Gerhard Richter

“But to the degree that this left seeks to change the world without taking power, so an increasingly consolidated plutocratic capitalist class remains unchallenged in its ability to dominate the world without constraint. This new ruling class is aided by a security and surveillance state that is by no means loath to use its police powers to quell all forms of dissent in the name of anti-terrorism.”

David Harvey

“A painting can help us to think something that goes beyond this senseless existence. That’s something art can do.”

Gerhard Richter

“…that people on the Left find increasingly that they have lost faith in the traditional diagnosis or in some part of the traditional recommended therapy. Either the malaise is not located in the economic structure, but is even more deep-seated, such as in the structure of rationality itself, or the form of political action traditionally recommended by those on the left is likely to be ineffective or even counterproductive.”

Raymond Geuss

I have been thinking about Gerhard Richter this week. I don’t know why, exactly, except that I read something mentioning his age (85 now I believe) and thought, well, he won’t be around, probably, too much longer. And why should that matter? I guess because Richter has always had an effect on me. And because he is widely regarded as the greatest living painter. An absurd designation but still one that is interesting in this particular case. His work sells for insane amounts today (20 some million pounds as of 2012, which was the last time I noticed). And that for one of his slightly cynical *squeegee* paintings (perfectly sized for hanging on the wall of expensive penthouses or in luxury yachts). I say slightly cynical because these works are still very good, I think. And of course one will have to discuss what *good* means, as always, in art works.

Tilo Baumgantel

Richter studied at the Dresden Art Academy, in what was East Germany. In 1961 he moved to Berlin, in the West. But his fundamental sensibility, artistically, and perhaps technically, was based on the communist principles he learned at the Dresden Academy. He was just outside the city, as a boy, when the Allies fire bombed Dresden. The Nazis euthenized his mentally unstable Aunt, and several other family members died in the war. Richter is often compared to Anselm Kiefer, and I think this is logical, though I’m not sure the usual comparisons are the right ones. Both Richter and Kiefer are painting about death. They are also, always, painting about memory, and about history — especially German history. But the photorealist works of Richter have always struck me as among his most effective. For they are not pop works, but they employ the grammar of pop and advertising. The well known October series, based on the Baader-Meinhoff Group, and more specifically, their death in custody, are paintings, but based on photographs. And some are really just altered photos. They are ‘momento mori’ works. Now, I am not writing a post on Richter per se. But more on the relationship of art to Capital, and to mass culture, and to something maybe more elusive. And that has to do with interpretation and meaning. With Richter, I think that early training in Soviet realism was seminal. And looking at both the East German painters of the Leipzig Academy, and the Romanian painters active today who came out of the University of Art and Design in Cluj-Napoca is revealing. These schools were mostly shut off from Western influences. As Arno Rink (director at Leipzig) put it; they were protected from the influence of Josepth Beuys.

The Leipzig phenomenon was in good part the work of canny gallery owner Gerd Harry Lybke, who began as an agent for Neo Rausch. But Lybke is right when he says that subconsciously the art world — whoever that might be — were longing for something and these painters delivered. Both these movements exhibited something critical of bourgeois respectability. And this serves as an awkward segue to questions about how contemporary painting, and art in general (perhaps) are experienced today.

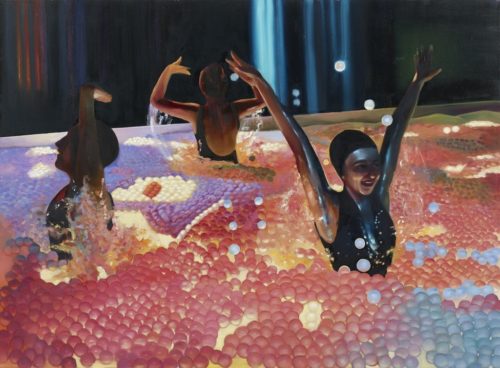

Sergiu Toma

“‘Bourgeois’ first appeared in eleventh-century French, as burgeis, to indicate those residents of medieval towns {bourgs) who enjoyed the legal right of being ‘free and exempt from feudal jurisdiction’ (Robert). The juridical sense o f the term— from which arose the typically bourgeois idea of liberty as ‘freedom from’— was then joined, near the end of the seventeenth century, by an economic meaning that referred, with the familiar string of negations, to ‘someone who belonged neither to the clergy nor to the nobility, did not work with his hands, and possessed independent means’. “

Franco Moretti

In England, especially if one looks at the big industrial cities (Manchester, or Birmingham et al) one saw (as pointed out in the Communist Manifesto) a lack of middle rank. There were rich industrialists, the owners, and there were the poor, the workers and the very poor who had no job. The choice of the term *middle class*, as opposed to bourgeoisie, was (per Moretti) a choice that was taken from a position of superiority. The ruling class preferred middle class as a way to normalize a political containment.

“Then, once the baptism had occurred, and the new term had solidified, all sorts of consequences (and reversals) followed: though ‘middle class’ and ‘bourgeois’ indicated exactly the same social reality, for instance, they created around it very different associations: once placed ‘in the middle’, the bourgeoisie could appear as a group that was itself partly subaltern, and couldn’t really be held responsible for the way of the world. And then, ‘low’, ‘middle’ and ‘upper’ formed a continuum where mobility was much easier to imagine than among incommensurable categories— ‘classes’— like peasantry, proletariat, bourgeoisie, or nobility. And so, in the long run, the symbolic horizon created by ‘middle class’ worked extremely well for the English (and American) bourgeoisie: the initial defeat o f 1832, which had made an ‘independent bourgeois representation’ impossible, later shielded it from direct criticism, promoting a euphemistic version of social hierarchy.”

Franco Moretti

Gerhard Richter ( The October 18, 1977 series, photo paintings).

One of Moretti’s keenest insights is that regularity and not disruption were the hallmarks of bourgeois cultural production over the course of the 19th century. He is speaking here primarily of the novel, but it is true of all the arts. And the received wisdom of bourgeois unpredictability was actually illusory — and hence the rhetorical emphasis on innovation which was mostly non-existent, especially in terms of style. The ruling class, in a sense, kept doubling down on the idea of change and capitalist dynamism. This was to change, some anyway, at the end of the century and the beginnings of the 20th century. At least in certain countries of Europe (Germany in particular). But this belief and valorizing of invention has carried over to U.S. cultural output, where there has been an insistent selling of the idea of the *new*. And by mid century the *new* was to be increasingly associated with youth.

The entrenchment of Capitalism, of course, was narrated as a *dynamic* system of free enterprise and self motivation — but in narrative the bourgeois hero was simply not, well, heroic. That mitteleuropean bookkeeper and clerk was the subject of much early 20th century writing, including Kafka. The bourgeoisie invented no mythology for itself, as had the aristocracy. No noble Knights or valiant adventurers. Only the keepers of ledgers and finance. And this is a fascinating topic, really, if one looks at the culture of advanced capitalism. Moretti posits that where capitalism is most solidifed, narrative and stylistic mechanisms replace character. Or become character.

Ana Maria Micu

Hannah Arendt suggested the bourgeoisie in history to achieve economic pre-eminence without a desire to rule. I’m not sure that’s exactly true (the desire for political rule) but effectively it turned out that way. Perry Anderson added that after the second World War, there was a belief in democratic self determination, which in turn was driven by, and created by, the belief that there was no ruling class. This signaled the end of, officially, bourgeois culture (Thomas Mann)… and it coincided with the elevation of commodity culture and the hyper reification of advanced capital.

“…the great technological advances of the nineteenth and late twentieth century: instead of encouraging a rationalistic mentality, the industrial and then the digital ‘revolutions’ have produced a mix of scientific illiteracy and religious superstition— these, too, worse now than then— that defy belief. In this, the United States of today radicalizes the central thesis of the Victorian chapter: the defeat of Weberian Entzauberung at the core of the capitalist system, and its replacement by a sentimental re-enchantment of social relations.”

Franco Moretti

Christian Postcard, U.S. date unknown.

There is no way to over-emphasize the role of sentimentality in American culture. No way. It literally saturates everything from pop culture to prestige art forms and it even has shaped language and vision. Painting has, since WW2, become ever more sentimental. And it is that, possibly, that accounts for the distinct qualities of Romanian and East German painting. And to a degree for the facile technique of Richter. For Richter was acutely aware of Western commercialization. He early turn to Pop was short lived, but he never lost the awareness of how morbid and stultifying was Western capitalism. But sentimentality occurs in what passes for today’s avant garde, in rather stealth fashion. It is the self conscious art of *outrage* that actually is masking a core sentimentality. Works intended to shock often, if not usually, are actually intended to legitimize the respectability they attack. Stuff such as Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ, as an example (if not a cliched one) are really about the public outrage and then the re-knitting of social cohesion around the *official tolerance* that comes from acceptance. But that is, really, too simplistic. There is a more complex dynamic at work in *shock art*. But also, before getting further into that and its relationship to the sentimental, it is worth noting the linkage between this closeted sentimentalism and the growing conservatism of leftists in the West, at least in terms of a paranoia about conspiracy theories and the like.

Wolfgang Mattheuer

I saw someone write, on social media, in regard to a story about Chris Hedges (critical of Hedges and considering his possible CIA affiliation) that “we wonder why the left is not taken seriously”. Now, never mind what one thinks of Hedges, the germane element here is that sentence and its implications. The question is *who* is not taking the *left* seriously? What does that even mean? I suspect only a college educated white man (maybe some white women) would write that. Its the grammar of fraternity houses and dorms. Its the desire to fit in, to avoid ridicule. Hence the great appeal of stigmatizing those you fear with labels like *conspiracy theorist*. There are other labels that parallel that (genocide denier is one). It is not about facts, not about argument. Its about labels and the nature of social relations that have been tainted by what Moretti called sentimental re-enchantment. Illana Simmons described the sentimental as that which ‘bullies you into certain feelings’. And I think that is a good capsule description. And this subtle Puritan bullying occurs through the various levels of and in social relations. Milan Kundera wrote… “We cry one tear for the children playing on the grass, and then we cry another tear for our ability to cry at the children playing on the grass!” In other words sentimentality is comfortable in narcissistic culture or with narcissists. But there is guilt, too. And national differences, I think. French sentimentalism is not the same as American sentimentalism. The French condescend to their emotions, often with bemused humor. Americans, as Puritans, cannot do that. For educated Americans there is an additional taste anxiety. Not trusting their own responses seems very American to me. And it is partly a dim awareness that, in fact, their education IS lacking, but its also that the enjoyment of popular or mass culture leaves one anxious all by itself.

Donatello (15th century).

“Sentimentality will be defined as an emotional disposition that idealizes its object for the sake of emotional gratification and that is inherently corrupt because it is grounded in epistemic and moral error. “

Nada Gatalo

Now Norman Rockwell is sentimental. But then so is Fragonard. Some consider Raphael sentimental, an opinion I’d not argue with. Not when you compare Raphael with, say, Donatello or Bernini, or Goya. I wrote before of Donatello’s extraordinary sculpture of the prophet Habakkuk http://john-steppling.com/2015/10/what-is-impossible-to-remember/

This remains a very favorite artwork of mine. One cannot exhaust the complexities of viewing it. Now this re-enchantment should be clarified, I think. For this is, in a different usage of the term, a disenchanted society. But this is semantics. The contemporary enchantment, or disenchantment, is linked to corporate anonymity, to the reductive narrowness of emotion permitted to the populace. Condemnation is so much easier than compliment, unless of course the compliment or approval is already approved. And this is perhaps the lesson of bourgeois culture under advanced capital.

Pippo Rizzo

There was a Tate exhibition in 2012 on Victorian Sentimentality. It was the most popular and well attended exhibit that year (or maybe since). The reviews all praised the works and suggested a re-evaluation of sentimentality. And this is part of the current vogue regarding Victorian culture. And there was been a reintroduction of sentimental themes and style in artists such as John Currin, Kara Walker, David Humphrey, and Faith Ringgold. And Rockwell himself has undergone a rehabilitation with several different touring exhibitions. There is a clear connection, too, between the sentimental and authority and the status quo. Sentimental images are predicated upon unchanging universal values. They are inherently conservative. And once there was a ruling class irony in the approach to kistch and sentimental work, today that irony is mediated to a large extent. The rehabilitation of sentimental grammar and style is treated as genuine and an expression of trust in the system. It is the exceptionalist sentimental.

In the introduction to the First Post-Impressionist Exhibition in England, Cezanne said that his aim ‘was not to paint attractive pictures but to work out his salvation’. The ascension of bourgeois art to a place of some importance accelerated, I think, toward the end of the 19th century. But whenever the greatest changes occurred, the elements or forces at work toward the beginning of the 20th century coincided with several things. And psychoanalysis was one of them, and of course Freud himself was a kind of symptom of the time, too. I only mention this here because there is something in this relationship of creativity with anxiety and even with depression, that has not really left Western culture. But it has, to be sure, changed. Moretti mentions Dostoyevsky toward the end of his book The Bourgeoise, and how for most Russian artists, there was a tension with the concept of *byt*…which Jakobson said was untranslatable. It means a kind of everyday-ness. And that it was this ‘fortress’ of predictability and banality that Dostoyevsky challenged in his narratives.

Jean Honore Fragonard

“Dostoevsky’s poetics requires ‘the creationof extra ordinary situations for the provoking and testing of a philosophical idea’, adds Bakhtin: ‘points of crisis, turning points and catastrophes [when] everything is unexpected, out of place, incompatible and impermissible if judged by life’s ordinary,“normal” course’.”

Franco Moretti

And it is exactly this tension that Americans cannot understand. The Calvinist Protestant or Puritan ethic of work, and the denial of pleasure, operate in a world view that has does not include a backdrop of numbed everyday-ness. For nothing is ever everyday, everything is always special and new. Exceptional. In a recent episode of The Brave, a jingoistic TV drama about the military, the special operations unit that is featured in the show is assigned an assassination. They are to kill a terrorist (of course) who is Iranian (of course). Now, the presentation of this plot is laid out in just one speech, at the start, by Anne Heche (I know I know) and her bottom lip actually quivers. The intent is to signify clear moral seriousness. But the absurdity of the entire show is only revealed the more. Never mind that Heche lacks gravitas, the dialogue actually includes a list, a litmus test meant to make clear that killing is OK, but only under these special circumstances. I won’t belabor this, but only to point out that there is an absence of anything exceptional. There is no actual backdrop here, no world in which such cartoon soldiers operate. And this can be traced, in one respect anyway, back to this Calvinist purification of labor …of work. Work that may well be exploitative.

Oana Farcas

American TV and film suffer today from the banality of their repetitions at newness, at innovation, and so when looking to present, within a narrative, a uniquely grave event, it simply cannot happen. The over determined fixation on corpses and forensics suggest something related to this as well. The human interior; when it is psychically empty perhaps then shifts the exploration to a materialist bent. I don’t know, honestly. But there is something today that suggests that Utopian social projects are affected by the same forces that entrench the reactionary Capitalist system of domination. Raymond Guess has written a lot about Adorno. And his essay The Loss of Meaning on the Left, which is included in his most recent book (A World Without Why, 2014) touches on the ways in which instrumental reason erodes the ability to organize and work collectively. I have recently had some very strange and unpleasant arguments with people who self identify as leftists. I have no idea how any of these people would define the term *left*. But this is where, I think, Adorno, and really the entire Frankfurt School, are so important.

“In a society in which work and collective social life was sufficiently satisfying, one might think, the very question of the “meaning of life” would not arise. The very fact that this question does arise for a particular person in a particular society is a sign that that question for that person (in that society) has no answer. “The meaning of life” ought not to be reified. “

Raymond Guess

Hans Hartung

For the Frankfurt School the only real criticism they leveled at Marx was that he was too optimistic. That even the removal of private ownership of property and production would not necessarily change certain problematic aspects of human rationality. I am grossly simplifying here, but the question in terms of culture, and that means contemporary Western culture, for the sake of this posting, the damage of Capital’s durability cannot be dismissed. I see this in particular with a kind of narcissistic character armoring that (per Reich) feels entwined with the later history of advanced capitalism. In other words there is such a profound system of psychic oppression operating, and one that has operated in its acute hyper alienated manner now for at least fifty years, that the very language we use, the way we perceive the world around, the quality of our mental make up, is perhaps damaged beyond immediate repair. As Guess describes it, “Everything in contemporary society is part of an incipient single closed system of capitalist rationality.” And a coercive logic of conformism is operating constantly in almost every detail of our daily lives. Lives that are constantly being marketed to us as special and unique. The counter revolution launched against the Soviet Union and Communist China was partly just unconscious — the hegemony of capitalist rationality, of instrumental thinking, infected the entire planet.

Allow me a longer quote from Guess.

“Human “meaning,” at any rate, is not “verfügbar,” not producible, reproducible, or accessible at will, but is connected with and embedded in historically specific forms of human experience that are structured by unique human memories and anticipations.17 You cannot simply conjure real human meaning into existence by wishing it or through any form of simple manipulation. This aspect gets lost both because the objects we encounter become more and more the same and because we are increasingly trained to experience them only in a schematic way that does not go beyond subsuming them under crude general categories. In thus simply subsuming objects under pregiven schemata, I am acting not as the unique individual I am but as any-interchangeable representative-of-a-human-subject-whatever. In this way a kind of meaning—or perhaps Adorno might call it “pseudo-meaning”—is created and maintained as the artefact, finally, of a subjectless system of economic development, but it is not an appropriately human form of meaning.”

Alec Soth, photography.

The disorienting experience of talking to people who one assumes are not the enemy — and they are not, but they are so damaged and psychologically deformed that the sense of collectivity is very hard to sustain. It may well be that the road to the collective now runs through something like acute solitude. Some form of almost monasterial distance from this global machinery of pseudo society. The re-enchantment (or disenchantment if you prefer…because I suspect they are nearly identical) is one of holograms, of phantasms, illusion, and ghosts. And it is why I remain convinced that the transcendent qualities of art are of ever more cardinal importance. For the dynamic in creation of art is one that both encapsulates and negates the homogeneity of this daily system of illusion. Art then has to do something that offers a resistance, even if just psychically, to the subordination of emotion and thought to simple exchange value, to those pressures to extract profit.

“This is why the experience of the encounter and, I would add, of any encounter confronts psychical activity with an excess of information that it will ignore until that excess forces it to recognize that what falls outside the representation proper to the system returns to the psyche in the form of a denial concerning its representation of its relation to the world. An example of this denial is provided by the experience that the infant’s psyche may have at the moment when it is hallucinating the presence of the breast, and is therefore forging for itself a representation of the mouth-breast junction and may, suddenly, experience a state of privation. But what is true for this initial phase of psychical activity remains true for all its experiences.”

Piera Aulagnier (The Violence of Interpretation)

Walter Darby Bannard

“While public education has done much to meet capital’s demand for ideological conformity combined with the production of skill sets appropriate to the state of the division of labour, it has not eradicated the underlying conflict. And this is so in part because state interests also enter in to attempt to forge a sense of cross-class national identity and solidarity that is at war with capital’s penchant for some form of rootless cosmopolitan individualism, to be emulated by both capitalist and worker alike. ”

David Harvey

The role of art, for Adorno, but in another sense for most of the Frankfurt thinkers, is in negotiating the interstices between the spectacle, the projected image the system is constantly repeating, and the reality. Only, of course the reality is always going to be mediated by how deeply the accumulative wounds to the psyche metastasize. At the end of Moretti’s study he makes a distinction between the bourgeoisie before industrialization and then after. The prose of pre Industrialism is eclipsed by the *creative destroyer*, the poetry of capitalist development. And it was Ibsen who straddled this transformation. When the Frankfurt School thinkers are accused of nihilism, it is because they articulate that witnessing of this transition into bourgeois domination — at least in one sense. The crises of capitalism is also the crises of rationality, and of the belief in western individuality.

Holy Land Theme Park (closed, 1984). Waterbury Conneticut.

A materialist economic diagnosis remains valid. But this is a validity that feels fragile, psychologically, if not also in real terms. When Guess writes of the loss of meaning he is looking to something that remains opaque.

“…people on the Left find increasingly that they have lost faith in the traditional diagnosis or in some part of the traditional recommended therapy. Either the malaise is not located in the economic structure, but is even more deep-seated, such as in the structure of rationality itself, or the form of political action traditionally recommended by those on the left is likely to be ineffective or even counterproductive.”

Raymond Guess

Terry Eagleton noted the deep anxiety of the capitalist class, the ownership class.

“While ‘‘peripheral’’ countries were subject to sweated labour, privatized facilities, slashed welfare and surreally inequitable terms of trade, the bestubbled executives of the metropolitan nations tore off their ties, threw open their shirt necks and fretted about their employees’ spiritual well-being. None of this happened because the capitalist system was in blithe, buoyant mood. On the contrary, its newly pugnacious posture, like most forms of aggression, sprang from deep anxiety. If the system became manic, it was because it was latently depressed.”

František Kupka

Following on this was Thatcher and Reagan, and a rise in ever more naked policing of the populace. There was a general proletarianizing of the workforce. White collar workers, greater in number than ever before, also functioned in ways that felt more blue collar, at least to the extent they worked longer, had less protection, less security. The anxiety of both the ruling class and the working class, what served as the bourgeoisie, became ever more palpable. Alongside this, it seems to me, in an age of mass marketing and electronic communication, was a precipitous rise in a new form of narcissism. Anxiety and narcissism, and a generalized autism. All against one layer of backdrop which was more state repression. In the U.S. today the white Christian population is now dominant in areas where before they were only one part of this rural landscape. So, there is another aspect which might be described as mass regression. So, Marx was right, almost preternaturally so. As Eagleton notes (and others, like Tristram Hunt, who he quotes) the slums of Dhaka and Sao Paulo reproduce conditions eerily similar to 1840s Glasgow or Manchester. Capitalism was already threadbare in Marx’s time.

The role of culture, then, is layered with the new complexities of global Capital, in its ever more predatory state. The U.S. military, the organ of pacification for the Western ruling class, is in the hands of deeply damaged men. Maybe as never before. For all the blood soaked sadism of a John Foster Dulles, let alone the barbarism of a King Leopold, those in power and those funding them today are even more sadistic and certainly more deranged. In that sense the Trump administration is like some form of end-game for Capital.

Joel Meyerowitz, photography.

Which brings me back to art, since that is what I know best, or think I know best. What seems evident looking at the history of Communist countries is that however dysfunctional they may have ended up, they were not predicated on intentionally ‘creating’ suffering. That is the difference and even writers like Eagleton seem to not realize this. But one of the failures of much leftist policy is seen in the suspicion often displayed toward art and culture. In the West, it is common to hear people off handedly dismiss art, and then point to the insanity of Southeby’s auctions or the price fetched by various not very significant artworks. But that is a philistine position. And it also feels related, somehow, to the distrust of Freud. That Rothko sells for millions does not, finally, negate the work of Rothko. Gerhard Richter retains something profoundly unsettling, and genuinely disruptive, even while being crowned the greatest living painter. There is great work being made. Some is validated by galleries and critics, and some is not. Some is invisible. But to somehow become cynical about culture is one of the great triumphs of ruling class manipulation. Richter has written about seeing Pollock for the first time. The singular feeling he was gripped with. I remember going to the Modern in NYC as a teenager, really, and feeling I had discovered in those Abstract Exrpressionists another chapter in a hidden history of the society I was born into. Early blues music was another chapter, and Hank Williams yet another. And so was Anton Webern and Stockhausen. And then I remember those at Black Mountain College, and then the Bauhaus. But saying such stuff leaves one open to ridicule. Cynicism is much like sentimentality and irony. Its an infection.

Francis Bacon (1946).

“My hypothesis concerning the primal, as creation repeating itself indefinitely throughout existence, implies an enigmatic interaction between what I call the ‘representative background’ against which every subject functions and an organic activity, whose effects we can perceive, in the psychical field, only at special, privileged moments, or, and here, too, in a disguised form, in psychotic experience. Having defined the term ‘borrowing’, we can now turn to the analysis of the represented: that is to say, what we suppose that a hypothetical, impossible look would see if it could observe the pictographic representation.To speak of a hypothetical, impossible look is enough to recall that we only reconstruct what seems probable to us, on the basis of knowledge that the analyst may have of the experiences of subjects who have long since gone beyond the moment when only the primal process occupied the stage.”

Piera Aulagnier (The Violence of Interpretation)

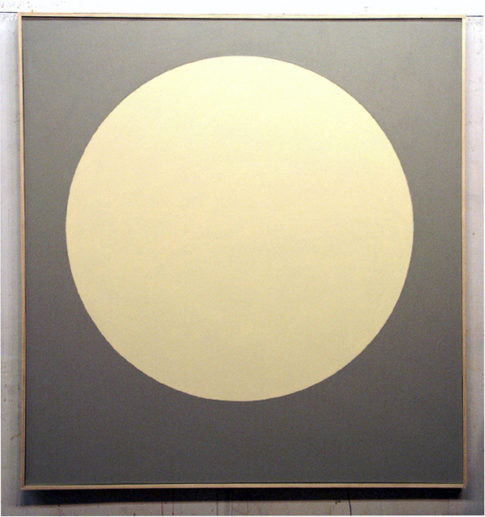

Agnes Martin

Art operates in hugely overdetermined ways, both in how it is experienced, and in how it is made. Auglanier is among the more unique writers on psychoanalysis, and one I have a great affinity for. Perhaps it is because the density of her writing is never meant to be easily grasped. Maybe its hardly even meant to be grasped. But that in no way, it seems to me, lessons her truth. For this is the deep and mysterious arena of our private damage and madness. To think you are not mad is the greatest form of madness today. The therapeutic culture which affluent white liberals seem so steeped in is really the short hand that serves to ward off those terrors that strike one out of the blue while walking down the street. They pass, usually, and often in a heartbeat. But they leave traces and perhaps it is in those traces that artists like Agnes Martin, or Pollock, or Richter even, transcribe something. It is for us to decipher these signs. As Auglagnier suggests, this is at the most primal level, and is never far from the psychotic. But that is where we live, all of us.

The road to the collective now runs through acute solitude: monasterial distance from this global machinery of pseudo society.

Yes, when all forms of engagement are in fact tar babies, to step back makes the most sense.

Is it a road to the collective as a utopia or a more abstract ideal?

Although I’m with you on the definitions and oppressive social function of sentimentality, I do not personally see the sentimentality in an artist like Agnes Martin or Pollack or Rothko(well, maybe) or Warhol. Not understanding what paintings you are thinking of as sentimental. Seems like you are connecting it with kitsch or irony? Please go into more detail…

I specifically said Martin Pollock and Rothko…and richter…were NOT sentimental. I posted a list of current sentimentalists…..john currin et al. Martin is the antidote to sentimentality.

“The bourgeoisie invented no mythology for itself, as had the aristocracy. No noble Knights or valiant adventurers. Only the keepers of ledgers and finance”

This explains whiteness in America….this is why the new era of white reactionary is so obsessed with imagery and cultural signifiers.