Ad Reinhardt

“When premessage expectations are disconfirmed (as in the case of a person or a software product admitting a bias or a shortcoming), the receiver of the message (in this case, the user) perceives the sender (in this case, the software) as unbiased (discussed in Stiff 1994, p. 96), which is a key contributor to credibility…”

B.J. Fogg

“The vulgar crowd always is taken by appearances, and the world consists chiefly of the vulgar.”

Niccolò Machiavelli

“In 1977, state district judge, Jack Love, noticed two items in a local Albuquerque, New Mexico, newspaper. The first was an article about an electronic identification tag, invented at the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory. The tag was implanted under the skin of livestock. The second was a Spiderman cartoon wherein a villain clamped an I.D. bracelet on Spiderman that tracked movement. Judge Love subsequently convinced a technician to construct an anklet, and in 1983 three offenders were sentenced to wear the device as a condition of probation. This was the “live birth” of Electronic Monitoring. Within six years, hundreds of units were being used in the United States. Today,an estimated 110,000 – 120,000 monitoring units are deployed on a daily basis in the U.S.”

Robert S. Gable

“…in the electronic age, data classification yields to pattern recognition (…) men resort to the study of configurations, like the sailor in Edgar Allan Poe’s Maelstrom.”

Marshall McLuhan

The Globe & Mail in Canada ran a story on smart phones this month: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/technology/your-smartphone-is-making-you-stupid/article37511900/ One of the primary thrusts of this piece was that electronic media is cutting attention and is addictive. The connectedness of contemporary digital life is actually disconnectedness. Well, that is my conclusion — that last part. It is certainly intensifying alienation, but how much this has to do with Capitalism and how much with the inherent properties of electronic communication is the question.

Emmanuel Monzon, photography.

“The impact of social media has been huge,” a second psychologist told me. “Social media has completely shaped the brains of the younger people I work with. One thing I am often mindful of in a session is this: I could be five or ten minutes into a conversation with a young person about the argument they have had with their friend or girlfriend, when I remember to ask whether this happened by text, phone, on social media, or face-to-face. More often the answer is, ‘text or social media.’ Yet in their telling of the story, this isn’t apparent to me. It sounds like what I would consider a ‘real,’ face-to-face conversation. I always stop in my tracks and reflect. This person doesn’t differentiate various modes of communication the way I do . . . the result is a landscape filled with disconnection and addiction.”

Adam Alter

There is no question that digital electronic media has altered consciousness, but at the same time there is kind of inflating of its importance. And perhaps this is the disturbing aspect of the topic. B.J Fogg’s book Persuasive Technologies has become a kind of go-to manual on the basics of information technology. But reading it one is struck with just how rudimentary are the observations. There is plenty of other work written since, but none of it feels as if it is mining the philosophical (nor the political) implications in things such as social media and online advertising. And it may only be that I have a sort of personal aversion to discussions of technology because they so often fail to escape the language of technics, the grammar and vocabulary that been built up now for decades.

Julio César Morales

It was Hitler who wrote that the strong leader (sic) must “be popular and has to adapt its spiritual level to the perception of the least intelligent….Therefore its spiritual level has to be screwed the lower, the greater the mass of people which one wants to attract.” Whatever the potential some see in the internet and electronic information, the reality is very grim and as the Globe & Mail article pointed out, the citizens of the West today have the attention span of goldfish.

“What do they [consumers] make of what they ‘absorb,’ receive, and pay for? What do they do with it?”

Michel de Certeau

“With its speculative (metaphysical) vocabulary, philosophy is itself a part of human alienation. But the human has developed only through alienation.”

Henri Lefebvre

Pablo Palazuelo

Now, as a kind of side bar observation, de Certeau is routinely described as anti Marxist and somehow the opposite of the Frankfurt School. And I think that’s not really accurate. It may be that de Certeau’s biggest contribution comes in how he views creativity and the ways it manifests itself, even in the heart of consumer society. His politics are essentially daft, but that isnt to say he isn’t worth reading. In any event, the questions surrounding smart phones are important if only because there is no denying the extent of their monopolization of time and attention in the populations of the North America and Europe (and everywhere, really, but not as acutely as in the affluent West).

I am constantly made aware of the feeling (and I hear this from other writers all the time) that everything has begun to feel like a cliche. It is the pervasive sense of familiarity. And of course this is partly, if not largely, the result of the internet and advertising.

“The archetype is a retrieved awareness or consciousness. It is consequently a retrieved cliché…Civilization has to be recollected by every citizen. Education, whatever guise it takes, is retrieval of the archetype…Whenever we ‘quote’ one consciousness, we also ‘quote’ the archetypes we exclude; and this quotation of excluded archetypes has been called by Freud, Jung and others, ‘the archetypal unconscious’.”

Hugh Kenner

Eduardo Chillida

McLuhan was convinced that print media was foundational for modern conformity, and in fact the modern state. Homogeneity is foundational to the idea of the liberal individual. But this sense of the familiar was always there, just not working as a part of a system of domination. The most pernicious aspect of the internet is not the addictive aspect (more on that below) but the mystification of what we know to be familiar. For the familiar is not menacing and psychologically debilitating, except that today that is increasingly what it has become. I forget who it was that pointed out that the forger of classic paintings must always know more than the artist he is forging. This, of course, raises the question of what is meant by knowing.

“The power of technology to create its own world of demand is not independent of technology being first an extension of our own bodies and senses. When we are deprived of our sense of sight, the other senses take up the role of sight in some degree. But the need to use the senses that are available is as insistent as breathing – a fact that makes sense of the urge to keep radio and TV going more or less continuously. The urge to continuous use is quite independent of the ‘content’ of public programes..`{ } Once we have surrendered our senses and nervous systems to the private manipulation of those who would try to benefit from taking a lease on our eyes and ears and nerves, we really don’t have any rights left.”

Marshall McLuhan

I have thought often that Hollywood film and TV are operating on a pattern recognition basis. A friend of mine, a screenwriter with whom I work, noted this recently, in terms of genre. For the stories out of Hollywood are not really stories, they are templates for stories, and the audience, which is so familiar with such genre product, quickly identifies the genre, and then the sub genre, and usually predicts (based often on what they intuit the budget of the project might have been) the outline or pattern of the film.

Hugh Kenner

Walter Benjamin saw the modern urban landscape as one of shock. That modern city life was discontinuous and this lack of relation between part and whole, or just between one action and the next (like the assembly line) were different in quality from the elements in storytelling. But Benjamin saw the gambling den and the crowd as representative of this discontinuity. In the gambling hall each game is unrelated to the previous one. Each hand or roll of the dice has nothing to do with the previous roll or the next. They are not meaningfully interconnected. What strikes one as interesting in this model for modern urban life (and its important that faces appear and disappear faster than at time in history) is the idea of addiction — for gambling is, in contemporary thinking, a form or addiction (or can be, lets say). But this raises issues about the nature of addiction. The addiction to smart phones and screen input is both like gambling in a sense, but also unlike it. And neither share much in common with, say, heroin addiction. Never mind that the physiological responses may be similar or even identical — the metaphysics of each undertaking is different. But it does, whatever one thinks of the definitions for addiction, suggest that modern urban life created the preconditions and forces that would lead to addictive behavior. And loneliness is at the top of the list.

The mechanisms employed, psychically, to defend against the shocks of modernity created a kind of subliminal anxiety and drudgery (per Benjamin). This was the tragic contradiction of the progress signaled by the Enlightenment. The advancements in computer and digital technology have created a both a kind of refuge from shock, and introduced a new register of shock.

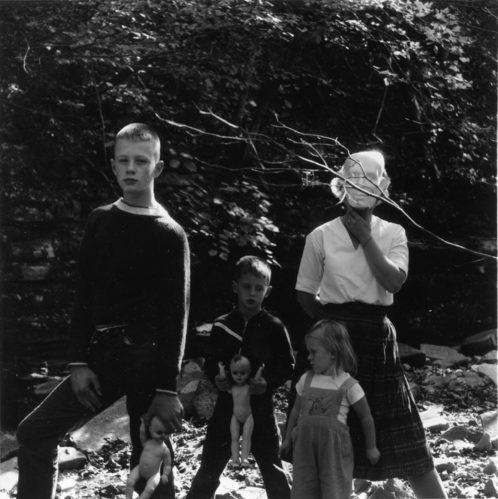

Ralph Eugene Meatyard, photography.

“Computers can do better than ever what needn’t be done at all. Making sense is still a human monopoly.”

Marshall McLuhan

“The bourgeois whose existence is split into a business and a private life, whose private life is split into keeping up his public image and intimacy whose intimacy is split into the surly partnership of marriage and the bitter comfort of being quite alone … is already a Nazi … or a modern city-dweller who can now only imagine friendship as a ‘social contact’: that is, as being in social contact with others with whom he has no inward contact.”

Adorno

The moment in which McLuhan arrived (the sixties) was already one in which the collective — at least those under thirty — was questioning notions of scientific rigor and classification. The hippies wanted nothing to do with instrumental thinking. There was also, post Vietnam, a feeling shadowing the populace that technology was changing and the moral compass of corporate America — already throughly distrusted — was going to lead people over the edge. This was a time of LSD and Esalen. It was Scientology and Werner Erhardt. Now I was living in California at the time, so my perspective is no doubt skewed, but there was a collective mourning after Vietnam (narcissistic to be sure for few mourned the dead Vietnamese) and also a kind of apprehension. All those post Vietnam noir films captured some of this (Who’ll Stop the Rain being the best probably). It was also the very front edges of computer promise.

“The Nazi regime’s extreme, coercive demands on attention oblige us to consider the relationship between control over one’s attention and human freedom.”

Tim Wu

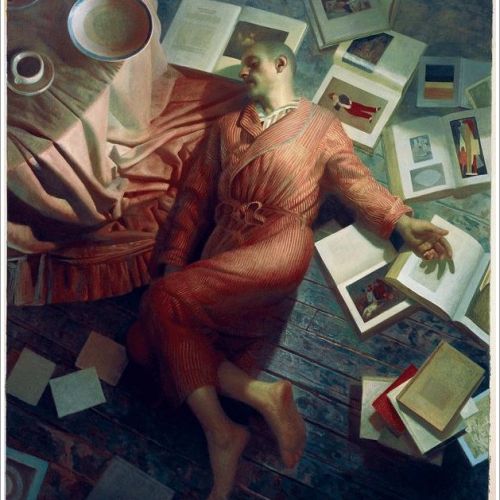

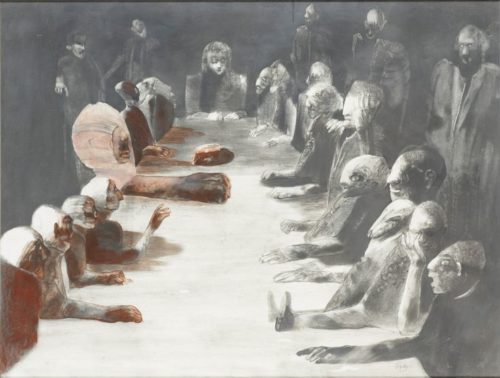

Vincent Desiderio

“God is boundless. If nature and the form of the universe reflect his reality, then it too is boundless. A boundless region has no center . . . Hence the world machine will have its centre everywhere and its circumference nowhere.”

Nicholas of Cusa (1440 AD)

“Not only will the Internet tend to divide people with different views, in other words, it will also tend to magnify the differences.”

Nicholas Carr

McLuhan saw alienation occurring when language is estranged from reality. Hugh Kenner (who I once saw lecture, by sneaking into his class at UCSB ..way way back around 1970) writes in the introduction to his book on Flaubert, Joyce, and Beckett that…“This means that we have grown accustomed at last not only to silent reading, but to reading matter that itself implies nothing but silence.” It is like the language of mathematics, but it is also the language of computers. People read and text a discourse of silence. Typographic culture evolved into the voiceless. Computer language, code, is not even that. It is pre voice, or perhaps post voice.

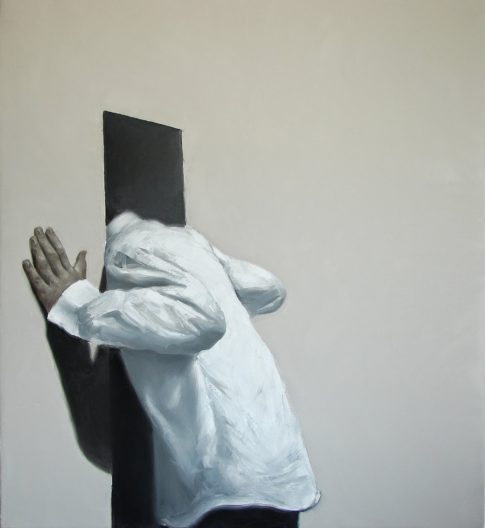

Mircea Suciu

So, all the discussion of shrinking attention spans and anti social addictive behavior, while true, and it IS absolutely true (well, the addiction part is open for debate),the far more interesting discussion, I think, is about the nature of expression and experience. And about the erosion of speech. And here McLuhan was rather prescient. His ideas on oral space, or what he called acoustic space, was, perhaps unsurprisingly, rather like all the great classicists …Kenner and Norman O. Brown, F. R. Leavis, and Calasso, and Empson et al. For the return of a certain primitivism …whose start one sensed with the sixties… reflected a sensibility more in tune with antiquity. Or, with modern ideas of what antiquity looked like.

“By 1780 the mind of Europe had excogitated the Dark Ages, the middle classes, the mercantile spirit, Virtue clothed in Roman togas, enlightened Frenchmen, humorous Englishmen, the past as object of knowledge, the future as arena of betterment, polite society, universal Reason, improving books, useful knowledge, facts and the duty of collecting them, opinion and the need to guide it, sobriety the leveler of all things, and Posterity our concern for whose interests justifies (does it not?) so much unstillness. ”

Hugh Kenner

Sandro Botticelli (detail : Christ Child From The Madonna Of The Pomegranate).

The novel, as Kenner notes, operated on twin assumptions; verisimilitude and plausibility. The apex of this form was, for Kenner, found in Jane Austin. The apex in the sense that the form had reached self parody. And here is where Flaubert stands as (per Kenner) the first of what he calls the stoic comedians. Without going into great detail of Kenner’s theory, the germane point here is that Flaubert and after him Joyce, were meticulous craftsmen who carried writing forward into a kind of reductio ad absurdum. But that was their genius, in a sense. When Kenner writes of Pound, he sees the importance of his poetry in the erasing of temporal signposts. Pound was radical in the sense that he was to writing what those cave paintings in southern France were to visual art. Joyce simply adjusted expectation (the adverbial phrase comes before the object, often, for example) and in so doing he is straddling speech and text, and orality becomes something other than it had been before.

People no longer speak of literature this way, if only because they mostly don’t talk of literature at all but rather of films and television. And this reminded me of the Aziz Ansari story this week. Never mind the details which are well known. One thing stood out for me and that is the language of the accuser. In the N.Y Times story, which was very critical of the accuser, actually, we learn this...”We are told by the reporter that the woman “says she used verbal and nonverbal cues to indicate how uncomfortable and distressed she was.” Now who talks like this? Non verbal cues? The answer is that nobody *talks* this way. But it is, in some situations, apparently how people write. And look, maybe some people DO talk this way, because what do I know. This is the nadir of the entire tsunami unleashed by the Weinstein and Spacey revelations. And it is The Crucible but written in a voiceless spread sheet therapeutic prose (cross pollinated with Puritan rigidity, it goes without saying).

Titian (1543, detail Ecce Homo).

“Medieval and ancient sensibility now dominates our time as acoustic and multisensory awareness displaces the merely visual.”

McLuhan, 1988

So the late modernists that Kenner was so fond of were re-inscribing something that was both lost and something that felt menacing. And this is felt in the dialogue of Pinter, and in Beckett, too, in a different way, and it coincided with a rise in abstraction in the visual arts. The screen world of digital media gives the illusion of acoustic space, but it is quite the opposite in fact. But then, there are screens and there are screens.

Albel Segura Sanchez

George Steiner, archly conservative, still saw the essential nightmare of Nazi Germany in the way language became only cliche. But cliches today have taken on a new form.

“Lyotard’s definition of the event as a force that resists the processes of signification within a system is similar to Derrida’s critique of the structuralist project in his article ‘Force and Signification’ (in Writing and Difference). Lyotard’s statement that ‘there is a dimension of force that escapes the logic of the signifier: an excess of energy that symbolic exchange can never regulate’ (Political Writings 64) echoes Derrida’s exploration of the possibility of a loss of centre within the structure, which opens up the destabilising dimension of play and chance (the dance of signifiers, the sliding of the signified, the impossibility to fix meaning).”

Karoline Gritzner

Masahira Fukase, photography.

The false return to antiquity today takes place with the citational cliche; the screen, computer or smart phone, is circulating an endless voiceless sub grammatical code. And each user is also involved in personal lexicography. This is the hidden dimension of the habituation of these gadgets. The compilation of scanned symbol, fragment, and personal meaning, or faux meaning. For while there is no center and no apparent boundaries or horizons, the reality is that the user is engaged with something closer to an endless tunnel — but also not very different from what Benjamin saw in the new urban life of his era. The shocks of discontinuity remain but the currency of the voiceless is a repressed surplus unconscious force (not unlike what Derrida suggests). There is an almost palpable angst expressed in smart phone compulsions. The accusations against Aziz Ansari were written for an online site that solicited such celebrity scandal. There is a compulsive reaction from various quarters, but all of it circulates what is nothing more than gossip. But the gossip of cliche ridden imaginations. And there is the subliminal suffering of all involved. The barely registering anxiety and discomfort of the discontinuous. For again, the new primitivism of social media, of smart phones and social media, is never more than a partial forgery of real emotion, let alone thought.

James Kelman

There never was nor is there now a *global village*. That is the dream residue of Imperialism and colonial fantasy. The sadism of class society, or global hierarchies of power remain, and private property and the consolidation of wealth is clearly enforced by militarism and coercion. But the fantasy, the mythology of McLuhan was not unimportant — if only because of the ways in which it was wrong. And his notions of acoustic space are prescient and insightful. But today, the masturbatory texting and constant repetitive checking on email or message are signs of dementia, of that very estrangement of language from reality that McLuhan noted.

And this segues into a sort of footnote on comedy and humor. I find that today more people laugh at what is, arguably, not funny than ever before. But comedy is very personal, too. Beckett and Ionesco augured the end game for comedy. Or for, perhaps, laughter. That this has not happened does not make it untrue. And with Beckett it is a language based comedy. Textual comedy, really. But is a Buster Keaton possible today? Was Keaton ever really *funny* ? Lenny Bruce was the auteur of modern spoken comedy. His stand up was always about his own tragic trajectory. And the closer he came to death the less funny he was. And his self awareness of this made listening almost unbearable. Richard Pryor did the exact same thing. For comedy today, it would seem, must be Swiftian. I have said the Danish comedy Adam’s Apples (2005) is the funniest film I’ve seen in the last twenty years. But I know many who watch it and never crack a smile. Tropic Thunder didn’t make me laugh once. But I know a dozen people think it was hilarious. So on this level, the laughter is of personal trauma somehow. Chaplin or Keaton were not personal in that sense. Pauline Kael once wrote, in a review I believe of Chaplin’s comeback film Countess from Hong Kong (1967) that if Cary Grant vomits out a ship’s porthole, its funny. If Brando does it, its tragic. There is a good deal of truth in this and it relates to the personal dimension of comedy. The comics from the old Vaudeville circuit, often Yiddish too, such as George Burns or Milton Berle were impersonal — they were, as placed within some continuum of comedic form, the Jane Austins of comedy (not in content, because there was always something very NOT careful in their verisimilitude and plausibility — but they still narrated a world according to those principles). By the time we get to Pryor, it is the Joycean. And today, that extra temporal Poundian or Joycean subject, that *voice* that is one character within a narrative, has been reduced to performance artist narcissism or to the court eunuchs extolled by mainstream media (Lena Dunham comes to mind, but there are dozens). Perhaps a James Kelman can be conceived of as Swiftian. At least the Kelman of How Late it Was How Late.

Roj Friberg

Of course a Berle or a Jack Benny or Henny Youngman were also sado masochistic. They were impersonal sadists. But to enact that role requires a certain gravitas. Seinfeld has no gravitas. Hence he is only a condescending prat, the guy you kicked on sand on at the beach who DESERVED to have sand kicked on him. The subject of comedy is vastly complex and I will write more on it in part 2 of this posting. For humor, and comedy to be discussed with any significance means one must examine laughter. And the laugh is a highly unpleasant topic. And the laugh is socially and historically mediated. I suppose that is obvious, really. What was funny twenty years ago might not, often IS not funny today. But again, what does one mean when saying something is funny? I laugh out loud at Pryor. But it pains one, too. The contemporary stand up phenomenon is less related to comedy than it is to public sacrifice. These are impersonations of beheadings or crucifixions. There is also always something volkish about visual physical comedy. It is why the historical final act of comedy was textual. Ernst Bloch pointed out the sincerity and honesty of the circus, but added there was also estrangement. Comedy on every level entails surprise. But there are varying degrees of surprise and varying kinds of surprise. Suspense is the withholding of surprise, though often this is counterfeit. Physical visual comedy has always struck me as containing something that lingered unpleasantly. An aftertaste. A bad aftertaste. Comedy does not cleanse. Nor is it redemptive. Curiously perhaps Bloch saw tragedy as no place for those who are too internal. It is social.

Gottfried Helnwein

Bloch saw circuses and comedy linked. He wrote too of the circus…“The tent-boats weigh anchor for a short time in the dusty cities. They are tattooed with pale green or bloodthirsty paintings in which votive pictures projecting rescue at sea disasters are mixed with those of the harem.” The magic comes from elsewhere. It travels on to another site. The estrangement of the comic is one of guilt, I think. Also of shame perhaps. A slight echo of shame. The guilt, though, is obviously tied up with the cruelty of laughter. I am not sure there is any kind of laughter that is not cruel.

As Adorno noted, there is laughter because there is nothing to laugh at. For Horkheimer and Adorno all jokes are dark and a deprivation, sadistic, and even if only indirectly they attack beauty. The best elevated forms of comedy are aware of this. Their laughs are there because theirs is a world in which beauty is a victim already. They joke at the wake of beauty and nature. For both Adorno and Horkheimer, true happiness is without laughter. The stand up comedy clubs dotting America are there as sanctuaries for those who cannot face the world. I suspect this is what is meant by escape for many. But this is an escape coloured by something socially rancorous.

“In the false society laughter is a disease which has attacked happiness and is drawing it into its worthless totality. To laugh at something is always to deride it…( ) Such a laughing audience is a parody of humanity.”

Adorno and Horkheimer

Damien Drew, photography.

Today, television comedy is pure pattern recognition. Both in text and speech — the actors adhere strictly to approved rhythms. And visually, and form. I mean TV sit coms still pattern themselves after I Love Lucy. That so much of TV product is comedy, well, in fact all Hollywood product contains disproportionate amounts of comedy, speaks to the deflected sadism of those who own the networks, telecoms and studios. Let them eat comedy.

“Narrative implies that someone is talking. It is an art that unfolds its effects in time, like music. It holds us under the spell of a voice, or something analogous to a voice, and (again like music) it slowly gathers into a simplified whole in the memory”

Hugh Kenner, Flaubert, Joyce, and Beckett: The Stoic Comedians.

Now, a final thought here on comedy. Chaplin is the outlier in a sense. I say that because one can find clips of Chaplin that feel as if they are not exactly comedy. Not exactly. I came across his fork dance, which Id seen before decades ago, on Menachem Feuer’s blog.

If comedy can transcend laughter, this might be an exhibit in that argument. Or maybe, if laughter can be redeemed, this is an exhibit for that argument.

And finally, as I was looking at the photography of Ralph Eugene Meatyard this week, for whatever reason took me back to his work, I came across this short paragraph by Guy Davenport.

“He was a lens grinder by profession, which meant he was short of free time. His evenings were apt to be taken up with teaching, lecturing, arranging shows, and he longed to read more and more. There were books in his automobile, by his equipment in his office. He had more hobbies than could be kept up with, especially those that involved his family; hiking, cooking, collecting the poetic trash that served as props for his pictures. One could usually find the Meatyards up to something rich and strange: making violet jam (or some other sufficiently unlikely flavor), model ships, fanciful book covers; listening to a superb collection of antique jazz, or to recordings which Gene seemed to dream up and then command the existence of, like the Andrews sisters singing Poe’s “Raven” (“Ulalume” on the flip side, both in close harmony). He had a recording of the wedding of Sister Rosetta Tharp. He has a loose-leaf notebook of thousands of grotesque and absurd names. He was a living encyclopedia of bizarre accidents and Kentucky locutions. One evening he turned up to tell with delight of hearing an old man say of the moving pictures these days that by God you can see the actors’ genitrotties.”

Guy Davenport on Ralph Eugene Meatyard

We haven’t filmed it yet, but we’re learning Chaplin’s fork dance for Dumb Puppy (the video element that’s been evolving). J. Depp did a take on it in Benny and Joon.

I submit that a baby’s laughter is not cruel (but also: why are they laughing? I think I say in Dumb Puppy, “for a baby, there is no such thing as funny.” Having witnessed the first laughs of my children, it was one of my favorite parts of being a mom.

The Diné have a ceremony to mark the baby’s first laugh. This goes into a bit. https://tazhiiyazhi.wordpress.com/awee-chideedloh-the-baby-laughed-ceremopr/

well Elizabeth….with twin 11 month old boys I wonder too….WHAT are they laughing at. Sometimes they both laugh really hard at something….utterly mysterious…but they BOTH think its funny.

Hugh Kenner’s Joyce’s Voices is one of my favorite pieces of literary criticism. The monoculture of the online world is in stark contrast to the rich world of polyglossia, of dialects, accents, world-views that Kenner unlocks in his slim book. Our digital simulacra is crude in comparison and incapable of embodying our human complexity. Yet, somehow our digital overlords have convinced us this is a feature and not a bug. The resulting mono-culture has been very good for business but bad for just about everything else.

I, too, thought instantly of the child’s laugh upon reading the statement, “I am not sure there is any kind of laughter that is not cruel.” And I will admit that when I read that “for both Adorno and Horkheimer, true happiness is without laughter”, this sentiment also struck me as untrue, though I admit I am not familiar with their writings regarding this exact train of thought. The sentiment itself seems to say little without context. What, after all, do they mean by “happiness”? And, it is also plausible that Adorno and Horkeimer never heard a certain kind of laughter before.

A child’s laugh (and there are some adults who can do it too, and actors train their bodies to be open enough to laugh again as the child does)–is a laugh of abandon. I wonder if the child’s laugh is mysterious because we are looking for the cause of it with our reason or our intellect? The child has not yet lost their full connection to their bodies as responsive beings, intimately connected with their environment, so their laugh might be a kind of impulsive, creative flow of connection between their body and all the stimuli of the environment open to them, NOT reason-based, as a laugh at a joke is. The child’s laugh is a laugh that comes from a body that still trusts the world–an open body. We socialize ourselves to blunt our emotions or not express particular emotions, and the truly open, healing laugh may be one of these expressions that we lose our capacity for because it simply requires too much vulnerability.

The child’s laugh comes from a vulnerable, open body. It is a laugh of sheer delight and joy–the pinnacle of happiness, no?–a joy in simply being itself. And it can be tragic too. Laughter and sobs are not far apart, physiologically speaking. And we know too well that oftentimes it is a “mystery” why the baby cries, despite all the needs we can think of being met. But our bodies–if we are at least somewhat embodied and empathic beings–our bodies are affected by the child’s cries. Somehow, we KNOW why they are crying because we feel their distress with them. Oftentimes after feeding and burping and changing, etc. have been tried and the child still cries, we hold them and hold them. We do not reason through the mystery, but our bodies find a way to ‘sit in’ the mystery, as it were. You say something about asking ourselves “what it is to know” earlier in this post, Steppling, and I would suggest that in this example, holding is knowing.

Anyway, i’ll admit I don’t know enough of adorno or horkheimer’s “happiness” to make any direct comment on it regarding laughter. I DO think that comedy is different than laughter, and that comedy facilitates a certain kind of laughter that I concede may not be “cleansing” or “redemptive”……but I’m not convinced that there is not a certain kind of laughter that can heal. I know a laugh that warms and makes the faces glow of those who hear it. This laugh can soften hearts and make grouchy folks set aside their differences for a moment. It is a laugh of sheer delight and openness in the body and it gives kindly to others. This laugh says, “I hear you, I see the situation, I am delighted to see and feel and sense a sort of impossible perfection that I can perceive in this moment.”……I am having difficultly describing this laugh, but it is the sound of a body experiencing something that the body almost perceives better than the mind does. It is not a laughter AT something funny, but a laughter OF joy and delight. Maybe it is rare….i don’t know, but i have heard it and i have felt it.

Tragedy is born to her whose laugh is extinguished. And yet, perhaps too, this laugh can only be heard because great suffering has been felt and know and processed in its turn too (??). I am unsure. But a child can laugh like this who has been thrust from the womb and discovers for the first time the wonders of the body and the world that we take for granted as we become mired in our reason and jaded by our experiences.

I will amend that comment to read no adult laugh …..but…..define child. At what age is that lost? Very young. Probably innocence is lost with the learning of language. My twins laugh and all that but its pre verbal. Its almost a different category altogether. I dont trust any adult laughter I have to say. I just don’t. And hence Im very suspicious of laughter overall. Certainly in contemporary society. But maybe always.

Define child…okay, i’m going to wing it here…..i suppose it is not an age thing, exactly, but tends to correspond to age. Some “children” do not have a childhood and must grow up very quickly to survive. I suppose the “child” i speak of, is the being that is responsive but not responsible–the being that is cared for but not caring for (though a child’s presence may warm or heal simply by being and teaching us things we have forgotten, but this is not “caring for”). The child is the seat of curiosity because everything exists for its pleasure to discover. The child as completely selfish in a selfless kind of way….innocent of judgement, open of body to scream and move and emote without injuring themselves…….I don’t think the child is completely lost with language, though parts of it might be. Maybe some of it can be regained.

I don’t know what to say in response to you not trusting any adult laughter. This seems a valid response, but i wonder what it means exactly. Maybe i am deluding myself or denying something when I speak of a laugh’s potential. Do I trust a laugh? I don’t know….i guess i’d have to think about that. Do I trust my own laugh? My own sobs? Even if i don’t understand them? Yes, yes, i think i do.