Agnes Martin

“Why is almost every robust healthy boy with a robust healthy soul in him, at some time or other crazy to go to sea? Why upon your first voyage as a passenger, did you yourself feel such a mystical vibration, when first told that you and your ship were now out of sight of land?”

Herman Melville (Moby Dick)

“It is possible that here we are facing a fourth ‘narcissistic wound’ namely that even the intelligence of which we are so proud, though analysts, is not our property but must be replaced or regenerated through the rhythmic outpouring of the ego into the universe, which alone is all knowing and therefore intelligent. But more of this another time.”

Sandor Ferenczi (Diaries)

“The newborn poetic image—a simple image!—thus becomes quite simply an absolute origin, an origin of consciousness. In times of great discoveries, a poetic image can be the seed of a world, the seed of a universe imagined out of a poet’s reverie.”

Gaston Bachelard (The Poetics of Reverie)

“As we will see, the idea that technology is neutral is itself not neutral— it directly serves the interests of the people who benefit from our inability to see where the juggernaut is headed.”

Jerry Mander (Absence of the Sacred)

People have argued about social formations for as long as people have existed. Some see small groups (under one hundred) that one can know on a face to face basis as ideal. This is the belief that humans are somehow tribal by nature. Others see vastly more complex social groupings as more preferable. But both will debate the cut off points for ‘too many’ or ‘too few’. Robin Dunbar, the British anthropologist sets the number at one hundred and fifty.

“According to Dunbar and many researchers he influenced, this rule of 150 remains true for early hunter-gatherer societies as well as a surprising array of modern groupings: offices, communes, factories, residential campsites, military organisations, 11th Century English villages, even Christmas card lists. Exceed 150, and a network is unlikely to last long or cohere well. (One implication for the era of urbanisation may be that, to avoid alienation or tensions, city residents should find quasi-villages within their cities.)”

BBC (Dunbar’s Number, 2019 Psychology)

Now Dunbar was riffing off some golden equation having to do with the brain, or the neocortex anyway, and the size of groups one lives in, and how such groups sustain themselves. And also with cognition and cohesive relations. Dunbar was basing most of this on primate groups. The early human foragers or bands were usually informal groups of families, rarely exceeding a few dozen. These were called acephalous groups, or headless groups. A tribe is the next step up in complexity. Both foragers and tribal pastoralist groups are based, usually anyway, on kinship. Now there are a myriad of mitigating factors to any such idea of fixed size. And such discussions quickly beg the question of what one means by ‘good’? If 150 is ideal, the question is ideal for what ?

Dance, dairy farm between Meldal and Rindal, Norway. Apprx 1918.

If smaller bands or tribes are designated ‘better’, one assumes better means stable, less violent, and most of all less stressful. But I am not at all sure anyone can formulate an ideal group size for anything really. What does *desire* mean in foraging groups? How does the unconscious of early foraging man develop? Now I am probably willing to admit smaller is better in the sense of emotional security and the reinforcements of familiarity. But it is very hard to adduce from the last of the tribes or bands, most of whom disappeared in the 19th century (there are a few rare outliers still but even the people on those Indian owned islands are now feeling the contact of the 21st century) answers to any of this. But what interests me is how one evaluates the idea of society, of why one lives in a society, of what one would change in that society. These questions are arising now because of the dissolution of the old. A system in place for hundreds of years is dying. Certainly western society is dying. The current U.S. elections suggest this is exactly what Gramsci described, the *fenomeni morbosi* (or symptoms, depending on how you translate the Italian) —

Gilbert Archar wrote “However, the central idea in Gramsci’s famous sentence belongs to the appraisal of any transitional phase during which an old order is already dying, but a radically different new one is not yet able to be born – an appraisal that was key to Marx’s analysis of Bonapartism. Gramsci and his fellow Italian Marxists could not fail to find in it a clue to their own analysis of fascism, which they saw indeed as a degenerate form of Bonapartism.”

(Morbid Symptoms: What Did Gramsci Really Mean? Journal for the Studies of Power)

Now, there are several sort of templates, anthropologically speaking, on the evolution of human society. Rousseau’s (Discourse on the Origin and the Foundation of Inequality Among Mankind), written in 1754, is perhaps the most well known and most influential.

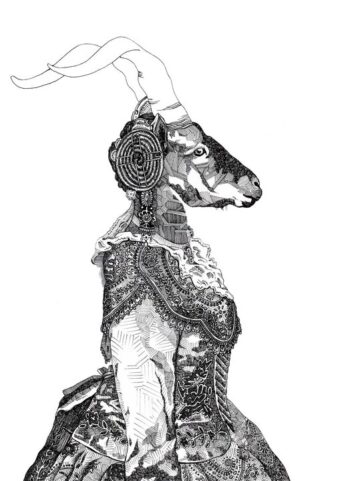

Stephane Mandelbaum

“Once upon a time, the story goes, we were hunter-gatherers, living in a prolonged state of childlike innocence, in tiny bands. These bands were egalitarian; they could be for the very reason that they were so small. It was only after the ‘Agricultural Revolution’, and then still more the rise of cities, that this happy condition came to an end, ushering in ‘civilization’ and ‘the state’ – which also meant the appearance of written literature, science and philosophy, but at the same time, almost everything bad in human life: patriarchy, standing armies, mass executions and annoying bureaucrats demanding that we spend much of our lives filling in forms.”

David Graeber (The Dawn of Everything)

A bit later Graeber touches on the issue that interests me, and oddly, an issue that seems not to be foregrounded very often in anthropological studies.

“The ultimate question of human history, as we’ll see, is not our equal access to material resources (land, calories, means of production), much though these things are obviously important, but our equal capacity to contribute to decisions about how to live together. Of course, to exercise that capacity implies that there should be something meaningful to decide in the first place.”

David Graeber (Ibid)

Those small groups of hunter/gatherers, twenty thousand years ago, had no written language and built (so it is believed) almost nothing of a permanent nature. And they did this, this ‘not much’, for thousands of years. In one cave in Spain there are paintings covering earlier paintings. And the earliest are several thousand years earlier than the later. What was everyone doing? For modern humanity changes occur as such an accelerated pace that these kinds of perspective on time are very hard to grasp. But these early communities were busy surviving, mostly. Abundance later brought reflection and more time to ponder this world around them. These were, as John Berger said, the people of arrival. But there was no Shakespeare, no Bach, no electricity or temples or smart phones. And no sense of identity in the form we take for granted. It is postulated that humans began to use names, in a formal sense, about five thousand years ago. But this is idle speculation, really. First written name was Sumarian and was officially 5000 years ago. Unless that name was a title or something else entirely. Directions to the restroom or exit.

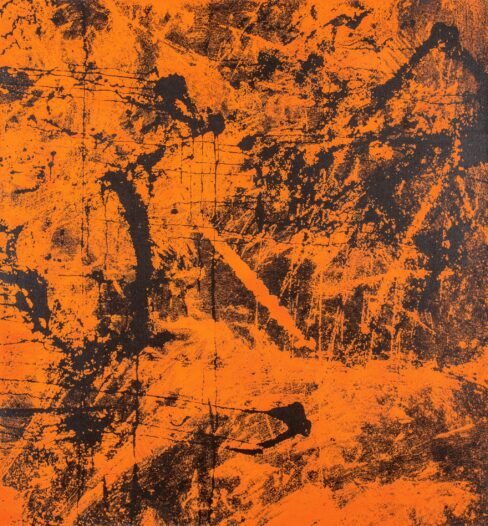

Paul Jenkins

The question, though, is what ‘is’ a healthy or happy society? And Jared Diamond noted (quoted by Graeber) “Alas for all of you readers who are anarchists and dream of living without any state government, those are the reasons why your dream is unrealistic: you’ll have to find some tiny band or tribe willing to accept you, where no one is a stranger, and where kings, presidents, and bureaucrats are unnecessary.” Now, if agriculture was the motive force for a new level of abundance in early communities, there are questions regarding exactly how this agriculture developed. I mean if it was as gradual as one imagines, and that over a couple centuries, at the least, the idea of keeping seeds and caring for young plants etc developed, then that surplus would be very gradual, as well. How did this drive privilege, exactly? There are countless scenarios I can imagine, none backed by anything remotely like scientific evidence. But this is history. There will never be scientific evidence for slow gradual change in human groups. It is also impossible to ascertain changes in diet and the effects that may have had (although some evidence does exist, like lack of any cavities found in the skeletal teeth of early humans). Surplus interacted with the development of writing and naming. It overlapped with a developing knowledge about health and predictions regarding weather and seasons. And how did such agriculture lead to more travel, more migration? I think this is slightly counter intuitive. And this is where tribal chauvinism surfaces. I suspect small tribal groups were no less rent by jealousy and rage than large societies.

Infants recognize the sound of their mother’s voice from inside the womb (and father’s). There are instincts for family. And one does wonder at the stunning wrongheadedness of much science today in ignoring this. Artificial wombs are not just stupid, but they will not, finally, work. They will produce sick and psychically stunted children. Children who are maladaptive and depressive. Auto-orphaned, in a sense. Neanderthal children knew their mother’s voices, too. All primates have sophisticated family structures and yet no language. This is the issue that nags at me about surrogacy in general, for parents. But is interesting to consider why people continued to assemble and live in ever larger groups.

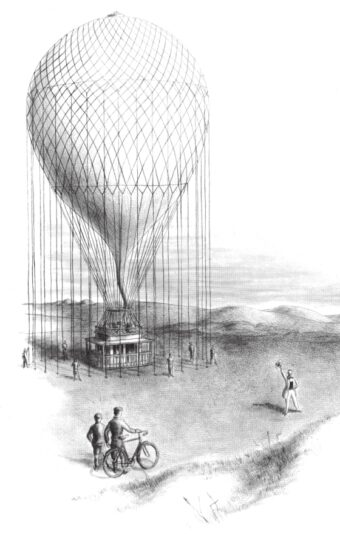

William Pene du Bois (illustration for The 21 Balloons, 1947)

“The founding text of twentieth-century ethnography, Bronisław Malinowski’s 1922 Argonauts of the Western Pacific, describes how in the ‘kula chain’ of the Massim Islands off Papua New Guinea, men would undertake daring expeditions across dangerous seas in outrigger canoes, just in order to exchange precious heirloom arm-shells and necklaces for each other (each of the most important ones has its own name, and history of former owners) – only to hold it briefly, then pass it on again to a different expedition from another island. Heirloom treasures circle the island chain eternally, crossing hundreds of miles of ocean, arm-shells and necklaces in opposite directions. To an outsider, it seems senseless. To the men of the Massim it was the ultimate adventure, and nothing could be more important than to spread one’s name, in this fashion, to places one had never seen.”

David Graeber (Ibid)

This seems profoundly important. But it is also strangely confusing, I think. Foragers and tribal groups stay at the same level for a thousand years. Yet sometimes they don’t. And we could speculate about the reasons for that, but I think the reason is outside and beyond the material factors in most cases. Why was spreading your name important (to the Massim Islanders)? There are more than a few related examples of this. Why go to sea at all? Why did young men go to sea ever, anyplace?

“…we should like to emphasize once and for all that the idea of seeking a kind of historical parallel to the individual experience of the catastrophe of birth and its repetition in the act of coitus was not imposed upon us by any of the facts of natural science, but only by psychoanalytic experience, in particular by observations in the sphere of symbolism. For if through observations a hundred times repeated one becomes confirmed in the preconception that in symbolic or indirect forms of expression on the part of the psyche or the body, there are preserved whole portions of buried and otherwise inaccessible history-much in the manner of hieroglyphic inscriptions from out of the prehistoric past-and if, an equal number of times, the deciphering of these symbols and characters in the history of the individual proves valid, it is perhaps understandable, and at the same time its own excuse, that one should also venture to make use of this method of cipher-reading to decode the vast secrets of the developmental history of the species. As our teacher Freud has often repeated in connection with similar attempts, it is certainly no disgrace if one goes astray in making such flights into the unknown. At the worst, one will have set up a warning signpost on the road one has traversed which will save others from similarly going wrong. “

Sandor Ferenczi (Thalassa)

Frank Stella

This is the opening paragraph of Ferenczi’s book, published in 1924. He adds that the symbol of the fish seems to occur repeatedly in analysis. He adds…“the fantastic idea leapt to mind as to whether, over and above the purely external similarity between the situation of the penis in the vagina, the fetus in the uterus, and the fish in the water, there might not also be expressed in this symbolism a bit of phylogenetic recognition of our descent from aquatic vertebrates.”

This is rather remarkable. But it raises questions about the Rousseauian template for civilizational evolution. The idea of a recapitulation of the history of the species is today regarded as mere superstition, if even that. And yet, the unconscious does not lie. And those early pre agricultural communities at some point did (in various forms) ‘go to sea’.

I have said often that all stories are about homesickness (and exile and crime). Our own story is also such. The urge or drive to venture forth across an unknown sea is the story of both our own birth and the birth of our species. It is also a search for a way home.

Graeber adds a note on vision quests, not uncommon in North American indigenous communities and tribes: “among Iroquoian-speaking peoples in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries it was considered extremely important literally to realize one’s dreams. Many European observers marvelled at how Indians would be willing to travel for days to bring back some object, trophy, crystal or even an animal like a dog that they had dreamed of acquiring.”

(Ibid)

Isaac van Duynen (1650s, detail)

“Thomas Ogden describes the conscious reveries that characterise one of the states of the analyst during session. He recognises their role in the elucidation of the unconscious experience of the patient. As he tells us (Reverie & Metaphor) ‘Reverie is a principal form of re-presentation of the unconscious (largely intersubjective) experience of analyst and analysand. The analytic use of reverie is the process by which unconscious experience is made into verbally symbolic metaphors that re-present unconscious aspects of ourselves to ourselves.”

Raluca Soreanu (Ferenczi’s Times)

Now, I asked earlier about *desire*. And I think this is, the more I reflect on it, of huge importance in trying to understand the current maladies of the advanced West, and the path that brought us here. And this journey that is *Desire* is foundational, and also complex. Because oddly enough all the various theories of man’s origins seem to neglect desire. Much as they neglect the Ferenczian notion of recapitulation, or Bachelard’s notion of ‘reverie’. Normalcy cannot be posited, it seems, without narrowly defining the human. In other words the calculus of human societal development is one that must remove the ‘stuff’ that gets in the way of a clean explanation. And part of the problem is found in the idea of time. Christian time. A march toward redemption. That at the end of all this is some sort of conclusion, a plot reveal, a deus ex machina, something. And for that idea, which is really ‘progress’ (I suppose there are negative versions of time, some vision of human regression, but its a very minor belief if it exists). And yet, even Einstein understood beginnings and ends were problematic in terms of theory. There cannot be a beginning for something had to exist before that beginning. And often, I think, cosmological thinking runs into contradictions if it insists on this Christian time. A linear one directional move toward perfection (or redemption or something). So, if one tries to grasp the evolution of consciousness, one is forced to posit a moment, or series of moments when that stationary sea slug began to exhibit something like sentience. When do we consider jellyfish sentient? Or plankton. Or shrimp.

The people of arrival. And we, today, are the people of departure. I sense that these themes are arising because humanity collectively recognizes its imminent departure.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, photography (Tasmin Sea)

“Freud starts from a newly observed kind of repetition – or a repetition he is now able to look at from a new perspective – which brings him to the hypothesis that there is something akin to a death drive operating in the psyche. The repetition he speaks of is not directly in service to the pleasure principle. He discusses the repetition in traumatic dreams; and the repetition in children’s games (the famous “Fort/Da” game). In both these examples, the dreamer or the child playing cannot derive pleasure from their repeated act. This means that there is another force organising these acts (or compulsions to repeat): Freud will give this force the name of “death drive”.”

Raluca Soreanu (Something was Lost in Freud’s Beyond the Pleasure Principle)

As humanity is recognizing (or some of humanity. Or maybe all of it but there is much denial in places) the need, the imperative, for change. There is an experience of feeling lost. (or fenomini morbosa, too). And here there are multiple intersections. There are massive nations, several with over a billion citizens, and the leaders of these massive states are crippled with their role, their job, their position. They cannot actually make decisions any longer. The system has frozen. A many tiered vapour lock. They speak but no sound comes out. Joe Biden is the perfect PERFECT symbol/metaphor for collective departure, for a sclerotic and aged system for control. Miroslaw Balka’s installation piece (Tate, London) a few years back, ‘Unilever’ was a prescient conjuring of this desire and fear of departure. Looked at from this perspective a number or artists come to mind; Luc Tuyman’s portraits have a sense of both apparition and toxicity. A memory of having ‘gone to sea’. Hiroshi Sugimoto’s ocean photographs certainly rather literally evoke this, and a several other things besides.

“…in a multiplicity of dreams we are forced to interpret the child as a symbol of the penis, the penis signification of the fish on the one hand, and on the other the fish signification of the penis, become more self-evident-in other words, the penis in coitus enacts not only the natal and antenatal mode of exist ence of the human species, but likewise the struggles of that primal creature among its ancestors which suffered the great catastrophe of the drying up of the sea. “

Sandor Ferenczi (Ibid)

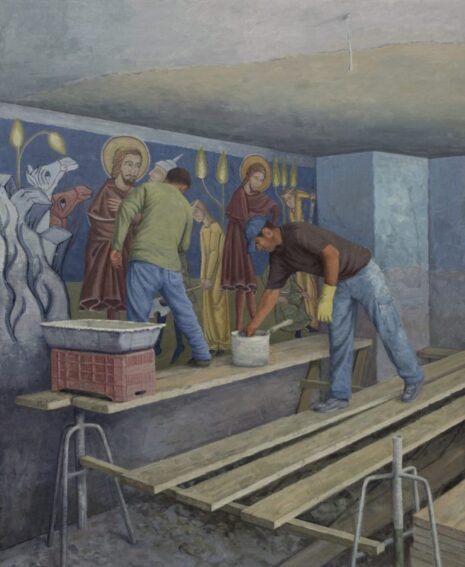

Serban Savu

The people of an ending. The world is no longer an open unknown and mostly lonely wilderness. Everywhere are testaments to pointlessness, to excess, to arrogance and hubris. We are the last party guests to leave. Hungover, stupified, shell shocked and we stumble, both literally and intellectually, out into the glaring sun, shielding our eyes, thirsty and surprisingly alone.

“ Only someone who prevents us from satisfying a desire that he himself has inspired in us is truly an object of hatred. The mimetic nature of jealousy and envy is also underscored: Jealousy and envy, like hatred, are scarcely more than traditional names given to internal mediation…Jealousy and envy imply a triple presence: object, subject, and a third person toward whom the jealousy or envy is directed. These two ‘vices’ are therefore triangular.”

Jean-Michel Oughourlian (The Mimetic Brain)

Somewhere at this point you can google the story of Phineas Gage. But back to the mimetic again, and the nature of community. Now :

“The “Freudian” father—that is to say the father at the end of the nineteenth century—represents taboo, and the identification with the latter, that is to say the imitative integration of that taboo, is baptized “superego.” This prohibition is loving and benevolent, and not categorical: the father establishes laws—’We eat when we’re at the table, you can play later,’ ‘You can have a bicycle when you’re older,’ ‘We’ll go to the countryside tomorrow if you behave.’ In other words, this superego reinforces desire through taboo in that it teaches desire to delay gratifi cation and thus to maintain itself as it awaits its realization’ { } In the formation of the self, Freud emphasizes the central and fundamental role of the child’s relationship with the mother. If we wanted to express this in our vocabulary, we would say that the interdividual rapport with the mother fashions and nourishes the self-of-desire, which is thus at first the self-of-the-mother’s-desire. Th is desire must therefore be the strongest, the most positive, and the most ambitious desire possible for the child. But this desire would be vain if it was not accompanied by the mother’s love, which, in our vocabulary, constitutes the affective reserves of the second brain.”

Jean-Michel Oughourlian (ibid)

Sandra Gamarra

The second part of the Melville quote at the top of this post goes like this … ” And still deeper the meaning of that story of Narcissus, who because he could not grasp the tormenting, mild image he saw in the fountain, plunged into it and was drowned. But that same image, we ourselves see in all rivers and oceans. It is the image of the ungraspable phantom of life; and this is the key to it all.”

Desire then exists in all groups, if Girard is right. We desire the desire of others — but from whence comes their desire? The Girardian blueprint has desire using either model, rival, or obstacle. And these are on a gradient. If the subject uses model, free of rivalry, then we have friendship. A model is found in the teacher, as well. But the rival is the dark side of mimetic relationships. And rivalry is baked into capitalism at its core. The rival cannot be tolerated for it is a threat to the object one desires, and this in turn can be seen to evolve into obstacle. The other is then an obstacle to my getting what I desire. What is interesting here is that under our current system one’s desire is coloured by various fears; that of indigence, or losing what one already worked for, and this in turn overlaps with insecurity about what one is capable of keeping. My wife will leave me, a competing company will steal my customers, etc. If one imagines the foraging band of early humans, desire is still mimetic but it is also based on a far more immediate relationship with the objects of desire. Today technology has furthered distance from what we want. Our desire is mediated. Or more mediated anyway. Remote desire.

“All of humanity begins to resemble the astronaut in space, spinning in his separate metal containment, millions of miles from the organic roots of our existence. We depend on nourishment that arrives from somewhere far away on ships or planes. We are disconnected from the sources of information we need, now brought to us only through processed images from distant places. We have no direct means of knowing right from wrong, or how to control our experience.”

Jerry Mander (The Capitalism Papers)

So in one sense the 150 number would mean a more direct contact with our own desire. But what of that urge to go to sea?

Jonathan Wateridge

The remote desire of today, then, results in a diluted sense of morality and that generalized autism that Debord identified fifty years ago. The current electoral circus seems to symbolize the fragmented and interrupted quality of daily life in the West. The urge to go to sea has disappeared. The urge to text, perhaps, replacing it. The urge to tweet. But screen life does not take us home.

But if those hunter gatherer groups lived in a face to face world, almost exclusively, then increasingly the world of mass nation states is anonymous. Even face to face encounters are not face to face. They are face by face, but not directed. Anonymity is now the currency of urban life. One can still keep one’s rolodex at 150, but I don’t think that helps. Still, what is being suggested as positive about small groups? Whenever I hear this, I feel that health food store vibe I remember from decades past. Small is better was a *green* mantra and perhaps, maybe, it made some sense in terms of certain kinds of consumption. But scale was never the problem. The problem was moral, I think. Capitalism is amoral. At times immoral. The calculus of desire is such that contemporary life finds it difficult to desire the other as a model. I have noticed a gradual but inexorable decline in the role of teacher. The subject no longer desires the teacher. The teacher is misrecognized. Teacher is possessed (per Girard and Oughourlian). The teacher is nearly always resented. If this bleeds into rival, though more often it is more paranoid than rival. But as rival the teacher is then an object to which we express vengeance. And this is where the roles of teacher and student have become vigilante and pervert. The sexual hysteria of ‘recovered memories’ was a perfect example. The child predator template becomes, even when true, a useful allegory. Men who can teach with patience, but more, with presence, with gravitas are increasingly rare. The interrupted Oedipal drama is involved in this. Women find it hard to form those cooperative guilds from the middle ages, or from Neanderthal bands. They have been indoctrinated as men. Hollywood action hero females are really males, and one wonders how the trans movement is fed by this confusion. And sacrifical victims abound (P Diddy is about to take the fall for collective sins. )

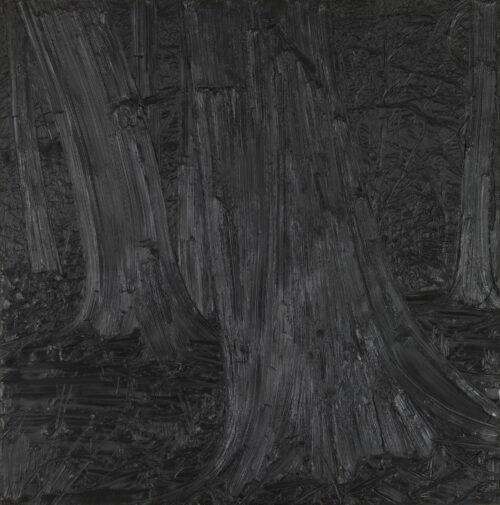

Rudolf Stingel

“The Freudian father represented throughout the duration of life by the superego was a categorical and insurmountable obstacle. Now this kind of father has disappeared, and with him the superego, it seems, such that our society is obliged to multiply the number of laws and rules in an attempt to predict all possible infractions in all areas. In the ambient cacophony, justice itself continuously becomes subject to negotiations, challenges, and legal nitpicking, it being understood by the lawyers on both sides that every argument can be countered by another argument. Justice is dissolved into litigiousness when it proves incapable of replacing the father’s categorical imperative and unquestioned authority.”

Jean-Michel Oughourlian (Ibid)

The hunter gatherer tribes or bands of early man, and more, the Neanderthal bands before them, probably never exceeded a hundred. Perhaps that grew in places to two hundred. But DNA suggests early Neanderthals had pretty small breeding populations. And inbreeding was normal. Whether they were patrilocal or matrilocal is unclear. They may have been both. Gender difference in size has gradually lessened over time, but for Neanderthals the size of both genders was relatively the same. Now the question nobody can answer is whether these Neanderthal tribes or bands were kinship aware or not. Also, the last Neanderthals disappeared through inbreeding with homosapiens. This was about 40,000 years ago. All things considered that’s actually not very long ago. Now I mention all this because it is still a distant and unknown world. Female Neanderthals, it can be determined, carried their babies around with them. It is likely, so we are told, that females worked together cooperatively while males hunted further from the location of the group. The primary task for Neanderthals was hide work (their teeth seem to indicate they were used extensively for pulling and holding etc). But creating hides for clothing was the basic occupation on which most of their days were spent. The total population of Upper Paleolithic Europe thirty thousand years ago was around 5000. It might have been higher. Nobody knows. But this increased 15 thousand years ago, to 30,000.- But there are a lot of debates around all of these figures. The answer is nobody knows. But populations increased. It is also fascinating to note that there are several lineages of Cro-Magnon related people (sic) that died out and did not contribute DNA to our ancestry. Who were they? Why did they not prosper? Also, nearly all Cro-Magnons were dark skinned. (blue eyes did not occur until ten thousand years ago, roughly). And all blue eyed people, including two of my sons, have a single common ancestor. Someone born with a mutation that turned off melanin in the iris. One wonders who that child was.

Also interesting is the evolution of hunting. For this suggests an architecture for the growth of group size. Cro-Magnon man, in western Europe, seemingly had learned to drive wholé herds of bison and deer up to a cliff face or into a mountain wall of some sort, and had learned the seasons to do this depending on the habits of the herds. The mass killing events were held based on knowledge of migration patterns for animals like reindeer or red deer or moose. This became an event for all groups or tribes in that area. It meant party time essentially and for some young women, they left with new tribes and for others it was the young men who left.

Emmanuel Lafont

The late Pleistocene saw an extinction event for mega fauna. Meaning massive die off of much of what constituted the diet of Cro Magnons. This occured over a pretty long period (50,000 thousand years ago in what is now Australia and 15,000 years ago in what is now the Caribbean. In Australia something like 60% of herds died off, but other places it was more like 10%). But the point was the socializing that came with hunting practices. And groups grew. It was more efficient. How *desire* evolved in these groups is the tantalising question. And this is where the Girard notion of mimetic rivalry becomes relevant.

I digress (which has now ended) for two reasons. First is the uncanny perspective of our long ancestry and our own tiny blip of a presence in history. Yes on the one hand forty thousand years ago is not all that long. Long but not THAT long. Its not like the perspective of sea slugs which goes back millions of years. Tens of millions of years. Actually hundreds of millions of years. The Cambrian explosion was over 500 million years ago. And two, that I have come to think there is almost no context in which we, as humans, do not tend to cluster together in ever larger groups. And that built into the psychic formation of — at least kinship groups — is something like an Oedipal narrative. But even if this is not quite true, and I don’t know what I think, really, there is a phylogenetic narrative or story. I suspect Freud was more right than not.

“Just 10 years ago, the first nuclear genome was meticulously reconstructed from three genetically identified females at Vindija; it revealed that, rather than ousting Neanderthals from Eurasia, we had in fact interbred with them. In the decade since, recognised periods of contact now number at least four and perhaps seven or more, going back beyond 200,000 years ago. Most intriguingly, something of the dynamics is visible. In some earlier instances, Neanderthal women had the children of H sapiens men, but the later interbreeding after 60,000 years ago tells a different story. Nobody today has mitochondrial DNA like that in Neanderthals and, since it’s passed only maternally, this implies that interbreeding was more often between their men and our women.”

Rebecca Wragg Sykes (Sheanderthal)

Tomb chapel of Hetepherakhty (Old Kingdom, harpooner hunting fish)

It is worth quoting this, too, from Sykes excellent book on Neanderthals:

“across the Atlantic, a black boy was born. Raised in a British Caribbean colony, Samuel Jules Celestine Edwards’ enslaved parents had been freed less than three decades earlier. Aged just 12 he became a stowaway, spending the 1870s travelling the world, before landing in the northern English industrial city of Sunderland. By the 1890s he’d gained a theology degree, was studying medicine and had become a respected and hugely popular evangelical and temperance lecturer. As if that were not enough, he was also a biographer, the first black editor in Britain (of Fraternity, the journal of the Society for the Recognition of the Brotherhood of Man) and founder of a magazine, Lux. Staunchly socialist and anti-imperialist, Edward’s lecture tours drew massive audiences as he spoke eloquently on emancipation and anti-colonialism. More particularly, he noted the way that evolutionary science was racist, promoting comparisons of black people to baboons. In an 1892 article entitled ‘The Negro Race’ – written in-between the Neanderthal discoveries at Spy and Krapina – he made the profound observation that, rather than indicating black or Aboriginal peoples were separate sub-human races, the increasing numbers of hominin fossils implied precisely the opposite. All peoples[…]”

Rebecca Wragg Sykes (Kindred)

Besides being just a remarkable story, it touches on the political biases on our view of the past. Even the very ancient past. And these political biases (including racism) are intimately related to the issues of desire. They are acutely related to the writing of history.

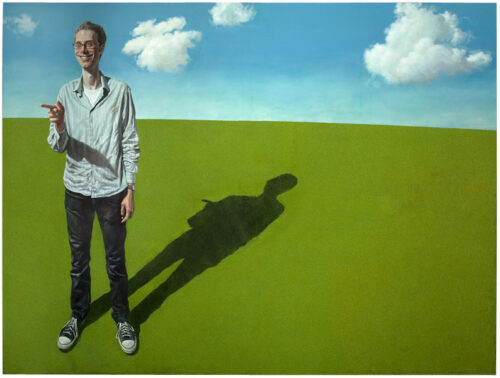

Stuart Pearson Wright

“Let us start with the parallel which exists between the method of sexual intercourse and the structural formation of the genitalia, on the one hand, and the aquatic mode of existence followed by a land-dwelling and air-breathing manner of life on the other. “In the lower animals”, we read in the Zoology of Hesse and Doflein, “in which eggs and sperm are simply discharged into the water, where fertilization then takes place, we recognize no specific behavior on the part of the individual as preceding this discharge.” The higher we go along the path of evolution, however-that is, in the terms of our own conception, the more complicated the experiences which the history of the race looks back upon-the more carefully is provision made to assure to the germ cells a favorable environment. At all events, the development of external genitalia takes place quite suddenly with the revolutionary development seen in the Amphibia. The latter are still devoid of copulatory organs in the proper sense, to be sure; these make their first appearance in the Reptilia (the lizard, the turtle, the snake, the crocodile); but a kind of coitus per cloacam, a pressing of the male cloaca against, or its intrusion into, that of the female, is already present in the frog. { } This course of evolution exhibits a certain analogy with the phases of development of the erotic reality sense in the individual, as we attempted to describe these in an earlier place. For the at first merely groping effort of the male animal to introduce a part of its body as well as its sexual secretion into the uterus reminds us of the attempts of the child, awkward and clumsy as they are in the beginning but pursued with ever increasing energy, to obtain by force, with the help of his erotic instinctual organization, a return to the maternal womb, and to reexperience, at least in a partial and symbolic sense, and at the same time to nullify, the process of being born. This view corresponds also with Freud’s conception, in accordance with which we may perceive in the curious behavior which characterizes procreation in the animal kingdom the biological antecedents both of the various ways in which infantile sexuality manifests itself and of the behavior of perverts. “

Sandor Ferenczi (Ibid)

Gillian Carnegie

Ferenczi’s book, which has remained a polorizing text in some quarters, but was also the most radical psychoanalytic theory ever written. And Ferenczi was quite concerned with trauma, in which he found something unknowable. The fact it cannot be anticipated meant it was also unbearable and unfathomable. In Thalassa he is positing the desire to return to the womb as a primary factor in human life. And that this oceanic memory of the womb is also recapitulating human history, our species traumatic transition from sea to land, and that these primordial structures of experience colour all later experience. Our deep biological past is being theorized — and in which science and poetry merge.

Jay Frankel, in a nice intro to Ferenczi’s book writes ” In his key 1968 text “The Shell and the Kernel” Abraham reflects on how “one is struck, as soon as Freudian terms are related to the unconscious Kernel, by the vigor with which they literally rip themselves away from the dictionary and ordinary language …[to]… no longer [follow] the twists and turns (tropoi) of customary speech and writing” . Symbols (from a patient, text or theory) are always fragments, therefore, separated from an original sense of unity that Abraham describes in his 1974-75 “Seminar on the Dual unity and the Phantom” in terms of a metaphor. “Every symbol is originally a metaphor,” he states, enjoined in a unity that is only ever a fiction and “having lost one of its parts, the metaphor becomes a symbol” (“The Seminar,” 15). The action of the symbol is to seek the complement that will reveal its truth in meaning. The process of becoming meaningful, however, is always metaphorical (Abraham describes the joining of symbol with its complement as metaphorisation) and this precludes any notion of a priori truth that can be revealed in its immanence. The excavation of a symbol’s history, and thus its reason for being (in the clinic, this is how the symptom is understood) becomes a translation where elements of a meaningful past are interwoven with unknowns that disrupt the continuity of a neat narrative.”

Jay Frankel (Translating the Psychoanalysis of Origins: Reflections on Nicolas Abraham’s “Introducing Thalassa” and Sándor Ferenczi’s Theoretical Legacy)

This was to have an influence in Lacan, certainly.

“Implicit in the word “Thalassa” (From the Greek for “sea”) Ferenczi describes the foundational trauma of our sexual life as desiccation. Birth ejects the infant from a blissful state of suspension in the amniotic sack in which unity with the mother as environment and provider is experienced concretely.”

Jay Frankel (Ibid)

Marcello Venusti (1550)

But for Ferenczi birth is not the original trauma here. It is itself a repetition of species trauma, the hardships and catastrophes of (for example) the receding seas, the transition to land, which was necessarily deeply traumatic and painful. This for Ferenczi was our biological unconscious. Birth is repetition. And here is why Freud sensed or intuited the profound significance of repetition. It is why theatre rehearsal is so inherently deep an experience. And the cultural (technological) mediation of repetition is so problematic. And our repetitive obsessiveness is highly sexual. The recapitulation is erotic, it is not Puritanical. The fascist mind fears moistness. The community, the socialist and the artist desire the moist. They, in fact, fear the arid. Again, this was shown perfectly in Theweleit’s Male Fantasies.

“It becomes apparent through a consideration of ritual’s form that ritual is not simply an alternative way to express certain things, but that certain things can be expressed only in ritual.”

R.A. Rappaport (Ritual, Sanctity, and Cybernetics)

This is Jan Kott discussing Lear. This is all serious theatre discussions and all discussions of tragedy. Benjamin said nearly the same thing about Trauerspiel. In a sense this is fairy tales, too. Ritual expresses something of the trace elements of Ferenczi’s biological unconscious. All ritual does. Perhaps microscopically in places, but I believe its there.

I had thought to write part two of Intro to Cinema, and I will, but I feel this post, too, should have a second part. We all long for home. But the impossibility of getting home is partly that we cannot finally know what constitutes home. A return to the oceanic womb beckons but that is not possible. Our mothers are gone. Our homes today no longer feel much like home. The morbid symptoms or phenomena is our homelessness, our exile. The literal crisis of homelessness is embodying the symbolism. Israel is carrying out the allegory of planetary guilt. They are Cain, and they are the also the counter revolution. The curse of Cain was in part an exclusion from the family. The paralysis that is not stopping the slaughter is another parable. Guilt will multiply.

William Blake (Satan over Eve, 1795)

“In any event, the recapitulation of the whole story from Genesis to Apocalypse. In Ferenczi’s apocalyptic theory of genitality the sexual act is a historical drama, a symbolic reenactment or recapitulation of all the great traumas in the history of the individual, of the species, of life itself. Psychoanalytic time is not gradual, evolutionary, but discontinuous, catastrophic, revolutionary. The sexual act is a return to the womb. But the separation of mother and child is a silhouette of the separation of life from the sea out of which it arose; and of the separation of life into two sexes; and of the separation of living from life-less matter. Birth really is from water; the womb really is an introjected, incarnate, ocean. “The mother would, properly, be the symbol of and partial substitute for the sea, and not the other way about.” In copulation the penis really is a fish in water. Symbolism is “buried and otherwise inaccessible history.”

Norman O. Brown (Love’s Body)

“Therefore hath the curse devoured the earth, and they that dwell therein are desolate: therefore the inhabitants of the earth are burned, and few men left.”

Isiah 26:6

Nothing happens for the first time. And it was Pascal who said “all appearance indicates neither a total exclusion nor a manifest presence of divinity, but the presence of a God who hides himself. { } God being thus hidden, every religion which does not affirm that God is hidden, is not true;…”

(Pensees)

last word from Norman O. Brown:

“Overthrow the importance principle; turn it upside down. Put down the mighty from their seats, and exalt them of low degree. Every throne a toilet seat, and every toilet seat a throne. Psychoanalysis, the visionary sansculottism.”

(Love’s Body)

To donate to this blog use the paypal button at the top of the page (or Stripe if using Substack). This also goes to keeping the Aesthetic Resistance podcasts going.

And this link ties in Rousseau with The Dawn of Everything. An 8 minute read,

https://www.byarcadia.org/post/wicked-liberty-the-origins-of-rousseau-s-discourse-on-inequality

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aquatic_ape_hypothesis