge about Wittgenstein, and thinkers like Moore or Russell, neither of whose work I know very well, to be honest, but they are still writing from within the academy.

“…it is not a question of substituting art for philosophy either. It is a question of bringing into scientific and propositional activity the principle of a kind of clarity whose (mystical) element is beyond this activity and the real paradigm of which is art. It is thus a question of firmly establishing the laws of the sayable (of the thinkable), in order for the unsayable (the unthinkable, which is ultimately given only in the form of art) to be situated as the “upper limit” of the sayable itself:”

Alain Badiou (Ibid)

“I think I summed up my attitude to philosophy when I said: philosophy ought really to be written only as a poetic composition.”

Ludwig Wittgenstein (quoted by Ray Monk, via Badiou)

Zev Tiefenbach, photography.

What separates Wittgenstein from his contemporaries (at Oxford, etc) is his deep distrust of systems. And that he was always conducting something like an autopsy of how people speak. That ‘truth’ (more on that below) is found not so much in language but in speech, in the human and his development of speech.

“Indeed, insofar as a proposition is true only inasmuch as it describes a state that “happens,” or a state of the world, and insofar as the world, as collection of events, is given over to contingency, there is no other means to verify that an elementary proposition is true except to compare it with reality, with the observable “it has happened”: “In order to tell whether a picture is true or false we must compare it with reality.”

Alain Badiou (Ibid)

The last line of my play The Shaper (1985) is “something has happened”. I was reminded of this as I read Badiou here, because ‘something’ suggests the speaker is not sure ‘what’ happened, only that it happened, or not ‘it’, but something. There was a happening. And this is important. Understanding that the ‘not knowing’ part is as important as the verifying comparison –whether true or false. But the cascading of questions follows; what does true mean? What does false mean? What do we mean by ‘mean’?

Wittgenstein is creating a climate for discourse. It may be the most important thing he did.

Allow me a longer quote from D.Z. Phillips, who edited a book by Rush Rhees, an excellent writer himself;

“When Wittgenstein took up philosophy again eight years after the Tractatus, he placed great emphasis on the verification of a proposition. He thought this emphasis became unprofitable once the Positivists had turned it into a rigid thesis. What Wittgenstein found important in the notion is that verification takes time. The meaning of a word or a proposition is not given to us all at once. We must look for it in the function they have in the language-game to which they belong. These functions vary. We are confronted by a vast array of them. This emphasis on the function of words and propositions is prominent in Part One of the Investigations, and there are clear parallels in Part Two. But in Part Two, Rhees argues, there is also a corrective to this view of language. Moreover, it is a corrective which has to do with Wittgenstein’s claim that a genre picture says itself. It is easy to misunderstand the contrast Wittgenstein is drawing. Wittgenstein is not saying that the meaning of the genre picture is given all at once. His emphasis on verification was meant to combat THAT view. Here, the place occupied by ‘function’ in that context, is now occupied by ‘culture’. One could not appreciate a great painting if that were the only painting one had seen. To see why a painting is a profound treatment of its subject one would have to compare it with other paintings of lesser significance. I do not mean, of course, that the comparison has to be made on the occasion of seeing the great painting, though that might occur. “

D.Z. Phillips (Wittgenstein On Certainty — There, Like Our Life)

Richard Combes

This is a great quote. Function replaced by culture. This is at the heart of what Wittgenstein is doing. Culture, an atmosphere or climate for thinking. Somewhere Wittgenstein once asked ‘how is it we judge which is my right hand and which is my left’? We may have learned that we are ‘right handed’ and hence know right is the hand I use to write etc. But this does not answer the question. This sort of ‘knowledge’ occupied Wittgenstein a great deal over the years. Subjects like colour blindness (he maintained some people suffered ‘aspect blindness’) or other imperfections to ‘knowing’. Something has happened. Wittgenstein explained language games by saying ‘they are neither reasonable nor unreasonable; they are just there, like our life’. This became the title for Phillips book. But one can quickly see that Wittgenstein was not a positivist. And in fact the mystical part of him is tied into how unsystematic he took reality to be, and how things, all things, changed.

Lacan once said ‘there is no other to the other.’

By the by, there is apparently only one photo ever taken of Rush Rhees.

Rush Rhees

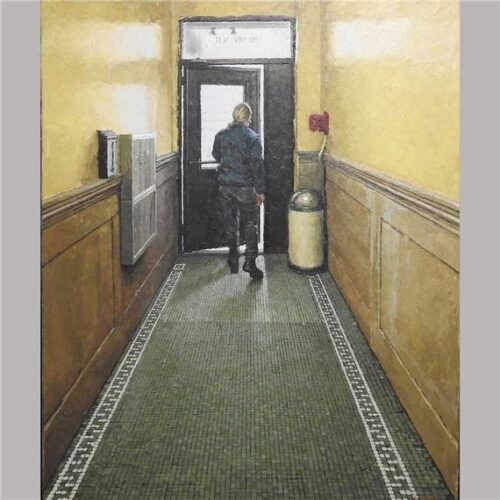

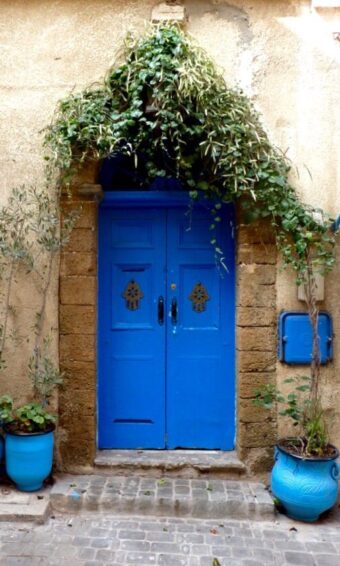

Door in El Jadida, Morocco. (photographer unknown).

“It is Wittgenstein’s later doctrine that outside human thought and speech there are no independent, objective points of support, and meaning and necessity are preserved only in the linguistic processes which embody them.”

David Pears (Wittgenstein)

Now, much Buddhist thought from a variety of schools, discuss the *ineffable* frequently. Jay L. Garfield writes in the introduction to a book on the Tao (dao)..

“the Daodejing and the Zhuangzi. The Daodejing is traditionally attributed to a figure called Laozi 老子—the “Old Master”—who is supposed to have lived between the 6th and 4th centuries BCE, but the text we have is an amalgam that draws from several sources (Chan 1963; Graham 1981; Hansen 1992). The author of the eponyomous Zhuangzi is traditionally dated to the 4th century BCE, but the thirty-three-chapter text in circulation today, edited by Guo Xiang 郭象 (d. 312), is based on a compilation that dates to the 2nd century BCE.”

Quoting Wang Bi: “The Dao that can be rendered in language and the name [ming] that can be given it point to a thing/matter [shi] or reproduce a form [xing], neither of which is it in its constancy [chang]. This is why it can neither be rendered in language nor given a name.”

and then Garfield’s gloss on it;

“We have now seen that, at least according to Wang Bi’s interpretation, the Dao, important as it is—indeed, fundamentally important—is ineffable. Any category can apply to only part of reality, and any attempt to apply it to the whole would turn it into something that it is not. There is an obvious knot here. The Dao is ineffable. Yet the Laozi says a lot about it, as we have seen, including that it is ineffable. Indeed, one cannot explain why it is ineffable, as Wang Bi does, without talking about it. And when we say that something is ineffable, we are talking about that thing, and not something else.(To talk about something else would be to change thesubject!) Now, to talk about something may not be to say that it is effable; but doing so shows that it is. So the Dao is ineffable, by claim, and effable, in virtue of the fact that it is claimed to be ineffable. One does not have to be a genius to note this point. It is clear to even a casual thinker, and Wang Bi is much more than that.”

Jay L. Garfield, Graham Priest (What Can’t Be Said)

Anne Carney Raines

In one my recent posts I talked about liminal space. In architecture. And there is a mysterious appeal to these spaces. I think this appeal is related to the lack of purpose in such spaces. These are often zones of transition or transit. Psychological transition, too. Also connective spaces, often enough. Spaces of allegory. They are experienced as ’empty’, even if usually they are not. The liminal space is like a training wheels version of real emptiness. Precursor transcendental. In much Buddhist practice the ineffable is that which cannot be expressed. Emptiness, though, is highly complex and different schools of Buddhism have different ideas about a transcendental reality, a dissolving of duality. When Wittgenstein says..’its just there, like our life’, he sounds very much like a Buddhist teacher.

When Freud or Lacan or even Heidegger refer back to something, trace back to infant consciousness (both individual and collective) they arrive at this point (das ding, or a thousand other terms) — this absence, this missed something. And man’s ‘fall’ for many of these thinkers is this turning away — to turn away and begin the long long march of civilization. We begin to name things, to create grammar and discourse and the world. But what is key is that this absence is an ‘absence’. A lack, and this is the beginning of subjectivity. And that from which we turned away is never forgotten.

Art is one glimpse of this missed appointment, as it were. Art allows a fleeting glimpse of this ‘space’, this ‘something’ — and it is this, later, often what we experience as uncanny. The ‘great silence’ of Carthusian monasteries is a patient long waiting for subjectivity to empty itself of a lifetime of noise and ‘furniture’. This has always been what I found in theatre — the endless repetition of rehearsal, the practice, the reciting of memorized speech — not our own speech —(why ‘improv’ never works and is in fact an affront to the idea of theatre) — but just recitation, performed through the long learned process of performance, unconsciously. And then the lights come on or the curtain raises, and something has left the theatre and the play must pursue it. Never to catch it, for all this is impossible. And only within the impossible is some kind of reintroduction to the absence found. Even if only for a moment.

Toshimi Kitano

This is why so many great works are unfinished. Great art cannot complete itself, for it then nullifies itself. But this is a very complex dialectic, I think. Some work that is completed finds strategies to embed that quality of unfinished or liminality.

Jay Garfield has a long analysis comparing several schools of Buddhism (Garfield was David Foster Wallace’s undergraduate honors thesis advisor at Hampshire College, overseeing Wallace’s one slim volume of philosophy.) But I trust him on Buddhism in spite of this.

Below from a history and comparison of Madhyamaka and Yogacara Buddhism.

“Even the thought, ‘All this is appearance only’ involves an object,” etc. The word “object” is used to indicate that though he says he is without an external object there is grasping and labelling. The grasping and labeling is precisely grasping on to the content “all this is appearance only,” to all this, and to the concept appearance only. And the medium through which these are grasped by the mind is conceptual and hence, for Vasubandhu and Sthiramati, adequate only to the conventional, and in the end, entirely deceptive.

When no object is apprehended

By consciousness,

Then grounded in appearance-only

With no object there is no grasping subject.

Consciousness directed on the ultimate, by contrast, has no object and involves no apperceptive subjective consciousness, no conceptual content or medium, and hence nothing expressible. When consciousness does not objectify these as external to mind; doesn’t see them; doesn’t grasp them; doesn’t posit them, then it perfectly sees the pure meaning. At that time, no longer like a blind person, having eliminated the grasping of consciousness, it is grounded in the nature of mind itself. This is because “With no object there is no grasping subject.” Where there is an object, there is a grasper. Where there is no object, there is none. Where there is no object, there is a subjectless realisation, not just an objectless one. So, conceiving of neither the constructed object nor the constructor of the object, the equanimous transcendental wisdom is attained. The remnants of subject and object are eliminated and the mind becomes grounded in its own nature. When the mind is grounded in mind only itself, what is it like?

Then with no mind and no object

With supramundane knowledge,

It is transformation of the basis,

And the end of the two adversities.

This verse is taken, of course, by Sthiramati, to be an answer to the question we have all been dying to ask, “What is it like?” Well, what is it like? Neither Vasubandhu nor Sthiramati, nor Vinitadeva can say. And the reason, of course, is that at this point we have transcended the realm of expression. But, as we shall see, while these Yogacara philosophers, like their Madhyamaka interlocutors, distinguish an inexpressible ultimate from a characterizable conventional, the ultimate so characterized is different, the apprehension is of a different epistemic order, and the explanation of silence differs as well.”

Jay L. Garfield (Empty Words: Buddhist Philosophy and Cross-Cultural Interpretation)

At the end of this lecture, Garfield writes … ” Madhyamaka silence reflects the impossibility of expressing the truth about the conventional world. Yogacara silence reflects the intuition that there is none.”

I had a Zen teacher (once upon a time) who said…’when you are studying and practicing you look out at the mountains and see only mountains. As you become more advanced, a bodhisattva, the mountains become something more and mysterious and wondrous. When you reach enlightenment, you look out at the mountains and again see only mountains.’

To donate to this blog (and the Aesthetic Resistance podcasts) use the paypal buttom at the top of the page.

Speak Your Mind