Rhondal McKinney, photography.

“In order to further explain and/or defend our description, we in turn develop a story about what we believe is true. There is nothing wrong with storytelling. In fact, it is a very effective way of transferring ideas. If you stop and think, the way we communicate with each other is basically through a series of stories. Stories are open-ended and metaphorical rather than determinate.”

Ludwig Wittgenstein (Tractatus)

“Death is the mother of beauty; hence from her, / Alone, shall come fulfillment to our dreams / And our desires.”

Wallace Stevens (Sunday Morning)

“European civilization is approaching the term of its existence…”

Erich Auerbach (postscript to Mimesis)

“There is no thing that with a twist of the imagination cannot be something else.”

William Carlos Williams (Kora In Hell: Improvisations Xxvii)

“Earth but a player’s stage.

Mount we to the sky;

I am sick, I must die—

Lord, have mercy upon us.”

Thomas Nashe (In Time of Pestilence)

There is a universe. So there seems something refractory, or perverse even, in asking why there isn’t.

I watched a series of youtube conversations under the umbrella title of “Why is there Something, and not Nothing?”. Mostly it was physicists, and cosmologists. And while it was interesting, the answers were remarkably unsatisfying. And I think the most telling reveal was that not a single guest mentioned ‘death’.

But first, there is a problem with language here, and with logic. Asking *why* is there is something and not nothing is like asking why is water wet? The answer is water IS wetness. Wetness is water (or fluids I suppose). You could describe the qualities of wetness. But the question is meaningless. Why is there is something and not nothing is also, finally, a meaningless question. There IS something. Why isn’t there something else or something different is a meaningful question. Sort of, anyway. The second problem, after the word *why* is the word *is*. What does that mean here?

I think that the reason the idea of the universe ending ( a different question), or even our galaxy ending, in a trillion years, so disturbs us is because that ending is the story of our own death. Our death is the end of the universe, too. Of our universe. The absence of consciousness is our own personal *Heat Death* (of Big Freeze). Of course there are other aspects to contemplating cosmic endings, though all of them carry a personal quality. Contemporary culture is deeply attached to the idea of purpose. And if all of humankind’s achievements disappear, there cannot be a purpose to any of it. Humans can look back at thousands of years of achievements (however one wants to evaluate that) and then to have to think of it disappearing, erased, thrown into the void, well, it IS unsettling. But still, the fear and trembling attached to our Sun slowly dying, after first, apparently expanding and swallowing all the closest planets, is terrifying (we would all be dead, I’m told, long before that, because of cold…but never mind). But my point is that this is all, at the most bedrock core stone basement of cognition, about our own mortality. The finitude of our existence. All cosmology is allegory, even that of contemporary physicists.

Metropolis (dr. Fritz Lang, 1927)

And so I want to write more on the nature of allegory. For I have to come to see this as perhaps the most profound of ideas in human history. And it also explains the lasting import of literature and narrative.

“The provision of accommodations between Greek and Hebrew thought is an old story, and a story of concord-fictions—necessary, as Berdyaev says, because to the Greeks the world was a cosmos, but to the Hebrews a history. But this is too enormous a tract in the history of ideas for me to wander in. I shall make do with my single illustration, and speak of what happened in the thirteenth century when Christian philosophers grappled with the view of the Aristotelians that nothing can come of nothing—ex nihilo nihil fit—so that the world must be thought to be eternal.”

Frank Kermode (The Sense of an Ending)

Now, in the Bible, as we know, the world is created out of nothing. Aristotle came along to suggest it was eternal. And in the 13th century there came a sort of intellectual and religious conflict around just this point. It led, as Kermode put it, to a double-truth. Philosophers did remarkable and intricate thinking in pursuit of a truth they would be forced to deny. Now much earlier St Augustine came up with ‘formless matter’, a sort of compromise. It was somewhere between matter and nothing. It was potentiality (rather like string theory, actually). But still, the arrival of Aristotle changed human thinking about eternity.

Botticelli (St Augustine, 1480)

Frank Kermode (Ibid)

Angels presented a certain theoretical problem, too. St. Thomas came up with a solution.

“His angels, though immutable as to substance, are capable of change by acts of will and intellect. So they are separated from the corporeal creation, which is characterized by a distinction between matter and form, and also from God. They are therefore neither eternal nor of time.”

Frank Kermode (Ibid)

What is relevant here is that Thomas’ solution (embraced by Milton) introduced the idea of ‘time’ to the discourse around origins. The concept of aevum was another register of time seperate, but participating in both eternity and time (man’s mortal time). Now this is actually rather significant.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, photography.

“Aevum, you might say, is the time-order of novels. Characters in novels are independent of time and succession, but may and usually do seem to operate in time and succession; the aevum co-exists with temporal events at the moment of occurrence, being, it was said, like a stick in a river. Brabant believed that Bergson inherited the notion through Spinoza’s duratio, and if this is so there is an historical link between the aevum and Proust; furthermore this duree reelle is, I think, the real sense of modern ‘spatial form,’ which is a figure for the aevum.”

Frank Kermode (Ibid)

This concept, this aevum, migrated, as it were, to the political and legal realms. Kings never die, for example. They never die because, like Angels, their crown exists in Aevum, it is participating in eternity. The mortal body may die, but the King’s second body lives on. This was to be a very influential and useful idea for royalty, and for others, actually. Rome never dies, etc. The King is dead, long live the King. If the world, as Kermode says, was not eternal (as many suggested) man still retained a kind of immortality or perpetuity through the aevum.

“The Empire, the People, the legal corporation, the king would never die, because each was *persona mystica*, a single person in perpetuity; and the entire cycle of created life, with its perpetuation of specific forms, had the same kind of eternity within a non-eternal world. The old Platonic distinction between athanasia and aei einai, deathlessness and being-for-ever, was given a new fictive shape; men can have the first, but not the second, truly eternal, quality.”

Frank Kermode (Ibid)

This 13th century debate echos today. Not that anyone discusses angels much, but the Western viewpoint on our bodily mortality — and much else, was shaped by Thomas, Averroes and Aristotle. And, per Kermode, it is reflected again and again in narrative art. King Lear is a perfect example. So is Spencer and Milton. And Tragedy, as Kermode notes, is the offspring of apocalypse. There is also something accommodating prophecy in all this. Religion in general finds prophetic announcements quite useful. The idea of time that most people today accept is born of the angelic debates. All plots are second generation dupes, as it were, of prophecy. From Donne to Raymond Chandler this remains true.

So, today’s cosmologists and physicists have internalized these ideas, too. They are not immune to the forces of history, although one of the fictions they seem to like to perpetuate is that they are in fact sort of a high priest class of oracle. And of course they do traffic in a private esoteric language, that of math primarily, and yet, when one breaks down the pronouncements, the are still creating plots.

Guido Reni (Archangel Michael, 1635)

Two things are worth noting in all this. First, regards quantum theory. The new hot emergent market of quantum computing is just snake oil. A particular brand of snake oil, however. First, quantum computing requires enormous, ENORMOUS, GINORMOUS, GARGANTUAN machinery — in particular cooling machinery. The cost for these massive physical plants that would cool Google or Microsoft’s quantum computer are such staggering energy drains that the mind boggles. Second, there is this problem with rapid (as in nano-seconds) deterioration of qubits — the quantum version of bits. There is, as Sabine Hossenfelder, a German physicist, observed, a huge quantum computer bubble out there. One about to burst. And this segues into the problem (or one of the problems) with quantum theory.

The questions surrounding quantum physics is that General Relativity is 100 years old. And the standard theory of particle physics was completed fifty years ago. There has been nothing new since then. And there is little in the way of even a signpost to a unifying law beneath both.

But then I am not a physicist. I will only add that the problem of dark matter (which sounds suspiciously like St Augustine) is that there are simply too many anomalies in the observation of galaxies (to name one problem) to really explain dark matter. There are multiple alternative theories and it’s beyond my expertise to evaluate any of them. But the measurement question remains and will probably always remain an issue for quantum mechanics. Sean Carroll, who is the successor to Feynman at Cal Tech, has said its embarrassing to have no explanatory theory for quantum mechanics. There is only math that works. Meaning the results of certain experiments can be accurately predicted.

Roger Humbert (photography)

Also, just my distrust of technology, I guess, but the technology of galactic measurement has to be questioned at some point. Math may add up but that isn’t the issue. The issue is trusting the *observation* which is also via technology (more on that below). In the end nobody knows what is out there.

And, there is little chance, I don’t think, that mathematics or physics ever escape the fact that the individual, at least European and North American, since the 12th century say, are part of a world view not independent of their equations.

“I would never have gone beyond the intention of an author { } either in his consciousness, or in his unconsciousness.”

William Empson (Using Biography)

Now, Michael Wood quotes the above remarks by Empson as a kind of indicator of just how far afield Empson had gone. Somewhere between (per Wood) Monty Python and delusional. Or theological.

But the issue of knowing an author’s intention, or artist, whether playwright or painter or composer is a curious topic. One does not ask the intention of Schrödinger, say, when he came up with the cat in the box. Why a cat? But science is impersonal. Math is purely impersonal. Allegedly. I am not at all sure it is, but regardless the intentions of a Paul Dirac or, today, a Roger Penrose, are irrelevant. The assumption is the intentions of the scientist remain the same, a search for the truth of the material world. Or, the truth of the ‘world’. And this assumption is key, I think, to understanding the supposed (or real) crisis in quantum theory. It also raises the question of what exactly does *truth* mean in this context?

“Detective fiction originates at the same time as the trusts, the big banks, and monopolies: mechanisms that make wealth impersonal and separate capital and capitalist. The victim, on the other hand, is still attached to his small capital, like the criminal who covets it. They are betrayed by economic independence. Detective fiction enacts the antithesis between life and property and between life and individuality to have one, it is necessary to give up the other.”

Franco Moretti (Signs Taken for Wonders)

Moretti is writing about Arthur Conan Doyle primarily, and Agatha Christie. Important to keep this in mind, but more on that below.

Rene Magritte

General Relativity began only slightly later than Detective fiction. It began, as has been noted before, at the end of the 19th century and coincided with optical inventions that allowed ‘us’ to see (!) a previously unseen world. Germs and microbes and later atoms and electrons. The detective novel is, as Moretti notes, anti-novelistic. The characters do not develop. It is more akin to the short story. And the criminal, the guilty, is not isolated because of his guilt, but is guilty because of his isolation. And here Freud’s *death instinct* is important because that urge toward stasis is a dialectic within modern capitalism, notwithstanding the propaganda to the contrary.

“…detective fiction’s object is to return to the beginning. The individual initiates the narration not because he lives – but because he dies. Detective fiction is rooted in a sacrificial rite. For the stereotypes to live, the individual must die, and then die a second time in the guise of the criminal.”

Franco Moretti (Ibid)

There is a compulsive repetitive quality to detective fiction, and as Moretti notes, it’s success is in the fact that it teaches nothing. Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment is not detective fiction. It is almost the antithesis. Raskolnikov has to confess. He solves his crime himself. Now Moretti here also points out what he calls a deep enduring trend in contemporary man, the desire to sink into the environment, rather than playing an active part in it. But what he means is not that humans do not want to control Nature, at least most, to some degree, but that they seek that inertia or stasis which is also modern conformity. Contemporary humans tend not to want to make waves.

“This reflects a new relationship with legal punishment: in the middle of the nineteenth century, the focus of attention shifts from execution to the trial. While the former underlines the individual’s weakness by destroying his body, trials exalt individuality: they condemn it precisely because they have demonstrated its deadly greatness. The criminal is the person who always acts consciously. On this premiss, detective fiction detaches prose narration from historiography and relates it to the world of Law…”

Franco Moretti (Ibid)

Ian Fisher

Allow me one more quote here from Moretti:

“Detective fiction separates individuality and bourgeoisie. The bourgeoisie is no longer the champion of risk, novelty, and imbalance, but of prudence, conservation, and stasis. The economic ideology of detective fiction rests entirely upon the idea that supply and demand tend quite naturally towards a perfect balance. Suspicion often originates from a violation of the law of exchange between equivalent values: anyone who pays more than a market price or accepts a low salary can only be spurred by criminal motives.”

Franco Moretti (Ibid)

Today I would argue this is even more true. Even as bourgeois economics loses its legitimacy. And certainly bourgeois institutions lose legitimacy. The lost legitimacy in ‘the Law’ is a critical factor in the anxiety that pervades the West today. And to link this, again, science today is the science of the bourgeoisie. And while the bulk of scientific activity is in the banal corporate for profit realm, even quantum theory — which sees itself as a rarified sect of the elect, is still bound to capitalism. (Hence quantum computing, which is largely a new mythology ). And if money is nearly always the motive for crime in detective fiction, then Moretti notes it is interesting that production is always innocent. And this mirrors, or is partly the cause, of the popular tendency to blame poverty on the poor. Or blame steroid abuse on athletes and not on Eli Lily.

Now detective fiction soon became crime fiction, and TV franchises were detective (or cop shows) stories that largely replicated the original genre form. And always, the crime fighter, or detective, is there to buttress the status quo. And this repetitive short hand erases the past, the painful memories (even if sometimes only collective) of western societies still recovering, or not, from Colonial crimes and dwindling dividends from former extractive projects. Of course today, wealth has been transferred to the top 1% and we are currently undergoing a massive economic restructuring. The climate crisis is being employed as a meta-narrative to instill guilt in the bourgeoisie as well as the underclass. And the solution, or better, the cure, resides in the expertise of the ruling class. If Climate Change is a clock put on a detective novel that is environmental crisis, then the Doctor/Detective is now a class. The culture as a whole lives on adumbrated narratives that reproduce the ideology of the 1%. The ruling class is the special saviour of the status quo. Look at Bill Gates. No medical training, no real training of any kind, actually, but he is an avatar for wisdom. And those figures like Gates or Attenborough or King Charles appear as if out of kindergarten story book. Fauci, too. They are as a group stunningly inarticulate, and seen as a bit bumbling and awkward, full of false modesty and avuncular advice. But they fit into this new narrative that validates the society overall as infantile. And this is part of the regression that has taken place over the last 100 years.

Al Held

” Since Poe, the detective has incarnated a scientific ideal: the detective discovers the causal links between events: to unravel the mystery is to trace Them back to a law. The point is that – at the tum of the century – high bourgeois culture wavers in its conviction that it is possible to set the functioning of society into the framework of scientific – that is, objective – laws. “

Franco Moretti (Ibid)

One thing is important in this: these detective or crime stories (Doyle, Christie, et al) make the relationship between science (and technology) and society unproblematic (Moretti). The criminal is simply a criminal, at least in earlier incarnations of the form. The cause or deeper motives of the criminal are not really investigated. Today this is not at all true. The motives of the criminal (see Criminal Minds, for one, or Silence of the Lambs) are of exaggerated importance, actually. But the explanation always absolves society. The system is not to blame. The criminal may even be seen as a victim of society. But he or she is the exception that must be reincorporated back into the well oiled machinery of the system. The sacrificial victim, again. The authority has to expect aberrations and it is there duty to understand and ‘fix’ the problem, protect society and even feel sympathy for the criminal. But this is the sympathy that gently reassuringly pats your hand as they wheel you in for a frontal lobotomy or electro-shock.

The quantum physicist is a cosmological detective. A scientific Sherlock, not a scientific Marlow. And pysicists are the high priests among scientists. They are the ones who don’t need results, per se. They barely need theory. They write stuff nearly nobody understands. And much of it, as Sean Carroll admits, NOBODY DOES understand. (as a side bar, its surprising that the Everett Interpretation of quantum physics took so long, since it’s actually rather obvious…no?). The physicist wants to solve the mystery, like the detective. The detective, in its original form, didn’t care about arrest or the Law. The physicist doesn’t care if his solved mystery goes anywhere, leads to anything, at least at the moment. It was Umberto Eco who said vis a vis detective fiction that clues are more like symptoms. This is in keeping with the idea of a society that must be kept healthy. And it reinforces again, as if this needed more reminders, that sacrificial rituals and allegory are the foundations of society.

Jacqueline Hassink , photography. (Boardroom series)

“And Holmes is just that: the great doctor of the late Victorians, who convinces them that society is still a great organism: a unitary and knowable body. His ‘science’ is none other than the ideology of this organism: it celebrates its triumph by instantaneously connecting work and exterior appearances (body, clothing): in reinstating an idea of status society that is externalized, traditionalist, and easily controllable. In effect, Holmes embodies science as ideological common sense, ‘common sense systematized’. “

Franco Moretti (Ibid)

Now it is interesting that Moretti wrote this in 1983. And was writing primarily about British locked room mysteries, or about Sherlock Holmes. And this date, 1983, was close to the cusp of another incarnation of detective/crime fiction. Or perhaps it more marked the end of an era of the independent anti-hero detective, the PI, the man with a code of honor. A figure exclusively American. This figure was being replaced with Dirty Harry (1971). The post Vietnam syndrome was anticipated by the urban vigilante. But this was in keeping with something else at that time. The shift back, or regression (at least partly) toward fascism. But it is important to note, too, that one can assume Moretti never read Chandler or Hammett. Or even crime stuff that came out of Black Mask; Cornell Woolrich and Jim Thompson, et al. For even in the 1930s Hammett was critiquing the genre through his writing within the genre. It’s also likely that this is a double reality; both regressive and progressive (as Marx liked to say). The official literature of the MFA programs, starting with the Iowa writers workshop (replete with some CIA involvement) began a trend of banalizing the novel. And literature in general. The same happened to poetry. But in the U.S. This becomes a complicated discussion, but it is worth remembering, I think, that the best of Chandler is as good as anything written in this period. And other writers, Patricia Highsmith comes to mind, was working off genre forms while transcending them, and traces of the detective genre crop up in everyone from Paul Bowles to Hemingway. The ossified class hierarchy in England is simply going to manufacture a different sort of fetishization. Its capitalist but its not the same. America had immigrants, the enigma of arrival. And it continued to absorb them through the 40s. I cannot see a Delmore Schwartz in the UK or a Bly for that matter. Or Wallace Stevens. There has always been for me (this is a side bar) a love hate thing with Eastern educated white poets (in particular). Stevens, Crane, Schwartz, Berryman, and Lowell (no doubt the best of that particular group). While Bly and James Wright were both a part of that, they were also outside of it. (Alan Tate denied Wright tenure at the University of Minnesota, out of petty resentments, and likely the fact Wright was the far better poet and a friend of Bly). But it’s all that whiteness, all the east coastness (and all that Harvard literary sangfroid).

But the fetishizing of authority that runs in and out of, at least, American writing (and mostly in all English language fiction of this era) was a concealed valentine to fascism. Again, not true of the best novels of Faulkner or Hemingway or even O’Connor, but it was there is mass culture from the end of WW2. And it was there is other ways (Stevens stayed too long an admirer of Mussolini).

Ken Lawrence has an excellent essay at Covert Action magazine this month;

and while I do not agree with all of it, he quotes a remarkable passage from Alfred Sohn-Rethel:

“It is clear, therefore, that enterprises of this new modern type which are run on the principle of structural socialization of labor but continue along private capitalist lines, are under continual coercion to produce. So long as they are not totally closed down, thrown on the scrapheap, so to speak, they must produce regardless of whether there is a demand for their products or not. And if there is no demand of a real kind, that is, of reproductive values, then an alternative demand, that of non-reproductive values, must be created in order to keep the world in motion. Non-reproductive values are products which are not consumed either directly or indirectly into the maintenance or renewal of human labor power and social life or into the renewal of productive machinery. Among these, armaments obviously have pride of place, and in our most recent experience since the 1960s onwards can be added the manufacture of waste products and space exploration. In order to make the demands effective a state power is needed to compel the population to pay for this production.”

Alfred Sohn-Rethel (Economy and Class Structure of German Fascism, 1978)

James Fee, photography.

Moretti wrote ‘mass culture is the culture of unawareness’. I think what has transpired in the last forty years or so is the merging of mass culture and politics, and of political commentary. In other words, political fables. It has been the making of politics into something unserious. Reagan was the inaugural storyline, here. But with Bush Jr and Trump and now Biden the empire is spiraling into new dynamics of storytelling. And, more significantly, the Covid fable and now the latest installment of the Climate sub plot (along with the WEF and the Great Reset) these new dynamics require a deeper reading. For they are, partly at least, stages along the road to the destruction of reason.

“The process of concealment of detective fiction’s deep meaning is also the process of manifestation of its surface meaning. This two-sided process, enmeshed in the specific literary structure of detective fiction, presents an extraordinary analogy with the mechanism of capitalist production as Marx, in one of his many descriptions of ideology, describes it…{ } Commenting on this and other analogous passages, Nikolas Rose has observed how Marx discusses ‘two realities and the distance between them. For the phenomenal forms are not illusory appearances, they are realities. They are the form of the reality which capitalist relations of production produce, a reality which is simultaneously the form of manifestation of these relations and the form of their concealment.”

Franco Moretti (Ibid)

That double reality…and a few paragraphs later…

“All of mass culture’s great symbols and formal procedures emerge in precisely the same way. There is a cultural process which – through its deep structures — generates surface laws and symbols which then autonomously rescind the link with their roots. The deep and confused effect they universally provoke – the vampire as the vamp, suspense as the chase – depends precisely on the fact that basic cultural values are both present and missing, active and unrecognizable, in them. Mass culture is, in this way, a full- fledged example of cultural fetishism.”

Franco Moretti (Ibid)

Julião Sarmento

In the digital age, this is accelerated. The production of meanings which the producers of ideology probably don’t entirely intend, but also don’t care. When the transference of wealth is this close to completion, they are probably correct not to care. The detective/cop narrative serves as a kind of (per Moretti) *night watchman* for bourgeois society.

“But on the other hand, detective fiction is liberalism’s executioner, in aIl its fundamental meanings and especially because it promulgates a culture that is already a closed and self-referential system.”

Franco Moretti (Ibid)

One could extend Moretti’s observations here to Marvel Comics and Hollywood product today, overall. A closed system of self referential authoritarian cartoon stories. Also the idea of rescinding the link to the past is an important insight. To understand the structural dynamics for what is, essentially, capitalist ideology it seems, to me anyway, is important because mostly it is never talked about. And it is never talked about because it functions, this dynamic, as concealment. That is what much of mass culture does. It erases the past. And yet, and yet…I have said before that all stories are crime stories. And all stories are about exile and a homesickness. I think the problem is that Conan Doyle, and Agatha Christie and Ellery Queen even, are exactly what Moretti is thinking of, while something else, a uniquely American form, was emerging. American culture in general was, until the watershed 70s, invigorated with working class voices, black and Latin American emigres, much as the Jewish refugees that fled Hitler created a sub-genre of cinema after the war. The recipe for fetishized narrative and mass culture was recuperated after the 70s, really. It began after WW2 certainly but mass culture, in the form of Hollywood and in particular television, returned to the compulsive curative of repetitive self enclosed worlds. In a sense, the recuperation of the closed box narrative (not just the mystery) was expressed in network TV drama. In particular in cop shows.

Helena van der Kraan, photography.

“Faye is tracking the oscillation whereby, in 1987-1988, it became possible for Derrida, Lyotard, Lacoue-Labarthe, and others, to say, in effect: Heidegger, the Nazi “as a detail,” by his unmasking of the nihilistic “metaphysics of the subject” responsible for Nazism, was in effect the real anti-Nazi, whereas all those who, in 1933-1945 (or, by extension, today) opposed and continue to oppose fascism, racism, and antisemitism from some humanistic conviction, whether liberal or socialist, referring ultimately to the “metaphysics of the subject”-such people were and are in effect “complicit” with fascism. Thus the calls for an “inhuman” thought.”

Those who in 1933 -1945 called out Heidegger included Adorno, Karl Löwith, and Ernst Bloch, as well as Gunther Anders. My point is not to debate the work of de Man, or of Heidegger really, but rather the emerging cottage industry of ‘anti-French theory’. This is what I mean by intellectual fashions. Because what I take away from an awful lot of this stuff, or certainly the effect of it, is to justify a certain anti-intellectualism (see Moretti on Sherlock Holmes). There is more blame placed on Derrida, and by extension on Lyotard and Baudrillard, than on Heidegger. At least in the U.S., where hating the French comes very naturally it seems. I am not someone who can ever be accused of being a fan of French post structuralists. But I think I dislike even more the all too easy sniping at this stuff (Suzanne Gordon calls it incomprehensible). Well, no, its not. And some of it is very good, in fact. If you want to vent against Derrida, fine, but do it cogently. Not as snarky hipster faux leftism (see Jacobin).

Jules Olitski

There is a very good take on Heidegger from Thomas Riggens;

“How did Heidegger and others, “of such stature”, let themselves “become enmeshed in the politics of the inhuman? A preliminary answer may be that people really don’t understand the latent Nazism in Heidegger’s thought so his “stature” is undeserved. Also, maybe Nazism is not as “inhuman” as we like to think. It is rather one of the possible outcomes of capitalism under stress. The attempted extermination of the Native Americans, slavery, the holocaust, Vietnam, Apartheid, the Taliban’s, and others, treatment of women, the ethnic cleansing of Palestine were all done and are being done by humans–not just by Nazis. The problem is humans motivated by racism and/or greed for the lands and wealth of others due to an economic system predicated on profit and financial conquest. To understand Sein und Zeit we must first understand Das Kapital. Only in the socialist future, when we are fully human, will we understand what was “inhuman” in our past.”

Thomas Riggens (The Nazis Among Us: Heidegger and the Hideous)

Now, after all this stuff about the pretensions and problems with contemporary science, I wanted to add a quote from Sean Carroll. It is a very simple paragraph, in a sense, but it’s true. Carroll was asked during a radio interview….at the end….’But why should anybody care?’ This was in reference to the Higgs Boson.

“The answer I came up with still makes sense to me: “When you’re six years old, everyone asks these questions. Why is the sky blue? Why do things fall down? Why are some things hot and others cold? How does it all work?” We don’t have to learn how to become interested in science—children are natural scientists. That innate curiosity is beaten out of us by years of schooling and the pressures of real life. We start caring about how to get a job, meet someone special, raise our own kids. We stop asking how the world works, and start asking how we can make it work for us. Later I found studies showing that kids love science up until the ages of ten to fourteen years old.”

Sean Carroll (The Particle at the End of the Universe)

Vincent Desiderio

I believe Carroll. But there remain problems. The Large Hadron Collider cost nearly 5 billion dollars. As I noted before much of that money came from the U.S. government. Operating costs run around a billion a year. A half dozen European countries also contributed substantial amounts of funding. Not to mention that since the NATO/Russia proxy war CERN has decided to sever ties with both Russia and Belarus. So it’s not quite as innocent as Carroll wants us to believe.

and https://bigthink.com/hard-science/large-hadron-collider-economics/

“Indisputably the Father can never have begotten a being who was begotten from eternity. What was made from eternity, was never in the process of being made. Any being whom the Father begot from eternity, he must still be begetting, for an action which has no beginning can have no end. “

John Milton (De Doctrina Christiana)

It’s probably not an accident that the Higgs Boson is called ‘the God Particle’.

“ The essence of the Oedipal complex is the project of becoming God—in Spinoza’s formula, causa sui.… By the same token, it plainly exhibits infantile narcissism perverted by the flight from death….”

Norman O. Brown (Life Against Death)

I think infantile narcissism is a pretty interesting idea. At least regards consciousness. The development of the psyche. I do sort of argue for something I would call quantum epistemology. I think cosmologists and quantum physicists tend to downplay the interpretative aspect of what they do. And if you look at Jainism, for example, you find realms in the Universe. And the soul is eternal and the Universe is eternal. But multiple realms, which feels very much more subjective and intuitive than a an Everettian multiple worlds theory, would even sort of explain panpsychism. My point is only that each quantum theoretical idea has a hidden poetic or allegorical side to it that seems to remain hidden.

Michael Eastman, photography.

Let me end with a discussion of another very costly bit of cosmological technology; The James Webb Space Telescope, which is using up about half the allotted astrophysics budget of the US govt. Around ten billion dollars.

“From the outset, an important thing to realize about the James Webb Space Telescope is that it is not really a telescope. In fact, the giant contraptions that today “observe” the outer galaxies do not observe in any optical sense, as they do not photograph the universe directly. Rather, these experimental devices are designed to produce data based on preset detection variables and field delimitations, data that can be reconstructed into advanced imagery. Insofar as the JWST can be called a telescope, it is only as an analogy to the classical instruments that first opened human eyes to the distant universe. The images it creates are fundamentally shaped by pre programmed search criteria and theoretical parameters, on the basis of complicated predictions derived from the theoretical framework itself.”

Bjørn Ekeberg (Metaphysical Experiments)

And here we run into one of the basic problems I have with contemporary science. Whether climate or cosmology. The reality being described is relational. It’s not actual. Particle physics deals with things too small to see with the naked eye, but also too small to see period. The instruments used don’t actually *see* things, they surmise they are there because math tells them it must be so, and in other instances with different experiments, the same results were achieved. Simply put, in particle physics, the experiment creates that which is found. Which is sometimes only a probability.

Needless to say the myth of science as disinterested is exactly that, a myth. Things such as the LHC require enormous funding which does not just drop from the sky. Physicists must promote a certain idea, generated interest, market and spin and, nearly always, involve the US government. Nothing is funded to the tune of ten billion dollars that does not have Pentagon interest.

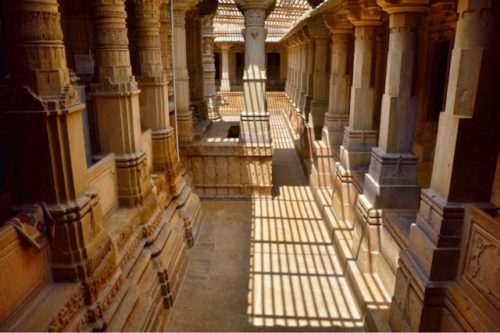

Jain Temple, Jaisalmer, India. 12th century.

“A true diagnosis, in the Nietzschean sense, must have the power of a performative. It cannot be commentary, exteriority, but must risk assuming an inventive position that brings into existence, and makes perceptible, the passions and actions associated with the becomings it evokes.”

Isabelle Stengers (Cosmopolitics 1)

This is not unlike Tragedy. The process of revealing is also the bringing into existence. This is the paradox of tragic drama.

The Jain mendicant does not see the world from a position of identity. Jainism does not see the world made up of things separated, and with their own identity. Capitalism does that. Property is the foundation of such thinking. Science became something else with mass computation. The era of digitalization has allowed for (what Ekberg calls) a new metaphysics in science (except physicists would deny that, and DO deny it). And computation at the levels of the James Webb Telescope (sic) or the LHC, can only be done through government channels. Everything the Empire (the US) touches is tainted. That tendency I spoke of regards fascism can be traced back long before The Third Reich. The Reich was only a symptom, a critical one, but still a symptom, of the emotional and intellectual gangrene that infects the contemporary world.

I leave off with an article from 2014 by Stuart Jeffries. I have no reason for so doing other than I liked it.

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/oct/22/jean-paul-sartre-refuses-nobel-prize-literature-50-years-books

To donate to this blog and the Aesthetic Resistance podcasts, use the paypal button at the top of the page.

Surfing in the eternal ring, or

https://www.counterpunch.org/2023/01/13/playing-god-wisdom-from-the-greeks-or-monsters-of-artificial-intelligence/

A La recherche des temps perdue many times again:

I gravitated towards what is now labeled STEM out

of repulsion to my Intro to Drama professor who was

equally repelled by me & gave me a D-. I liked Antigone

& King Lear &, amidst his tiresome comments about Tragedy, I

kept bringing F N & the Birth of Tragedy & how my life as a

young short-order cook sucked so far, except for

week-emds woth motorcycle goddess Dorothea, a fellow

student who financed her studies by dabbling in the oldest

proffession beyond other transgressions.

Soon enough, I was suspended & started working in

Miami Beach maintenance enginner gigs where I learned

about motors & valves but read much of the likrs of

Joan Didion, Brecht & Hess. Eventually steppenwolfed

a way to a more disciplined & committed life. My current

interest in theatre is limited to Netflix since I don’t travel

much anymore. Maybe, I hope, there’s a lesson or hint

for similar travelers.

Tremendous