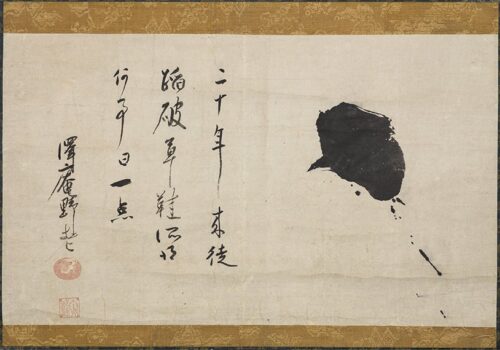

Takuan Sōhō (1573-1645)

“Advertising power houses use psychoanalytic techniques under the rubric of “theater of the mind,” and only the marginalized think to argue with success.”

Jonathan Beller (Cinematic Mode of Production)

“In the case of the Sagrada Família, being a man with such a powerful imagination, Gaudí was constantly making changes to it as the building progressed. They’ve started work on it again now, adding new things as it nears completion, and it will probably end up looking completely different. The man from whose imagination it grew has passed on, so I think it’d be best not to work on it any more but to leave it unfinished.”

Ando Tadao (Art It)

“What is represented in ideology is therefore not the system of the real relations which govern the existence of individuals, but the imaginary relation of those individuals to the real relations in which they live.”

Louis Althussar ( Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays )

“The spectacle presents itself simultaneously as all of society, as part of society, and as instrument of unification. As a part of society it is specifically the sector which concentrates all gazing and all consciousness.”

Guy Debord (Society of the Spectacle)

9 Therewith bless we God, even the Father; and therewith curse we men, which are made after the similitude of God.

10 Out of the same mouth proceedeth blessing and cursing. My brethren, these things ought not so to be.

James 3:9-10

I was watching the remake of the 1972 thriller Day of the Jackal (based on the Fredric Forsythe novel) and it was remarkably bad for several reasons, but also remarkably revealing. First off this was an 8 part series (in other words they had 8 hours, roughly, to tell their story). The first thing that jumps out at you is the casting. Eddie Redmayne is the eponymous assassin and he, and his cheekbones, are fine. The 72 film had Edward Fox in the role and mostly they are both essentially walking stoically through this archetype (or cliche), though with 8 hours Redmayne was tasked with utterly pointless scenes of home life. Now right there, you see, is the first problem. But lets not call it a problem. Humanizing cold sociopathic killers is something entertainment has done for a while (and political consultants do every day). Forsythe avoided this in the book. In fact the final line of the 72 film is, ‘then who was this guy’?, over the unmarked paupers grave of the killer. Here of course we need season two. But more to the point is the invention of a counter figure. The hunter, inexplicably Lashana Lynch was cast. A british blacktress, who may or may not be good, but is very very very bad in this. First off she doesnt appear to be in good enough shape to pass the most basic fitness course. Second she is just irritating. And I’m not alone in this assessment. We do not believe she knows guns or shooting. So why was she cast? I can only assume a kind of wokeness was at work. But bouncing back and forth between Redmayne and Lynch was disconcerting. Anyway, the more salient point was that one feels relief when Lynch is shot by the assassin. And it sets up season two. But this is an interesting narrative point; as I say immoral killers have gotten away with it before in Hollywood, but this was something else. This was something like what Adorno notes in an early chapter (sic) of Aesthetic Theory. And the fact that audiences for such series are fully aware and anticipate a second season makes the killing of the *good* CIA/MI6 agent a half unintended comment on politics in general. Lynch’s death is directed at Keir Starmer.

“Art responds to the loss of its self-evidence not simply by concrete transformations of its procedures and comportments but by trying to pull itself free from its own concept as from a shackle: the fact that it is art. This is most strikingly confirmed by what were once the lower arts and entertainment, which are today ad ministered , integrated , and qualitatively reshaped by the culture industry . For this lower sphere never obeyed the concept of pure art, which itself developed late . This sphere, a testimony of culture’s failure that is constantly intruded upon this culture , made it will itself to failure -just what all humor , blessedly concordant in both its traditional and contemporary forms, accomplishes. Those who have been duped by the culture industry and are eager for its commodities were never familiar with art: They are therefore able to perceive art’s inadequacy to the present life process of society – though not society’s own untruth – more unobstructedly than do those who still remember what an artwork once was.”

Theodor Adorno (Aesthetic Theory)

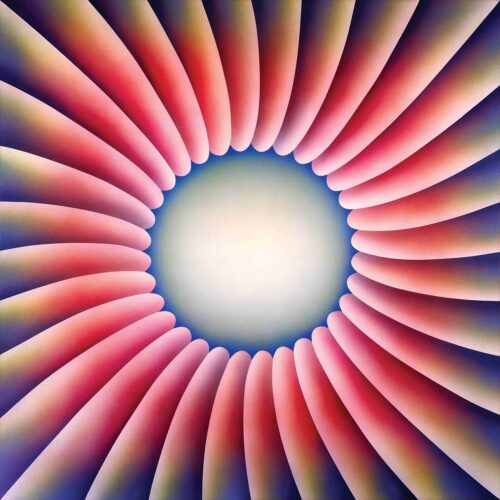

Jim Dine

Now hold that thought. Earlier in that paragraph Adorno writes of Oscar Wilde’s interiors (Dorian Gray) resembling the auction houses and smart antique shops Wilde so hated. The unconscious reproduction of bourgeois thought forms. The clumsy plot considerations of Jackal are an expression of art as emotional protest, in the same way a vote for Trump was a *protest*. But these are disfigured and highly mediated protests, coming out of an acute unbearable sense of ambivalence. Voting Trump was not a *real* protest but a form of electoral spitting on the whole circus. Day of the Jackal is spitting on the genre , the one sort of inaugurated by Forsythe. So there are several tiers here. The lone assassin has one trajectory that probably began with Charles Bronson in The Mechanic (1972) — script by Lewis John Carlino and directed by the rather neglected Michael Winner. In the case of this film the appeal was much like that of Tracker (2024, which Ive spoken of before) where this was a fantasy job for most American men of this time. And of now. The killing didn’t matter, there was freedom. Economic freedom and you could play with guns and technology and for many working class boys in the U.S. the idea of culture and self betterment was very appealing if you could do it looking like Charles Bronson. Winner created a sort of kitsch intellectual figure in the meticulous virtuoso of assassination Arthur Bishop (Bronson). But no wife, no kids, no obligations or mortgages or rent or 9 to 5 job. The so called Long Retreat of Empire was in full swing by 1972. This was also the last gasp, or the start of the last gasp of counter cultural culture(sic). And most of that was in southern California, in fact. But it was already a parody of something earlier, of a legimately driven avant garde. (Bengston, Noland, Dennis Hopper photographs, Diebenkorn et al).

The second tier operative here is psychoanalytic. Arthur Bishop does not exist without Jan Michael Vincent, his protege (and there is a painful irony in the tragic Vincent being cast as fledgling psychopath in training). The effectiveness of the story is its Oedipal underpinnings. Hollywood’s sense of lost relevance is increasingly expressed in a kind of narrative and visual impotence. And this is meant only half metaphorically. But what I am suggesting is a kind of unconscious form that accommodates and creates an existing social tension. But this leads to several related questions. Bishop sips fine wine and listens to classical music, both signifiers for what Americans view as intellecutalism — and hence suspicious. But Arthur Bishop is a stone cold killer, and his virtuosity and emotionless professionalism is obviously his appeal. The idea of the professional looms very large in the American imagination. Bishop completes his jobs. He deserves his wine and the *art* on his walls (a Bosch no less). It cannot be lost on anyone that The Mechanic was released the same year as the original Day of the Jackal. One other note is both Bishop and the original Jackal had no backstory. They were existential ciphers for authenticity. The 2024 Jackal however spends a lot of time giving us Redmayne’s backstory. And of course it includes the military and Imperialist wars in the middle east.

Judy Chicago

“Fantastic art in romanticism, as well as its traces in mannerism and the baroque, presents something nonexistent as existing . The fictions are modifications of empirical reality . The effect they produce is the presentation of the non-empirical as if it were empirical . This effect is facilitated because the fictions originate in the empirical. New art is so burdened by the weight of the empirical that its pleasure in fiction lapses. Even less does it want to reproduce the facade. By avoiding contamination from what simply is, art expresses it all the more inexorably.”

Theodor Adorno (Ibid)

Now one might want to add science fiction into this discussion but perhaps more importantly, or significantly, to add Children’s Literature that is embraced by adults (Tolkien, J.K. Rowling, and stuff like Suzanne Collins). There always exists a quality of the cautionary about children’s literature. This is not found in the Brothers Grimm, or fairy tales in general. The lesson or even warning is more materialistic with fairy tales, in a sense, and hence also more metaphysical. Stuff like Lord of the Rings tends toward this denial of what exists while reproducing it — but through a lens of banality. It must poach from what exists but either through cheap analogies or just an imaginative exhaustion, these counter worlds tend toward a childishness not meant to be identified with by children readers or viewers.

“Today every work is virtually what Joyce declared Finnegans Wake to be before he published the whole: work in progress. But a work that in its own terms, in its own texture and complexion, is only possible as emergent and developing, cannot without lying at the same time lay claim to being complete and “finished.” Art is unable to extricate itself from this aporia by an act of will. “

Theodor Adorno (Ibid)

Almost every great art work of the 20th century, and of philosophy to a degree, is unfinished or a work in progress. And this raises the idea of second seasons and as Kermode put it, the sense of an ending. The emergent became an artificial moment of suspense that is left in the air for viewers to wait for until Season Two. This is why the *official* canon of TV franchises have all had such unsatisfactory finales. (Sopranos, Mad Men, Breaking Bad, Dexter, Hannibal, et al). There is virtually no autonomy in Hollywood product. Not anymore. As a side bar, after watching Netflix’ Chernobyl, it was good to see Max Parry was already on the case https://www.globalresearch.ca/hollywood-reboots-russophobia-new-cold-war/5687362

and Dennis Riches

https://www.globalresearch.ca/hbos-chernobyl-cautionary-tale-about-splitting-atoms-another-chapter-anti-russia-propaganda/5681524

The point being that anti-communism is always always always a guaranteed prestige award getter.

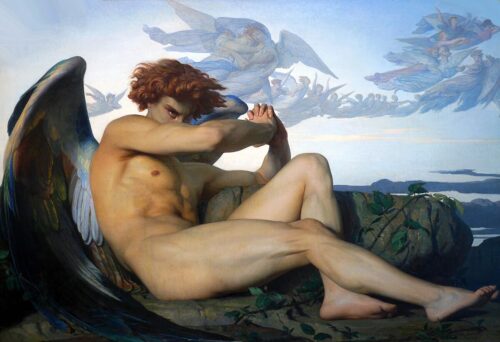

Alexandre Cabanel (Fallen Angel, 1847)

Adorno notes the problem of weighing art down with ‘intentions’. A form of ‘having an agenda’. But that is only one version of insisting on intention. And with a second season being the goal of most series work coming out of Hollywood, intentions haunt nearly everything produced.

“What is today called a “message” is no more to be squeezed out of Shakespeare’s great dramas than out of Beckett’s works. But the increasing opacity is itself a function of transformed content. As the negation of the absolute idea, content can no longer be identified with reason as it is postulated by idealism; content has become the critique of the omnipotence of reason, and it can therefore no longer be reasonable according to the norms set by discursive thought. The darkness of the absurd is the old darkness of the new. This darkness must be interpreted, not replaced by the clarity of meaning. The category of the new produced a conflict. Not unlike the seventeenth-century querelle des anciens et des modernes, this is a conflict between the new and duration. Artworks were always meant to endure; it is related to their concept, that of objectivation . Through duration art protests against death; the paradoxically transient eternity of artworks is the allegory of an eternity bare of semblance. Art is the semblance of what is beyond death’ s reach. To say that no art endures is as abstract a dictum as that of the transience of all things earthly; it would gain content only metaphysically, in relation to the idea of resurrection.”

Theodor Adorno (Ibid)

Films today seem to age more quickly than they did fifty or sixty years ago. And series franchises seem oddly incoherent when viewed after a mere twenty years. Part of this is the lack of interior coherence. Characters and actors both feel peripheral to the work. Cinema is not literature and while an Antonioni or even Godard — in his early days — or Fassbinder, created nearly impossible to believe depth and complexity in their stories, or a Sirk or Siodmak, or Fritz Lang even, all from different strategies, it is hard not to sit back and ponder where that all went. Another example of today’s egregiously stupid prestige vehicles is The Agency, written by prestigy british playwright Jezz Butterworth and starring Michael Fassbender, late of the now defunct Drama Centre London (which was, though not entirely, a victim of the Covid lockdowns and now defunct). The show is another MI6 spy/espionage drama, co starring Jeffrey Wright and Richard Gere (no, really). And, (in a weird way paralleling Jackal) a British born former model Jodie Turner Smith. Smith is black, tall, and speaks with a trained posh accent. She plays a Somali sociologist (or something, anthropologist maybe) who has met Fassbender’s spy while working in Africa. Never mind, if Lynch did not convey belief in her firearms training, then Smith does not convey belief in anything. And there is a curious coldness between her and Fassbender. It is a profoundly reactionary script. Profoundly. It is also racist and paternalistic toward the global south. I can only assume Butterworth phoned this one in. He clearly knows how to write better than he shows in this mess. Gere is no better than he has ever been. Worse maybe. Gere cannot convey intelligence. Just cannot do it.

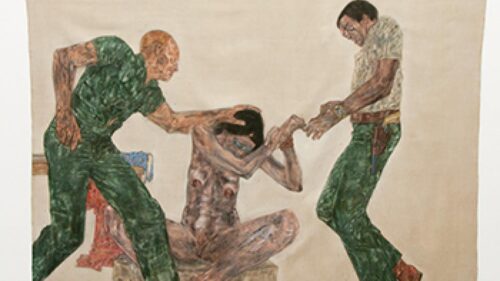

Leon Golub

The deeper problem with The Agency is the seemingly intractable condescension the English display toward their former colonial subjects. Butterworth is English and among his most applauded plays is The Ferryman, set in Ireland during ‘the troubles’. An Englishman writing an *Irish* play did cause controversy. And offense. Butterworth however has clearly not suffered career wise. I compared him (and I believe misspoke on the podcast referring to him as her) to Caryl Churchill and its not a terrible comparison, but one could add Alan Bennett or Michael Frayn. I mean nearly all are Cambridge or Oxford educated. And these plays (unlike Pinter, who Butterworh makes a lot of noise admiring) are in the end valentines to the status quo. We love the status quo because we can criticize it in our plays, but still live on and be well paid. Pinter was not educated at Cambridge.

But this brings me back to plots and Jackal again. If English theatre forms itself unconsciously around stories trending toward affirmative views of English class hierarchy, even as they often stridently do not, then Hollywood (even if its made in England) tends toward affirmation of its moral superiority. English writers see a society flawed but worth saving and American writers see their own virtue and THAT is worth saving, and to save it means, ok, rescuing society. Even working class origins (Howard Brenton or David Hare for example) still end up at Cambridge or Oxford. The last working class non Cambridge or Oxford playwright of note was Edward Bond (who died only months ago). And it is hard not to compare the generation of Bond and Hare and Brenton and even back to John Osborne with the current group of playwrights gracing the Royal Court etc. But what has changed? I think in general the voice of the working class is simply silenced today. Those who aspire and maybe get into Oxford or Brown or Carnegie Mellon or Yale, their working class background is now scrubbed. They lose it. The generation of Hare and Bond this was, largely, not true. But today it is true.

British actors in general are superior. Technically they are and the writers are technically better. But Jodie Turner Smith is the colonial occupiers wet dream, an Orientalist figure out of a harem. In this case given an abusive Somalian husband (the savages!).

“In this regard, the category of tragedy should be considered. It seems to be the aesthetic imprint of evil and death and as enduring as they are. Nevertheless it is no longer possible. All that by which aesthetic pedants once zealously distinguished the tragic from the mournful-the affirmation of death, the idea that the infinite glimmers through the demise of the finite, the meaning of suffering-all this now returns to pass judgment on tragedy. Wholly negative artworks now parody the tragic. Rather than being tragic, all art is mournful, especially those works that appear cheerful and harmonious. “

Theodor Adorno (Ibid)

Farshid Bazmandegan

Now The Agency is not even half over so I will withhold further comment. The germane take-away though is the validation of the secret services, of espionage in general and of Imperial ambitions. They go unquestioned. The rise of film and TV has altered the relations of other mediums with the collective subjectivity of their audiences.

“Technique, the extended arm of the subject, also always leads away from that subject. The shadow of art’s autarchic radicalism is its harmlessness: Absolute colour compositions verge on wallpaper patterns. Now that American hotels are decorated with abstract paintings ‘a la maniere de’ … and aesthetic radicalism has shown itself to be socially affordable, radicalism itself must pay the price that it is no longer radical. Among the dangers faced by new art, the worst is the absence of danger.”

Theodor Adorno (Ibid)

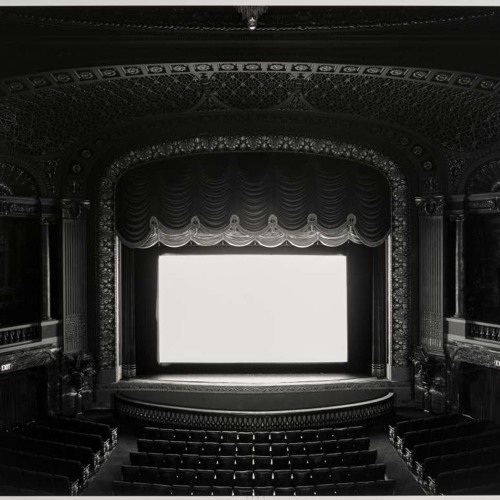

Film and TV are, firstly, always existing in a strange dynamic with the hegemonic power of Hollywood. And film and film aesthetics, or interpretation, have been shaped, to a considerable degree, by studio authority and box office. No other art form in history has been so mediated by finance. And today, as technology allows micro budget films to be made, the power of Hollywood shifts to distribution. Visibility. Popularity. But why should that matter so much? Great poets are never read by many people, great novels even and certainly fine arts overall are seldom objects of mass adoration or rejection. Film IS about success on a certain level. Box office returns are headlines often before critical reviews. Unlike the novel (though not entirely) films are always about success. The very idea of art-film is not exactly antiquated but rather feels to threaten the cognoscenti with a realization that artfilms were never exactly ‘artfilms’ to begin with. Certainly the question of autonomy is genuine, and its loss, almost completely, is part of the crisis of filmmaking today, but beyond that the entire evolution of ‘feature films’, the not quite two hour duration, the role of early movie theatres to view them, and the rise of the *movie star* and of later of ‘hit’ TV series and its increasingly incorporation into the DNA of public life exists in an uncomfortable tension with nearly all other issues of western imperialism. I have said all stories are about homesickness and exile. All film narratives are too, but they are additionally about success. Even Soviet films were not immune to this.

Economic considerations and strategies shaped how film was marketed and sold. All of this is a well known history. The point here is that film and TV, and both are tightly conjoined now, have shaped western (and maybe global) ideas of self and other. People increasingly, since the internet, are unable to think outside the film form — our psyches to a degree are interpreted by ourrselves as we interpret film. The world is a movie, but more and more a private movie we watch in our own subjective empty theatre.

The Mechanic (Dr. Michael Winner, 1972)

I wrote above that film today (from Hollywood, which perhaps means all film) expresses something of both societal impotence, but also the impotence felt in the audience. If one compares a tracking shot by Max Ophuls, or Nick Ray, and then one by Speilberg or the Cohn Brothers, or Chloe Zhao say, I think one sees (or feels) the loss of something. And this is becoming a refrain with me, I realize. Loss. And it is pointless to try to describe ‘what’ is lost, because its not that kind of loss. It is a sense of film form cannibalising itself, where the camera in Lola Montes, for example, becomes the absence of camera movement in any number of films made today. The camera tracked itself out of existence in a sense. Tracking shots still exist but we can’t see them. Film as it mediates daily life throughout the 20th century, was also swallowing its own tail — Hitler and the Nazis fixated on movies and dreamed dreams that anticipated Cinemascope. (Fassbinder, in A Year of 13 Moons, creates a Rogers and Hammerstein-esque dance sequence, part Jerry Lewis and part Nazi fantasy. Fassbinder knew Hitler and Göring wanted Guys & Dolls on a vast Albert Speer stage from Riga to Warsaw — this was a big part of Generalplan Ost). The Nazi dream of an eastern Europe cleansed of Slavs and Jews and Gypsies was a cinematic image, and if this Germanification of Eastern Europe, this dream of a Greater German Reich sounds suspiciously like the Eretz Yisrael Hashlema or Eretz Israel, that’s because it is eerily identical.

“As we shall see, the organizational role of visuality, and the transformation of the mode of production arise directly out of industrial production. The ramification and organization of the visible by visual technologies is part of the emergent calculus of the visible. Materially speaking, industrialization enters the visual as follows: Early cinematic montage extended the logic of the assembly-line (the sequencing of discreet, programmatic machine-orchestrated human operations) to the sensorium and brought the industrial revolution to the eye. Cinema welds human sensual activity, what Marx called “sensual labor,” in the context of commodity production, to celluloid. { } Cinema was to a large extent the hyper-development of commodity fetishism, that is, of the peeled-away, semi-autonomous, psychically charged image from the materiality of the commodity. The fetish character of the commodity drew its energy from the enthalpy of repression—the famous non-appearing of the larger totality of social relations. With important modifications, the situation of workers on a factory assembly line foreshadows the situation of spectators in the cinema. “

Jonathan Beller (Cinematic Mode of Production)

Beller is one of the best thinkers of the last several decades, but even with Beller, his actual taste in film is reasonably bad. And this is a topic I know will come up again and again on the podcasts. But this failure in discernment leads to the subtle reductionism in the above paragraph.

Hieronymus Bosch (Death and the Miser, detail. 1492)

Commodity fetishism, by the fin de siecle, was itself being shaped by cinema. Film helped shape the fetish character of the commodity. The ‘hyper development of commodity fetishism’ was part of a ‘movie’ by early the 1900s. Certainly it was by sound film. And it is no accident that mid century fascism, both Italian and German, was immersed in cinematic representations of their mythology. The advent of sound is hugely significant, actually, for the spoken text triggered something authoritarian in the medium — and this is probably worth an entire posting later on.

“Cinema took the formal properties of the assembly line and introjected them as consciousness. This introjection inaugurated huge shifts in language function. Additionally, the shift in industrial relations that is cinema indicates a general shift in the organization of political economy, and this change does not occur because of a single technology.”

Jonathan Beller (Ibid)

I often think film theory tends to devote too much attention to visuality — almost sort of fetishizing it. Obviously cinema is a visual medium but the viewing of film does not isolate the eye from the entirety of the experience.

“…this world-historical role for cinema, and the dependence upon the organization of the visible world (as visuality) demands a total reconceptualization of the imaginary. The imaginary, both as the faculty of imagination and in Althusser’s sense of it as ideology—the constitutive mediation between the subject and the real as “the imaginary relation to the real” —must be grasped not as a transhistorical category but as a work in progress, provided, of course, that one sees the development of capitalism as progress.”

Jonathan Beller (Ibid)

The work in progress. Capitalism is not prone to completion, to the finishing of things. Or rather it doesn’t care if its finished. Capitalism is about beginnings. Breaking ground. Nobody is around at the end of things. Capitalist time is not exactly Christian time. It is time only in so far as it is, or while it is, productive. It is Puritan time, Calvinist time, and is this productive ideological core that grew such deep roots in the United States.

LInconnue de la Seine (death mask of unknown girl found drowned in Seine, 1880s)

“In my own view, the ongoing crisis that drives capital to continual, infinite expansion—specifically, the falling rate of profit—also drives the century-long fusing of culture and industry inaugurated by and as cinema. The expansion of capital, once markedly geographical and now increasingly cultural (corporeal, psychological, visceral), deepens, to borrow Stephen Heath’s words, the relation of “the technical and the social as cinema.”

Jonathan Beller (Ibid)

Whatever the dynamics and forces of cinema in its early days, the focus here is this ‘increasingly cultural’ expansion. And since the internet this expansion is total. Nothing is not a movie on some level at this point. Beller says “cinema is, in the twentieth century, the emerging paradigm for the total reorganization of society and (therefore) of the subject.”

Culturally speaking, as one example, there has arisen a narrative shorthand, where certain objects carry enormous character defining qualities. A bag carried with a baguette sticking out the top signifies groceries and shopping. And of course often even more than that. But facial expressions, too, are instinctively adapted by actors from an established menu of choices. The recent Aussie series Territory has a poster (or one sheet or whatever they call it now) with actress Anna Torv in the center. Her expression is one found in all such homesteader narratives. (Territory is the Australian copy of Yellowstone essentially) It is also nearly always a ‘period face’. These stories are historical reconstruction or settler or pilgrim narratives and the protagonist is usually always white and determined and virtuous. And like Yellowstone, even when set in the present, it is set in the past. The point though is one could quite literally find a dozen examples of that exact expression (see Helen Mirren in 1923 for example). This is the nostalgia of the colonizer. I have not watched Territory but I suspect I could pretty well anticipate the entirety of the show based on that one expression. This expression is accompanied by the steely eyed and jutting jawed posture of the patriarch (even when a women, who is almost never a matriarch).

Renato Bertelli (Profilo Coninuo, 1933. Head of Mussolini)

It is important to understand not just the importance of aesthetics for resistance to the growing Imperialist/fascist West, but to remember the role of the modernist impulse and sensibility in much global resistance.

“One of the most significant aspects of this culture-wide phenomenon was the fascination that American fi ction held for Italian writers. Starting with Cesare Pavese, many of the period’s major literary figures wrote about, discussed, and, above all, translated volume after volume of American fiction. Elio Vittorini translated novels by William Saroyan and Erskine Caldwell. In 1940, he edited for the publisher Bompiani a crucial anthology of American fiction entitled Americana. Alberto Moravia translated works by Theodore Dreiser, Ring Lardner, and James M. Cain. Eugionio Montale worked on Pound, Melville, Steinbeck, and Fitzgerald. Pavese himself introduced to Italy Melville’s Moby-Dick, as well as works by Sinclair Lewis, William Faulkner, John Dos Passos, and Sherwood Anderson. As has been widely discussed, this interest in American realist fi ction, its characters and style, would become a central influence on the subsequent development of neorealism. The most celebrated example was, of course, Luchino Visconti’s Ossessione (1943), which was loosely based on James M. Cain’s The Postman Always Rings Twice. The significance of this phenomenon during the fascist period, however, is that it simultaneously added to a popular mythology of America while also providing discursive terrain on which cultural resistance to fascism could be located. Giaime Pintor later reflected that “this America doesn’t need Columbus. It is discovered inside ourselves, a land for which one holds the same hope and the same faith of the first emigrants, of anyone who, at the cost of errors and fatigue, has decided to defend human dignity.”

Steven Ricci (Cinema and Fascism; Italian Film 1922-1943)

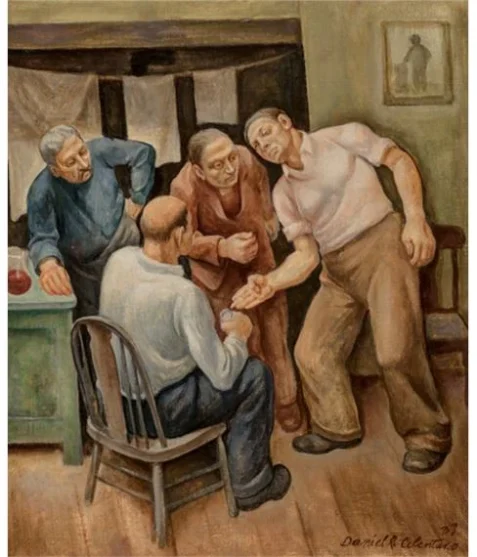

Daniel Celetano (1940)

The fascist government in Italy controlled dubbing for Italian film and this was meant to enforce a strict control of morality, and ideology — and had the additional effect of repeating the voice of fascism. Everything carried a certain tone both familiar and patriarchal. The dubbed voices, even with female voices, were ‘male’. The translations took on the quality of masculinity. Close-ups were authoritarian and the dubbing was fascist. Everything sounded as if spoken to a crowd. It was also in the case of Italy, the voice of the Vatican. The sound of Catholicism. Of Catholic morality.

“…“cinema” refers not only to what one sees on the screen or even to the institutions and apparatuses that generate film but to that totality of relations that generates the myriad appearances of the world on the six billion screens of “consciousness.” “Cinema” means the production of instrumental images through the organization of animated materials.”

Jonathan Beller (Ibid)

The contemporary post internet cinema has replaced fascist dubbing with reserve depository of virtual symbols ( among them facial expressions like the steadfast and principled colonizer) and codes that convey meaning largely in place of (though still somewhat in conjunction with) the text/narrative. And this is a fluid ongoing process of meaning management. And it is operative in nearly unconscious ways (plural). For example, Days of Heaven came out in 78. Terrence Malick’s prestige art-Western became a sort of stand-in for a certain type of Indie film aesthetics. The film also took 2 years to edit because there was so much film shot but also because none of it fit together, quite. The film took an inordinate time to shoot as well with many crew members walking out. Now, like several later Malick projects this can be seen as unfinished. Malick studied philosophy at Cambridge (sigh) and did a translation of Heidegger’s The Essence of Reasons, and before that graduated with honors from Harvard.

There are interesting aspects to his later work, especially (perhaps) The Tree of Life. Malicks’s own younger brother (a guitar student of Segovia) committed suicide, after intentionally breaking both hands — presumably due to the pressures of his musical studies. Malick though, is not as interesting a filmmaker as he should be. I will be argued with about such a statement, and I appreciate that, because Malick is not at all uninteresting. But none of his films are more than ideas for films. I am pretty sure the pitches were better than the end product. (I have not seen A Hidden Life). His cosmic documentary, A Voyage of Time is, frankly, a snooze fest — and I say that because it seems to have utterly forgotten whatever the impulse was to make it in the first place. (there is a comparison buried in there with Carlos Reygadas’ Silent Light, 2007) But Malick himself is also a touchstone for multiple codes. Days of Heaven is the Ur- Indie coffee table book beautiful — film project. Once you empty enough from the artwork, you immunize yourself from criticism. And that includes dialogue. There is, at a certain point, safety in silence. Not all emptiness is meaningful. Malick studied with James Cavell, which might explain some of his aesthetic shortcomings. Art is not philosophy. I’m not sure philosophers make great artists. They can be theorists to a degree, Bresson wrote great aphoristic notes on cinema, and Richter has written on Adorno and fine art, but actual academic philosophy, like Malick did, seems to actually get in the way of the unconscious and sensual mimetic process. There is also the issue of text and dialogue. Pinter’s exquisite screenplays for Losey are operative on another and I would argue deeper level than a film like Tree of Life. Pinter is accessing the unconscious from another place, and this takes us back to Auerbach’s Mimesis yet again. Pinter establishes something Biblical in The Go Between, for example, that Malick cannot do. Fassbinder’s Berlin Alexanderplatz is Old Testament, and its possible The Go Between is closer to the Gospels.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, photography.

“The new is the longing for the new, not the new itself: That is what everything new suffers from. What takes itself to be utopia remains the negation of what exists and is obedient to it. At the center of contemporary antinomies is that art must be and wants to be utopia, and the more utopia is blocked by the real functional order, the more this is true; yet at the same time art may not be utopia in order not to betray it by providing semblance and consolation. If the utopia of art were fulfilled, it would be art’s temporal end.”

Theodor Adorno (Ibid)

Michael Cimino is the flip side of Malick. The Deer Hunter (78) and Heaven’s Gate (1980) deserve long second looks now. The latter of course probably single handedly sunk United Artists. In retrospect Cimino was both neurotic and obsessive (and was notorious for leaving many projects unfinished) but unable to translate that obsession into a ‘sublime’ he dreamed about, but did not really feel. He came up as a screenwriter with Magnum Force (the Eastwood sequel of sorts to Dirty Harry) in 1973 and there is a touch of anti-intellectualism about Cimino that suggests something deeply reactionary as well. There is a worthy (and natural) comparison to be made between Days of Heaven and Heaven’s Gate. But Cimino was also instinctively fascistic and pitched projects based on Ayn Rand, and Solzhenitsyn. If Malick was obsessive and narcissistic then Cimino was just deeply staggeringly neurotic and then, secondarily, narcissistic. Malick is the western Tarkovski in a sense. Cimino is closer to D.W. Griffith.

Shirley Goldfarb

“Brecht’s efforts to destroy subjective nuances and halftones with a blunt objectivity, and to do this conceptually as well, are artistic means; in the best of his work they become a principle of stylization, not a ‘fabula docet’. It is hard to determine just what the author of Galileo or The Good Woman of Setzuan himself meant, let alone broach the question of the objectivity of these works, which does not coincide with the subjective intention. The allergy to nuanced expression, Brecht’s preference for a linguistic quality that may have been the result of his misunderstanding of positivist protocol sentences, is itself a form of expression that is eloquent only as determinate negation of that expression. Just as art cannot be, and never was, a language of pure feeling, nor a language of the affirmation of the soul, neither is it for art to pursue the results of ordinary knowledge, as for instance in the form of social documentaries that are to function as down payments on empirical research yet to be done. The space between discursive barbarism and poetic euphemism that remains to artworks is scarcely larger than the point of indifference into which Beckett burrowed.”

Theodor Adorno (Ibid)

The above paragraph is something many on the left simply refuse to understand or accept. Brecht’s early In the Jungle of Cities, or even Baal, are still extended poems and might remain his best work. There is great value in Mahagony but even as I *appreciate* it, I reluctantly know there is a problem. The left seems to always want moral instruction (and political).

“There is an obvious qualitative leap between the hand that draws an animal on the wall of a cave and the camera that makes it possible for the same image to appear simultaneously at innumerable places. But the objectivation of the cave drawing vis-Ii-vis what is unmediatedly seen already contains the potential of the technical procedure that effects the separation of what is seen from the subjective act of seeing. Each work, insofar as it is intended for many, is already its own reproduction.”

Theodor Adorno (Ibid)

This is an important insight, I think. For it cuts across much of the mystification of technology and its impact on aesthetics. Like an over fixated attention on the visual, there is an over fixation on the technologies involved in art making today. And with the audience and its relation to that technology.

Birth of a Nation (dr. D.W. Griffith, 1915)

Art finally cannot be disconnected from dreaming, nor from the unconscious. One of the best noirs ever made is The Big Sleep, and the storyline is incoherent. It literally makes no sense if you graph it out. And people have. But it hardly matters. The chemistry between Bogart and Bacall is a story unto itself, and Hawks shot the film as if it were a documentary….thereby making it the most poetic of noirs. For it is exactly within that dialectic that the very NON theoretical Howard Hawks intuited the point of cinema. And the text, incoherent though it is, contains enough from the fragments of Chandler, William Faulkner, and Leigh Brackett to infuse the film with the quality of something like a Jacobin tragedy. I often wonder with directors like Malick, if they have any idea at all what to do with actors. One gets the sense they wish they could do without them. Bresson wished that, too, and Au Hazard Balthazar is cited as the film where Bresson found his perfect lead actor….a donkey.

But Bresson knew WHY he used non actors in his films. I am not sure Malick knows why he DOES use them. And this opens a very large topic which we left back at the start of this post: film acting. But that will have to be more exhaustively discussed next blog post.

“Utilizing vision and later sound, industrial capital develops a new, visceral, and complex machinery capable of interfacing with bodies and establishing an altogether (counter)revolutionary cybernesis. This increasing incorporation of bodies by capital co-opts the ever-increasing abilities of the masses to organize themselves. As a deterritorialized factory running on a new order of socially productive labor—attention—cinema as a sociological complex inaugurates a new order of production along with new terms of social organization, and thus of domination. “Cinema” is a new social logic, the film theater the tip of the iceberg, the “head of the pin.” The mystery that is the image announces a new symptom for analysis by contemporary political economy. Production enters the visual and the virtual enters reality. Labor as dissymmetrical exchange with capital is transacted across the image.”

Jonathan Beller (Ibid)

One of the reasons Pasolini’s Gospel According to St Mathew (1964) is so brilliant (I think it may be the single greatest film ever made) is that Pasolini sees Jesus as a labor organizer, both material and metaphysical.

In a Year of 13 Moons (Dr. Rainer Werner Fassbinder) 1978

To donate to this blog (and the Aesthetic Resistance podcasts) use the paypal button at the top of the page.

You should have said “spoiler alert ” I didn’t know Lynch was in for a shooting since I’m only at episode 5. (I’m under the impression that there are a total of 10 episodes.)

It did strike me that Lynch was totally miscast and would ironically have been more convincing as the Jackal’s wife while Úrsula Corberó, who played his wife, would have been more convincing in the Lynch role. (Corberó had already played a lithe acrobatic agent in Money Heist.)

Redmayne looks good but is totally off from the moment he starts to speak. The notion of professional killers having a family life doesn’t ring true at all and the bit where he finds out that his family have found out about him led me to half expect a Kaiser Schoze family elimination scene which would have rung more true for the actions of a professional killer but then again such a killer would never have started a family anyway.

Now excuse me whilst I veer into “tin foil hat” territory but I can’t help noticing that whilst this Jackal series unfolds as a sympathetic assassin opposed to an unlikeable establishment figure, we are presented with a tremendously high profile similar juxtaposition with Luigi Mangione and Brian Thompson.