Lieko Shiga, photography.

“The sense of the world must lie outside the world. . . . When the answer cannot be put into words, neither can the question. . . . The solution of the problem of life is seen in the vanishing of the problem.”

Ludwig Wittgenstein (Tractatus)

“Perhaps our age has gone to analysis not to be loved or get cured, or even to Know Thyself. Perhaps we go to be given a case history, to be told into a soul story and given a plot to live by. This is the gift of case history, the gift of finding oneself in myth. In myths gods and humans meet.”

James Hillman (Healing Fiction: On Freud, Jung, Adler)

“…culture is an empirical reality of the first order in human life—that it, in the most profound sense of the word makes us human and defines human experience.”

Liah Greenfeld (Mind, Madness, Modernity)

“…it happens that a letter does not arrive at its destination.”

Louis Althusser (The Discovery of Dr. Freud)

“We must emphasize with all decisiveness that Christianity did not grow out of Judaism but developed in opposition to Judaism.”

Ludwig Müller, Bishop to The Third Reich 1933

“Psychoanalysis can do nothing against bullshit.”

Elizabeth Roudinesco (interview, Radio France)

I was interviewed the other day for a documentary on Ork Records, and the story of CBGBs. Terry Ork (aka Noah Forde, Bill Terry, Terry Collins) was a close friend of mine and I was close to that entire narrative. But I had little interest at the time, or now, in punk rock, or figures like the, now, late Tom Verlaine (aka Tom Miller), or Richard Hell (aka Richard Meyers) or Patti Smith. Ork for all his flaws, and they were many, was a kind of genius. And it is ironic that his his role in punk is how he is now remembered. For that was among his least interesting projects. It was the least interesting for him, too. But the interview reminded me of how culture has changed since the 1970s. The New York I arrived at in 1969 no longer exists, in fact its shadow no longer exists. And so today that era has taken on its own sort of mythology. A mythology that bears only scant resemblance to the reality. The greatest actual change is the loss of literacy overall. Today very few people read. They barely read magazines or even texts on social media. This is a reminder of why TikTok or Instagram are so popular. They are anti-literate.

It is no accident that in Europe today, amid massive militarization, you find not a single party in any country I can think of, in which one could vote to express opposition to the US/NATO war against Russia. You have stagnating or falling wages, a rising cost of living, and a critical shortage of low cost housing, especially for students or low wage workers. Everything today called *left* are anti working class petit bourgeois parties or influencers who completely neglect U.S. imperialism. The identity based politics of the liberal left in the U.S. are profoundly reactionary in the end, and serve as little more than distraction.

The larger implications of the collapse of culture and art is worth considering here.

Bernard Plossu, photography.

Liah Greenfeld has suggested that the onset of *nationalism* altered how people framed their existence.

“The essence of this ideal is the demand for the embodiment of two principles: the principles of fundamental equality of membership and of popular sovereignty; the nation, in other words, is defined as a community of equals and as sovereign. Equality in shared sovereignty may be interpreted as individual liberty, and was so interpreted in England as well as in societies that closely modeled their nationalism on its example later. But equality could also be interpreted as collective independence from foreign domination. ”

Liah Greenfeld (Ibid)

Now, Greenfeld represents a curious mix of both insightful historical observation, and of psychological implications and a weirdly reactionary view of the political. In any event, I think the idea of madness as traced back to the 16th century is germane to contemporary western life. Madness, at first an English phenomenon (even referred to as ‘the English malady’ for a time) seemed to spread (to continental Europe, first in France) as nationalism arrived, too.

“This psychophysical, or mind/body, assumption has been at the root of the central philosophical problem in the Western tradition since the time of Plato, because no satisfactory solution could be found to the connection between the two heterogeneous expressions: both are a part of every human’s experience and clearly influence each other in it, but it is impossible to account for this coexistence and influence either logically without contradicting this experience or, for that reason, empirically by showing how precisely one translates into the other. { } Within this philosophical framework, my argument that culture (an ideational, symbolic, nonmaterial phenomenon) causes a biologically real (material) disease appears quite incredible. This lack of credibility is, in the first place, a function of the credit given today to the materialist interpretation of the psychophysical relationship. But the real problem lies not in one or another interpretation, but in the assumption of this relationship itself. In most areas of life and of science this philosophical assumption is of no importance—it may exist in the back of our minds but is very rarely, if ever, brought to the surface, and does not in any way interfere with our daily activities. In psychiatry and human neuroscience, however, it forms an impassable obstacle to the understanding of the very phenomena those engaged in these fields aim to understand, for there is no more logical possibility, in the framework of the dual mind/body view of reality, of translating material events occurring in the brain into the symbolic events of human consciousness, than in translating a symbolic cause into a material effect.”

Liah Greenfeld (Ibid)

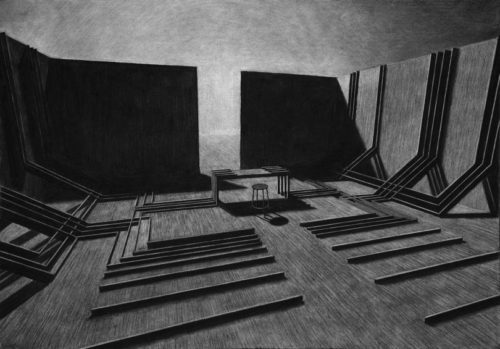

Rosella Agostini

Greenfeld’s premise is summed up here: “The reason for the dysfunction of the acting self lies in the malformation of identity.”

Liah Greenfeld (Ibid)

And this is very relevant to the contemporary eruption of mental illness. And in turn segues into ideas of culture. And that is basically my premise. Identity and by extension culture. The *nationalism* idea is intriguing though I think calling it capitalism might be more accurate. But this becomes a nuanced discussion. It is both. Capitalism must entail nationalism, but identity malformation is likely more the result of exchange value, reification, and commodification than it is nationalism. By the time Adam Smith wrote his treatise Wealth of Nations, capitalism was already well established.

Today Lindsay Graham cackled about Russians dying, and said (regarding the U.S. war with Russia) ‘it’s the best money we ever spent’. By *we*, he meant the U.S. This is the voice of a sociopath. Nobody seems to notice. Arnold has a new TV series where he plays a retired (sort of) CIA operative. In the pilot he recalls how he had the son of a terrorist he was holding in custody taken off the compound before throwing the son’s father, the terrorist, off a cliff. ‘I was trying to be nice’ Arnold says. It’s a moment of comic relief. Nobody notices. I can tell you from some personal experience that Schwarzenegger is a sociopath. Nobody notices or cares.

“For not only was Freud’s discovery, as will be seen, reduced to disciplines that are, in essence, foreign to it (biology, psychology, sociology, philosophy); not only have numerous psychoanalysts (notably of the American school) become accomplices of that revisionism; but in addition, that revisionism has itself objectively served the prodigious ideological exploitation whose target and victim psychoanalysis has been.”

Louis Althusser (Writings on Psychoanalysis)

Now, I have always had a somewhat ambivalent relationship to Lacan. It’s partly that there is the unfortunate Zizek association, but it’s also that so many Lacanians are terrible. But Althusser is right when he points to Lacan as a kind of recuperative reinvention of Freud, the core serious radical Freud.

Sarah Moon, photography.

“ Marxists, who know from experience what distortions Marx’s adversaries imposed on his thought, can understand that Freud may have been subject in his way to the same fate and what the importance of an authentic “return to Freud” is.”

Louis Althusser (Ibid)

And understanding this is important for any investigation of contemporary societal sickness. And I have taken note over the last few years, but especially over the last two or three, of the seemingly intentional conflations regards ideology overall, as a topic, and in particular the distortions regards communism, socialism, and Marxism. One of the most popular and seemingly durable conflations is that of fascism and communism. From whence it comes remains a bit of a mystery. There are a lot of specious pseudo histories (Anthony Sutton is one) but it’s also the structural antisemitism one finds resurgent today (see CJ Hopkins latest https://consentfactory.org/2023/05/28/the-anti-anti-semitism-follies/ )

So, I want to track Greenfeld’s analysis, as well as Althusser’s Lacanian critique, and also my own set of footnotes on both. Althusser saw Lacan’s *return* to Freud as a return to Freudian theory. And as a corrective to the revisionisms of American psychologism and behaviorism. This is really very close to what Russell Jacoby did in his book Social Amnesia.

“What is the object of psychoanalysis? It is that with which analytic technique has to deal in the analytic practice of therapy, that is, not the therapy itself, not that allegedly dual situation in which the first phenomenology or morality to come along can find the wherewithal to satisfy its need, but the “effects,” prolonged in the surviving adult, of the extraordinary adventure that, from birth to the liquidation of the Oedipus complex, transforms a small animal engendered by a man and a woman into a little human child.”

Louis Althusser (Ibid)

Sarah Anne Johnson

And Althusser’s defense of the density and difficulty of Lacanian language is also germane here. I say this because I often am criticized (or my writing in this blog) for a style that is discursive and poetic. Adorno is thus criticized as well, not that I am to compare myself with either. But the necessity of difficult language will naturally segue into discussions of allegory. And I continue to feel that theatre has reached that allegorical place where, perhaps, aesthetics itself is in need of reconceptualization.

“For Benjamin, allegory was distinguished by its unique engagement with two central aesthetic categories: time and totality—categories which writers and critics from Goethe to Yeats have marshaled against allegory and in favor of the symbol. In the symbol, time is collapsed into a transcendent moment, in which the essence of the artwork, the marriage of form and content that constitutes its totality, is manifested in a single one of its elements: the transient image. Allegory, conversely, is durational in nature and in disposition: time becomes its defining feature as well as its object. Instead of provoking metaphysical insight through what Benjamin calls a “mystical instant” (Benjamin), allegory accumulates meaning through a process of accretion. “The distinction between the two modes is therefore to be sought in the momentariness which allegory lacks,” Benjamin notes, “There [in the symbol] we have momentary totality; here [in the allegory] we have progression in a series of moments”.”

Roger Bechtel (Hamletmachine and Allegorical History; The Cultural Politics of Heiner Muller)

I sense that because of the erosion, or just forgetting of history, that allegory has increased in value and symbolism declined. Allegory in its durational aspect necessitates an historical perspective. A meditation on history. And if one is examining the malforming of identity (per Greenfeld) then how history is viewed becomes even more important. Now, there is also a sense in which allegory is that which erases history (see below). It is the conduit through which pseudo mysticism runs, from the worst of Jung to New Age crystal healers. But sticking with Freud for a bit longer….

“Freud had already said that everything was dependent on language. Lacan specifies, “The discourse of the unconscious is structured like a language.” In his great first work, The Interpretation of Dreams, which is not anecdotal or superficial, as is often believed, but fundamental, Freud studied dreams’ “mechanisms” or “laws,” reducing their variants to two: displacement and condensation. Lacan recognized in these variants two essential figures designated by linguistics: metonymy and metaphor. Hence slips of the tongue, botched gestures, jokes, and symptoms became like the elements of the dream itself signifiers inscribed in the chain of an unconscious discourse, silently (that is, deafeningly) duplicating, in the misprision of “repression,” the human subject’s chain of verbal discourse. Thus were we introduced to the paradox, formally familiar to linguistics, of a discourse both double and unitary, unconscious and verbal, having as its double field of deployment but a single field, with no beyond other than in itself.”

Louis Althusser (Ibid)

And this, in turn, branches off into Wittgenstein, among others.

Levi Van Veluw

Allow me a longer quote here from Althusser. And this is the period where his writing becomes more difficult, often incomprehensible, really. A period of incipient madness.

“To indicate things in a few brief words, let me note to this end the two great phases of the transition: (r) the moment or phase of the preOedipal dual relation, in which the child, dealing only with an alter ego, the mother, who scans his life with her presence (da) and absence (fort),3 lives this dual relation in the mode of the imaginary fascination of the ego, being himself that other, some other, every other, all the others of the primary narcissistic identification without ever being able to take, in relation to either other or self, the objectivizing distance of a third party; (2) the moment or phase of the Oedipus complex, in which a ternary structure irrupts against the ground of the dual structure, when the third party (the father) combines as an intruder with the imaginary satisfaction of the dual fascination, overthrows its economy, shatters its fascinations, and introduces the child to what Lacan calls the Symbolic Order, that of the objectivizing language that will allow him finally to say “I,” “you,” “he,” or “she,” which will thus allow the little being to situate himself as a human child in a world of adult thirds.”

Louis Althusser (Ibid)

This is Lacan’s law of the symbolic.

“When this transformation occurred, the emergent phenomenon of the mind was in place, and, being autonomous—self-regulating, self- sustaining, self-generating, and self-transforming (like life)—it caused itself. It is absolutely impossible to reconstruct how this happened. But it is possible to understand—i.e., deduce logically—what happened. A very large plurality of the signs used by Homo sapiens, because of the biological constitution of this species, were vocal signs. The ability to articulate sound allowed for playing with it. For hundreds of thousands of years, Homo sapiens cubs—children—probably had a lot of fun with making various meaningless noises, noises which could be intentionally produced, as if one was reading or communicating a sign, but did not signify anything. Then, 20,000, maybe 30,000 years ago, one particularly sapiens homo recognized that sound signs could be intentionally articulated, and intentionally articulated signs are symbols.”

Liah Greenfeld (Ibid)

Elise Toide, photography.

“In the foregoing case the mechanism of projection is used to settle an emotional conflict; it serves the same purpose in a large number of psychic situations which lead to neuroses. But projection is not specially created for the purpose of defence, it also comes into being where there are no conflicts. The projection of inner perceptions to the outside is a primitive mechanism which, for instance, also influences our sense-perceptions, so that it normally has the greatest share in shaping our outer world.”

Sigmund Freud (Totem and Taboo)

Greenfeld writes that nationalism increased choices for people. One could have feelings of ambition and aspiration. So in a sense this is saying that the myth of capitalism, as it has come down to us, is what generates a particularly modern anxiety. Or frustration. Or disappointment. For class struggle is what is left out of her analysis. Class altogether, in fact. Poor kids in Baltimore or on the Mexico/Arizona and Texas border do not have the same aspirations as wealthy children of Washington diplomats, say.

In what way can we speak of propaganda and how it works on the developing mind? Or of myth, possibly. But here it is worth examining why the mind in antiquity, as contemporary westerners see it, remains so distant and obscure. And here I want to digress a moment to look at just one aspect of this, that compares allegory with *figura*.

Elsa Egon

And it is to Erich Auerbach that one must go. As an aside, Auerbach’s remarkable study, of what he called, literary presentations of reality, his book Mimesis, is one of the most beautiful works of the 20th century. And perhaps one of the two or three greatest pieces of literary criticism ever written. It additionally, as Nicholas Howe notes, “… carries an exemplary, even romantic glow, from the poignant circumstances under which Auerbach worked”. That he wrote this book without a reference library, and largely from memory is remarkable. That he wrote as a Jewish exile in Istanbul during the Nazi reign in Germany is even more remarkable. And later, when living and teaching in the U.S., Auerbach never revised or annotated the original text of Mimesis, preferring to leave it as a testament to the intrepid scholar in exile. (Nicholas Howe, The Figural Presence of Erich Auerbach)

But back to the point at hand.

“The development of figural language, with which the Church had given dignity to the narration of everyday phenomena, resulted in a kind of realism devoid of impact on the world of social life, as it always referred to biblical similes. Every event on earth would have its analogue in God’s plan for mankind; { } A new form of realism emerges in Renaissance novels, which gives an autonomous dignity to certain aspects of worldly life (especially eroticism and the vicissitudes of relations between the sexes). To free himself from the theological straitjacket of medieval realism, in which everything in earthly life can only be narrated because it points to something corresponding in another world, it was not enough for Boccaccio to simply describe the experience: it was necessary to infuse it with good doses of fantasy. In the absence of another world to which one could delegate the significance of what happened in this one, it was necessary to endow it with depth, with something of mystery. There would be the origin of modern narrative formations: a realism made possible by an unprecedented release of human creative forces, that is, by a form of delirium…”

André Jobim Martins (When Literature Created Reality, translated from Portuguese by Google)

“The strangeness of the medieval view of reality has prevented modern scholars from distinguishing between figuration and allegory.”

Erich Auerbach (Figura)

Virgile Ittah

Without getting too deeply down the philological rabbit hole here, though I admit I enjoy that particular hole, the point is really that in the time of Cicero, the word *figura* might well be translated as figure, or atoms, or stamp, or seal from a stamp, or copy even. The difference between figura and allegory is important. Auerbach wrote an interesting couple essays himself on what he called *national spirit* (volkgeist).

“The idea of a national spirit (Volksgeist) involves the claim that poetry is the first language, the mother tongue of the human race, and that it emerges spontaneously out of the depths of the national soul. It is an idea conceived as both universally human and as proper to the traditions of an individual nation. It presumes that when- and wherever a human community becomes conscious of itself as human, poetry emerges as the expression of this consciousness. When- and wherever this happens, poetry takes on a form appropriate to the specific nature and fate of each individual nation. Moreover, this idea applies not only to poetry in the narrow sense of the word, but also to all modes of civilized behavior. For, in those prehistoric times when poetry developed as the original language of the human race, all civilized behavior was poetic: religion, law, political institutions, art—and of course language too, since poetry was humanity’s first language.”

Erich Auerbach (The Idea of the National Spirit as the Source of the Modern Humanities)

This is very close to what Greenfeld is saying.

“…a national spirit and its manifestations develop organically alongside both the nature and the fate of a particular nation as long as its development continues in an undisturbed and unhampered way.”

Erich Auerbach (Ibid)

But, as Auerbach notes, there are always interruptions, things are never undisturbed. Then Auerbach writes a remarkable paragraph:

“Reason, when it is of this calculating, rule-imposing sort, is thus the archenemy of the national spirit, while the most natural flowering of mankind’s creative powers, those of the imagination, takes place in prehistoric times, when reason is not yet fully formed. Accordingly, the way to heal and restore a culture that has been undermined by the calculations of reason is to return to its sources, to the national spirit of prehistoric times.”

Erich Auerbach (Ibid)

Yann Mingard, photography.

Auerbach notes the difficulty of finding the origins of modern national spirit.

“The idea of a national spirit first appeared among those who were involved in the pre-Romantic movements of the eighteenth century as a reaction against the normative aesthetics that dominated at the time, the tendency and taste associated with French Classicism. More generally, it was a reaction against the rationalistic reform movements of the Enlightenment,”

Erich Auerbach (Ibid)

He actually goes on to identify Vico, in the late Baroque, as a significant source of national spirit (or nationalism?). From Vico it spread to the opponents of the French Revolution, it spread to England, but most significantly, for Auerbach, to Germany. And it was perfected, in a sense, distilled, in the Germany of Herder and Möser, Jacob Grimm, and Goethe. And it came to dominate the 19th century. And this branch of Romantic Historicism reached its zenith in Hegel (of course). And with this national spirit came ideas about the Middle Ages, about the poetry and legends and folklore of the earliest period.

“For since no one could actually observe the medieval national spirit at work (there was very little evidence of its activity, its dating was unreliable, and its interpretation a matter of debate), there was ample room for conjectures of all sorts. The reaction began to set in around 1900, inspired partly by the ambition to compete with the precision of the natural sciences and partly also by French nationalism—for it seemed that in Europe, the “epic” national spirit meant the German national spirit. In its campaign against the theory of a national spirit, this early form of positivism took as its first and most important target the French chanson de geste.”

Erich Auerbach (Ibid)

Erich Auerbach, 1919

Auerbach is suggesting a cleaner more historically sophisticated version of what Greenfeld has said.

“The history of the world has seen to it that the idea of a national spirit developed by the pre-Romantics and Romantics awakened an understanding for the individuality of nations and their cultures. That is, hermeneutical perspectivism, on which all historical humanistic disciplines are based, grew out of this idea.”

Erich Auerbach (Ibid)

Auerbach suggests the perspective born of the idea of national spirit is the most significant idea of western civilization. The historical perspectivism was absent in antiquity, or at least masked in a sense. And here Christianity looms:

“Nevertheless, it seems to me that a kind of proto-perspectivism can be located in the way the Christian historical imagination organized time as a sequence of epochs running from Original Sin through to the Coming of Christ, and from there to the Resurrection and the Last Judgment. This kind of historical sequencing, thinking in stages, is far less mystical —and much more historically informed—than the corresponding divisions of time that one finds in classical antiquity.”

Erich Auerbach (Ibid)

Forgive this exceedingly long digression (of sorts) but this idea is hugely important and clearly has found contemporary versions in the work of people like Greenfeld. And Auerbach also expresses some surprise that the Renaissance brought forth no historical perspectivism. There was however, Dante (an obsession for Auerbach it should be noted). And in The Divine Comedy one sees the core idea of eternal salvation, and an almost cosmic perspectivism. Yet, and I have noted this, too, there is something very NOT modern about Dante. And this impenetrable anti-modernism in his masterpiece is a good part of its continuing allure. Dante and Shakespeare. Probably, in the end, it is to these two that one must always return (sic).

The final sentence in this neglected short essay of Auerbach’s goes thus…

“The other movement that stood in the way of historical perspectivism was almost even more powerful than Humanism, because it was far more widespread. This was the revival of the old conceit of an absolute human nature.”

Erich Auerbach (Ibid)

Enrico Castellani

And this elegantly segues back to Freud, Althusser, and capitalism. There is, however, an additional aspect to Auerbach, and that is his analysis of *figura* and of allegory, of reality as its presented in literature (and culture) was an analysis that resisted the massive tide of fascism in the 1930s, and the Aryanization of philology. And by extension, philosophy.

“Based on the legends and mythologies of “Blood, Volk and Soil”—Blut und Boden, the major slogan of Nazi racial ideology which focused ethnicity based on blood, folk and homeland, Heimat—Aryan philology was a unique German racist, chauvinist and anti-humanistic philology, which strove to fashion new Aryan origins of the German people, to shape a new Germanic or Nordic Christianity, to reject and eliminate the Old Testament from the Christian canon, and thus to construct new origins, aims and goals, for the history of the German people in particular and of Western civilization in general. Much of Auerbach’s works, but most specifically “Figura” and Mimesis, were directed against the racist, chauvinist and anti-Semitic premises of Aryan philology.”

Avihu Zakai (Erich Auerbach and His “Figura”: An Apology for the Old Testament in an Age of Aryan Philology)

The distinction between figura and allegory is that *figura*, born in the antiquity of early church fathers, is an exegesis that is enlisted in efforts to prove the validity of Christ’s redemption. The figural perspective culminates in apocalypse.

“In “Figura,” Auerbach strongly insisted on a firm and rigid demarcation between “figura” and “allegory,” or the Index figurarum and the Index de allegoriis, thus drawing a clear-cut contrast between “allegory, in which figure is feigned to illustrate a given proposition, and figura, in which both terms, the figure and the figured, are deemed real.” Basically, Auerbach explains, figure “differs from allegory in that allegory involves an abstract sign that leads beyond itself rather than to another real historical being” as in the case of figure. Figura thus implies realism, and vice versa. Later on in Mimesis, Auerbach explained that one of the main differences between allegory and figura is that allegory moves “horizontally” on earth, or in the historical realm, while figura “vertically,” thus connecting Heaven and earth or the sacred and the secular. Allegory is “horizontal,” because it deals with the realm of “the temporal and causal,” while figura is vertical since “both occurrences are vertically linked to Divine Providence .”

Avihu Zakai (Ibid)

Now why is this important, in relation to contemporary insanity, and the loss of reason? It is important (and here one sees the seeds for that famous first chapter in Auerbach’s Mimesis, on Homer and the King James Bible) because the seeds of regression that were carried along in the Enlightenment project, were seeds that existed in a curious dialectical relationship with Western rationality. The unconscious that Lacan focused on in his reinvention of Freud is part of an existential world view that positivism and scientism tries to subvert.

Damien Drew, photography.

*Figura* connects two figures in time. It posits history. Allegory, for Zakai, devalues the historical record. I’m not sure that’s true or that Auerbach saw it that way, but allegory does imply an unconscious timelessness. Allegory is Freudian in that sense. And one sees in secular literature, from Shakespeare through Melville and Kafka and Dostoyevksy, the allegorical at work. However, the Nazi appropriation of the New Testament was an attempt to erase history. To deny the Old Testament (A judaic book) and its *figural* relationship to the New. The figural was bastardized, as it were, later, by Enlightenment science and a rigid rationality that narrowed its focus to exclude the allegorical. The Reich looked to erase history and insert its own mythology. It used an anti-figural form of allegory, perhaps, but it was not the allegory of pre Christian thinkers or writers.

“The Alexandrian allegorical school, which was influenced by the thought of the Hellenistic Jewish world in Alexandria in which Philo and others viewed the Bible in Platonic terms as essentially an allegory, which was later Christianized by Origen Adamantius of Alexandria in the third century, and the figural school of Tertullian and Augustine.”

Avihu Zakai (Ibid)

The Nazi mythos made use of Christianized interpretation, AND of the idea (but less the reality) of Greek thought. Heidegger’s metaphysical nazism was a form of allegoricalizing that privileged a Christian perspective, however deformed. Zakai rightly emphasizes that Auerbach’s contentions are not simply philological but are ideological as well.

“…history, with all its concrete force, remains forever a figure, cloaked and needful of interpretation. In this light the history of no epoch ever has the practical self-sufficiency which, from the standpoint both of primitive man and of modern science, resides in the accomplished fact; all history, rather remains open and questionable, points to something still concealed, and the tentativeness of events in the figural interpretation is fundamentally different from the tentativeness of events in the modern view of historical development. In the modern view, a provisional event is treated as a step in an unbroken horizontal process; in the figural system the interpretation is always sought from above; events are considered not in their unbroken relationship to one another, but torn apart, individually, each in relation to something other that is promised and not yet present. Whereas in the modern view, the event is always self-sufficient and secure, while the interpretation is fundamentally incomplete, in the figural interpretation the fact is subordinated to an interpretation which is fully secured to begin with: the event is enacted according to an ideal model which is a prototype situated in the future and thus far only promised.”

Erich Auerbach (Figura, 1938)

This is a profound paragraph, really, for it situates the contemporary scientistic logic of capitalism in a broader historical context. Today, the maladjusted are seen in terms of symptoms. And symptoms are to be *fixed*. Even the individual history of the patient becomes irrelevant. Critics have often complained that Auerbach minimized allegory. But Zakai points out that Auerbach’s idiosyncratic distinctions are ideological. Auerbach wrote against the backdrop of Hitler.

The truth is that Auerbach was clearly aware that his definitions of *figura* were pretty much what is elsewhere called typology. But that was not the point. In other words, there is allegory and there is allegory. In the historical context of the 20th century (and today perhaps) his distinctions have importance. The Reich employed a reductive allegory to erase Judaic history, and among the implications was both a devaluing of allegory itself, and certainly a devaluing of figura. The Third Reich manufactured a kitsch paganism and an ersatz myth of Aryan grandeur. It racialized history and layered its technological fetishizing with these kitsch historical readings.

Today in adjustment therapy, and in the solutions of pharmacological psychiatry, one is seeing the erasing of history, albeit individual history. This psychiatry is a positivist ahistorical anti figurative and anti allegorical perspective on a patient’s personal stories. The self help therapy culture does to the individual history what the Reich did to western antiquity.

Diana Thorneycroft

“This historical lesson applied not only to early Christianity but to Nazi Germany as well. Thus, although the above words referred to the struggle between the “Judaeo-Christians” and Paul’s figural interpretation in early Christianity, Auerbach must have had in mind as well the proponents of Aryan philology in his own time. In other words, his acute awareness of the problem of eliminating the Old Testament in early Christianity may well arisen because of attempts to eliminate the Old Testament in his own time in Nazi Germany.”

Avihu Zakai (Ibid)

The contemporary comment threads to various pseudo left writers (Matt Taibbi for example, often an excellent journalist but hopelessly confused about what constitutes ‘the left’) and one sees the legacy of historical erasure that Auerbach agonized over. One sees it in the continuing conflation of fascism and socialism and communism. The loss of the radical core Freud is entwined with this as well.

“The cardinal feature of nationalism—which necessarily follows from the principle of popular sovereignty and underlies every other aspect of the national reality, including the fundamental egalitarianism of the national membership—is its secularism. { } This radical transformation was felt in England already in the early sixteenth century. The “modernization” of English (the addition of countless neologisms, reconceptualization of existing words, “and invention of new morphological constructions)—under way by its third decade, at the latest, reflected the fact. There existed no language to describe and express the new existential experience before: coming to grips with the new life, therefore, involved creating it. What we know as modern English—one, and not the earliest one, of modern vernaculars—is, in fact, the lingua franca of modernity. It encoded the new view of reality, enabling everyone who spoke it to experience life in the new way. Henceforth translation from English changed the nature of experience in communities of other languages as well. Modern reality thus arrived.”

Liah Greenfeld (Ibid)

Greenfeld points out Shakespeare’s sonnets as particularly secular. The word *mind* appears around this time. It is not in the English dictionary of 1499, but it is certainly prevalent in Shakespeare’s works. And it functions at first as a near synonym for soul. Gradually however the word *soul* loses its religious character. The word *aspire* begins appearing and *achievement*. The great expanding of the English vocabulary begins, really, in the late 15th century. And aspiration and achievement are suddenly very popular words. These are the words of capitalism, too. As is the focus on ideas of ‘productivity’.

John William Waterhouse (1874)

“ A vast new area was annexed to meaningful (i.e., human) life, a new existential dimension, and modern English both mirrored and was an instrument of its formation. What we are witnessing in tracing these concepts to their sixteenth-century beginnings is the emergence of entirely new semantic space—new areas of meaning and experience—semantic space that is central to our lives today.”

Liah Greenfeld (Ibid)

The other word that appeared at this time was *ambition*. And this would necessitate an entire volume unto itself. And clearly this is a quintessential word under Capitalism. But Greenfeld nicely moves on to a discussion of madness ( another word that became popular in the early 1600s) And the influence of, in particular, Foucault. This is a very fine chapter in Greenfeld, and tracing the usage and definitions and perspective on mental illness is worth reading in full. The first medical treatise, Treatise of melancholie was published in 1586 by Timothy Bright, an Anglican priest.

“The Treatise of Melancholie was “the most representative thesis upon melancholy and insanity of the Elizabethan period.” It was precisely at the time of the book’s composition, 1580s, that melancholy became “epidemic.” It continued for several decades. For some time melancholy men were so numerous in London that they constituted a social type, often called malcontent.”

Liah Greenfeld (Ibid)

Manuel Álvarez Bravo, photography

Bright’s treatise was to influence thinking on mental distress for several hundred years. Worth noting how many 17th century plays feature characters suffering melancholy –in Webster, Tourneur, Ford and Marlowe. And Shakespeare. Madness and the stage seemed remarkably suited to each other. Madmen were meant as a metaphor, largely, for disillusionment. And here one might consider an allegorical reading of Hamlet. It is also worth noting King Lear in this respect (and my experimental production in Poland were I had two Lears on stage the entire play, one speaking English and one Polish, might have been even more insightful than I thought).

“Does any here know me?—This is not Lear: / Does Lear walk thus? speak thus? / Where are his eyes? / Either his notion weakens, his discernings / are lethargied.—Ha! Waking? ’tis not so.—/Who is it that can tell me who I am?”

William Shakespeare (King Lear)

The definitions of schizophrenia found in the latest DSM are woefully inadequate, which even the authors of the DSM admit.

“According to the DSM-IV, the onset of schizophrenia usually occurs in the late teens to early thirties, with modal age of onset being eighteen to twenty-five for men and twenty-five to thirty-five for women. Men are believed to be more susceptible to the disease and face a worse prognosis. The disease is usually chronic, only 22 percent of patients having only one episode and no residual impairment. 35 percent have recurrent episodes, 8 percent have recurrent episodes and develop significant impairment, and 35 percent have recurrent episodes, develop a significant impairment, and the impairment is becoming worse with time. Seventy-eight percent, therefore, do not recover. The great majority never marry or have children, and most are unable to support themselves. Thirteen percent of diagnosed schizophrenics commit suicide.”

Liah Greenfeld (Ibid)

So, given these statistics, and given the statistics on use of anti-depressants, which I have posted before, there would seem to be a kind of collective denial in western cultures regards mental suffering. Ernst Rüdin, the Nazi physician who gassed a hundred thousand mentally infirm patients, is is still referred to for his earlier work on schizophrenia.

Simona Barreca

Now Deleuze and Guattari’s Anti Oedipus, Capitalism and Schizophrenia is not really about schizophrenia (nor is Jameson’s work on same). With that out of the way, it *is* obvious that advanced capitalism is having dire consequences in mental suffering for large chunks of the populace. And equally obvious that the early modern doctors of the mind (including a good many reformed Nazis) going back to the 17th century and onward, set the perspectival template for mental illness. And this feels close to the point of this entire posting: the Enlightenment, the so called Age of Exploration, the scientific revolution and the Industrial revolution were all expressions of the birth of nationalism/capitalism. And the science and a privileging of positivism and calculation were installed as institutional truths. And early on the European powers found expedient science to justify slavery and racial hierarchies. Class served as a model, in a sense. Class was the natural tension between those with surpluses and those without.

The corporate world today is decidedly not figural, but it is also not allegorical in any sense of the word. And identity, in a world of minimal literacy is reduced to highly transitory and ephemeral identifications (the click bait world of; which character in Friends are you? take this quiz. Which Barbie Doll are you? Which dead lead guitarist in heavy metal are you? etc etc etc). The clicks are not taken *seriously*. They are not actually *believed*. This however is a tricky proposition. Astrology is not believed, and yet it is. It is a belief in a certain register. This is postmodern belief. I think the only real authority to which the average citizen appeals is that of the scientific expert. Those so appealing could not define what *expert* means exactly, but its associated with countless semiotic signifiers (white coats, or offices in institutional buildings, titles, and institutional accreditation). Belief is fungible. It is shifting. History is vague, and associated with equally vague emotions.

“…the contemporary deployment of metaphysics (the constitution and deconstitution of juridical entities) as a means and modality of war. Guantanamo, for example, is in the business of producing terrorists. We have the intentional engineering of subjects: the terrorist and the sovereign subject by the carceral machine—the terrorist is retroactively engineered and the sovereign is proactively engineered. Where with Turing and the development of computers, subjectivity was decoded and simulated (that is revealed as a simulation), subjectivity is, with the integration of computers and their calculi into the web of life, encoded and simulated (that is projected as an actionable fact), as a driver of economy and of war. In a general sense we observe that from government sponsored nationalism, to character identification in Hollywood films, to the idea of the computer desktop or file, computational interfaces disbursed throughout the socius utilize retrograde modes of subjectification (orientation, suture, interface) as well as advanced techniques of assemblage and blurring to perform socio-economic functions whose larger consequences structurally exceed the understanding of the subjects posited, interpellated, fragmented, dis-/re-/al-located … and above all—above all (?)—functionalized in the informatic matrix that instantiates them.”

Jonathan Beller (The Message is Murder)

Torn Curtain (dr. Alfred Hitchcock, 1966)

In a sense, as literacy declines, and vocabularies shrink, the importance of allegory and metaphor increases. The scarcity of narratives with substance, with structure, results in an increased importance in the search. A search for what feels just out of reach. Here is the essential truth of Lacan, I believe. The unconscious, if structured like a language (per Lacan), will suffer from a kind of narrative starvation. This is contemporary schizophrenia I suspect. The instinctual desire for a lost or missing story. The search must become more frantic. More incoherent. More painful. Jameson is wrong when he writes (on Althusser):

“History is not a text, not a narrative, master or otherwise, but that as an absent cause, it is inaccessible to us except in textual form, and that our approach to it and to the Real itself necessarily passes through its prior textualization, its narrativization in the political unconscious.”

(The Political Unconscious)

It is exactly all those things. And this marks a perfect example of missing the point in Lacan. Of course history is not literally a text, but it is exactly a narrative. And the ‘absent cause’ of Jameson’s is also a narrative. The unconscious is structured as a language. But the key is language, not structure. And in a sense the unconscious IS a text, a story. The unconscious inscribes, and it speaks. And figura and allegory express the unconscious. These are the forms of the unconscious. And at this point it is safe to state the unconscious is ideological, as well..

“…to see the rise of computation not as introducing a crisis of value but as a response to a crisis within the domain of value and valuation—a revolutionizing of the productive forces whose measure has not yet been taken. Here the injunction would be to finally come to terms with the computational unconscious, or what Adam Smith called the invisible hand.”

Jonathan Beller (Ibid)

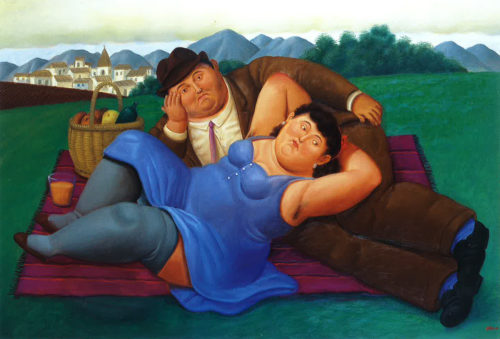

Fernando Botero

“Thus the Oedipus complex is not a hidden “meaning,” which would be lacking only in consciousness or speech. The Oedipus complex is not a structure buried in the past that can always be restructured or transcended by “reactivating its meaning”; the Oedipus complex is the dramatic structure, the “theatrical machine,” imposed by the Law of Culture… ”

Louis Althusser (Writings on Psychoanalysis)

Althusser wrote his essay on Lacan during a period of extreme stress (following the suicide of his friend Jacques Martin). It must be approached in a sense, like one approaches Artaud. And yet, because of the anxious and almost violent emotions of Althusser’s style, it feels oddly appropriate for the material. For there is no really rational approach to Lacan.

“Alfred Hitchcock directed murder scenes like love scenes, and love scenes like murder scenes. In each of his films, with ferocious skill, the master of suspense places the viewer in a troubling situation, sometimes making him the author of a crime of which he is no more than the virtual witness, sometimes the central character in a carnal relationship in which, by definition, she can never participate. As for Hitchcock’s heroes, whether killers or victims, Prince Charmings or Cinderellas, spies or assassins, they are always prey to a sort of logic of surrender to impulse that makes them strangers to themselves and strips them of any psychological consistency. A filmmaker of the unconscious, of repression and fetishism, Hitchcock filmed dreams as reality and desire as perversion: between the sublime and the abject.”

Elisabeth Roudinesco (Philosophy in Turbulent Times)

Roudinesco writes the above as an introduction to her chapter on Althusser. Althusser had murdered his wife (Hélène Rytmann) by strangulation. It was determined Althusser suffered from manic depressive psychosis, and a deep ongoing pathological melancholia. It was that strange uncanny conjunction in life, or some lives, between history and the dislocation of history, or an anti-history. Hitchcock is suggesting all crimes are love stories. Adorno even said every work of art is an uncommitted crime. Lacan’s own obsessive fixations on the Oedipus complex in Freudian theory was itself costly, personally, for him. Althusser could not escape his own allegory. There was great outcries of privilege when Althusser was sent to a hospital, and never had to spend a moment in a police station.

“In reality this populist and revanchist discourse, anti-elitist and anti-intellectual—which was springing up everywhere at this time and has continued to grow in volume ever since signified that in the eyes of a section of public opinion dominated by hatred of defiant consciences, the murder committed by Althusser had to be merely the visible part of a much more dreadful crime: the one perpetrated for decades by all the communists in every country in the world…”

Elisabeth Roudinesco (Ibid)

Fernando de Szyszlo

Yes, this is another digression, but then maybe it’s not. In the contemporary cultural landscape, a screen saturated society now sits and feels nostalgic for the last two years of lockdown. Zoom nostalgia. A report, or reports, have come out noting how much more psychological damage has been caused to children in Norway and Denmark, due to school lockdowns, compared to Sweden, which had no school closures. No mention is made in these reports about the climate of fear, of hysteria, and the message to children as they watched adults, masked, scurry around furtively. There are only statistics regarding lost playtime, and remote learning. Both no doubt harmful. But nothing of the message to children that people are unclean. That they, perhaps, are also unclean. That they may hurt their grandmother. They may hurt each other. There is nothing on the implications of obsessive hand washing. Only mild surprise at the dramatic upticks in ADHD in adolescents.

“Humanity inscribes only its official deaths on its war memorials, those who managed to die on time, that is, late, men in human wars, in which only human wolves and gods sacrifice and tear each other apart. Psychoanalysis, in its sole survivors, is concerned with a different struggle, in the sole war without memoirs or memorials, which humanity pretends never to have fought, the one it thinks it has always won in advance, quite simply because its very existence is a function of having survived it, of living and giving birth to itself as culture within human culture. This is a war that, at every instant, is waged in each of its offspring, who, projected, deformed, rejected, each for himself, in solitude and against death, have to undertake the long forced march that turns mammalian larvae into human children, that is, subjects.”

Louis Althusser (Ibid)

To donate to this blog and to the Aesthetic Resistance podcasts, use the paypal button at the top.

“The instinctual desire for a lost or missing story. The search must become more frantic.”

This, in the context of a world without oxygen, “life” on a moonscape inhabited by those without instinct, without desire, who find nothing lost or missing, searching for nothing. It shocks the soul.

Great post. Somehow you’ve managed to tease something out of what has been a

major conundrum to me for a number of years. Thanks.