Julie Cockburn

“Every failure, a mysterious victory.”

Jorge Luis Borges

“To live in the world today is to live in a state of constant anxiety.”

Manfredo Tarfuri

“Plato likened philosophers to architects, because philosophers also provide

bases for all knowledge, although as was typical of the citizen of Athens, he

looked down on architects since in reality they are craftsmen.”

Kojin Karatani

There was a fascinating and oddly intriguing, if not compelling, short article in the N.Y.Times Style magazine a couple years back, on architects defending famously derided buildings. And for some reason this was connected in my brain with a brief piece somewhere, I forget, on the U.S. Navy’s new destroyer the USS Zumwalt (or the DDG 1000), a ship that seems to have cost billions and doesn’t yet work, and was described in the article as resembling a bit of failed Brutalist architecture. And it does resemble that, but therein lies something oddly and unconsciously disturbing. Never mind that each issue of a DDG 1000 would cost upwards of three billion, but also that they are already, apparently, obsolete. The style magazine piece, though, touched on several buildings I sort of love, as almost guilty pleasures. The Vela di Scampia, in Naples, which I’ve written of before (and famous as a location in the Italian TV crime drama Gomorrah) and the remarkable Tempelhof Airport terminal (now an historical site) in Berlin, picked by Norman Foster, and for once I agree with him; it is a remarkable building, and sadly one that will always be associated with the Nazis. It was also utilized as part of the set for Hunger Games (coincidence?). Annabelle Selldorf selected Harrison & Abramovitz’s Empire State Plaza in Albany. This brings up back, most directly anyway, to Brutalism. The Empire State Plaza is, at first glance, a monstrosity I suppose. Many think so anyway. Even I think so…mostly. But it is also an unsettling piece of architecture. And this leads me to an installation that Simon Terrell and the Assemble Collective created on the post WW2 Brutalist playgrounds of England. As one member of Assemble put it, the playgrounds were sort of condensed Brutalist sculptures. It is not too great a claim, I don’t think, to see the profound imprint of those playgrounds on English consciousness in the generations immediately after the war. It was both an expression of forced optimism, and a more unconscious sense of doubt, or even defeat. And yet, they were not completely either or any of those things. They were also enigmas. But they did provide the backdrop for the lives of countless children in the U.K. for some twenty years or so. There seems to be both a sort of fad, and genuine reappraisal of Brutalism going on right now. And often buildings are included for simply being made of concrete.

Alexandra Road Housing Estate, Neave Brown architect, built 1972-78.

The core Brutalist aesthetic is associated today with the former Communist satellite countries. And that’s not unfair, for countries like Bulgaria, and Moldova and Ukraine built thousands of concrete structures. Many were remarkable. So its important to tweeze out the anti-communist override, aesthetically, when looking at Brutalism. In England these buildings are associated with the post war welfare state, mostly. The Eastern communist structures were often partly sites of monument, while the English structures were utilitarian; often housing estates or bus and train stations. The Preston Road bus station remains a personal favorite of mine and its not insignificant that so many of these structures found their way into films. From Clockwork Orange to Get Carter to Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, et al; the landscape of psychopathology and crime was expressed architecturally by mid century Brutalism. But one thing connects brutalism whether its eastern Europe, South America, Russia or the U.K., and that is that this is an aesthetic that incorporates the poor.

Georgia Ministry of Highways, Chakhava and Jalaghania architects. Tbilisi. Built 1975.

Felix Salmon wrote, in The Guardian earlier this year:

“The international style evolved, and not well. What used to be aspirational started becoming an in-your-face statement of conspicuous consumption. The gauche gaudiness of was embraced not only where you might expect it (the Wynn towers of Las Vegas, say), but also in places with real history, such as New York City. Go to Columbus Circle today, for instance, and you’ll see Christian de Portzamparc’s billionaire condos at One57 face off against “a 1950s international style glass skyscraper in a 1980s gold lame party dress,” as Muschamp described the Trump International Hotel. Such erections generate almost as much hatred today as the worst mistakes of brutalism did in the 1960s, and understandably so: they represent a world in which the more obtrusive and ostentatious you are, the more profit you make.”

Ulrich Ruckriem

The revival of Brutalism (if that’s what it is) signals several things, I think. But the most important thing is that the best of mid century (and a bit after) Brutalism endures with a kind of integrity. It is resistant to gentrification, to some degree anyway, and it elicits dark memories of social unrest, and by extension of personal unrest and trauma. The best brutalist buildings are read as *traumatic*.

Jonathan Meades wrote…“There was good Brutalism and bad. But even the bad was done in earnest. It took itself seriously, which is a crime in The Market whose insistence is on mindless fun and moronic fun. Just look at television.”

Trump Tower, Las Vegas (Joel Bergman, architect). Courtesy of Dezeen.

There was a not so buried socialist vision attached to much of England’s post war building, and Erno Goldfinger (Fleming took the name for his Bond villain) who designed the notorious Trellick Towers, was a lifelong communist. But this is a less important aspect than the actual engagement with these buildings, certainly today. The Vela di Scampia, for example, was dead before it even had residents. Corruption, shoddy materials and almost zero infrastructure support relegated the housing estate to decay from the moment the project began. For it remains, if one steps back a bit, a singularly fine bit of architectural design. A haunting evocative and very human design. The point here, though, is how such work is read today. And if the very term *Brutalism* needs to be reconsidered. It is hard to lump Tadao Ando into the same basket with Marcel Breuer or Neave Brown or Goldfinger. And this is one of the key aspects to what evolved into Brutalism during the post war period; the use of concrete provides structures with a sense of place. The sand of Japan is not the clay of South America or Mexico, nor is it the red dirt of parts of the Eastern U.S. Concrete absorbs the local chemistry, it is an expression on some subliminal level of locality. And this is key to the sense of memory it instigates. It is a architecture of rejection and repression.

“The solicitations of theorists for a revision of formal

principles did not, however, lead to a real revolution of

meaning but, rather, to an acute crisis of values. In the

course of the nineteenth century, the new dimensions

presented by the problem of the industrial city made the

crisis only more acute, with the result that art was to

have difficulty in finding any suitable road by which to

follow the developments of urban reality. “

Manfredo Tarfuri

Mauricio Cattelan

There was a secondary interface, if that’s the word, between Brutalism and the city. Or the idea of the city as much as any actual city. Tarfuri felt that there could be no class based architecture, but only a class analysis of architecture (per Richard Ingersoll). As Tarfuri wrote, the question was how a building fit into society. And on a certain level, it is true that architecture gives concrete form to values and ideas. And to ideology. There is something in today’s prestige architectural stars that I find similar to the cult of Heidegger. A Zaha Hadid is the architectural equivalent of Heidegger. As Tarfuri said, these stars are infused with a kind of mysticism awaiting the final epiphany. Although this does a disservice to mysticism, I think. Hadid is really more like Zizek, in the end. Tarfuri was writing of Richard Meier, but one could add Philip Johnson to this list, from a previous generation. Kazys Varnelis observed of Reyner Baham…“suburbs floating free of cities are naturally suited to the expanse between the coasts. In the grand expanse of the American continent, the gridiron plan embodies the genius loci of the Jeffersonian land plat. Rather than obscuring landscape, the gridiron reveals it by drawing attention to changes in the terrain by following its contours.” And this is a bit like the post post modern theory of Zizek and Badiou, where there is no there there. There is only a free floating signifier, an intellectual suburb cut off from the human.

“Brutalism tries to face up to a mass production society, and drag a rough poetry out of the confused and powerful forces which are at work.”

Alison and Peter Smithson

Eugene Von Bruenchenhein, photography. 1940s.

The best of Brutalist building is defiantly located. And that is both why it attracts such derision, and also why it is undergoing such a revival. Piranesis, who Tarfuri quotes a good deal, saw the development of the urban centers of Capitalism as *absurd machines*. The southern California freeway system is really a sort of punctuation on Brutalism. As is the ubiquitous parking garage. In fact if one takes mass Hollywood entertainment as a gauge, the parking garage is the most recognizable architectural symbol of the 21st century. And it is both cemetery and site of violation. For nothing good happens in parking garages. People do not fall in love in parking garages, nor do they find revelation, satori, or peace. It is the distillation of all contemporary anxiety. This is highly relevant in seeing the growing but still mostly subconscious fixation on death in the post modern world. Mass media is flippant, in its political commentary, about a potential WW3. Oh that, pshhh. Who cares. And then you realize what is being talked about is the end of humankind. It is a kind of state beyond the cynical. This is the liminal spaces where suburb meets metropolis. When white flight happened, and the inner cities of the U.S. were abandoned by everyone but the poor, and mostly the black and latino poor, the reaction was the same smiley face numbness, the same snide snarky self congratulation. The ‘burbs were like the spaces on non-existence. Something was going on, or about to go on, but it was erased from consciousness.

Hitler loved his autobahn project. Anton Wagner, a German historian of sorts, wrote a book on Los Angeles in the 1930s and he saw this new sprawling city as a perfect model for the Nazi’s eastward expansion. Freeways, the engineering of mass movement, but individualized. And the perfect creation for enforced balkanization of classes. But this sense of death infects contemporary discourse as it is manufactured by a corporate system of electronic control. And this is the real meaning of freeways and parking garages, and of the isolated and hermetic faux populism (and not even that) of today’s *starchitects*.

Sarah Charlesworth

Within the suburbs of the U.S. today is a kind of lurking violence. The burbs are far more violent than any inner city. For this is the devitalized bourgeoisie that are the actual Trump base. The educated white bourgeoisie returned to the cities over the last couple decades and displaced the older inhabitants. Gentrification is a kind of revenge act. The architecture of the gentrifying class is one of decoration. It is presentation, and in that sense it resembles the same superficiality as most officially and institutionally validated artworks today. Taste is reduced and monetized. And the astute shopping instinct of the gentrifier is always at work fine tuning their property. They work on themselves (in the sense of therapy and aerobics et al) as they work on their lawns and hardwood floors. Even as renters, the idea is to differentiate themselves not from each other but from the blight of the burbs, and the memory of what they just altered. The bourgeois gentrification project is never about memory. All the overpriced heirloom artifacts only serves to dislocate these non functional objects of utility from their original purpose. Hanging an old shoe shine stand or wheel barrow on the wall, or repurpose it as a coffee table (on which to place a glossy art book on, oh, say Brutalism) renders the history nullified. It is like many museums, something too close to a mausoleum. The idea of taste is neutralized when it is expressed as a gesture of hierarchy. Gentrification is never anonymous.

But to return to the anxiety and rising tide of Capitalism’s death trip, this coincides with the new Victorianism, or Gilded Age of the U.S. Except that it is a Gilded Age of regression. The predication on expansion is a non starter, today.

Edificio Guaimbe, 1962. Mendes da Rocha & De Gennaro architects. Sao Paulo.

Alex MacLean, photography. (El Mirage, AZ.)

Great buildings are dreams. The syntax of architecture is not that simply of image. All architecture operates in a way much closer to a play or poem than to a painting or map or blueprint. And one of the seductive qualities of Brutalism is that it is so often haunting. The psychological space of great architecture is linked to that scenic theatrical space in which our narratives of self play out. It is as if all lobbies were ante-chambers to the primal scene. All basements were places of prohibition. And of course this brings up Bachelard, who perhaps better than anyone saw the poetic qualities of certain spaces. Benjamin did, too, of course.

“Standing there as a stage set for the event to take place, the work of architecture is praxis in itself; it informs and at times contests our subjectivity.”

Gevork Hartoonian

Children love to play in building sites, amid half finished structures, or in old abandoned buildings. I once had a job as a nightwatchman at a large Los Angeles medical center. I got the job, oddly enough, from a guy I met in jail. Figures he would turn out to own a private security company and he gave anyone a badge and uniform. Anyway, I worked the graveyard shift and had to walk through this empty eight story building punching my time clock; the old kind that needed a big metal key that hung on various walls in the building. I loved that job. Firstly, I was alone. But second, it was a magical place, a strange empty ghost riddled structure with a symphony of inexplicable sounds and in which one could drift off into various reveries. I mention this because it felt like childhood. Space can be evocative and, often, so frightening.

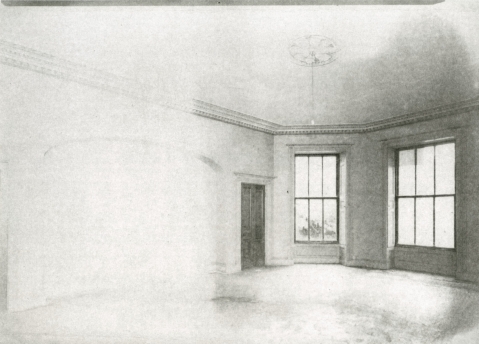

Alison Marchant, photography.

In the West, Tarfuri believed, the ideology of architecture changed after the financial crises of 1929. The new epoch was that of the *plan*. It was the hyper instrumental implementation of the desire for control of the future. It was a new architecture of capitalist inheritance. The sense that Roman law provided a substitute eternity in the form of inherited properties and wealth was becoming weaponized in a sense. Dominion over the serfs of the future.

“In order to survive, ideology had to negate itself as such, break its own crystallized forms, and throw itself entirely into the

“construction of the future.” This revision of ideology was thus a project for establishing the dominion of a realized ideology over the forms of development.”

Manfredo Tarfuri

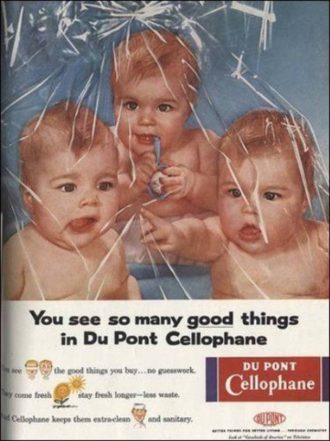

1950s magazine ad.

When George Simmel wrote of the city, in the 1920s, he emphasized the ‘indifference to value’ that seemed the core effect of monopoly capitalism. Eighty years later this has only worsened to a magnitude of a thousand. Tarfuri saw the extreme misery produced by Capitalism. But he also saw the extreme danger in being driven, both collectively and individually, by the belief in a progress founded on production and progress.

Detlef Mertins, writing on Walter Benjamin…

“…he nevertheless recognised that modernity

was not yet free of myth. Things produced as commodities under the

conditions of alienated labour were enveloped by false mythologies,

as evident in advertisements, fashion and architecture. “Capitalism,”

he noted in the Arcades project, “is a natural phenomenon with which

a new dream-sleep came over Europe, and in it, a reactivation of

mythic powers.” These myths, to which Georg Lukacs had

drawn attention to as being characteristic of the class consciousness of

the bourgeoisie, gave the world of reified commodities the appearance

and status of “nature” – a second nature that occluded the original

as it exploited it.”

Liu Wei

Benjamin keenly dissected the bourgeois dream, or delusion, of *progress* as it applied to architecture, and felt that the role of technology, of discoveries in building materials, ushered in, unintentionally, the residues of a kind of pre-history. That, for example, the new use of iron in the late 19th century provided structures that allowed for unprecedented views of the city below. And this relates to those optical technologies that developed during this same period, that ended with film, and which corresponded to the rise of psychoanalysis. There was suddenly both new details and a new visual macro perspective. For Benjamin, the close reading of the buildings of the past provided clues to the men and forces that built them, but also clues to the future. Looking at contemporary architecture, the face of advanced western Capital is the Trump Tower (any of them) but also it is the latent violence of the gentrifier, of the interiors of Park Avenue apartments and penthouses, and then finally, the strip malls and industrial parks that are scattered across the U.S. Nothing is to be found or read in the latest prestige architectural project of Norman Foster, or Herzog & de Meuron, or Aecom or Gensler or Renzo Piano or I.M. Pei. For none of these firms or architects are building from within a culture or even society. They are operative in a realm of exclusive wealth for patrons that have little interest in the equality of the future, or to in any ways lessen the suffering of those beneath the boot heel of the system that pays them.

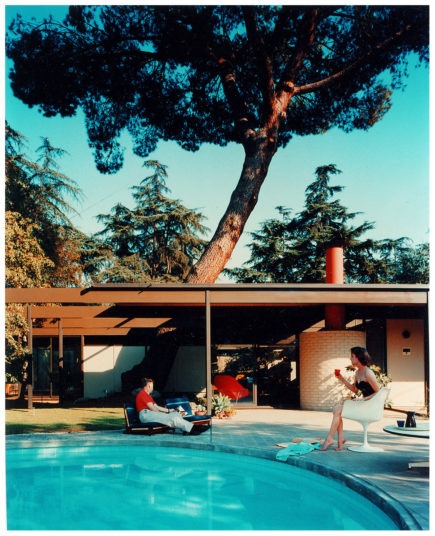

Julius Shulman, photography. Altadena 1958.

They build the architectural version of academic discourse, today. Structures that utilize private visual vocabularies, in a sense, that produce an effect of almost intentional purposelessness. They are buildings of futility, in one way, but of exclusion in another. And there is a huge topic in the relationship between photography and architecture, but without getting into that here, it is useful to quote photographer/artist Jeff Wall, on the buildings (especially interiors) of Mies Van de Rohe’s buildings…

“[These] buildings require an especially scrupulous level of maintenance. In more traditional spaces a little dirt and grime is not such a shocking contrast to the whole concept. It can even become patina, but these Miesian buildings resist patina as much as they can.”

The same could not be said of Louis Kahn’s brutalist complexes, or any of the great Brutalist housing tracts or apartment buildings. There is a very fine essay by David Campany (who is always just a revelation to read) called Architecture as Photography. He touches on a number of things, but his remarks on commercial and promotional photography is particularly relevant here.

“But nothing dates more acutely than high style. Like modish advertisements in old copies of Life magazine, Shulman’s photographs share the same aspiration as the designed worlds they represent and are subject to the same historical fate. Today such images do not so much promote as stand as documents of the taste and values of an era.”

Antonio Lopez Garcia

“Over centuries, architecture evolved symbolic languages that allowed buildings to declare their purpose, or at least codify it. Churches looked like churches, houses looked like houses, banks looked like banks and so on. However, with the beginnings of Modernism this began to be replaced by the idea that built form should follow function, along with a truth to the materials used. While this might imply a certain clarity or honesty, the modernising impulse also homogenises, tending towards rationalised modular forms that often cut the ties between function and legibility. This has been felt equally in the ‘high’ architecture of prestige buildings and the ‘low’ architecture of social housing and the factory.”

David Campany

The visual grammar of the Industrial revolution, and after, is one that developed certain clues to be read as *rationality* (Campany noted the absence of shadows as a signifier for scientific neutrality) and which found later style codes in everything from fashion to political presentation. The electoral arena of U.S. politics, and really Europe, too, was one in which those cues became a kind of eraser. No shadow, for example, became emotional suppression. The bourgeoisie quieted down until today the vocal discourse of the haute bourgeoisie is barely audible. Which is fine because they don’t want to be heard, really. The men in the grey flannel suits that occupied the corridors of power were looking to erase humanness and vitality. Erase sexual energy. Except of course it must come out somewhere, and so it does, in displaced aggressions against those that have what they feel they must deny. Violence against blacks and homosexuals and most acutely, women, is not just a product of economic self interest, for a system that must perpetuate various repressions, but also one of emotional resentments. Widespread use of SSRIs is a form of self muting. Capitalism is now almost always in *airplane mode*; it is inaccessible and moving toward silence. From Beckett to Marco Tirelli, the movement is a dialectical one that addresses silence as either end game or liberation. And it teeters between the two.

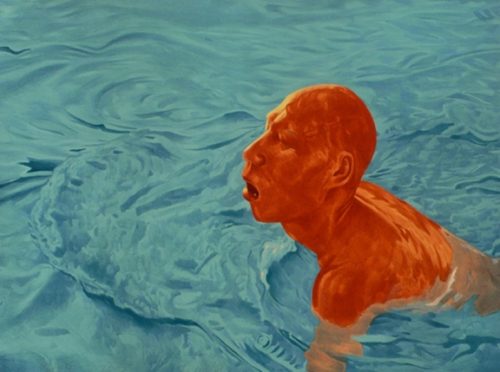

Fang Lijun

“The right to property is always a right against other people. Thus, property establishes relations of superiority and inferiority, the customs and

sentiments that surround it provide many of the most fundamental elements in our social order.”

Brian Elliot

The industrial city of the 19th century was predicated upon work. The impact of factories impacted the populace. And this marked the start of *housing* — dwellings that housed workers. These were sites of control, not freedom. Education became an institution of monitoring rather than anything else. Same with public health institutions. The point here is that the amnesia of the U.S. today extends to notions of the places people live and work. The mythology of individuality is one that demands constant forgetting. Tract homes and areas where condo development strips apart the landscape, must replace what is gone with a new pre-fab version. Usually this is a new kitsch pastoral (think of the names of most housing developments). The hidden or stealth cues often harken back to an imaginary of pioneer ingenuity or rugged individualism. To the westward expansion as a rite of God given privilege. But its not ever seen quite as privilege, but as something *won*. Americans love nothing more than the idea of a wager. And they like even better a rigged game. And in a sense Trump is the unconscious expression of that desire — that he is a cheat and economic predator is seen as a good thing. So across all this is a new blindness to the irrationality of the modern urban landscape. And a learned insensitivity to the actual spaces in which one lives and works. Those big ticket architects build to erase the surrounding landscape.

Phillip Govedare

Where once the unconscious dynamic included a control of the future, I think that has given way to both a panicked present, the anxiety of keeping what one has, and this creeping morbidity. A morbidity that is expresses the accumulated repressed material of the death drive. The post apocalyptic narrative is now so familiar as to be expected. Hollywood churns out endless variations on the theme of reconstruction.

“Today in Britain (and in America, and perhaps most western

countries) the movement towards a more authoritarian state is

accelerating. In this country, the failure of successive governments to

restore the nation to anything like economic health produces

circumstances of grotesque inequality and much disillusionment with

the existing major party machines. In an atmosphere of despair some

turn to neo- or crypto-fascist ideas, believing that blacks and Jews can

be blamed for our ills and urging upon what seem like increasingly

sympathetic governments the need for stronger central control: water

cannon for the police, an expanded role for the army, more powers of

surveillance, tougher immigration laws to keep out the foreigners.”

Brian Elliot

The bourgeoisie today in the West know the dangers of massive militarization, but those dangers don’t scare them as much as the anxiety of the status quo they fight so hard to maintain. This is the cognitive dissonance of the liberal in Western society today. The battle to keep what causes you unbearable angst is resulting in olympian levels of repressed material returning and producing unimaginable levels of hysteria.

Alexandra Road Housing Estate. Yes, that is really amazing. It’s haunted me since the first time I saw it 14 years ago. I was on a night bus at around 3am. It was cold and there was a bit of freezing fog. The bus went past this estate and I just couldn’t take my eyes off it. It pulled at the back of my mind. It was shocking for me. Just so oddly beautiful. I’m not from Britain, and yet the estate managed to evoke some sort of historical memory within me. I have no words for it.