Michael Borremans (2014)

“And early in the morning he came again into the temple, and all the people came unto him; and he sat down, and taught them.

And the scribes and Pharisees brought unto him a woman taken in adultery; and when they had set her in the midst,

They say unto him, Master, this woman was taken in adultery, in the very act.

Now Moses in the law commanded us, that such should be stoned: but what sayest thou?

This they said, tempting him, that they might have to accuse him. But Jesus stooped down, and with his finger wrote on the ground,

as though he heard them not.”

John 2-8

“In the antagonistic society, the relationship of the generations is also one of competition, behind which stands naked violence. Today however things are regressing to a condition which does not know the Oedipus complex, but only the slaying of the father. One of the most telling symbolic atrocities of the Nazis was the killing of the extremely old. Such a climate produces a belated and rueful understanding with one’s parents, similar to the one between condemned prisoners, disturbed only by the fear that we, ourselves powerless, may not be able to care for them some day as they cared for us, when they owned something.”

Theodor Adorno (Minima Moralia)

“If I am not mistaken, the heterogenous pieces I have listed resemble Kafka; if I am not mistaken, not all of them resemble each other. This last fact is what is most significant. Kafka’s idiosyncracy is present in each of these writings, to a greater or lesser degree, but if Kafka had not written, we would not perceive it; that is to say, it would not exist. The poem “Fears and Scruples” by Robert Browning prophesies the work of Kafka, but our reading of Kafka noticeably refines and diverts our reading of the poem. Browning did not read it as we read it now. The word “precursor” is indispensable to the vocabulary of criticism, but one must try to purify it from any connotation of polemic or rivalry. The fact is that each writer creates his precursors. His work modifies our conception of the past, as it will modify the future.”

Jorge Luis Borges (Kafka and his Precursors)

““Our salvation is death, but not this one.”

Franz Kafka (Blue Notebooks)

I wanted to mention, before getting into several themes, here, a number of recent bits of writing — posts I guess — short essays— all admirable and all more or less touching on one of the themes here. First is Ed Curtin on the documentary CHAOS

https://edwardcurtin.com/do-you-think-youll-ever-know-now-that-you-have-handed-your-mind-to-the-machine/

and another, by Dennis Riches, which is quite related, I believe; https://dennisriches.substack.com/p/pacifism-realism-opinion-resellers

I was thinking how important writing is, how important books are. And that so much is lost when the young grow up without a love and respect for books. And I was also thinking about the strange cult of kitsch biography. (Adorno used that phrase but I am borrowing it). Kitsch biography is a staple of pop culture, and it is employed mostly in thumb nail sound bites about famous people in order to criticize them or smear them outright. And relatively serious people will site details from the lives of this or that famous artist or thinker or politician as if this serves to bolster their opinion on this person. And this extends to jobs or relationships — or, often, the remarks of children or ex wives or husbands. And often, too, the person pointing out these kitsch biographical details is guilty (by his or her definition) of the same offense. Attacks on Fidel and Mao are common, on Stalin, of course, and any Marxist thinker. But many of these attacks come from the left, although they attack other leftists as much or more than fascists. The Frankfurt School of course are targets. And here is exactly why Freud remains so important and why there is such resistance to his ideas.

Philip Gould, photography. (Albert Leblanc, King of Mobile Homes, Duson LA 1978)

Now, thinking of books and reading Ed Curtin’s piece and that of Dennis Riches also brings to mind Kafka, and then Pynchon and Philip K. Dick. This is the paranoid branch of Kafka’s influence. And there is no contemporary writer that can be cited in this continuum. But then books no longer play the same role they did even forty years ago.

“St. Augustine was a disciple of St. Ambrose, Bishop of Milan, around the year 384; thirteen years later, in Numidia, he wrote his Confessions and was still troubled by that extraordinary sight: a man in a room, with a book, reading without saying the words.”

Jorge Luis Borges (On the Cult of Books)

The subject of the documentary CHAOS, directed by Errol Morris, is Manson and the book by Tom O’Neill. I was in my last year of high school when the so called Manson murders occurred. I knew people who had brushes with Charlie, with other members of ‘the family’. I remember the Sunset Strip and that whole scene. Full disclosure I had dealings with Morris, albeit briefly. He was set to hire me to write a script based on the ‘Lobster Boy’ true crime book. But then, suddenly, without a word of explanation, he ghosted me. And this phenomenon of ghosting is now ubiquitous — it is actually almost a normal reaction for those under thirty. And this is tied to books and the loss of reading, too. I have no real opinion on the Manson story except its not at all hard to believe Charlie was in some way a CIA asset. More interesting to me are the other ideas introduced by Ed and Dennis. And these are the general mental circuits getting crossed, short circuited maybe. The loss of the sacred, of genuine ritual, too, is part of this. Jesus wrote only once, with his finger in the dirt, on the Mt of Olives. And nobody ever read what he wrote.

The short circuiting is the product of post industrial society, the Debord ‘Spectacle’, the attention economy. This theme is echoed in various ways in Latour and and a dozen others. I remember the first Pynchon I read, The Crying of Lot 49. I remember reading it through very quickly. It was a secret message but without the message. A fortune cookie that had nothing written on the paper inside. But more on that below.

People write too much. Or at least don’t rewrite enough or censor themselves enough. Maybe I can be accused of that, too, I don’t know.

I read the Pynchon in my last year of high school (the year of the Manson Murders) and three years after it had been first published. And Dick’s The Crap Artist which was, I think, written six years earlier than the Pynchon but more or less is set in the same northern California. Or A Scanner Darkly(written a decade later and southern California), which is barely science fiction, really, but veers close in places to Pynchon. Everyone is anticipating everyone else. I wrote about the Disney Snow White (1937) on this blog, as it anticipated crane shots and probably Cinemascope (Vista Vision et al). Joan Didion figures here, too, for her central valley Californian-ness. Disney’s Snow White anticipates Sirk, not the lastest remake, nor does it anticipate Barbie. And all of this, including Pynchon, is connected to Kafka but also to Raymond Chandler and the Black Mask writers by way of a new urban anxiety.

Logan Maxwell Hagege

But Pynchon and Dick were mystics, albeit of very different kinds. I’ve never known completely what to do with Pynchon. I’ve read most of the novels, save for Against the Day and Vineland. And I have yet to make it all the way through a DeLillo novel. And these days I find it very hard to read novels. If I do its usually to re-read classics. Dostoyevsky I’ve re-read several times over the last decade. All of the major work, anyway. But the point of The Crying of Lot 49 was that it was, in a sense, the Lacanian novel. It was about the missed appointment, the absence at the center of our lives. Hence, really, it was about psychoanalysis altogether, and it harkened back to fin de siecle with its optical inventions, the new discoveries in a previously unseen world. What we cannot see with the naked eye, and that became over the course of a long 20th century something paranoiac and fascistic. What we couldn’t see became threatening. It went beyond germs and microbes or a means to solve crimes. Clues found in Conan Doyle or Christie, eventually became Manson. That Snow White was made by fascist sympathizer and bigot, Walt Disney, fits in here as if in a puzzle, too. That he, Disney, employed Nazi scientist Werner Von Braun is also just another piece of the puzzle.

But one can never escape Kafka, I don’t think. And if Borges is right, that we create our own precursors, then Auerbach’s thesis in Mimesis, suggests we (our society, our culture) keep reinventing the Old Testament. If Augustine found the man reading in silence, in his monastery cell, uncanny, I suspect this is a profound clue to the subject of books. Oration has tended toward the fascistic. Oration has tended toward the authoritarian. Reading silently has trended the opposite direction.

“The fact is that each writer creates his precursors. His work modifies our conception of the past, as it will modify the future.”

Jorge Luis Borges (Kafka and his Precursors)

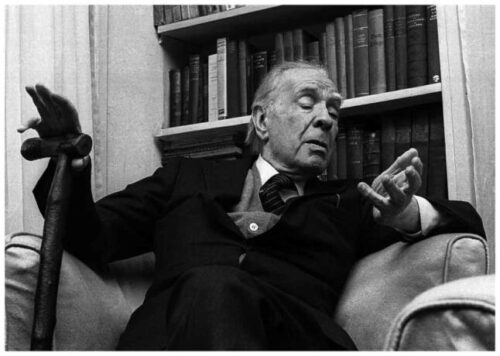

Jorge Luis Borges

The terrible ascension of Zionism is a project that continuously tries to modify the past. It cannot do so in the way desired. The Aesthetic Resistance podcast (#154) discussed the Tantura documentary. The sinister uncanniness of these elder fascists remembering their ethnic cleansing carries with it all colonial history. And this from Borges also. In a conversation with Osvaldo Ferrari…

“That reminds me of Heine, who said that the historian is a retrospective prophet (laughs), someone who prophesies what has already happened.”

Jorge Luis Borges (Conversations, Vol.2)

At the end of that conversation Borges notes the necessity of reading poetry aloud. That it must be heard in order to , finally, understand its truth, or rather, to experience its truth. But then he notes that people have forgotten to hear what they read. Everyone now can read in silence but do not hear the truth, they go directly to the meaning. (Bloom’s insight on Shakespeare’s characters overhearing themselves it linked to this, too.) Theatre and poetry involve speaking aloud. And that is something very different with its own aetiology.

Which is an interesting idea. Certainly the loss of books in culture, of a book culture, has profound implications. And this is really the point of this post. But also that aesthetics is the foundation for social transformation. I really do believe this but its not a novel idea.

“The two men both conceived of a collective soul, which becomes especially relevant in the context of war neurosis. Simmel used the term Volkseele, or “soul of the people.” While the soul of the diseased individual expresses war neurosis through the body, the diseased soul of the people expresses its war neurosis through its economy. A few years later, in his fictionalized psychoanalytic case study Two Girlfriends Commit Murder, Döblin employed the terms Seelenmasse, or “soul mass,” and Gesamtorganismus, or “collective organism,” to express the idea that individuals could not be described without consideration of their rooms, their houses, and their streets.”

Veronika Fuechtner (Berlin Psychoanalytic)

Mircea Suciu

The two men are Alfred Döblin and George Simmel. Later, of course, Fassbinder made his most brilliant film in the adaptation of Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz.

“Structural violence and militarism affected the very circles whose ideology stood in opposition to war. With the figure of Link, Döblin criticized what he perceived to be “the dictatorial wing of the workers,”which by 1930 he deemed militaristic, authoritarian, and ultimately too dogmatic: “Nowhere can the terrible effect and rigid domination of the centralistic tendency be seen as well as here, where the masses think like socialists, but they are led against the capitalist class in a single-minded fashion, which forces them into a warring spirit and an organizational mold, and they can’t help but become armies.”

Veronika Fuechtner (Ibid)

This was a fear that ran through the socialist minded psychoanalysts in Berlin, in particular. Wilhelm Reich certainly saw this danger. I think there are interesting connections, as when Borges noted he read Amerika for the first time while Kafka was still alive. I was in the same city and in the same clubs and concerts and parties (!) as Manson and his family. Chandler wrote The Big Sleep in 1939, the start of WW2. Kafka died in 1924. Döblin had Berlin Alexanderplatz published in 1929. World War 1 ended in 1918. Precursors and anticipation.

Dennis Riches observed (and I am sure this will be a discussion in the next podcast) that the ‘Goa Inquisition’, which was an extension of the Portuguese Inquisition in all of Portuguese India, and which was carried out in the 15th century, did not just end. The Church never stopped the Inquisition or the office of the Inquisition, not until around 1820. Dennis observed anti-communism came along after that to replace the Inquisition. And this is a brilliant remark, really. And it relates to the Döblin and Simmel thoughts on the spread of a martial mindset under the guise of being anti-war. Much as the crew of The Pequod, whose job was the slaughter of whales, were all Quakers.

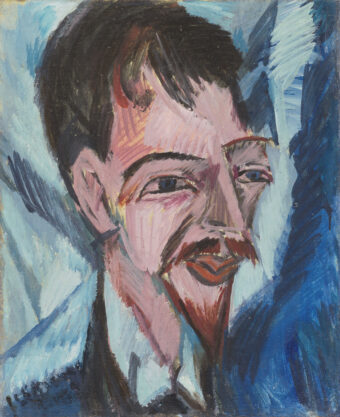

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (portrait of Alfred Döblin, 1912)

“The imagery that Döblin deployed in Two Girlfriends Commit Murder reemerged in Simmel’s later work on war neurosis. During his exile in Hollywood, and influenced by World War II, Simmel returned to the topic of war neurosis and elaborated on his theory by drawing on the concept of the ego that Freud had been developing since the early 1920s. Simmel described the state of mind preceding neurosis as the “military ego.” The soldier’s superego was weakened and had been externalized: the superiors came to function as the superego. At the moment the superiors mistreated the soldier, he had to come to terms with betrayal, which was experienced as a betrayal within himself. The soldier fought not only for his nation and for his physical survival but also for the survival of his soul. The ego became a battlefield.”

Veronika Fuechtner (Ibid)

There is a telling passage in Berlin Alexanderplatz where Biberkopf, the troubled violent recidivist is analysed by doctors at psychiatric hospital.

“The narrator includes this diagnosis in his description of Biberkopf’s soul as something that is regressing and wandering, as something that reaches back into the animal stage and joins the “gray mice” that live in the walls—the border between the inside and the outside, and metaphorically the border between the conscious and the unconscious.”

Veronika Fuechtner (Ibid, quoting Döblin’s novel)

Ernst Bloch on kitsch:

“Here even what is insipid readily comes together. It writes for unalert people in the style they wish for themselves. The inside of the readers is itself squashed here, their outside they perceive is not the one in which they really are. A writer who did not deal in cut-and-dried feelings would not find any place here, in a stratum which lives by lying to itself and being lied to, which not only wants, but is itself largely kitsch.”

Ernst Bloch (The Heritage of Our Times)

We live in a time of kitsch politics, certainly. And one of the many offenses one can direct at kitsch is that it interrupts this sense of modifying both the past and future. The issue of precursor.

Bruce Gilden, photography.

“ In Brecht’s work, however – and he is a matador of change, of the rewriting of something soi-disant concluded – the case is different. Structures like ‘The Threepenny Opera’, ‘Mahagonny’, even ‘Man is Man’ were really written too early, i.e. not yet properly adequate for the material and its problems. Thus when Brecht, as conscientious and cohesive author, patrols the front of his creations, certain burlesque, sometimes anarchistic, sometimes again all too collectivist features (particularly in ‘Man is Man’) fall out of line. Yet more important is another unfinished aspect, one to be valued extremely positively, and this does not concern only the author. Brecht wants to change the audience itself through his products, so the changed audience (and Brecht now belongs to it himself) also has a retroactive effect on the products.”

Ernst Bloch (The Heritage of Our Times)

But without books, without reading, there can be no anticipation. In a sense this is what we have in the contemporary world. A world without precursors. A world that cannot anticipate. Borges obsessive reading has been tracked by Argentine librarians who researched all the books he took out of libraries in that country for all of his life.

“The craft of reading is a mysterious one. No one knows (certainly not readers themselves) how the words captured by the eye on the page are transmuted into experience, reflection, memory and sometimes into new creations. By what means does Saxo Grammaticus’s dry Danish chronicle become the tragedy of Hamlet, or how does a snippet in the yellow French press become the story of Madame Bovary? Borges’s readings are a literary genre in themselves.”

Alberto Manguel (Borges reads Kafka)

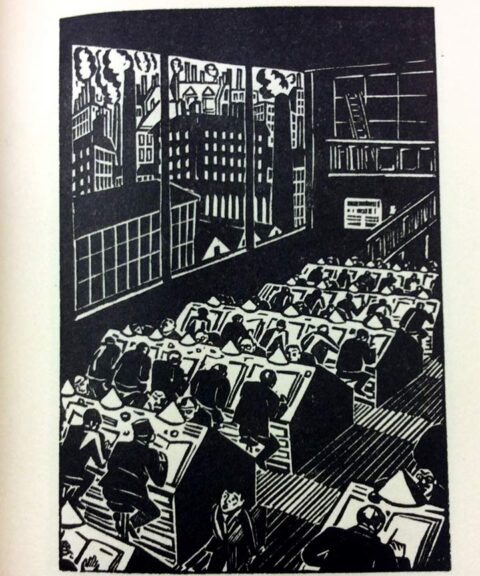

Frans Masereel, woodcut illustration for Landschaften und Stimmungen: 60 Holzschnitte , 1929

“To summarize,we would say that Kafka as well as influencing Borges also makes it possible to think that the real subject of Borges’s work (like Kafka’s) is something like literary influence itself.”

Rex Butler (Re-Reading Kafka and His Precursors)

But there is something else lurking around the edges of the above quote, and that is the Inquisition, the ongoing genocides and fascist sensibilities. Snow White of 1937 was partly birthed by Hitler, at least its mise-en-scene, and Disney studios resembled NASA, if not the V2 rocket research lab at Peenemünde. Pope John Paul, the most fascist modern Pope, and his sucessor came from the modern day Vatican institution of the Inquisition, though re-branded as the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. Ratzinger, often called God’s Rottweiler, was the retroactive precursor for Torquemada. But Butler’s quote touches on something else, and that is the question of influence itself. { and speaking of curiosities of coincidence https://thedebrief.org/did-wernher-von-braun-actually-predict-elon-musk-would-rule-mars-over-70-years-ago/#:~:text=%E2%80%9CThe%20government%20of%20Mars%20consisted,%2C’%E2%80%9D%20von%20Braun%20wrote.}

Now this may seem if not abstruse, at least esoteric, and I’m sure it is. And yet there is some truth buried in it all, in the deeper symbolism and allegorical significance of texts. And cultural influences. Once the noir films of the 30s and especially the 40s, often made by emigre Jewish/German directors and writers, but also scripted by former newspaper reporters or writers of pulp detective fiction, reflected a deep societal anxiety and distrust of authority, but also expressed the textures and emotional tensions of daily life, and which drew from German expressionism but also from several different branches of Romanticism, and were precursors for the melodramas of Sirk and one could claim even screwball comedies. In fact Sirk allowed a new perspective on directors like Fritz Lang and Robert Siodmak. Vaudeville fed into a stream of comedies that included the Marx Brothers, and later Burns and Allen, Milton Berle and others. From another direction Chaplin and Keaton. And Keaton was a precursor for Beckett, but so was the Old Testament. The sunlit noir of the early 50s was an answer to McCarthyism (Aldrich’s Kiss Me Deadly, Lang’s Of Human Desire or Phil Karlsen’s The Brothers Rico…even Joseph H. Lewis Gun Crazy). To McCarthyism, a new incarnation of the Inquisition. In theatre there was a triumvirate of Beckett, Genet, and Ionesco, and then Pinter. All anti-establishment and (in Ionesco’s case directly anti fascist), but they helped create Bernhard and Handke and Muller and Franz Xavier Kroetz. And Botho Strauss. By the 60s there was less to anticipate. In the 70s even less. In film Fassbinder and Godard, the entire French New Wave and the British New Wave. In Italy after the war came a wave of leftist filmmakers, staunchly anti fascist; Pasolini Visconti, De Sica and Antonioni and Rossellini and Bertolucci. But the point is not that there are not great films made today, because there are. Fewer it is true. But that the precondtions for cultural movements seem dissipated. And there is some significant theatre today, though not much. And in literature the post Pynchon American novel seems dead. There was Denis Johnson perhaps, and now Kem Nunn (except he seems busy doing TV). Highsmith produced Didion. Didion re-created Highsmith, and everyone read Highsmith differently I think. But by the Reagan years the vapidity of the Democratic Party was seeing off the last East Coast WASP writers, Updike and Cheever, or urban Jewish voices like Saul Bellow. But finally all of them felt minor (Updike was a better art critic).

The last generation of great English language poets ended with the death of Robert Bly recently. Before him Robert Lowell, and Kinnell and James Wright and Roethke — maybe one or two others. Berryman was a more interesting critic, and Auden has his place. But after them, what?

Luc Tuymans

And then the internet. The internet seems to have been the death blow to cultural precursors. To influence as an idea or reality. When I say internet I mean more than just the technology. I mean the economic changes, I mean robotics and computerized trade and transport. But even more than that I mean this triggering of what very quickly became a cascading wave of algorithmic changes in even perception. Not only the loss of reading and books but clearly the loss of thought.

Auerbach’s Mimesis, has, as time has passed, become ever more important. It captured something gone. Nobody could write that book today. The last few who could approach it, Franco Moretti say, are very old. And Auerbach’s ideas on the King James Bible lead us to Kafka, and Freud, and then Beckett and Pinter, and Pasolini. But there it stops. The fall of the Soviet Union was the first fatal blow. It created anti-anticipation, and anti-influence. And it reinvigorated the Inquisition. And then the internet, born of a military program, came to function as a great engine of mystification. It needn’t be so, I believe the internet still could be a force for liberation. But that would require an awakening.

Half a century ago Ernst Bloch addressed a group of University students on the state of education and the hostility to Marx that was taking over institutional thinking.

“The first basic doctrine is that of surplus values, squeezed out of the worker. This is the instrumentality whereby every society was based on profit and indeed, mutatis mutandis, every class society has maintained itself, together with the division of labor, ideology, and all that goes with it. Ricardo has demonstrated that the value of commodities is determined by the work time required for their production. But if the worker in selling his commodity of labor receives its equivalent value in the form of a wage, the genesis of surplus value for the capitalist remains a riddle, one which from the viewpoint of the bourgeoisie has no possible solution. Marx, however, demonstrated that the worker is not paid the full value of his labor, but only the amount he needs in order to reproduce his power to work. That is, the worker is selling not his work but his power to work. In the unpaid portion of the work, Marx discovered the source of surplus value, and ultimately the basic motivation for the existence and maintenance of the whole commodity-producing society. Marx’s work surveyed for the first time the transformation of men and things by capitalist society into commodities, and the ghostlike reduction of all use values by their transformation into exchange values, and thus explained them as phenomena that could be eliminated. Since then, we have known what commodities, the circulation of commodities, and the entire process of the reification of life connected with it really are: a relationship between men concealed under a crust of things, and of a transitory nature. This insight into the nature of commodities revealed the causation of the increasing pallidity, misery, and vapidity of human life.”

Ernst Bloch (On Karl Marx)

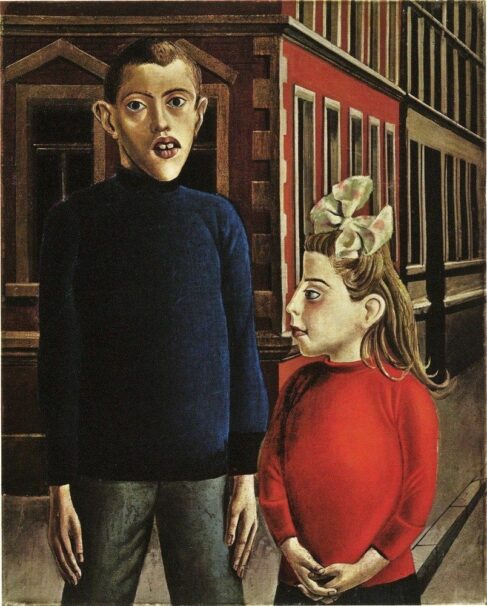

Otto Dix (1921)

Fifty some years on and the pallidity, misery and vapidity of life is even more acute. I think this brief summary is as good as any explaining the basic and probably most important aspect of Marx. It should be a PSA for the entire society. And this is why the contemporary insistence on conflating communism and fascism is so problematic.

One retort that is heard often is that ‘oh, we have always had inequality, and always had class division, etc’. Or whatever other crisis surfaces the retort is, ‘oh but this is nothing new’. And usually this is true, at least to a degree. But while this or that crisis may be familiar in terms of its structure or appearance, or even how it began, or the mechanisms that brought it into existence, contemporary society is NOT the same. The inequality baked into capitalism now occurs in a dramatically denuded material landscape, a dramatically polluted and ugly material landscape, but it also involves a markedly deteriorated subjectivity overall.

The Goa Inquisition banned Hindus, burned books in Sanskrit and Hindi, and Marathi, and he colonial administration under the direction of the Jesuits and Church Provincial Council of Goa (1567) banned Hindu priests from conducting weddings, or from holding any religious services. Violations of this strict code of Christian practice was punishable by beatings, whippings, and even burning at the stake. Every single colonial project, from the Caribbean, to India to South America to the Philippines and Micronesia — and all of Africa, followed pretty much the same principles. Today Israel is the last great colonial project and it is an Inquisition and bans Muslims from anything resembling equality. The Inquisition (fascists) will insist on their new definitions of freedom and liberty. RFK Jr has called Palestinians the most pampered people on earth.

“We have created our myth. Myth is a faith, a passion. It is not necessary that it be a reality. It is a reality to the extent that it is a goad, a hope, faith, courage. Our myth is the Nation, our myth is the greatness of the Nation. And to this myth, to this greatness – which we want to translate into a fulfilled reality – we subordinate everything else. For the Nation is above all Spirit and not just territory”

Benito Mussolini (Discorso di Napoli Oct 24th, 1922)

Carl Grossberg (self portrait, 1928)

Harold Bloom, of course, wrote an entire book on ‘influence’. He was examining English language poetry, but much as I find Bloom irritating, he isn’t stupid. And to understand influence, in relation to allegory, and to history (memory, our own repressed material) is only through narrative. Through prose and poetics. As if, perhaps, influence itself only exists in a dialectical relation to text. Bloom in the introduction writes of Shakespeare’s Sonnet #87…

“Whether Shakespeare ruefully is lamenting, with a certain urbane reserve, the loss of the Earl of Southampton as lover, or as patron, or as friend, is not (fortunately) a matter upon which certitude is possible. Palpably and profoundly an erotic poem, Sonnet 87 (not by design) also can be read as an allegory of any writer’s (or person’s) relation to tradition, particularly as embodied in a figure taken as one’s own forerunner.”

Harold Bloom (The Anxiety of Influence)

This is, essentially, how rhetoric, how symbol and metaphor and reality intersect. For it is always both/and. Not either/or. Our relationship to a lost love or friend IS the same stuff as our relation to tradition or history. The Inquisition, which was re-branded as anti-communism (The Red Scare) was also an embed in all colonial dynamics. All colonialism is an inquisition. And influence is inextricably tied to resentment. ( I will write an entire post, soon, on resentment). The artistic impulse comes from the inspiration of earlier artists. And while this is true in music and painting as well, these mediums still require narratives we construct. Bloom also said, rightly (very close in how I have written of re-narrating) that with Shakespeare (who he said ‘invented humanity’) there was a development of ‘overhearing ourselves’ (he used Hamlet and Falstaff in particular). The point here is that inspiration becomes resentment. In one way, the anxiety of influence is an Oedipal narrative.

Now ‘overhearing ourselves’ is how traditions are built. Reading in silence is also a tension in American culture going back to the Quakers and their sitting in silence, which in turn is akin to most Christian devotions, where the mind is to be cleansed of clutter. Bloom astutely notes that Shakespeare’s characters never fully listen to each other. This is also the invention of, at least, modern humanity. It doesn’t matter if Freud’s anthropological narratives ‘really’ happened, the same as it doesn’t really matter if any origin story ‘really’ happened, as described, because the idea of a beginning and end is finally moot. There was no beginning and there can be no end. And humanity is burdened with that fact.

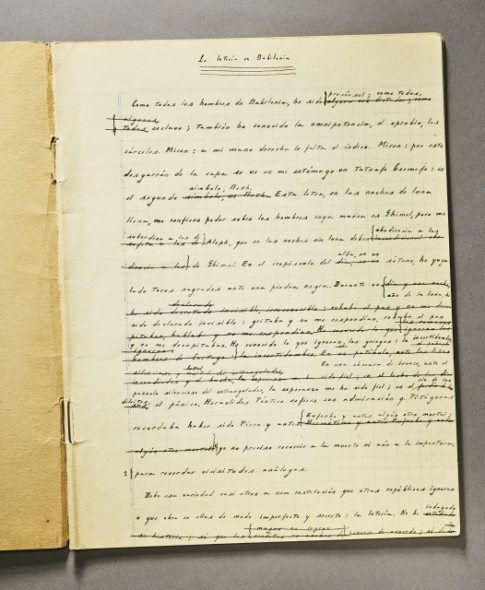

Original hand written copy of Borges’ The Lottery in Babylon.

“Erich Auerbach once told {Geoffrey} Hartman a story of a violinist forced to leave Germany and wishing to take up his profession in America: “Alas, his violin no longer emitted the same ‘tone’ in the new country.”

Allister Heyes (The Anatomy of Bloom)

In Hollywood today (and even in British TV) the number of writers employed continues to shrink. And this is especially true of drama series. Executives simply do not trust their own taste and hire the same writers over and over and over and over, even if their previous work was less than successful. The repetitiveness of stuff is stunning, actually. Someone like Guy Ritchie makes the exact same show again and again. And this is normalized. The self plagerism, the surfeit of imagination, it becomes routine. Repetition is anticipated. This is the only anticipation left. And this is partly what *camp* is, where there is an over appreciation of the terrible and cliched. Of course this is also what advertising does, and tries to underscore the familiarity. Television shows have always been basically junk with occasional quality sneaking in. But today there is a new repetition, a new ‘kind’ of repetition. And it is performed with a knowing wink indicating we all are aware its junk. Irony. Ironic repetition, then.

Allow me to segue here to a remarkable essay by Guy Davenport on Kafka’s story The Hunter Gracchus. It is among the most haunting of Kafka’s works, and among the most beautiful. And to understand more completely our intimate relationship with history, how it is that history is like a fugitive romance or desire, I think Davenport is worth reading on that Kafka story but also reading Davenport, and how Davenport read him.

Davenport notes that in Kafka’s diary, April 1917, while down at the small Harbour in Prague, he saw a strange very worn and nearly dilapidated boat newly anchored. He asked after it and was told that it put in only every two or three years. And that it belonged to the Hunter Gracchus. Kafka’s description is very like Melville’s for The Pequod. In both there is a sense of timelessness, of ancient seafaring and endless seas.

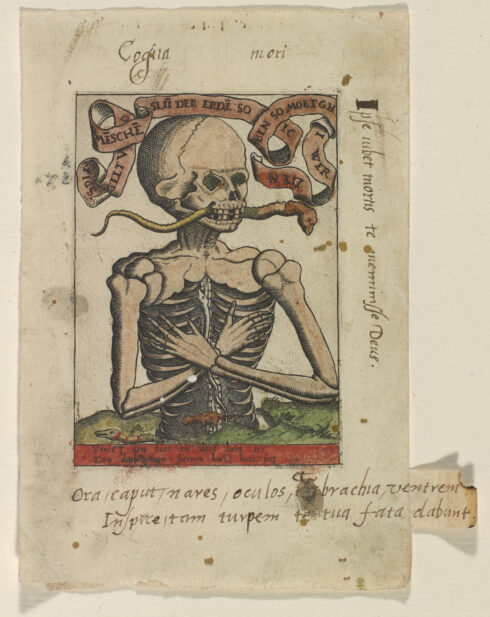

Master Alexander van Brugsal (Flemish 1520)

“From Noah’s ark to Jonah’s storm-tossed boat out of Joppa to the Roman ships in which Saint Paul sailed perilously, the ship in history has always been a sign of fate itself.”

Guy Davenport (On the Hunter Gracchus)

Kafka wrote an unfinished first version of this story (referred to now as the Hunter Gracchus fragment) and between that draft and the slightly longer final draft Kafka was reading Wilkie Collins’ Armadale. In it a dying murderer comes to a spa in the Black Forest in hopes of writing a confession that will somehow avert the passing on of his sins to his son. The story is about the futility of such hopes. This reading provided Kafka with a staging, as Davenport describes it, but it also reminded Kafka, I think, why one enjoys wandering down to harbors at all.

“The first paragraph of “The Hunter Gracchus” displays the quiet, melancholy stillness of Italian piazza that Nietzsche admired, leading Giorgio de Chirico to translate Nietzsche’s feeling for Italian light, architecture, and street life into those paintings that art history calls metaphysical. The enigmatic tone of de Chirico comes equally from Arnold Bécklin (whose painting Isle of the Dead is a scene further down the lake from Riva). Bocklin’s romanticization of mystery, of dark funereal beauty, is in the idiom of the Décadence, “the moment of Nietzsche.” Kafka, like de Chirico, was aware of and influenced by this new melancholy that informed European art and writing from Scandinavia to Rome, from London to Prague. Kafka’s distinction is that he stripped it of those elements that would quickly soften into kitsch.”

Guy Davenport (Ibid)

Kafka could not remember if he had ever met Einstein, although it is likely they did meet during this period, at one or another gathering or party. It is important to understand just what an outlier Kafka was, on so many levels. I immediately thought of Hermann Broch when I began Davenport’s essay and sure enough he crops up halfway through.

“Hermann Broch placed Kafka’s relation to myth accurately: beyond it as an exhausted resource. Broch was one of the earliest sensibilities to see James Joyce’s greatness and uniqueness. His art, however, was an end and a culmination. Broch’s own The Death of Virgil (1945) may be the final elegy closing the long duration of a European literature from Homer to Joyce. In Kafka he saw a new beginning..:”

Guy Davenport (Ibid)

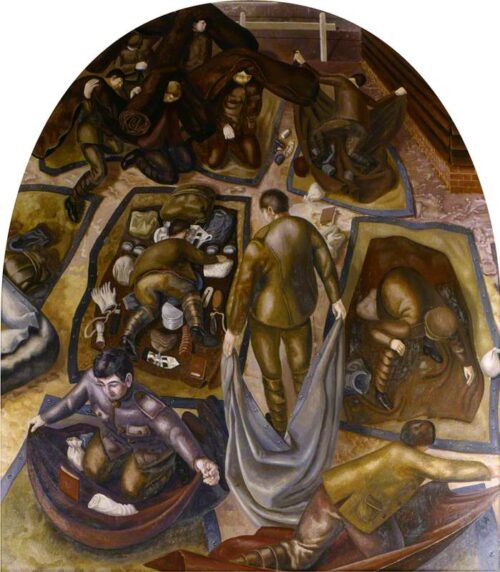

Stanley Spencer (Sandham Chapel)

Kafka’s sister (the one who had rented his apartment in the old quarter, the medieval quarter, of Prague, and where he lived while writing Gracchus) died in the camps. There is a quality in Kafka that suggests antiquity, sometimes, and at others suggests something far older. It is the repressed part, kept beneath the obsidian like reflective hard clarity of his prose. Kafka prophet of the camps.

Broch wrote (quoted by Davenport) : “The striking relationship between the arts on the basis of their common abstractism [Broch wrote], their common style of old age, this hallmark of our epoch is the cause of the inner relationship between artists like Picasso, Stravinsky and Joyce. This relationship is not only striking in itself but also by reason of the parallelism through which the style of old age was imposed on these men, even in their rather early years. “

This is a brilliant insight. And this is a part of the uncanniness of Kafka. Broch continues…

“In Joyce one may still detect neo-romantic trends, a concern with the complications of the human soul, which derives directly from nineteenth-century literature, from Stendhal, and even from Ibsen. Nothing of this kind can be said about Kafka. Here the

personal problem no longer exists, and what seems still personal is, at the very moment it is uttered, dissolved in a super-personal atmosphere. The prophecy of myth is suddenly at hand. “

Hermann Broch (Introduction to Rachel Bespaloff’s De /’Iliade, 1943)

In Kafka the personal problem dissolves. Everything personal becomes collective, and the everything personal becomes prophecy.

“Prophecy. All of Kafka is about history that had not yet happened. His sister Ottla would die in the camps, along with all of his kin. The German word for insect ( Ungeziefer, “vermin”) that Kafka used for Gregor Samsa is the same word the Nazis used for Jews, and insect extermination was one of their obscene euphemisms, as George Steiner has pointed out. “

Guy Davenport (Ibid)

Hermann Broch

The rise of National Socialism remains the indelible event for the 20th century. But American imperialism is a part of this, as is British colonialism. And there was (often noted) an administrative and efficient ethos to Nazi policy — the Frankfurt School thinkers observed this repeatedly. Listen to Eichmann in Jerusalem. Davenport describes Kafka’s German….“a pure German, the austere German in which the Austro-Hungarian empire conducted its administrative affairs, an efficient, spartan idiom admitting of neither ornament nor poetic tones. Its grace was that of abrupt information and naked utility.” The rise of instrumental logic, of an administered world, began at the end of the 19th century, really. As the Industrial Revolution was being, finally fully digested.

“The first truly “total war” of the democratic age and the society of the masses was the Great War, in which 13 million men perished. It was the founding act of the twentieth century. In August 1914, it was acclaimed in most European capitals as an opportunity to affirm the values of the nationalist ethos (virility, strength, courage, heroism, and union *sacree*) in the purificatory fire of warfare. But its violence was to submerge the whole world. The intoxication of patriotism gave way before the discovery of the modern horrors of anonymous mass slaughter, industrialized massacre, bombed towns, and ravaged countrysides. { } …soldiers now became a proletariat, workers in the service of a war machine. Stripped of the aura of the ancient warrior, soldiers were subjected to a military discipline in every way comparable to that of industrial production. The “worker masses” of a Ford-type factory were now matched by the “soldier masses” of modern armies. { } The army as a whole was converted into a rationalized, mechanical business with a hierarchy and a bureaucracy, and separate, coordinated sectors In which tasks were distributed on a strictly functional basis.”

Enzo Traverso (Origins of Nazi Violence)

Davenport notes “Walter Benjamin, Kafka’s first interpreter, said that a strong prehistoric wind blows across Kafka from the past. “ This is the feeling I was trying to get at earlier. Kafka is an emissary from the deep past.

“Mein Kahn ist ohne Steuer, er fabrt mit dem Wind, der in den untersten Regionen des Todes blist.” (My boat is rudderless, it is driven by the wind that blows in the deepest regions of death.) This is the voice of the twentieth century, from the ovens of

Buchenwald, from the bombarded trenches of the Marne, from Hiroshima. “

Guy Davenport (Ibid)

This is the final line of The Hunter Gracchus. Kafka dreamed Pynchon and Dick. One was Joycean and one was writing sacred books, books of religious intoxication. Both retroactively were trying to decode how fascism had not gone away. It was hiding.

Anton Räderscheidt (1921)

“Time in Kafka is dream time, Zenonian and interminable. The bridegroom will never get to his wedding in the country, the charges against Joseph K. will never be known, the death ship of the Hunter Gracchus will never find its bearings.”

Guy Davenport (Ibid)

The Hunter Gracchus suggests we are already dead. Traverso, in a chapter titled “A Laboratory of Fascism” :

“The racist dehumanization of the enemy and the growing indifference with regard to human life also found expression in a brutalization of political life, which now adopted the language of warfare and methods of confrontation inherited from the trenches.”

Enzo Traverso (Ibid)

Traverso is writing of National Socialism but he could be writing about Israel and Zionism.

“Edward Said and Michael Adas are right to stress that the colonial culture is not just a form of propaganda and that the imperialist ideology should be taken seriously: nineteenth- century Europe was truly convinced that it was accomplishing a civilizing mission in Asia and Africa. At the time of decolonization, the imperialist culture was stigmatized, violently rejected, and subsequently forgotten; it never became the subject of in-depth analysis, and today remains still largely repressed.”

Enzo Traverso (Ibid)

The return of the repressed.

One hears the echos of fascism (the anticipations, the precursors) in much of the Climate Discourse, and in American exceptionalism.

“The notion of “living space” was not a Nazi invention. It was simply the German version of a commonplace of European culture at the time of imperialism, in the same way as Malthu- sianism was in Great Britain. The idea of a “living space” inspired a policy of conquest and was invoked to justify the goals of pan-Germanism. Meanwhile, Malthusian theories were regularly used to legitimate famine in India-which some observers of the time accepted as “a salutary cure for over-population.” The concept of “living space,” as much. as the “population principle,” postulated a hierarchy in the right to existence, which became the prerogative of the nations, or even “races” that were dominant. The expression “Lebensraum” was coined in 1901, under Kaiser Wilhelm, by the German geographer Friedrich Ratzel (1844-1904) and had become part of the vocabulary of German nationalism well before the advent of Nazism. It resulted from the fusionn of social Darwinism and imperialist geopolitics, and stemmed from a vision of the extra-European world as a space to be colonized by biologically superior groups. “

Enzo Traverso (Ibid)

To donate to this blog use the paypal button at the top of the page. Donations also go to keeping the Aesthetic Resistance podcasts afloat.

Speak Your Mind