Anonymous (Kurkulla, Central Tibet 1500 BC)

“I believe that the action in film must become—will become—more and more interior.”

Robert Bresson (Ideas and Men,Radio-télévision française, 1950)

“On average, it took 58 days for the president to sign off on a target, one slide indicates. At that point, U.S. forces had 60 days to carry out the strike. The documents include two case studies that are partially based on information detailed on baseball cards. The system for creating baseball cards and targeting packages, according to the source, depends largely on intelligence intercepts and a multi-layered system of fallible, human interpretation. “It isn’t a surefire method,” he said. “You’re relying on the fact that you do have all these very powerful machines, capable of collecting extraordinary amounts of data and information,” which can lead personnel involved in targeted killings to believe they have “godlike powers.”

Jeremy Scahill (The Drone Papers)

“What the bourgeoisie therefore produces, above all, are its own grave-diggers.”

Marx and Engels (The Communist Manifesto)

There is a haunting and brilliant essay by T.J.Clark on Velasquez in the September London Review of Books. I have thought about it a good deal since I read it a few weeks back. Then the other day I watched Paul Schrader’s The Card Counter. It’s his best film in a long time, and maybe ever. And in some strange way these two experiences are intertwined. Clark focuses particularly on two portraits of Velasquez, Mars Resting, and Aesop. I have always been struck with the Mars painting ( both painted for Phillip IV for his hunting lodge Torre de la Parada). Firstly, it feels very contemporary. But I had not looked very carefully at the Aesop portrait before. Or, the third painting in this group, or related anyway, The Jester Named Don Juan of Austria (1633). In some ways, the painting of the court jester is the most peculiar and disturbing. But I think the Mars portrait is rightly the most famous and likely the most profound.

“…for the moment I want to focus on the quality of the two figures’ expressions.‘Expression’ is a troublesome word. Neuroscientists have accustomed us to the notion that the brain may have a specific circuitry or ‘module’ devoted to reading other people’s faces and inferring from them things as intangible as feelings, intentions, states of mind. Some say this ability (or the confidence that one has it) is part of what went to make Homo sapiens. But the confidence I put in parenthesis is easily lost. Inference as to internal states is difficult – the way it’s done is a mystery – and mistakes can be fatal, especially in a group of hunter-gatherers still working on bonds and allegiances. Who was the first human being to see the inferring of mental states as a distinct activity, and cast doubt on its premises?”

T. J. Clark (Masters and Fools, LRB, Sept 2021)

And here, precisely, is why this essay is so relevant. And perhaps why The Card Counter so haunts one. For this current class assault on the poor and working class by global NGOs, the WEF, the global financial system, and those unelected billionaires and media moguls who now virtually dictate policy (only ten or fifteen years ago people would wax outraged at the Koch Brothers and their influence, with good reason. But the reach of asset management firms like Blackrock or Vanguard, and NGOs such at the Gates Foundation, far outstrip the Koch’s) — that part of the policy they dictate, part of the agenda, it seems, is to coerce an absolute kind of obedience, and simultaneously to strip the qualities of humanness from us.

Hendrick ter Brugghen (Heraclitus, 1628)

In all three of the Velasquez portraits under discussion the expression of the subject defies simple description. I think this is especially true of Mars.

“My subject is the quality of a certain look in Velázquez – a certain expression. I am not saying that Aesop, Mars and Don Juan of Austria exactly share it, or that it is exclusive to them, but I think their looks are comparable. Distance – keeping the viewer at arm’s length with one’s eyes, questioning, maybe concealing something – seems to be in play in all three. The look in point doesn’t puncture the illusion, exactly (though Lepanto on the wall may), but in some sense intercepts it. The look may be interested in itself: mirrors are everywhere in Velázquez’s world. Maybe the look is even asking itself what a look – a look out of the picture, over the footlights – does to the bargain on which any picturing rests. That bargain is easily welched on. Portrayal and betrayal are cousins.”

T. J. Clark (Ibid)

The very act of gratuitously masking a majority of the populace (of many if not most countries, certainly in the West) is part of this stripping away of the human, for the mask hides expression. I think it is interesting, in the same way one can tell models in photo shoots who don’t really wear glasses, that Islamic women achieve such deep expression even veiled, while westerns have no such ability, no such training. I think of south Indian dance, or even Kathakali, or Noh drama, where painted masks, as it were, exaggerate a catalogue of classical ‘expressions’ that carry ritual (and narrative) meaning. The contemporary westerner, far earlier than the pandemic, had already become facially devitalized. Already, even over fifty years, one can see this in cinema. Modern actors, when asked to duplicate silent film acting, usually fail badly. Already the humanness of society was in retreat.

Diego Velasquez (Mars Resting, 1640)

In the Mars painting, Clark sees emasculation. I don’t see that, though I do see a certain unmanning (Venus has left the building). It is the body of Mars that is so remarkable (Clark calls it Velasquez’ most remarkable nude). It is a body on the edge of losing youth. It is not a youthful body at all, but it is one that has claimed its power. The body of a God, after all. But it is dissipated and tired. Sexual fatigue is the first layer, but Mars’ expression goes deeper. The fatigue is spiritual and moral. I can think of no other painting from the 17th century that seems so contemporary. This is the body of an ageing man who works out, watches what he eats, and goes to nightclubs. It is tempting to see a homo-erotic aspect to this, but I think its not the primary reading.

“There is something vertiginous to the figure’s singularity. His expression and his singularity go together. He looks bewildered – a good 17th-century word, meaning ‘adrift in pathless places’. A bewildered male is a bewildering sight. He looks at a loss, and here what the loss is of is sufficiently comically clear. { } It is important that Venus is not in frame, and that what we are left with is a picture of masculinity on its own, mustering itself to confront us – the bare forked animal, not whatever was the force that made it. Masculinity in Mars – this seems to me Velázquez’s thinking – is deeply not a reciprocity, not a form of relationality at all. This is the true uncanniness in the case. Mars is embarrassed, but also deeply at ease in his isolation. “

T.J. Clark (Ibid)

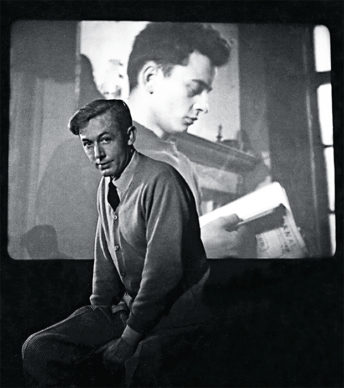

Jaroslav Kocian, photography.

Now, let me move to the new Paul Schrader film (The Card Counter). For William Tillich (Tell) is Mars, in one sense. Not a god, but masculinity bewildered, singular, on its own. Lost, really. It is also a very Dostoyevskian narrative, for it is a film about guilt. William Tell, formally Tillich, is both a cipher and the anti-cipher. A professional card player (and card counter), who drives the casino circuit, playing poker. It is a film of romance, one of the more moving romances in recent memory, and it is a film about regret and lost youth. (Oddly, perhaps, I was also reminded of Faulkner’s Wild Palms) Tell sees in the young companion he picks up, a vehicle for his own redemption. But it is the slow hypnotic quiet of card games, of carpeted hotel hallways and rooms, of the quiet blankness of driving at night. Even the monotony of federal prisons, where Tell was once sentenced. And it is a film about the hideous landscape of kitsch that America has become. The hideous psychological trauma of just leisure in America.

It is linked to Velasquez because it is an allegory of its time. The Card Counter is the survey of Pandemic America, the interior landscape anyway. But exterior, too. It is also Schrader’s most Bressonian film. And it is important to remember Schrader wrote Transcendental Style in Film, some forty years ago, an excellent analysis of Bresson, Ozu and Dryer. In fact it was part of my syllabus for my first year students at film school.

“The enemy of transcendence is immanence, whether it is external (realism, rationalism) or internal (psychologism, expressionism). To the transcendental artist these conventional interpretations of reality are emotional and rational constructs devised by man to dilute or explain away the transcendentaL In motion pictures these constructs take the form of what Robert Bresson has called “screens,” clues or study guides which help the viewer “understand” the event: plot, editing, characterization, camerawork, music, dialogue, editing. In films of transcendental style these elements are, in popular terms, “nonexpressive” (that is they are not expressive of culture or personality); they are reduced to stasis. Transcendental style stylizes reality by eliminating (or nearly eliminating) those elements which are primarily expressive of human experience, thereby robbing the conventional interpretations of reality of their relevance and power. Transcendental style, like the mass, transforms experience into a repeatable ritual which can be repeatedly transcended.”

Paul Schrader (The Transcendental Style in Film)

Oscar Isaac, (The Card Counter, dr. Paul Schrader) 2021.

“A film is not a spectacle, it is in the first place a style.”

Robert Bresson (Rene Briot, Interview with Robert Bresson. Paris: Les Editions du Cerf, I957·)

There is something in The Card Counter that reminds one of the late films of Mike Hodges. Especially perhaps Croupier (1998). But that Hodges is approaching the existential from the other direction. His is a cynical realism that by virtue of having been stared at for so long becomes metaphysical. The Schrader is existential because of letting go of the cynical. Hodges dismisses guilt as sissy stuff, I think. Schrader is, again, more Dostoyevskian. The Schrader film is a sort of book end to his Light Sleeper (Wilhem Dafoe appearing here again, this time as the devil). It is much better and more deeply considered film than Light Sleeper.

It would make sense for Schrader to return so directly to Bresson. He has always seen Bresson as his lodestar, and his admiration for Pasolini, and Antonioni, for Budd Boetticher especially, is apparent in most of his work, it was when Schrader meditated on the middle Bressons, the ones he calls his ‘man in prison’ cycle (Pickpocket, A Man Escapes, Diary of a Country Priest) that he seems to actually find his own most voice. While some of his later stuff was interesting, it felt closer to genre appreciation, genre commentary (and there is nothing at all wrong with that) than it was to something personally transformative – And it is paradoxical, of course, but then Bresson is a paradox. The most radically pure and formal of filmmakers, probably in film history, is also deeply Catholic (Jansenist) and rarely concerned overtly with contemporary issues (his last two colour films are the exception), and yet looms as the most indelibly radical of voices. Schrader has also made a number of just bad films. He destroyed Eddie Bunker’s novel Dog Eat Dog (as if it were beneath him) and while I admired aspects of The Canyons, it was really pretty dreadful. His genre work, Blue Collar and Hardcore, in particular, are excellent and more profound than one might at first think. Schrader is best when he stops having any commercial considerations. Films like Blue Collar and Hardcore were always going to be rejected by Hollywood. Let alone something like Mishima (which I consider a remarkable film, even if a failure).

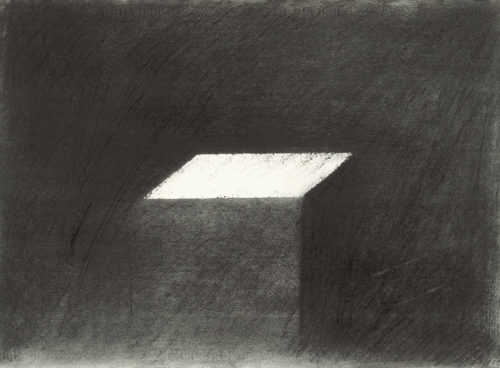

Toba Khedoori

Sometimes the right actor makes an enormous difference. Ethan Hawke was not the right actor (First Reformed) but Oscar Isaac is. And I think it is his voice. Velvety, is how Manohla Dargis described it in the NYTimes. Issac is also oddly a bit like the young Pacino. Those big beautiful, but feminine eyes, and the short guy too tightly wound energy. Only in Isaac, it never surfaces, not really. Almost, but never really, not fully. And in the tormented ‘William Tillich’ Isaac becomes the perfect reader of this new existential catechism. Schrader’s odd Calvinist unconscious, is questioning and answering in the form of Tillich and his young companion, ‘Cirk’ — and Isaac is then, in his 21st century way, a version of Mars Resting. The god of war now reduced to televised poker tournaments in Delaware. At the dog track. The *Racino*.

Robert Bresson, at screening of Diary of a Country Priest.

“Expressive face of the actor on which the slightest crease, controlled by him and magnified by the lens, suggests the exaggerations of the kabuki. “

Robert Bresson (Notes of a Cinematographer)

The problem for Tillich is that his war was Abu Ghraib. He knows there were no Gods there. He knows when Dafoe’s Col. Gordo says to him, ‘I think you’ve got the right stuff’ he means something other than courage and sacrifice. Tillich says to his young acolyte, ‘there is NO justification for what we did’. In Bresson, and in Velasquez the refined and precise class tensions are microscopically inspected.They are less refined in Schrader, but that might not be a detraction. Blue Collar was meant as polemic, and its beautifully executed.

“Could we even say – this would be another solution to the question of Mars being so imperturbable – that Mars seems to know that his humiliation is only a role, a move in an unserious game? His look invites our complicity. This is courtly art. It expects us – Mars expects us – to be properly sophisticated, and share in the cool desengaño.”

T. J. Clark (Ibid)

An unserious game, and an unscrupulous game. Artists like the easy metaphors of gambling. There are countless great gambling films, a number of great novels. Schrader even mentions The Hustler in this film (and Jewison’s early The Cincinnati Kid) This is a sophisticated morality play. Schrader can’t help himself, finally. He has never made an Everyman story.

Workshop of Hieronymus Bosch (Removing the Stone of Stupidity, 1501)

But I would guess that the audience for a portrait such as Mars Resting, or Aesop, has almost disappeared. Reading expressions has eroded, and largely because the face of humans is ever less expressive. Besides painters and philosophers, a number of writers can also be listed as anticipators of the train wreck. Thomas Bernhard, Peter Handke, Kafka of course, Denis Johnson, and Heiner Muller and Juan Rulfo, and Jean Genet.

“But the machines have been built upon a technical way of thinking that Ellul describes as ‘the totality of methods rationally arrived at and having absolute efficiency in every field of human activity.” This way of thinking is the opposite of the organic, the human. It is all about means without ends, self-generating means whose sole goal is efficiency. Everything is now subordinated to technique, especially people.”

Ed Curtin (The Banners of the King of Hell Advance, Sept 2021 Behind the Curtain)

Ed Curtin’s latest piece touches on something of this loss of the human. And he is not wrong to see Reagan’s presidency as a fulcrum of sorts for the intensification of class war. Former CIA director Bush followed, and then Clinton and Bush Junior. And finally the ultimate CIA president in Barak Obama. (see https://covertactionmagazine.com/2021/10/01/a-company-family-the-untold-history-of-obama-and-the-cia/)

Interestingly Ed quotes this piece as well. The train wreck, globally, has CIA fingerprints all over it. But I digress, a bit anyway. Efficiency became a byword for corporate retooling in the 70s. It began before that with Frederick Winslow Taylor (Taylorism again) all the way back to the 1890s. In fact the history of Taylor’s influence is often neglected in looking at the war on the working class.

Fernando Calhau

“In 1911, Taylor explained his methods—Schmidt and the pig iron, Gilbreth and the bricks—in “The Principles of Scientific Management,” whose argument the business über-guru Peter Drucker once called “the most powerful as well as the most lasting contribution America has made to Western thought since the Federalist Papers.” That’s either very silly or chillingly cynical, but “The Principles of Scientific Management” was the best-selling business book in the first half of the twentieth century. Taylor always said that scientific management would usher in a “mental revolution,” and it has. Modern life is Taylorized life, the Taylor biographer Robert Kanigel observed, a dozen years back. Above your desk, the clock is ticking; on the shop floor, the camera is rolling. Manage your time, waste no motion, multitask: your iPhone comes with a calendar, your car with a memo pad.”

Jill Lepore (New Yorker, 2009)

What filmmakers like Bresson represent is interior space unpolluted by Taylorism, unpolluted by Madison Ave. And this has a certain forced aspect, by which I mean artists with any vested interest in the status quo, in bourgeois stability, cannot find this space. Their mental elevator doesn’t go down to sub- basement garage level 3.

John Berger, in one of his last books, or maybe it was the very last book, Portraits, devoted a long chapter to Velasquez. It was a remarkable period of history, Velasquez was 17 when Shakespeare died. His career overlapped with a large number of other great painters, and many in his native Spain. Berger notes that painting deserts is hard because often what you end up with are paintings of sand. The desert is elsewhere (in the sand paintings of Aboriginals for example), just as value is elsewhere than the coin you hold in your hand, or the bank card. Velasquez was something of an anomaly in Spanish art (Goya is another). He was not fanatical, but also not simply a realist in any real sense.

Luca Fontana

“Another way of defining the Spanish landscape of the interior would be to say that it is unpaintable. And there are virtually no paintings of it. There are of course many more unpaintable landscapes in the world than paintable ones. If we tend to forget this (with our portable easels and colour slides!) it is the result of a kind of Eurocentrism.”

John Berger (Portraits)

One aspect of creating art, whether painting or playwriting or poetry, is that the earth is not interchangeable. Berger notes that the natural landscapes of Spain are difficult to paint. Their meaning is obscured, and in the south the desert of north Africa is implied. The landscapes of Renaissance Italy (per Berger) — those one sees in the backgrounds of most Renaissance paintings, the hills beyond the city walls as it were, are far more psychologically nourishing. Spain is difficult, prone to fanaticism. The famous final shot of Antonioni’s The Passenger shot in the province of Almeria, at a hotel (built by Antonioni) perfectly captures the sense of interiority, and the spectre of death.

The key quality of the landscapes of the contemporary West, especially perhaps North America, is how fungible they feel — an intentional by-product of mass advertising, but also of life lived on screens. It is the Spectacle (per Debord) where image and reality are increasingly interchangeable.

Francisco de Zurbarán (drawing, head of monk, 1640 apprx.)

“What happens is that at that moment, when people experience mental intoxication, it doesn’t matter anymore whether the narrative is correct or wrong, even blatantly wrong. What matters is that it leads up to this mental intoxication. And that’s why they continue to go along with the narrative, even if they could know by thinking for one second, that it is wrong. That is the central mechanism of mass formation. And that makes it so difficult to destroy it. Because for people, it doesn’t matter when the narrative is wrong. And what we try to do is we all try to show constantly that the narrative is wrong. But for people that’s not what it is all about. It’s all about the fact that they don’t want to go back to this painful state of free-floating anxiety.”

Mattias Desmet (Interview with The Corona Committee, 2021)

“The scale of the Spanish interior is of a kind which offers no possibility of any focal centre. This means that it does not lend itself to being looked at. Or, to put it differently, there is no place to look at it from. It surrounds you but it never faces you. A focal point is like a remark being made to you. A landscape that has no focal point is like a silence. It constitutes simply a solitude that has turned its back on you. Not even God is a visual witness there – for God does not bother to look there, the visible is nothing there. { } Yet here we need to understand by geography something larger than what is usually thought. We have to return to an earlier geographical experience, before geography was defined purely as a natural science. The geographical experience of peasants, nomads, hunters – but perhaps also of cosmonauts.”

John Berger (Ibid)

I often wonder at this global project that coincides and is a part with the Pandemic. What sort of world do people like Klaus Schwab or David Attenborough want? What does the ideal world of Bill Gates look like? I ask because as far as I can make out, their world is an ugly bloodless anodyne faux pastoral. It is clearly a world without the poor, with primarily white people (a few dark servants is, you know, ok but carefully monitored). Perhaps they don’t themselves know what they desire. Perhaps they have lost the capacity to desire.

Jasper Johns

For example, the pathologizing of desire is now an emerging market for Health Technologies

https://www.bbc.com/reel/video/p09x7xs4/the-little-known-disorder-affecting-5-of-the-us-?utm_source=taboola&utm_medium=exchange&tblci=GiC565_YbM6Om8y64i1v4Y10yQanxygiKK1GyA0yu8o0wCCMjFQo9Ln8kfrwj79N#tblciGiC565_YbM6Om8y64i1v4Y10yQanxygiKK1GyA0yu8o0wCCMjFQo9Ln8kfrwj79N

This incapacity to imagine an ideal strikes me as very likely. Men like Bezos or Musk, or Jack Ma or the Euro aristos who frequent Bilderberg or Davos are not men of imagination (or women). They are adult children. (See Richard Beard’s Sad Little Men, Alex Renton’s Stiff Upper Lip: Secrets, crimes and the schooling of a ruling class (2017), and Joy Shaverien’s Boarding School Syndrome: The psychological trauma of the ‘privileged’ child (2015)) All these books chronicle the elitism and cruelty of class, and in particular the British educational system and its grotesque inequality.

Beard’s book, roundly criticized in mainstream press for being ‘nasty’, though Nicholas Lezard, at the Spectator actually found value in it.

“It is a passionate, well-argued case against a system by which a pool of less than 5 per cent of the population have a disproportionate influence over every significant aspect of our lives. It is also a system which instils in these people dissembling, hypocrisy, snobbery, moral blindness and indifference to anyone else’s suffering. Think of the Prime Minister’s and Foreign Secretary’s decisions to go on holiday just as Afghanistan was about to be catapulted back to the Middle Ages. This book clarifies much: the smirking of Boris Johnson, Dominic Raab and Matt Hancock — they simply don’t care. The reason Johnson is the suboptimal person he is — the kind who refuses to tell us even how many children he has — is because he’s still at school. Even his hair is still at school.”

In the US, class has different characteristics, but the result is largely the same. The destruction of culture is felt across all of this.

Carvaggio (Self portrait as Sick Bacchus, detail.) 1593.

Berger, again discussing Spanish landscapes, writes…“The essence lies elsewhere. The visible is a form of desolation, appearances are a form of debris. What is essential is the invisible self, and what may lie behind appearances. The self and the essential come together in darkness or blinding light.”

One of the themes of 20th century art is that of the exile. Adorno wrote of it often, and others have addressed it because it is ‘felt’ by everyone. The contemporary societies of the West have exiled everyone. Perhaps even the ruling class, though who would know, finally.

Berger has an extraordinary chapter on Rothko. And it worth juxtaposing to his writing on Velasquez. Berger was in his late 80s when he wrote Portraits.

“He is interested in philosophy and, more than anything else, in the theatre and music. He does not become seriously interested in painting until his early twenties. He anglicises his name to Mark Rothko in 1940, when he is thirty-seven. There were how many Jewish emigrant artists of his generation? The number helped to define the twentieth century, which has just ended. Yet Rothko’s art is unique in the way it treats emigration – and not only Jewish emigration. { } Rothko turned painting inside out because the colours he so laboriously created are waiting to depict things which do not yet exist. And his art is an emigrant art, seeking, as only emigrants do, the unfindable place of origin, the moment before everything began. In one of his lectures, George Steiner mentions certain rare languages, used I think by nomads, in which the future is thought of as being something behind the speaker because it is unknowable and the past is thought of as being in front, because it is traceable and evident. It is in this sense that Rothko looks ahead at the one-time beginning. No one can consider seeing without also thinking about blindness. Rothko’s work is very close to blindness. A tragic coloured blindness. The greatest of his canvases are not about going blind, but about trying to take off the blindfolds of colour from which the visible world was (or is again) about to be made!”

John Berger (Ibid)

Kati Horna, photography.

Velasquez, Bresson, Rothko. This is the triumvirate of interiority.

“…it was only from the 1920s, in the shadow of cinema and with the growing dominance of print journalism, that photography became the modulator of the concept of the event. Good photo-reporters followed the action, aiming to be in the right place at the right time.This lasted until the late 1960s, with the standardized introduction of portable video cameras for news coverage. Over the last few decades the representation of events has fallen increasingly to video and was then dispersed across a variety of platforms. As television overshadowed print media, photography lost its position as a medium of primary information. It even lost its monopoly over stillness to video and then digital video, which provides frame grabs for newspapers as easily as it provides moving footage for TV and the Internet. Today, photographers often prefer to wait until an event is over. They are as likely to attend to the aftermath because photography is, in relative terms, at the aftermath of culture. What we see first ‘live’ or at least in real time on television might be revisited by photographers depicting the stillness of traces.”

David Campany (Photography and Cinema)

The aftermath of culture is an apt phrase, even if Campany didn’t quite mean it the way I do — and Campany is always a valuable read and the best critic of photography alive. He makes some useful notes, too, on Bresson and what acting means in cinema. (and noting the circus backgrounds of both Buster Keaton and Cary Grant, both tumblers among other things, not to mention Burt Lancaster, who did run away and join a circus. The grace of all these actors is very pronounced when one looks at their work today.) Campany makes an astute observation about Grant’s performance in ‘North by Northwest’…“Cary Grant’s entire performance is a series of balletic swoops and pirouettes strung between archly frozen poses.”)

This is all relevant to the exteriorizing (sic) of emotion and the attendant immobilization of faces. The physical grace of a Lancaster is replaced with the android action figure stiffness of a Stallone or Schwarzenegger.

Mark Rothko

It is not exactly immobilization, though. For it feels as if expressions have been codified, that facial expressions occur in short-hand, as it were. Incomplete and partial. Taking the place, standing in (perhaps if only for the sake of duration) is an exaggerated advert for humanness. I once called it the ‘shrieking ego’, and its often a wide open mouth, stretched wider than normal, with lots of teeth, and eyes open wide. This is a popular pose for magazine advertisements. Entertainment has bled into everything. And now, the normalizing of class hierarchies is the most repeated trope in Hollywood. Class is as eternal and natural as capitalism itself. They do go together, after all.

Facial expressions and their retreat, their increasing shallowness, corresponds, naturally, with the erosion of language. The loss of verbal skills. And then with listening. One of the amusing parlour games is to look at various movie stars in roles that demand intelligence (say a psychiatrist, or scientist). I remember Richard Gere as a shrink, and I can remember Bruce Willis, too. The idea was simply beyond them. Intelligence, erudition, learning — they had no idea how to do that. Make ‘smart faces’ for the camera. That was Willis’ solution, while Gere furrowed his brow, almost for the entire movie as I recall. Furrow = thinking. Or director Ron Howard when he created a montage to represent the interior of John Nash’s mind, the kind of thing a six or seven year old might create to represent thinking.

Lourdes Grobet, photography.

“Positivist scientific reason protracts existing socio-economic relations, becoming an instrument of capitalist power. As long as scientific and technological developments benefit capitalist relations of production, reason is perverted to an atavistic ideological force, authenticating administered societies and rationalization.”

Antonios Vadalos (Perversions of Fascism)

The science of the Covid narrative is patently absurd. As is the bizarre insistence on 100% vaccination. Supply chain disruptions are now the fault of the unvaccinated. (how far off are the first pogroms?). It is interesting that Vadalos writes…“…science becomes the aftermath of a hegemonic type of rationality, contagious to all aspects of human civilization and nature.” The alchemy of word choice. Which brings me to a final thought; it is clear that society as a whole is less literate than fifty years ago, certainly less than a hundred years ago. And there are obvious losses in vocabulary and losses in grammar. But there is also a loss of the mysteries of text and speech — the mythic and sacred structural truths.

“Elizabeth Archibald, quoting from Chiarini’s study on Appolonius of Tyre, adds that “incest is not only the first sin, but also the first riddle”. While the substance in the queen’s riddle is clear on this point, it is important to note that all riddles have the quality of merging what is in a certain sense meant to remain separate or forbidden to conjoin.”

Michael Elias (Neck Riddles in Mimetic Theory)

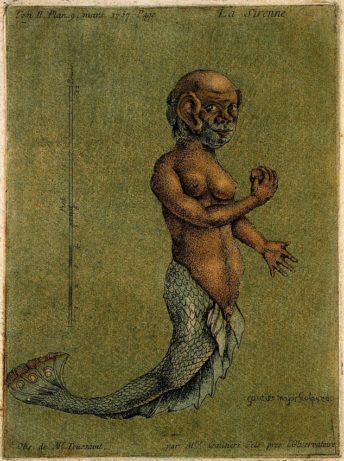

J.F. Gautier, aquatint illustration of mermaid. 1758.

Huizinga noted that riddles were “a sacred thing full of secret power, hence a dangerous thing”. (Johan Huizinga, Homo-Ludens, 1950)

Neck riddles were riddles that if not solved resulted in beheading. Nearly all ancient folk texts contain riddles and almost all grant them enormous importance. Science, the mechanistic one dimensional form one sees today is that which has drained myth from reason. The idea of progress came very early (if not from its inception) to be about efficiency — foreclosing the idle thoughts, day dreams, even fantasies. The fantasy became sexual, prohibitive, and alienated. Pornography itself is breakage of Taylorism, operatively. It is the acceptable damage on the periphery of advanced capitalism. Porn is control.

Mechanistic morality is expressed in the new caste of unvaccinated. This (per Demetz) staves off the terror.

“The primitive fear of the state of disintegration underlies the fear of being dependent; that to experience infantile feelings of helplessness brings back echoes of that very early unheld precariousness, and this in turn motivates the patient to hold himself together … at first a desperate survival measure _. gradually. __ built into the character … the basis on which other omnipotent defense mechanisms arc superimposed.”

Joan Symington (The survival function of primitive omnipotence. lnternational Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 1985)

That free floating anxiety is the fear of disintegration, at bottom. Screen habituation, the ubiquity of social media, all the various electronic/digital platforms — in the West anyway — have disrupted the developmental sense of contact, of space. As Joyce McDougall noted, closeness must be concrete rather than felt. Because its not ‘felt’. The delusions of the ruling class, which I have come to believe are more advanced and also less treated despite access to health care, are imposed on society, top to bottom. Their own psychological poverty must be compensated for, or duplicated, in the lower classes. They are tearing away the humanness from culture, but only up to a point because they don’t really know the ingredients for human. Just as they don’t experience desire, only an obsessive impulse for power and hoarding. If Bezos or Musk didn’t have wealth to hoard, they would be like those old men in pension hotels, their rooms stacked to the ceiling with fading and deteriorating magazines, and old milk cartons.

Diana Thater

“Both Rosenfeld and Meltzer conceptualized this character structure as a delinquent gang or criminal Mafia within the mind, a covert and collusive network of renegade malignant objects in hierarchical organization that provide (for the infantile self) a reliable source of protection from madness, psychic pain, and anxiety in return for absolute obedience, loyalty, and constant acts of tribute. In short, the normally dependent baby-self is rigidly controlled within a sociopathic internal family of objects.”

Joyce McDougall (Framework for the Imaginary)

Western rationality has paved the way for fascist mythological irrationality. ‘Trust the science’ is a malignant fascist slogan beneath its homey common sense surface.

To donate to this blog, and to the Aesthetic Resistance podcasts ..use the paypal button at the top of the page.

I Know the blind or near-blind know the

true uncanny light hides in the darkest

alleys of the fire and includes tabood

taylorist-suppressed desire. Remember

Ulysees’ and Prometheus’ fates, or stare

at your naked, often wild, nature. The obedient

are relieved of this jeweled burden. It

remains a task for the courageous or crazy.

Thank you, John, for illuminating the strange

geometry or musics of these paths.

As I prepare to re-read Dostoyevsky’s “Diary

of a Writer”, I think about Belazquez or Goya

would express if they had staggered from their

spectular Fords onto the neon carnival of a

“South of the Border” recreation stop, by I-95 in

Carolina, I forget if it be North or South, the

memories of those trips now as in a semidream fog..

And the concretely grotesque hot dogs oozing with

giant secretions of red and yellow. Disintegration

of a riddle imperial self, perhaps.

This part of the essay strikes me as remarkable:

…….. I often wonder at this global project that coincides and is a part with the Pandemic. What sort of world do people like Klaus Schwab or David Attenborough want? What does the ideal world of Bill Gates look like? I ask because as far as I can make out, their world is an ugly bloodless anodyne faux pastoral. It is clearly a world without the poor, with primarily white people (a few dark servants is, you know, ok but carefully monitored). Perhaps they don’t themselves know what they desire. Perhaps they have lost the capacity to desire.This incapacity to imagine an ideal strikes me as very likely ……….

Those same elites are also accused of end-of-history utopianism, with an underlying assumption that utopianism is a perilous thing. (1)

Their supposed incapacity to desire, or imagine an ideal would just make them typical in the present-day world. Very few express such capacity, in public at least, and when someone ventures in that direction, like Srnicek and Williams in “Inventing the Future,” the vision they bring is not all that much warmer or more fleshed out than that of, say, K. Schwab (if he actually wrote that book). (2)

“[A]s far as I can make out, their world is an ugly bloodless anodyne faux pastoral.” – alright.

But, it is also a world that tried to base itself on science & technology, while building a strong hierarchical order, as if trying to wed the most attractive parts of the ancient and the modern, a world that promises an elimination of war, chaos, suffering … and one can reasonably fear that most people could subscribe to such a thing.

There is much more that can be said on this matter, from a variety of angles, but so much for here and now.

Hi John – totally off topic but I see you were rightly disgusted at that Darren Allen Marx-trashing essay which Off Guardian unaccountably posted. I wrote a rebuttal of it in the comment section only to realise whilst writing it that I didn’t even need to mention Marx at all. The essay refutes itself by going into that pseudo-profound Kantian mode that negates the very possibility of critique. It’s the usual ethereal anarchist bullshit.

The exchatological, as well as local or imminent, locus of

theatre, i.e, of religion should be the polis or

the streets(the ordinary trajectories of common

cultural praxis and practice). Somwhat paradoxically,

the Frankfurt School-such as Adorno & Marcusee- was almost

coincident with the reactionary Austrian school in Political

Economy.

But, I suspect that the following article re. the looming

economic disintegration of our beloved empire of horrible

spectacles may yield valuable survival tips for followers

of the great stages: The exchatological, as well as local or imminent, locus of

theatre, i.e, of religion should be the polis or

the streets(the ordinary trajectories of common

cultural praxis and practice). Somwhat paradoxically,

the Frankfurt School-such as Adorno & Marcusee- was almost

coincident with the reactionary Austrian school in Political

Economy.

But, I suspect that the following article re. the looming

economic disintegration of our beloved empire of horrible

spectacles may yield valuable survival tips for followers

of the great stages: https://www.goldmoney.com/research/goldmoney-insights/a-tale-of-two-civilisations

agreed. (Dorian)

from Guy Zimmerman

Beautiful post, John. We’ve discussed the Carson book before and your comments here seem spot on to me. What’s so remarkable is how swiftly coinage transformed every last aspect of culture across the Greek world, a speed we can appreciate due to the equally swift transformation that has happened with social media. I also think your take on Disney is very apt. I have some vague memory of John Berger writing on Disney’s brand of anthropomorphism in a very astute way. I recall reading a book on design by one of Disney’s main artists, and being struck by how visually sophisticated Disney was. I view the emblematic Mickey Mouse face, for example, as a kind of visual spell that hooks us by producing a little life–all those upward leading curves and round forms just have that affective impact. Recognizing the market value of that little addictive lift–the love American’s have for uncomplicated sentiment, etc–and you become a titan of industry. Depressing but in a world in which the self is first property everyone is miserable so it’s a seller’s market.

Hope all’s well over there…

Onward,

G

SHINING Like a Red Rubber Ball

Hallow End Wees … https://www.counterpunch.org/2021/10/29/wolfs-glen-for-halloween/