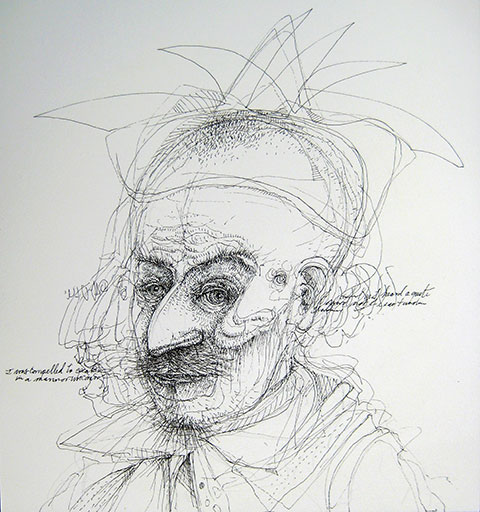

Jaco Putker

” Gandhi was also convinced that Hitler had some sort of twin brother. But this was not Stalin, who, still in September 1946, was considered by the Indian leader to be a “great man” at the top of a “great people.” No, Hitler’s twin brother was ultimately Churchill, at least judging from two interviews that Gandhi had given in April 1941 and April 1946 respectively: “I assert that in India we have Hitlerian rule, however disguised it may be in softer terms.” And further: “Hitler was Great Britain’s sin.’ Hitler is only an answer to British imperialism.”

Domenico Losurdo (Stalin and Hitler: Twin Brothers or Mortal Enemies?)

“ …a good book is a good action. It has more than the force of good example. And if the moralist will say that it has less merit—let him. Indeed we are not writing for the salvation of our own souls. ‘A man should not be tame’ says the Spanish proverb, and I would say: An author is not a monk. Yet a man who puts forth the secret of his imagination to the world accomplishes, as it were, a religious rite.”

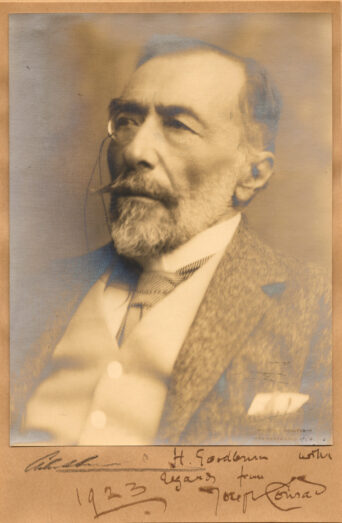

Joseph Conrad (Letter to E. V. Lucas on October 6, 1908)

“Conrad thought that when one wrote, even in a realistic way, about the world, one was writing a fantastic story because the world itself is fantastic and unfathomable and mysterious. { } I talked to Bioy Casares, who also writes fantastic stories—very, very fine stories—and he said, “I think Conrad is right. Really, nobody knows whether the world is realistic or fantastic, that is to say, whether the world is a natural process or whether it is a kind of dream, a dream that we may or may not share with others.”

Jorge Luis Borges (Interviews)

“…the more reflection gets the upper hand and thus makes people indolent, the more dangerous ressentiment becomes, because it no longer has sufficient character to make it conscious of its significance.”

Søren Kierkegaard (The Present Age)

“I believe more and more,” writes Van Gogh, “that God must not be judged on this earth. It is one of His sketches that has turned out badly.”

Albert Camus (The Rebel)

The culture of the US is one in which this culture affords itself very little real importance. American culture both promotes itself as special (in some sense, however vague) but also not to be taken seriously. And there has developed (it was always there to some degree) a very instrumental and materialist notion of ‘what’ culture does. I was thinking of Edward Said’s book on Joseph Conrad. A book that has always elicited a decided ambivalence even for fans of Said. Part of this is the simplistic reputation that Conrad has come to hold for those who ‘know’ of him but don’t read him (well, nobody reads him, for all intents and purposes). But for me (and I should note my father adored Conrad, it was without qualification his favorite author) Conrad has always held a special place though I realize I have not written much about him. Still, he is always there, and I think there are two reasons for this. The first is that Conrad wrote ‘adventure’ stories but he took that idea seriously. And perhaps in a sense that is what I have always tried to do. And secondly, Conrad saw literature (and art) linked to decisions in life — Giles Foden wrote of Conrad : “At the age of 17, in October 1874, he left Poland, travelling by train to Marseille, making what he later described as a “standing jump out of his racial surroundings and association”. This idea of the “jump” – the radical existentialist step – is central to Lord Jim and many of Conrad’s other novels and short stories. In Lord Jim, the hero leaps from a ship full of Muslim pilgrims, which he believes to be sinking. The act dogs him for ever, but the question of whether he is a coward is not simply answered. It relates to the whole book and other books, too – the idealistic Coral Island-style yarns that made Jim take ship in the first place.”

(The Moral Agent, The Guardian, 2007)

Conrad is quintessentially modern in theme and in style. The ‘jump’, for those who take it, is irresistible. Foden suggests Camus is a close relative of Conrad and I can buy that. Conrad, however, is the greater writer probably, if only because of his monumental difficulty. But the comparison is apt, regardless. The fact that Conrad’s fiction (and Camus, really) are genre fiction is the actual lesson.

Joseph Conrad (signed photo 1923, London)

“Even in the best of Conrad’s fiction there is very often a distracting surface of overrhetorical, melodramatic prose that critics like F. R. Leavis, sensitive to the precise and most efficient use of language, have severely disparaged. Yet it is not enough, I think, to criticize these imprecisions as the effusions of a writer calling attention to himself. On the contrary, Conrad was hiding himself within rhetoric, using it for his personal needs without considering the niceties of tone and style that later writers have wished he had had. He was a self-conscious foreigner writing of obscure experiences in an alien language, and he was only too aware of this.”

Edward W. Said (Joseph Conrad and the Fiction of Autobiography)

Genre fiction, and themes of exile. Of forever ‘not’ being home. Of forever being unable to go home. And for reasons that are myriad and complex and must be written about. The moral intensity of Conrad is the understanding that with that ‘jump’ comes something more than just a responsibility, there comes a duty. There is also, within Conrad (and I suppose Camus, too, but far less) a rejection of bourgeois values — or perhaps it is better to say a refusal of bourgeois culture and vision. This was the tension within Camus (no such tension is found in Genet, say, and certainly not Conrad). One cannot fake that refusal. This is really the litmus test for writers of the last century. And one of the things lost (of which I keep writing about) is exactly this litmus test. In later life Conrad was to be acquainted with both H.G. Wells and Henry James, the two most famous literary figures of the age. Both knew (and acknowledged) Conrad’s genius but both were deeply envious of it, too. Both were sure not to ‘like’ the man. Ford Maddox Ford did become a good friend. But Conrad’s art is difficult to write about, and often one will read about the ‘complexity’ of the settings and points of view. And while true to a degree, the same can be said of any relatively important writer. Conrad wrote crime stories. Much like Patricia Highsmith did a half century later. But he endowed them with Shakespearean depth. Lord Jim is Hamlet. Victory is The Tempest. Heart of Darkness is Macbeth, well, sort of. But perhaps Conrad’s greatest book is Nostromo. (also regarded as the most impossibly difficult to read). Nostromo is Treasure of Sierra Madre. But it also Blood Meridian. It is parts of Moby Dick, too. And this is because the structure of all great American literature is always a single uninterrupted scream of anguish. It is Red Harvest and it is An American Tragedy. Val Lewton’s film The Ghost Ship is The Shadow Line…perhaps consciously. But Heart of Darkness and Nostromo probably stand as the most Conradian of fictions. Frederic Jameson (noted by Foden) said Conrad was “floating uncertainly between Proust and Robert Louis Stevenson”. And Stevenson himself floats uncomfortably between literature and boy’s adventure stories.

And to understand this cultural dilution is to understand this legacy is NOT American Psycho. Iceberg Slim and John Rechy certainly brushed up alongside Conrad. Flannery O’Connor, too. The detective novel brought into sharp focus the tendencies already out there in the scorched earth psychology of Puritanism. Conrad is closer to Jim Thompson than he is to Henry James. The Secret Agent is second cousin to Dostoyevsky and Kafka, but by way of A High Wind in Jamaica and Dr. Mabuse . Moby Dick and The Confidence Man are both crime novels. It is not uninteresting that Borges thought Conrad the greatest novelist. But in spite of something like eight volumes of letters and several biographies, the man Joseph Conrad remains stubbornly opaque.

David Inshaw (1974)

And this in an indirect way brings me back to the poverty of contemporary culture. But this is a dialectical relationship one has today with culture. It is hard to get a sense if irony is possible anymore, or, in more puerile terms, just how ‘meta’ can things get? (See the new Jon Hamm series Your Friends and Neighbors. The show is, and Hamm is, recuperating Mad Men in some deleriously loopy way, but oddly one that works enough that I’ll keep watching. And this may well be, as Michael Hogen noted in the Guardian, because Hamm is actually very good at what he does, narrow though that palette might be). (now I’ve only seen three episodes so its hard to know how long this can be sustained). Apple already ordered a second season. Shows set against backdrops of extreme wealth tend to do well. Especially if they pretend to be scolding the rich but are really just admiring them.

There is nothing Shakespearean about Your Friends and Neighbors. The cultural memory goes back fifteen years, to the end of Mad Men.

But cutting across all of this is colonial history. And Said was, of course, a Palestinian. An Arab (though not a Muslim). And I think both Fanon and Said have, since their death, become something other than what they were in life. And I think its impossible not to revisit at least a few ideas from his book Orientalism. And, it is important to look at why Camus took the side of the French in Algeria so consistently.

Antonio Zanchi (Sisyphus, 1660)

The theme of exile is extraordinarily important to writers in the second half of the 20th century. But it is perhaps of less importance (or there is less awareness of it) in American writers. Earlier writers such as Melville and Twain were acutely aware of exile and home, of alienation and the destructive tendencies in U.S. racist systems. But by by mid century the sense was more inwardly focused and this accounts for the lack of political vision among many of them. Now, that lack was compensated for by other things: paranoia and the horrors of the Atomic age. From Dick and Pynchon to the last remnants of the Golden Age of American cinema, the nightmare did not abate. But still, a Camus, who for all his tortured political identity, saw the plague as one that ate up French and Algerian consciousness and history. Le Peste (The Plague) is a book that cannot be read with the normal presumptions.

“I would go so far as to say that because Camus’s most famous fiction incorporates, intransigently recapitulates, and in many ways depends on a massive French discourse on Algeria, one that belongs to the language of French imperial attitudes and geographical reference, his work is more, not less interesting. His clean style, the anguished moral dilemmas he lays bare, the harrowing personal fates of his characters, which he treats with such fineness and regulated irony—all these draw on and in fact revive the history of French domination in Algeria, with a circumspect precision and a remarkable lack of remorse or compassion.”

Edward Said (Culture and Imperialism)

Camus’ prose is pristine and (Barthes called it ‘white writing’ {écriture blanche}) self consciously so. I have always thought this a virtue and in fact the criticism against the Camus (in The Plague) is that the language lacks the concrete everydayness of a real occupation. But fascism as an idea feels accurately depicted by this transparent prose, a prose distant from daily speech. Yes the reader is being made aware of reading ‘literature’ but again, like Said, I rather think this appropriate. Fascism as an invisible infection that spreads silently like a pestilence, is an uncannily perceptive idea. Camus is a better version of Paul Bowles in some ways, though Bowles is a better version of Camus in others.

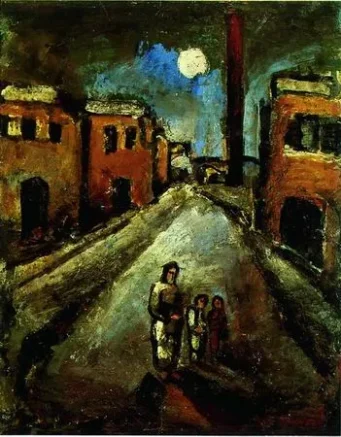

George Roualt (Christ in the Suburbs) 1920.

Modernism promised something, and Adorno spent agonizing years and volumes trying to articulate exactly what, but whatever it was the failure is what society is left with now. And that was going to be its fate . Modernist fiction was also going to exhaust the philistines out there. I am reminded constantly in much informal writing (for blogs often) that this anti-intellectualism of the age seeks to validate itself. The disenchantment of society has meant a specific kind of anti-intellectualism has taken hold and fixed itself terminally to the disillusioned dreaming, or half dreaming, of the educated bourgeoisie.

And here is a good time to return to Kierkegaard. To Kierkegaard even more than to Nietzsche perhaps. For Kierkegaard marked the shift to a modern form of inwardness. And Bartholomew Ryan has an interesting book on Kierkegaard’s influence on four disparate thinkers (Adorno, Schmitt, Lukács, and Benjamin). The relevant part here is that this modernist promise is something each of these thinkers wrestled with and also rejected. But Kierkegaard anticipated much of the dying lights of modernist promises.

Spencer Gore

“Of all tyrannies a people’s government is the most excruciating, the most spiritless, unconditionally the downfall of everything great and sublime […] A people’s government is the true picture of hell.”

Søren Kierkegaard (Pap.VIII I A 667, 1848)

“Rather, as Adorno wrote in one of his final formulations, it would be sacrifice that would become memory of nature as the expression of sacrifice: “All that art is capable of is to grieve for the sacrifice it makes and which it itself, in its powerlessness,is.’Kierkegaard: Construction of the Aesthetic’ was the first major philosophical study Adorno published; it appeared in bookstores on February 27,1933, the day that Hitler declared a national emergency and suspended the freedom of the press, making the transition from chancellor to dictator.References to Kierkegaard inevitably note this as ironic.There is nothing ironic about it: Kierkegaard is the study of the unconscious reversal of history into nature, Adorno’s first analysis of the dialectic of enlightenment. According to Adorno, sacrifice “occupies the innermost cell of his (Kierkegaard’s) thought.'”

Robert Hullot-Kentor (introduction to Kierkegaard by Adorno)

Now, this was Adorno’s first publication. His book on Freud and Kant and Aesthetics preceded it, but not was not published. No matter — one point (and Hullot Kentor is very good on this topic) is Adorno’s style. And since I am accused of digression (and all manner of other thing) I wanted to point out again how Adorno saw writing and thinking.

Adorno’s ideal of form was that “every sentence should be equally near the center- point. The parts refer to one another and complete one another by a principle of contrast. Topics develop without any schematized preparation.” This is what I tried to do in my way in theatre, it was, in a sense, how I directed, and it is certainly how I approach this blog-. And what is amazing is the amount of resistance I encounter (most recently with Upsalla University who refused to include my paper in an upcoming collection on AI. You might think a philosophy department would at least make a fucking effort to think outside the box. But no.).

Allen Jones (1966)

I digress. Adorno’s study of Kierkegaard is only now being given the attention it deserves. And there are probably several reasons for this neglect, but first is the fact that the Kierkegaard-industry has very particular models of the Kierkegaard they want promoted. And Adorno’s is not one of those models. For Adorno the subtitle is the critical factor here…’the construction of an aesthetic’. Kierkegaard’s radical inwardness is deeply unsettling, and it is part of how Adorno approaches the promise of aesthetic liberation, the promise of western society.

“[Images at a standstill] may be called dialectical images, to use Benjamin’s expression, whose compelling definition of ‘allegory’ also holds true for Kierkegaard’s allegorical intention taken as a figure of historical dialectic and mythical nature. According to this definition, ‘in allegory the observer is confronted with the facies hippocratica of history, as a petrified primordial landscape’ – In Kierkegaard nature is mythical as proto-history, cited in the image and concept of his historical moment.”

Theodor Adorno (Kierkegaard)

This is the latent Christian Adorno. He opens the book with a quote from Edgar Allen Poe describing the surviving of a maelstrom. Adorno writes “Inwardness is the historical prison of primordial human nature.” This is remarkably like Benjamin from his book on German tragic drama. It is also mysticism. It is the dialectic of Enlightenment appearing in an early form.

Master Bertram of Minden (High Alter of St Peter’s in Hamburg. 1380)

This is from Dialectic of Enlightenment… “Humans believe themselves free of fear when there is no longer anything unknown. This has determined the path of demythologisation, of enlightenment, which equates the living with the nonliving as had equated the nonliving with the living. Enlightenment is mythical fear radicalised.”

Kierkegaard is gateway drug for Freud, of course. He understood the questions of resentment and the relationship to power and guilt. But a very germane and essential core of the Enlightenment dialectic is the idea of knowing everything. That science ‘can’ know everything. For this raises a whole mountain of questions that start with what does it mean to ‘know’ something?

“…and the opening line of Adorno’s Kierkegaard reads: “Whenever one strives to grasp philosophical texts as poetry, one misses their truth content [Wahrheitgehalt].” This reflects Adorno’s lifelong dilemma shown in his desire to quote from Friedrich Schlegel to serve as a motto for Aesthetic Theory: “What is called the philosophy of art usually lacks one of two things: either the philosophy or the art.”

Bartholomew Ryan (Kierkegaard’s Indirect Politics)

That one can project forward to mid century fascism, and its resurgence today, is the disturbing truth of reading everyone from Kafka to Pinter, from Nietzsche to Kierkegaard. In fact Ryan has a telling footnote in his chapter on Heidegger:

“Heidegger, in Being and Time, uses many of the ideas and observations in Kierkegaard’s Two Ages:A Literary Review, and it could be easily argued that this had an enormous influence on Heidegger’s path towards membership of the Nazi Party. Two Ages:A Literary Review’s impact can be felt in Camus’ The Rebel, and Sartre’s trilogy novel Roads to Freedom and the major existentialist work Being and Nothingness, which all emphasise the ‘malaise of the age’. “

Bartholomew Ryan (Ibid)

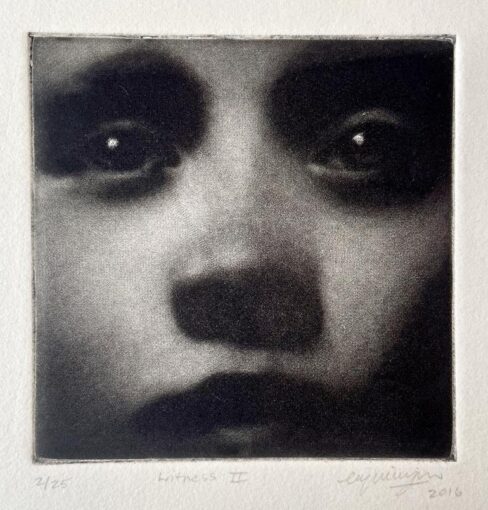

Camilla Engstrom

Camus essay The Rebel has been consigned to the dust bin of reactionary theory (by a certain brand of Marxist anyway). And yet to revisit it is to see the foreshadowing of fascism as a kind of return of the repressed. Camus’ essays feel much less reactionary today than they did forty years ago.

“Restraint is not the contrary of revolt. Revolt carries with it the very idea of restraint, and “moderation, born of rebellion, can only live by rebellion. It is a perpetual conflict, continually created and mastered by the intelligence.… Whatever we may do, excess will always keep its place in the heart of man, in the place where solitude is found. We all carry within us our places of exile, our crimes and our ravages. But our task is not to unleash them on the world; it is to fight them in ourselves and in others.”

Sir Herbert Read (introduction to English translation of Camus’ The Rebel)

“The American novel claims to find its unity in reducing man either to elementals or to his external reactions and to his behavior. It does not choose feelings or passions to give a detailed description of, such as we find in classic French novels. It rejects analysis and the search for a fundamental psychological motive that could explain and recapitulate the behavior of a character. This is why the unity of this novel form is only the unity of the flash of recognition. Its technique consists in describing men by their outside appearances, in their most casual actions, of reproducing, without comment, everything they say down to their repetitions, and finally by acting as if men were entirely defined by their daily automatisms. On this mechanical level men, in fact, seem exactly alike, which explains this peculiar universe in which all the characters appear interchangeable, even down to their physical peculiarities. This technique is called realistic only owing to a misapprehension. In addition to the fact that realism in art is, as we shall see, an incomprehensible idea, it is perfectly obvious that this fictitious world is not attempting a reproduction, pure and simple, of reality…{ } Novels of violence are also love stories, of which they have the formal conceits—in their own way, they edify.”

Albert Camus (The Rebel)

Daido Moriyama, photography.

Novels of violence are also love stories. All love stories are also about violence. But most importantly, all are about homesickeness. When Herbert Read says we all carry within our places of exile, he is right, of course but he would be more right if he said simply ‘places of exile’. That is the difference between the fascist (capitalist) and the revolutionary. *Our* place of exile is not really ours. Exile is not personal anyway. Odysseus’ exile is everyone’s exile.

“In the world of the spirit, all are invited, […] if it pertains to one single person it pertains to all.”

Søren Kierkegaard (Eighteen Upbuilding Discourses)

“The age of revolution is essentially passionate, and therefore it essentially has form […] The age of revolution is essentially passionate, and therefore essentially has culture. In other words, the tension and resilience of inner being are the measure of essential culture. “

Søren Kierkegaard (Two Ages: A Literary Review)

The year 1848 looms as pivotal — (Communist Manifesto is published), revolutions and instability are ushering in a new era.

“In the European context 1848 is symbolic, as its aftermath triggered both reactionism and further revolution with equal force. After the revolutions of 1848, the position of philosophy in the universities had become politically compromised, bowing in the direction of Königsberg. Peripheral parts of Europe were ripe for revolution, and it was a year that broke the spirit of cultures from which some never fully recovered. However, in Denmark a new national spirit was awakened from 1848. Even though conscription was obligatory only to the peasant, after 1848 many of the bourgeoisies volunteered. Additionally, in 1848 there was reaction to Marx and Engels’ revolutionary charter of the proletariat revolution. At Wittenberg, over the grave of Martin Luther, K. H. Wichern replied with a counter-revolutionary “Protestant Manifesto.”

Bartholomew Ryan (Ibid)

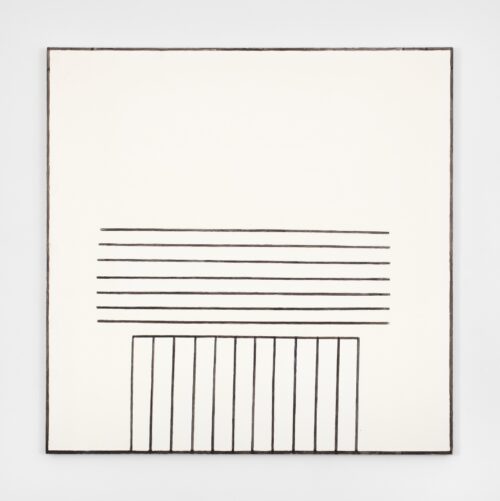

Dan Walsh

This was the year that began (at the least) the long foreshadowing of the 20th century (and now the 21st). Much would, a short while later, coalesce around Vienna — the city in which Freud, Hitler, Tito, Stalin, and Robert Musil, and Klimt, Schönberg, Alban Berg, and Stefan Zweig all lived. And Wittgenstein, who attended the same middle school as Hitler (they were born only six days apart). And as coincidences; Kierkegaard had the same birthday as Marx — only Marx was six years younger. But this later fin de siecle era was anticipated by the upheavals of 1848.

For Kierkegaard this was a year in which his thought found a metaphoric clarity. And the most indelible and widely used image was that of the *crossroads*. (Skillevei in Danish). And walking was, for Kierkegaard, something akin to prayer.

“The Skillevei can also be viewed as a reference to life and death, standing between death and the roaring charge of the masses, that new phenomenon or “spectre” which was on the move across Europe. The awareness and anticipation of death pushes one out into life, and the Skillevei of the individual and the mass provides this important distinction. Anti-Climacus writes in unabashedly rhetorical language to the reader: “no one asks what wrong you suffer, no one asks where it pains or how it pains, while the mob in its animal health tramples you in the dust”. The Skillevei implies a decision, a decision that may save the reader from the unthinking masses in transitional Europe. Anti-Climacus continues on the same page: “the invitation stands at the crossroad, where death distinguishes death from life.” The stakes have risen, and the Skillevei becomes a metaphor for the crossing of life and death. Kierkegaard’s two most important prototypes, Socrates and Christ, were both sentenced to death by the Law. Both died for the ‘Truth’, and the idea of the ‘progressive’ West was born from these two famous deaths: in philosophy with Plato’s Socratic dialogues and in Christianity with the four gospels. This is the West of Christianity and Athenian Greek Philosophy, and yet they began as marginal, revolutionary figures, as Kierkegaard reminds us. There is always the marginal that reveals pluralistic aspect of the West, and which inserts itself as the periphery, thorn and inspiration to the ‘progressive’ West, such as in the Celtic, Judaic, Nordic, Slavic, Muslim and Romani histories, among others.”

Bartholomew Ryan (Ibid)

Arnold Böcklin (self portrait with death, 1872)

In American gospel tinged blues, the story of the ‘crossroads’ was repeated in a dozen versions, usually including a deal with the Devil. The black church walked to its fate. In a curious side bar, the short story, The Devil and Daniel Webster was published in 1936 by Stephen Vincent Benet. In which the devil must argue the validity of his contract for the soul of a New Hampshire farmer against lawyer Daniel Webster. Among the jurors were Edward Teach (Blackbeard) and John Hathorne, who presided at the Salem Witch trials. But the story of the Devil Fiddler is heard throughout northern Europe in 1600s, and then in Quebec, Canada where a number of folk tales have Satan playing fiddle. There are stories, too, built around Norwegian folk traditions and a devil’s bribe. And often (as in the Washington Irving story, The Devil and Tom Walker) devil wagers on the outcome of a musical duel.

“To the earnestness of death belongs that remarkable capacity for awakening.”

Søren Kierkegaard (Works of Love)

Hullot-Kentor’s introduction to his translation of Adorno’s book Kierkegaard: Contruction of an Aesthetic, touches on a crucially significant aspect of Adorno’s thought altogether.

“…allegories are not symbols ‘(for the thought symbolised was nowhere expressed).’This, however, does not mean that they are Inexpressive; their expression, rather, is by way of nonexpression: the collapse of meaning into nature. In a talk Adorno gave just before the final revisions of Kierkegaard, ”The Idea of Natural History,” he presented the methodological idea of Kierkegaard (though not by name) as that of allegory: “Whenever second nature’ appears, when the world of convention approaches, it can be deciphered in that its meaning is shown to be precisely its transience.” Paraphrasing Adorno, nature appears at the greatest extreme of second nature.”

Robert Hullot-Kentor (Ibid)

Cleo Wilkenson

Adorno somewhere (in a late lecture) said the idea of philosophy is to say by concept that which is unsayable. He also noted (as Hullot Kentor likes to point out) that philosophy was to put pain into conceptual form. I have tried before to articulate Adorno’s notion of second nature. I quote Camilla Flodin here “As Flodin notes, don’t trust anything that calls itself natural. For it is not. It is second nature. Second nature is death, it is morbidity and decadence. That so many of the solutions (sic) to the crises take authoritarian and Puritanical form should be obvious, and are predictable, but due to the two centuries or so of growing instrumental domination and submission of nature, of man’s capacity to dominate himself, to repress and deform his own emotions and feelings, they are not. Man is more often than not a stranger to himself.”

“Authentic art knows the expression of the expressionless, a crying from which the tears are missing. “

Theodor Adorno (Aesthetic Theory)

That which is expressed by way of the inexpressible. The inexpressible’s lack of expression becomes expression. This is key. There is a kind of collective muteness in actors in film : hidden by the ersatz music.

“Movie music served to underscore the movie’s illusion of immediate, naked life, bringing ‘the picture close to the public, just as the picture brings itself close to it by means of the close-up’.”

Graham McCann (Introduction to Composing for Film)

Eisler & Brecht, Preparatory Committee of the Academy of Arts of the GDR, on 21 March 1950

Graham McCann, in an excellent introduction to the Eisler and Adorno book (Composing for Film) described the Frankfurt School…

“Research in New York The Institute had been established in Frankfurt in 1923, with classical Marxism as the theore tical basis of its programme, but had undergone a radical change in outlook in 1930 when the philosopher Max Horkheimer, an old friend of Adorno’ s, took over as its director. In contrast to the ahistorical, scientistic Marxism associated with the Party, which seemed to discourage prudential forms of political theory, Horkheimer’s Institute proposed a Marxism that was true to Marx’s original, critical project: a theory for the times, a theory that changed with the times. The Institute’s reanimated Marxism was thus a ‘Critical Theory’, radically opposed to dogmatism of any kind, constantly on guard against the twin dangers of fetishizing the general or the particular. The Institute was now committed to a programme of interdisciplinary study, explicating the set of mediations which enable the reproduction and transformation of society, economy, culture and consciousness. { } The Institute was ideally suited to Adomo·s prodigious and heterodox talents. H e became the dominant intellectual influence on most of the Institute’s research projects, both during the American exile and after the return to Frankfurt at the end of the forties (when he became its new director). He remained a resolute defender of the idea of’nicht mitmachen’, not playing along, a refusal to compromise in the name of practical expediency.

His thought resisted the temptation to countenance any premature resolution or reconciliation, seeking to preserve the dialectical unity of part and whole., particular and universal. H e once wrote that, ‘The dialectic advances by ways of extremes, driving thoughts with the utmost consequentiality to the point where they turn back on themselves, instead of qualifying them·. His style was to brush against the grain of conventional thought, employing provocative exaggerations and ironic inversions to bring contradictions into bold relief: ‘the value of a thought’, he remarked, ‘is measured by its distance from the continuity of the familiar’.’Refugees·, wrote Bertolt Brecht, ‘are the keenest dialecticians. They are refugees as a result of changes and their sole object of study is change. They are able to deduce the greatest events from the smallest hints …. When their opponents are winning, they calculate how much their victory has cost them; and they have the sharpest eyes for contradictions.”

Brecht described Hollywood as the ‘center of the international narcotics trade’.

Vaiva Kovieraite

Allow me a further quote here from McCann…“European immigration had reached its peak by 1941. Six hundred and thirteen displaced academics entered the United States between 1933 and 1945 under a rule giving exemption from the quota to any emigres who had taught during the previous two years and had a guaranteed American teaching position. The Emergency Committee In Aid of Displaced Foreign Scholars found places for 459 of them; 167 settled at the ‘University in Exile’, set up by the New School for Social Research in New York. Eisler arrived there early in 1938, teaching a number of courses on music. In terms of numbers, the New School was by far the most important academic centre for emigre scholars in the U.S. It was not, however, the only significant institution associated with emigre intellectuals at that time. In 1934 Columbia University provided a north American home for the Frankfurt Institute of Social Research . In its new location in New York’s Morningside Heights Park, the Institute, under the direction of Horkheimer and characterised by the work of such figures as Adorno (who arrived later than the others, in the February of 1938), Franz Neumann, Leo Lowenthal and Herbert Marcuse, continued its self-consciously interdisciplinary theoretical investigations into the nature and causes of political totalitarianism. Adorno, more so than any of his Institute colleagues, felt illat-ease in his new surroundings. Every intellectual in emigration·, he was later to write, ‘is, without exception, mutilated , and does well to acknowledge it to himself, if he wishes to avoid being cruelly apprised of it behind the tightly-closed”

Graham McCann (Introduction to Composing for Film)

This is an important context for those who denounce the Frankfurt School theorists as dupes of the CIA or somehow inauthentic (see Gabe Rockhill for example). Brecht was critical of Adorno (to a degree)….but Leo Lowenthal, the last original member of the Institute replied …“As for Brecht’s attack on Adorno and his colleagues for their ‘failure’ to unite theory with practice in an appropriately urgent manner, Lowenthal, with bitter sarcasm, replied: True, had Adorno and his friends manned the barricades, they might very well have been immortalized in a revolutionary song by Hanns Eisler. But imagine for a moment Marx dying on the barricades in 1849 or 1871: there would be no Marxism, no advanced psychological models, and certainly no Critical Theory.”

David Moyer

“Just as in Adorno’s aesthetics the art work is socially interpretable not because its represents society but because it acquires its social content through resistance to society and is thus the unconscious writing of history, so Kierkegaardian inwardness, the spiritual ‘interieur’, gains its determinations through negation.”

Robert Hullot Kentor (Ibid)

“There is even reason to believe that the more closely pictures and words are co-ordinated, the more emphatically their intrinsic contradiction and the actual muteness of those who seem to be speaking are felt by the spectators.”

Theordor Adorno (Composing for Film)

Now this is interesting; Adorno is writing at the time about silent film. (or very early talkies). And yet I would argue the residue of this truth, this subliminal muteness, clings to all film and video. That somewhere below the conscious surface of how we watch film and TV is a sense of something unnatural. And this by extension (one could argue) is related to a lot of technology — from smart phones to jet airplane travel to computer processing overall. There clings to the experience something primordially strange, and even uncanny. The experience of high speed travel, for example, suggests something like the feeling of being around someone who is hypnotized. It is in an extreme example, probably how magicians, ,voodoo practitioners, and shamen, created the ‘undead’ and invented narratives of grave robbing and mind control. Much early German expressionist cinema made use of these themes.

Nina Bondeson

The sense of social tension that began in 1847, and on through the fin de siecle, and the early 20th century, and a first World War was then given a kind of final punctuation by the rise of National Socialism. And what is now clear, (and this is what I am trying to get at here) is that National Socialism never died. It was never really defeated. Those emigre Jewish/German artists and thinkers and academics who were given token employment via government programs (scantily funded) or through US government NGOs like the Rockefeller Foundation, et al — they watched as former high ranking Nazis were given much higher profile and certainly better paid positions in business and academia, and at NATO. And the western allies embraced ideas of progress and – the West was firmly entranced with tech and a belief in the infallibility of science. There was nothing that could not be known.

There are two tracks to follow in the construction of an Imperial reality. One is obvious and the other much less obvious but just as significant. One can look at the trajectory of Edward Said’s work and the post colonial (or disimperialist or whatever). See Ben Etherington https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/cambridge-journal-of-postcolonial-literary-inquiry/article/edward-said-and-the-dialectic-of-the-imperialized-intellectual/DDFB23757B6AF00E32DDE09EB0D3819A#fn21

The other is the ‘crossroads’, the shift in inwardness.

“The Skillevei is then submerged in a certain tradition of ‘thinking’: one is always on the way, underway, to the use the timeless image of the road, vej, Weg, camino, chemin, caminho, Tao or bóthar. Kierkegaard’s Skillevei is pivotal for the awakening of inwardness, and at the beginning of Christian Discourses, he writes: “Everywhere in life is the crossroads. Every human being […] stands at the crossroads—that is his perfection and not his merit”. This ‘perfection’ in the Skillevei is the choice that the single individual can make. This is the perfection of that single individual as the ‘antithesis to objectivity’ at ‘that fork in the road’. It is not a ‘merit’, and it is no consolation. “

Bartholomew Ryan (Ibid)

Jane Ianiello

And this is also the road that leads to psychoanalysis. And this is why the Frankfurt scholars were so intent on incorporating Freud into their Marxism. And why so many scientistic Marxists were (and still are) so hostile to Freud. It is curious in its way that Kierkegaard was so reliant on this idea of *skillevei* — the crossroads. For perhaps there is no real choice. This is where Freud enters the discussion. And that’s probably something to cover in part two of this post. Hullot-Kentor paraphrases Adorno on Kierkegaard…“nature appears at the greatest extreme of second nature.” This is Adorno (and Benjamin) on allegory. And this is…to use this quote again ” He clarified this at another point: “One could almost say that the aim of philosophy is to translate pain into the concept.’ This would be the aim of a Hegelian dialectic that bas become the presentation of allegory.”

To donate to this blog (and to the Aesthetic Resistance podcasts) use the paypal button at the top of the page.

https://aestheticresistance.substack.com/

I really like this. I tried to write a response earlier but it was lacking in dexterity. I need to write about it in a more expansive way. But Conrad has always been the biggest inspiration … The first novel of his I read was Victory. At a tender age. I had a crazy great aunt who lived in a deteriorating sprawling house. She was the youngest of 6 or more siblings — all of whom died before I was 5. But she lived until I was in my early 20s and had absorbed all their belongings and never threw anything away. One or two of her sisters were serious readers (she also read voraciously but mainly mass market historical or romance novels — an odd side note not too many people know is that one of Robert Bly’s daughters is Eloisa James — author of Regency and Georgian romance novels and also a tenured “Shakespeare prof” at Fordham). Anyway, I found a very old tattered copy of Victory at her dilapidated house and it was one of the first novels I actively chose to read … previously I was overly influenced in my reading by teachers and family. I thought Victory — the old edition I had found at her house was — looked like a simple and thrilling little read. Little did I know how its contradictions and beauty would fuel my life for decades. I also started reading DH Lawrence and many other authors thanks to the fact that my great aunt kept everything.

great remembrance and I have several much like that. My aunt was a book store manager and owner and when i spent summers at her house, by the beach, I used to pick up books to read. A lot of old Grove Press and the like. It began a lifetimes journey.