Kon Trubkovich

“It is not how things are in the world that is mystical, but that it exists.”

Wittgenstein (Tractatus)

“Be not rash with your mouth, nor let your heart be hasty to utter a word before God, for God is in heaven and you are on earth. Therefore let your words be few”

Ecclesiastes 5:2

“The criteria distinguishing history from poetics involved the modes of representation, which (if we might exaggerate somewhat) were intended to articulate either being or appearance. “

Reinhart Koselleck (Futures Past; On the Semantics of Historical Time)

“The greatest enemy of knowledge is not ignorance, it is the illusion of knowledge.”

Daniel Boorstin

Many years ago I was reading a lot of Wittgenstein and I remember coming to the conclusion that Wittgenstein was really a Buddhist or Sufi. I remember being laughed at that for that idea. But thinking today about Wittgenstein makes me think I was likely pretty much correct. Now Wittgenstein is a very good antidote to Heidegger. When Heidegger writes of daily language, chit chat or chatter, covering over experience, he is mystifying something Wittgenstein took apart very carefully.

There is a letter from Bertrand Russell to Lady Ottoline Morrell from 1919 after Russell had visited with Wittgenstein and discussed the Tractatus.

“He { Wittgenstein} has penetrated deep into mystical ways of thought and feeling, but I think (though he wouldn’t agree) that what he likes best in mysticism is its power to make him stop thinking.”

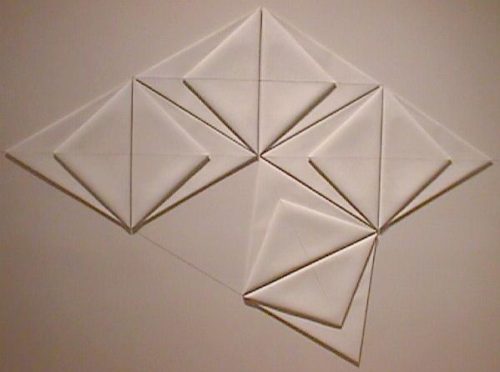

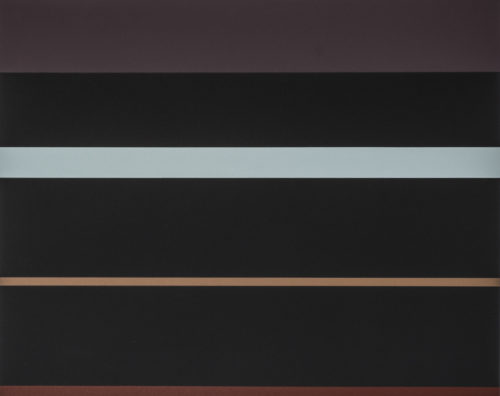

Dorthea Rockburne

Wittgenstein’s ideas on our alienation from language (and alienation is not quite the right word) is not unlike reification or social alienation. What Wittgenstein suggests in the Tractatus, anyway, is that human language creates pictures of the world. Or of *a* world. Now, in most religions there exists an ineffable. In many this ineffable-ness is tied in with the word, with name and never with image, of course. How that relates to Wittgenstein is interesting. In Hinduism, Daoism, Sikhism, and Advaita Vedānta the divine is an original cause, but it is also, in some of those, and in Muslim mysticism, a radical unity. But it is still undefinable. The Dionysian God is the cause of all things through his divine names. It is similar in Sikhism…

“As the primal being willed, Nanak the devotee was ushered into the divine presence. Then

a cup filled with ambrosia (amrita) was given him with the command, “Nanak, this is the

cup of name-adoration. Drink it… I am with you and I do bless and exalt you.”

Guru Granth Sahib (tr.Nikky-Guninder Kaur Singh)

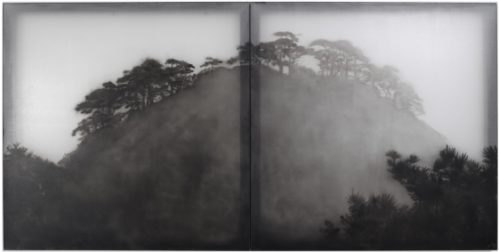

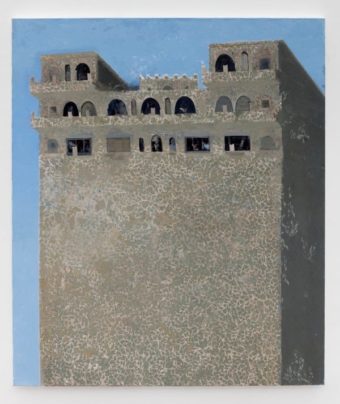

Xie Fan

That I believe religion followed out of theatre is implied in discussion of ineffability in religion. And it is also, naturally, an aspect of devotional silence. With Wittgenstein the logic(s) of language (the structure of language) serve to provide pictures of a sort. The first sentence of the Tractatus is that the world is made up of facts. Not things, but facts. And facts, or, really, propositions, give us a picture of the world (the picture theory in Wittgensteinian studies). These genuine empirical propositions function to depict the world, the state of affairs (Wittgenstein’s phrase) of the real world. This is really about logic, the logic of language, or linguistic structure. Now as a quick digression, this touches on Lacan, too, who looked at Freud and said all that Freud said is true, only it is really about structure and language (the unconscious is structured like a language he famously put it). For Lacan the theories of Freud were explanations of how humans are born into and learn speech and writing. Now it’s not really that simple, but the point here is that what we say matters more and reveals more than what we *want* to say or intend to say or think we are saying. And this is because desire is already baked into this structure that is language. We are, in a sense (!) born alienated, and alienated via language. It is operative in speech. But Lacan in this sense is like Wittgenstein because neither looks to find some romantic notion of authentic expression (like Heidegger did). The authentic is not buried in some remote crevice of our psyche. Nor is it some primal level of pan psychic truth. As Adorno pointed out, Heidegger was looking for a subjectivity untouched by reification.

But to return to the Tractatus; there is a disputed reading here, though I think it is clearly correct, that goes something like logic and language cannot express something that is beyond the world –the world being that which is depicted by language and logic. But there is something true ‘out there’ which, if one could find the tools to express it or even point toward it, would be true. In a sense this is the ineffable.

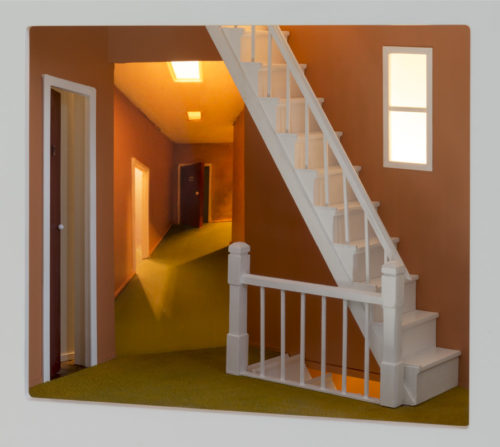

Susan Leopold

Now, theatre, and perhaps even prose in a different sense, are looking for inspiration (a word I don’t like) and then interrogating that impulse. THAT is what writers do. The writing may be slow or quick, it makes no difference. But it is the second and third and fourth guessing that makes for that strange depersonalization that most good writers experience. One often feels as if channelling someone else. The words are not mine, you think. Well, because in one sense they aren’t — but it is only by reaching the point where they are not your words that they truly become your words. Or become the words of the play. And this is because that speech (and maybe those words, scratched on a page…not sure if this is part of where computer writing changed things, and typewriters before that) is, when reflected upon, becomes an echo of some part of your early mental development. All theatre is about, on one level, your own mental origins and earliest trauma. In the same way, I think, that Freud is always partly about language. It is also what Wittgenstein sort of instinctively understood about words. In theatre there is also the space, the stage of that originary conflict or split or lack — that is where theatre begins.

And it is worth considering religions and the early writing from those religions, and how they are extensions of theatre in a sense. And that sounds funny I suppose, but it is also to be noted that there is an implicit political critique that comes out of many early sacred texts. Political in the sense that social alienation and the erosion of language skills means that repression has taken new forms and with new effects. Religion followed upon or came out of theatre. The Ur-theatre is likely just simple small groupings with a central character in the center, on *stage*. Or two characters on stage. And an offstage event or voice. And what is being recited in this *space* is the about who that character is. Existential theatre by way of hunting anecdotes (or dreams). And recitation becomes a huge aspect of repression moving forward.

Side bar: What did cavemen dream? (that’s sort of rhetorical).

“When a dream is interpreted we might say that it is fitted into a context in which it ceases to be puzzling. In a sense the dreamer re-dreams his dream in surroundings such that its aspect changes… In considering what a dream is, it is important to consider what happens to it, the way its aspect changes when it is brought into relation with other things remembered, for instance.”

Wittgenstein (Lectures and Conversations on Aesthetics, Psychology and Religious Belief)

The above quote is not unlike what creative writing does. Or how it does what it does. Except the *surroundings* remain subjective. Usually, anyway.

Hans Aarsman, photography.

There is probably an interesting discussion to be had about the relationship between the uncanny and the ineffable. They are a bit like the inside out of each other. The ineffable is the unforgotten uncanny perhaps. But the ineffable is not disturbing. Not connected to anxiety.

“Nevertheless, the shunting aside of the uncanny by most ‘scholarly’ discourse and research doesn’t succeed in putting it to rest. Rather, like the Sandman, the uncanny crops up again and again, with surprising resilience, where it is least expected: as a figure of speech, an atmosphere of a story, an allegorical instance. Announced by the sound of approaching steps, of heavy breathing, wheezing or coughing, or other semi-articulate sounds, uncanny figures and situations return to remind us of the difficulty of distinguishing clearly between language and reality, between feelings and situations, between what we know and what we ignore.”

Samuel Weber (The Sideshow, or: Remarks on a Canny Moment, 1973)

Weber rightly focuses on reading. As Susan Bernstein writes…“This insistence on reading, foregrounding the textuality of the uncanny, points to the ways in which the uncanny functions as a critique of identity.” (It Walks; The Ambulatory Uncanny) This sort of returns us to Wittgenstein and the ineffable. In the introduction to Philosophical Investigations Wittgenstein observed his inability to put his thoughts into an uninterrupted order. He compared his writing to a kind of album. One critic (I forget who) said is a kind of cubism. In a sense this is one of Wittgenstein’s strengths. His inability (or refusal) to build an analytic whole, a logical progression — though thematically he certainly does this, at least at times. Adorno too refused to write *accessible* texts. Now I am accused often of meandering or digressing infinitely and it’s true. But I believe the insistence on a certain recognized structure is deadly. And I think for playwrights and fiction writers there is a kind of version of this philosophical cubism at work, too. For one must tell a story, a narrative, but one cannot do so at the expense of a search, and this search for what …well, the ineffable? This search is the point. I doubt seriously that Pinter had any idea at all where his plays would lead once he started them. It is interesting in this light to just note that Wittgenstein read very little philosophy. He knew no Kant and little Hegel. He simply wrote what he wrote. He was not a scholar. And hence his writing is never about that anxiety of influence thing that Bloom goes on about. Nor is it remotely what a Walter Benjamin was doing.

Imre Bak

Now, its worth digressing again, or doubling back…and expanding on Adorno’s critique of Heidegger. And in a strange way Heidegger was to mid 20th century thought what Zizek is to 21st century. Both had a pernicious and destructive effect on public intellectual discourse. One of Adorno’s first observations was indirect when he criticized Heidegger’s idea of *historicity*, which term immediately reminds one of truthiness. Adorno’s essay The Idea of Natural History was an indirect response to Heidegger and what Adorno saw as the false reconciliation of Nature and History. And, what Adorno objected to in the invented terms Heidegger was so fond of, an affectation really that served to absolutize Being, while draining it of social content or actual history. Now Heidegger is a curious case in the sense that his writing on the Pre Socratics avoids many of these problems, and I confess to having spent a lot of time with that volume. But when you get to Being and Time it is hard not to be struck by the glaring banality of much of it. Or, not *much* of it, but certainly early in the first part one encounters these oddly simple crude comparisons (and I wonder if Heidegger’s most famous book won’t in fact age very badly?). It is very much worth reading Marcuse, too, on existentialism (mainly Sartre) because the arguments there mirror nearly exactly what Adorno was saying of Heidegger.

Corrado Cagli

But the early Heidegger, the one who wrote on St Paul, and on Christian mysticism, is considerably more interesting, at least insofar as the idea of a pre-Cartesian consciousness experiencing the everyday, and of course *time*, will lead inexorably toward the ineffable. And that will serve as my segue back to mysticism, the uncanny, and Wittgenstein. And Stanley Cavell is right when he says Wittgenstein is hugely important for all subsequent philosophy, and everyone knows this, but nobody quite knows what to do with him.

“Heidegger… cracks the whip when he italicises the auxiliary verb in the sentence, ‘Death is’. The romantic or translation of the imperative into a predication makes the imperative categorical. This imperative does not allow for refusal, since it no longer at all obliges like the Kantian imperative, but describes obedience as a completed fact… The objection raised by reason is banned from the range of what is at all conceivable in society.”.

Adorno (Jargon of Authenticity)

This is an amazingly perceptive take by Adorno. The authoritarian grammar that Heidegger created was serving to polish up his volkish admonitions (also disguised, mostly) about traditional simplicity — an image conjured and made nostalgic once it is removed from any social history. And this is important when examining the writing of Wittgenstein, especially perhaps his very last works. What Heidegger did, and it is largely responsible for his popularity, was to create the appearance of complexity and density by inventing words, jargon, and by developing this faux archaic style and his philosophy is to, say, a Kierkegaard what Game of Thrones is to Geoffrey of Monmouth. Heidegger was not like Zizek in that Heidegger actually could think. What he wrote was philosophy, just an exterminationist and authoritarian philosophy.

It is interesting to observe that the bourgeoisie today have accepted through a kind of necessity to identify more strongly than ever with the ruling class and aristocracy. The bourgeoisie in Europe and North America always felt an irrational sort of attachment to royalty — but it was a kitsch notion of Royalty. Today they have adapted the point of view of those above them in the class hierarchy, and even abandoned their own best interests at times (though that is debatable I guess) to align with the most wealthy and numerically tiny sliver of ruling elite power. The bourgeoisie will increasingly vote for the most elitist of candidates, is my prediction. And this is all to help sustain capitalism. Much like the marketing aspect of global warming is about saving capitalism before all else.

Yutaka Takanashi, photography (Tokyo 1978)

I wrote before about Franco Moretti and Dominique Pestre’s study of financial language essay (http://john-steppling.com/2017/06/the-only-possible-one/)

“To appreciate the novelty, let’s recall that, in the 1950s–60s, issues were studied by experts who surveyed and conducted missions, published reports, assisted, advised and suggested programmes. With the advent of management, the centre of gravity shifts towards focusing, strengthening and implementing; one must monitor, control, audit, rate (Figure 2); ensure that everything is done properly while also helping people to learn from mistakes. The many tools at the manager’s disposal (indicators, instruments, knowledge, expertise, research) enhance effectiveness, efficiency, performance, competitiveness and—it goes without saying—promote innovation.”

Moretti and Pestre (New Left Review)

Here is the link to the entire piece https://newleftreview.org/issues/II92/articles/franco-moretti-dominique-pestre-bankspeak

It is important to examine the language of the new Green capitalists. (See Cory Morningstar’s Wrong Kind of Green). For this is the continuation of bank speak marketing. Words like *commitment* and *dedication* are there again, but used to help the new client, the planet earth. The environment has replaced developing countries as the object of financial largesse and wisdom. And Hemingway’s concrete nouns give way to increasing financial abstraction.

Prabhakar Pachpute

“In the passage from 2008, the terms action and cooperation belong to a class of words usually known as ‘nominalizations’, or ‘derived abstract nouns’; derived, in this case, from verbs: to ‘act’, to ‘cooperate’.footnote8 In English, such terms are recognizable by their typical ending in -tion, -sion and -ment (implementation, extension, development . . . ); so, we extracted from the Reports all the words with such an ending and hand-checked the top 600 (to eliminate ‘station’, ‘cement’, and the like). Figure 7 presents the results. According to corpus linguistics, in academic prose the average frequency of nominalizations derived from verbs is 1.3 per cent. In the World Bank Reports, the frequency is near 3 per cent from the start, with a higher peak around 1950, and it keeps growing, slowly but steadily, plateauing at 4 per cent between 1980 and 2005, and dropping slightly thereafter.”

Moretti & Pestre (ibid)

The new green revolution, the climate rebellion, etc…in fact even the doomsayers, the lap top nihilists who revel in faux despair, are curiously opaque. I read one source who referred in a personal narrative to ‘having spoken to top arctic scientists’, but never identifies them or what they were specifically studying, or who was funding their research. Nothing. And that is because it’s a code, a new green jargon.

You see it with another point that Moretti makes, *singularization*. The singular abstract noun also suggests no alternative, it is a silent coercive. And this is also not unrelated to Heideggerian speak. It is the voice of the fascist political leader as well as the World Bank quarterly report.

“This recurrent transmutation of social forces into abstractions turns the World Bank Reports into strangely metaphysical documents…”

Moretti & Pestre

Refer here to Wittgenstein. For the heart of the Wittgensteian complaint about metaphysics is found exactly in World Bank Reports and the like. The bank report resembles, then, a kind of City of God set of footnotes.

Moretti and Pestre continue….“the authors of Corpus Linguistics continue—in nominalizations, actions and processes are ‘separated from human participants”. And this is, of course, perfect. This is what is happening since the 1980s on multiple levels. The trend is always toward alienation of some sort. Never toward integration or unity. Now integration is often being sold, but it might be worth looking at the distinction between integration and consolidation.

Paul Davies

“In the case of less powerful literatures, then—which means: almost all literatures, inside and outside Europe—the import of foreign novels doesn’t just mean that people read a lot of foreign books; it also means that local writers become uncertain of how to write their own novels. Market forces shape consumption and production too: they exert a pressure on the very form of the novel, giving rise to a genuine morphology of underdevelopment.”

Franco Moretti (Planet Hollywood)

The language of the World Bank and other international financial institutions (and this trickles down to one’s local bank, too) is a language that is both authoritarian, but also anodyne in a sense, too.

Allow me to quote myself from that earlier piece I linked to above:

“If Dracula and Frankenstein arose out of the Industrial Revolution, as somehow also the avatars for a receding mythology of Dionysian disfigurement, the fictional monsters of today are the avatars of financial capital. The age of finance capital seems to be the age of Zombies, or the walking dead. Dracula of course was a venture capitalist in his later incarnations, but of an older order of entrepreneurship . Now the vampire figure is always seen as modern or at least modernist, because it lives forever. Like capital. Like inheritance and interest. Vampires are there to collect the vig.”

Jan Van Eyck (The Ghent Altarpiece: Angel of The Annunciation, detail. 1432)

And a quick side bar. I was asked recently to list my favorite paintings, the ones that most influenced me…regardless of other values or lack thereof. I forgot Van Eyck. If one goes to look at the reproductions somewhere (and in person the Ghent Alterpiece is rather breathtaking in fact) you will see Van Eyck looms as nearly impossible to grasp. His is the art of the impossible.

Ok, back to the issues at hand.

“Dreams do occupy a place at the extremity of a conceivable scale of susceptibility to historical rationalization. Considered rigorously, however, dreams testify to an irresistible facticity of the fictive, and for this reason the historian should not do without them.”

Reinhart Kosseleck (ibid)

Kosseleck describes the dreams recorded from the Nazi camps. The unutterable quality, the dumbness of the dreamer. Noting how Hitler viewed secrecy in three levels. Secrets he shared with his inner circle, then secrets he shared with nobody, and finally secrets he dared not think through completely.

Dora Longo Bahia

“The emergence of new words in the language, their growing frequency of use, and the shifting meaning stamped upon them by prevailing opinion—all that which one can call the currently ruling linguistic fashion—is a not inconsequential hand on time’s clock for all those able to see in seemingly trivial phenomena changes to the real substance of life.”

Wilhelm Schulz (Die Bewegung der Produktion, quoted by Kosseleck, 1841)

Today there is a growing trend in language that reflects both what Adorno wrote of Heidegger, and what Moretti saw in more general terms. And what Wittgenstein was investigating throughout his life. And the trend is evident in Moretti’s piece on the World Bank, and it is evident in the mystified language of so much academic criticism, as well.

“Beginning with the First World War, a process became apparent which continues to this day. Wasn’t it noticeable at the end of the war that men who returned from the battlefield had grown silent—not richer, but poorer in communicable experience?”

Walter Benjamin (The Storyteller)

Moretti then writes “Men had grown silent. They were not “omitting” the details of wartime experiences; they didn’t know how to speak of them. It is against this background that Hemingway’s rhetoric of taciturnity acquires its historical significance: it’s a way of writing that takes the soldiers’ aphasia as his starting point and transforms it from a “curse” into a style.”

(The Far Country)

The Killers (1964, Don Siegel dr. Ronald Reagan in remake of film based on Hemingway story)

This too is related to the World Bank and other corporate speak — where there is an actual awareness that its producer’s living room, or the conference room at corporate headquarters, but where this is endowed with the significance and expanse of the world. So in these culture entertainments or product you see a strange tension at work between what is pretended to be there and how it is not there.

The Hemingwayesque aphasia is now wed to the internalized western hero of few words. Moretti has a fascinating chapter on westerns and film noir. But I will touch on a couple things here, though later I think it would enjoyable to dissect the entirety of this chapter (in The Far Country).

“Conquest: the tempo remains slow, but it has become unyielding. The eyes of the American people, wrote Tocqueville at the onset of the great migration, “are fixed upon [their] own march across these wilds, draining swamps, turning the course of rivers, peopling solitudes, and subduing nature”; they “enjoy dreaming about what will be.” Dreaming … But this is more like an obsession. ”

Moretti (ibid)

George Caleb Bingham, 1850.

The Western is the second act to Moby Dick in a sense. The slow unrelenting march toward domination. Even if ephemeral for most it was the personal narrative built in their heads and rarely shared with others.

“What is distinctively ‘American’ is not necessarily the amount or kind of violence that characterizes our history, but the mythic significance we have assigned to [it], and the political uses to which we put that symbolism.”

Richard Slotkin (Gunfighter Nation)

Moretti quotes Slotkin from a Gunfighter Nation (I named a theatre company I ran Gunfighter Nation, for the record) a book I highly recommend. For anyone not American by birth I think it is hard to understand just how profound is this statement. It permeates the private (and public still) mythology of nearly all Americans.

Whirlpool (Otto Preminger dr. 1949, with Gene Tierney )

“In film noir, one is shot from a few inches away, or with the gun’s barrel touching the body, like Stanwyck in The Strange Love of Martha Ivers (1946), or Mitchum in Out of the Past (1947): an index of these films’ deadly mix of intimacy and treachery. In the Western, shooters are twenty or thirty steps apart; a public dimension, in the town’s main street, at midday.”

Moretti (ibid)

The current series Yellowstone is a fascinating coda to the Western, in a sense. Hugely reactionary it is also very well written, and thematically it is the foreclosed drama of Manifest Destiny, while also foreclosing the mute masculinity of the cowboy. If one just didn’t have to watch Kevin Costner, it would be a rather enjoyable guilty pleasure (Costner has two expressions, and both include his tongue in his cheek. It is almost pathological and disturbing to watch because soon one can’t think of anything else while watching the show). The prose of hardboiled detective fiction was the inversion of Hemingway (and newspaper writers) that turned the conservative repetitions into a new catechism of social alienation. It was the ideological (almost religious) instruction of the unutterable truths of cynicism and nihilism. The form became its own kind of content. Didn’t matter, often, who had committed the murder or crime, it only mattered who would be blamed.

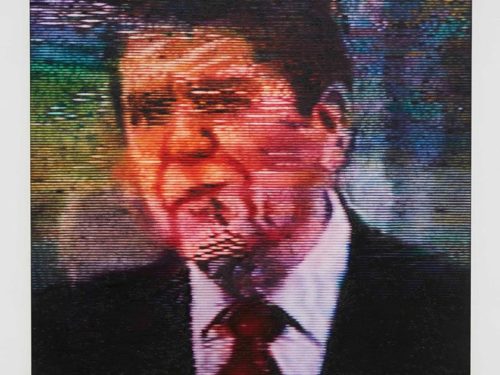

Ronald Reagan, Death Valley Days , TV.

There is then a kind of erasure going on in contemporary culture. History for certain is being erased (and rewritten when necessary) and simultaneously a re-defining of key words and a repurposing of discourse altogether. The nearly hypnotic overwhelming desire for consensus has bled into how words are used, how dialogue is used and more, how it is heard. The fascist techniques of obfuscation are everywhere. The climate discourse I have written of elsewhere (https://www.counterpunch.org/2019/06/26/the-monkeys-face/ ).

Skeptics on climate are the new child molesters. The ultimate outcast. And as a side bar I see the word pedophilia misused even by smart people (confusing it with Ephebophilia or ebephilia, for example). The fascist sensibility is leaking more and more into academic discourse as well, for all subjects. What Adorno saw in Heidegger and what Moretti describes in his World Bank essay is now the style codes for nearly all official and institutional declarations. The deterioration of western culture, meaning mostly in this case American culture, really accelerated around 1980. It was already happening in the 70s certainly, but the 70s is a conflicted and ambivalent decade. The 70s was about killing off the social movements that began in the 60s. By the early 80s there was a sense of teutonic shifts in culture. I only note this here because only a decade later, as societies of the west closed in on the symbolic millennium, the effects of the internet were suddenly profoundly apparent. I think everyone can remember the sudden explosion of texting and the front edges of social media. Facebook began in 2004. Fifteen years later and the world of communication has altered nearly everything of daily life. But what happened throughout the twenty years from 1980 to the start of social media was the utter destruction of education and literacy. The effects have been nearly incalculable. And I think one of the unconscious engines behind the environmental nihilism is actually the inability to face the world created by the new mass communication.

Frank Durbar

Moretti concludes The Far Country with Hopper and Warhol. With Hopper the conservative sensibility of Hemingway is continued. This is not really a pejorative observation. Hopper was also deeply observant and prescient. The sense of isolation and alienation is uncompromising. Warhol is both a departure and not a departure. I think Moretti fails to really grasp Warhol — and I say this knowing its dangerous to disagree with Moretti as he turns out to be right more often than not. But Warhol is an outlier in a sense. Pop Art arrived and while Warhol led that arrival he was also not quite part of it. I’ve noted before that I think Warhol is likely much better than anyone has quite realized and maybe we still cant realize what he was doing. But whatever it was it was not what Lichtenstein or Peter Blake were doing. But the point is that the deep inexorable racist and neo colonialist American dream had stalled, had reached the California beaches and was left with having to turn around and see the wasteland left behind. Moretti notes in the classic Western there is no home. Nobody is returning home because the entire project was to leave home. And yet nobody quite believed they had started a new home. The horrors of genocide and slavery lived on in the American psyche. As the westward movement slowed and finally stopped the horror was internalized and turned on itself, and turned on whoever was available. The ruling class was already creating their new other world. The New World Order. Unions were destroyed and community was erased. The American suburbs were already falling into disrepair. Both material and psychologically. After Reagan, the last great fake frontiersman, the B movie actor who made a half dozen forgettable westerns and who was a pitchman for Twenty Mule Team Borax, the culture was left with nothing to dream or imagine or even desire.

Andy Warhol (Portrait of Ingrid Bergman) 1983

“A few individuals after having long considered themselves experts speaking a scientific language, have finally awoken form their slumbers and suddenly realized that for the last few moments they have been walking on air, like Felix the Cat in the old cartoons, far from scientific ground. Though legitimized by scientific knowledge, their discourse is seen to have been no more than the ordinary language of tactical games between economic powers and

symbolic authorities.”

Michel de Certeau (The Practice of Everyday Life)

“These ancient authors introduce into our present-day world the language of a “nostalgia” in relation to that other country. There they create and maintain a place for something like the Brazilian saudade , a homesickness—if it is true that this other country also remains our own, but we are separated from it. { } I, like Kafka’s “man from the country,” asked them to let me enter. At first, the doorkeeper would answer, “It is possible, but not at the moment.” After twenty years of waiting “near the door,” I have come to know, “by examining him,” the appointed keeper of the threshold down to the least details, “even the fleas in his fur collar.” So it has been with my guardian Jean-Joseph Surin and many others—more than a match for my most patient erudition—whose texts never ceased peering down upon my search. Again, Kafka’s doorkeeper says, “I am only the least of the doorkeepers. From hall to hall there is one door¬ keeper after another, each more powerful than the last. The third doorkeeper is already so terrible that even I cannot bear to look at him.”

Michel de Certeau (The Mystic Fable)

Edi Hila

Western culture has lost the idea of the ineffable even as society lives ever more in a alienated state detached from the world. Moretti sees the Western and film noir as parallel yet opposites. What he fails to note is that noir was invested in paranoia. In social distrust and a dread of authority. The western was never paranoid (well, not never, Man of the West, Anthony Mann’s 1958 film, is both paranoid and a uniquely anti-Western for its time). The Western believed in society. It may have been realistic about authority, about its failings, but the western protagonist never doubted that criminality was to be stomped out, and to at least try to knit together the social fabric.

The soldiers return from the first world war, the unutterable, the impossible that became therapeutic omissions, the secret Hitler could not look at, the doorkeeper’s doorkeeper too terrible to gaze upon; these are threads of something ineffable.

“For Daoists, at least for members of the classical Daoist inner cultivation lineages and those with similar affinities and aspirations, the elders and models documented in the Book of Master Zhuang suggest that there are transformed existential modes beyond conceptualization and intellectualism, beyond thinking and knowing. Transformed through contemplative practice and introvertive mystical experience, in such a state of being and form of extrovertive mysticism, one may find ways to speak the unspeakable.”

Louis Komjathy (Names Are the Guest of Reality: Apophasis, Mysticism, & Soteriology in Daoist Perspective)

Jill Paz

To donate to this blog just use the paypal button at the top. Thanks to those who have and those who might. It is hugely appreciated.

Per John Berger, they dreamt of animals:

“The need for companionship while alive was the same. The Cro-Magnon reply, however, to the first and perennial human question, “Where are we?” was different from ours. The nomads were acutely aware of being a minority overwhelmingly outnumbered by animals. They had been born, not on to a planet, but into animal life. They were not animal keepers: animals were the keepers of the world and of the universe around them, which never stopped. Beyond every horizon were more animals.”

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2002/oct/12/art.artsfeatures3

that’s just a splendid little piece by Berger. Very moving. Twenty thousand years and today there is burn out at three or four.

from Molly Klein…having trouble with my endlessly irritating comment mechanism.

”

“Great post.

I keep thinking about that Moretti essay on World Bank langauge also.

HE really is the best Marxist lit critic of the postwar. He didnt just ignore the posties but he didnt concede to the power of fashion and the establishment. He also has great taste. I only realized recently he is the broher of Nanni Moretti. There is a touching and beauridully acted and kind of evil antocpmmie movie by NM called My Mother that seems to be the bourgeois pseudoaesthete pseudoartist triumphant scourging the defeated Marxist sibling (who is not Franco but a female movie direftor with a brechtian and commie bent who is sort of the fantasy figure ofntje director Nanni thinks Franco thinks Nanni ought have been). Turturro is in it, not the lead, and does a remarkable subtle magical thing. BUt the movie is really reactionary in a scary condescending way. Curiouas about whether you’ve seen it.

I think John also you would love this noevl by Kim Stanley Robinston called _Shaman_ about those Cro-Magnon. IT’s genre pulp but it’s absolutely sincere and unlike the caveman adventure genre generally totally commie anthropology not fascist and creepy, and its also about the aesthetic (in I suppose the romantic sense of play) foundations of humanity per se”

Great piece, John..altho’ as per usual I really only feel I understand half of what you’ve written. Your essays – at least for me – require re-reading and have always been well worth it.

I’m interested in what you mean by your comment that Van Eyck’s “was the art of the impossible”

Acute, accurate, piercing, brilliant, important and for me extremely educational. I always look up words, concepts and this piece deserves a standing ovation. It touches so many areas (theater, politics, psychology, philopsopy, past and present literature, memes, the importance of awareness, consciousness, correct interpretation of world events and the power players domestically and globally. As an amateur and a student I am sure better praise could be written but I don’t have the intellect or words but do have an innate ability to grasp the ineffable and show it for what it is and to reject the anodyne .