Mira Schor

“In Europe as well as the United States, the erosion of industrial employment through wage arbitrage, outsourcing, and automation has gone hand in hand with the precaritization of service work, the digital industrialization of white-collar jobs, and the stagnation or decline of unionized public employment.”

Mike Davis

“The world of dreams is a living forest in which fantasy dwells in a state of riddle…”

Salomon Resnik

“The invention of perspectival representation made the eye the center of the perceptual world as well as of the concept of the self.”

Juhani Pallasmaa

“The truth is that not only are we not Christians but we âre not so much as pagans, to whom the Christian doctrine could be preached without embarrassment; but by an illusion,

a monstrous illusion.”

Kierkegaard

I drove from central Norway down to Copenhagen this last week. I was taking some off to work on my new play. I drove through Sweden rather than Norway and I wandered along smaller roads and was taking my time. Two years ago I drove across Europe, ending in Prague. I meandered, touching down in Germany, in France, Belgium, and eventually the Czech Republic. It has been a decade since I had that kind of drive in the U.S. But I remember similar feelings then, too. One cannot find a single small city, or large town, anywhere in Europe or the U.S. that feels happy. No place where enthusiasm and optimism are readily apparent. Instead one is met with an endless soul destroying panorama of boarded up storefronts, discount shopping stores, for groceries and clothes, for most of anything. Even the big malls, such as Field’s in Copenhagen, feel depressed. Nothing feels particularly well maintained. As it happens Copenhagen might be the least miserable of cities I have visited. But even there I found a sense of psychic discontent. It is hard to define or even describe. In Sweden, as I stopped outside Jonkoping, I looked around as I stood on the main street of this city of 90 some thousand — and what one sees are homes built either a hundred or a hundred and fifty years ago, or others built probably in the 1970s. Seems less built in between those eras. There is not much new construction in such cities. Jonkoping is an old agricultural town, though today it is better known for being a computer gaming center.

Oakwood Theatre (date unknown, Toronto) Photo courtesy of Mandel Sprach

Immigrant areas always feel more lively in the cities of Europe. And the food is usually better. There is money in Scandinavia, and lots of people drive newer Volvos or Audis and there are posh areas to be sure, in nearly any city over a couple hundred thousand. But you don’t see faces of joy and life. The affluent class seem as miserable as anyone these days. Less fearful, perhaps, but just as depressed. In the U.S.,last time I was there, the sense of malaise driving across those flyover states is just palpable. And part of how this malaise is expressed in the ugliness of everything. Literally, everything touched by humans living under Capitalism, registers as ugly.

But, what I find interesting is the way the populace of the U.S., and of Europe for the most part, has had inculcated certain experiential processes. The automatic ways that people function in a daily life that seems intolerable to most of them. Literally intolerable.

Ana Maria Micu

I have this sense of habitual emotional unease — that immiseration has been repackaged as something psychically generated, and the coping mechanisms to this selling of personal failure as the reason for unhappiness is now found in ever more rote repetitive and obsessive patterns of activity. The people in western societies today are told their psychological and emotional problems are the result of personal failures. Even, perhaps, moral failures. The behaviors are not large or obvious. They are small, and often subtle, and often almost kept out of sight. People seem to lead increasingly split existences. One is living on one’s smart phone, and one is living in some way with family (more on that below) and one is also living in some personal private movie. Or private reality TV show.

One can see how these overlap, of course. And there is something else, too. The filmic quality of daily life can hardly be accidental. People are now unconsciously (or maybe consciously, I don’t know) reproducing their own lives as if they were movie producers … but producers for some low budget studio that grinds out endless melodrama and cheap romance. People star in their own films, but they are cynical filmmakers.

Farida El Gazzar

There is a quality of nostalgia that accompanies any examination of reification. And this is relevant now because as Michael Wood suggested, the public love for the 50s is about the fantasy that Hollywood manufactured at that time, not for anything resembling the actual 50s. So today, the private theatres of the mind are creating their own stories as if told in flashback, and set in various fantasy decades. It is almost as if people live their compulsive repetitive lives in flashback sequences. And it was Wood who also said flashbacks in the films of the forties and fifties was not a narrative device but a compulsion. Small cities in the U.S. and Europe, and even relatively large ones, seem to now exist in a kind of psychological version of radioactive half life. We are at that point in our psychological decay. And this in turn reminds me of Noel Burch’s book on the early cinema (a significant book by the by). Burch posits that there has been a normalizing of the Hollywood system of representation in film. That this system was in no way inherent in the technology itself.

“I see the 1895-1929 period as one of the constitution of an Institutional Mode of Representation (hereinafter IMR) which, for fifty years, has been explicitly taught in film schools as the Language of Cinema, and which, whoever we are, we all internalise at an early age as a reading competence thanks to an exposure to films (in cinemas or on television) which is universal among the young in industrialised societies.”

Noel Burch

The specifics of cinematic grammar, all based on montage, are not so much the point here (though I very much recommend Burch’s book), but rather the ways in which this mode of representation has become dominant in a wider political sense.

Rebecca Salter

“Indeed, if the researches that culminated in the invention of photography corresponded in immediate awareness to an ideological drive, it is just as clear that this new technology objectively answered a need of the descriptive sciences of the period (botany, zoology, palzeontology, astronomy, physiology). At the same time, it should not be forgotten that the economic expansion and accession to political power of the bourgeoisie were closely linked to advances in the sciences and in technology, and that hence by evoking the strictly scientific effects of some instrument or mode of representation we are by no means leaving the historical terrain of the relations of production.”

Noel Burch

Bourgeois illusionism, then, drove cinematic techniques — both as a suppression of death (the Frankenstein syndrome) but also a validation of their class and its values. Burch has two very good chapters on the national differences (class differences) that shaped the cinema that evolved from the 1880s, say, to 1914. It is interesting because there is a certain bourgeois truism that has film as the entertainment of the poor, ‘the poor man’s theatre’, and the nature of the bourgeoisie and the proletariat in Italy, Sweden and Denmark, differed from that of France and the U.K., and a bit later that of the U.S. These were the foundational countries for early cinema. It was in the U.K, though, with its penchant for Puritanism coupled to strict class coding and class markers, that most insistently reproduced what Burch is calleing the IMR.

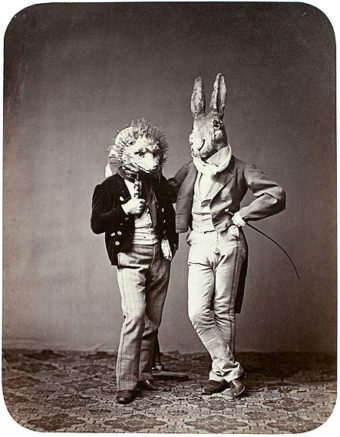

Joseph Albert, photography (collodian) 1862.

“The development of French cinema before the First World War-—-or rather its relative non-development——cannot, of course, be reduced to the history of the class struggle in France or the relatively slow industrial growth of that country: relatively autonomous cultural factors like middle-class and aristocratic elitism or the exceptional strength of popular counter-ideologies, factors which are nonetheless class-based, were also determinant. As for the more contradictory situation of British cinema, it seems to me a faithful reflection of the development of the ideological struggle in Britain at the time, when, thanks to homogenisation strategies such as Rational Recreation, the viewpoint of the ruling classes achieved hegemony, but working-class culture was acquiring institutions that guaranteed its persistence, most notably with the creation of the Labour Party. In the USA, whose vanguard role in the development of the IMR is outstanding, class relations were equally important, but also more ‘violent’, in the sense that the path the cinema took there implied the rejection of a whole social stratum despite the fact that most of its audience for more than five years came from that stratum.”

Noel Burch

Again, what matters here for the purposes of this posting is the effect these historical trends had for how this *IMR* insinuated itself into larger aesthetic fields, as it were. And how that wormed into the psychologies of western capital. The *IMR* really is just the entrenching of certain techniques in editing, but also in camera placement that emphasize linear narratives.

“Now that contemporary stylistics allows almost any temporal relationship-—flashback, ellipsis or simultaneity——-to be expressed by a mere shot change, to the exclusion of dissolves and other optical effects, the emergence of the alternating syntagm has to be seen as the foundation-stone of modern syntax.”

Noel Burch

“Photography destined to duplicate Hegelian closure, to produce mechanically the ideology of the perspective code, of its normality and its censorships.”

Pleynet & Thibaudeau

Anton Raederscheidt

And there is no question, in one sense, that photography took easily to the ideology of progress and forward looking trust in work. But film grew strangely and was linked with entertainment or leisure activity, which itself was evolving strangely through its own reactions to class and trade. From seaside amusements to county fairs to music hall alleyways, the entire story of early film is tinged with various national treatments of class. When film did get to a more organized presentation it is notable that uniformed ushers were employed to keep the riff raff in line and not bother the customers in the good seats. The business of entertainment took on the appearance of school or factory (or prison). And something happened at this point. When still an amusement at an arcade films rarely lasted more than ten minutes, if even that. As the technology advanced to allow longer shoots the relationship of cinema to theatre became more pronounced. Now, what Burch calls the Lumiere model in early cinema was that which looked to linear storytelling and clear cues about perspective (even if not met) and with this a kind of implied morality of Renaissance perspective. Worth noting that those films all used painted backdrops…often if not usually black. I suspect this is even more significant than Burch realizes. For this is related to shadows and darkness.

George Spencer Watson (1922)

One of the great books of aesthetics in the 20th century is In Praise of Shadows by Junichiro Tanizaki. Perhaps because I read it during the time I lived in Thailand, but it is among the most influential books of my life. But Tanizaki delves into Asian aesthetics as they once applied to daily life. And this is really what I am getting at here. This quality of the humdrum of daily life (a term Nick Pemberton used in an article recently). The humdrum suffocating dullness of western society today.

“Were the Nō to be lit by modern floodlamps, like the Kabuki, this sense of beauty would vanish under the harsh glare…( )The darkness in which the Nō is shrouded and the beauty that emerges from it make a distinct world of shadows which today can be seen only on the stage; but in the past it could not have been far removed from daily life. The darkness of the Nō stage is after all the darkness of the domestic architecture of the day…( ) A knowledgeable Osaka gentleman has told me that the Bunraku puppet theater was for long lit by lamplight, even after the introduction of electricity in the Meiji era, and that this method was far more richly suggestive than modern lighting.”

Tanizaki

Garnar Eide Einarsson

Tanizaki writes a good deal about darkness. The darkness that is touched by candlelight. The way gold leaf holds light and ghosts large rooms with uncanny afterglow. And the discussion of No Theatre is very significant here, I think. For films that took that linear model, the expository text, the plotted story — this was the film that took to the improved technology of lighting. When Auerbach in his famous essay in Mimesis talks of the King James Bible in opposition to Homer, this *IMR* model Burch posits is Homer. While what Tanizaki describes in classic Japanese Tea Rooms or No Stages is the King James Bible. As Auerbach notes, the voices in the Bible, especially of God, just drop in out of nowhere. There are huge leaps of time and space. It is said it took forty weeks to reach the mountain…or forty years….and thats it. The reader learns nothing of what else happened in those forty years. It remains in darkness, in shadow.

“…the fertility rites of the Dying God contain the intuitive poetic understanding of that ego-rhythm which must be deliberately made use of in all creative work: the rhythm by which the ego’s ordinary common-sense consciousness voluntarily seeks its own temporary dissolution in order that it may make contact with the hidden powers of unconscious perception.”

Marion Milner

Guardian head, 13th century Japan.

I think that on some level all creative activity naturally seeks darkness. And darkness means silence in this respect. There is that idea of emergence, which it seems is sort of popular now for some reason, but its true in writing that one must wait for the solution to emerge. I use the word solution because I’ve been feeling recently that in a way the creative act is a solution, even if there is no problem. Perhaps as I wrote about illustration being a solution to an aesthetic problem, the non illustrative and corollaries is a solution without a problem. In any event the contemporary malaise and anxiety of the humdrum, of the eviscerated sociality of western cities and towns is linked to the over illumination, the noise, the refusal to allow mystery or ambiguity to exist for very long. And it is covered over by these increasingly obsessive micro behaviorial ticks. As I drove through Scandinavia last week, and through Europe a year ago, one is assaulted with advertising (far worse in the U.S. in fact) and with packaging. And maybe that sounds odd to say, but the incessant need to UN-package everything. Literally everything. One wades in a sea of plastic tags, and snipped box corners and used cups and straws and shrink wrapped everything, anything. In markets now vegetables…individual parsnips for example, are wrapped in plastic — presumably to protect them from dirt (you know, the stuff they grew in). It is constant, too. I love long drives alone. I love them with my family, too, but when one wants to write the solitude is nice. But the packaging industry has invaded consciousness, much as a model of the world created by cinema has invaded our consciousness.

Michael Eastman

Allow me on more, slightly longer, quote from Burch…

“For years certain Marxist critics and film-makers—-in Great Britain, especially, but also on the continent and in the USA—- have assumed that the ‘alienation’ eflect was inevitably illuminating and liberating, that anything which undercut the ‘empathetic’ power of the diegetic process was progressive. To be reminded that the scenes unfolding on stage and screen were artifice, to experience any mode of ‘distantiation’ was for an audience to be made able to think the textuality, to read the dialectics of the production of meaning, etc. I believed this, and still do so in the appropriate, slightly elitist context to which the idea is still pertinent. But it is beginning to appear to me today that United States television——more ‘advanced’ in this respect than any other, save perhaps that of Japan and Latin America, and now Italy, alas——mobilises a number of strategies whose, cumulative effect is to induce a certain disengagement, a certain feeling that what we see—-no matter what it is——does not really count. Distancing, in short, has been co-opted; it has found a place among the panoply of weapons available to the ruling class of the USA to depoliticise, demobilise the working masses (ethnic and racial divisions, geographic distance, overconsumption, etc.).”

Picnic (1955, Joshua Logan, dr.)

Daily life in the contemporary West is, additionally, ever more infantile. Children cannot imagine a world existing beyond what is directly in front of them. The modern audience sit in front of TV or in cineplexes, and are allowed to view the world as the children they once were. Or, rather, as children for the first time; at least the childhood they imagine in that nostalgic flashback sequence of their lives. If Americans (in particular) love the 50s (and now a fantasy 70s, and a fantasy 80s) it is because they are embracing an obvious studio managed imaginary nineteen fifties. And yet, I think this is partly what accounts for the enigmatic and disruptive quality of Douglas Sirk’s films. One of the outliers from the fifties is Josh Logan’s adaptation of William Inge’s Picnic (1955). And I say outlier because Logan was never received in later years as any sort of auteur, nor was he viewed as a prestige director or secure financial bet. He was, in a way, a little bit of all three. Logan was a mildly elitist director without bad taste, but possessing little taste at all, really. But he had a nose for those projects that were borderline prestige, but still felt aimed at an educated audience. As Robert B. Ray notes, the most successful directors of the mid fifties were all bete noirs for the Cahiers critics. William Wyler, Fred Zinnemann, George Stevens… these were the characterless technicians of middle brow taste. Logan was almost that, but he was saved, slightly, by an instinctive sense of the perverse. He was not a great director of actors, but this is probably why Picnic has the disruptive quality that it has. Everyone is a bit too overwrought. Of course the text of William Inge provides ballast. For Inge came out of the same basket as Theodore Dreiser. This was that mid western American realism that was in fact a far more almost Biblical morality play. It was the King James Bible even if it thought it was Homer. If made today the overwrought sexual terror would be ironized and cleansed– while telling itself the opposite. In fact, in retrospect Picnic feels acutely insightful — and Logan was probably (because of his lack of real vision or taste) the perfect director for it. I say insightful not in terms of theme or message but in the uncanny feeling that Hollywood was making a story about itself. It was not making Inge, really, though Inge provides a kind of inadvertent gravitas.

Daniel Zeller

It is interesting that at the end of his book, Burch quotes Hannah Segal (on Klein)….“The shift from the paranoid-schizoid to the depressive position is a fundamental change from psychotic to sane functioning.” This is the child at around four months. But I have written on this before, (http://john-steppling.com/2017/10/blunt-force-trauma/)

The idea that nothing matters is probably more complicated than Burch sketches it, but I think he is certainly right.

Michael Wood recounts a story in a discussion of Dryer’s Passion of Joan of Arc …

“Dreyer later said he wished he could have made this film with sound, but the silence of this work has an extraordinary eerie quality, and tells us something about silent films in general. The French surrealist poet Robert Desnos once quoted an anonymous friend of his as saying that the old cinema was not silent (mute in French); it was the spectator who was deaf.”

Wood also alludes to Burch’s book….“…commercial films have overwhelmingly attempted to deny that the shadows are shadows, to replace the expressive possibilities (Virgina) Woolf evoked with an old fashioned and all consuming illusion of life.”

Postcard, late 19th century. Polk Co. Minnesota.

What is being said here is that this system of cinematic grammar or language is one that insists on a very specific single gaze of the camera — everything works off of that. And that this in turn implies meaning because the viewer has come to associate and remember certain syntactical sequences. Like children learning a language. And this Hollywood system (it didn’t originate in Hollywood but it was perfected there) delivers an ideology, and one that reflects the period in which it was perfected (the 20th century of American imperialism and Capital). Godard and Jean Marie Straub have worked to denaturalize this system, to help disrupt a viewership that now sees the world this way. And beyond that, the shadows Tanizaki speaks of are removed the same way shadows of meaning are removed in this hegemonic film syntax. And it is not random, any of this. The tendency to dominate is historical, and this IMR (per Burch) can also be called the aesthetic regime of Capital. It infects everything. It also works to implicate engineers and designers of almost everything. That irritating plastic zip lock is the vision of a design team that have been imprinted with a certain way of looking at life. It is not only economic effectiveness, it is aesthetic ideology. The ugly design of a town center is reflective of a learned accommodation to the gaze of the authoritarian. The acceptance of this becomes very complicated, I think. For it requires repression and denial. Which is why that paranoid-schizoid position is significant. Now Straub and Danièle Huillet are radical but also problematic in many ways. But then so is Godard, but perhaps less problematic. But along with a handful of other directors they made films that challenged the IMR. Not every film from any director does this, but some films. If you go back to Lang’s German films, the Mabuse films, there is a sense of shadows returning. Those are psychoanalytic examinations of conformity and class and of paranoia, of course. Antonioni made films that excavated forgotten aestheetic ideas. So did Pasolini, at least in some of his work. So did Bertolucci, again, in *some* films. And Bertolucci is important because he really sensed the way architecture was collated with fascistic emotions and ideology. The ideology of the wall, the ideology of the window and the entranceway. Nobody ever did that as well as Bertolucci.

Aurelie Nemours

Juhani Pallasmaa wrote a very interesting book on architecture and vision. And he points out that peripheral vision is stimulated in places such as the forest. And that our pre-conscious perceptual realm, that outside of focused vision, is one of enormous importance evolutionarily speaking. And he suggests that the lack of concern in architects for peripheral fields is the reason contemporary building tends to make us feel like outsiders. And this is true for the ruling elite who commission this architecture. Peripheral vision tends to be inclusive and the focused gaze tends to exclude. And this is related to that sense of how subjective camera experiments never quite work. They tend to make the viewer an outsider and remove the safety of anonymity that IMR provides. This is but one paradox of western immersion in this IMR. And I think, as I said above, that the privileged perspectival gaze is coupled to moral superiority….for it is hierarchical at its core, and it served to instill a demand for obedience in the populace. The rise of ocular technology, from microscopes to movies, has only reinforced and intensified this privilege. Seeing what cannot be seen with the human eye is one of the strongest motifs of the 20th century. The conquest of the unseen. The conquest of shadows.

Pallasmaa notes also that shadows make depth and distance ambiguous and invite unconscious peripheral vision and tactile fantasy. The ascension of over illumination has created space without refuge in the West. And such loss of psychic refuge results in a kind of mental fatigue. And this, I think, is felt everywhere in the West today. Things that should not be exhausting are exhausting. Couple that to the fact that people must work longer for less money and the resulting fatigue is now reaching a state of the pathological. We walk streets that are the opposite of inviting. Everything feels and is fortified against us. There is a ubiquitous sense of threat coming from the way space is organized.

“We have lost our sense of intimate life and have been forced to live public lives, essentially away from home.”

Luis Barragan

Vincent Desiderio

Barragan was one of the architects of mystery and inclusion. He also derided the over use of large windows that he felt robbed structures of secrecy. In gothic cathedrals, as in Egyptian temples from the Pharaonic era one is met with an acoustic shadow world. The silence is one of memory. Even entering homes built a hundred and fifty years ago it is striking how the design limited noise and light. And this means also that something slows down. The emphasis on speed converges with noise and too much illumination. That cities now prevent people from seeing the stars is a profound loss rarely mentioned. Eileen Gray notes that architects tend to draw up plans that are designed to look good from the outside. They do not design for how it feels to be inside.

“Reification is the apprehension of the products of human activity as if they were something other than human products – such as facts of nature, results of cosmic laws, or manifestations of divine will’ Reification implies that man is capable of forgetting his own authorship of the human world, and, further, that the dialectic between man, the producer, and his products is lost to consciousness.”

Peter Berger, Thomas Luckman

The hegemony the medium of film, and TV, means the hegemony of a certain kind of looking. Sartre went on at great length about ‘the look’– and this oracular principle in cinematic narrative expanded by a natural affinity to the ideology of the ruling class after the Industrial revolution. The look, the gaze, and anything that made looking easier was valorized. Or rather anything that helped identification of what was being looked ‘at’ was valorized. The well lit stage, the surveillance aesthetic, the facial recognition myth that people are now conditioned to want to believe. So deeply engrained is this notion of identification of the *other* that life has gradually but inexorably gravitated toward accommodation of society as one vast line-up. We are to stand in barren space, under bright lights, and in a posture of supplication. For life is an interrogation. Space itself is the interrogator. The jurisdiction of technological reproductions of ‘the look’. And the fall out is that time is used up with the pointless unpackaging of not only parsnips, but ourselves.

Charles Goeller

“Indeed, the job killers have already arrived. Foxconn, the world’s largest manufacturer, responsible for an estimated 50 percent of all electronic products, is currently replacing assembly workers at its huge Shenzhen (China) complex and elsewhere with a million robots (they don’t commit suicide in despair at working conditions).”

Mike Davis

How one learns to stop *looking*, but to start seeing is a key to an emancipatory aesthetics. It’s not what is being look at, it’s how you do it. Memory, said Merleau-Ponty cannot be separated from the body. A coercive insistence on certain physical norms, and the sadistic stigmatizing of any heterodox thinking, has insured a society in the West, certainly in the U.S., in which voices coming from outside the emotional and psychic panoptic landscape will be shunned. The U.S. is a society of shunning, in fact, a society that derives pleasure (denied it in so many other areas) from humiliation — public shaming and scolding is given cover by a therapeutic apologia that justifies all as part of personal growth. My sense is people cannot articulate their demons, cannot and will not read anymore, or will not read anything of any difficulty, for reading itself is a kind of shade or shadow in the mind — a place from which ideas and feelings of autonomy emerge. One must sit as a child, as adults sit in their cars, eyes forward, with reassuring glances in the read view mirror, and read the signs. Read the instructions. And watch the lights…green or red.

“…the emotional dilemma of the schizoid thus: he feels a deep dread of entering into a real personal relationship, i.e. one into which genuine feeling enters, because, though his need for a love-object is so great, he can only sustain a relationship at a deep emotional level on the basis of infantile and absolute dependence.”

Harry Guntrip (Schizoid phenomena, Object-relations, and the Self)

The destruction of creative energy runs alongside the erosion of learning. Those who think independently are viewed with suspicion today. This really is the new Inquisition, the new witch trials. And it is significant that this film language so in ascendence is one that grows more infantile each year. And I sense CGI as a form of over-illumination, actually. It serves the same purposes. And the literal and figurative suicides that are spiking globally are viewed as the normal cost of doing business…suicide as breakage. Write it off.

Dr. Mabuse The Gambler (Fritz Lang, dr. 1922).

As always, donations to this blog was welcome and I thank those who have already donated. JS

Uma pequena sugestão: leiam, do filósofo Vilém Flusser, “A Filosofia da Caixa Preta”.

Brilliant! You well describe the modern malaise and it’s relation to cinema and advertising. Everything is cheapened, intimacy and empathy are curtailed, anxiety increases, and a schizoid quality permeates. Just look at how many channels the typical TV consumer is bombarded with, and the low quality of so much programming that dominates. People internalize the melodrama of film and the emotional patterns and limitations of movies, which are all based on tried and true formulas and sell conflict. The visual detracts from the intellectual, the act of thinking.

i love flusser. I quote him here…but a few other places too http://john-steppling.com/2015/09/you-will-not-be-by-that/

I enjoy your philosophical romps but I find myself disagreeing with every explanation of your spot-on observation that “everything touched by humans living under Capitalism, registers as ugly,” which seems unassailable. The attacks on montage, fear of darkness, 50’s cinema, contemporary ironic disassociation all seem besides the point and even simply wrong.

“Seeing is a key to an emancipatory aesthetics,” that’s exactly what the distancing aesthetics of “elitist” cinema was intended to do. Burch (at least in the text that you quoted here) is wrong. He’s conflating completely separate things: disassociation and ironic detachment. Today’s nihilism is to my mind more related to the conceptualist stance. It’s not so much that everyone is producing their own movie but rather curating their own private museum. Movie production is still work, after all.

Seeing was also precisely what much of 50’s cinema intended to do in its social commentary and why there was a witch hunt in Hollywood to silence it. Not sure how this can be overlooked in this context.

Re: the montage: Breton thought of the join as where the poetry of cinema occurred.

And finally, the least problematic thing about the ziplock is that they are annoying.

I think you are looking at all of this, or so it seems, out of context. I don’t know what this means….”“Seeing is a key to an emancipatory aesthetics,” that’s exactly what the distancing aesthetics of “elitist” cinema was intended to do. Burch (at least in the text that you quoted here) is wrong. He’s conflating completely separate things: disassociation and ironic detachment. Today’s nihilism is to my mind more related to the conceptualist stance. It’s not so much that everyone is producing their own movie but rather curating their own private museum. Movie production is still work, after all.”

People must create a narrative. If that private movie includes a museum, then fine. But the sense of people manufacturing a movie is my point. It is replicating the entire gestalt of filmic reality, too. People sample, I think, and identify with the subject position of Hollywood executive, but they most certainly are in the screen business, psychologically. Im not sure why that is even contested.

Capitalism makes life ugly. And everything it touches is in the interest of ugliness. Trying to find exceptions doesnt bely that. There is always aesthetic resistance within such systems. And what attacks on 50s cinema, or ironic detachment ?

But I think these are pedantic remarks and weirdly missing the point. And oddly, I find myself disagreeing with everything you said. Funny that.

But this is the problem with fragmented observations. Its also why finding exceptions to what are by necessity sort of generalized notes, becomes Burch is arguing often it seems to me, against Breton.

I have to say, on my part, that upon reading this latest post, I sensed something of my own nausea beginning to be articulated. This nausea that I feel while traveling, especially by car indeed, be it during transit or in the heart of a town. France, since this is where I live. A general feeling of doom permeates every building, street, shop, face. Every nook and cranny likewise. And it reflects back in a lack of complex and demanding art. An art out of proportion or out of joints, wading in ambiguity. And when I use a word like complex and ambiguous, it is only as complex and ambiguous as it should be. To measure up to reality. And no amount of long-term TV series seem to belie this, when it could.

Great remarks on the need for shadows. It brings to mind a sensory approach to history. You have to feel this past – there were flickering candles, which is a special quality of light, impossible to simulate. Altar in churches. Way before that, the torch, dim and feeble, with its burning fats, producing a considerable amount of black smoke – a world enshrouded in complete darkness. A world of menace and impending danger. And it makes me think : to what extent is this quality of light necessary and compelling for producing great art and thinking ? You have to think of writers of a not so distant past, writing in the spell of a flickering candle. Hardly seeing. Lots of moving shadows all around. It certainly had its influence upon some sort of thinking/writing. This quality of things left in the dark, in the surrounding environment but also, then, part of the ambiguity of a specific sentence or construction. And this difficulty of apprehending the real becoming part of the work. And a sense of beauty. And the candle or even gas lamp keeps declining, one has to rekindle it constantly. Trim the wick. To what extent is thinking and taking action dependent upon lighting ? Think people writing, playing, eating in near obscurity. And lighting, be it candles, was costly, for some. Think people who had to hurry before they were out of light. So perhaps it also had its influence upon time and measure, so that it was used much as a hourglass might be. And it brings us back to the cave paintings and their unsurpassed beauty. For me the pinnacle of painting. Done in darkness, with a small amount of flickering light.

Regarding architecture, only a small and perhaps useless speculation, but it might have to do with measuring standards for both space and time that came in the wake of the Enlightenment (funny how it is precisely this line of thinking which comes right after my previous remarks on shadows).

The meter system, agreed upon in 1793 is a case in point. The old measures were based on parts of the human body, hence as differentiated and diverse as human cultures. Then it becomes one ten-millionth of the distance from the equator to the North Pole.

It may be that past constructions (including, obviously, modest ones) seem nicer to look at since they have built-in irregularities, sort of. They were built according to measuring systems for which the standard was actually a variable, this or that part of the human anatomy. I also suspect greater care was spent thinking how a specific building might blend into the surroundings, before the advent of modern urban planners which seem blind to how it all fits together. They can’t see the forest for the trees. “That cities now prevent people from seeing the stars is a profound loss rarely mentioned.” I think it sums up what radical politics today might stand for : it’s part of a common use-value that’s being robbed from us. A commons which is as important as water.

@anthony:

The sensory history reveals much, I think. I often wonder at the world that very early homo sapiens. And then as you write, the world before electric lighting. I think we have lost a lot with the obsession to illuminate things.

And indeed those small irregularities provide something that is linked to basic human movements. I remember when they repaved the old stones in the central square in Krakow. It was horrifying and literally everyone felt it. The sense of loss. Of the beauty of things hand cut.

John, I also have to point out how strong it is when you make sudden incursions into the realm of literature within some of the essays (making the most of this form), with bold and gripping images, such as :

“We are to stand in barren space, under bright lights, and in a posture of supplication. For life is an interrogation. Space itself is the interrogator.”

(…)

“The fall out is that time is used up with the pointless unpackaging of not only parsnips, but ourselves. ”

I’m pleased to see the Pallasmaa book mentioned – Eyes Of The Skin, is it ? It’s precisely this type of sensory anthropology I’m researching and delving into further and further.