Sarah McCoubrey

“That is, medicine has been (and continues to be) an important social institution for reasons other than its ability to heal.”

Jacob Stegenga (Medical Nihilism)

“Though the doctors treated him, let his blood, and gave him medications to drink, he nevertheless recovered.”

Leo Tolstoy (War and Peace)

“Eunuchs do not take the gout, nor become bald.”

Hippocrates & Galen (Galen)

“Crazy as two waltzing mice.”

Raymond Chandler (Farewell My Lovely)

Discussing health and illness is fraught with contradictions and confusions. Almost any definition of disease relies on certain notions of normalcy, or functionality. To call a condition, say depression, dysfunctional becomes a circular argument at a certain point. Does one want to “function normally” in a society of irrationality and acute inequality? The fact that today there are statistical spikes in depression among teenagers begs all sorts of questions.

“Claiming that diseases must have a biological basis would be too strong because there might be some mental diseases where there is nothing wrong with the patient’s brain. It might turn out, for example, that irrational phobias are completely indistinguishable from reasonable fears by the neurosciences.”

R. Cooper ( Disease. Studies in the History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences, 2002)

But there is more than just the inability to define psychiatric conditions or diseases. And this relates to aesthetics, too, in a roundabout way. Or rather, there is an aesthetic question that lurks on the periphery of societal questions of mental health, and more, of normalcy.

Hon Chi Fun

“For madness, like sleep, is assumed to be a twin of death, a darkening or dampening of the (rational) soul that deprives the soul of its most essential feature, its lucidity; yet, also like sleep, it is assumed to be a wakening, a rising into the fresh yet ancient reality of the dream”

Louis Sass (Madness and modernism: Insanity in the light of Modern art, Literature, and Thought).

Once culture is drained of reality, of material existence, ideas of adjustment and normalcy are only abstractions. The notion of madness, for the last, say, three hundred years is related to a certain mythology — Sass notes…“ the truly insane, it is nearly always assumed, are those who have failed to attain, or else have lapsed or retreated from, the higher levels of mental life. Nearly always insanity involves a shift from human to animal, from culture to nature, from thought to emotion, from maturity to the infantile and the archaic. ” Looked at on a societal level, there is something here that links to the dialectic of enlightenment.

There has been, at least since the Industrial revolution, an incessant desire to somehow define and quantify insanity (far more than defining sanity). And there is always, too, a romanticism (perhaps beginning with the German Romantics) that says the Dionysian is a form of Holy Madness, an insight and not a retreat. But all of these models run into problems with how to find the normal, the baseline as it were, for feelings of dysfunction or alienation.

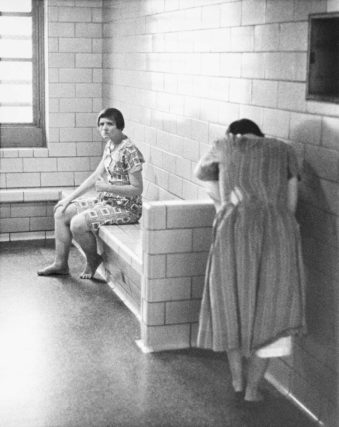

Dunning Mental Hospital, Chicago 1947.

“The movement of ideas and political institutions has rendered once immovable and stable occupations subject to change…. Many minds, over-stimulated by a headlong and unlimited

ambition, having worn themselves out, perverted in a struggle beyond their strength [end] up in madness…”

Henri Girard de Cailleux, director of the asylum at Auxerre, France 1846

The schizophrenic has become a sort of short hand mythology all unto itself. { Deleuze and Guattari helped that idea along, certainly.} And today, in other ways, autism is doing much the same thing. The very idea of adjustment is so pernicious and insidious as to defy all logic. But here one encounters this notion of reason, again. The idea of this mental agility that separates us from animals (or for many, from other humans who are of the wrong religion or skin color). Capitalism has bred a monopoly framework in which actual social mobility is acutely restricted, even as it is widely advertised. A framework in which promises exist as the backdrop for all of daily life. The drive for success or fame always is played out in one’s mental theatre with a cyclorama made up of promises. What images are tied to promises?

August Sander, photography (Young teacher, 1928).

“The problem of our natural inclination to read backward into the past from the perspective of the present also extends to speculations concerning whether mental disorders that we now diagnose as schizophrenia are of recent origin (perhaps as “diseases of civilization”) or existed hundreds or even thousands of years ago. Arguments can and have been made for and against this recency hypothesis. Then of course there is the issue of Western ethnocentrism and the cultural bias inherent in any attempt to see current Western conceptions of mental disorder in non- Western cultures of the present or the past.”

Richard Noll (American Madness)

In a system of such coercive conformity — an issue that isn’t discussed or focused on nearly enough — the idea of mental disorders (insanity, madness) should be viewed firstly in terms of the anxiety and fear of non conformity, the perception of self as non conforming. The pharmaceutical industry is predicated on controlling non conformity — of pathologizing it and shaping the perception of it. The fact that ‘madness’ as a word is no longer in use speaks to this. The faux medical terminology and treatment is all geared to eliminating the perceived threat of those who’s economic (usually though hardly always) background hinders their ability to conform. And this conformity is an intellectual exercise in amnesia and self erasure.

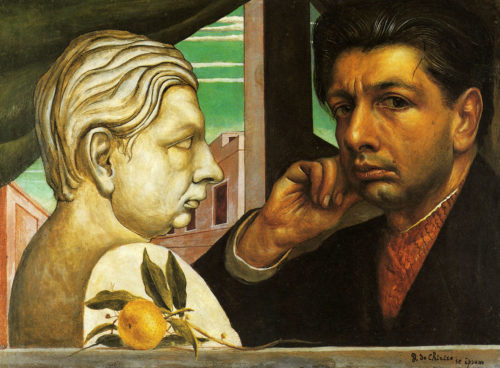

Giorgio De Chirico, self portrait, 1922.

“The colonists not only mystify the natives, in the ways that Fanon so clearly shows, they have to mystify themselves. We in Europe and North America are the colonists, and in order to sustain our amazing images of ourselves as God’s gift to the vast majority of the starving human species, we have to interiorize our violence upon ourselves and our children and to employ the rhetoric of morality to describe this process.”

R.D. Laing (The Politics of Experience)

I’ve written before about the de-politicizing of psychoanalysis as it migrated to the U.S. Everything radical, politically, in that first generation of Vienna based Psychoanalysts was erased. And in essence, psychoanalysis became adjustment therapy. Russell Jacoby wrote about this best in several of his books. But another aspect of this de-politicizing was the shift away from discussions of nerves and a shift toward mood, toward depression. As Edward Shorter writes…“The analysts were interested in affect; they were not interested in fatigue, insomnia, or any of the rest of the nervous syndrome.”

One of the problems with Shorter’s book (How Everyone Became Depressed) is not that he is not correct about changes in psychiatry when it appeared in North America, but that he seems not understand why depression, actual depression, might not be epidemic in the West today. The difficulty here is that Shorter is also quite right about the role and influence of big Pharma. The pharmaceutical industry all but directs the diagnostic terms for today’s mental health practitioners. Couple that (which Shorter under emphasizes) to the loss of what those early Psychoanalysts were saying, and one ends up with a pseudo science of domination and chemical warehousing.

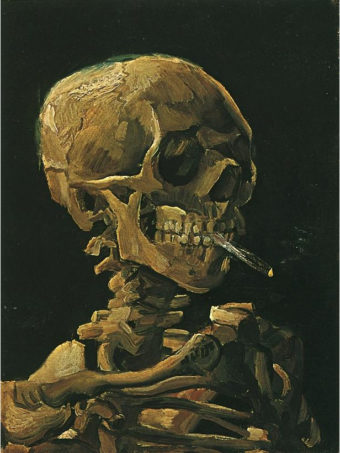

Vincent Van Gogh

Notwithstanding this:

“A depression needed to be created that could be applied to everyone. The drafters of the third edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) DSM series did this in 1980 by

creating major depression. { } Of the unitary diagnosis of nerves, a disease of the entire body, nothing was left except major depression, an expandable diagnosis that could be applied to

almost the entire population—and a series of mini-anxiety diagnoses pseudo specific for different settings in which anxiety might arise: parties (social anxiety disorder), trauma (post traumatic stress disorder), public places (agoraphobia), and so forth. The shattering of the nervous syndrome was complete.”

Edward Shorter (How did Everyone Become Depressed)

And this is exactly true. However, this has nothing to do with the validity of the idea of repression.

William Adolphe Bouguereau, 1852. (Dante and Virgil in Hell)

There has been a clear fashion (and profit margin) in drug usage, and prescription. Truth is, cocaine as it was used in “women’s” remedies, and various opiates, were highly effective at treating fatigue and anxiety. And opiates in a certain context are the greatest anti depressant ever imagined. Today though, the pharmaceutical industry is pushing not just drugs, but a world view. An existential framework out of which doctors feel, themselves, coerced to prescribe whatever the latest generation of antidepressant, or mood elevator. This world view is one in which the past is, for the most part, erased. The present is narrowed and emphasis in place on communication and results. And results means being better at your job. And being better at your job, in this context, means not making waves. Labor organizing is NOT being better at your job.

But even “radical” psychoanalysts like Laing and Cooper run into some of the same problems one finds in all the post Freudians (in the US) and certainly in the neuroscience professionals. And the biggest problem is, finally, a kind of superficiality. The deep dark and usually hidden trauma, and attendant myths, that Freud and Fenichel and Ferenzi were after give way to a results oriented exercise that applauds the communicative as a principle of health of the highest order. And one sees the reflection of this in theatre or film these days (and prose for that matter) in which communication, as a given, and as a goal, is affirmed — no matter how superficial.

Christopher Hanlon

The infantilization of narrative and the loss of history (or the substitution of a fake history) prevents the uncanny, prevents allegory — and so much of this trend is reinforced with a model of human health that is aligned with communication, agreement, optimism, progress, and a manufacturing of an idea of happiness that coincides with having one’s life “work”…a life where things fit and make sense.

“DSM-III was big. It gave psychiatry a public profile much larger than ever before, and attuned people to psychiatric diagnosis as a kind of normal event, much like any other illness, rather than as some nightmarish visitation. But the line between the beneficial destigmatization of illness and the epidemic spread of an illness attribution is a thin one. At some point, medicine stops and culture takes over. Spitzer agreed subsequently with an interviewer that DSM-III and its successors had become “cultural events.” “It is amazing. I guess it defines things. . . . I guess it defines what is the reality.”

Edward Shorter (How Did Everyone Become Depressed)

After 1980, Shorter notes, there was a homogenization of the idea of depression. Firstly, what was previously called melancholia was subsumed under this generalized idea of depression. And by the definitions of the DSM nearly half the population was at one point depressed. The fall out from this in psychiatry was huge, but culturally it was perhaps even more significant. The praise for removing the stigma of needing therapy was replaced by a meaningless subjectivity that suggested all discomforts were self induced …but no worry, they can be quickly treated with, almost always, drugs. The culture of self help and personal responsibility embraced the idea of a world without melancholy. (Actually melancholy was reintroduced to the DSM, but in attenuated form, and in a sense what went missing was the very idea of a psychic pain deep enough to be debilitating and causing massive change in bodily function). This is all a part of the great fabric of cheapening experience. And since experience still occurs, however accidentally or adumbrated, the tendency is to then lie about it. And art and culture again reflect this.

Richard Avedon, photography (East LA mental hospital, 1963).

This is an interesting aspect of all of above, and it ties into today what is a clear rehabilitating of fascism.

“In Nazi Germany paediatric psychiatrists served as consultants to youth groups, welfare offices and schools. It was the form their ‘national service’ took. They tracked subjects through childhood, shaped what was considered normal behaviour, and identified and codified what was not. Ernst Illing claimed that he could make a call about a child at the age of three or four – he could spot what he called ‘Gemüt poverty’. Gemüt meant ‘soul’ or ‘spirit’, but also gestured to a person’s capacity for tribal belonging: for feeling and emoting spirit, as in national or school spirit; and for social competence. None of these meanings was new, but how ‘Gemüt’ came to matter was. Gemüt-poverty was a medico-spiritual diagnosis that could send children to their death at a place like Spiegelgrund, a children’s killing centre in the outskirts of the Vienna Woods, part of the Steinhof mental hospital. Illing was the medical director of Spiegelgrund from 1942 till 1945. One of his predecessors was Erwin Jekelius, who claimed to have an aptitude for spotting teenagers with poor Gemüt. And he was a close associate of Hans Asperger, who developed a new label for classifying children, ‘autistic psychopathy’, which he couched in terms of poor or absent Gemüt (‘a qualitative otherness, a disharmony of feeling’), diagnosing them with ‘unfeeling malice’.”

Michele Pridmore-Brown (London Review of Books, 2019)

Chole Piene

Asperger’s work was rediscovered in the U.S. over last twenty years. And it has led to a pop culture embrace (and into pop grammar) of autism as it is being discussed now by neuroscience and brain imaging. The *spectrum* idea has been widely accepted and is embedded now in US popular culture. Pridmore-Brown is reviewing Edith Sheffer’s book Asperger’s Children– she summarises thusly….“Sheffer argues in Asperger’s Children that, regardless of the science, and regardless of whether autism is one condition or several, it remains steeped in the cultural values of its Nazi origins, and in the idea of a model personality: obedient, animated by collective bonds, socially competent, robust in mind and body.”

That Asperger’s research and practice should prove amenable to contemporary American sciences and health care is very telling, I think. For this is a man who a bit later in life was quite comfortable with Nazi experiments on children deemed unfit to live.

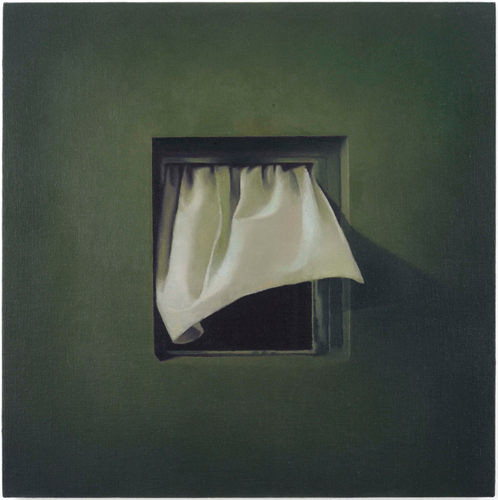

Gotz Diergarten, photography.

“Asperger’s diagnosis remained little known for decades, until leading British psychiatrist Lorna Wing discovered Asperger’s 1944 thesis and publicized the diagnosis in 1981 as “Asperger’s syndrome.” The idea took off in psychiatric circles and, by 1994, the American Psychiatric Association included Asperger’s disorder as a diagnosis in the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV). Because Asperger’s disorder has been increasingly understood as “high-functioning” autism, the American Psychiatric Association removed it from the DSM-V in 2013 and subsumed it under the general diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder. But internationally, Asperger’s syndrome remains a distinct diagnosis in the World Health Organization’s predominant standard, the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision”

Edith Sheffer (Asperger’s Children).

Nazi psychiatry depended on mass surveilling of subjects, and with a clear model for the healthy Volksgemeinschaft….the community of the Reich. Autism provides a rather singular symptomatology in respect of conformity and nativist fascist movements — for the autistic individual is about the least likely person to ever feel the pull of that simplistic tribal scapegoating — the autistic is preternaturally isolated and within a certain framework, comfortable not joining much of anything. These are solitary individuals, impervious, largely, to most mass propagandizing, and in a sense disobedient overall. At least from the perspective of the crowd or the authority structure.

“Eugenicist ideas were in circulation in the 1920s and earlier, long before the Nazis; the theory and practice of forced sterilisation was imported from the US and continued there after the war. Nazi psychiatry did not arise out of nothing, and it hasn’t been tidily buried. Thirty diagnoses created under the Third Reich are still in use today, created against the idea of a ‘model personality’.”

Michel Pridmore-Brown (London Review)

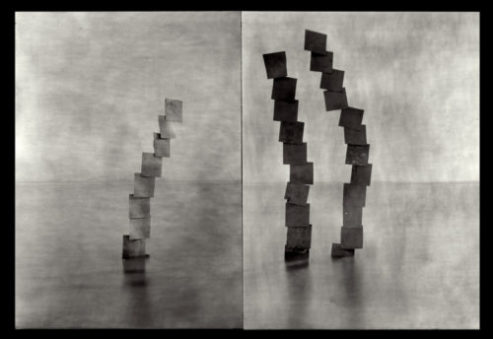

Richard Long

Now I think that the entire spectrum idea is deeply flawed. Today the “aspie” is a proud sub group with clear identity markers and an insistence on special abilities that “neurotypicals” don’t have. The non high functioning autistic is another story altogether. And one that entails a good deal of suffering and commands a good deal of help from the medical world. And I am hardly in any way an expert on autism. The salient point here is one that Sheffer makes in her book — National Socialism and Aspergers (or autism overall) are the inverse of each other.

“The diagnosis did not arise fully formed, sui generis, but emerged bit by bit, shaped by the values and interactions of psychiatry, state, and society.”

Edith Sheffer (Asperger’s Children).

The discovery and diagnosis of what has come to be called Aspergers Syndrome was an emergent set of properties that stood in stark contrast to the mass conformity and unnatural seduction by authority found in Nazi culture. The contrast, however, is also easy enough to find in U.S. society and culture. And it is perhaps this linkage to the logic of eugenics that is so disturbing, somehow.

Ed Ruscha

I wanted a short aside here to quote something indirectly related, but something that I’ve touched on several times on this blog. And that is the idea of pre modern thought and, really, what it might have looked like.

“Most of us know about subliminal awareness–the type of awareness lurking below actual consciousness that powerfully influences behavior. Freud brought it into the mainstream of Western thought through exhaustively detailed revelations of its effects on behavior. But few, including Freud, have spoken of liminal consciousness, which is therefore rarely recognized in modern scholarship as a separate type of awareness. Nonetheless, liminal awareness was the principal focus of mentality in the preconquest cultures contacted, whereas a supraliminal type that focuses logic on symbolic entities is the dominant form in postconquest societies { } Preconquest groups are simultaneously individualistic and collective–traits immiscible and incompatible in modern thought and languages. This fusion of individuality and solidarity is another of the profound cognitive disparities that separate the preconquest and postconquest eras. It in part explains why even fundamental preconquest cultural traits are sometimes difficult to perceive, much less to appreciate, by postconquest peoples.{ } Only when awareness shifted from liminal to supraliminal did the notion of ‘correctness’ become a matter of concern – e.g., behaving ‘properly’, having ‘right’ answers, wearing ‘appropriate’ clothes, etc. ‘Improper’ aspirations, inclinations, and desires were then masked as people tried to measure up to the ‘proper’ rule and standard.”

E. Richard Sorenson (Tribal Epistemologies: Essays in the Philosophy of Anthropology).

Instrumental thinking, and what Horkheimer called the eclipse of reason. And the basic repression that drove Puritan piety and their fixation on punishment and purgations. American culture naturally gravitated to eugenics and a classificatory sensibility.

Laurent Millet

“I cannot grasp all that I am”.

Augustine

“Brain activity is distributed among numerous specialised sub-systems (i.e. groups of cells that work together to perform a particular function); yet none of these sub-systems is conscious. Moreover, there is no special place in the brain where the products of these sub-systems (such as the objects of perception and emotions) are knitted together. No place where a conscious experience is constructed. This has led many neuroscientists to conclude that the sense of self that we all share is nothing more than an ‘illusion; that identity is to the brain what the shape of a wave is to sea water. Contemporary neuroscience seems to suggest that our most prized possession – the ego -barely exists. We (as we know ourselves) have only a feeble claim on existence.”

Frank Tallis (Hidden Minds)

There are many people today who find it easier to just believe there is no such thing as the unconscious. That such a belief has even been abandoned by neuroscientists is worth noting. And of course there are a host of philosophical problems linked to the *location* of thought or mind, etc.

Hans Asperger checking Polish children for Reich suitability.1942. (courtesy of ©SZ Photo / Scherl / The Image Works )

Robert Zhao Renhui, photography. (Migrant vulture, India)

In another respect, in many personal memoirs of awakening, whether quasi mystical or psychoanalytic, there is the creation of a space — call it a dream space — and invariably this is an empty space. Jung wrote of peering into a cosmic abyss etc. These spaces are all theatres of the mind. The imagination that looks to describe the unconscious, or describes dreams, is somehow writing a play. That empty space Peter Brook wrote of, and Blau, is the place from which our sense of self is constructed. And this is something, that likely, is innate. But that space can be filled in various ways, again according to class and region and language even. Or the space is a space of a particular natural environment. Classical Greek imagery is built upon the landscape of southern Greece, with grottos and wide blue skies and azure seas. And white stone and sun.

There is more to it than that, however. The space that is conjured from the unconscious has sedimented materials somehow at its disposal.

“… Nevertheless, Jung suggested that archetypes are best construed as psychic ‘deposits’ – the residua of humanity’s repeated encounters with similar experiences, situations, and narratives. The motion of the sun serves as a particularly good example of a recurring, ubiquitous phenomenon that has clear narrative implications. Every day the sun rises, travels across the sky, and then sinks below the horizon; however, after a period of darkness, it is apparently reborn, bringing light back to the world. Jung suggested that the narrative structure of the solar cycle has acted as a template, facilitating the emergence of countless sun-hero myths. The theme of descent into the underworld, followed by a heroic return, can be found in folklore the world over. ”

Frank Tallis (Hidden Minds).

This is fairly obvious, and yet it is disquietingly imprecise. Other archetypes have a different valence; the wise old man is an archetype that functions as a sort of mental librarian for repressed materials. At least if we believe Jung. The point for this posting is that while much of the drift away from the Id in psychiatry possessed certain progressive aspects (in Laing for one) the overall effect of a focus on the processes of the ego meant that given the class make up of the West, and U.S., a tendency toward conformism, sex negative Puritanism, and a huge uptick in marketing and commodification. Nobody cared anymore about those dark grottos of the mind. It was seen as being ‘negative’ to dwell on such stuff.

Jeff Brouws, photography.

Photographs of empty streets at night are always evocative. There is always something uncanny lurking at the edges. Especially if these photos are of cities, or at least places in which humans have obviously left their imprint (Serge Najjar, to my mind, ruins his photos by putting someone in them, for its a way of suggesting irony and cleverness at the expense of the uncanny and transcendental. Compare to the work of one of my favorites, Awoiska Van der Molen). But all art, if its any good at all, elicits a shock of the uncanny — or, maybe its better to say that the artwork, if we are talking painting and sculpture, disrupts the sense of security found in expectations being met, in the familiar. Sculptures, hyperrealist or classic or abstract are largely refiguring space around the viewer. These are obvious remarks, and yet today increasingly there is an inability to experience awe or wonder, because again a culture of domination, a Puritan culture, cannot allow the unruly qualities of dreams to be taken seriously. Fun is prescribed. Fun is controlled. The addictions of screen use today are more or less encouraged because of Capital. But also because they form a closed system in which one does not awaken, but is kept asleep.

Ysavel Lemay, mixed media.

“Schizophrenic individuals often describe themselves as feeling dead yet hyper-alert, a sort of corpse with insomnia; thus one such patient spoke of having been “translated” into what he called a “death-mood/”.

Louis Sass (Madness and Modernism : Insanity in the Light of Modern art, Literature, and Thought)

“Curiously, many patients who have long given the impression of being severely incapacitated may, under the right circumstances, show themselves to be quite capable of intact speech and intellectual functions, of appropriate emotional reactions, and even of making practical decisions and cooperating with others. When a major flood hit Topeka, Kansas, in 1951, one psychologist from the Menninger clinic was “astonished … to see chronic schizophrenic patients—some of whom had been hospitalized for over twenty years—not only loading and placing sandbags with the rest of us, but effectively supervising us in the loading and placement of the bags.” The patients kept this up for several days; then, once the emergency had passed, they resumed their back-ward existence”

Louis Sass (ibid)

This is quite important, the incapacity is clearly, often, an idea with pretty fluid parameters. And when contemplating both schizophrenia, and autism, the idea of creativity is put in stark relief. There is a fashionable cynicism about art and artists today. There is probably no easier figure to ridicule or be snarky about then the artist. The cult of the genius is blamed, in a sense, and its not totally without merit, because indeed that particular kitsch meme saw itself treated in pop culture for fifty years. The suffering lonely misunderstood genius. But in fact the idea of creativity, especially the creative child, is one who is likely going to subjected to very harsh procedures that are meant to correct his errant fixations with private worlds and day dreams. That children draw remarkable things is not a cliche, its simply true. And the drawings of children are conspicuous in their freedom and openness. Much as the creative output of mental patients has come to be recognized for its unique anti commodity qualities. This is the so called *outsider art* that is now, actually, being commodified. Christies and Sotheby’s are finding a growing market for the work of men and women, most of them schizophrenics (and most dead) that seem to express a quality of disobedience. This is how expressions of dissent are incorporated by the system.

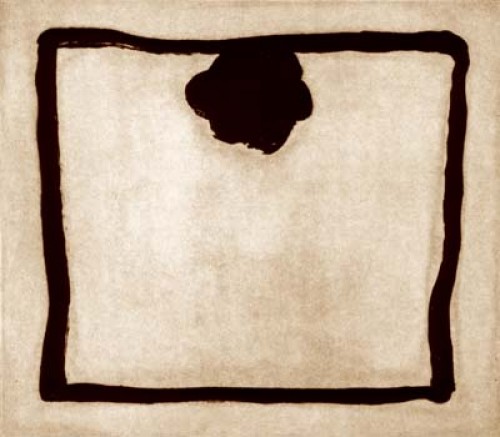

Joan Hernández Pijuan

Hemingway wrote this after his second trip to the Mayo Clinic where he received a series of ECTs. He killed himself with a shotgun two days after the treatment and left this note.

“What these shock doctors don’t know is about writers…and what they do to them.… What is the sense of ruining my head and erasing my memory, which is my capital, and putting me

out of business? It was a brilliant cure but we lost the patient.”

What I am trying to get here, through a lot of digressions, is that contemporary society, Capitalist society, especially in the United States, continues to ruthlessly neutralize not just politically dissent, for that is obvious, but it continues to simultaneously construct a society that kills off creativity, sensitivity, and that punishes those personalities that do not fit into the American exceptionalist intellectual diorama. I loved the Museum of Natural History in Los Angeles, when I was young boy. I love the dioramas. I’d never wanted to leave and had to be dragged away. And in a way that is what the current system is doing. It creates a diorama to replace society, to replace community. It does it through screens, and electronic and digital technology. It makes people, users, products. Attention is monetized. And to sustain these fictions the new version of Nazi doctors sit surveilling the endless data streams that are housed in some impossibly huge and silent building in Utah. They tinker and fine tune these cyber dioramas, but its also that reality, daily life, is taking place in frozen dioramas. The streets of America are very like the natural history museum, giving one a bewildering sense of inside/out vertigo.

The fictions this society creates denies its own virulent racism, and most importantly it denies the class hierarchies that help sustain the privilege of a very few. One walks through American cities, or towns, as if in the land of the dead. Nobody makes eye contact, nobody smiles (unless they are selling you something) and the bodies of this denizens of what Henry Miller called ‘the air conditioned nightmare’ lack all spontaneity. Suddenly the journeys of Homer or Dante make considerably more sense.

Richard Barnes, photography.

Art and culture is constantly denigrated, with target audiences on both the right and left. The right is given permission, no, encouraged to hate modern art, to hate artists, and are constantly reminded how little use art has. The left is sold exaggerated stories about the CIA actually being the force behind much modernism (especially the now tedious story about Abstract Expressionism). The left is encouraged to embrace reductive and simplistic positions about art and culture (and about psychoanalysis for that matter) as if somehow such subject positions serve as an extension of materialism — and one thing I would wish more than anything is that the left had better taste in cultural matters.

Abstract art is easy to make fun of, mostly because there is so much of it that is bad. More all the time. The economic colonization of museum and gallery directors, and the insane (and planned) elite financialization of art as it is found at Biennales, and auction houses, only fuels resentment and disdain. And it cements class exclusion. Art education is mostly gone the way of the buggy whip and what is left is an education in the business of art, in how to build a brand. And all of this marketing, pro and con, only works to the degree that it does, because of the constant drum beat of conformity and the constant exclusions of each new generation of disobedient young artists and thinkers. One no longer needs sub orbital lobotomies because one has facebook and google.

Postcard fpr Utah State Mental Hospital.

Again, to donate to this blog use the paypal button at the top of the page. For those that have and will, it is hugely appreciated.

And for details on my workshop scheduled for late September in LA, just write me via email, my address is under *contact* … also at the top of the page.

I have a contract this semester as a teaching assistant for a second year English Literature course at the university on Shakespeare’s Tragedies. The course is taught conservatively–the students read a play and go to (or usually skip) two lectures a week, and a discussion-based tutorial on the play in question. The play is approached in terms of providing historical context, “theme”, “plot”, and basic meaning, as many of these 18-20 age-ish students are lacking considerable ability to read and comprehend any of Shakespeare’s writing.

Despite being contracted by the English department, I am actually a trained actor and approaching English literature like a typical English scholar is less natural to me than approaching research the way an actor might. I devised a workshop for the students to do a close reading of Act 1. sc. 3 of Hamlet, paying particular attention to the famous “to be or not” speech. I posed a series of questions for the students to answer that an actor might ask themselves when preparing to perform “to be or not” in the role of Hamlet–questions that a passive English student reader might not think were at all important to writing a paper on the “themes” or “meaning” of Hamlet–questions like: who is on stage during the speech? What happened right before Hamlet’s entrance? What does Hamlet know that the other actors on stage don’t know and vice versa? Does Hamlet know Ophelia is there? What time of day is it? Why did Hamlet enter? etc, etc. These questions can be answered (or approximated) with evidence from the text itself–hence it making a good “close-reading” practice exercise.

After getting the students to collect a lot of data from the text, throughout workshops that week, I took the close-reading notes and used it to do what I called “embody the thesis.” I told the students that as English students, they read a play, write an essay with an argument and hand it in for grading. But the actor’s thesis is not written down, it is embodied.

Now there are a ton of different directions I could go with what I learned doing this exercise with the students, but for now I’ll focus on madness. The question came up in relation to this famous “to be or not” speech: is Hamlet mad? Is Hamlet feigning madness during the speech? Is he actually going mad? …I extrapolated more, urging the students to ask harder questions: Can you feign madness so well that you become mad? What, in fact, is madness? Is it more mad to contemplate suicide because your father has died and given you a difficult task, you’ve been abandoned by your uncle and mother to a hideous wedlock, and all your friends have become spies? OR is it madness to murder your brother and marry his wife for the kingship? Does madness have a location? Is it something that one possesses, or is it something that arises from a complex set of environmental, social and historical circumstances, which our capitalist-colonialist narratives like to ignore in favor of metaphors of “possession”, individuality and responsibility? If we agree that Hamlet is, at this point at least suffering severely from mental affliction, could we not say his “mental illness” or madness is not, in fact, caused by his impressive level of awareness and sanity? Does madness arise due to “outrageous fortune” (trauma), or to our conscious awareness of such fortunes, or to our lack of consciousness of them?

Another question is of an actor-ly nature that many English students were not equipped to understand. There is this vague idea that the actor, playing Ophelia say, will “play madness,” and “be” mad. But to do an honest performance, one cannot simply “play” an emotion or mood; one must find the meaning or reason, or image that compels the actor/character to do or say what she does. I would argue that any sort of madness has its own logic–even if all the world’s best intellects cannot tease it out. We might be able to know a lot more about “mental illness” and madness by performing it, or (dare I say) empathizing with it–again, a kind of approach to learning that highlights creativity and listening rather than reductionism and telling.

Sadly, I don’t think the students were able to see how the play, Hamlet, might challenge some of our taken-for-granted notions of what “madness” is. These questions drew a lot of silences. But all is not lost. I might add that sometimes, within these silences, there is a kind of ominous weight that falls and enters into the space. I like to believe that this ominous presence–even if only momentary–begins to reawaken our abilities to feel into that awe, respect and wonder of the uncanny and the unknowable that the academic (and all capitalist-colonial institutions) do their best to obliterate. The DSM culture loves to pretend to know everything and create neat and tidy categories and locate madness as “illness” within individuals who are responsible for curing themselves and/or who others are responsible for “curing” or saving–in the style of the “white savior” co-dependent culture the mainstream west lives by…. And so we lose the mystery, and the history of trauma as creating symptoms within the psyche and body and we lose a kind of patience to accept and explore the way-of-being of mental distress: English students are being asked to come up with an argument about how madness works in a play like Hamlet and it is completely out of their realm of thinking to have a teacher perform Hamlet and have to watch Hamlet grapple with his own consciousness. That the state of affairs of Denmark and the history of fratricide is being played out in the emotional/psychic state-of-being of a young man reveals the stakes of how inevitably we are all both individuals and, inextricably, deeply connected despite what the American Dream would have us believe otherwise. This is also, one of the reasons why I believe theatre is the most subversive art form to the west: its very form DOES what capital power cannot tolerate: it remembers and makes conscious our deep connection with one another, and when done well, it can do this by bypassing the intellect and working through affect, so it cannot be so easily controlled by a reason-based (sic) system.

oh man, i could write a thousand different responses to this posting…..these topics are totally part of my research and observations for the past 7 years. I could provide a lot of stories and examples to support many of your observations here….but thinking of Hamlet and the role of art…

Great art, I think can offer and open up possibilities for re-thinking and questioning the meaning of a lot of terms and cultural movements we take for granted, like “depression” or “madness.” Trouble is, in a lot of underfunded Humanities departments, the focus (as mentioned above) is more on marketing and ‘making it’ in a media, capitalist driven society and the hard and interesting questions that make life exciting and shift our understanding of what power is and where it lies, are simply not being asked. I happen to believe that curiosity itself is a great protection against depression. It is probably one of the key reasons I was able to get myself out of over a decade of dependency on psychiatric drugs (as mentioned above, they don’t work, it was more the narrative surrounding them that I was dependent on), and learned to think about (and exist as) my self and life in a very different way. After over a decade of being told: “you have a condition, you’ll always be at risk of suicide and episodes; you can never come off the medications, etc.” –one day, into a 4-year “depression”, and feeling numb and awful and angry that I was being told these things, and yet still hated my life and wanted to die–one day, the thought came into my head: But what if they’re all wrong…? And that thought i guess kind of hit me on an existential level. I quit the drugs to find out what the depression felt like un-muddied by the drugs and I quit the medical system and started studying human behavioural biology to see whether they were right about these illnesses and drugs and to find out why they didn’t work for me. I started studying medical anthropology. Curiosity to find out what was going on with me and why nothing worked led me, not only to some pretty hard truths to comprehend for someone actively deluding themselves all this time, but that very curiosity itself, helped to eliminate many depressive symptoms, and the more symptoms gone, the more energy I had to get curious about the other ones and find ways of changing them too.

Curiosity is dangerous. It’s like memory…..you remember the trauma and speak truth to it and it can’t hold you in the same way it used to.

I’m autistic or “aspie” as they used to call it (funny that Hans Asperger’s Nazi career and treatment of “gemut-poor” children was known all along but the “condition” got named after him anyway–for a long time. Anyway all this rings very true–I was undiagnosed for most of my long life and the constant need (beat into me very early) to not upset people was far worse than any condition I suffered. The thing is, when autistic people feel bad (to generalize, sorry) we feel BAD and you can’t talk or threaten us out of it, or cheer us up, or joke us out of it or any of that crap. It has to pass on its own. And that absolutely terrifies people, I’ve discovered. They hate it. It’s like you’re somehow a traitor to their whole hysteria driven cheer project.

thanks, Glena. Very interesting last observation.

I’ve been reading this blog for years and it is my favorite. I find so little on the internet that is truly thought provoking and broadening of perspective. This one in particular I feel is essential reading and it also struck me personally.

Just a day before reading this post, I was out doing something very abnormal. It was a beautiful day in the small Southern city I live in and I decided to walk between appointments. I have been a dedicated walker for decades and my amazing feats shock and amaze others. Nobody walks to get from point A to point B (except in nyc and outside the states). I have literally walked 20, 30 miles to get somewhere in other cities, not because I had no other option but because I enjoy it, if the weather is nice, if I have the time, it is exercise for the body and mind. So, on one of the most perfect spring days when I thought walking would be fun, I ventured from my home to my business, a journey of 4 miles with decent sidewalks all the way in between. Nobody else was walking. The only people I encountered on my walk were homeless people, one driver who rolled his window down to ask if I needed a ride (why on earth would I be walking on the most gorgeous day of spring?) and one driver who honked and yelled something at me (not sure what but didn’t seem friendly). I can tell many stories over the years of rudeness directed at me merely because I was walking on a city sidewalk or people offering help because they assumed I must be in distress instead of enjoying the activity of walking. That’s why I feel at home whenever I visit nyc or a sane country.

Anyway, from mild matters … this discussion of “mental illness” and “psychiatry” is so very crucial and of course because this is America nobody knows how to approach it other than to defer to doctors and pharma and popular culture and certainly not their own critical thinking or cultural approaches. This is a passion of mine and I am working on a couple of creative works exploring this theme.

One of the most persistent, sad, and hilarious memories from my college years relates. I went to a “prestigious” old college that is well known for producing grads who make lots of money. When I was in high school I thought that’s what I wanted. Fortunately when I got there I was lucky to connect with with most free thinking and creative professors there who turned out to be good mentors and I got to travel a lot. But by my junior year I was figuring out how the world really works and questioning why I was at this school and why I would want to pursue any of the career paths that were typical and lucrative. I was also starting to turn in assignments and papers that were nonconforming and some of my professors loved me and some hated me. But mainly I started questioning so many things. I had grown up in a depressing rural environment with a father who was just “not there” (he was a Vietnam vet who lived with a massive amount of rage that would spill out and he had been doused with so much Agent Orange and the health effects just kept mushrooming until he died of a massive, massive stroke at a “youngish age”). But I also grew up in a community that included Robert Bly and his ex wife Carol Bly and I was exposed to his poems and her stories and their thinking from a very impressionable age.

Alas, sitting in my dorm room on this beautiful campus I was wondering why I was there and what my future might be. And I realized that I didn’t want to go through the process and tamper my insights and creativity so I could be just another “successful” grad. I could have done that but I wanted an authentic life. And there was very little support for that. I felt just a little alienated. There were kindred spirits in unexpected places and especially on my trips abroad but when I returned to campus I felt mostly stifled. Even the most encouraging people would eventually say, “well you know that’s all fine but you gotta…”

I wrote a letter (on paper!) to a dean who I had met a couple times and thought of as a kindred spirit but I didn’t know well. I had read between the lines of a profile done on him for a higher ed publication and thought he had gone through similar period in his college days. (of course he had eventually made peace with the establishment and that’s why he’s now a college prez and serving on corporate boards). But I was naïve at that time.

Apparently my letter set off alarm bells in the admin bldg. and they thought it was a suicide notice. I had just thought I could get deep with him and had hoped he would invite me for coffee and solid human conversation. To get to the “hilarious” part, a day after I sent the (paper) letter, I had had a really great day … was feeling creative, had good conversations, and was busy with projects (even though I was half hearted about the overall context of college life) … had gone out to see a movie with a romantic interest and returned to my dorm room. Was listening to classical music with said interest, and then there’s this loud banging on my door. I have not got a clue why … I jump out of bed, the room is dark, and I slowly open the door a crack. There are 2 campus security officers coming to check on me based on the letter I sent to the dean……. I was out all day and had not checked my voicemails that I later found out included a VM from campus security making sure I was ok.

TBC

very interesting . Oh, and as for walking, I do it too. Its tough in winter in norway but all summer I walk about 8 miles a day. And Id do more if I just had the time. Walking brings sanity.

I totally hear you about the disillusionment with the academic institution, Jay. I have a lot of trouble with the academic institution, but then again, I have avoided some of the incredible stress and disillusionment I see many of my grad colleagues going through because ever since i finished my undergrad and decided to go back to do my masters and then phd, I did it for very unconventional and personal reasons, so the stakes are different for me than a lot of my peers.

And I have a few intriguing stories myself about run ins with security revolving around mental health accusations. In the end, these encounters always played uncannily well into my hand and turned the tables on them and their own assumptions. I kid you not, I was in a meeting getting a wrist slap by a couple higher ups in the establishment for a massive cross-campus “artwork” I had been doing and in under 15 minutes the question of whether I had been in “crisis” shifted to asking me whether I would TALK TO THE DIRECTOR OF STUDENT WELLNESS and offer insight for HELPING HIM think through how to use reactions to artwork to deal with students in mental health crisis. I mean….what the fuck!?! I’m a scrawny, sidewalk chalk drawing phd student who you just hinted might be going through a crisis and now you’re asking me for advice for the director of student wellness?? Like, who is getting paid the big bucks here? He’s the DIRECTOR of student wellness for fucks sake! Like…can’t he do his fucking job?!? (Well, no, of course not, and we all know the way psych issues are handled really suck in most Western mental health institutions, but that is what was so fascinating about what happened here and how the work I was doing revealed the lack of integrity in the system and really turned the tables on who or what was “mentally ill” here…). For the record, the “artwork” I was doing was NOT “about” mental health. It didn’t have an “agenda” or anything instrumental to it and I think that is what really creeped them out….

But yeah, it is a dangerous place for illusions to establish themselves–especially around class and what kind of knowledge counts as knowledge. Sadly, I see a lot of professors who lose their curiosity and integrity and creativity and their unique self because they become intoxicated by the professor persona: the office, the publications, the tenure, the conferences, knowing the who’s who, etc. The Persona becomes like a drug or a kind of armor and over time, it protects you from the truth and limits possibilities for seeing the world in new ways and also limits our ability to change and grow. Sadly, lot of truths about class go unacknowledged. It can’t go on forever like this though….the way academia is run in capitalist west is unsustainable. I’m lucky because I also work as a part time custodian at the university (so I clean the toilets the dean and profs shit in)…..and I learn something different about what really matters in the world when I shift into these different roles from TA to custodian, to grad student, to anonymous “artist”….I dunno, but I really just don’t think I could get too motivated to read theory if I didn’t also do labour and do work in public spaces with and for people.

anyway, thanks for sharing, Jay. Liked your story.

on walking….incidentally, I just got back from a 3 hour walk in the woods. I live in southern Ontario, Canada, so the earth has just thawed. I took off my shoes for about an hour and walked with the mud squelching between my toes. I climbed the escarpment where there’s a beautiful view of the city and one of the great lakes. Then I washed the mud off my feet and ankles in the frigid water at the top of a waterfall. It was beautiful. I only saw a few other people on the trail. And lots of turkey vultures.

yeah, walking is good medicine. So is mud and earth next to the skin.

Cheers. I think walking is drastically more important than 99% realize …. All my best thoughts come from it. I’m also a Finnish citizen and have spent many years in Helsinki and have walked every block of that city and never had a negative experience. I remember telling colleagues at places I worked in Seattle (where I’ve lived most of my adult life) that it made more sense to walk 12 blocks than take a car and then when I did it they saw me en route and offered me a ride…

I have a good friend in Florida who writes good books on people who walk and also wrote a series in the Tampa Bay Times about his experiment getting around on foot for a week in his home city.

https://www.tampabay.com/features/books/Review-Ben-Montgomery-s-Man-Who-Walked-Backward-lets-readers-step-into-history_171495308

Great stuff, as ever. Reminded me of a study from a few years back of the auditory hallucinations experienced by those diagnosed with schizophrenia:

https://news.stanford.edu/2014/07/16/voices-culture-luhrmann-071614/

“Tanya Luhrmann

Tanya Luhrmann, professor of anthropology, studies how culture affects the experiences of people who experience auditory hallucinations, specifically in India, Ghana and the United States. (Image credit: Steve Fyffe)

People suffering from schizophrenia may hear “voices” – auditory hallucinations – differently depending on their cultural context, according to new Stanford research.

In the United States, the voices are harsher, and in Africa and India, more benign, said Tanya Luhrmann, a Stanford professor of anthropology and first author of the article in the British Journal of Psychiatry.

The experience of hearing voices is complex and varies from person to person, according to Luhrmann. The new research suggests that the voice-hearing experiences are influenced by one’s particular social and cultural environment – and this may have consequences for treatment.

In an interview, Luhrmann said that American clinicians “sometimes treat the voices heard by people with psychosis as if they are the uninteresting neurological byproducts of disease which should be ignored. Our work found that people with serious psychotic disorder in different cultures have different voice-hearing experiences. That suggests that the way people pay attention to their voices alters what they hear their voices say. That may have clinical implications.”

Positive and negative voices

Luhrmann said the role of culture in understanding psychiatric illnesses in depth has been overlooked.

“The work by anthropologists who work on psychiatric illness teaches us that these illnesses shift in small but important ways in different social worlds. Psychiatric scientists tend not to look at cultural variation. Someone should, because it’s important, and it can teach us something about psychiatric illness,” said Luhrmann, an anthropologist trained in psychology. She is the Watkins University Professor at Stanford.

For the research, Luhrmann and her colleagues interviewed 60 adults diagnosed with schizophrenia – 20 each in San Mateo, California; Accra, Ghana; and Chennai, India. Overall, there were 31 women and 29 men with an average age of 34. They were asked how many voices they heard, how often, what they thought caused the auditory hallucinations, and what their voices were like.

“We then asked the participants whether they knew who was speaking, whether they had conversations with the voices, and what the voices said. We asked people what they found most distressing about the voices, whether they had any positive experiences of voices and whether the voice spoke about sex or God,” she said.

The findings revealed that hearing voices was broadly similar across all three cultures, according to Luhrmann. Many of those interviewed reported both good and bad voices, and conversations with those voices, as well as whispering and hissing that they could not quite place physically. Some spoke of hearing from God while others said they felt like their voices were an “assault” upon them.

‘Voices as bombardment’

The striking difference was that while many of the African and Indian subjects registered predominantly positive experiences with their voices, not one American did. Rather, the U.S. subjects were more likely to report experiences as violent and hateful – and evidence of a sick condition.

The Americans experienced voices as bombardment and as symptoms of a brain disease caused by genes or trauma.

One participant described the voices as “like torturing people, to take their eye out with a fork, or cut someone’s head and drink their blood, really nasty stuff.” Other Americans (five of them) even spoke of their voices as a call to battle or war – “‘the warfare of everyone just yelling.’”

Moreover, the Americans mostly did not report that they knew who spoke to them and they seemed to have less personal relationships with their voices, according to Luhrmann.

Among the Indians in Chennai, more than half (11) heard voices of kin or family members commanding them to do tasks. “They talk as if elder people advising younger people,” one subject said. That contrasts to the Americans, only two of whom heard family members. Also, the Indians heard fewer threatening voices than the Americans – several heard the voices as playful, as manifesting spirits or magic, and even as entertaining. Finally, not as many of them described the voices in terms of a medical or psychiatric problem, as all of the Americans did.

In Accra, Ghana, where the culture accepts that disembodied spirits can talk, few subjects described voices in brain disease terms. When people talked about their voices, 10 of them called the experience predominantly positive; 16 of them reported hearing God audibly. “‘Mostly, the voices are good,’” one participant remarked.

Individual self vs. the collective

Why the difference? Luhrmann offered an explanation: Europeans and Americans tend to see themselves as individuals motivated by a sense of self identity, whereas outside the West, people imagine the mind and self interwoven with others and defined through relationships.

“Actual people do not always follow social norms,” the scholars noted. “Nonetheless, the more independent emphasis of what we typically call the ‘West’ and the more interdependent emphasis of other societies has been demonstrated ethnographically and experimentally in many places.”

As a result, hearing voices in a specific context may differ significantly for the person involved, they wrote. In America, the voices were an intrusion and a threat to one’s private world – the voices could not be controlled.

However, in India and Africa, the subjects were not as troubled by the voices – they seemed on one level to make sense in a more relational world. Still, differences existed between the participants in India and Africa; the former’s voice-hearing experience emphasized playfulness and sex, whereas the latter more often involved the voice of God.

The religiosity or urban nature of the culture did not seem to be a factor in how the voices were viewed, Luhrmann said.

“Instead, the difference seems to be that the Chennai (India) and Accra (Ghana) participants were more comfortable interpreting their voices as relationships and not as the sign of a violated mind,” the researchers wrote. “

Thanks for posting that in full.. and not for nothing but this just brought to mind the picture of Chinese mothers holding their babies out in the street, we are so plastico it’s not funny

… a post-human tabula rasa in which we get reconfigured inside and out…

I find the speed with which these digital enclosures have been erected and have acquired material force to be shocking (a link via Frank Pasquale might be of interest here https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/nulr/vol105/iss3/4/ )