Vittore Carpaccio, 1490s (Venice).

“Go to the ant, thou sluggard; consider her ways, and be wise:

Which having no guide, overseer, or ruler,

Provideth her meat in the summer, and gathereth her food in the harvest.”

Proverbs 6:6-8

“…it is more probable that worms and flies and caterpillars move mechanically than that they all have immortal souls.”

Rene Descartes (Discourse on Method)

“Generally speaking, when the cognitive revolution pushed the study of learning into the background, with it went much of the interest in the classic epistemic problems of knowledge acquisition with which philosophers and psychologists had struggled for decades. For the most part, contemporary cognitivists have been captured by the

problems of knowledge representation and use rather than with an examination of its nature and acquisition. Similar sentiments have been recently expressed by Glaser (1990) in his overview of the relationship between learning and instruction. Interestingly, he identifies the influence of the information-processing models as one of the primary

reasons why learning has been neglected in recent decades. He specifically cites Newell and Simon’s (1972) arguments that the study of performance, in an information-processing format, should take precedence over examinations of learning and development as a critical element in the drift away from learning.”

Arthur S. Reber (Implicit Learning and Tacit Knowledge)

“If a lion could speak, we could not understand him.”

Ludwig Wittgenstein (Philosophical Investigations)

Information processing, rather than learning. One sees the stepchildren of this trend in how computer modeling is used. The Corona models (like most climate models) have been stunningly wrong. But then this is also how institutional “studies” are initiated and what motivates those conducting the studies. The EU provided a lot of money for “Corona studies” and so there was a economic motivation to find sensational predictions. Now I want to talk later a bit about predictions, because this is something tied into AI and game theory and all manner of other very trendy and popular areas of research.

Henri Rousseau

One of the reasons I keep writing about AI is that the entire construct of an artificial intelligence has become both a symbol and metaphor for contemporary thought, and, is part of this ongoing reshaping of human consciousness.

I admit I am surprised how many people believe in the entire project of AI. Clearly it holds something very appealing that people WANT to believe in. And a key element in this is the idea of predictability. And predicting means controlling. So, in one sense, there is nothing new in this desire to foretell the future.

Now the first problem when discussing “consciousness” is that finding a definition for that word is nearly impossible.

“Moreover, the explicit dualistic beliefs of children in Western cultures get less strong with age (Bering 2006). This suggests that dualism is the default setting of the folk-psychological system, which gets weakened by cultural input in scientific cultures—at least at the level of explicit verbal expression—rather than depending on such input (Riekki et al.2013;Willard & Norenzayan 2013; Forstmann & Burgmer 2015). Indeed, dualist intuitions are prevalent in both children and adults, even in cultures whose norms discourage overt attention to mental states, albeit becoming weaker as a function of exposure to Western education (Chudek et al.2018).”

Peter Carruthers (Human and Animal Minds)

Siron Franco

There is an enormous amount written on the subject of “qualia” , and I’m not going to go over it all here. But one point is worth noting, and Carruthers touches on this, too; the belief in qualia, that is a belief in non-physical properties that are attached or linked causally to physical properties. That is, the belief in qualia is based on a sort of psychological need to believe in them. That the world (or rather “I”) makes more sense if qualia exist in it.

Now as a sort of side bar, its interesting that in so much of the literature (philosophical) on the ‘other minds’ problem (and mind/body problem) that zombies are used as thought experiments. I’m not sure what this suggests, but its interesting. Its like we need zombies as a construct to make sense of ourselves.

Anyway, the question of animal consciousness has become a big topic over the last twenty years. Why it should do so now is an intriguing question, but my guess is that the rise of AI has something to do with it.

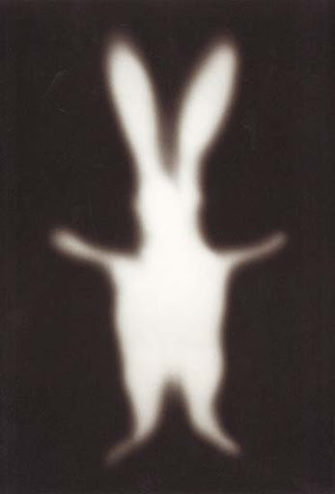

Adam Fuss, photography.

Now, as I tend to do, I’m going to digress briefly here. One of the aspects of thinking about consciousness, and more, about the consciousness of others, is the visual impression people make. Aristotle was big on the study of physiognomy — and he at one point suggested men with hooked noses were vicious, like the hawk. So the masks of greek tragedy followed this advice. Leslie Zebrowitz, a social psychologist, wrote a really fascinating book titled Reading Faces…

“Darwin almost lost his passage on the Beagle because the captain, was highly influenced by the Swiss physiognomist Johann Caspar Lavater, whose writings were widely read from the time his book ‘Essays on Physiognomy’ was first published in 1772, This book was regularly reprinted for a hundred years in German, French, English, and Dutch, and two modern versions were published in Lavater’s home country of Switzerland as late as 1940, bringing the grand total to 151 editions in. various languages. The eighth edition of the Encyclopedia Britannia documented the enormous impact of this book on social interactions: “In many places, where the study of human character from the face was an epidemic, the people went masked through the streets.”

This was accepted science for a hundred years. But it is also suggestive of how important the face actually is, or rather, the importance of what a society deems the human. The loss of humanness is what one is seeing today both in screen habituation and in the Covid hysteria.

Dominique Stroobant

There is an entire discussion to be had about evolutionary psychology. David Buss was the front edge of this movement that began, for the most part, with his book Evolutionary Psychology, published in 1998. Buss is very big on the TED talk circuit and he’s amusing and pretty entertaining. But like Stephen Pinker and Jared Diamond, this stuff is in the end deeply reactionary. And that, actually, should be fairly obvious. And of course Richard Dawkins who I wrote about last post. The reason I bring this stuff up again is that it exhibits the same extreme conservatism that, in the end, game theory exhibits and AI exhibits. They are all of a piece, in fact.

Louis Menand had an amusing summation of Pinker…(in The New Yorker a decade back):

“In general, the views that Pinker derives from ‘the new sciences of human nature’ are mainstream Clinton-era views: incarceration is regrettable but necessary; sexism is unacceptable, but men and women will always have different attitudes toward sex; dialogue is preferable to threats of force in defusing ethnic and nationalist conflicts; most group stereotypes are roughly correct, but we should never judge an individual by group stereotypes; rectitude is all very well, but ‘noble guys tend to finish last’; and so on.”

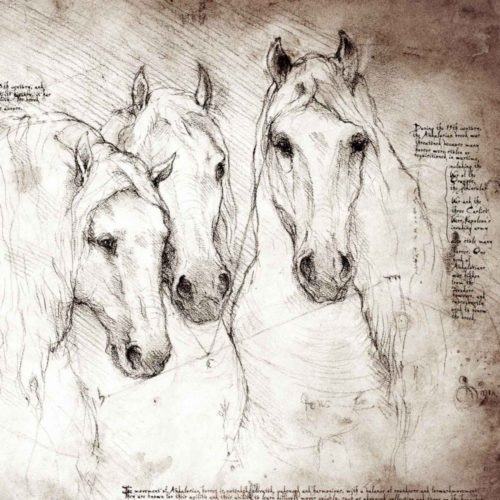

Da Vinci

But the point is that I am finding several threads in all this, the AI groupies, the game theory writers, and evolutionary psychologists – and those threads start with their reductiveness. The vast unknown centuries, ten thousand centuries, in which man roamed the planet, are treated as if a couple weeks had elapsed. The pinched vision, historically, is most obvious in (of course) the evolutionary psychologists. But like zombies, there is something deeply attractive in this stuff. And I suspect these branches of study all influence each other. And all of them, but especially AI and evolutionary psychology, premise their logic on a sort of folk history, an almost kitsch mythos of rugged individualism, and frontier fortitude. That is clear with the psychologists here, but even with AI the presentation of the metanarrative, if you will, is one with a Davey Crockett adventurism. This may seem opaque to some degree, but I will attempt to clarify a bit below.

Now let suggest a book that is a wonderful corrective to the Dawkins and Diamonds and Pinkers of the world…Other Minds; the Octopus, the Sea, and the Deep Origins of Consciousness, by Peter Godfrey Smith. Perhaps it helps that Godfrey-Smith is a philosopher.

Recently someone said to me, in a conversation about overrated artists, in particular musicians and composers, that he hated Coltrane. I said, well, I can’t say I “like” Coltrane because I think he is more philosophy than music. I think that way about Bartok, too, and Berg. But I can say I enjoy (!) Bartok and Berg. And then I wondered what I actually meant. Maybe I didn’t really mean anything. I was just talking. This happens, and the older you get the more often you recognize this phenomenon. Still, I thought later that I had perhaps touched on something important but hadn’t yet figured out how to articulate it. Now, in a very roundabout and obtuse way this brings me back to Godfrey-Smith and the sea. And that in turn takes me to Melville and Shakespeare and even Robert Stone, or Conrad, or any number of other writers. If the earth if a few billion years old, animals didn’t appear, we are told, until about a billion years ago. Before that was just water, really, endlessly moving, sloshing in this direction and then that, and there were a lot of storms and changing severe weather. And there were single cell entities. And the awe one feels when contemplating “this” version of Earth is that of trying to imagine an earth without anything or anyone to observe it. The vastness of time corresponding to the vastness of space.

Modest Cuixart

“I to the world am like a drop of water

That in the ocean seeks another drop,

Who, falling there to find his fellow forth,

Unseen, inquisitive, confounds himself.”

William Shakespeare (Comedy of Errors)

An earth that for hundreds of thousands of years went unobserved. Or so we assume. For that is the thing, one of the last places that can be contemplated as an area of the unknown is the past. The deep past. And then evolution. And whatever objections one might have to this theory, I think it is hard to argue that some form or other of evolutionary process took place. And if one traces common ancestors back, you eventually get the sponge or ctenophore (comb jellies). But this is 700 million years ago. And then early nervous systems (jellyfish, anemones, etc), and so it went, with the always nagging question of what made reaction become action, when did life stop responding to stimuli and simply creatively act?

The answer lies somewhere in that “Cambrian explosion” (as geologists like to call it) of about 500 million years ago..give or take a few centuries. There was a precursor period now called Ediacarian, and it is here that it seems there are fossils of sorts (imprints on rock) of countless evolutionary dead ends. Things that self propelled (like mollusks perhaps) but did little more. All this taking place quietly on the bottom of the ocean, in stews of bacteria and microbes. Now one might ask what this has to do with AI or art and culture for that matter. And I think it has, finally, a lot to do with it.

Teresita Fernandez

“ One theme that has emerged fairly consistently, though, is that the Ediacaran world was a rather peaceful one, a world largely without conflict and predation.The word “peace” might not be apt, as it suggests a kind of considered friendship or truce. Rather, the Ediacarans appear to have had very little to do with each other. They munched on the mat, filtered food from the water, and in some cases roamed around, but if the fossil evidence is any guide, they hardly interacted at all.”

Peter Godfrey-Smith (ibid)

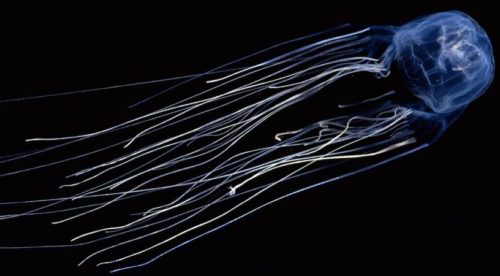

One of the mysteries of the Ediacaran period is found in the jellyfish. For even these early jellyfish had stingers. Why?

The ‘Cambrian Explosion’ is dated at 540 millions years ago. Suddenly vertebrates appeared, fish and a good deal of predation. There is no real explanation for this sudden emergence of new evolutionary forms of life. There is climatic speculation, but nothing that really ‘explains’ this eruption of suddenly far more complex life forms. Sometime during the Cambrian period the first “eyes” appeared — both camera eyes and compound eyes ( spiders etc). And this marked something significant. Was it an awareness, did seeing the world around you change existence? No doubt, but why did eyes appear?

“The bilaterian body plan arose before the Cambrian, in some small and unremarkable form, but it became the bodily scaffold on which a long series of increases in behavioral complexity was laid down. Early bilaterians also have another role in this book. Sometime soon after they appeared, probably still in the Ediacaran, there was a branching, one of the countless evolutionary forks that take place as the millennia pass. A population of these animals split into two. The animals who initially wandered off down the two paths might have looked like small flattened worms. They had neurons, and perhaps very simple eyes, but little of the complexity that was to come. Their scale was measured perhaps in millimeters. After this innocuous split, the animals on each side diverged, and each became ancestor to a huge and persisting branch of the tree of life. One side led to a group that includes vertebrates, along with some surprising companions such as starfish, while the second side led to a huge range of other invertebrate animals. The point just before this split is the last point at which an evolutionary history is shared between ourselves and the big group of invertebrates that includes beetles, lobsters, slugs, ants, and moths.”

Peter Godfrey-Smith (ibid)

Chironex fleckeri (Box Jellyfish)

There are countless theories (the development of two nervous systems in a single body — a light sensing top system and an eating system, and they migrated toward each other until they began to cooperate)…but all these theories are only descriptive, they suggest how it happened, maybe, but not why and nobody has much of a timeline for this stuff. How long did those nervous system migrations take? Ten million years? Twenty? Who knows. Or was it sudden? Did there appear one freak generation of clam?

Godfrey-Smith details the evolution of the octopus brain (and to some degree its near relative the cuttlefish). I would encourage reading the entire book. For it raises interesting questions about intelligence, about the idea of AI specifically, but also about social behaviour and group relations. For somewhere in the distant past the cephalopods branched out, a curious branch to be sure, and evolved their own unique form of smarts.

A footnote to the cephalopod branch is the Nautilus. Perhaps the most unique being on the planet, the Nautilus is, from all anyone can surmise, unchanged for two hundred million years. It was part of that curious branch that is cephalopod but there it stopped. Apparently perfectly happy with being just a Nautilus.

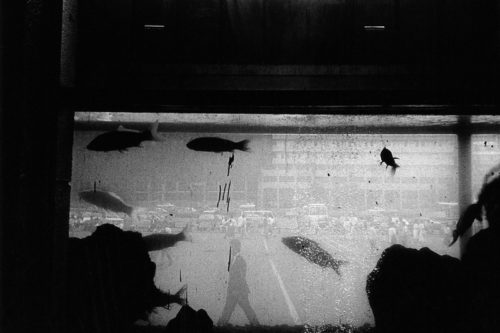

Abul Kalam Azad, photography.

A few final notes on octopi and animal intelligence.

“I described how the early history of animals, insofar as we know it, led to a fork with one path running forward to chordates, like us, and the other leading to cephalopods, including the octopus. Let’s take stock and compare what arose down the two evolutionary lines. The most dramatic similarity is the eyes. Our common ancestor may have had a pair of eyespots, but it did not have eyes anything like ours. Vertebrates and cephalopods separately evolved “camera” eyes, with a lens that focuses an image on a retina. The capacity for learning of several kinds is also seen on both sides. Learning by attending to reward and punishment, by tracking what works and what does not work, seems to have been invented independently several times in evolution. { } Octopuses, like us, seem to have a distinction between short-term and long-term memory. They engage in play with novel objects that aren’t food and have no apparent use. { } We have hearts, and so do octopuses. But an octopus has three hearts, not one. Their hearts pump blood that is blue-green, using copper as the oxygen-carrying molecule instead of the iron which makes our blood red. Then, of course, there is the nervous system—large like ours, but built on a different design, with a different set of relationships between body and brain. { }The octopus is sometimes said to be a good illustration of the importance of a theoretical movement in psychology known as embodied cognition. These ideas were not developed to apply to octopuses, but to animals in general, including ourselves, and this view has also been influenced by robotics. One central idea is that our body itself, rather than our brain, is responsible for some of the “smartness” with which we handle the world. Our body’s own structure encodes some information about the environment and how we must deal with it, so not all this information needs to be stored in the brain.”

Peter Godfrey-Smith (ibid)

Koo Bohnchang, photography.

Godfrey-Smith takes issue with the science of robotics here, because he points out the octopus fits no other paradigm. It is neither brain controlled, nor body controlled. In fact its body is more or less its nervous system. And it is quite possible that octopi arms often wander off by themselves without the central brain being aware of it. Sentience before consciousness. What does it feel like (sic) to be an octopus? One cannot reasonably ask what does it feel like to be a bacteria. But one can ask what does it feel like to be a dog, or a chimp, or an octopus. Why is this? The first answer is because they are somewhat like us — as listed above. Not that much, but there are similarities. My take is that even Godfrey-Smith exaggerates those similarities. But, one example worth mentioning was an experiment done on frogs by David Ingle in the 1960s. He rewired the frog’s brain (which regenerates, interestingly) to “see” backward, as it were. The frog snapped at prey to its right when the prey was actually to its left. Melvin Goodall wrote of this experiment…“So what did these rewired frogs “see”? There is no sensible answer to this. The question only makes sense if you believe that the brain has a single visual representation of the outside world that governs all of an animal’s behaviour. Ingle’s experiments reveal that this cannot possibly be true.”

So, what conclusion does this suggest? Only that sensory operations in animals can and often do take place outside what we call “experience”. And that somewhere along this long evolutionary path sensory input came together to form an interior world, a subjectivity. And that subjective world, the human subjective, seems unique. And this is likely linked to the ability to create a language.

Romulo Maccio

“All forms of perception are “subjective” in the sense that they represent only those aspects and properties of the world that can be detected by an organism’s sensory transducers. Hence all perception is subjective in the sense of being partial. Moreover, once organisms reach a stage of cognitive complexity where they start to encode some sort of model of the surrounding world through their sensory contact with it, then the result is subjective in an even deeper sense. For what is represented will only comprise those aspects of the world that potentially matter to the organism (whether this is explicitly represented in the organism’s values, or implicit in the lifestyle that has been selected for it by evolution).”

Peter Carruthers (ibid)

Carruthers’ book is very good, I think. And he emphasizes that our concept of phenomenal consciousness is always first person. And this seems to me hugely important. Carruthers’ also notes that one important question about consciousness is why it should be so hard to define.

Now I want only briefly mention the global workplace theory of consciousness. I say briefly because its a very complex topic and I am simply not the person to elaborate all the intricacies involved. And Carruthers’ has as good a chapter on this theory as any I’ve found. The problem is, finally, I’m not sure there is a way to even approach a definition of consciousness. Sentience, yes, but not consciousness. And the global workplace theory is useful, but in the end I find it as flawed as the ‘qualia’ theory. Now, the crucial aspect of consciousness, as least as we conventionally understand it, is language. What separates our inner lives from those of baboons or Dolphins or octopi is our language. And while dolphins do have a language of sorts, its nothing remotely as complex as human language.

Dalibor Chatrny

Godfrey-Smith mentions Lev Vygotsky, a Soviet psychologist (one of the few and one who sadly died in his early thirties) whose book Language and Thought remains an important contribution to the studies of childhood development. And Vigotsky had this idea that I think is quite profound: and that is that as children learn and mature their language develops in two branches, one inner and one outer or public. That inner voice is something many people are, today, actively discouraged from hearing.

“For Vygotsky, inner speech has a role in what is now called executive control. Inner speech gives us a way of performing actions in the right order (turn off the power first, then unplug the machine), and exerting top-down control over habits and whims (don’t eat another slice). Inner speech can also be a medium of experiment, for putting ideas together to see what comes of the combination (how would things look if I could travel as fast as light?).”

Peter Godfrey-Smith (ibid)

Lev Vygotsky

Now, I have called this re-narration. And I was speaking in a context of creative writing, or really, for any creative act, or, any engagement with artworks. And inner speech is tied into mimesis as well. So while baboons or octopi exhibit something ‘like’ consciousness, it is a different order from human.

Now Vygotsky was a great admirer of Eisenstein and Russian symbolists, as well as a fan of the theatre. And what is significant in his work is how closely it is tied into the social and in particular the cultural and to art.

“…central to the approach outlined by Vygotsky and his followers is that of development. Vygotsky’s Russian contemporaries-the evolutionist-biologist V. A. Vagner and A. N. Severtsov-were producing remarkable ideas in this area. Vagner insisted that there must be a significantly tighter connection betwee.n psychology and general biology, especially evolutionary theory. He identified the dangers oftoo close a tie between psychology and physiology, a tie that could lead psychology down the wrong path.”

V. P. Zinchenko, in introduction to James V. Wertsch (Vygotsky and the Social Formation of the Mind)

Vygotsky saw the origins of language as the foundations of consciousness. He also saw Marxism as the basis of what science should be and do — and he abhorred the empiricists in psychology popular at the time in Russia.

Aldemir Martins

“Formerly, psychologists tried to derive social behavior from individual behavior. They investigated individual responses observed in the laboratory and then studied them in the collective. They studied how the individual’s responses change in the collective setting. Posing the question in such a way is, of course, quite legitimate; but genetically speaking, it deals with the second level in behavioral development. The first problem is to show how

the individual response emerges from the forms of collective life.”

Lev Vygotsky (Language and Thought)

I hope to write more on Vygotsky in coming posts. For the purposes here…let me add another quote…

“Any function in the child’s cultural development appears twice, or on two planes. First it appears on the social plane, and then on the psychological plane. First it appears between people as an interpsychological category, and then within the child as an in interpsychological category. This is equally true with regard to voluntary attention, logical memory, the formation of concepts, and the development of volition. We may consider this position as a law in the full sense ofthe word, but it goes without saying that internalization transforms the process itself and changes its structure and functions. Social relations or relations among people genetically underlie all higher functions and their relationships.”

Lev Vygotsky (ibid)

In terms of animal intelligence, definitions of consciousness (and even sentience) the social factor looms are hugely significant.

Axel Krause

But it does in humans, too. I have watched my three boys, all under the age of four, and how learning is tied to socialization. They learn from each other, from their brothers, parents, and at kindergarten. They learn by playing and through mimetic fantasy and creativity. Now, Carruthers is not totally wrong by any means when he speaks of phenomenal consciousness as a first person experience. But there is no first person to recognize itself without the social. But this takes us back to Wittgenstein, too, again. The point here is that the entire AI project ignores social learning, and social intelligence, as it were. And the mimetic factor in all subjective experience.

“Mimesis is the affinity of subject and object as it is felt in one’s knees on seeing someone else stumble on theirs.”

Robert Hulot-Kentor (Things Beyond Resemblance)

“In relation to individuality, Adorno follows up with the question of identity which is intrinsically related to fascism, and this emerges as the radical and logical end of the culture industry. The existentialistic view that the problem takes on, discloses the mimetic nature of every activity, which is held in the course of work as an certain immanence that is determined by the totality of various modernistic cultural phenomenons.”

Kristijonas Jakevičius (Concepts of Mimesis in Adorno)

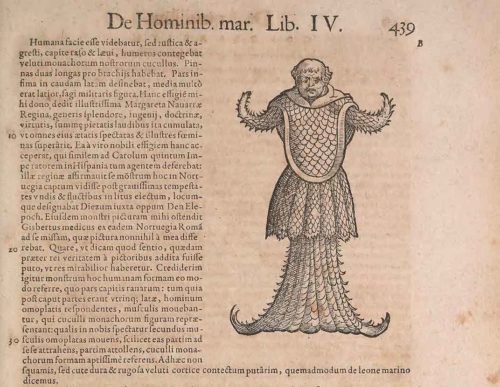

“Sea Monk”, Conrad Gessner, 1664.

Even octopi have a political dimension. The issue here is that AI as its being marketed today is basically fascistic. It eliminates the human as much as possible, and does this by first restricting a consideration of the social. Its a first person experience much as owning a new car is a first person experience. The vast processing ability of super computers has not much to do with consciousness. And all the “mirroring” of brain activity will do nothing to replicate consciousness. So why does such stuff garner such interest, why is it praised by pundits of the West, by the lords of western capital? That is the question, I think. And part of it has to do with this shift toward open schemes for population reduction, limiting of rights and travel, and the insistence on the computer as the model for progress. But the AI program, overall, exhibits a hostility to the human, as well.

There is a quote Jakevičius doctoral thesis that I think is relevant here.

“These are words in which decisive deep-historical (aeschichtlich) shifts show up, where little noticed but colossal alterations in the human world are at work in language. The Greek word techne is a good example: it once named the knowledge implicit in the making of something, both in art and technology. Later these become distinct, even antagonistic.“

Timothy Clark (Heidegger)

Milwaukee Field Museum. Photographer unknown.

This from a book on Heidegger’s aesthetics. I can say, Heidegger was aware of the antagonistic shifts in language, he was the creator of many of them. But this point is germane. The road backward linguistically, regards technology, is long. And it is important to reconcile consciousness with learning rather than information processing. The ‘making’ of something became closer to the owning of something. This already true in Attic Greece.

The de-linking of mimetic feeling from the ‘objective’ world is also a space for the manufacture of ersatz myth. And the politics of Covid and the quarantine carries with it a quality of this fake mythology. And it is a mythology that reflects back something of the Nazi/fascist project. Ansgar Hillach, back in 1979, on Benjamin’s essay on Junger and National Socialism writes…“the technical waging of war which led to an upheaval in the national consciousness.” And that regressive submission to the feudal mythology of the military. The technical aspect had to be injected with kitsch romanticism, not just patriotic fervor and jingoism, but with a metaphysical or quasi religious dimension. Jeffrey Herth notes in another article on Junger and reactionary modernism that National Socialism was utopian anti-modernism. (Jeffrey Herf, Reactionary Modernism) The Nazi paradox revolved around technology. And Herth devotes a chapter to the influence of Heidegger on reconciling volkish mythology with technological progress. Heidegger was, in a sense, among the most profound influences creating the atmosphere for Nazi culture.

“We live in an era of technology. The racing tempo of our century affects all areas of our life. There is scarcely an endeavor that can escape its powerful influence. Therefore, the danger unquestionably arises that modern technology will make men soulless. National Socialism never rejected or struggled against technology. Rather, one of its main tasks was to consciously affirm it, to fill it inwardly with soul, to discipline it and to place it in the service of our people and their cultural level. National Socialist public statements used to refer to the steely romanticism of our century. Today this phrase has attained its full meaning. We live in an age that is both romantic and steellike, that has not lost its depth of feeling. On the contrary, it has discovered a new romanticism in the results of modern inventions and technology. While bourgeois reaction was alien to and filled with incomprehension, if not outright hostility to technology, and while modern skeptics believed the deepest roots of the collapse of European culture lay in it, National Socialism understood how to take the soulless framework of technology and fill it with the rhythm and hot impulses of our time.”

Joseph Goebbels (Deutsche Technik 1939)

Thomas Eakins

Filling ‘techne’ with “soul”. That was the marketing slogan.

“Reactionary modernism was an important part of totalitarian dictatorship in power in several senses: It offered a comprehensive explanation of a supposed nonpolitical phenomenon, thus demonstrating the capacity of nazism to provide answers to all of life’s dilemmas; it gave the Nazis a political language of movement and dynamism that helped to counter a waning of the emotional force of Nazi ideology after the seizure of power; and most important, it surmounted the ideological conflict between technical advances and Nazi ideology.”

Jeffrey Herf (ibid)

The massive propaganda serving to add ‘soul’ to AI as well, or more, to new Green Capitalism, is only echoing National Socialism, really. The question of consciousness (and even much of the debate around animal intelligence) is framed by the influence of authoritarian German ideology circa the 1930s. The questions themselves are wrong. The ideological content is superficially different, just as Biden is superficially different than Trump or Clinton or Sanders. But the form and deeper meaning, is not.

Herbert List, photography.

The idea of inner speech, as it was raised by Godfrey-Smith is deserving a good deal more analysis than I am giving it here. For one thing, there are different kinds of inner speech. In contemporary life the inner voice is cluttered with a good deal of chatter. In fact ever since the Industrial Revolution our inner voices have tended to be cluttered. Buddhist meditation is partly a strategy to quiet that clutter or chatter. I think artists, after a while, if they are any good, find their own forms of quieting the chatter. All mimetic engagement (or nearly all) has a quality of quieting. The current habituation to screens and digital technology is anti-quieting. And there are significant issues in how this affects children.

Schizophrenics no doubt have lost purchase on these inner voices. For truth is, we all hear voices.

“No one knows how old human language is—perhaps half a million years old, perhaps less—and there’s much debate about how it evolved from simpler forms of communication. However language arose, its appearance changed the course of human evolution. By some path that we can presently only speculate about, language was also internalized; it became part of the machinery of thought. This internalization—Vygotsky’s transition—was also an important evolutionary event.”

Peter Godfrey-Smith (ibid)

There are countless theories of human consciousness. How it evolved. And all of those involved readily admit none of them are satisfactory. I think there is something very crucial in Vygotsky’s ideas on inner speech. And there are elements of ‘broadcast space’ theory that seem congruent with this, too. But my point here is that humanity is losing the ability for inner speech. It has also lost, obviously, an ability for speech period. The erasure of the human, for me, means the erasing of language to some extent, but more critically, the loss of those tiers or registers of inner speech. And the ‘space’ we create for our thoughts. And this ties into psychoanalytic theories of trauma, too. But contemporary obsessions of technological progress (computer or AI) is serving to suffocate what is left. It is replacing inner speech with canned speech. And humans are now working with pre-recorded voices in a sense. And the problem is political, of course. For the owners of the screens are composing our inner monologues now. They may not even, often, consciously themselves see it that way. It doesn’t matter. The fake soul in the techne of National Socialism was the precursor. Gates and Musk and Bezos and Zukerberg are none of them particularly visionary thinkers. They are rich, by cunning or luck or inheritance, doesn’t matter. And the clerks to these high net worth figures are no more ethical than Eichmann, actually.

Nautilus shell, by Edward Fielding.

To donate to this blog (and to Aesthetic Resistance, at Soundcloud here https://soundcloud.com/aestheticresistance

use the pay pal button at the top of this page. As always, it is much appreciated.

Hi John,

I recently discovered your work through the essay “Morning in Hell” which was widely shared. It’s such a delight to find voices like yours! I find it really hard to dig through the cacophony on the internet and to find interesting writing. I’ve been reading a bunch of your archives.

I have a question. I am particularly interested in criticism of the technology entertainment complex (the sensorium / the fast paced screen / etc) and it’s a relief to see you weave these elements in with your thinking. Most analysis just ignores it! So I am wondering if you could recommend some of your favorite writing on the topic and some other reads that might help expand my understanding.

Much appreciated, and thanks for the brilliant work.

comment from calla churchward “There are countless theories (the development of two nervous systems in a single body — a light sensing top system and an eating system, and they migrated toward each other until they began to cooperate)…but all these theories are only descriptive, they suggest how it happened, maybe, but not why and nobody has much of a timeline for this stuff. How long did those nervous system migrations take? Ten million years? Twenty? Who knows. Or was it sudden? Did there appear one freak generation of clam?”

Around the 60’s and 70’s, scientists ,experimental physicists, theoretical physicists and mathematicians in a variety of disciplines were (often independently) studying and discovering some mysterious patterns arising in data: a seeming order arising from what looked like randomness or chaotic mess. These explorations into things like “fractals,” and “strange attractors,” which became key concepts in what became to be known as chaos theory. Without going into the whole history of chaos theory here, one interesting observation made by the James Glieck in his history of Chaos, is that chaos revealed the limitations of reductionism, which had become the hallmark of scientific inquiry in the modern day west. Reductionism (in my opinion) is a very political choice of engaging with the world and creating knowledge. It seems to me that reductionism creates a framework of understanding phenomena in a “control” or “means to an end” value system and is a rather safe way of understanding the world. Chaos was the study of something mysterious–the messes, the infinities, the unsolvable equations.

The study of chaotic systems did, in fact, end up being “useful” for western scientists while also challenging a lot of reductionist paradigms. Curiously, as Gleick observes, of all the scientific disciplines, reductionism “triumphed” in biology, and this, he links to Charles Darwin and his theories of evolution that focus on something called “Final cause.” In science, when we ask: What is the cause of this phenomenon? There are two different categories of cause we may be looking at (sometimes they are tricky to differentiate). These causes are “final cause’ and “physical cause.” Final cause is a trait that is formed the way it is for a purpose–something looks/functions the way it does because it fulfills a design or purpose, Gleick’s example being that a wheel is round because it makes transport possible. Physical cause is when a phenomenon has a particular attribute because of the physical forces acting on it, Gleick’s example being that earth is round because that is the form a fluid takes when it is spinning under the force of gravity. Most sciences, when asking what causes something, are looking at physical cause; however, biology and medicine and evolutionary biology tend to focus on final cause. This, as Gleick describes it, has an underlying “teleological” framework–the idea is that, to use a simplistic example, birds have sharp beaks to peck insects and eat (final cause), assuming some sort of purpose or design and there was little consideration of the physical cause underlying this biological structures; I ask: what if, much like gravity pulling the earth into a sphere, there are physical forces that cause bird beaks to be sharp/pointy?

Based on my understanding of chaos theory, it makes sense to ask: what are the physical causes? In terms of some of the questions you pose above wondering “why” did particular evolutionary trajectories happen and “how long” did they take, it seems to me that chaos is a framework from which it is easier to ask these questions and see possible answers and patterns arising. What chaos science does is it studies forms “in motion”…in time, not as static entities. Chaos theory also shows how it is that a fluid sea rolling with different cells and charges and organisms could produce vast and complex life forms. (sure that is a “how” like you said above, but I think the “why” is embedded in chaos theory in the ‘strange attractor’ or the pattern or regularity or ‘home base’ that seems to emerge when we look at an otherwise messy seeming data set and this has something to do with physical cause).

Another way of looking at it is leaf shape. Gleick points out that the shape of leaves. What is the evolutionary purpose of leaf shape? Much pondering over this has led to the conclusion that the shape of leaves is not caused by functionality. Another curious this is that, although there may be differences, leaves are kind of all the same general shape. The details are different, but it truly is a bit Platonic: all leaves seem to follow a rough pattern of some quintessential, universal LEAF. This, can be explored by considering physical cause.

I think what makes this so political and curious is that I see an association between the study of biology and life forms as primarily operating for some sort of purpose, whereas in chemistry and physics, let’s say, we’ve got a focus on forces and physical shapes operating as they do because they HAVE TO as they arise from physical forces like gravity. It seems both strands of science require slightly different narrative frameworks when perceiving their subjects of inquiry. I can’t say i’m an expert in anyway on chaos theory but I immediately thought of the passage of this book when I read this post and the questions you pose about “why” and “how long/when?” kind of seemed accessible to me when I thought back to some of what I read in the chaos theory book. It could have been sudden or it could have taken thousands of years as far as i understand….does it matter? It just doesn’t seem to be an approach that is taken so much by biologists despite chaos having become a bit more cross-disciplinary and fashionable over the years…

chaos science puts the mystery back into certainty and brings contradictions together in a way that can only begin to make sense if one unravels one’s reductionist, individualistic/competitive mindset. Why indeed.

Last Days in the Bad Boys Bunker & Calling All Hands

The uberreal orange nightmare that has most

grimly assaulted our consciousness & our

dwellings must be removed, by any means required.

Please read Paul Street’s urgent article on cp

today https://www.counterpunch.org/2020/11/16/this-regime-must-go-now-three-reasons/

Regino

In all the considerations above it would be very helpful and illuminating to seriously study the concepts of Irreducible Complexity and Intelligent Design:

https://evolutionnews.org/2018/10/behes-irreducible-complexity-validated-by-chemistry-nobel/

https://intelligentdesign.org/