Daido Moriyama, photography.

“The view only changes for the lead dog.”

Norman O. Brown

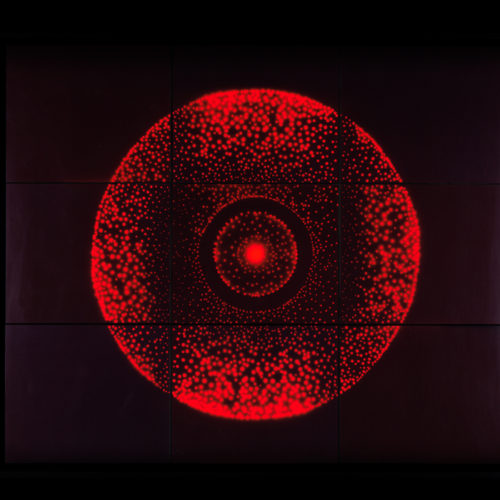

“The more I looked at fractal patterns, the more I was reminded of Pollock’s poured paintings. And when I looked at his paintings, I noticed that the paint splatters seemed to spread across his canvases like the flow of electricity through our devices.”

Richard Taylor

“A role is not a role. It is social life, an inherent part of it. What is faked in one sense IS what IS the essential, the most precious, the human, in another and what is most derisory is what is most necessary. It is often difficult to distinguish between what is faked and what is natural, not to say naive (and we should distinguish between a natural naivety and the naturalness which is a product of high culture).”

Henri Lefebvre

John Berger writing of the painting in the Chauvet Caves;

“Their space has absolutely nothing in common with that of a stage. When experts pretend that they can see here ‘the beginnings of perspective’, they are falling into a deep, anachronistic trap. Pictorial systems of perspective are architectural and urban – depending upon the window and the door. Nomadic ‘perspective’ is about coexistence, not about distance.”

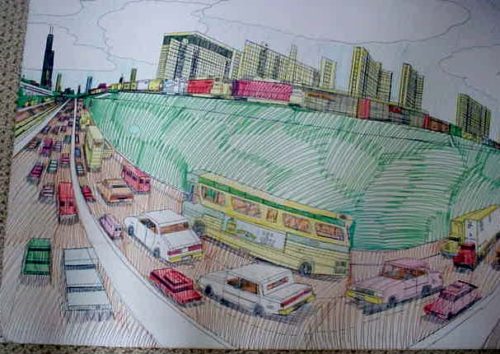

I have been thinking a lot about cities, today, in both Europe, and in North America. Perhaps because I rarely go to the city anymore. One thing is noise. The silence of the world as it must have existed for those anonymous painters of the Chauvet caves is very rare today (well, THAT silence is gone), if not impossible to find, even in the most remote parts of the world. Where I live there are few people. It is farming country, mostly. I hear tractors often, and a few automobiles or trucks. Rarely do I encounter actual traffic however. In winter, now, I hear the ice. I hear the winter sounds. The constant low level struggle of the fjord and the ice. Norway is one the most sparsely populated countries in Europe (only Iceland has a lower population density) so I have become accustomed to far less talk than when living in the U.S. Talk tires me out, now. When I teach I am exhausted afterwards. And the modern idea of city is one that necessitates a good deal of talking.

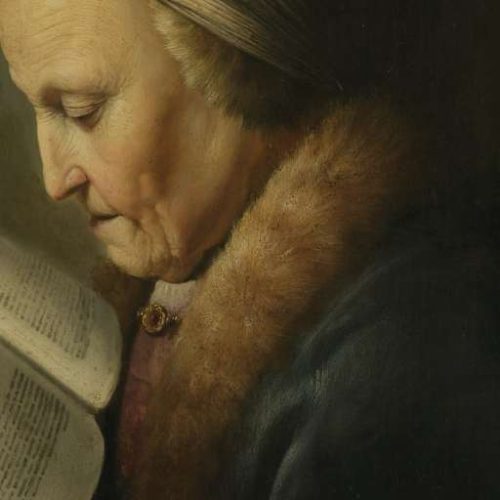

Gerrit Dou (1631). Detail.

Increasingly leisure has become more aggressive and violent. The play has gone out of play, replaced by substitute forms of domination. Leisure is treated as a training exercise for domination. In the U.S. today there is less actual leisure time and that which exists is ever more the development of skills that serve to reinforce hierarchical systems of subjugation.

Obsolete skills are repurposed as entertainment. And within such repurposing there is a partially hidden layer of self domination. The plethora of reality TV often focuses on tests of mock courage and survival techniques, of returns to some fantasy past that is part nostalgia and part self abasement. Except it’s a sort of mock self abasement that is then, by virtue of its counterfeitness, all the more self abasing. The privileged 1% today, and their minions and clerks, put poverty to use as a propaganda tool to demonstrate the need to cleanse the squalor produced by lesser people. Except again, the filty poor are also fetishized and eroticized for service in psychological and social/erotic bantustans of leisure. And this is almost no longer propaganda, for the ruling elite make little effort to hide their sense of superiority. And the clerk class, the managers aspire to a proximity to the segregated pavillions of wealth. No longer do this class even dream of actual elite wealth, they are content to not be intwined with the poor and their *ugliness* even if it means bowing and scraping before those with wealth, and never uttering any expression of dissent.

Jannis Kounellis

“Within every class-based society the constraints that one class imposes upon another are always a part of the inhuman power which reigns over everything. On that level, the individual sees himself ‘divested of his real individual life and filled with unreal universality’.”

Henri Lefebvre

The liberal managerial class, the white collar professionals, those who own a condo, maybe, but live in the major urban centers of the U.S.; these are people for whom the American dream is just access not to privilege per se (except relatively speaking) but to the privileged. It is amazing how readily these clerks and stenographers will express their respect. The rich are referred to as *Mister* or *Misses*, or sir or whatever. The proles are hey you, or Jake, or Tom, that guy. This is the self loathing of the liberal class and the necessary hatred of the poor.

Lauren Marsolier, photography and construct.

You will hear pro athletes, black and white and other, all refer to owners of pro teams as Mister so and so. Never ever does Dan Snyder get called *Dan*.– its always Mister Snyder. Mr Bennet, Mr Angelos, Mr Steinbrenner etc.

But back to this idea of Nature and its relationship to alienation. For this is something that infects architecture certainly. But the manufacture of alienation is built into ideas of pleasure, as well. And to sexuality. And part of the multiple levels or layers of identification that surround political figures and celebrities, is both a critical factor in this, but also its effect.

“A true noun, an isolated thing, does not exist in nature”.

Ezra Pound

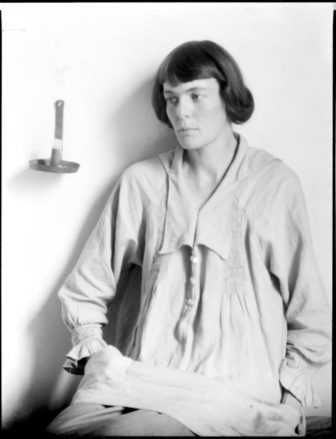

Hilda Doolittle

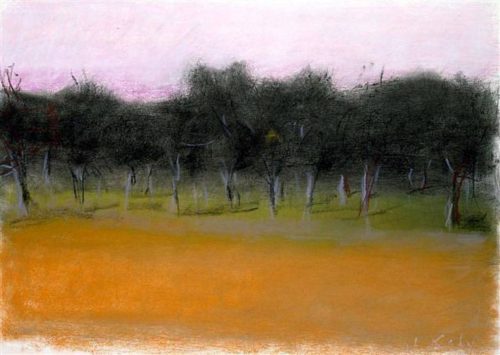

Wolf Kahn

And this is important I think. The effect. The writer or painter achieves an effect, often of novelty (there is no more pernicious trend in arts than valorising novelty or, put another way, originality). Much of the best of Asian aesthetics has to do with erasing effect, not emphasising it. And to return to Pollock for a moment; the effect of Pollock (and Rothko, and even Kline) is minimal. For when I think of effect, I think more of that which adheres to message. The message always has its effect. Norman Rockwell has an effect, and in his case the effect and the message are pretty superficial. The message and effect of Hopper is greater, but Hopper is great because he subverts his own effect. It is the mysterious uncanny memories evoked in Hopper. The philistine will write that Hopper is about (pick adjective) loneliness, say. But this is like saying Tolstoy was a great writer of war scenes. Or that Pinter had a great *ear*. The appeal of the bourgeois critic is always to something everyday, a certain kind of everyday. The parochial everyday. It imparts the message that one’s boredom has value and importance. It does not say boredom is the by product of a system of exploitive labor and repetition. It is the generalizing view that extracts banality and praises it against a backdrop of ahistorical sameness.

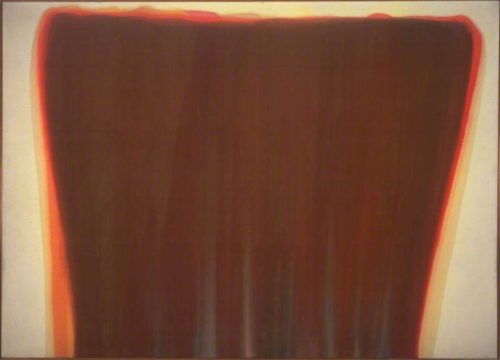

Kenneth Noland

But this becomes semantic in a sense. And it begs the defining of *affect*. But what Duncan really meant was that the real poem was there beneath the poem that got everyone’s attention. Its like pre click bait click bait. Originality or novelty or innovation in the arts is equivalent to click bait in internet marketing. But in a way this is a logical progression from the shifts away from Nature as a subject for art, and toward man as the ultimate subject. All the way back to the 1930s Adolph Loos wrote that “the purpose of art is to take man further and further, higher and higher, to make him more like God.” In poetry, when Bly began critical writing in his own quarterly(ish) The Fifties, he was criticizing poets he liked, but who he saw as awful influences (Auden, Eliot, and even Milton). Though he reserved his deepest scorn for academic poets. He specifically noted the turn from, say, Spanish surrealists (Neruda is always embedded in Nature, as is Lorca and Vallejo), or Sufi poets of ecstasy, or Basho …and toward the dry intellectual studies of human behaviour ( Drydan, Marvell, Ben Jonson, through to Hopkins and Clare and even Browning). In the U.S., if we speak in broad strokes, there was Whitman and Crane, perhaps above everyone else (and the Frost branch and the Cummings branch as borderline kitsch). And for all his ostentatious outpouring about Nature, I’d not consider Whitman a poet *of* nature. And many of these borderline branches became entwined by mid century. And they entwined at the University and its English departments. Lowell and Berryman, and Plath and ending with John Ashbery, I suppose. But something happened in a sense by the sixties, and its the same thing that happened to other art forms. And that is that too many people were making a career or art and career poets must teach to have a career. How many great poets are alive today? In english lets say. I’d say none. But I am very picky about poetry (I blame Ork for this). Bly is a great teacher and a very good poet. Not a great poet. A great translator, however. James Wright was close IMHO. Wallace Stevens and Theodor Roethke were both great and marked the last stage of modernism. But I don’t want to make lists here. Ondaatje’s Collected Works of Billy the Kid is a narrative poem of sorts. Its outstanding on many levels. But it is an expression, among other things, of the impossibility of writing as Dante once wrote, or Shakespeare, or Donne. Nor is it possible to write as Goethe did.

Yutaka Takanashi, photography.

Ondaatje is, in a sense, expressing something deeply nihilistic. The end of literacy. There will be post literacy literacy. Maybe there already is, and maybe that is why so few people even looked up from texting to roll their eyes when Dylan won the nobel prize. Now, the complexity of a certain kind of cultural death is possible to exhaust in any meaningful way here. But I hope I’ve been writing about it for the entirety of this blog’s life. But the point is that this shift toward man as an alienated being really took hold in the late 19th century, I think. The fuller version was the product of post WW2 U.S. culture as it was being manufactured on the spot.

The idea of this loss of Nature needs to be seen as a Western invention, if that’s what it is (or really it is the product of late Capitalism). And it is intriguing to sort of sample various side bar writing on the subject of nature’s intersection with the contemporary psyche as it is expressed in art.

“In“Anal-Erotic Character Traits” (1918), Jones locates a “primitive smearing impulse”

as the basis of all “molding and manipulating,” “painting and printing.”

And in “The Ontogenesis of the Interest in Money” (1914) Ferenczi sketches a

phylogenetic development of “copro-symbols”—whereby the child plays with

excrement, then mud, sand, and pebbles in a sequence of ever more pure materials…”

Hal Foster

Morris Louis

Richard Taylor wrote a sort of interesting if not terribly rigorous piece on fractals and Jackson Pollock..

http://oregonquarterly.com/the-curse-of-jackson-pollock-the-truth-behind-the-worlds-greatest-art-scandal

But this does touch on something significant about experience and art. And it brings me back to Berger. I think a lot of people are re-reading Berger now, after his recent death. And this can only be a good thing.

“In the 18th century, long-term imprisonment was approvingly defined as a punishment of”civic death”. Three centuries later, governments are imposing – by law, force, economic threats and their buzz – mass regimes of civic death.”

John Berger

Wesley Willis

Civic death includes the eradication of silence, too. While at the same time eliminating Nature. They go hand in hand. Of course the death driven morbidity of advanced Capitalist nations is trending toward a kind of silence, but it is the silence of stasis, of death and decay.

“One has only to think of the poems of Chaucer, Villon, Dante; in all of them Death, whom nobody can escape, is the surrogate for a generalized sense of uncertainty and menace in face of the future.

Modern history begins—at different moments in different places—with the principle of progress as both the aim and motor of history. This principle was born with the bourgeoisie as an ascendant class, and has been taken over by all modern theories of revolution. The twentieth-century struggle between capitalism and socialism is, at an ideological level, a fight about the content of progress. Today within the developed world the initiative of this struggle lies, at least temporarily, in the hands of capitalism which argues that socialism produces backwardness. In the underdeveloped world the “progress” of capitalism is discredited.”

John Berger

Adriaen van Ostade. (Lawyer in his Study, 1637).

Capitalism is the perfected distillation of all systems linked to *progress*. And the cultures of progress imply what Berger saw as point of view of expansion. Pre-industrial cultures were cyclical, and for peasants were focused on survival. But today expansion is being retrofitted for a *green* rebranding, and this is really the origin of this fixation on novelty and innovation. Innovation is not necessarily the engine of economic development, but it is the idea that serves as caretaker for the endless actual failures of economic development under capital. There not being, really, any free market the reaction was to find symbolic mechanisms to veil this fact. Airlines can’t survive without subsidies, but to talk about this means discussing all the ways Marx was right. Instead it is better to just write about innovative low cost airlines, or new luxury jumbo jets flying to high end resort destinations. In a sense this is just marketing. But on a wider societal level it is also *how* the world is seen.

The literal scope of the gaze looks forward expansively, while the survivalist culture narrows. Bentham invented the early panopticon control (Berger calls it accountancy in ethics) and this was followed on by schools, hospitals and factories. If the transition of peasant culture to the bourgeois societies of the West were best chronicled by the Dutch and Belgian painters of the 16th century — per Berger– it is intriguing to see Hals, or a Van Ostade as either the R. Crumbs of their age or the Oprahs. Van Ostade never seemed to tire of tavern settings, but perhaps these are the paintings of the society of non alienation, or non HYPER alienation. Dickens later chronicled the idea of meetings at the way station, the tavern or inn, too. This was the setting of allegorical fatalism. The road travelled by coach, the inn, the escape from the urban civic duties — for the bourgeoisie. Chance encounters. The uncanny stranger. By the 20th century travel was commodified and made into leisure. Escape was symbolic escape from work that imitated work. By the 21st century leisure imitated conquest and sadism, since there was really no work.

Shomei Tomatsu, photography.

The road of the 16th century through the early 19th was still a road without presumptions about progress. The industrial revolution set forth the new alienation (Haussman rebuilds Paris), and optical discoveries shift primacy to the eye, to details one cant see without optical instruments. Experts are born. The new priests of expertise on ‘techne’. But the self narration of our lives shifted when there was no longer an escape from commodified movement, and the greater digital panopticon. The loss of nature to the primacy of man that took place in poetry was seen in literature as well. Part of the psychological disintegration of the second half of the 20th century is connected to the loss of *place*, the sense of traditional custom, of a human scale in the face of Nature and of history. Kafka certainly wrote with a preternatural and prophetic insight about the coming insect age of the giant panopticon — the loss of silence is also, obviously,the loss of contemplative access.

The Utopian vision of 20th century architects was constantly failing, even in its most noble exercises. Brasilia was the gaze sent forward toward a widening future. But the progress imagined was cold and desolate and unnatural.

Palácio do Congresso Nacional. Brasília, 1960. Marcel Gautherot, photography.. Oscar Niemayer, architect.

The anal universe, for Freud (and Norman O. Brown and Marcuse) is the place before not only progress but sociability — it is the realm without limits. I can never look at Trump (who had gold curtains installed at the White House replacing Obama’s blood red choice) without thinking of his anality. That ‘golden showers’ became a meme is hardly surprising. But neither is it surprising that the U.S. ended up with Trump. His pseudo Versailles/Vegas taste is more revealing than his nativist rhetoric. And that both he and Berlusconi took to industrial level tanning sessions is plain disturbing. They exclaim, behold, it is my face of shit.

“…excrement is the most charged of symbols, a wild sign that the infant might take as a penis, a baby, a gift, money, and so on, all terms that are “ill-distinguished” and “interchangeable” in the anal zone. The anal-excremental, then, seems to oscillate between the physically literal and inert and the symbolically arbitrary and

volatile—a difficult oscillation psychologically. Moreover, in either register the anal zone suggests an indistinction that is also difficult to bear.”

Hal Foster

But I digress (slightly).

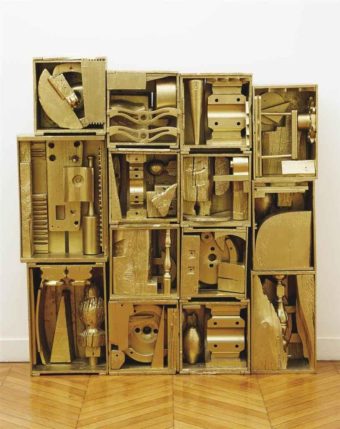

Louise Nevelson

“Consciousness reflects and does not reflect: what it

reflects is not what it seems to reflect, but something else, and that is what

analysis must disclose. Precisely because the activity that produced

ideologies was exceptional and specialized, they came out of social

practice – of everyday life – in two senses: it produced them and they

escaped from it, thus acquiring in the process an illusory meaning other

than their real content.”

Henri Lefebvre

Contemporary society has now begun to function as if there are no hidden layers to anything. Solutions are meant to be seen as total. Side effects are no threat to their completeness. As I’ve argued before, Abstract Expressionism was the last sincere expression of cosmic reach. The last Dionysian engagement. And hence it is the most acutely attacked. It is attacked from both right and left. From the right it is snickered at (Oh shit, give me a roller and some canvas and I’ll turn out a dozen Rothkos in one day) and from the left (Oh the CIA wanted to steer people away from real revolutionary art…meaning realism and mural painting etc). And since everyone is under the gaze of the Panopticon, nobody escapes.

Patrick Joust, photography.

“There is in the height of my fantasy, not an obcession but a thought that persists,

a fancy that psychoanalysis has found entertained by many children, of an other more

real mother than my mother.”

Robert Duncan

See Mere Virtual Presence (h/t J.L.) (http://server2.docfoc.us/uploads/Z2015/12/26/ktsVvyRlCQ/ceb55bcf2a596ab4a86c0cbc16dcc5c3.pdf)

The novel today only exists in any relevance in crime fiction. Intentionally minor and transient, there one can at least fine some kind of discovery. Ideas are avoided in much contemporary fiction and this is because ideas are avoided in the individuals own self narration. The journey has gone from Man before Nature, to Man as the only fit subject for study, to Subjectivity before an invented Nature (or generic mass produced Nature). The bourgeois educated class in the U.S. is acutely unaware of the rest of the world as a living collective of experiences. They operate within a vision that is no longer exactly about progress. It is no longer a gaze directed at that widening road ahead but rather a gaze directed at a screen with an image of a widening road.

“The visual arts have always existed within a certain preserve; originally this preserve was magical or sacred. But it was also physical: it was the place, the cave, the building, in which, or for which, the work was made. The experience of art, which at first was the experience of ritual, was set apart from the rest of life – precisely in order to be able to exercise power over it. Later the preserve of art became a social one. It entered the culture of the ruling class, whilst physically it was set apart and isolated in their palaces and houses. During all this history the authority of art was inseparable from the particular authority of the preserve.

What the modern means of reproduction have done is to destroy the authority of art and to remove it – or, rather, to remove its images which they reproduce – from any preserve. For the first time ever, images of art have become ephemeral, ubiquitous, insubstantial, available, valueless, free. They surround us in the same way as a language surrounds us. They have entered the mainstream of life over which they no longer, in themselves, have power.”

John Berger

Samantha French

The culture that today has normalized torture, while simultaneously inventing a history in which *we* don’t torture is the perfect example of this new empty self narrative. And of civic death. When Manadel Al-Jamadi died in custody and later had his body photographed on ice, battered and bruised, the description of his interrogator was ‘shabbily dressed overweight white man’. A CIA operative, but not a covert one. Al-Jamadi was alive, hooded, but walking under his power and coherent and answering questions when he entered the interrogation tier at Abu Ghraib. When he was untied (after being hung up, his hands tied behind his back) blood gushed from his mouth as if a faucet had been turned on. That was the description of witnesses. This murder is just one of many, but one that came to public attention. Except it didn’t really come to attention. Hollywood does not cast CIA ops with overweight unkempt white actors. The official narrative is one seen on screens. And the backdrop is artificial and manufactured.

This is all rather obvious. So the artists who painted animals on those cave walls were directly transcribing something of a Nature that surrounded them, and with relatively few filters. They did not gaze with the eyes of progress.

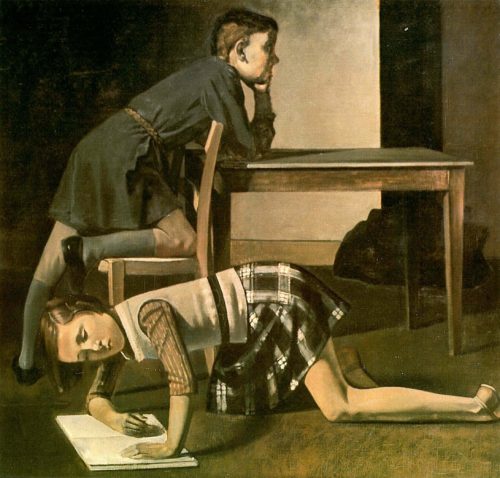

Balthus

Berger again…from Ways of Seeing, written in 1972:

“Publicity, situated in a future continually deferred, excludes the present and so eliminates all becoming, all development. Experience is impossible within it. All that happens, happens outside it.”

The paradox is that what happens, in art, does happen outside it. What is true, though, is that one can no longer experience it within the cultural panopticon.

The anal sadistic character of fascism was exhaustively explored by Pasolini and Genet, and a dozen others, and it is increasingly apparent in contemporary America. And in this sense Obama and Trump are flip sides of this same coin.

Steve Shaviro (oddly perhaps) wrote a nice short piece on Norman O. Brown a while back…

“The very idea of sublimation — moving from something “lower” to something “higher” — involves stunting the potentialities of the body, and setting up a hierarchy between mind and body, or even a total Cartesian separation of mind from body. For Brown, a radical desublimation is the only way to go: a return to the wisdom of the polymorphously perverse body, a rejection of goal-oriented culture in favor of living in the moment; an acceptance of death as part of life, instead of our dread of death which ironically turns life itself into a living death.”

The living death of the U.S. is found not only in super max prisons, or in a political class of zombie humans, from both parties..but it is found in the sexually desperate frat boy culture of VICE or the saccharine near autistic fairy tales from Hollywood…most of which are so depressing that the mind shuts down. Reading Norman O. Brown today, or Ernest Becker or Marcuse’s book on Freud, is to see that even they were under the spell of disenchantment. For them the polymorphously perverse body is still sort of imagined in a genital conception. It is still a bit too much like a Hefner playboy mansion orgy but with incense and taking place in a muddy field. Marcuse said, later, that we cannot imagine what a non repressed society would look like. And this is the truth of it. The desublimated self is probably closer to something like the silence of the desert, a coptic underground temple no longer in use, a cave perhaps.

Gary Fabian Miller

The contemporary culture of entertainment is not interested in those trompe l’oeil effects so popular with the producers of niche paintings in the mid 1600s. The birth of bourgeois collectibles, and patrons found something important in being momentarily fooled by an illusionist trick. Perhaps the best of those practioners was Gerrit Dou, a painter I find oddly but completely fascinating. And convincing. His later works in particular betray his early training in glass engraving and stained glass (his father manufactured stained glass) and then his apprenticeship with Rembrandt. And Rembrandt did not suffer the less talented. Dou’s portraits consistently teeter on illusion, as did all the Dutch *fine* painters of those decades. These were popular paintings, and bought by visitors to Holland, including royalty. Dou was in a sense the J.J. Abrams of early bourgeois society (European anyway). The difference is that Abrams and Hollywood overall today are not in the business of skillful illusion (by itself not an indictment) but rather are in the business of representing an illusion — and an obscuring of reality, not representing by way of an illusion a reflection of reality. Or…Dou was the early version of Thomas Kinkade. Take your pick. There is something in these (probably bogus) comparisons that touches on the general loss of a discriminating eye, and an ability to seek more. To soberly evaluate the emptiness of every gesture. The overriding dissatisfaction with one’s role.

“And in life itself, in everyday life, ancient gestures, rituals as old as

time itself, continue unchanged – except for the fact that this life has

been stripped of its beauty. Only the dust of words remains, dead

gestures. Because rituals and feelings, prayers and magic spells,

blessings, curses, have been detached from life, they have become

abstract and ‘inner’, to use the terminology of self-justification.

Convictions have become weaker, sacrifices shallower, less intense.

People cope -badly- with a smaller outlay. Pleasures have become

weaker and weaker. The only thing that has not diminished is the old

disquiet, that feeling of weakness, that foreboding. But what was

formerly a sense of disquiet has become worry, anguish. Religion,

ethics, metaphysics – these are merely the ‘spiritual’ and ‘inner’

festivals of human anguish, ways of channelling the black waters of

anxiety – and towards what abyss? “

Henri Lefebvre

The Mysteries Remain

Hilda Doolittle

The mysteries remain,

I keep the same

cycle of seed-time

and of sun and rain;

Demeter in the grass,

I multiply,

renew and bless

Bacchus in the vine;

I hold the law,

I keep the mysteries true,

the first of these

to name the living, dead;

I am the wine and bread.

I keep the law,

I hold the mysteries true,

I am the vine,

the branches, you

and you.

John, you are so funny–a perfect subject for a documentary

Violence of Silence is a symptom of Civic Death. Steppling’s essay Violence of Silence in one of this week’s Counterpunch editions, and Civic Death are two of the most profound essays I have read in a long time.

I don’t share the sentiment that the novel today only exists in any relevance in crime fiction. Philip Roth, one of my favorite novelists, has also lamented what he claims will soon be the death of the novel.

I think the perspectives expressed by Saul Bellow, and Woody Allen are closer to the truth about moving art, whether literature, cinema, or other forms. Bellow said that writers were asking a great deal of the reading public to put their faith in believing a writer had enough to say to make them want to spend the time it takes to read a novel, and that he was grateful that some very small percentage of the public believed he did. Allen’s sister in a wonderful documentary on his life said that Allen makes movies for himself, and a small audience who enjoyed them.

Of course Bellow also said he had the occasion to read the entire output of novelists in 1962 and he was bored silly, and, that despite there being no lack of talent among the writers he read that year, none produced an interesting, passionately absorbing novel. He also said that the 1920’s took the novel into an impossible blind alley, with the disintegration of language in Joyce, the extreme situation in Kafka, and the observance of non-art by Gertrude Stein.

While I have no prejudice against novels by John Barth, or Italo Calvino, I don’t appreciate their work in the same way I do free form jazz, even though I prefer the bop idiom with its more predictable melodic, and harmonic structures. Novels, it seems to me, in some respects need structure more than does free form jazz, or painting, and it seems more difficult to push established idioms to pieces with the written word, than with music. or painting, although the effect is the same in my opinion in pushing idioms, which is loss of profundity in some respects.

John Gardner, and Ayn Rand, both of whom wrote wonderful books on the art of fiction, made compelling cases that morality has to be at the center of the novel. Public, and private morality is so attenuated (hence the Silence of Violence); and the permanent states of distraction, and destruction of silence that Capitalism causes so pervasive, both states of which it thrives upon to push excessive consumption to medicate the incredible sense, (whether consciously acknowledged, or existing solely in one’s subconscious) that nags every human on the planet that surely there is more to life than what most experience, perhaps are conditions that have marginalized the novel more today than in the past, but artists, particularly the great ones, have always operated at the margins of society anyway.

The only work by Ondaatje that I haven’t read is his “Collected Works of Bill the Kid.” His prose is the most poetic of any novelist I have ever read. The only writer I’ve read who comes close to Ondaatje in producing a sense of beautiful surreal mysticism through the use of language is Paul Bowles. Ondaatje is not the first to note what he sees as an end of literacy, but forecasting the end of literacy is too pessimistic. It’s doubtful that societies before ours had any greater literacy of the kind to which he refers. We may have many more distractions bidding for our time, but there will always be a segment of the population that are diligent seekers of truth, and great literature is an indispensable search light for it.

Regarding silence, in general, and the lack thereof in cities in particular, I subscribe to the perspective on it of a late Buddhist monk of the Thai Forest Tradition named Ajhan Chah, who, in a wonderful collection of similes he used in Dhamma talks, said, “When you’re sitting in meditation and a sound comes in, it’s not the case that the sound is disturbing you. When that awareness arises, you’re disturbing the sound. That’s where you have to solve the problem.” Inner silence is what most people never cultivate; and neither true happiness, nor wisdom cannot exist without it, which is why there is so little of both today, and it can be found in a big city, just as it can in a secluded wilderness, although diligent mindfulness of the kind the Buddha taught is perhaps challenged a bit more in a city.