Tony DeLap

“The lion griefs loped from the shade

And on our knees their muzzles laid,

And Death put down his book.”

W. H. Auden (A Summer Night, 1934)

“The mind has added nothing to human nature. It is a violence from within that protects us from violence without. It is the imagination pressing back against the pressure of reality. It seems, in the last analysis, to have something to do with our self-preservation; and that, no doubt, is why the expression of it, the sound of its words, helps us to live our lives.”

Wallace Stevens (The Necessary Angel)

“It was not from the vast ventriloquism

Of sleep’s faded papier-mache…

The sun was coming from the outside.

… It was like

A new knowledge of reality”

Wallace Stevens (Not Ideas About the Thing, But the Thing Itself, 1954)

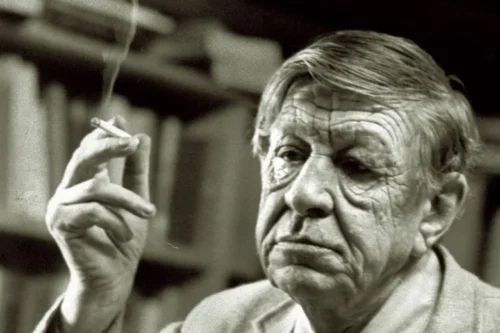

I found myself thinking this last week about Auden. And about poetry. I have no idea, really, what brought this on but like any even relatively educated human there are plenty of reasons to think about Auden, and about poetry. (I have told the anecdote before about having catalogued Auden’s library back in the 70s in NYC and how just last year I got a wonderful inquiry, in email form, asking if I was indeed the young man who did the cataloguing. And the writer of the email thanked me and wondered about some details. Said I had done a excellent and thorough job.) Anyway, I remember there was a lot of history and not a lot of poetry. But the point here is that I never really read a lot of Auden. The Dyer’s Hand, a collection of critical essays, I read and used often in teaching. Its very good and a sort of model of what critical writing should achieve. But while I appreciated his poems I was not moved by them. I did not find that generation of English poets terribly interesting. But now, now I find Auden a good deal more interesting. I still do not love (emotionally) his poetry, but I admire it even more.

I think as one gets older Auden becomes more relevant. Also, one’s tastes change and that is my topic. Not that I even think Auden is one of the century’s great poets. I would say, if gun was to head, he IS, but he’s not in my canon. Cesar Vallejo is, and James Wright, and Lorca and Neruda and Bly, and probably even Robert Lowell. And Roethke, certainly and Stevens. And William Carlos Williams. But Auden is more, as he once said of Freud, ‘a climate of opinion’. Auden is something like that, not of opinion but of culture. Auden was a lot more visible to the public than someone like Lowell, he was in his way the Gore Vidal of letters for his time. Both men were gay, were highly articulate and carried a certain legitimate authority, culturally speaking. Vidal was more political, overtly. Both were privileged.

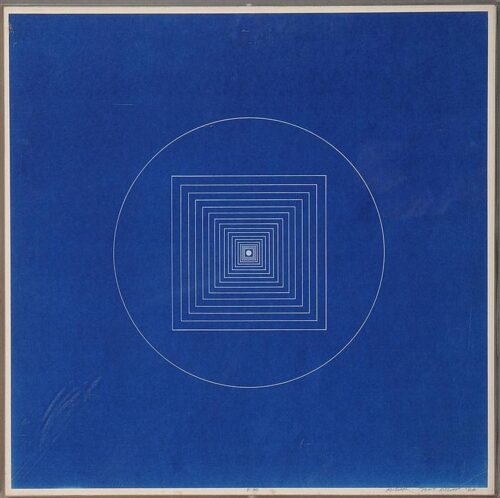

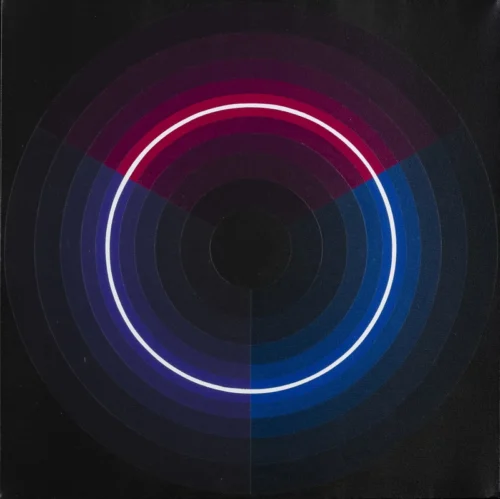

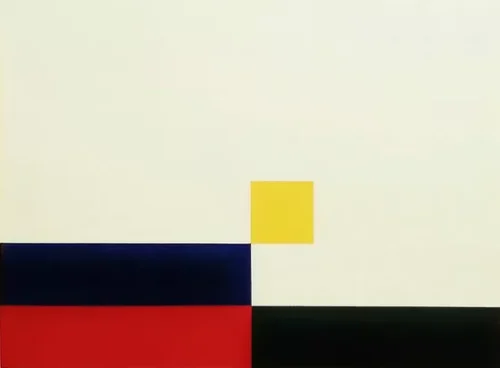

Pat Lipsky

“I want to explore the relation between the kind of poetic authority which W.H. Auden sought and achieved and what might be described as his poetic music. By ‘poetic authority’ I mean the rights and weight which accrue to a voice, not only because of a sustained history of truth-telling, but by virtue also of its tonality, the sway it gains over the deep ear and, through that, over other parts of our mind and nature. By ‘poetic music’ I mean the more or less describable effects of language and form by which a certain tonality is effected and maintained. I shall listen in to some passages of Auden’s work and try to describe what is to be heard there; I shall also try to follow some of the echoes which the passages set up and ask how these echoes contribute to the poetry’s scope or suggest its limitations.”

Seamus Heaney (Sounding Auden, London Review of Books, 1987)

Edward Mendelson, in his lengthy and exhaustive study/bio of Auden, wrote of the child Auden and his fantasy world. “‘I decided,’ he { Auden} recalled, ‘or rather, without conscious decision, I instinctively felt that I must impose two restrictions upon my freedom of fantasy.’ In choosing the objects that might go into his private world he must choose, he said, among objects that really exist; and ‘In deciding how my world was to function, I could choose between two practical possibilities—a mine can be drained either by an adit or a pump—but physical impossibilities and magic means were forbidden.’ He felt, ‘in some obscure way, that they were morally forbidden,’ that the rules of his game must represent both the laws of nature and the laws of ethics. Eventually, still during childhood, ‘there came a day when the moral issue became quite conscious’.”

Edward Mendelson (Early Auden/Later Auden)

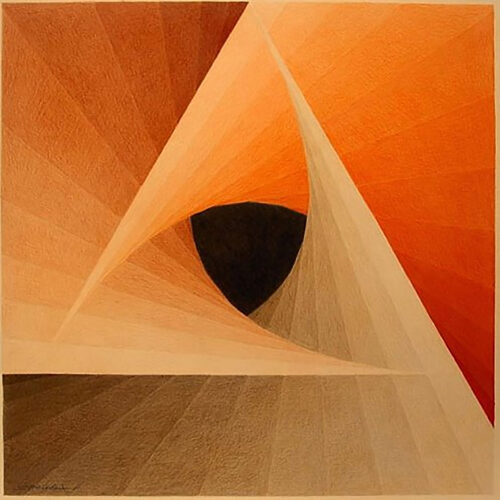

Zanis Waldheims

Poetic authority, yes, one could say cultural authority. Aesthetic authority. Auden was a serious artist and critic. It may be that Auden came to mind just now because of the dearth of public visible artists of any kind. Who are the poets commenting on Gaza? Western poets. English language poets. I can’t find any. European poets? There may be some but I cannot find them. What about just writing on Imperialism, on capitalist war and occupation? Nope, I can’t find any. Even indirectly. Now poetry needn’t be political in a direct way, but great poetry, even any serious real poetry carries a political import. One of Auden’s kitschier poems was his Sept 1, 1939. But while not among his better work (he later called it rubbish and disowned it) it was still addressing something in the zeitgeist, the fascist unconscious he sensed rising around him. Worth noting: “Writing to the Scottish novelist Naomi Mitchison, he grumbled, “The reason (artistic) I left England and went to the U.S. was precisely to stop me writing poems like ‘Sept 1 1939’, the most dishonest poem I have ever written.” In particular, he hated the line “We must love one another or die,” remarking, “That’s a damned lie! We must die anyway.”

Spencer Lenfield (Journal of the History of Ideas)

There are no poets today, in the U.S. that carry any authority. (here are five nominated by the Harvard Crimson https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2019/4/23/best-contemporary-poets/ ) Appalling bad, every one of them. I ask you, please, read a poem by each of them and get back to me. I would gladly accept a bad Auden poem right now.

The five Crimson poets are stunningly bad. But all ‘are’ woke, certainly. None are political even by teleportation. Bly is dead, Merwin is dead. Many of the best American poets of mid century died in the late 70s. Wright in 1980, Lowell in 77. Zukovsky in 78, and Olson in 70. Merwin and Kinnell, Louis Simpson, and Bly only in the last decade. Gary Snyder is still alive at 94. The greatest living English language poet almost certainly. Robert Duncan died in 88. Creeley in 2005. Each mentioned above were of a certain generation, of sub generation. Duncan was an important teacher and influence if not a great poet. He was a minor poet. Olson was major, Wright and Bly major. Merwin almost major, but not. Creeley was terrific, and an influence, but not a major poet finally. Wallace Stevens and Roethke were a generation earlier. And Stevens, Williams, and Roethke were all major. (Stevens died in 1955, Williams in 1965, and Roethke in 1963). Auden was English, and after he and Eliot it is hard to name a major 20th century British poet. Empson was a brilliant critic but not a brilliant poet. Pinter a genius playwright but not a brilliant poet. Dylan Thomas is appealing but decidedly minor. Ted Hughes is close-ish, but more a great critic and teacher. There is Heaney, Irish, and he maybe is major but I think not. Michael Ondaatje (Canadian/Sri Lankan) is really very good, but is not major. But also profoundly underrated, I think. Anne Carson (Canadian) is good but perhaps a better teacher and essayist. But Carson is certainly a poet of genuine depth and intellect. Yeats was major certainly. But looking back one has to reach to the generation of Keats, Blake, Wordsworth, Coleridge, Byron and Shelley. And nothing since comes close (in England). Why is this? Laurie Smith suggests the first reason was Rousseau and the American and French Revolutions. A sense of individual greatness. And…

“The second source of great poetry was, paradoxically, a limited education in English literature. Eighteenth century education was extraordinarily permissive by later standards. Boys who received formal education were sent to day or boarding schools chiefly to learn Latin and, if they were able enough, Greek together with such arithmetic as was necessary for daily life. Almost the only English literature taught in schools was Shakespeare and Milton, and the Bible was read at Sunday service. Having undergone such an education, the boys (and their sisters who were normally educated at home) were free to read whatever their father’s library contained or could be borrowed from friends or the new lending libraries, at a time (it is hard to imagine) when almost no reading was necessary. For bright boys, Rousseau’s Confessions were more interesting than collections of sermons or practical treatises on estate management.”

Laurie Smith (The New Imagination)

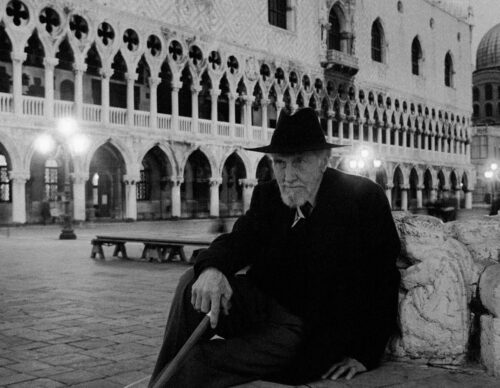

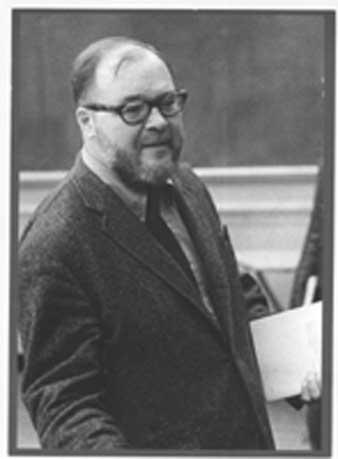

W.H. Auden (1969)

There is a Navajo poet, Shonto Begay, who is worth reading, I think. It is better to hear him read because his work is really reportage. A graduate of US *Indian* boarding schools, there is inherent gravitas to his voice. Most new American poets, MFA poets, have a trivial quality to their work, all of them, and a narcissism. White narcissism and the poets of color (sic) are the most narcissistic and the whitest.

William Empson wrote wrote Seven Types of Ambiguity when he was 24. (Empson died in 88). Something significant has gone out of western society and culture and it began in the 1970s. Maybe it really began right after WW2, but was still a small thing. A small momentum of unravelling, culturally. A liberalism that took wrong turns on discernment. This tendency to award participation was one aspect. The famous ribbon for taking part. Somehow that ended with men beating up women in the Olympics. Of course running alongside this was the ascension of science as a religion. Instrumental thinking and the effect this has had on language. And on imagination. And this is obvious and hardly debatable. The language of the World Bank (per Moretti). But Academia itself has become a horrible influence. A terrorizing Kafka like career Castle. Poetry in the age of texting or Twitter (X) is ever more difficult. I think when one says ‘major’, it means everyone has to read this poet. You have to read Stevens. He is, probably, the most important English language poet of the century. You have to read Stevens. Like you have to Marx, Freud, Melville, and Kafka. And probably Wittgenstein. THEN you can go back and read what grabs your attention. Read the Greeks. Read Dostoyevski and Pinter and Handke. You get the idea. I think it was Henry Miller who said read your close contemporaries first. Then go back and start at the start. In other words its better to read Wallace Stevens first and Dante second, rather than the other way round. And eventually you come to Shakespeare and the King James Bible.

“A movie again would emphasize the particular furnishings on the galley, but it doesn’t matter if it’s a galley or a house. What matters is the view it presents of the lords of the world in undress in contrast to the scene of Ventidius and his troops guarding the frontier. Space is the prize, and not any particular corner of space, but the whole space of civilization.”

W.H. Auden (Lectures on Shakespeare, Anthony and Cleopatra)

This sounds a bit like Charles Olson writing on Melville. Now I write from the perspective of an American. For the English, there are a different set of problems.

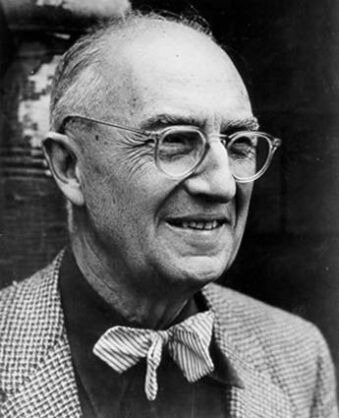

David Hockney

“I have argued that the poetic imagination has been stifled in Britain since the 1830s by an education system ruthlessly designed to produce efficient administrators and business managers. “

Laurie Smith (Ibid)

At this point the question turns to what a society wants from art. And it is a complex question. Maybe it doesn’t exactly matter what society ‘wants’. Poetry is not for mass consumption. It has always been something that matters to a very few. The influence of poetics in general then, sifts downward. But that sensibility that great poets bring to society has importance. One of the problems on the left has been the idea, often almost unconscious, that art is there to instruct. Art does something very different. And what it does is so bizarrely complicated and illusive that mass opinion is never going to really care. And the left confused class war with an idea that elite appreciation was reactionary. Liberals embraced the idea of popularity as a criteria. You get op ed pieces arguing Fred Astaire was the greatest artist of the century. That Norman Rockwell was just misunderstood and was actually brilliant. And so on. Now what Debord called ‘The Spectacle’ interceded at this point. And the new digital mass culture soon eclipsed most everything else. Hollywood and this idea of ‘entertainment’ was taken seriously. All this has been charted pretty thoroughly.

Still, the absence of major work today is worth discussing. Assuming you agree that there is an absence. And I think it is useful, when examining the process of education here, personal education, to look at both Ezra Pound and Stevens (and maybe Williams. I confess to deep affection for Williams that makes me a bit biased). But Pound looms over all American arts and letters in the 20th century. Pound was born in 1885 in Idaho (but raised in Philadelphia). Died in 72. And Pound looms over all of not just poetry but American arts and letters for most of the 20th century.

Gerhard von Graevenitz

Hugh Kenner’s essential The Pound Era, begins with Pound (and his wife’s) visit to Henry James, June 1914. The first World War was to begin soon. And James would be dead in a mere two years. Kenner writes….“They sharpened the officers’ swords on August 7, for brandishing against an avalanche. “The wind of its passage snuffed out the age of unrivalled prosperity and unlimited promise, in which even poor mediaeval Russia was beginning to take part, and Europe descended into a new Dark Age from whose shadows it has yet to emerge.” Within three weeks Louvain’s 15th-century Library had been rendered blackened stone and its thousand incunabula white ash, in a gesture of admonitory Schrecklichkeit. { } Henry James to his own last admonitory gesture: a change of citizenship. It was no more understood than The Golden Bowl had been. The next January he was dead of apoplexy, and to Ezra Pound not only a life but a tradition seemed over, that of effortless high civility. Not again . . . not again . . . , ran an insisting cadence, and he made jottings toward an elegiac poem on the endpapers of a little book of elegies called Cathay. “Not again, the old men with beautiful manners.”

Hugh Kenner (The Pound Era)

Pound was to ruminate on James often over the years. For those men with beautiful manners would not come again. Manners as (per Kenner) a synecdoche for ‘custom indicating high culture’. And Pound was to sense with remarkable sensitivity the allegorical implications of inverted commas and semi colons, quite literally; the way people talked, and listened. He watched ‘society’. The philosophical meaning, social meaning, even political meaning of the pauses in Henry James, suggested moral reflection. Moral rumination. Pound was to find the lexical meaning in Confucius too.

“What Confucius has to say about style is contained in two characters. The first says ‘Get the meaning across,’ and the second says ‘Stop’.” And on being asked what was in the character “Get the meaning across,” “Well, some people say I see too much in these characters”—here a good-natured glance at ambient lunatics—“but I think it means”—the Jamesian pause—“‘Lead the sheep out to pasture.’”

Hugh Kenner (Ibid)

Cleon Peterson

Eliot’s famous remark that James had ‘ a mind so fine so idea could violate it’. But this had deeper implications, too, besides wit. Eliot saw, like Pound, the already bastardizing of the English language. Pound was corresponding with William Carlos Williams by the early 1900s. And finally, after Thanksgiving 1911, spent with Williams, Pound sailed for Europe. Not to return for thirty years.

Kenner picks 1904 to juxtapose some timelines…Ford Motors was founded, the Wright Brothers flew (for twelve seconds), Henri Poincare delivered a lecture at the “International Congress of Arts and Science” on a theory of relativity, as speculation. Einstein, then 25, would write his theory on this idea a mere nine months later.

“The previous year, one evening after dinner at the White House, he and a visiting lecturer, Ernest Fenollosa, had recited in unison “The Skeleton in Armor.” Salient Parisian happenings were less public. On a washerwoman’s barge near the Rue Jacob, Pablo Picasso, 23, was coming to terms with his new city and commencing to specialize in blue. In the Rue Mouton-Duvernet Wyndham Lewis, 22, about to ship laundry to his mother in England, was fussing about the customs documents (“must I declare them dirty?”). In what was still St. Petersburg Ivan Pavlov received word of a Nobel Prize for his work on the physiology of digestion, and Igor Stravinsky the judgment of Rimski-Korsakov that his talents were less well suited to law than to music. The Psychopathology of Everyday Life appeared that year in Vienna (and Peter Pan in London). In Dublin there was much action. The Mechanics’ Institute Playhouse and what had been the adjoining city morgue were connected and at year’s end opened as the Abbey Theatre. On June 16 a man who never existed wandered about the city for 18 hours, in the process sanctifying a negligible front door at 7 Eccles Street. ”

Hugh Kenner (Ibid)

William Carlos Williams

Louis Simpson (Three on a Tower)

This period prior to WW1, and backward to the Fin de Siècle, was a remarkable time. (I’ve touched on this before in particular with Vienna). But Pound could marinate in, as did countless others, the energy and curiosity of this age. WW1 shut it down, though. And Pound was right, the shadow of that first world war would remain indefinitely. Perhaps forever. But my point is more to do with the destruction of modernism. The destruction of most received ideas about art and culture. And also, about, in a sense, about education and writing. Pound had a huge influence on me in my late teens, then again a decade later. And my first attraction was in his ABC of Reading. A book now hugely out of favour, I think. If the Fin de Siècle marked the end of an era and the dawn of another, then that short window before WW1 takes on a special quality of importance. The ABC of Reading was first published in 1934. Michael Dirda in the introduction writes that Pound was in a way anticipating the blog, the internet. And ABC of Reading is really unlike most books of aesthetics. And it occurs to me here that I am certainly more influenced by this book than I had even previously imagined.

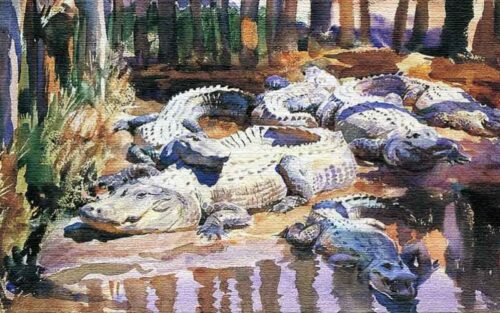

John Singer Sargent

“T. S. Eliot viewed Pound’s criticism as “almost the only contemporary writing on the Art of Poetry that a young poet can study with profit.” As he stressed: “Pound was original in insisting that poetry is an art, an art which demands the most arduous application and study; and in seeing that in our time it had to be a highly conscious art. He also saw that a poet who knows only the poetry of his own language is as poorly equipped as the painter or musician who knows only the painting or the music of his own country.” Certainly Pound took the creation of art, and the writing of poetry in particular, as a serious commitment, requiring study and apprenticeship. { } Like George Orwell in “Politics and the English Language,” Pound repeatedly underscores the importance of honest, efficient language for human communication. “If a nation’s literature declines,” he writes, “the nation atrophies and decays.” No wonder that one of Pound’s favorite Chinese ideograms, “Ching Ming,” is the symbol for precise verbal definition, for calling a thing by its proper name.”

Michael Dirda (Introduction to ABC of Reading)

Today, not only has literacy declined overall, and in media the grammatical mistakes are shockingly common, but it is the ‘arts’ that the decline is most pernicious. Academia does not demand rigour or seriousness. In fact, even at elite Universities, the writing is pretty bad if not atrocious. In institutions of power its much the same; politicians lie, but they lie badly, and media no longer even makes an attempt to be rigorous. Now this is the West, for the age of the Global South is emerging, I think.

Ezra Pound

The regressive side of the Sixties came in the idea of that ribbon for participation. That somehow excellence was authoritarian. That class conflict should be attacked from the creation of false equality. Not economic equality (too UnAmerican) but social equality. But it was always in bad faith. And I have written before on the distrust of teachers. Teacher or mentor became Werner Erhard, not Wittgenstein. The white bougeoisie embraced Asian religion (or practices) also from the wrong end — and accepted the *actual* authoritarian nature of much of Buddhist society, while finding decades of silent meditation (for example) as just too fucking hard. Pound was too hard. I found in theatre (and a noted theatre director said this to me) critics don’t want rigour they want something that at least suggests amateurishness. Fun, amateurs were more fun. Ballanchine was not fun. And this speaks to the ambivalence in white US culture about African independence. (The FLP were not fun, Robben Island was not fun, Nkrumah was not fun). Is it coincidence or happenstance that the IDF makes endless tiktok videos with music and zany dancing, right before slaughtering children and mothers?

“The author hopes to follow the tradition of Gaston Paris and S. Reinach, that is, to produce a text-book that can also be read ‘for pleasure as well as profit’ by those no longer in school; by those who have not been to school; or by those who in their college days suffered those things which most of my own generation suffered.”

Ezra Pound (ABC of Reading)

There is a side bar here that brings Auden back to the discussion. https://www.nybooks.com/online/2019/02/27/auden-on-no-platforming-pound/

Pound, like Auden, was a climate of opinion. Of taste. The spiralling madness that drove Pound has been written about endlessly. And its painful reading. And ended with twelve years in a mental hospital. But it’s also worth noting that Pounds editing of Eliot’s Waste Land took place well into his admiration for Mussolini and fascism. His championing of Joyce, as well. Older friends like Basil Bunting and Williams were deeply saddened by Pound’s politics. He was a miserable non existent father, too, and by the 1930s, the end of the thirties, he was, I think, some form of insane. That era in Paris has become almost a cliche (Hemingway drove Pound’s wife to the hospital to give birth to their child, of which it turned out he was not the biological father) and yet, the massive energy and the cultural imagination, the collective imagination of high modernism is most acutely felt during these years.

Horacio Garcia Rossi

The ABC of Reading occupies a similar cultural space as Peter Brook’s The Empty Space. The first is on writing and poetics and the latter on theatre. Both are full of things I disagree with but both constitute essential reading. For they are bigger than their mistakes. That workd ‘sensibility’ arises here, again. That said, Pound’s Cantos are impossible to really classify as ‘great poetry’. They are something, but I’m not sure, except in places, that they are even readable. But there is genius in the parts that work.

“The old men’s voices, beneath the columns of false marble,

20

The modish and darkish walls,

Discreeter gilding, and the panelled wood

Suggested, for the leasehold is

Touched with an imprecision… about three squares;

The house too thick, the paintings

25

a shade too oiled.

And the great domed head, con gli occhi onesti e tardi

Moves before me, phantom with weighted motion,

Grave incessu, drinking the tone of things,

And the old voice lifts itself

30

weaving an endless sentence.

We also made ghostly visits, and the stair

That knew us, found us again on the turn of it,

Knocking at empty rooms, seeking for buried beauty;

And the sun-tanned, gracious and well-formed fingers

35

Lift no latch of bent bronze, no Empire handle

Twists for the knocker’s fall; no voice to answer.

A strange concierge, in place of the gouty-footed.”

Ezra Pound (Canto VII)

Awoiska van der Molen, photography.

The great domed head is, of course, Henry James. In 1960 Donald Hall edited a collection of poems called The New American Poetry. It was a very successful book, and has had an enduring influence on American poetry. Among the poets were three Black Mountain poets, Charles Olson, Creeley and Denise Levertov, Beats Alan Ginsburg and Gary Snyder, and New York School John Ashbery and Frank O’Hara. Robert Duncan was in there, too, and Jack Spicer. Edward Dorn and John Weiners and Philip Lamantia. I remember pouring through it, everyone did. Only Snyder and Edward Field are still alive. Now, while much of the work of this so called 3rd generation of American poets has not aged well, that is to be expected. Some have aged well. But it raises other issues, now, sixty some years later. And those have to do with things that Donald Hall was aware of. At least I suspect he was. The second generation of poets meant Elizabeth Bishop, Rexroth and James Merrill and maybe Ashbery even — I’m guessing because it seems this is a far from decided category. The first generation though, would be Pound and Stevens and Williams, and running alongside this were the great college professors who happened to be poets; John Crowe Ransom (who was an excellent critic I have to say), and Alan Tate and Richard Wilbur. I’m pretty certain few of them are read nowadays at all. These were the men Robert Bly began protesting against with his magazine The Fifties (later the Sixties etc). And by this point, by 1960 when Allen’s anthology came out, the most important writing has happening in other languages (Spanish for certain, but German and Swedish and Russian). And this was Bly’s importance (or one part of his importance). His translations of Neruda and Vallejo and Blas de Otero and Hernandez profoundly changed poetry in America, whether America knew it or not.

Here is the second stanza of Robert Lowell’s The Quaker Graveyard in Nantucket

“Whenever winds are moving and their breath

Heaves at the roped-in bulwarks of this pier,

The terns and sea-gulls tremble at your death

In these home waters. Sailor, can you hear

The Pequod’s sea wings, beating landward, fall

Headlong and break on our Atlantic wall

Off ’Sconset, where the yawing S-boats splash

The bellbuoy, with ballooning spinnakers,

As the entangled, screeching mainsheet clears

The blocks: off Madaket, where lubbers lash

The heavy surf and throw their long lead squids

For blue-fish? Sea-gulls blink their heavy lids

Seaward. The winds’ wings beat upon the stones,

Cousin, and scream for you and the claws rush

At the sea’s throat and wring it in the slush

Of this old Quaker graveyard where the bones

Cry out in the long night for the hurt beast

Bobbing by Ahab’s whaleboats in the East.”

A poem dedicated to a cousin who died at sea during WW2. This stanza evokes Melville and the history of Nantucket. Of American history. Where is this sense of history and mortality in poets today?

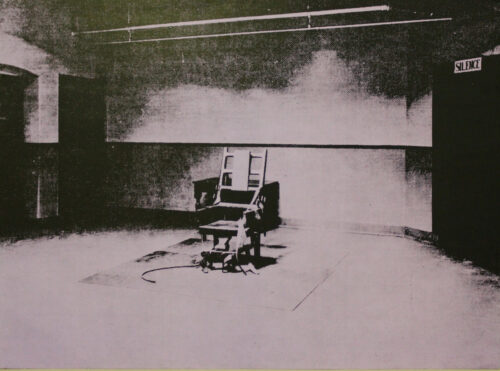

Andy Warhol

Read those poets named by the Harvard Crimson. Here is a poem by Mark Doty, who has a huge rep and is a name I have heard for twenty years now as an important voice.

http://famouspoetsandpoems.com/poets/mark_doty/poems/14741

Its not terrible, but its very close. No, on second read it is terrible. This (from Doty’s poem):

“Suppose we could iridesce,

like these, and lose ourselves

entirely in the universe

of shimmer–would you want

to be yourself only,

unduplicatable, doomed

to be lost? They’d prefer,

plainly, to be flashing participants,

multitudinous. Even on ice…”

Firstly, its imprecise — *would you want to be yourself* is the sound of Oprah conversations, and its narcissistic finally. There is no weight. What Bly called the cold basement stone of sound. It’s fluttery and trivial. Borderline cute.

Here is Charles Olson, the opening stanza of To Himself (and I literally picked this at random)…

“I have had to learn the simplest things

last. Which made for difficulties.

Even at sea I was slow, to get the hand out, or to cross

a wet deck.

The sea was not, finally, my trade.

But even my trade, at it, I stood estranged

from that which was most familiar. Was delayed,

and not content with the man’s argument

that such postponement

is now the nature of

obedience,

that we are all late

in a slow time,

that we grow up many

And the single

is not easily

known”

Carl Andre (1969)

Roethke’s final two stanzas of In a Dark Time

A steady storm of correspondences!

A night flowing with birds, a ragged moon,

And in broad day the midnight come again!

A man goes far to find out what he is—

Death of the self in a long, tearless night,

All natural shapes blazing unnatural light.

Dark, dark my light, and darker my desire.

My soul, like some heat-maddened summer fly,

Keeps buzzing at the sill. Which I is I?

A fallen man, I climb out of my fear.

The mind enters itself, and God the mind,

And one is One, free in the tearing wind.

The Olson and Roethke are random picks for the most part.

Here is one of the great American poems. James Wright.

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/poems/27765/at-the-executed-murderers-grave

It is a bit too long to put here, but read it. Wright is probably my single favorite poet. He and Vallejo. And Bly. But Wright was special. So, if one compares Wright and Olson and Roethke…with Doty or pick any contemporary. What is different? For there is a difference. Language feels flabby now. There is no historical echo, nothing uncanny or haunting. Here is a small poem by William Carlos Williams..

“Of death

the barber

the barber

talked to me

cutting my

life with

sleep to trim

my hair —

It’s just

a moment

he said, we die

every night —

And of

the newest

ways to grow

hair on

bald death –

I told him

of the quartz

lamp

and of old men

with third

sets of teeth

to the cue

of an old man

who said

at the door —

Sunshine today!

for which

death shaves

him twice

a week”

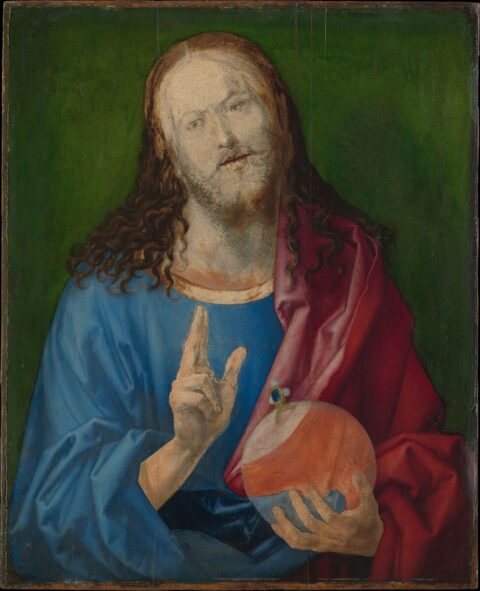

Albrecht Dürer (Salvator Mundi, 1505. Never completed)

First, Williams and Olson and Rothke and Wright are adults. I cannot help but feel the childishness in today’s poets. There are a host of influences, even if we leave out advanced capitalism, and media and digital tech. And one stream of influence is entertainment. Not just the valorizing of this idea but the fact that *entertainment* included under its umbrella, as it were, much of Camp , which then became kitsch. It infected all cultural expression. One branch of this infection took the form of silly effite queer trivialness, and another took the liberal culture of assumption. Liberal assumption of knowing what is best for you. Its for your own good. The electric chair, I know is harsh, and I’m sorry, but its for your own good. Both contribute to this infantilism in the West. It is also the fatherless society. I wrote of this last time and we talked of it on the podcast; but the incomplete Oedipal, the interruption of psychic formation, leaves the child to transfer the Father imago. Or, more complexly and troubling is the invention of artificial completion.

There can be no adult poetry when there are no adults. Looking back I always wondered at the seemingly overheated adoration of Rimbaud. Part of it was his gay romance (sic) with Verlaine. But more it was young poetry, it was in many sense immature. Now there have been very adult poems written by young men and women. But Rimbaud was not one. It was also the front edges of what is now a new narcissism. Meaning not of antiquity. This is not to say I think Rimbaud lacks importance. I think he has genuine importance, though Comte de Lautréamont has more.

“Since patients with feelings of estrangement are very much preoccupied with their own states, this would indicate a concentration of libido on the patient’s ego, and thus an “increase in narcissism.” { } It may seem amazing to speak of “objectless narcissism,”since it has become customary to consider and designate object libido and narcissism as absolute antitheses. But they are not antithetic conceptually, because certain types of narcissism, disregarding the ego feeling, always have the ego or parts of it as their object. In actual antithesis to each other are “object cathexis” and “ego cathexis”; the first term indicates that the object, and the second that the ego, is that which is cathected by the libido, that which is experienced with pleasurable desire.{ } It is Freud’s basic assumption that “. . . it is impossible to suppose that a unity comparable to the ego can exist in the individual from the very start; the ego has to develop . . .” This assumption derives from the non-unitary nature of the”id.” I hold, however, that an ego feeling is present from the very beginning, earlier than any other content of consciousness.This hypothesis corresponds to that of many philosophers an psychologists and to the view shared by many biologists that agerm of consciousness—I would like to call it a rudimentary ego feeling—pertains to every protoplasmic organism, even the lowest one, and thus to every living being.”

Paul Federn (Ego Psychology & Psychosis)

Federn wrote this in 1952. I bring this up here because Federn was the great thinker on narcissism. Winnicott was influenced by him and Anzieu. But the point is that perhaps without knowing it, Federn’s ideas on narcissism anticipate the post modern condition of screen addiction — he saw the blank generation coming.

Adam Jeppesen

“If a person does not in fact go about his business with the mastery and efficiency of a leopard, it is because he is far more conflicted about the expression of his instincts; his ego and id, unlike the leopard’s, are divided against each other, and he even has a superego to further complicate things. This is the price, Freud will argue in Civilization and Its Discontents (1930), of living in a society.”

Samuel Sellinger (Ego-Feeling and Ego-Boundaries: An Examination of the Work and Legacy of Paul Federn )

One would add, living in a capitalist society. A digitally mediated society. The narcissist of Federn’s thinking only knows who he is because he feels he knows who he is. And subsequent riffs on Federn suggest the narcissistic patient can fake this ego feeling. Sellinger makes two points here…“. When he delivered his lecture “Narcissism in the Structure of the Ego” (1928, p.38), Federn made the argument that the maintenance of the ego requires a steady infusion of libido.”

And point two: even the clearest knowledge of one’s own ego is experienced as insufficient. I would argue today this pathological condition of not believing in one’s own self could almost be described as common.

Objectless narcissism is getting close to ‘the dream dreaming the dreamer’.

“In beginning his discussion on dreams, Federn notes a curious observation: patients who report feelings of derealization invariably described the experience as like a dream.”

Samuel Sellinger (Ibid)

What makes us think or believe something is real? The answer is found in art, in all creativity.

I am reminded of Auden’s essay on Kafka: “If there ever was a man of whom it could be said that he “hungered and thirsted after righteousness,” it was Kafka. Perhaps he came to regard what he had “written as a personal device he had employed in his

search for God. “Writing,” he once wrote, “is a form of prayer,” and no person whose prayers are genuine, desires them to be overheard by a third party..”

W.H. Auden (The I Without a Self; The Dyers Hand)

Juan Jose Hoyos Quiles

“We understand now why “primary narcissism” at its peak, with its strong id derived drive and pleasure energy, very much overshadows the simple ego feeling. One’s own ego feeling assuch becomes perceptible only upon the repression of the autoerotic experiences and experience traces, with the predominance of the interest for objects. But even for the adult ego feeling is so much obscured by autoerotic, and even more by object libidinal contents of consciousness, that only in the case of variations and disturbances could it attract the attention of self- observing persons and of the researcher.”

Paul Federn (Ibid)

How easy the child of a missing father transfers to commodities or cults the desire normally lavished upon his own ideal. Treat your friends like appliances and your appliances like friends.

“And what makes us feel that an experience is vivid? Federn’s answer is that it is the investment of energy into a sensitivity at the borders of the ego, which he terms egoboundaries. In each case– derealization, and dreaming—the ego-boundaries are implicated. Something is felt to be real when it is perceived to be outside of the ego-boundary; as the area of ego-feeling retracts in sleep, mental experiences are felt to be real because they are experienced from outside. But in moments of derealization, the investment ego-feeling along the ego-boundaries is weakened, and the sensations are experienced as lifeless or unreal. “

Samuel Sellinger (Ibid)

James Wright

When dreaming these psychic borders retract. In acts of creativity, they retract. In cases of pathological narcissism, malignant narcissism, the recognition of ‘realness’ is distrusted. Only the subjects own internal world, which has shrunk, is to be trusted. The walls close in. The narcissist currency is paranoia beyond a certain point of intensification. Fascism, the adoration of the ‘strong’ leader, orator, ‘new’ man — and fascist leaders are men. Women can be fascists, Thatcher was essentially a fascist, but Thatcher could not be Mussolini. Fascist leaders almost must be paranoid narcissists.

The confusion today, in the U.S. public regards left and right, fascism and communism, speaks to this infantilism. Electoral politics are much like early grade school readers now (See Kamala run, run Kamala run. Etc.). Poets verse is thin and neurasthenic in a sense. The world is dominated now by billionaire sociopaths (someone really has to stop Bill Gates. Enough) and the resurfacing of a fascist sensibility, itself more adolescent than infantile.

Perhaps John Donne’s most famous sermon, or one of them, is Divine Meditation 17. https://www.luminarium.org/sevenlit/donne/meditation17.php#:~:text=No%20man%20is%20an%20island%2C%20entire%20of%20itself%3B%20every%20man,am%20involved%20in%20mankind%2C%20and

Written in 1624 while Donne was deathly ill with Typhus. (He did recover). He completed twenty three sermons collected under the title Devotions upon Emergent Occasions. It is among the greatest writing in English. It rivals Shakespeare. Number 17 begins with a Latin epigraph :

NUNC LENTO SONITU DICUNT, MORIERIS.

Now this bell tolling softly for another,

says to me, Thou must die.

Mirosław Bałka

Read it and consider the mind that could create such a work. Strictly speaking its not a poem. But no matter. The density of the language and the depth and sound, the cadence that carries the emotion, is remarkable. His poem Easter Sunday 1613 is equally remarkable (and you could pick any part of it…)

Could I behold those hands which span the Poles,

And tune all spheares at once peirc’d with those holes?

Could I behold that endlesse height which is

Zenith to us, and our Antipodes,

Humbled below us? or that blood which is

The seat of all our Soules, if not of his,

Made durt of dust, or that flesh which was worne

By God, for his apparell, rag’d, and torne?

John Donne (Good Friday, 1613. Riding Westward)

There are, I am sure, some poets out there. I know some personally who I think are legitimately good. But the overall voice of the 21st century is stunningly childish and puerile. People no longer meditate on language. On sound. Children are warehoused electronically guarded by screens they seemingly cannot leave. The public does want the weight of being adult. Adults are just buzz kills anyway. During the genocide in Gaza (ongoing) I thought of Donne and sermon 17…” any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind, and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.”

To donate to this blog use the paypal button at the top of page. Donations also help keep the Aesthetic Resistance podcasts going.

https://aestheticresistance.substack.com/

My computer’s toast so this is from my phone. Apologies. So much to say about the state of poetry, but I’ll simply provide a link to Charles Wright reading “March Journal” and hope people keep searching out good poems/poets as we await the Rapture.

https://voca.arizona.edu/track/id/62644

thanks. Still alive, at 89. Five years younger than Snyder.

An insightful critique of contemporary woke culture, academics and poetry. I wonder where this ….”read your close contemporaries first. Then go back and start at the start” leaves those coming of age today, for whom the chosen Harvard Crimson poets are vanguard.

Hoping you might include a bit of this discussion in your next online teaching series.

good point about contemporaries. I think that means, in this case, mid century poets….start there…..