Cristina Iglesias

“It was the renegade French writer

Georges Bataille who noted that the major

difference between nature and human society

(especially late-capitalist society) was that

the former didn’t include the element of

accumulation. Nature is based on growth and

entropy, proliferation, but also on dissolution

and decay. If death didn’t exist, the nightmare of

permanent (and increasingly unequal) material

accumulation would never end.”

Ken Worpole

“Crematoria may be considered cultural places of death and remembrance where cultural

meanings are (re)produced and communicated through architecture, interior design and

landscaping. These influence emotions, either intensifying feelings of awe or anxiety or

assuage them.”

Mirjam Klaassens

“From this it happens that on earth the human race burns white bones for the Immortals on alters exuding the perfume of incense.”

Hesiod

Angelika Krinzinger

In 2010, an essay on and titled “Metamodernism” came out in the Journal of Aesthetics & Culture. It was an essay that for a variety of reasons (which I will try to elaborate upon) gained a certain traction and was disseminated and quoted pretty widely. It is borderline self parody, but then, that is perhaps even the point (no, really!).

“CEOs and politicians, architects, and artists alike are formulating anew a narrative of longing structured by and conditioned on a belief (“yes we can”, “change we can believe in”) that was long repressed, for a possibility (a “better” future) that was long forgotten. Indeed, if, simplistically put, the modern outlook vis-à-vis idealism and ideals could be characterized as fanatic and/or naive, and the postmodern mindset as apathetic and/or skeptic, the current generation’s attitude—for it is, and very much so, an attitude tied to a generation—can be conceived of as a kind of informed naivety, a pragmatic idealism.

We would like to make it absolutely clear that this new shape, meaning, and direction do not directly stem from some kind of post-9/11 sentiment. Terrorism neither infused doubt about the supposed superiority of neoliberalism, nor did it inspire reflection about the basic assumptions of Western economics, politics, and culture—quite the contrary. The conservative reflex of the “war on terror” might even be taken to symbolize a reaffirmation of postmodern values. The threefold “threat” of the credit crunch, a collapsed center, and climate change has the opposite effect, as it infuses doubt, inspires reflection, and incites a move forward out of the postmodern and into the metamodern.”

Timotheus Vermeulen & Robin van den Akker

Mira Dancy

This is what happens when there is no class based analysis — just for openers. The fact that in film the three directors cited later in the essay are Wes Anderson, David Lynch, and Michael Gondry speaks to both the infantilizing of culture and the depoliticizing of it.

“When Andre Leroi-Gourhan tabulates the efficiency of Zulu

swords and arrows in terms of the most up-ta-date knowledge of

weaponry, he is doing work that is obviously different from that of

the swordsmith of Bechuanaland who created the form of the

sword. The swordsmith’s choice of form was unconscious and

spontaneous; although it can now be justified by numerical calculations,

such calculations had no place whatever in the technical

operation he performed. But reason did, inevitably, enter into the

process because man spontaneously imitates nature in his activities.

Accomplishments that merely copy nature, however, have no

future (for instance, the imitation of birds’ wings from Icarus to

Ader). Reason makes it possible to produce objects in terms of

certain features, certain abstract requirements; and this in tum

leads, not to the imitation of nature, but to the ways of technique.”

Jacques Ellul

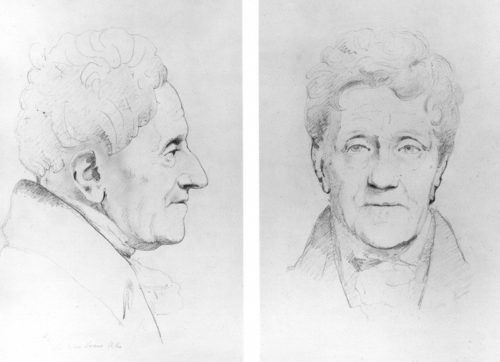

Lotte Jacobi, photography.

The depoliticizing of culture, in the West, and I’m thinking primarily Europe and North America — and perhaps only parts of Europe — is evident in not only in the banality of so much sanctioned art and cultural work, but also in the habits of mind one finds in cultural workers. I find very few artists in mainstream culture who have a vocabulary sufficient to discuss their work, or the work of others. I remember many years ago how great writers and poets would write essays on other writers. And painters and playwrights and even filmmakers who found something important in public dialogues about not just their own work, but the work of contemporaries and often of earlier artists. Off the top of my head I can think of Auden’s essays, and Pound, and Eliot, Olson, and Empson of course, and later the writings of Francis Bacon on painting. Poets routinely discussed poetry; Bly and James Wright, or Lorca and Neruda. Godard and the Cahiers critics, most of whom were directors, or were to become directors, produced an enormous body of critical work. From Artaud to Herbert Blau, Joe Chaiken, and Peter Brook, theatre artists wrote extraordinary critical works. The last great critical book of film theory I can think of was Paul Schrader’s book on Ozu, Bresson, and Dryer. Even in informal interviews directors such as Fassbinder and Antonioni spoke with clarity and with precision about their art. I’m not a fan of Updike’s prose, but I admire a great deal his critical writing on art. Is there another fiction writer since Updike who writes with that authority?

Kiev Crematorium, Baikov Cemetary. (Avraham Miletsky, arch.) Ludovico Lombardo, Photog.

“But the loss of creative power has disastrous psychological

consequences. ‘ When the human being is no longer responSible for

his work and no longer figures in it, he feels spiritually outraged.

The technical organization of the technical society may obviate

certain tendencies to aggression and frustration ( in a non-Freudian

sense ). But the annihilation of work and its compensation with

leisure resolves the conficts by referring them to a subhuman

plane. “

Jacques Ellul

Perhaps only architects write with any cogency about their practice. I happened to stumble on an issue of some architectural magazine that was devoted to crematoriums. I have always been fascinated with such structures– and it is worth noting that the first Crematorium in Europe wasnt built until the 19th century (in Italy). Of course Buddhist cultures have long had variations on what the West would call a Crematorium. And I wanted to juxtapose for a moment the failed collaboration between Peter Zumthor (a star-ahitect of sorts but usually a rather interesting one) and artist Louise Bourgeois. Together they built a memorial for the victims of witch trials in Norway (north Norway at that) in 1621. First off, one does sort of wonder at the urgency involved building a memorial to a 17th century witch trial from an era of almost continuous witch burnings in northern Europe, but never mind …the bigger question is why is it so bad.http://www.archdaily.com/213222/steilneset-memorial-peter-zumthor-and-louise-bourgeois-photographed-by-andrew-meredith But let me return to crematoriums for a moment. Take for example Avraham Miletski’s crematorium in Kiev, Ukraine. Built only twenty years after the end of WW2, this structure is often lumped into the cold war Brutalist basket when in fact it is something far more remarkable. It is a genuine portal to the something like the idea of death. I have written before of Francisco Salamone’s cemetaries, also concrete and at least neo Brutalist. http://john-steppling.com/2015/11/the-engineers-anxiety-or-rejecting-the-goddess/.

Crematorium Heimolen. Sint Niklaas, Belgium. KAAN Architecten.

When I read back over that posting, it is not surprising that Antonioni and Pasolini are both featured, as is Manfredo Tarfuri. There are linkages here, buried and mysterious, but clearly in some way indelible. Ken Worpole, in a sort of terrific book on the architecture of graveyards and departures, begins his book with a quote of Adolph Loos…

“When we find a mound in the woods,

six feet long and three feet wide,

raised to a pyramidal form by means of a spade,

we become serious and something in us says:

someone was buried here. That is architecture.”

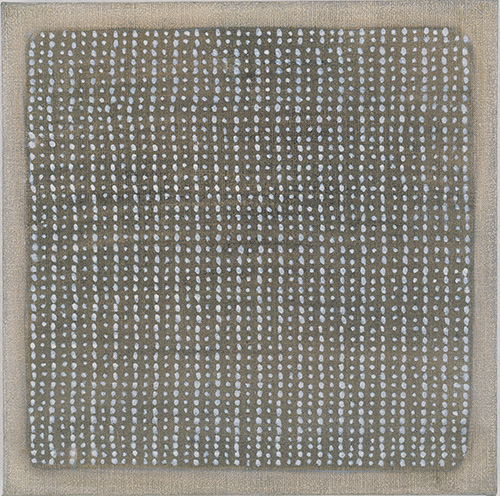

Agnes Martin

It is not surprising that one of the first buildings mentioned in Worpole’s book is Sigurd Lewerentz church and crematorium near Malmo, Sweden (which I also posted about a couple years back). The Lewerentz church is a minor classic and a work of some perfection, really. But the issue with all burial sites, from Pagan Rome to southern Sweden or metropolitan Tokyo, is that (to quote Lewis Mumford) “Modern industrial design is based on the principle of conspicuous economy [but] the bourgeois culture which dominates the Western World is founded… on the principle of conspicuous waste.” Today, in the shadow of a Trump presidency that has forced the white bourgeoisie of the U.S. to confront a pathology of their own which had been kept comfortably hidden (or not so comfortably) for five or six decades at least. Much as the corpse has been kept hidden…in some fashion because it is neither human nor waste (Mary Douglas).

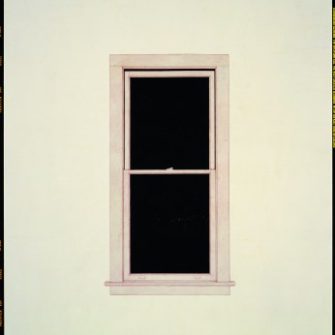

Toba Khedoori

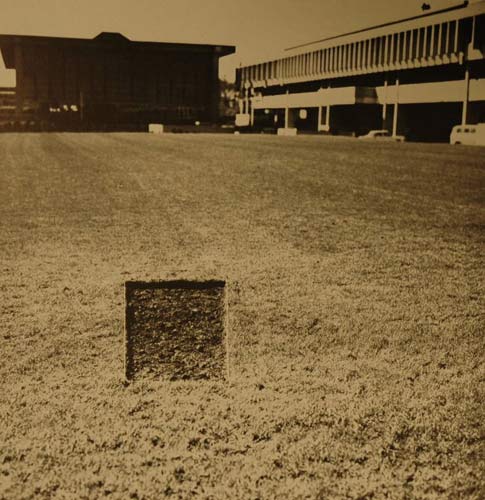

Jan Dibbets (Vancouver 1969).

“…what appealed most to Soane and his contemporaries was the fact that tombs needed no light and air and, as such, they were the perfect vehicle for the romantic classical architectural imagination. Designed for the dead, they required nothing in the way of what, today, we would call “services”: no windows, no ventilation, no heating, no plumbing. They could thus be formed from the basic building blocks of the language of classical architecture, such as the cylinder or pyramid. Here was a first-rate opportunity for Regency architects to indulge with impunity in the re-creation, if on a generally smaller scale, of the great classical mausolea (the word comes from the magnificent and hugely influential tomb of Mausolos at Halicarnassus; you can see a miniature version of this, one of the Seven Wonders of the World…”

Jonathan Glancey

Steven Tourlentes, photography (Parchman, MS death house, 2007).

I am also reminded of the extraordinary photographs of U.S. prison death houses by Steven Tourlentes, taken at a great distance and at night. And these in turn feel related to the work of Trevor Paglen, and his photos of secet US military installations. This sense of the morbid seems activated, in a sense, by that quality of mindlessness found in purposeless geometric accumulation. But also the uncanny and disturbing knowledge that such secrecy (as Paglen’s work specifically isolates) is anti-human, it is the failure of the social. And somewhere Lewis Mumford said something, too, about technique (meaning partly just technology) excuses or covers over the social failures of society. I cannot escape at all these days the growing identification of Trump with a death’s head. I refrain from dwelling on this for obvious reasons, but also for ideological reasons. If Trump is the leering face of death, gilded in imitation gold (feces), then Obama is the boatman on the River Styx. Or the consigliere to Satan. His is the sadistic constipation of gratuitous meanness. The vicious silence afforded Obama’s presidency by liberal America is probably more pathological than the election of Trump.

John Soane. Lecture drawing for Mausoleum of Hadrian.

It was D.H. Lawrence who noted the penitential quality of solitary walking. Worpole notes in relationship to the anonymous crosses of the mountains of central Europe — crosses that Lawrence wrote about in one of his travel essays. The lonely isolated walking figure is the subject of many, perhaps a majority, of Chinese paintings from the classic period. The figure in the landscape — a figure that Beckett was acutely aware of, and which is always looming around the edges of all of his plays. Adorno and Horkheimer, of course, saw Odysseus as the figure, the stranger, in the landscape. The exile returning. Ondaatje transformed Billy the Kid into a allegorically threadbare Odysseus in his short novella, or prose poem. It is possible that the collective imaginary of the U.S. is the most road obsessed in history. And one cannot approach the idea of roads and trips — or journeys — without knowing there one will meet death. One may not die, of course, but the meeting is the point of the travel after all.

Toba Khedoori (LACMA)

There is something worth examining in how architecture and allegory co-exist, in a sense, and how that shapes and is shaped by Capital and by technology. The society that became a car society (and its not an accident, I suspect, that Hitler was so entranced with his autobahn) is one in which the penitent no longer has space. The solitary figure, one who in earlier societies would provide for a time, a period, in his or her life for reflection — a transitional period that usually came after adolescence. Young adulthood, and this became increasingly codified and managed with institutional learning and the propaganda of expectations. That capital is geared to instrumental management is obvious, but that is far too facile. It is not just management but also a cooperation with domination. A collaboration with domination. The colonial era remains so profoundly under studied exactly because it never ended.

Accra Youth Boxing, 1920s. Deo Gratias photography studio.

Zean Cabangis

The mythology of the open road in American folk culture (and later in advertising and branding) followed on the guilt and savagery of Manifest Destiny. That sense of space, of expansion, was something that both Melville and Conrad both finalized in the sea. Those land bound authors of penitence, from David Goodis to Highsmith to Chandler — all in their own way were dealing with the tensions of destination. Aldo Rossi’s Mausoleum in Modena, Italy, is another example of the geometric repetition meant to nullify the process of putrefaction. Repetition then, repurposed as a meditation on that which is there when destination is not.

Destination and death share a good deal. And perhaps there is something so haunting in Agnes Martin because her mania drove on this more and more perfected absence. And that is the organic path to the adventure of death.

Drawing of John Soane by Sir Francis Leggatt Chantrey, pencil, 1820s.

“The spectacle atomizes and diffuses itself throughout not only the social body but its sustaining landscape as well. As Debord’s former comrade T. J. Clark writes, this world is “not ‘capital accumulated to the point where it becomes image,’ to quote the famous phrase from Guy Debord, but images dispersed and accelerated until they become the true and sufficient commodities.”

Mckenzie Wark

The anal sadistic society of purposeful blindess, or rather purposeful turning away. The biological vision is fine, it is the practice of manufacturing metaphor and allegory that is in a kind of stasis. The aerobics teacher on a treadmill, or a stationary bike, has replaced the figure in the landscape. The solitary walker. The exile — is now running in place. That such a living symbol can be so ignored speaks to opaque vision of the constipated sadist. The bourgeoisie today, in the U.S. certainly, live metaphorically arid lives, and walk through landscapes of corporate created blandness. And this stultifying and jejune distracted state is the normal — and worse, it is also inescapable.

Crematorium, Kedainiai, Greece. Architektu Biuras (Dezzen photo).

Image circulation is so exhaustive, now, that beyond just the repetitive sameness of the images, is the weight of a familiarity that has become intolerable. Looking away is the safeguard to a mental fatigue born of familiarity, of routine, and often a routine marketed as its opposite. Everything is *new* or *innovative* or in some fashion the next big thing, a thing that must be bought, usually. It is never new or innovative (a word that has lost meaning) or any of things advertised. It is, even for those not economically participating, a burden and psychological weight to be endured. And this quality of bland monotonous routine is pernicious. The rise in surveillance, as I have said before, is exempt from actually working. Surveillance may well clock everything everyone does, but not in the practical ways that one might think. The data begins to feel interchangeable. If you or your neighbor buy this or that brand of detergent…what does it matter? All that matters is that the data is collected. It is the collection of it that matters. That the collection is then stored. The entire pantomime of control serves its purpose by just existing. The facticity of stored data, vast almost uncountable numbers of data, bytes, is a kind of wan symbol of power and control. But it begs the question, or starts to beg the question, of what we mean by control and power. And this is a question, and a lesson, that a dozen contemporary thinkers have grappled with in varying ways and with varying vocabulary. For this is a source of cognitive dissonance in thinking, now. One of the sources. The terminal model of computer logic is an end game for Capital — at least in the way that technologies always creates contexts that kill off one practice or discipline and open the door to others. Or, usually. And perhaps techne is now at the end of its usefulness.

Sun Yanchu, photography.

One of the enduring tropes of Eurocentric white supremacism, and its Colonial expression, is the idea of the colonial subject as inferior and borderline. A savage in other words. The Western press and media never tire of the Orientalist cliches of African dictators, or South American caudillios, or sadistic Arab potentates. In reality the most deranged and unfit leaders of the last two or three hundred years are found in the Western ruling class. The ruling class erase their own infirmities and eccentricities while always hugely exaggerating those of the subaltern. And it is this fact, the deficiencies of the western ruling elite that is a foundational element in the distortions and nearly hallucinatory narratives of the West.

“There is an irreversible evolution from savage societies to our own: little by little,

the dead cease to exist. They are thrown out of the group’s symbolic circulation.

They are no longer beings with a full role to play, worthy partners in exchange,

and we make this obvious by exiling them further and further away from the

group of the living.”

Baudrillard

Treptow Crematorium, Germany (Axel Schultes and Charlotte Frank architects).

Against this data driven system of control, or pseudo control for the bourgeoisie, runs the evaporation of symbol and metaphor. In a sense this is what Bachelard wrote about regarding fire…

“Contemporary science has almost completely neglected the

truly primordial problem that the phenomena of fire pose for

the untutored mind. In the course of time the chapters on fire

in chemistry textbooks have become shorter and shorter. There

are, indeed, a good many modern books on chemistry in which

it is impossible to find any mention of flame or fire. Fire is no

longer a reality for science. Fire, that striking immediate object,

that object which imposes itself as a first choice ahead of many

other phenomena, no longer offers any perspective for scientific

investigation.”

Gaston Bachelard

Arpais Du Bois

The Treptow Crematorium, in Germany, is very popular. It is also, I admit, a very effectively designed building (albeit resembling a set from Game of Thrones). It is borderline kitsch epic, or kitsch profundis — but make fun of it all you wish, it is still a very fine bit of architecture (I think). It may not be a great Crematorium, but as a building there is a quality of intelligence at work. And that is another issue, I believe. The idea of architecture often seems separated from the idea of the construction of buildings. What I think I like about the Treptow building — the main building anyway– is that those pillars impede not just one’s view, but they impede walking. And perhaps that is a very true gesture by the architects. The tendency to make open spacious and tranquil Crematoriums is not exactly wrong, but it begins to feel artificial. The experience of grief is reduced to a saturday afternoon yoga class. The Dutch include espresso bars in their Crematoriums. I think this is also rather correct somehow. My point though, really, is that the blinkered and shuttered psyche of late capitalism is one that has trouble remembering the physical world is not abstract. And such amnesia, in a sense, is why the dead in Yemen or Syria or Libya don’t count. Or rather they count abstractly. The landscape of the contemporary westerner is one of generic blandness passing itself off as, well, any number of things. And in this generic repetitiveness the fact of death is not ignored, but transformed. Death of a loved one becomes more about the one still living. Suffering then is only MY suffering, and my suffering needs a shot of espresso just now. Unconsciously the best architecture of today is that which was created intuitively. I can’t prove that of course, but it is my strong feeling. Intuitive and unconscious .. architecture had to adjust itself to recapture something mysterious. Something uncanny.

John Atkinson Grimshaw

Allow me a longer quote from Worpole on the Highgate Cemetery in London:

“The Egyptian Avenue itself is flanked by a series of burial chambers, whose formidable metal doors bear the symbol of an inverted flaming torch, a traditional image of a life extinguished, and, even more unusually, contain keyholes that are also upside down, in line with the same reverse symmetry. The Avenue, also known as ‘The Street of the Dead’, leads to the Lebanon Circle, an extraordinarily remarkable piece of excavation and design, in which a ring of inner and outer catacombs were created around an existing Cedar of Lebanon tree, which predated the cemetery itself by 150 years. This circle of tomb chambers echoes the terraces of Etruscan tombs at Cerveteri in Italy, though nearly 3,000 years separate them.The elision between Victorian funereal culture and that of ancient Egypt, seen also at Abney Park, and in many other cemeteries of the period, is interesting, part of a stylistic enthusiasm known as the Egyptian Revival, stemming from the enormous archaeological interest in ancient Egypt in Europe from the eighteenth century onwards, with its associations with Freemasonry and repertory of symbolic forms and imagery, which Family tombs in a circular terrace in the Lebanon circle at Highgate Cemetery, London.

became stock items in cemetery architecture, including pyramids, obelisks, flaming torches and sun motifs.”

Barnett Newman

I made note at the top of the failures of cultural criticism that reject class based analysis. The shaping of western consciousness is little separated from its colonial conquests. Napoleon in Egypt, at the end of the 1700s -this spurred the great wave of Orientalism in Europe. David Cannidine (quoted by Worpole)…

“…those great mid-Victorian cemeteries

– Highgate and Kensal Green in London,

Undercliffe in Bradford, Mount Auburn in

Boston and Greenwood in New York – were

very much the Forest Lawns of their time,

in both their expense and their status

consciousness. For these romantic, rural

retreats were essentially an analogue of

romantic, rural suburbia. Their careful layout,

with greenery, gardens, gently curving roads,

and restful, contrived vistas, was exactly

reminiscent of exclusive, middle-class building

estates like Headingley or Edgbaston.”

Robert Ryman

Donald Judd

Gaston Bachelard, in his rather remarkable book The Psychoanalysis of Fire, writes of fire…

“Among all phenomena, it is really the only one

to which there can be so definitely attributed the opposing

values of good and evil. It shines in Paradise. It burns in Hell.”

He then adds, in the next chapter..

“Modern psychiatry has made clear the psychology of the

pyromaniac. It has shown the sexual nature of his tendencies.

On the other hand it has brought to light the serious traumatism

that a psyche can suffer from the spectacle of ~ roof or haystack

that has been set on fire, from the sight of the great blaze of .fire

shining against the night sky and extending our over the broad

expanse of the ploughed fields. Almost always a case of incendiarism

in the counuy is the sign of the diseased mind of some

shepherd.”

Forest Lawn, Glendale California.

So then, the growing appeal of cremation in the West is probably not an accident. When the liberal westerner cites environmental concerns, such sentiments for the welfare of earth rarely rise to the level of voting against war or an education of self that would make socialism a necessity, it doesn’t even rise to the level of giving up meat (or at least factory farming)…no its more on the level of Im buying organic lettuce and am thinking of buying a Prius. No, cremation is growing in appeal for deeper and more profound reasons, I suspect. And I think the disposal of the dead is not insignificant topic. If the colonial era of tombs and mausoleums (mostly in Great Britain and France, but also Italy and Germany and Spain) gave way to gradually to the neo Victorian cemetery (or lawn cemetery), which found fertile soil, as it were, in the U.S., it was aesthetically and perhaps psychoanalytically, a collective anal sadism. The encouragement is always to hoard in Capital. In an era of financialized capital, cremation feels more digital somehow, and maybe even risk averse. Burn it, and its gone. My prediction is for a cyber crematorium very soon. One can watch on your Mac book as a loved one is sent off to a better place, complete with analytic graphs showing heat, decomposition, ash volume, etc. Maybe I should go Kickstarter and develop one. The release that comes from cremation is also periously close to anonymous — something the narcissism of the West is uncomfortable with. Brand identifying the ash is a project I am sure someone is at work on. But the real issue here is the way in which body disposal is ambivalent. Burial or cremation. The second period of the anal phase is voiding — but the voided material is then lost. And the cremated body is then lost. The body in the tomb or grave is always there (in theory). This loss is a source of ambivalence. The enormous rise in films featuring grave robbers is not an accident, again. It is also another aspect of the Zombie phenomenon. The walking dead. Or, the running dead, now.

The geometric repetition found in so much burial architecture is, I think, because it is in this repetition that the blank space of loss is so easily and acutely expressed. Donald Judd, and Robert Ryman and Carl Andre all touched on the basic core sense of absence in repetition. The geometric patterning of a majority of crematoria always ends at the oven, as it were (and it should be noted that embedded in all this is the echo of Nazi death camps, much as showers, as a word, has not been the same since WW2). The blank space of the incinerator. And that is the one place out of sight — the one place the West cannot tolerate the social. India, on the other hand, if you’ve ever been to Benares, is a place of public cremation. The ash floats down over the city all day from the morning burnings on the Ganges. Things don’t get more social than that, I suppose.

Gaston Bachelard

The West cannot rid itself of its ghosts. That is the problem with advanced capital as it looks to double down on its already failed narratives. A genocidal and Imperialist nation is going to be at odds with body disposal, regardless. The status quo…for death and burial, since early 20th century, has been Forest Lawn. And the important thing to know about this real estate venture of Hubert Eaton, in Glendale, California, is that it emphasized conformity. No family could deviate from the norm. No gravestone or memorial could stand out. The idea was to air brush death out of the equation. The bourgeoisie in the U.S., the white bourgeoisie, had found their final resting place. For a while. And the cornerstone (sic) of this was conformity.

As Ken Worpole described Forest Lawn…“The cemetery ethos articulated here, an ironed out mixture of picture-book philhellenism and Sunday School theology…”

This was death as Norman Rockwell would paint it. But the anal sadism is there. The caskets were steel and concrete backed. Time is erased. There are no mounds of earth, and in theory, no bodily decomposition. As Worpol put it, nobody dies, they are just transplanted. It is telling also that the only decoration at Forest Lawn are kitsch copies of Michaelangelo’s David, and the like. So the Disney aspect is present. It IS southern California after all. But the ultimate point is that behind the faux tranquil suburban fantasy, the Rockwell or Kinkade kitsch aesthetics, there resides a nasty mean spirited exclusionary and anti social ethos. There are, even if not many, poor people at Pere Lachaise. Not at Forest Lawn. The social is banned. The poor are banned unless they magically come up with *pre need* purchase money. The ‘Memorial Park’ is not open to the public.

Kesang Lamdark

(Buddha Shakyamuni, 2009).

“Fourier long ago exposed the methodological myopia of treating fundamental questions without relating them to modern society as a whole. The fetishism of facts masks the essential category, the mass of details obscures the totality.”

Mustapha Khayati

The aesthetics of the particular is an aesthetics of submission or capitulation. The system always provides an alibi. See, they say, we do criticize and police ourselves. Except that behind all of it is the ever mounting tensions of denial and deep repression. And the result is to disappear half the planet from consideration.

Aesthetically, the figure and reality of death is always the subtext of any artwork. And it is partly this that makes rational analysis of art so impossible. For there is always a *more*. I conclude with a few odd linkages between fire, purification, sacrifice and narrative. Jean Paul Vernant pointed out the curious nature of the Prometheus story — and Prometheus occupied an entire chapter of Bachelard — for Zeus never forgave Prometheus for giving men the meat of the sacrificed animal. And hence he hides his divine fire from mortal men.

Devin Leonardi

“It is because Zeus never forgets for an instant the trick Prometheus played on him by giving men the meat of the sacrificed animal that he decides henceforth to deny mortals his (heavenly) fire. It is because he sees the fire, secretly stolen by the Titan, burning in the midst of the humans that he counters this new fraudulent gift that men have received by offering them this third and last fraudulent gift, this “opposite of fire;’ the first woman. “

Jean Pierre Vernant

The gift of ambivalence and ambiguity. And fire mediates the entire story. The myth of Prometheus resonates throughout the literature of psychoanalysis because it is so ambivalent and because it presages other myths. One of which is that of Narcissus.

But let me end with Bachelard…

“The science of electricity in the eighteenth century offers us in this respect an indispensable mine of psychological observations. It should be particularly noted that electrical fire, even more perhaps than ordinary fire, which had then been relegated to the status of a banal phenomenon without psychoanalytical interest, was a sexualized fire. Since it is mysterious, it is clearly sexual. Concerning the idea of friction, of which we have Just pointed our the obvious primary sexuality) we shall again find applied to electricity all that Ive have said about fire. Charles Rabigueau, “Lawyer, engineer, holder of the King’s privilege for all his works on Physics and

Mechanics,” wrote in 1753 a treatise on “The Spectacle of Elementary Fire or A Course in Experimental Electricity”. In this work one can see a kind of reciprocal of the psychoanalytical thesis that we are putting forward in chis chapter to explain the production of fire by friction. Since friction is the cause of electricity, Rabiqueau will develop an electrical theory of the sexes on this theory of friction…( )…We have perhaps already tired the patience of our reader; but similar texts, which could be extended and multiplied, tell us quite clearly of the secret preoccupations of a mind which claims to be devoting itself to “pure mechanics.” One can see, moreover, that the center of the convictions is not at all the objective experiment. Everything that rubs, that burns, or that electrifies is immediately considered capable of explaining the act of generation.”

Fantastic read. thank you. You put into words what I feel in my gut — that the flaws in social discourse go deep and fundamental . . . and everything now is running on a sort of mad autopilot, and there can be only one possible outcome.

An impressive share! I’ve just forwarded this onto a co-worker who has

been conducting a little homework on this. And he actually bought me lunch simply because I found it for

him… lol. So allow me to reword this…. Thanks for the meal!!

But yeah, thanx for spending time to discuss this matter here on your web page.