Sax Berlin

“In the beginning may have been the Uroboros: male and female, father and mother, mother and child, ego-id and outside world in one. But the Uroboros has busted a long time ago; the distinctions and divisions are our reality—real with all its symbols. In the light of its own possibilities, it may well be called a cave, and our life in it dream or death.”

Herbert Marcuse (Love Mystified; A Critique of Norman O. Brown, Commentary Magazine)

“Actaeon; alien horns added to his forehead; the dogs that sated themselves in the blood of their own master; all for the sin of seeing. Cur aliquid vidi? Why did I have to see something?”

Norman O. Brown (Apocalypse; Ovid, Metamorphoses, III, 1)

“Throw out our older, more reptilian part, and our inner sister/brother gets very angry. It can’t be ignored. And on the way to the wedding, in which of course the bride will wear a white dress and the groom will be dressed in black and white, you’ll likely meet this older sibling again and you’ll have to have your courage with you. The chthonic part has kept us going for millions of years; it has always been connected with our continued existence, that snake thing in there. It strikes and survives. Without that one, we’d have never gotten where we are. We’d have died out.”

Robert Bly (More than True)

I increasingly find myself returning to several themes or topics. One is early childhood development, and what increasingly feels like a wrong turn(s) in contemporary thinking on this, and second, the nature of psychoanalysis and the cultural flight from Freud (and his original circle) in contemporary culture.

The third theme can best be described as the origin of life idea and the implications of this question. And I want to begin with a reconsideration of Norman O. Brown. There has been a certain smugness about Brown, in current Academia. A condescension. And this runs alongside the anti- Freudianism in North America in general. I think, like the attitudes toward Marx, one sees much more interest and study in the global south for both. Writing of Brown’s first book (first major book)…

“The Psychoanalytical Meaning of History, is itself, up to a point, evocative of Freud: the book will apply a theory based upon individual psychic histories to the history of mankind itself.In its general outlines, that theory is familiar to most of us. Infantile desire is inevitably repressed by reality,leading to neurosis’, repression is inevitable because desire is founded on dual instincts, life against death, and only the former instinct can be (partially) sublimated. As Brown notes, Freud himself realized, however, that individual neurosis “exhibits a regressive pattern… [in] the slow return of the repressed”.”

C.F. Dyck (Norman O. Brown’s Body: Archetypal Metamorphosis,Mosaic: An Interdisciplinary Critical Journal, Vol. 22, Summer 1989)

I am coming to think one of the core problems with contemporary thinking is to not look at the whole mystery of life, or existence. Academia by its nature tends to compartmentalize. Also, any study of human psychology will not want to visit ancient history or myth. And this means not thinking about art or culture historically, or at all. Capitalism wants to erase history.

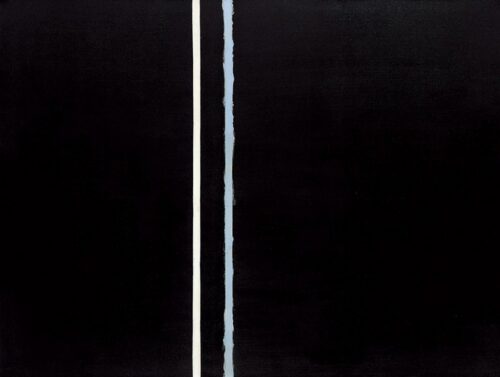

Barnett Newman (1949)

Now, the most enlightening critique of Brown is a rather negative one, from John Simon. Simon once gave me a horrible review , but I shall overlook that (I believe it was for Teenage Wedding, when we did it in NY. That’s ok, that play got me a PEN-West award later.) Anyway, Simon’s problems with the book are exactly why the book remains so important. Or rather, books. For he is reviewing Love’s Body even more than Life Against Death.

“…the chapter headings. Before I venture where he has feared to tread, I had better evoke the form, which, as in all mystico-symbolic works (and, according to McLuhan, in television) is the message. In her otherwise extremely cogent review of Love’s Body, Brigid Brophy commits the one error of deriving its form fromWittgenstein’s Tractatus. Even the most cursory glance into Wittgenstein, as well as the mere consideration of Brown’s anti rationalism, would suffice to eliminate anything as rigorously methodical from the parentage of Love’s Body. The aphoristic-didactic style with its meandering, sometimes footstep-retracing, sometimes subterraneous and unfollowable, progression, and with its cryptically Orphic, Messianic, indeed millenarian utterances, is clearly related to the mystical and prophetic works, the sacred books of all time and all place, whose high-water mark in the modern era was Thus Spake Zarathustra, and whose last ripple Miss Susan Sontag’s “Notes on Camp”.”

John Simon (Brown’s Body, The Hudson Review, Vol 19)

Now the problem, rather conspicuously, is Simon’s demand for a certain rational summation of themes. He cites Brown being contradictory but seems unable to imagine that such *contradictions* can be viewed from alternative perspectives. Simon in his very tone, in the DNA of his sentences, is validating everything Brown has written.

“…religion is precisely what Brown is peddling, despite his assertion what we need is poetry, which, he says, is voluntatary mystical participation. But Brown’s is a religion because it preaches, anathematizes, and commands. Even while he is a mentality, his book is a monument to it: banish reason, possession, the self, or perish!; even though he is for affirmation he is haranguing away against the rational, the individual, the precious, the precisely defined. Poetry is non-prescriptive; Brown, like other religionists, prescribes.”

John Simon (Ibid)

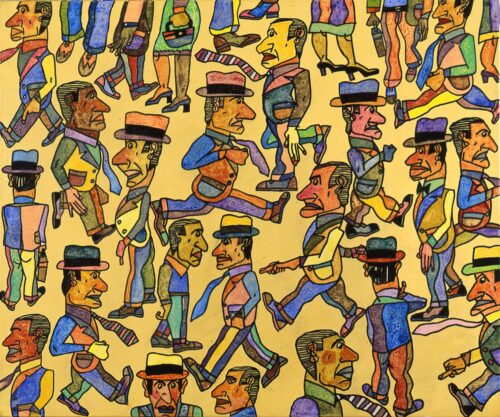

Antonio Segui

The problem is that Simon, for whom, in spite of everything I retained a certain fondness, is taking Brown literally, and in a most prosaic manner. Brown was searching for a method, in a sense. And while some of Love’s Body borders on wilful obscurantism, it has never bothered me much. And the same could be said of Joyce (a favorite of Brown). One must accept with certain artists and thinkers that there is a hidden logic, a hidden vision, that will eventually emerge (or not). Contemporary Academia could do a lot more of prophecy and prophets, of mystics and mysticism, and of poetry. Simon disparagingly says Brown falls between Marshall McLuhan and Habakkuk. Little does he know this is rather a compliment. And if you go google John Simon you will find several late career interview videos of him. Always in a suit. (a nice suit mind you) and hair neatly trimmed. He looks like an insurance executive (or like Wallace Stevens, who WAS an insurance executive) or William Carlos Williams, Eliot Carter or John Cheever even. White wasp rightness. And I confess, because this cultural demographic is so far removed from me, I hold a sort of fascination for it. Brown, unsurprisingly, taught on the left coast, at UC Santa Cruz. Like Marcuse did, further south on the I-5.

The eastern Establishment was never going to approve of any left coast writers or thinkers and if you think that is an exaggeration, you would be wrong.

“Psychoanalytic reconstructions of primitive mental states describe the infant’s fears of “falling forever,” fantasies of omnipotent control and dread of an “endless void.” I suggest that such primitive anxieties represent the result of an evolutionary loss that was visited upon our species as we hovered between non-human primate and human being. It is an essential feature of our species that we must turn away from the concrete in favour of a metaphoric engagement with self and other.”

Josie Oppenheim (From Primitive Fears to the Safety of Metaphor)

Now allow me a final quote from Simon here, which quote is entirely about himself (button downed insurance salesman, remember):

“For,like McLuhan, he fulfills the four requirements for our prophets: 1: to span and reconcile, however grotesquely, various disciplines to the relief of a multitude of uneasy specialists; 2: to affirm something, even if it is something negative, retrogressive, mad; 3:to justify something vulgar or sick or indefensible in us, whether it be television addiction or schizophrenia (McLuhan or Brown); 4: to abolish the need for discrimination, difficult choices, balancing mind and appetite, and so reduce the complex orchestration of life to the easy strumming of a monochnord.”

John Simon (Ibid)

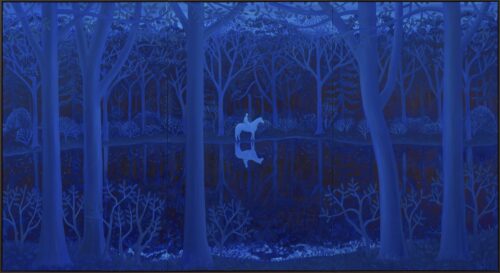

Florian Schmidt

This is why Freud is such a genius. This is Simon defensive about his own feelings. His own difficult choices and his resentments. And Brigid Brophy, in the NYTimes no less, circa 1966, also gets very defensive about Brown’s lack of clarity. And herein lies an allegorical tale all of itself. The NY Times, bastion of establishment truths, and a paper with a long history of lying, openly and unapologetically, must enforce its class codes. The paper, the flagship paper, CAN lie, in fact it has a sort of duty to lie, but you miserable pleb, you cannot lie. Never mind, the point is that Simon writes snidely about everything. He cannot help but write in this tone, because he is writing his own story every time he reviews. That resentful pinched nastiness and sense of emotional control (or constraint or suffocation) is found throughout western society over the last century. Brophy, too, knows her audience. She is writing TO them. Its personal.

“…formal logic and the law of contradiction are the rules whereby the mind submits to operate under the general conditions of repression.”

Norman O. Brown (Life Against Death)

We all think, to a degree anyway, within the constraints of a repressive society, and one defined by the exchange principle, that imposes certain kinds of neurosis. Capitalism is neurotic, but it is also sadistic. Even the sympathetic E.F. Dyck, in his essay, asks for arguments and looks to build a rational construction out of Brown’s work. That somehow the writing of Brown must contribute to this other writing, his own or someone else’s, as the product of Brown’s books. That all thinkers, all theoretical texts, must produce (interpretation) an *other* work, another text, a reflection or mirror of the original. That is the LAW. That the purpose of writing, in fact, is to manufacture an ‘other’, a reflection of itself, and that without this the original will cease to exist in some fashion.

It is interesting to go back and read Brown today, for his style and vision are a greater distance from the mainstream then they were in the early 60s. And I am seeing now, a massive backlash against post structuralism (in the name of a new politics, though largely this is pure marketing I am afraid) and by extension this backlash drives the cultural atmosphere even further from Brown and Freud and Marx. And the difference is much of this new revisionism claims to be Marxist (even if only by implication) but it is never NEVER Freudian. Now, Brown’s importance is not in any sort of system or project (Marcuse wanted, I think, a project formalized somehhow) but in a sensibility and tone, a poetics — a philosophical poetics.

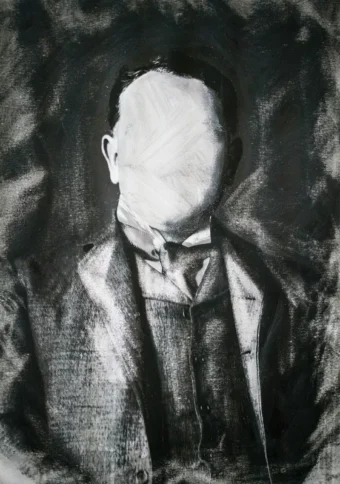

Stefan Peters

Writing of the reception to Love’s Body:

“Translogicality does not deny logic; it simply goes beyond logic. An important example, for Brown and for this essay, involves the law of contradiction. To be illogical would be to assert that “p and not-p” (the negation of “p or not-p”) is universally valid; to be translogical is to assert that “p and not-p” is sometimes valid.”

E.F. Dyck (Ibid)

Brown was looking to escape from the coercive thought of capitalism, really.

“He returns to this idea later—”A reversal of meaning: the symbolism suddenly understood” (217)— and makes a distinction between conscious and unconscious symbolism. “In conscious symbolism the alienated spirit returns to its human creator”; “In bodily experience, in the incarnation of symbols, it happens for the first time as real”; “In the incarnation of symbols we move from allegory to eschatology, from eternal recurrence to eternity” (227). Conscious symbolism uses the body as symbolic referent. In contrast, totemism is “the very act of unconscious symbol formation”; “Allegory, discarnate symbolism, unconscious symbolism, is the world of eternal recurrence, the world of karma, the repetition compulsion” (227). Unconscious symbolism has the body as symbol. Thus, the vague outline of “body symbolism” in Life Against Death achieves here its full shape: the natural, symbolic activity of the child described there.”

E. F. Dyck (Ibid)

This was a key insight. Children do not insist on p or not p. Everything can be both. Children, in a sense, live in a totemic universe in which the repetition compulsion is not yet pathologized. Edward Said reviewed Brown’s third book, Closing Time for the N.Y. Times, in 1973. Said embraced Brown’s ideas and praised the author throughout. And it makes sense Said would appreciate this work.

“To understand history one must trace back civilization to the primitive giants who roamed the earth after the flood; giants from whom we have all come, to whom our cycle is returning us, and with whom we are even now closing. “

Edward Said (Closing Time, NY Times 1973)

Said concluded his review by stating Brown was formulating original forms of knowledge. And this is, I think, the best description of Brown.

Ben Sledsens

The point here is that the current state of western society is one bereft of poetics. I feel this more every day, in fact. And the truly pathological millionaire and billionaire class, few if any elected democratically, are pushing agendas that are intended to eliminate the final traces of humanness and culture. Either through imperialist wars, or genocides, or under the guise of *climate emergency* the European and North American ruling class desire only their own survival. They seem to have no idea of the world they want, except that you and I will not be part of it. They seem unable to imagine the stark boredom and emptiness of the Utopia they dream about. A planet with all but other billionaires living on it (along with camps of slaves, for routine labor or sexual service). In this sense Gaza looms as the model for this arid soulless future. There is at least a semi human sensibility at work in Russia or China, and certainly the real promise, however fragile, lies in Africa and parts of South America. Perhaps in parts of Asia, too.

As an aside of sorts, I wanted to touch on a 2007 article by Eliot Weinberger in the NYRBs, on Susan Sontag. For Sontag looms — because of her severe limitations but unlimited fame, as a sort of bellweather for many of the cultural problems of today (John Simon mentions her favorably). Without wanting to go into a full examination of Sontag, suffice it to say her affinity with Empire was clear (far clearer than it was for Joan Didion, whose saving grace was actually a much keener critical skill) and her Sarajevo stupidity (the Beckett non production during wartime) was mirrored later by her longtime partner photographer Annie Leibovitz and her Vogue photo shoot of Zelensky and wife, also during, eh, wartime. But Sontag had her virtues, certainly. And one of them was recorded by Weinberger…

“Sontag had been one of the first American highbrow literary critics to write on the movies (“the art of the twentieth century”—her italics) and her example had paved the way for the strange idea and practice of the incorporation of Film Studies into the English Department. But by 1995, marking “A Century of Cinema” in Where the Stress Falls, she was lamenting the passing of a golden age of cinephilia in the 1960s and early 1970s—which was of course her period of intense moviegoing—and its “profusion of masterpieces.” She complained that “one hardly finds anymore, at least among the young, the distinctive cinephilic love of movies” (which seems completely untrue) and concluded: “If cinephilia is dead, then movies are dead.” In 1979, writing on Hans-Jürgen Syberberg, she claimed, somewhat ridiculously, that “lately, the appetite for the truly great work has become less robust.” Twenty-one years later, her essay on Sebald began: “Is literary greatness still possible?””

Eliot Weinberger (Notes on Susan, NYRB)

Mikhael Subotzky, photography.

Of course Sontag is mostly right and Weinberger wrong. Weinberger is wrong when he thinks the young, even the film school young, love films the way cinephiles did in the 70s. I know, I taught at the most famous film school in the world (The Polish National Film School in Lodz). I did it for nearly 8 years. And I have, myself, asked if literary greatness is still possible? I think it is, but its hard to know since we don’t see it. Or haven’t seen it yet. Not for a long while. But this begs the question what society wants, overall, from art. From contemporary art. That billionaire class doesn’t care, certainly. Anyway, Sontag was mostly pretty accurate in her tastes; Artaud and Pavese, Roland Barthes and Paul Goodman, Juan Rulfo, Syberberg (and not many did or do), Fassbinder, and yes, Norman O. Brown. She had a number of dubious ‘likes’, though, too but most everyone does. Her short essay on Camp, included in Against Interpretation (1966) was oddly influential (for me, too). It was an original insight, however ultimately slight. And her later work is pretty forgettable (contra Weinberger). She was a brie and chablis New York elite and she never strayed from that.

“John Berger’s Ways of Seeing BBC TV programme, and the subsequent book published in 1972, shaped the way a whole generation ‘saw’ images and the way they are embedded in the culture surrounding them. Berger averred that we see before we can speak, as any observer of infants will know. We explain our world with words, but words are what we ‘invent’ to talk about what we see. There is an ever-present gap between words and what we see; what the developmental psychologist and psychoanalyst Daniel Stern called ‘slippage’ (Stern, 1985). Berger placed the art and skill of observation at the centre of all his thinking. I suggest here that this skill lies at the heart of all our endeavours. Berger thought (and I think many in my profession, child and adolescent psychoanalytic psychotherapy, would agree) that if you look long and hard at anything it will either yield its secrets or, failing that, enable one to articulate why the withheld mystery constituted its essence. “

Judith Edwards (Psychoanalysis and Other Matters)

Mario Macilau, photography (Mozambique)

I remember theatre director Ariane Mnouchkine once said, if you watch your dog in the backyard, from your kitchen window, and you watch for an hour, it seems perfectly natural and real. If you watch it for nineteen straight hours, it will be unrealistic. (I paraphrase). I told this often to students in theatre classes. But it is the same with listening. Or almost the same. This raises the very neglected topic of memorized text on stage. And of speech in general. We listen to the world. We listen to speech. And it is different. Words and language are so hugely mysterious, finally. Children pick up new languages far faster than adults do. Why is this?

Berger was a corrective of sorts to Sontag. But looking back at the second half of the 20th century it is easy to see a critical class of public intellectuals; from Berger and Sontag to Trilling and Debord and McLuhan and Norbert Weiner. I could go on, of course. It is maybe telling that few science writers were at all prominent. Maybe Stephen Jay Gould, but he was never hugely popular. And the reason is that science came to be too specialized and perhaps too pointless for many. It existed at some distance from daily life. Still, there was a climate of legitimate intellectual discourse. And today there is nothing. Quite literally what amounts to nothing.

But to return to speech on stage. In our age of the teleprompter, the idea of public speaking has lost clarity. Political debates are not debates at all, as everyone knows. Marketing eclipsed public debate. Marketing came to control everything. And television came to be an organ of marketing. Marketing became the entire culture of the West. Literally everything, by the 80s, was pre-fabricated.

Nikolaos Schizas

“Observation is not a skill confined to those training as psychoanalytic clinicians. It’s one which is also practised across the spectrum of the creative arts and the sciences. ‘Being there’ is a vital component of witnessing what goes on in any observational

transaction, be it between hand, mind and external object, or in psychoanalytic observation between the observer and the observed environment, with the infant placed centre stage. It has of necessity a great deal of heart as well as mind in it; empathic observation can’t be practised by a disinterested or dissociated observer. I’ve had the privilege to participate as a seminar leader in many groups of students, observing many babies. This is how future clinicians fine-tune their responses, learning much about how to unlock what might be called the existential codes of all beings, while observing the development of just one. The ‘personal style’ of babies can be seen to emerge in observations over time, as they use these universal ‘codes’, seen from a psychoanalytic point of view to be locked in unconscious processes such as splitting, integration, anxiety, guilt, denial and reparation (to mention just a few). Observing a baby is essentially also a kind of self-education: clearly seeing how things are without preconceptions, as A.C. Grayling (2002) wrote about educating the self. True seeing can then take place.”

Judith Edwards (Ibid)

There has been both an overt rewriting of history going on, and a covert and maybe even unconscious (sort of) rewriting. And intersecting with this covert revisionism is the role of science. (side bar: see the restoration of Jan Van Eyck’s alterpiece in Ghent. The so called mystical lamb. The alteration was done with lots of AI help, and X-rays and experts have now spent years on the project. The result …at least the lamb’s face, is a cartoon. Now the painting was started by Jan’s less talented brother Hubert. And experts actually ended up scraping away Jan’s work and leaving a sort of hybrid lamb, part Hubert and part Jan. The problem is Hubert was a pretty shit painter compared to his baby brother.But my point is technology yet again has had a disastrous effect. Common sense should tell you, and the ability to LOOK at the painting, that the direction of the restoration was badly conceived). Science seems to be used in some strange ahistorical manner, or imagined, scientific method, as outside of time, and modern science can bring the past up to the present without problems.

Jan van Eyck, 1395.

This was part of a graduation speech Brown gave at Columbia, in 1960.

He continued: “Mysteries display themselves in words only if they can remain concealed; this is poetry, isn’t it? We must return to the old doctrine of the Platonists and NeoPlatonists that poetry is veiled truth; as Dionysus is the god whois both manifest and hidden; and as John Donne declared, with the Pillar of Fire goes the Pillar of Cloud. This is also the newdoctrine of Ezra Pound, who says: “Prose is not education but the outer courts of the same. Beyond its doors are the mysteries. Eleusis. Things not to be spoken of save in secret. { } And second, mysteries are unpublishable because only some can see them, not all. Mysteries are intrinsically esoteric, and as such are an offense to democracy: is not publicity a democratic principle? Publication makes it republican— a thing of the people. The pristine academies were esoteric and aristocratic, self- consciously separate from the profanely vulgar. Democratic re-sentment denies that there can be anything that can’t be seen by everybody; in the democratic academy truth is subject to public verification; truth is what any fool can see. This is what is meant by the so-called scientific method: so-called science is the attempt to democratize knowledge— the attempt to substitute method for insight, mediocrity for genius, by getting a standard operating procedure.”

Norman O. Brown (Ibid)

Now, this is a pretty curious paragraph at first glance. But Brown was of the belief that civilizations begin with the revealing of a mystery, a sacred mystery. And end in exhaustion when there is nothing left to reveal. And so, we enter a time demanding new mysteries. Now I referenced two or three times the Gramsci quote about living in the interregnum, before a new system emerges. In one sense this is the same idea, we live in this time of exhaustion but also of absence. We are the people of departure. (contra Neanderthals and early homo-sapiens, who Berger saw as the people of arrival, which Ive also referenced several times). Society is already in a new dark age. The U.S. presidential election confirms this.

Slim Aarons, photography.

The desire to colonize Mars is an allegory made material by the insane transference of wealth to a top half percent. The symbolic becomes literal. And it is here that I want to return again to human origins. And to our concept of time and the past. Our closest ancestors, probably a million years ago, evolved into Neanderthals, so it seems, and a bit later, but overlapping, early homo-sapiens. They cross bred. But for literally hundreds of MILLIONS of years before that there were creatures roaming forests and grasslands all over the planet. The sense of time is so immense that the mind freezes up. I have written about some of this before, but it is worth looking at from new angles. Sponges to crabs to apes.

“ In purely anatomical terms, we can ‘see’ Neanderthals emerging slightly earlier at the Sima de los Huesos than the oldest H. sapiens-like fossils from Africa around 300 to 200 ka, a temporal gap filled by thousands of generations. But in broader evolutionary terms, they’re one of the very youngest hominin species, and extremely similar creatures to us.”

Rebecca Wragg Sykes (Kindred)

Neanderthals looked a good deal like us, judging from skeletal remains. They were shorter, on average, with shorter legs. There are a host of intriguing anatomical details that differ, many of which seem inexplicable. There teeth were set in their jaw differently, and they had tinier ear bones, but much larger eyes. And probably, at least some of the Western European Neanderthals had red hair and freckles. They had much wider nostrils but it is unclear, apparently, what purpose this served. But since they inhabited a more northern climate, often at higher altitude, those large eyes served them well in scanning the horizon.

“If their vision was perhaps more acute and their hearing just as sensitive to voices carried on the breeze, what was their experience of smell? In 2015 a perfume called ‘Neandertal’ was released,claiming to be inspired by the ‘hot flint aroma’ produced from making stone tools. Remarkably, this isn’t just sales-speak: snapping flints does produce a distinctive scent. It’s often compared to a fired gun, and is exactly how astronauts described the smell of moon dust. Around half of the talcum-fine lunar surface is asteroid-pulverised silica: the main ingredient in flint, quartz and other commonly knapped rocks. Strange to think that moon-tang would have been more familiar to a Neanderthal than to Neil Armstrong. However, while Neanderthal visual systems were enlarged compared to ours, their olfactory bulb – the brain region that deals with scent – was reduced. Interpreting that as lesser sensitivity, however, requires caution, and it’s here that once again genetics comes in. Though not identical, there’s clearly some overlap in scent-detection genes between us and Neanderthals. One molecule, androstenone, is intriguing. It contributes to the ‘perfume’ of human sweat and urine, and among the roughly 50 per cent of living people who can detect it, strong dislike is one reaction. If some Neanderthals could also detect this odour, maybe it had a useful function. Androstenone affects hormones and emotions in people, but it’s also given off by wild boar, and smelling the porcine version has a dramatic effect on dogs. Perhaps it’s involved with hunting: being able to smell a herd over the hill or detect that an animal had passed by would have had strong advantages. Whatever the specifics of particular odours, though, Neanderthals very likely experienced smells – pine resin, horse sweat, old smoke – as a strong trigger for memory.”

Rebecca Wragg Sykes (Ibid)

Lou Ros

Neanderthals spent a good deal of time working hides. Scraping and pulling, often with their teeth. They were right handed, like us. And had very powerful hands. Meanwhile, there were other close relatives populating the earth. Neanderthals largely lived in caves, lived in family groupings and cooked around a hearth. They ate birds and fish (and it seems a lot of tortoises) and some plants. They ate some big game which they hunted with spears. And they slept on grassy mats of some kind, from all evidence. Forty thousand years ago, miles outside Paris, were found both h.sapien and Neanderthal inhabited caves with sandstone blocks. Sort of Neanderthal furniture. All indications the Neanderthal (and h.sapien) community ate off them. They sat on small blocks and ate from the larger blocks. They were remarkably like us. There is no way to know the total global population of all homo sapiens and Neanderthals. Guesses range from ten thousand to a hundred thousand. Meaning not many. Some postulate much higher numbers but its likely we will never know. It is safe to say for the people of arrival it was an empty world. A vast mysterious and empty world. It was highly unlikely that you ever met another of your species outside of your clan. For tens of thousands of years.

And this is the thing, for me, when I consider these details. The span of time.

“Neanderthals were fundamentally nomadic. Their world was the land, and moving in it was life. Like everything else they did, this was far from random. Sites were not simply destinations, but intersections, nodes within networks stretching hundreds of kilometres. The blood-stained, fur-tufted muds at a kill site – an ephemeral locale – were nevertheless linked to caves or rockshelters through the animal bodies taken there to be further divided. All places Neanderthals went were connected by their physical movements, and the things they carried. Each new-kindled fire was a glowing pearl in an unbroken string laced across ridges and threaded through forests.”

Rebecca Wragg Sykes (Ibid)

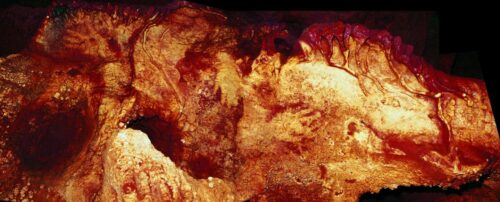

Maltravieso Cave, Spain. Neanderthal hand stencils, 66, 000 years old

And here one feels a question forming. For both early h.sapiens and Neanderthals (and probably, in the early days a couple other variety of ‘us’) lived in primordial communities. There were young, children, teenagers, and fathers. And mothers. How those relationships evolved is a primary question. They returned to those kill sites, often multiple times. Often, it appears, returning regularly for seasonal kills. Memories formed around these locations. As Nomads, earlier Neanderthals probably were just itinerate. Later communities or clans planned their moves. It is estimated 60 km a day was not impossible at all. For some hunter/scouts far longer distances are not unlikely. But the caves at Bruniquel deserves a special mention at this point. (Google it and look at the photos, because it is truly remarkable). These caves have dated Neanderthals there 174 thousand years ago. This is far earlier than most imagined. The built structures are also suggestive of a far more complex mind that first believed. We are moving further and further from the knuckle dragging caveman idea of Hollywood.

“Bruniquel laughs in the face of austere, survival-only explanations for Neanderthal behaviour. It surely was made by thinking, but also feeling, minds. Emotions in reality underlie virtually everything people do, no matter if logical explanations also exist. All human cultures also have a desire for transcendence.

Rebecca Wragg Sykes (Ibid)

Well, perhaps. It is clear Neanderthal brains were moderately different. Less cerebral cortex but larger and more complex visual systems. And it is believed they spoke, and heard things in much the same way. In the Cioarei-Boroşteni Cave in the southern Carpathians geodes have been found, brightly colored in places, that were believed to have been used as vessels of some sort. They are beautiful, by most standards of beauty. These distant ancestors had aesthetics. But the Bruniquel cave remains a spectacular enigma. And because of its age, there remains a good deal of mystery surrounding it. Neanderthals travelled, returned to special sites, and hunted together. They hunted cooperatively. They shared food. They ate together. Teenagers had sex, apparently with *other* hominins as well as their own clan. Its not unreasonable to assume group hunts involved outside bands. Or clans. With prey like Reindeer, whose long migratory journey is fairly predictable, such knowledge would (over, you know, 300 generations) become common. Younger children have left handprints in volcanic mud on mountain slopes, as would children today. And they viewed death with the same mystery and awe and confusion. Neanderthal death rites remain somewhat mysterious, but suffice it to say they ritualized their loss. Probably in various ways in different regions.

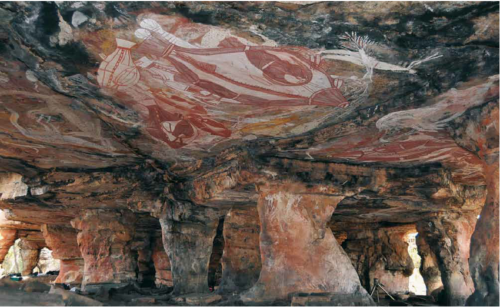

Nawarla Gabarnmang, Australia. 40,000 years ago. (JJ Delannoy photography)

“One of the shortest Neanderthal lives ended around 70,000 years ago, in the Caucasus Mountains. A week or two old at most, it’s astonishingly well preserved. Just “week or two old at most, it’s astonishingly well preserved. Just a whisker above the rock floor of Mezmaiskaya Cave, the tiny skeleton was found lying on its right side, knees flexed, legs drawn up, with its left arm bent slightly towards the chest. It almost appears to be napping. So intact that its minuscule tooth buds were still present, most bones were in the correct position and largely undisturbed, aside from some lower leg parts that probably became loosened when the surrounding hardened sediment eroded. Explaining how this tiny baby was deposited and remained almost undamaged means either another series of special circumstances, or the involvement of other Neanderthals. Such a young baby would be highly unlikely to be forgotten, or simply dumped after death. It’s true that if orphaned young chimps don’t get adopted by other adults, they typically become ill, depressed and die. But even if this was an abandoned body, other questions remain. Newborns typically don’t learn to roll for many weeks, so the side-lying posture is surprising, and though rodents nosed and nibbled the exposed dry leg bones, there’s no damage at all from large scavengers. Moreover, despite no evidence for a pit, compared to the rest of the cave’s lowest layer, the sediments immediately around the skeleton were distinctive. Instead of any lithics or fauna, there were small charcoal fragments lacking elsewhere.”

Rebecca Wragg Sykes (Ibid)

A footnote here; there is evidence for cannibalism among homo-sapiens. In England (I want to say ‘of course’):

“…cannibalism among H. sapiens from various periods in time. Around 15 ka, bones from at least six people – possibly just a few generations of one group – were butchered at Gough’s Cave, south-west Britain. They were processed similarly to – and jumbled among – the hunted animals, but a whopping 65 per cent have processing traces and nearly half also bear tooth marks.”

Rebecca Wragg Sykes (Ibid)

Dan Holdsworth, photography.

This is a fairly recent date, it should be noted. But cannibalism was found in rare cases among Neanderthals. The mortuary practices varied but certainly even the earliest homo sapiens seemed to develop death rituals more formally than did Neanderthals. But the final note here is really two notes. One is about a recently discovered ‘ghost’ population. Neither Neanderthal or Homo-sapien. And it came from Siberia. Allow me a long quote here…

“Unusual freezer-like conditions inside Denisova Cave, in the Altai region of Siberia, opened up a ‘Wild East’ frontier, as DNA there was in exceptional condition. A sample extracted from D5, a toe bone, provided the first ‘high-coverage’ Neanderthal nuclear genome: our introduction to the recipe for another kind of human. Dubbed ‘the Altai Neanderthal’, the toe had belonged to a woman who died around 90 ka. She came from a truly venerable lineage that had separated from others some 40,000 or 50,000 years before. And totally unanticipated, the mtDNA of Okladnikov, geographically nearest to her, was not closest genetically. Instead, it was the newborn baby from Mezmaiskaya, in the Caucasus thousands of kilometres west, who matched best.{ } The genetics revolution has also been the cause of truly astounding discoveries. Denisova is today world-famous not because of the Altai Neanderthal lineage, but because of a minuscule bone: a girl’s fingertip. Known as D3, her mtDNA didn’t match any hominin group, and she turned out to be the accidental ambassador for an entire ‘ghost’ population nobody knew existed. More and more DNA from these hominins existed. { } “What were Denisovans like? For nearly a decade researchers had only the barest hints of their appearance. DNA indicates some had brown eyes, hair and skin, and their teeth weren’t identical to Neanderthals’. But other physical remains are so limited – the D3 fingertip plus three teeth – that not much else could be said. In 2019 researchers tried to ‘reverse engineer’ Denisovans by looking at unique aspects of their genes involved in body growth. Although we won’t know for sure until (if) we find skeletons, their heads may have been even wider than Neanderthals’, and fingers also longer. { } “Everything points to Denisovans as an Asian species. Remarkably, proteins from a jawbone at Xiahe, high on the Tibetan plateau – and 2,200km (1,370mi.) south-east of the Altai – are either Denisovan or from a close ‘sister’ population. But we also know they and the Neanderthals lived in the same cave, albeit at different times. Did they ever meet? The answer is a resounding yes. Tantalising hints in D3’s DNA suggested her ancestors had at some point interbred with Neanderthals, but the real shocker was yet to come. Re-enter D11, the tiny limb fragment from a young teenager who had lived around 90 ka. It had originally been found in 2012 and only recognised as hominin via protein sampling four years later. D11’s mtDNA placed her as a Neanderthal, but this came only from her mother. Her nuclear DNA instead showed her father had been Denisovan. ‘Denny’, as she was nicknamed, is the only first-generation hominin hybrid ever found. So improbable that the researchers did not initially believe it, the implications are staggering. It was assumed that interbreeding was rare, and direct evidence would only ever lurk in the genetic gloom, many generations back from the from the bones we study. Actually finding the child of a union between different kinds of hominin implies it can’t have been that uncommon. In fact, Denny’s DNA contained vestiges of yet more interbreeding. At least one of her father’s ancestors had encountered Neanderthals too, albeit thousands of years and many, many generations before. In a last surprise, this ancient Neanderthal ancestor wasn’t from the same genetic population as Denny’s mother. She was part of the eastern twig of the European lineage, also found at Okladnikov. In contrast, the Neanderthal ancestry in Denny’s father connected much further west, to the El Sidrón-Feldhofer-Vindija grouping. Everything at this remarkable site makes it abundantly clear that, far from being static, these hominin populations saw huge flux over time.”

Rebecca Wragg Sykes (Ibid)

The second point is that the ‘people of arrival’, even from the earliest Neanderthal and h.sapien dates, 160 thousand or so years ago, existed in more complex societies than previously imagined. From what is now Tibet and Mongolia to the south of Spain, across the Pyrannes and in southern England, nomadic ancestors lived and slowly evolved practices and beliefs. Across the Malay peninsula, in Australia, in China different groups of related DNA, were doing much the same thing. And they somehow found other groups and bands, and interbred. And some large groups died out. Others merged. And how does Rene Girard or Freud apply here. What did Neanderthals dream? Or desire? That there are so many sites where it is evident early Neanderthal children played, in small groups, suggests these were happy people. To some degree. They ate together. They painted cave walls together. And for generations in some places they painted over earlier paintings. Sometimes for thousands of years. And this is what I want to point at most specifically: our society is a couple thousand years old. And clearly unique. But we also suffer enormous hubris, I think. We do not know how to grasp a time span of 300 generations. Or 500. It is difficult to understand five thousand years where nothing seemed to happen. Five or ten or twenty thousand years of the small migratory movement, seasonal group hunts, children. And what of those caves.. deep inside mountains, barely accessible, where something happened. Something. Is this is the origin of aesthetics? Theatre? Religion and God?

Donald Judd

In my play The Shaper, the last line, as the lead character staggers back on stage…from ‘somewhere’….he says ‘something has happened’. This was the allegory I didn’t know I wrote. Something, somewhere, out there, happened. And it happened a number of times and we are still trying to learn what is was.

To donate to this blog use the paypal button at the top of the page.- Donations also go to keep the Aesthetic Resistance podcasts going.

https://open.substack.com/pub/aestheticresistance/p/podcast-134?r=12qzc&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=true

The ghost population trapped and programmed by/in the collective Wetiko psychosis of death as described by Paul Levy have just elected their chosen “savior”.