Robert Adams, photography.

“The dominant feature of psychological realism is its determination to be anti-bourgeois.”

Francois Truffaut

“…the human skin of things, the epidermis of reality, that is the primary raw material of cinema.”

Artaud

“Through style one infuses a film with a soul, and that is what makes it art…”

Carl Theodore Dreyer

I find that with the ubiquitous presence of screen media today, the paradoxical and ambiguous nature of acting and performance to be worth examining. And this ties in with questions of taste I posted about last time. Martin McDonagh’s latest film, Three Billboards Outside Ebbing Missouri was released over the holidays. It is McDonagh’s third film (feature length film anyway) and his most ambitious. McDonagh is an Irish playwright (though he grew up in London and holds dual British and Irish citizenship). Now McDonagh has had a pretty successful career as a playwright in the U.K. but was clearly and is clearly more attuned to film. His popularity always nagged at me when reading the plays (I confess I’ve not seen one) because they teeter rather too closely to whimsy and a kind of cuteness. But still, it also was clear that he had a native ability for writing. And when I saw In Bruges I was ready to dislike it, but found I liked it far more than I could have ever expected. And I need to explain that bit. I confess I never go to or watch comedies. Contemporary comedy feels neurotic and almost hysterical, and somehow narcissistic. When I watch the Marx Brothers or Chaplin or Keaton I feel I am watching something of an entirely different order to contemporary comedy. Even watching a Phil Silvers TV show, or Burns & Allen in those old half hour TV comedies, I feel something I know I cant find today. But McDonagh I think comes close. But I am not sure, at all, why I think this. In Bruges is whimsy, too, at times, but its witty as well. It is the best Colin Farrell has ever been. And its intention is limited. But in the new film (3 Billoards...) there is a sense of additional ambition, of a deepening awareness that it is taking itself seriously. And then, its not really a comedy. And that is what is vaguely troubling. Because it is not drama, either. And maybe this lack of definition, in terms of genre, is part of what makes it so convincing as a film. I say its not comedy, but I suspect it is perceived primarily as comedy. And that is telling.

Why Herr R. Ran Amok (Rainer Werner Fassbinder, dr. 1970).

I’ve always been a bit of two minds about Francis McDormand. For she straddles that line between hyper naturalism and something else. She is not really a naturalistic actress…and that is sort of the issue for me. What is her performance here? McDormand coasts through parts of the film by simply making clear her intelligence. In fact I cannot think of another actress, offhand, who exhibits intelligence so convincingly. Anthony Lane pointed out in his gushing New Yorker review that the title feels like a title for a photograph. And its true. It could be, as he says, Walker Evans, but also Joe Deal or a dozen others. And this film comes close to that territory of storytelling that is making fun of rural America. But it doesn’t. It is also, oddly, almost free of irony. Woody Harrelson’s cancer ridden chief of police is a genuine character. And a brief few scenes from Clarke Peters reaffirms his position as among the best of American actors today. And McDonagh is great with actors, it should be noted. Nobody is impatient, and nobody pushes for effects or asks for any particular response. John Hawkes (another very fine American actor, among the few) has a nice almost cameo as McDormand’s ex. They all watch the world around them. Peter Dinklage is riveting as the “town midget”. Again, McDonagh allows for intelligence to simply be presented. McDonagh trusts the intelligence of the viewer. But it is McDormand who is the focus here and she, maybe for the first time, never asks for a particular response, or to be liked, or anything. And her character’s grief has not made that character at all a better person. And this is perhaps what the film is about, finally.

Gommorah (Roberto Saviano, creator, 2014).

Suffering is not good for you, is not ennobling. But, there are things that remain troubling. Rural America is still rather too friendly and wholesome. McDonagh plays off the alcoholism and spousal abuse and generalized racism with a kind of humor (black though it may be) that feels a touch dishonest. The real raw brutal poverty of most of America is absent here. Harrelson’s family is too wholesome by half. The children are rather too smart, finally, and too well adjusted. The bleakness and hopelessness of small town America is airbrushed aside. In its place is something that is close to a post modern version of Frank Capra. Well, perhaps Capra meets Lubitsch meets Norman Rockwell. It is no surprise this is a well received film, critically. It flatters the well educated audience but it does so with at least relative sincerity. And partly there is the pleasure of a very good cast being directed to do less of everything than they normally do.

“But what I mean is that the visible stigmata marking the character moreand more over the last ten years or so only helped accentuate a congenital weakness. In more and more resembling his own death, it was his own portrait Bogart was completing. Doubtless the genius of this actor who knew how to make us love and admire in him the very image of our decomposition will never be sufficiently admired.”

Andre Bazi (On the Death of Bogart)

But my trouble with McDonagh, and I generally like and respect his work (again he knows how to write and there are countless tiny examples in the film, notably the notes Harrelson leaves behind) is the comedy part. For the humor masks something, and it serves to remove those things that are not funny. Ebbing, Missouri, and towns like it, are locations of misery and anger and violence. A violence, too, that comes from the system that has abandoned these places. There are no meth cook houses dotting the countryside, no noticeable homelessness, and that missing part of American rage and despair feels like an important omission. But McDonagh is, again, a very sure footed creator of audience friendly product. He offends nobody. And that is a problem. So as much as I think this film has countless virtues, it still never rises to the level of a Fassbinder or Bertulucci, or Pasolini. Compare Why Herr R. Ran Amok, a Fassbinder comedy from 1970; comedy of sorts anyway. The comparison demonstrates the ways in which McDonagh seduces the audience, an audience he knows well. And that is not, per se, a criticism. The uniformity of praise for McDonagh’s new film is, as I’ve said before, a red flag. But its also hard not to admire the writing — on a line by line basis — and the acting (back to that below).

Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri (Martin McDonagh, dr. 2017).

But there are a couple other recent films and TV shows worth mentioning here. One is the third season of Gommorah, the Italian crime show set in Naples, created by Roberto Saviano (based on his book). It is easy to dismiss this show as wantonly violent and another typical crime series about gangsters and drug dealers. But it is not typical at all. Firstly the police are mostly absent. And this is a film in which the neglect of the underclass is underscored in every frame. This is that part of society which neo Liberalism has just forgotten about. And these are people who are born in hopelessness. The gnawing ambition of the third season’s protagonist is to run the drug business on two streets in central Naples, the very streets his father was promised before being killed. The horizon for those born in acute poverty is adumbrated. One of the more successful capos says to a young aspiring accountant for the mob, “you think you can hide the stench of poverty by being polite”. The narratives meander for these are lives that meander, of necessity. The almost eerie landscape of Naples, mostly the poorer parts, is testament to the social neglect that colors the entire project. For even the grander homes of the bosses feel suffocating and stale. It is a relentless narrative of traumatized society as it exists in much of the EU today. And it is a series that gives a good deal of space to characters who think. Its remarkably introspective for a crime show. And there is no commentary on the bad haircuts and garish taste of this corner of the poor. The camera and the directors never assume a position of superiority. Over and over the story returns to the built-in repetitions of lives bereft of choice. Hence it has a kind of hypnotic quality. Fatalistic and nearly nihilistic, it is far truer to the state of vulnerability for many today than McDonagh’s film can reach.

Bringing Up Baby (Howard Hawks, dr. 1938).

But what of this question of performance? Francis McDormand is self consciously plain. Her sense of timing and phrasing is self consciously careful, but its certainly nothing that transforms recitation the way a Gielgud or Derek Jacobi transform — it is not that kind of craft (and an interesting comparison might be Frank Langella, with whom McDormand shares a certain superficial similarity in cadence and delivery. Langella is concerned with where his words land, and McDormand is not). Hers is not the narcissism of a Helen Mirrin, the now go to grand dame of Royalist narratives, or god forbid the caricature the once rather splendid Judi Dench has become. McDormand is not, as Bazin said of Bogart, someone in whom we see the eminence of our decay. Nor its dignity. McDormand though is still relying on the naturalistic moment, the step back from abject misery is avoided. Scenes become about McDormand even when they shouldn’t. She allows cranky but not damaged. Or rather we see an actress retreat, when perhaps that is too coy. There is not (again Bazin) the interiorizing of ambiguity. But here again this is a sort of comedy. McDonagh’s alibi in a sense. Its not tragedy. And its not. And the racist and none too bright Sam Rockwell cop acts as a reminder for the audience that, yes, this is comedic, this is exaggerated. And McDonagh gets away with it because he is genuinely funny. Witty and acidic and pitch perfect in those asides that remind me of a 40s screwball comedy. Cary Grant would work well with McDonagh. So would Irene Dunne (so maybe McDonagh is more a post modern Leo McCarey?) McDonagh is far better a writer than Aaron Sorkin. And partly this is that behind the wit there is a cynicism to McDonagh. Not the ironic snark of Sorkin, but a simply cynical sensibility (another actor who would fit is George Sanders, and perhaps my softness for McDonagh is that he feels like a throwback to Joe Mankiewicz). For McDonagh is not a great artist. But, at least in terms of this latest film, he is the antidote to the plague that are the Cohn Brothers. Still, this is bourgeois affirmative work.

There is also a discussion to be had, but a larger one than there is room for in this posting, on the social context for comedy. For comedy operates in a way more reflective of certain assumptions about the society in which it takes place. A Buster Keaton could not, probably, be viewed as funny in the same way, if he were making films today. But, of this I am far from sure.

Howard Hawks

“Hawks’s oeuvre is equally divided between comedies and dramas – a remarkable ambivalence. More remarkable still is his frequent fusing of the two elements so that each, rather than damaging the other, seems to underscore their reciprocal relation: the one sharpens the other. Comedy is never long absent from his most dramatic plots, and far from compromising the feeling of tragedy, it removes the comfort of fatalistic indulgence and keeps the events in a perilous kind of equilibrium, a stimulating uncertainty which only adds to the strength of the drama.”

Jacques Rivette (On the Genius of Howard Hawks)

Perhaps McDonagh is the contemporary Hawks, but the Hawks of Monkey Business and not The Big Sleep. But it is possible, I think, to see some of that later Hawks ambivalence; the uneasy quality of Hatari or Rio Lobo, or even El Dorado in much of Three Billboards. McDonagh’s last film, Seven Psychopaths, was a kind of parody of Hollywood ambition and politics. But it wasn’t The Player, it was weirder than that. For it was intentionally superficial. It was the fetishizing of a fetish. Rivette was right to see in Hawks a director who consistently shuddered at the inescapable infantilism of American society. For Hawks was the great moralist of American cinema. McDonagh is not, but he may well be doing something equally serious. For McDonagh is not himself seduced by the infantile. The society he depicts is seduced by the temptations of youth — as Rivette and other Cahiers writers saw — but McDonagh himself is looking to do something that places comedy in a state of ambivalence again. He is not the moralist, but only the stenographer of infantilism and trauma. He is aware of superficial, without making it something to stigmatize. In that sense, he is compassionate. He is making comedies of ambivalence, not in their humor and jokes but in that which is missing.

Accident (Joseph Losey, dr. 1967).

“This is perhaps the principal difference between the literary work and the cinematic work. The linguistic and grammatical domain of the filmmaker is constituted by images. Now images are always concrete (only by a foresight embracing millennia could one conceive image-symbols which would know an evolution similar to that of words or at least roots, originally concrete, which, with use, have become abstract.) This is why cinema is, today, an artistic and not philosophical language. It can be a parable, but never a directly conceptual expression.”

Pier Paolo Pasolini (The Cinema of Poetry)

Gertrude (Carl Theodore Dreyer, dr. 1964).

“But for the believer, applying the religious interpretation to the intrinsic meaning of these events presents no problems. The ambiguity itself is in a sense a criterion of authenticity. The illusory area of external visions and internal voices would be far more alarming. Here everything is so profoundly marked by corporeality and so far from fantasy that it presents no problems and there is no difficulty in recognizing the finger of God. ( ) In other words, the ambiguity is the mode of existence of the Mystery which is the safeguard of freedom.”

Amedee Ayfre (On Italian Neo Realism)

Another film out this holiday season is The Killing of a Sacred Deer, the third feature by Yorgos Lanthimos. While I liked Dogtooth, a sort of Ionesco absurdist black comedy, the new film — like McDonagh’s latest — is much more ambitious. Like McDonagh it is getting glowing reviews and comparisons to prime Polanski and to Michael Haneke. It feels more like a sort of gloss on Dryer, though, finally. But without the grandeur of Dreyer’s mise en scene, nor his philosophical depth. Part of the problem, as with Haneke (for me), is that the quality of the arbitrary becomes itself a bourgeois gesture and an annoyance. Dryer made films, in a sense, for himself. He was working out whatever strange idiosyncratic spiritual struggle he had assigned himself. But Dreyer was also deeply and acutely aware of the social forces behind his allegories. I am not sure Lanthimos is, and I think there is an unfortunate quality of Lynchian bourgeois affectation at work. With Dogtooth the comedy was black, but it operated AS comedy. And not even ambivalent comedy. And it succeeded. And it was darkly but relentlessly funny.

The Parson’s Widow (Carl Theodore Dreyer, dr. 1920 silent).

Walker Evans, photography.

“I propose that we treat the spectators like snakes that are being charmed.”

Artaud

Luc Moulett wrote, quite a few years ago…“Young American film directors have nothing at all to say, and Sam Fuller even less than the others.” But Moulett meant it as a compliment (as it was) and in one sense I think McDonagh might well be viewed this way. Whenever I am charmed by a film, I skunk around for days after interrogating myself and looking to understand my guilt. But I suspect the problem is just that nobody today is Antoniioni or Bresson or even Hitchcock or Hawks. Let alone Dreyer. And along with Sirk, Dreyer is the most difficult film artist to write about (maybe Jean Marie Straub, but then Straub is perhaps not even making films, really). And that is because the idea, firstly, of religious art is now anathema, and secondly, Dreyer is the anti-entertainer, and thirdly, and most importantly, Dreyer’s art is one of contemplation and the draining of superfluous experience. He is the Kierkegaard of cinema. The fact that one cannot absorb Dreyer easily, or often, is interesting. Festivals of Bresson …a feature every night for a week, is bearable. Try that with Dreyer, and the result is a kind of madness. This speaks to the genius of Dreyer and the fact that he may be the true purist of all cinema and maybe its greatest artist. For the fascinating aspect of Dreyer is that as his oeuvre grew, his cinematic taste distilled. In Gertrude (1964) there are no close ups, very little movement (scenes with actors just standing can last seven or eight minutes) and a stripped down decor. Psychological realism? Hardly. But it is more the landscape of interiority, of human interiority. And there is no decoration in the antechamber to our soul. And as inner life is further colonized today, Dreyer may be the aesthetic corrective. He and Rosellini.

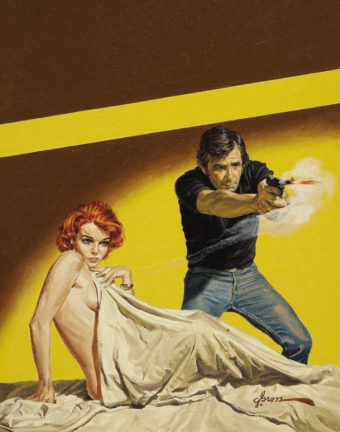

George Gross, pulp illustration. 1950s.

Acting for film is complex. Acting in theatres, that being-on-a-stage process of revealing is not what one does in front of a camera. And cinematic history is so entwined with celebrity and *movie stars* that is very hard to grasp the fluidities of a criteria for film performance. Francis McDormand reminds me on some bizarroo world level with Elizabeth Warren. It is the presentation of self, the unadorned faux truthiness that is meant to pass for integrity (this is just pure free association, mind you). John Hawkes, on the other hand, is an actor who reminds me of good actors from the 1950s. Ralph Meeker or the early nasty Fred McMurray. Or Dana Andrews. Stars, all of them, but also working class. Andrews was the the third child of thirteen born to a Mississippi Baptist minister. McMurray was born in Kankakee, Illinois, the son of a music teacher at high school and Meeker was born in Minneapolis to working class parents, and then joined the Navy. Nobody was a Mouseketeer. The point, I think anyway, is that the contributions of the working class to art in America were pronounced. That is no longer the case. The vision of prairies and rivers and barges and traveling Preachers and youths spent in the Merchant Marines (Kerouac, and Jack London, as well as Cisco Houston and Jack Lord…yes Jack Lord). But so also Oliver Stone and Gary Snyder. In a curious way this all seems pertinent. For the loss of that contribution, however illusive it might have been at times, is part of the conformism and reactionary neurosis of contemporary America. The internalized ambivalent — that is no longer the role of art and culture. Nothing is allowed to be ambivalent. The struggle of labor, the solidarity, however fragile it often was, is now replaced with a hideous form of narcissism that is feeding on its own psychic entrails. The ruling class has shaped a society, now, that cannot sustain its own mythology. At all. The endless ever more desperate militarist fantasy of American TV is actually embarrassing. Its hard to get angry, even as one recoils, because the Boss Tweeds of the system, for all the transference of capital to this upper 1%, is more unhappy than previous Capitalist overlords were — and maybe that is because they cannot even grasp notions of philanthropy … of giving without strings. America is the society of strings. Of fine print. Of loopholes.

Lola Montes (Max Ophuls, dr. 1955).

The ruling class is unhappy because the horizon of total global hegemony is now in view. It is likely impossible, even now, but they can see it. And they experience a slight hollowness in the pit of their stomach, a quiver of fear — for what do you get when you get everything? You get nothing.

I can recall the film clubs in NYC in the 70s. I’d go to two a night, often. People would argue over who had the superior tracking shots, Joseph H. Lewis or Minelli. The best sense of how to introduce a a female lead…Preminger or Jacques Tourneur. Was Ulmer overrated? I mean the topics and debates never ended. I was stunned when I taught at the Polish National Film School to find almost no students who even knew who Edgar Ulmer was, or recognized the names of Max Ophuls and Abe Polonsky. They did know the latest lenses and steady cam innovations, They knew which format was best for this or that effect. They simply did not view film as art. In fact *art* was not in their vocabulary. Today the Cahiers critics are largely dismissed. I’m not sure what is being read on film, Deleuze no doubt. There are great people writing on film (Jonathan Beller for one) but mostly even very sharp marxist critics write terribly when they try to tackle cinema. They write sort of morally indignant reviews, mostly. And clumsy ones at that. For again, the forgotten element is form. Nick Ray is great not because of the message of his scripts, but because he saw the world as cinema. The same, I think, could be said for Anthony Mann. And certainly, in a sense, for Max Ophuls. And Ophuls is superior to either ( Ray fans will argue) because of his intellect. Only Bill Wilder ever made movies as smart as those of Ophuls.

Carl Theodore Dreyer (photo by Richard Avedon).

In this context I might suggest a New Year’s viewing of Lola Montes, most certainly Ophuls greatest film (though I have a fondness for Caught, if only for James Mason). Ophuls struggled to get this film made (it was I believe an outlandishly expensive film for French producers of the time) and he died still in litigation over the final cut. Criterion has now restored the definitive directors cut. Made in 1955 it was Ophuls first color film and he was forced to use Martine Carol as the lead (the producers wanted a name). I actually think Carol is fine and is directed as a sort of mannequin around whom the world revolves. It is also a film that borrows from Kafka’s Amerika, and prefigures much of the second half of the century’s experimental theatre. In it one can see Beckett and Genet, as well as Ionesco, Sławomir Mrożek, and Durrenmatt. And maybe most of all Peter Weiss. But it is a film for contemporary discussion, too, because the central character of Lola, (the real life Lola was once called the most scandalous woman in the world), is examined by Ophuls through the lens of a cheap American circus (with the extraordinary Peter Ustinov as ringmaster) as questions of female beauty, ageing, and career loom just outside the frame.

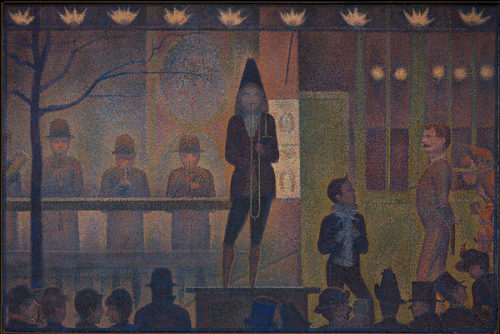

Georges Seurat (1859– Paris)

“The circus is a celebration and mockery of Lola and her life that adds an interpretive gloss to the flashback sequences. By addressing us directly as an audience, these scenes confront us with our own lurid fascination in Lola’s exploits and, indeed, Lola’s body. This makes the movie’s wonderful, sad final shot all the more pointed, because even as Ophuls makes explicit Lola’s tragic fate, he indicts us for our complicity in craving the spectacle she represents. Ravishing and reflexive, sumptuous and sad, Lola Montes has finally received treatment worthy of its place in film history. Ophuls died just two years after the movie’s release, and it breaks my heart to think that he never saw such a magnificent restoration as this. But as someone who loves the cinema, I count myself very lucky to have had the opportunity to see it myself.”

Chris Wisniewski

It is also a movie about making movies. For it is shot on a sound stage which Ophuls makes no attempt to hide. So, as comparisons go, one might look at the the insipid juvenilia of Birdman, say, or pick any one of the Cohn Brothers (Hail Caesar maybe)… (or half of Danny Boyle’s films). But Ophuls is not telling Montes’s story as allegory, really, nor is she ever a symbol or metaphor. For Ophuls, like Sirk, is coming as close as one can in cinema to creating a kind of thought — a knowledge. If Shakespeare did it (most acutely in the Mad Tom scene in Lear) and later the great modernists of the absurd (Genet and Pinter and Beckett and et al) saw in that single scene the essence of theatre form, the mechanism required the presence of both actor and spectator. It required, even more significantly, the empty stage. A stage. And that was and still is impossible in cinema.

Red Desert (Michelangelo Antonioni, dr. 1964)

But Ophuls and Sirk were examining something of how the recorded performance can avoid psychological realism and a representational strategy for cinematic narrative. If they could not have a *stage*, they could film where the stage formally was (to paraphrase Sheldon Leonard). As Herbert Blau put it, all theatres have the memory of the curtain that raises at the start of a play — even if it has long ago been removed. It is possible to include Mizoguchi in the above group, too, and probably Bresson and Antonioni. But the point is really that for such a young art form, cinema is already erasing its history. I think a note here is required on Andrew Sarris. For Sarris was the great English language voice for French auteur theory. And even if he got rather muddle headed by the end, Sarris deserves a good deal of credit.

“If Sarris became the critic I read and reread more than any other, it was perhaps for the sense that at the centre of his writing was a reverence for film history – his kind of film history – as a secret poem of light, whose variations were infinite and whose traces might be found in the most unexpected places.”

Geoffrey O’Brien

All That Heaven Allows (Douglas Sirk, dr. 1955).

I think given this amnesia on cinema history (an amnesia that is operates on social and political levels, too, obviously) the ideas of what performance is and how it works and doesn’t is a difficult topic. The critical vocabulary for culture is itself compromised. Performance is that which everyone lives today in the societies of surveillance. The new fascism of the West, more opaque than any before it, more user friendly, and more generalized in its presentation, has meant that a performance such as that of Obama is viewed through a lens that has as its guiding principle the most diluted form of consensus imaginable — performance is life, now, and the academia is complicit in inscribing a pretend populism that rejects critical questioning. It embraces any standard received wisdom as probably correct. Given that, film as an art form…the most consumed art form in the world today… is hard to discuss because people so profoundly identify with their personal *likes* . What such preferences are based on is usually unclear, but that hardly matters.

Thank you Mr. Stepping for yet another film history lesson and critique of modern art, society, and our ever-shrinking choices in regard to vital content.

I am dying of thirst and drowning in mediocrities’ pool of film choice that is available. The art house seems all but dead, gone the way of critical thinking and replaced by censorship sponsored propaganda as film.

I am going to be lazy and ask you where and how to source any and all of the films you mentioned in this article. Hurts to be in the US these days.