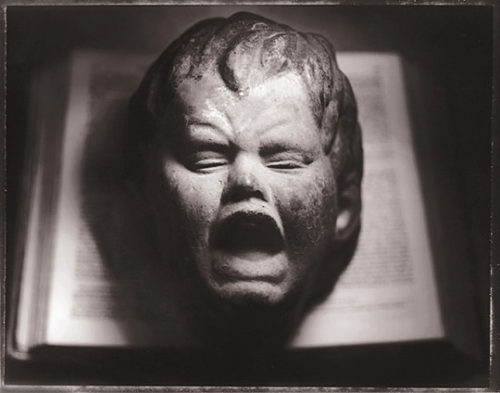

Sean Kernan, photography.

“Kafka’s world is a world theatre. For him, man is on the stage from the very beginning.”

Walter Benjamin

“To take upon us the mystery of things”

Shakespeare (King Lear)

“Leopards break into the temple and drink all the sacrificial vessels dry; it keeps happening; in the end, it can be calculated in advance and is incorporated into the ritual.”

Kafka (Zurau aphorisms)

It is important, I think, to see the heterogeneous and often contextually isolated examples of mass culture that subvert expectations and rise to the level of something other than their stated intention, or the intention of the producers and distributors of this entertainment product. A recent example was an episode of the UK crime franchise Endeavour, directed by Jim Loach (Ken’s son). It is so singularly good that it almost feels as if it doesn’t even belong to this show. And in a way it serves to to raise questions about the reading of narrative and the meta narratives of 21st century mass culture. For this ninety minute episode can stand by itself as a strange commentary on exactly the reasons this franchise is popular. Loach’s direction deconstructs the idea of nostalgia, and of class — although the episode in question is really more about the treatment of class and memory as it is manufactured by the entertainment corporation ITV. Loach has managed to critique the very idea of this franchise, of manufactured histories and of public memory as it exists in mainstream entertainment. (the episode in question is #4, of season 4). But its more just the elegance and intelligence of how Loach directed each scene. The pace, the editing, and the placement of the camera (every set up of police and suspect, for example, draws on archetypal noirish paranoia, but without making these images at all about style). And the cumulative effect is unsettling because it is both unmoored from the narrative, and simultaneously constructs a new narrative of genuine poignancy. And most remarkably, there is nothing in the least ironic about these samplings of post war noir.

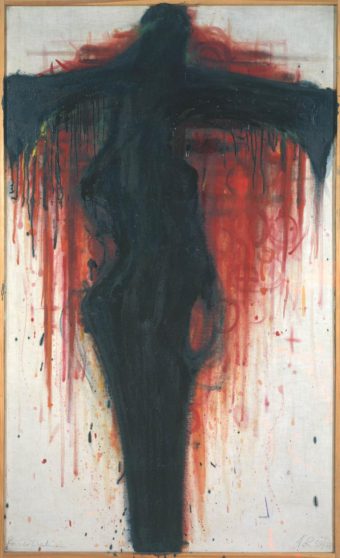

Arnulf Rainer

“…there is the air of the village, as with all great founders of religions.”

In Kafka the judge turns into the defendant and the trial itself is the punishment. And yet, Benjamin knows all the ways one can miss the point of Kafka. For Kafka was not a theological writer, but rather a mystic. Stories were significant because they postponed the future. Today, theatre seems more important than perhaps any other medium, but also more impossible. The world of mass culture today is one in which the characters in TV and film have arrived at a strange intersection between advertising, propaganda, and a kind of embarrassment — and I’d have liked to say *shame* but it is too strong a word. The most popular film, critically anyway, this year is La La Land. The second feature by Damien Chazelle, a Harvard grad and son of a history professor. Critics have reached often for their thesaurus in lavishing this project with praise and near adulation. But then it is the most onanistic and masturbatory film Hollywood has produced in a generation. It is also the whitest. And that is the key. Chazelle’s first film, Whiplash, about a drummer {sic} at a music conservatory, was a strange re-whiteing of jazz history, with Buddy Rich of all people looming as the godfather of that blackest of all art forms. The current hit, with Ryan Gosling and an anorexic looking Emma Stone, is even whiter and even more revisionist about music. But that is all beside the point. The point here is that Chazelle represents a kind of new non narrative pastiche form. There is no story unless one thinks 1st grade readers contain stories (See Jane run, run Jane run). The overriding sense of La La Land is that of cuteness. Several critics used the word ‘aching’ to describe the romance. The need to see some phantom emotion in what is a film without emotion is very key the success of this film (Slumdog Millionaire is close cousin in this sense). There are no characters as one has come to understand that term. There are celebrity movie actors playing at being romantic. The constant references to everyone from James Dean to Louis Armstrong to pulp TV is the *real* story. And hence it is a strangely antiseptic film where the sampling isn’t even real. What is referenced are references to references. In other words it is a film of cliche. It’s not about cliche, but rather it embodies something of the experience of being presented with an endless stream of cliches. It is the meta cliche.

Bob Fosse (circa Sweet Charity, 1969).

Eikoh Hosoe, photography.

Now, I think it is worth looking at La La Land not just in the shadow of Bob Fosse, especially the Fosse of the sixties, but also in light of Kafka, and in particular the Kafka of the Zurau aphorisms. One of qualities that great actors all have is a kind of presentness. Its just that they arrive at it in different ways. I was watching the silly Tom Hardy vehicle Taboo recently (with the fine Stephan Graham and equally fine, if toney, Tom Hollander) and as mediocre as the project and writing, Hardy is worth watching (better is his final scene as the Jewish gangster in Peaky Blinders) because of his eyes. Hardy is not the most intelligent of actors, but he is among the most focused and that focus (for lack of a better word) is arrived at via his look — his gaze — his ocular there-ness. Brando, the most present of all actors, did it through his nervous system, his body, a preternatural grace and physical sensitivity. And this sensitivity is what gave Brando his uncanny femininity, housed in that most masculine of bodies. Hardy lacks the feminine, but his piercing gaze is genuine and it illuminates otherwise boring material. Hardy’s reactions are always born of what he *sees*.

“The dogs are still playing in the yard, but the quarry will not escape them, never mind how fast it is running through the forest already.”

Kafka, Zurau aphorisms

Rudolph de Crignis

An actor like Gielgud found that sensitised presentness through his speech. Derek Jacobi does the same. Listen to Jacobi’s readings of Nijinky’s diaries in the much neglected The Diaries of Vaslav Nijinsky , by Paul Cox (2001). At times Mark Rylance approaches this, too. And Rylance as the Soviet spy in the highly reactionary Spielberg film Bridge of Spies (2015). This is an example of what I mentioned at the top; by virtue of this uncanny sensitivity to speaking aloud, to the recitation of lines, the reactionary is reversed and the only human being in the Spielberg film is the Soviet spy.

Benjamin, writing of Kafka: “The law of the theatre is contained in a sentence tucked away in ‘A Report to the Academy’: ‘I imitated people because I was looking for a way out, and for no other reason’.”

The aphorisms were written while Kafka was convalescing in the village of Zurau. And it is this village which formed the basis for the village K surveys, presumably, in The Castle. Benjamin sees it as both Zurau and as the ur-village in Talmudic legend. And that village is metaphorically the body in which the soul is temporarily exiled. This is the space of allegory. The musty and claustrophobic offices Kafka endured find expression in the pigsy the country doctor houses his horses or (per Benjamin) in Klamm’s back room. And this is the same room in which Endgame takes place. Now Benjamin notes the importance of shame in Kafka, and shame is both a shame in front of others and a shame one feels for others. In the mass culture of today (thinking mostly of film and TV) shame is merely embarrassment — and it is always, for those who can see, an embarrassment for others.

The Big Combo (Joseph H. Lewis, dr.) 1955.

“All of Kafka’s work circles around this one insight: that we are cut off from the true word, which even Kafka himself is unable to perceive.”

Siegfried Kracauer

“In our textbook (john Howard Lawson: How to Write a Script) we learned that the films we loved the most were badly made. That was the starting point of an ongoing debate between me and a certain type of American cinema, theater,and literature, which is considered well made. What I particularly dislike is the underlying ideology: central conflict theory . Then, I was eighteen. Now I’m fifty-two . My astonishment is as young now as I was then. I have never understood why every plot should need a central conflict as its backbone.”

Raul Ruiz

When Kracauer writes of a *true word* he is, essentially, saying that every attempt to identify a thing or name an object of feeling is a mistake or failure. Now, Ruiz, as a young man in Chile, already loved Ford and Joseph H. Lewis and Fritz Lang. But suddenly the *how to write books* were telling him this was all wrong.

Bye Bye Birdie (George Sydney, dr.) 1963.

Ruiz continues…“To say that a story can only take place if it is connected to a central conflict forces us to eliminate all stories which do not include confrontation and to leave aside all those events which require only

indifference or detached curiosity…”

And I would suggest that what Bob Fosse did with choreography was not unlike what Joseph H. Lewis did with film. And part of what they were both doing was to accept that the interior lives of humans were often damaged and the symptom of that damage was boredom. For there is boredom and there is boredom.

“…the criteria according to which most of the characters in today’s movies behave

are drawn from one particular culture (that of the USA) . In this

culture, it is not only indispensable to make decisions but also to act

on them, immediately (not so in China or Irak). The immediate

consequence of most decisions in this culture is some kind of

conflict (untrue in other cultures). Different ways of thinking deny

the direct causal connection between a decision and the conflict

which may result from it; they also deny that physical or verbal

collision is the only possible form of conflict. Unfortunately, these

other societies, which secretly maintain their traditional beliefs in

these matters, have outwardly adopted Hollywood’s rhetorical

behavior. So another consequence of the globalization of central

conflict theory – a political one – is that, paradoxically, “the

American way of life” has become a lure, a mask: unreal and exotic,

it is the perfect illustration of the fallacy that Whitehead dubbed

“misplaced concreteness.” Such synchronicity between the artistic

theory and the political system of a dominant nation is rare in

history. ( ) The reasons for this synchronicity have been abundantly

discussed: politicians and actors have become interchangeable

because they both use the same media, attempting to master the

same logic of representation and practicing the same narrative logic

– for which, let’s remember, the the golden rule is that events do

not need to be real but realistic (Borges once remarked that Madame

Bovary is realistic, but Hitler isn’t at all). I heard a political commentator

praise the Gulf War for being realistic, meaning plausible,

while criticizing the war in former Yugoslavia as unrealistic, because

irrational.

Raul Ruiz

Obama was realistic. Trump is not. And that goes a ways toward explaining the protests.

Emilio Prini

This is, in a nutshell, the fate of mass culture at present. As Ruiz adds a bit later, the same rules apply to real life as are employed in Hollywood — it is the same simulation. Now, I’d only add that the engine driving the repetitive nature of this simulation is the Death Instinct.

Beyond that, of course, it is this quality of structured infantilism that pervades 21st century society. And the structure is that of a Hollywood TV episode. For nothing in society even rises to the level of a feature length film. It is an episode of a familiar franchise. In the case of the critically acclaimed La La Land, there is only signposts directing the audience toward something they might have once understood as a story. In between are musical breaks with indifferent and intentionally amateurish choreography. And as a side bar note, the group dance sequences, of which there are only a couple, are fascinating to compare (in particular) to Fosse or Jerome Robbins, or Michael Kidd. Whatever justifications there might be for the casual (sic) level of discipline, the de-fault commentary on the *idea* of the musical is worth considering. That aside, the problem with the group dance sequences is less the dance skills, and more the lack of interior life in the dancers. The *cute* factor is stillborn… I mean this is a film that can’t even really deliver cute. There is none of the self awareness of even Bye Bye Birdie. In fact Bye Bye Birdie is a useful comparison, for director George Sydney, perhaps unconsciously, but perhaps not, opened the film with 22 year old Ann Margaret against a neon blue screen singing to the audience. It is one of the more erotically charged openings in all of filmdom. But it is also a transitional musical. The Beatles arrived a year or two after and altered pop culture and the marketing thereof, and the traditional Broadway musical was being critiqued as old fashioned while the pseudo new was itself virtually out of date as it arrived. No matter, the film remains a surreal lollipop (as R. Emmet Sweeney put it) and one that was much more about the surface gloss (and the implications thereof) than the story. The difference between Ann Margaret and Emma Stone speaks volumes, however. And the winking irony of Sydney’s film seems sincere (sic) as opposed to the morbidity of the post ironic dullness of the Gosling/Stone vehicle. One is alive and the other is, to be generous, almost dead. Cadaverous. Fecund vs sterile.

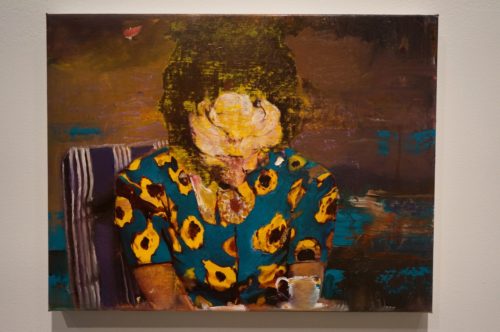

Adrian Ghenie

But I digress. Ruiz speaks of ministry vs mystery. And describes artworks within this dichotomy. Artaud and Villon and Genet and Cage and Pollock and Mishima and Leopold Leo are mystery…the King James Bible is mystery too as is Kafka. Ministry is Gainsborough and Reynolds, Zada Hadid and Norman Foster. The lists are fluid. Another way to look at cultural product in this light is to see what is bourgeois. Not who, but what. Pinter is a greater playwright than Mamet for this exact reason. Robert Walser and Herman Broch are not producers of bourgeois narratives. This is a crude division, but it serves to point out the implications now of commodified culture, of a culture than can no longer step outside of itself. Gunther Grass is ministry and Handke is mystery. The more significant discussion takes me back to Kafka.

“Ministry, public or private,shows itself as a group of men at everyone ‘s service, subject to a schematic organization that attempts to describe each individual role: subject, that is, to a hierarchical order. The hierarchical order describes the respective function of each player in the field. It is available to everybody, regardless of whether or not they are members of the team. There is only one reading, the literal one.”

Raul Ruiz

Francis Picabia (1916)

Hollywood is awash in lawyers. They all write, too. And legal briefs have no subtext. This was told me recently by an old friend who writes film and TV. One of the most haunting moments in all of cinema is in Bunuel’s Robinson Crusoe. It is when Crusoe has been rescued and is leaving the island. He takes a final look back at the receding coastline of the island on which he has been marooned for so long. The sound of his long dead dog barking is heard.

Kafka said somewhere that a story had to be produced in a single breath. This echoes classical Chinese painting in which the work must be done in a single stroke. It is the basis of both Islamic calligraphy and Chinese and Japanese calligraphy — it is also what I believe is found in the tragedies of Aeschylus. In Sophocles there is an inhalation and an exhalation. In Euripides there is now breathing. There is a virtue to breathing, of course. But there is something compelling, in the sense of mystery, in not breathing. Or, rather, in breathing once. From Shakespeare to Joyce the breathing became a hyperventilation. From Kafka, the logic of narrative production was reversing back to silence. Beckett knew this, Handke knows this, Sebald knows this, and so did Pinter.

Man of Flowers (Paul Cox, dr.) 1983.

“On September 4th, 1917 at the age of 34, Franz Kafka was diagnosed with catarrh in the lungs and serious danger of developing tuberculosis, the disease that took his life almost seven years later. Following the advice of his doctor to move to the country, on September 12th Kafka tookan extended leave of absence from his job at a semi-governmental workers’ accident insurance firm in Prague and moved in with his sister Ottla in her home in a small village then called Zürau(now Siřem) in the northwest of the present Czech Republic. Over the next five months, from October 1917 to February 1918, Kafka composed the majority of what are now commonly called the Zürau aphorisms. ( ) After copying the aphorisms from the notebooks onto separate sheets of paper, Kafka also struck through twenty-three of the aphorisms in the collection; however, he struck them through using a pencil whereas the aphorisms were written in pen, which would allow him easily to erase the strikethrough without ruining the aphorisms. The entire collection, including those that were struck through, was copied into a typescript in the late fall of 1920 by someone other than Kafka. Those aphorisms that were struck through were marked with “xx” in the margins of the typescript. The aphorisms were left in this state by the author.”

Ben McFry

It is telling that Kafka sensed that the idea of never finishing anything was part of finishing it. Wittgenstein understood this in the sense that philosophy cannot be systematically concluded. Not anymore. For this is the age of impossibility. At least cultural impossibility. And Kafka signaled the front edges of this awareness.

“As firmly as the hand grips the stone. It grips it firmly however only in order

to throw it all the further. But the Way leads in that distance too.”

Kafka, Zurau aphorisms.

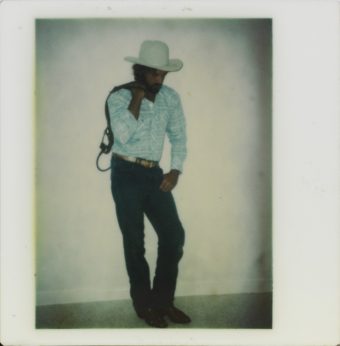

Duane Hanson, photography (Poloroid).

In Kafka’s stories, the quality of fatigue is profound. Doorman and petty officials, functionaries and guards. Shame and guilt permeate the narratives. And it is a guilt never expiated. The unknown nature of every guilt is written illegibly (The Penal Colony). And as the last lines of The Castle echo here…this shame (or guilt) will outlive us. Illegible and yet immortal. In contemporary art the qualities of mystery, of the illegible, are rarely foregrounded. Certainly not in mass culture. I spoke earlier about the embarrassment one feels for others when watching popular film and TV. I often find myself turning away or just stopping when certain scenes appear. A character embarrassed, or shamed. Often without it being the fault of the person being humiliated. And humiliation is perhaps the most common currency of narrative logic today. There is something in the performance of shame and embarrassment that subverts the uncanny and mysterious qualities of theatre and film. Actors being asked to perform shame find it very difficult not to simply *indicate* (as they say in acting class). It is a very sort of pernicious affect.

In the stories of Kafka, every rule from every how-to book on screenwriting is broken. When I taught at the Polish National Film School, I had to give my first year students an assignment to write a scene with conflict. I had no idea what I would have written. Neither did they, really. But for different reasons. But I would often wonder at the idea of conflict. And I would consider Kafka. Is there a conflict in Amerika? Yes, I suppose there is. Maybe. But what is it? In The Trial? Or in The Servant, the Losey film written by Pinter, where conflict is simply class struggle. In Skolomowski’s Shout? The conflict in all of Ozu’s film remains elusive. Once the stakes are raised, as it were, questions of conflict are subsumed. Conflict in Bresson? In Fassbinder? Conflict is everything and nothing when we speak of narrative. And when the student writer is forced to think this way his or her work will fail.

Mary Reid Kelley and Patrick Kelley (Video still, 2011).

A man walks into a room. He switchs on the light but the bulb burns out. The room remains dark. Is there conflict? If that man is an exile, or a mysterious stranger than other characters do not know, then the darkness takes on meaning. What meaning? I have no idea. When an actor such as Tom Hardy walks through a hackneyed boiler plate TV series the meaning is his performance. A performance that is only about itself. Brando spent most of his Hollywood career performing the role of Brando in search of a text. And that was often enough. Brando was tragic. The tragedy was not his, however. Or, rather, it was both his and not his.

“With Kafka a phenomenon bursts onto the scene: the commixture. There is no sordid corner that can’t be treated as a vast abstraction, and no vast abstraction that can’t be treated as a sordid corner.”

Roberto Calasso

John Van Alstine

Orson Welles once said ‘the condemned are so attractive’. Kafka, in The Trial: “Defendants are the loveliest of all. . . . It can’t be guilt that renders them beautiful. . . . It must result from the proceedings being brought against them, which somehow adhere to them.” The truth of what Ruiz calls the simulation of life today is that, as someone said, it is by putting on a mask that one reveals what is hidden. La La Land is perhaps the quintessential Obama era film. I say that because it is more than anything else a film about revisionism. And it is about Hollywood — it is once again an industry congratulating itself. But the revisionism is most obviously about race, but that is almost too easy. It is also about the neutering of radicalism. This is a document of whiteness, as imagined by the white bourgeoisie. And while the idea of romance is reduced to a series of cute-meet set ups, the liberal conscience must appear in the guise of responsibility. The tacit definition for meaning is sacrifice that sacrifices nothing. But the film betrays its own conceits over and over through the sheer lack of wit and awareness. In Fosse’s best work, in film musicals, the ennui of the performer is the real story, or rather the innate fatalism of the dancer’s relatively short shelf life. The abuse of the body, the sacrifice, is off screen. For all that can said of All That Jazz, it stands as a testament to the laws of decay.

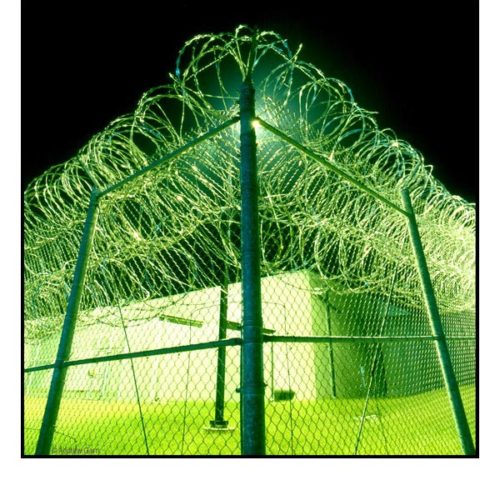

Andrew Garn, photography (CCA fence, prison Nashville TN.)

I’d like to return to Paul Cox. The Australian director has accumulated a body of work that seems relevant in this discussion. I used to screen his 1983 film Man of Flowers for my film students. It is, in its way, a deconstruction of romanticism, but one that borrows from film history without losing sight of his own country’s colonial history. In other words it is not a film about film but a film about history that has been shaped, in part, by film. Echoes of Welles appear, as does the history of painting seen from the provinces. The opening shot is of a Titian (Venus with an Organ Player). The idea of romance here is almost the anti-cute. It is a romance of witholding and doubt. And it is the romance of contemporary wounding and its symptom, masochism. The soundtrack uses much from Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammemoor and there is an operatic quality to the mise en scene. I suspect there are specifically Australian in-jokes regarding the inaccessibility of seeing Titian first hand, but in any event the Titian chosen features the gaze of the organist –furtive and pained. It is a film about symptoms and what they represent. Voyeurism primarily. It is a film that has aged well, in fact. Not a masterpiece — meaning it is no desire to inflate its own ambitions.

Diana Johnstone wrote recently…vis a vis the coming French elections…

“The amazing adoption in France of the American anti-Russian campaign is indicative of a titanic struggle for control of the narrative – the version of international reality consumed by the masses of people who have no means to undertake their own investigations. Control of the narrative is the critical core of what Washington describes as its “soft power”. The hard power can wage wars and overthrow governments. The soft power explains to bystanders why that was the right thing to do. The United States can get away with literally everything so long as it can tell the story to its own advantage, without the risk of being credibly contradicted. Concerning sensitive points in the world, whether Iraq, or Libya, or Ukraine, control of the narrative is basically exercised by the partnership between intelligence agencies and the media. Intelligence services write the story, and the mass corporate media tell it.”

Yves Tanguay

In the U.S. that narrative control is now and has been for a while, the province of the giant communications industry and its brokers on Wall Street and that shadow government that is now referred to as the deep state. To look back only to 1979, if one examines pop culture, is too see Milos Foreman’s foray in the film musical with Hair. Choreographed by the remarkable Twyla Tharp, the very integration of dance affects all the gestures of the film. It becomes a fun house mirror of military rigidity. The knowing winks at the audience, which really constitutes a convention of the American musical form, are more glances of terror. It is wry and menacing both, but it certainly is not ironic. The narrative that Johnstone alludes to above is one that is replicated in La La Land, as a form of seduction. Except, again, it cannot even rise to that. In much the same way the Clinton campaign could not find a convincing way to disguise their smug superiority and dislike of the poor. The idea of out of work youth means having to play in a pop band in the backyard of a Bel Air mansion. This is what constitutes suffering for Chazelle, apparently. He simply cannot hide his smugness.

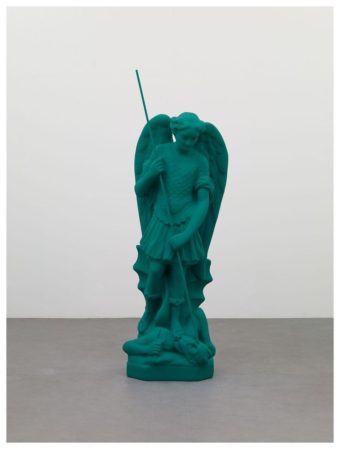

Katarina Fritsch

The narrative of the U.S. ruling class is, then, the de-fault narrative for the entire planet. At least that is the idea those who manufacture it have. The facts are hugely different, but there is still no denying that U.S. mass culture has impacted how people the world over process reality. If even to denounce it. And many tens of millions of people do denounce it, but it has its effect anyway. Certainly the political class from Indonesia to Canada to Mexico to Moldova are aware of American popular culture. And have been so for half a century probably. But the laws of unintended consequences have surfaced, too.

The narrative itself has been so generalized and repetitive that the its effectiveness as narrative is gone. It still works as crude propaganda and through the conditioning that elicits expectation and anticipation, even if only semi consciously. A narrative, a story, has a certain role to play in how we develop — and it has a social role, too. Cultures tell stories to themselves in order to better re-narrate their own stories. The stage world of the Kafka imaginary, that of the incomplete dream, the space of ur-shame, or eternal guilt, has receded to form an unseen backdrop to the now near fascist propaganda of the U.S. state and it has resulted in an American populace that simply accepts war and global suffering as one accepts that (or expects that) eventually all the pieces of the Christmas jigsaw puzzle will fit together. And when they don’t, or some are lost, that’s ok because we have another puzzle right here.

Goya

Edward Curtin, writing of Dylan’s Nobel award begins with a quote from Camus (from his, Camus’, Nobel acceptance speech)..

“Any artist who goes in for being famous in our society must know that it is not he who will become famous, but someone else under his name, someone who will eventually escape him and perhaps someday will kill the true artist in him.”

Curtin adds, on Dylan….

“His masks (personae = to sound through) have served as his medium of exchange. He has been faithful to his tutelary spirit, what the Romans called one’s genius that is gifted to one at birth and is one’s personal spirit to which one must be faithful if one wishes to be born into true and creative life. If one sacrifices to one’s genius, one will in return become a vehicle for the fertile creativity that the genius can bestow. A person is not a genius but a transmitter of its gifts.”

Emily Kinni, photography. (Lobby, Alaska State Prison, 2011).

and then adds…“Do generations of his fans sense a vacancy at the heart of their self-identities—non-selves—as if they have been absent from their own lives…” Most great artists know they aren’t really responsible for their art. They channel it. That is one of the nearly absolute truths of art. The virtuosity of a Rembrandt or Coltrane, or a Beethoven doesn’t fundamentally change this. Its only one cannot be that vessel for the sublime without skills.

Adorno wrote…“Kafka is exemplary for the gesture of art when it carries out the retransformation of expression back into the actual occurrences enciphered in that expression — and from that he derives his irresistibility. Yet expression here becomes doubling puzzling because the sedimented, the expressed meaning, is once more meaningless; it is natural history that leads to nothing but what, impotently enough, it is able to express.”

The second half of that paragraph is both profound and difficult.

“Art is imitation exclusively as the imitation of an objective expression, remote from psychology, and which the sensorium was perhaps once conscious in the world and which now subsists only in artworks. Through expression art closes itself off to the being-for-another, which always threatens to engulf it, and art becomes eloquent in itself; this is art’s mimetic consummation. Its expression is the antithesis of expressing something.”

Martin Johnson Heade

Artworks are mimetic (Adorno’s version anyway, for the purposes here) and yet always also dialectical. Today, so pervasive is a kitsch aesthetic, and its not even kitsch, it kindergarten kitsch, that all expression is almost by necessity vanity. Adorno was keen to point out that if an artists expressed work is only a reflection of his inner soul, the result would be (what he called) a blurred photograph.

“The enigma of artworks is their fracturedness. If transcendence were present in their fracturedness, they would be mysteries and not enigmas; they are enigmas because, through their fracturedness, they deny what they would actually like to be.”

Adorno

He is speaking of Kafka, in the above. And adds that artworks are like broken stelae in graveyards — their perfection, or completion has been lopped off. But his most penetrating observation (at least for us, today) was…

“Kafka, in whose work monopoly Capitalism appears only distantly, codifies in the dregs of the administered world what becomes of people under the total social spell more faithfully and powerfully than do any novels about corrupt industrial trusts.”

Kafka resisted, in his language, falling into the traps of prevailing myth. It is what separates him from lesser writers. The hardness of (per Adorno again) his archaism serves to illuminate the disenchantment of contemporary life. That so much of mass culture today is both childish and flaccid, both technically and spiritually, is the inheritance of late Capitalism. The reified world was already chronicled in Kafka and it may be that everything that comes after are indeed just broken stelae.

I tried writing a longer comment the other day and it got erased by the capcha timing thing which frustrated me so I gave up; just want to say now that this piece was excellent and I really enjoyed it and hope you know it’s appreciated and that people *do* read these even if they don’t attract dozens of comments like something about the nobel prize. keep up the great work comrade, cheers.

yeah, sorry about that captcha thing. It seems we are having a hard time fixing it right. Just cut and paste the comment. Im sorry to have missed your longer comment.

Of what

wounding

is masochism

a symptom of?

I don’t understand

I must know

Thanks Mr. Steppling