Monique Mouton

“I see photography as a very classical medium, with of course all kind of genres—portrait, abstract, science photography, and so on. What I am also interested in right now is the negative, since it seems that it is going to disappear soon. When I ask my nine-year-old daughter, “What’s a negative?” she can’t say, as she knows only digital photography.”

Thomas Ruff (interview Apeture)

“The modern world develops a technology increasingly alienated from

everyday experience. This is an effect of capitalism that restricts control of

design to a small dominant class and its technical servants. The alienation

has the advantage of opening up vast new territories for exploitation and

invention, but there is a corresponding loss of wisdom in the application

of technological power.”

Andrew Feenberg

“When Freud seeks to explain the process of dreaming, he is not content simply to explain to the reader the often offensive reality of the latent, or hidden, content of the dream, as opposed to its superficial, manifest con- tent. He also feels bound to explain to us that the process of dreaming itself connects us to our primeval past. As he explains it, when in the process of dreaming, we move from the sophisticated realm of conscious language to the unconscious realm of the dream-image constituted by primitive percep- tion, we re-trace the steps that humanity took in the course of its long evolu- tion. Even in the dream, which is surely the most symbolic realm described by Freud, there is the link to the animal and indeed the reptile within.”

John Desmond

“In error only is there life; and knowledge must be death.”

Friederich Schiller

There is a nice short essay at Aeon, which serves as a nice concise debunking of the ‘brain as a computer’ model that has gained such popularity. https://aeon.co/essays/your-brain-does-not-process-information-and-it-is-not-a-computer

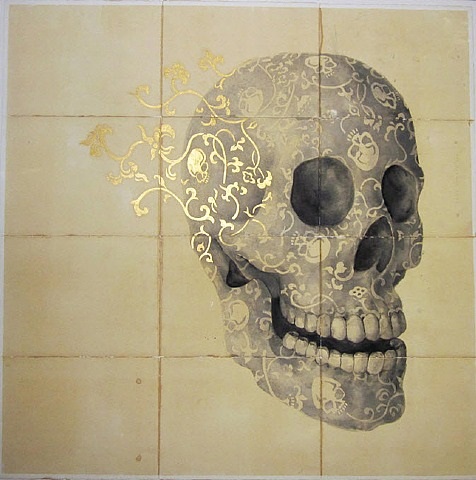

Agus Suwage

And it has a lot of implications culturally. Some of those implications are obvious, but others are very far reaching and not at all obvious. When Siegfried Kracauer wrote that the essence of cinema was in its photographic nature, he was suggesting that cinema was realistic, but for Kracauer, the idea of realism is highly elusive. Benjamin was in a sense the one who extended Kracauer’s ideas by implying that the photograph was capturing something previously (usually) unseen, or rather that as Constance Penley writes…

“…the realism that photography claims as its privileged realm cannot be conceived as an immediately graspable physical presence or the recorded data of common sense. Rather the ‘realism’ of the photographic image is exactly one which opens out onto a different register of epistemological relations, one in which the idea of the unconscious must be taken into account.”

The brain-as-computer model has clear ideological roles to play. For one of the conceits of computer science is the exactitude of computer reasoning — that everything can be eventually understood by computation. Edgar Morin, whose work is still not fully translated into English, begins his best known work (on education) by saying “Education should show that there is no learning which is not to some extent vulnerable to error and illusion.” The idea of the infallible is baked into ideas associated with realism. And alongside that idea is one of that privileges the idea of *common sense*. So there is an apparent paradox at the center of this. But its mostly illusory. The cyber world of virtual reality and algorithmic predictions and so forth is both realistic and unrealistic. In a sense the unrealistic is treated realistically.

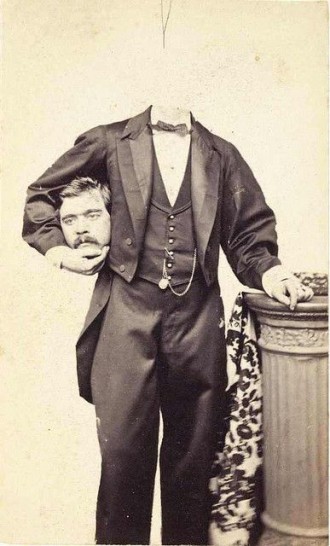

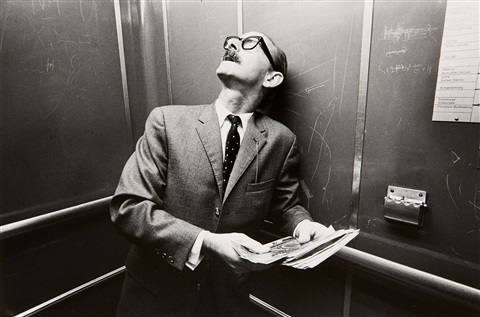

“The Headless Magician” unknown photographer. Date unknown.

I think there is an assumption –at least in the U.S. — that emotion clouds judgement. The neutral emotionless robot (Dr.Spock again, from Star Trek, not the baby doctor) is very appealing to the geek culture.

“Affectivity may stifle knowledge, but it may also enrich it. Intelligence and affectivity are closely related: the ability to reason can be diminished or destroyed by an emotional deficit, and impaired ability to react emotionally may cause irrational behavior. “

Edgar Morin

Wesley Tongson

(As a completely arbitrary sidebar here, Morin along with Jean Rouche made a documentary film in 1961 called Chronicle of Summer. This was a film that hugely influenced Godard. I’ve not ever seen it and in fact it has always seemed rather hard to find although I think Criterion has an issue out now. Anyway, it took on the mantle of *first* cinema verite feature. Which, considering the growth of reality TV and the like makes it an interesting cultural item and one also directly related to Algerian independence and later May 68 ).

The allure of artificial intelligence — that particular meme, is one that has very little to actually do with perfecting intelligence in ourselves or creating machines that think, and maybe think better than us. It has more to do with repressed sexual feelings, as George Zarkadakis has noted, there is a long history of stories about humans creating some form of machine or automaton that one cannot tell from other humans and then lusting after it. And that, says Zarkadakis, suggests the real drive behind about AI is erotic.

Of course Margaret Boden, back in the 70s, wrote…“By “artificial intelligence” I therefore mean the use of computer programs and programming techniques to cast light on the principles of intelligence in general and human thought in particular. In other words, I use the expression as a generic term to cover all machine research that is somehow relevant to human knowledge and psychology, irrespective of the declared motivation of the particular programmer concerned.” Which is actually pretty remote from Kubrick’s HAL or android overlords.

The fascination with *touching* inert matter and making it breathe is something that exists in human allegorical thought since cavemen. Shamanistic cults and ancient civilizations dream, always, at some point, about that border region between life and death. Life and after life. I don’t really believe anyone, deep down, thinks that human intelligence can be duplicated in a computer. I DO think that many in that AI world believe that machines can come to be self operated and semi autonomous, and maybe even something like ‘self aware’. And I think they believe that AI can be hugely more efficient than humans. And better than humans perhaps because they can’t be human. And that begs the question, as always, with what is meant by efficient. And this strange flight from our own humanness. People get answers wrong but do not cease to be people, nor even stigmatized as useless people (well, not often) for mistakes. And so here there is this confluence of factors; the notion of efficiency, the idea of quantifying working ability and hence intelligence of some sort, and then the ways in which this theory begins to shape emotional life and create values. Making mistakes is, in fact, increasingly seen as a larger failure than it once was. The desire for control becomes more and more eroticized. But conversely, in a sense, the quest for AI machines and this investment of desire is partly an outgrowth of a patriarchal regime that senses it is dying. The nuclear family and jealousy and the punishing Father all find expression in android fantasies. The terrific BBC series Humans really captured a good deal of this ambivalence. Most Hollywood science fiction presents androids as very appealing, as more attractive than humans.

ALWAC III, 1959. Irma Lewis, NWRC programmer at console.

“Tradition was overthrown in modern times and society exposed to the full consequences

of rapid and unrestrained technical advance, with both good and bad results.

The good results were celebrated as progress, while the unintended and

undesirable consequences of technology were ignored as long as it was possible

to isolate and suppress the victims and their complaints. The dissipated

and deferred feedback from technical activity, such unfortunate side effects

as pollution and the deskilling of industrial work, were dismissed as the price

of progress. The illusion of technique became the dominant ideology.”

Andrew Feenberg

The ideological aspect of instrumentalized thought is partly expressed in the ruling class assuming a position akin to God. The presumption is that of being outside, or, really, above the process of progress. The ownership class tacitly acts as if there is nothing they do not or cannot ‘see’. And this delusion of independence trickles down to infect even daily discourse in the West. All the new Utopian thinking, if that is what it is (more on that below) is couched in terms like post human and awash in bioengineered downloaded virtual subjectivity. The subjective is now conflated with the technical, and vice versa, and that technical in play here is one that still ideologically manufactured by the ruling classes.

Thomas Ruff, photography (photograms).

The idea of realism is linked to a world view in which class segregation is normalized and technology is the province of common sense, but a highly specialized common sense. That specialization results in a sort of new priest class of techo expert, but an expert in specialized and highly detailed common sense.

And running alongside this new expertise, in these seminaries of trans-humanness, is a manufactured urgency. For technology is now inseparable from the clock. Technology is of the moment. Innovation is old before it is conceived almost. In application it is most certainly old. And this youthful priest class of technician, the novitiates of this downloaded subjectivity, view the world as if the world does not really affect them. THEY affect the world, or the presentation of a world, but they are immunized against the very values and conditioning they implement. But maybe more, they don’t quite feel as if they are part of the world.

“The image of life versus mechanism reappears constantly in the critique of social rationality, not just in relation to technology

but also markets and bureaucracies that appear metaphorically as social machines. This image culminates in the dystopian literature and

philosophy of the twentieth century.”

Andrew Feenberg

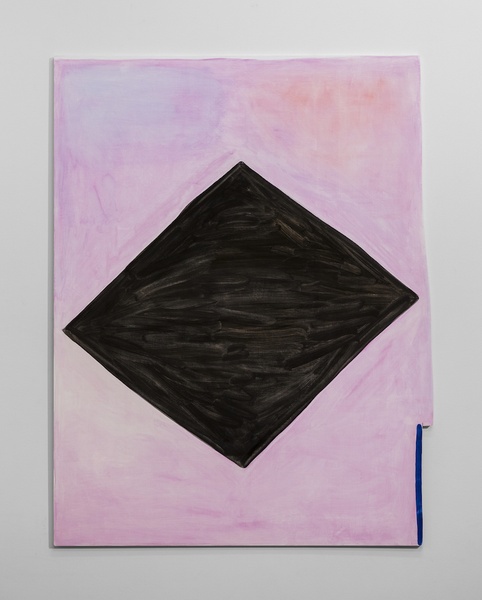

Serge Alain Nitegeka

Cutting across questions of technology is, of course, the market. Capitalism creates commodities and commodities are in principle exclusionary and encourage maximum alienation. Commodities are also, almost always, standardized. So nothing that exists under Capitalism is neutral. Bias is built into everything. And if the internet (and related technologies) are (in the parlance of studies on post humaness) ‘de-worlding’, this bifurcating of consciousness is also mediated by the logic of Capital. And the logic of Capital, and of the Capitalist — the ownership class — is one of optimization. And the consciousness that interacts in the institutional sphere is one that finds it ever more convenient to just ignore human side effects or casualties. Now in many cases the capitalist class has internalized (and often eroticized) this act of ignoring to the degree that it becomes an aspect of their overall desire. There is an addictive erotic component to sort of wishing away huge chunks of the world. I think much of the *overpopulation* argument is indirectly linked to this. It is an only partly suppressed wish. All institutions take on the metaphoric qualities of machines. Everything is a network and the imagery tends to employ circuitry and wiring etc. And I think a part of the attraction of that model is in the way humanity is marginalized. The spin is always about this great concern for humanity, but in fact the cyber realm is free of this very messy human dimension.

“… such high cultural formations of modern societies as science, philosophy or elaborate theological doctrines should not be regarded as belief-systems. I have no doubt that there can be good reasons for treating them as such and that it is possible to offer an appropriate de nition of the concept which would allow us to do so. However, given the explication just presented, they do not qualify for several reasons, the most important being that they are disembedded from the context of other social practices: their criteria of primary validation are internal to them. “

Gyorgy Markus

The development of digital communication, the internet and electronic media of all kinds has served to erect this post human notion of the de-worlded as if there really were no people involved. The desire to lose one’s humanness seems very advanced in the West, now. Machines don’t dream, after all. (do they?). And some of this is a product of the fact that computers do not engage the material world. They can affect the material world, but not directly. There are no crafts people in computer science. There is no feeling per se. The worker at the keyboard is making use of a repository of components and data and resources that immaterial. Computer technology is pushing a boundary however (to contradict Heidegger), it’s just that it is pushing in the opposite direction. Rather than revealing the essence of any particular object it is retreating as far from that essence as possible. So far that it runs up against a kind of limit or reverse boundary. And this limit is intensely difficult to identify and describe because it is something that feels nihilistic. I’ve noticed a lot of Hollywood TV and film lately in which characters return from the dead. There is something in the Zeitgeist that feels already dead. Either that or it’s just further infantile narcissism.

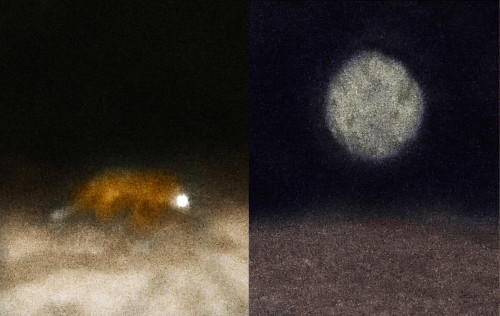

Contantin Schlachter , photography.

One of the roles of art is to mediate dreaming and to stimulate latent material, repressed desires, but also to encourage a kind of self awareness. And this inches into a discussion of what *culture* means. For now, the question regards technology, or rather computer technology and artificial intelligence, is that science has catalogued and appraised the material world — from one perspective anyway — but it has indeed exhaustively researched the geological and biological world. The question is to what degree is this researched and catalogued research and study shaped by the system in which it is operating? In other words that drive for control and domination that fuels Capitalism (and this to some degree includes the Enlightenment) informs our language, our discourse, our relationships with other people and our unconscious. We dream Capitalist movies. Even putting aside aspects of ideology for the sake of a thought experiment here; the technology of contemporary life is one that distances the subject ever further from a primordial relation with the world (and people). And using that word, *world* carries its own baggage. One could as easily say Nature. But implicit in all this is an ‘idea’ of totality, of ‘a’ totality. And the very use of scientific grammar (biology etc) serves to demonstrate the primacy of instrumental logic. The totality must be tamed and made to submit. And computer technology and information science is, in the view of those who create these systems, perfectly suited to manage the unruly planetary population.

“Thus the paradigm selects and determines conceptualization and logical operations. It designates the fundamental categories of intelligibility and controls their use. Individuals know, think, and act according to interiorized culturally inscribed paradigms. { } The paradigm is both underground and sovereign in all theories,

doctrines, and ideologies. The paradigm is unconscious but it irrigates and controls conscious thought, making it also Super-conscious,

In short, the paradigm institutes primordial relations that formaxioms, determine concepts, command discourse and/or theories. It

organizes their organization and generates their generation or regeneration. The “great Western paradigm,” formulated by Descartes and imposed by developments in European history since the 17th century, should be mentioned here. The Cartesian paradigm disconnects subject and object, each in its own sphere: philosophy and reflective research

here, science and objective research there. “

Edgar Morin

Lukas Duwenhogger

Again, it is useful to remember that Capitalism cuts across this paradigm as well as being an intrinsic part of it. Classes are created for the ruling class to appropriate value. Capitalists are always in the process of doing this.

“…the whole point of Netflix is to deliver theatrical illusions to you, so this is just another layer of theatrical illusion—more power to them. That’s them being a good presenter. What’s a theater without a barker on the street? That’s what it is, and that’s fine. But it does contribute, at a macro level, to this overall atmosphere of accepting the algorithms as doing a lot more than they do. In the case of Netflix, the recommendation engine is serving to distract you from the fact that there’s not much choice anyway.”

Jason Lanier

Human domination is always going to be mystified. That is part of the role of Capital in all this. But even putting aside the economic aspect of AI and computer technology in general, there are deeper issues that have both an aesthetic and political dimension. And Wittgenstein is very a useful place to start this discussion.

“A perspicuous representation produces just that understanding which consists in seeing connections.”

Ludwig Wittgenstein

Luiz Zerbini

The short version is that nothing is context free. And for Wittgenstein there are always similarities that cannot be defined. We *recognize* them, but we do not *know* what they are.

“The problem here arises which could be expressed by the question: “Is it possible for a

machine to think?” …. And the trouble which is expressed in this question is not really that

we don’t yet know a machine which could do the job. The question is not analogous to that which someone might have asked a hundred years ago: “Can a machine liquefy a gas?”

The trouble is rather that the sentence “A machine thinks (perceives, wishes)”: seems somehow nonsensical. It is as though we had asked “Has the number three a colour?”

Wittgenstein from the Blue and Brown Books

And this touches on something only indirectly related but something I find hugely important. And that is that such questions as ‘can machines think’ are not really questions. It is not that different from people who ask those semi rhetorical questions that are only possible for people in certain positions of privilege (What can we do? What is to be done then? etc etc etc). And it is not a question as Gerald Casey points out, because it has no range of appropriate answers or responses. As Wittgenstein said, too, “…we can talk of artificial feet, but not of artificial pains in the feet.” The important part of this discussion is what does it mean to *think*. And there is no remotely simple answer for that. All psychological verbs are problematic in the end. Part of the genius of Wittgenstein was that he grasped the illusions embedded in language and grammar. And such illusions are both ideological, and ontological. I know what you mean when during a conversation you say something like ‘I’ve often thought that’. I know the function of that sentence in context. But this is the ‘pointing’ element Wittgenstein addresses. That sentence points me toward what you meant. And the meaning, that is a whole other discussion as well. I can say I know what you mean, but this indicates only a social agreed upon usage — I might know you had previously thought Chocolate Chip ice cream used to be better. I had previous experience of your tastes. But the issue remains. And this is a good example of the reductive nature of discourse today. And that science and info tech tend, always, toward a reduction-toward-function. If it works, if it can be coded, then great. Good enough.

Ulderico Fabbri

Adorno’s critique of Heidegger (and Jaspers et al) sees the subtle validation of what he called ‘the declining elite’ and in a sensibility that later takes (in one form) the instrumental logic of obscurantist techno jargon associated with AI and post humanness.

“Those philosophers like Hegel and Kierkegaard,

who testified to the unhappy state of consciousness for

itself, understood inwardness in line with Protestant

tradition : essentially as negation of the subject, as

repentance. The inheritors who, by sleight of hand,

changed unhappy consciousness into a happy non-dialectic

one, preserve only the limited self-righteousness

which Hegel sensed a hundred years before

fascism. They cleanse inwardness of that element

which contains its truth, by eliminating self-reflection,

in which the ego becomes transparent to itself as a

piece of the world. Instead, the ego posits itself as

higher than the world and becomes subjected to the

world precisely because of this.”

Adorno

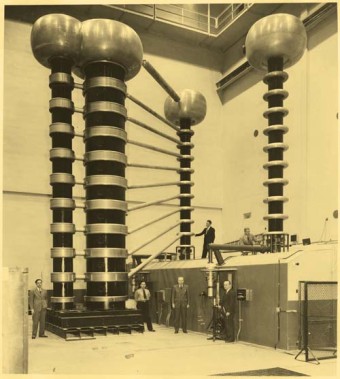

Testing 1.4 million volt X Ray machine. 1941.

Human inwardness is directed to think of itself as higher than the world. An identification with the Capitalist class, in other words. This has resulted in a kind of new age subjectivity in which the ideal is a kind of emptiness, but an emptiness amenable to marketing nonetheless. Or, in other words, the inward is treated as an object of outwardness. The objectified empty subjective. When Adorno notes that the Heideggarian subjective (inward) is one that satisfies the need for contact — the shared sense of authenticity — this ends up very close to the National Socialist volkish community, it is then not a stretch to see the AI community (and I mean this is an extended sense) as much the same. It is almost an inverted volk mythology. Retreat from actual political (and for that matter, cultural) knowledge is compensated by a surplus of empty opinion. And this is marked in much of the new faux-left whose anti communist feelings are perfectly predictable. The rejection today of psychoanalysis (of Freud in particular) is equally predictable as part of the unconscious aligning with substitute Patriarchs. The new AI and information technologists tend toward a solipsistic set of talking points, but also their own cyber-volkish jingoism.

The aesthetics of this mystifying is noted in work that is jargon free — and image that resists jargon, for that is equally pertinent. The visual corollary of jargon. As Wittgenstein noted, some similarities cannot be known. Why two paintings which are not hugely dissimilar can seem widely different in quality is a process of discernment which is today ridiculed by the regime of *common sense*. And part of this ridicule always privileges technical virtuosity over all. And here one returns to those ideas of *realism* with which we started. For that term, in fact, is mostly meaningless. Realism, work that accepts that label, is work of domesticated representations of a vetted worldview. Just as an aside, it is shockingly easy, actually, to walk into a gallery and determine very quickly if the work has any value. This is not 100% the case, but it is certainly usually the case. There are certain visual cues to triviality. Even work I don’t personally respond to I can recognize in it a certain seriousness — or lack thereof. Today, the bureaucratization of language is laced with tones of mystical contemporaneity. Everything is, remember, on the clock.

Noburi Takayama

The rise of AI theory (and to a large degree the entire transhumanism or post humanism movement) over the last thirty years, and really, more, over the last fifteen, has more to do with ideology than it has to do with technology. The science geeks will scoff at such an idea, but interest in machines (or inanimate objects) that take on human characteristics, or come to life, goes back to antiquity almost. The uncanny marionette and doll narratives were replaced by machines, but infrequently. It took the development of post industrial technology, and really, computers, to return interest to this fantasy. The rise of the internet has certainly changed daily life in significant ways, but it also hasn’t changed it in many ways. It has not revolutionized human consciousness. But the entire thrust of AI runs along parallel lines with ANT theory, and Autonomist Marxism and the like, none of which I find very useful. And all of which it seems to be just kicks the can further down the road. The appeal of disciplines of distraction is easy enough to understand, and mirror the new wave of anarchist thinking in political discourse. Information Technology was directly critiqued by Bernard Stiegler, who is perhaps the one interesting post Marxist (maybe because he is actually so Marxist)…but I probably just like him because he served time for armed robbery.

Peter Benson wrote about Stiegler and Baudrillard, and said…

“Baudrillard also noted how in contemporary society “the drive for appropriation and satisfaction… is supposed to be the deepest of human motivations.” In Political Economy of the Sign he contrasts this with the views proposed by Freud in the early Twentieth Century, who “advanced the exploration of human psychology immensely, taking such minutiae [only] as his starting point. But the fantastic perspectives this revealed have scarcely ruffled the composure of… economic ‘science’” – including, needless to say, Marxist economics. Baudrillard is disputing the Marxist perspective in which humans are defined by ‘needs’ which can be ‘satisfied’. Most ‘needs’, Baudrillard contended, are created artificially by advertising through a process which short-circuits the intricate complexities of desire as glimpsed by Freud. But robotic responses are more socially useful than reflection. In much contemporary psychological research, technologies for creating consumers’ needs and satisfactions have replaced the patient delving of psychoanalytic thought. Furthermore, many modern psychological theories view the brain as a collection of modules devoted to efficient information processing – essentially no different from a computer. As the central character in Richard Linklater’s recent film Boyhood (2014) remarks: “Robots are taking over the world. Not because machines are running everything, but because people are being turned into robots.” { } Stiegler distinguishes ‘information’ (including, for example, the accumulating data we can find on the Internet) from ‘knowledge’. “Knowledge and understanding must be psychically assimilated and made one’s own (one’s own self), while information is merchandise made to be consumed – and is therefore ‘disposable’. Knowledge individuates and transforms the learner, interiorizing the history of individual and collective transformations… The information diffused by the programming industries disindividuates its consumer”. In this way our Information Society takes a quite different shape from the Industrial Societies of Marx’s day, yet is even more corrosive of humanity.”

J. Bennett Fitts, photography (driving range).

And here is Stiegler in an interview from 2011:

“Later, after the French Revolution and the Industrial Revolution, you had the organization of the public sphere, of the lay sphere, of teaching and public

education, etcetera. And it was always agreed upon that it was impossible to submit this activity to the economy. But in 1979 in Great Britain, Ms. Thatcher said: now we will submit all these things to the economy. And at the same moment Reagan did the same in America. And after that Mitterand in his way, in social democracy. But everybody did in fact, the

whole world did the same. Even in Soviet and Chinese society. { } But my problem is not to qualify the traits of the state; it is to qualify the goals of the state. What is a strong state? At the moment here in France there is a proposal for privatizing the police. And you might know for instance that there is also a project, I think in Germany, for privatizing

the military, like in America. The Iraq war was already a war fought with private armies. It is a return to the situation of the seventeenth century, to the age of mercenaries. Now, are we talking about the state here? When you say that the state is very strong, what if the state is only one man, for example Sarkozy or Berlusconi, who gives money to a privatized police? Is that really a state? No, it is mafia. The mafia is very strong, not the state. What is the state? Here I have a problem with Derrida, Deleuze, Foucault, and all those French philosophers, who are always criticizing the state.”

And this relates again to the ideology of information technology. And the reductionism at work in information technology and computer logic. Those unknown similarities of Wittgenstein are just pushed aside. They don’t matter. Everything is treated as bulk material to be distilled down (a false distillation, in fact) to simple deterritorialized vacancy.

Heinrich Riebesehl, photography.

The notions of photographic realism that Kracaur and Benjamin spoke about remains a very salient topic. For the early 20th century was still in optical thrall to the industrial revolution. Representations of reality were predicated upon the vision of an expanding productive Capitalism, on the idea of progress, and expansion and with that, colonialism and finally control. The destabilizing images of Atget or Sander were subverting these assumed visual perspectives. After WW2, and really, this was also taking place after WW1, there was a shift toward another worldview — a sort of post industrial capitalist Utopia. Progress, or some part of it, had arrived. And this was being challenged by modernist artists; everyone from Rothko to Neruda to Celan and Burroughs. To Genet and later Pinter and today, in the financialized capitalist regime, of globalized neo-liberalism, the resisting image is found — if we take photography say, in work that deeply inward looking and quiet — in meditative pictures that are working to fill that artificial emptiness of Heideggarian Being. Awoiska Van der Molen, Rut Bree Luxembourg and Sam Laughlin and Frederike Von Rauch, or even in someone such as Thomas Ruff whose work is less meditative perhaps but whose vision looks to disassemble a prevailing notion of post modernity. There are countless others I could mention. Or an artist such as Marco Tirelli, or Toba Khedoori, or Victor Man and Mircea Suciu. Again, there are dozens of others. One of Stiegler’s insights (that I think was taken to some degree from Leroi Gourhan, one of Stiegler’s favorites) is that human consciousness evolved in connection with technics (sic), meaning only that early man, those cave painters, were discovering themselves by mimetic activity. And language came out of this and alphabets as well. As Stiegler has it, man is marked by indeterminacy, incompletion, nonclosedness (sic) and this is really the cost of being human. And humans are social or they are not human, finally. And that is the feeling of urban life in the West today; the escape from our own humanity, a desire for a sense of protected isolation and anonymity. And the internet is a perfect tool for luxuriating in anonymity.

Szymon Oltarzewski

There is within information technology and its operations an inevitable reduction, a return to basic equivalences, to exchange value as an eternal form. The self of the transhuman epoch finds consolation in the compulsive repetition of self naming and the circulation of that naming act. There is no sub-text, no substratum, only the concept endlessly repeated or referenced. The internet’s promise remains, as does the promise of all technology no matter how mediated by the motives of profit, no matter the conditions of its creation or manufacture. The promise is the same promise the painters of Lascaux felt picking up a piece of charcoal. The control system of the U.S. and to a slightly lesser degree the U.K. is one in which the anxiety of experiencing these endless loops is increasingly treated with anti depressants and various other psychotropic drugs. The statistics are breathtaking as the sheer numbers of people taking medication for psychological conditions is staggering and the trend is now to medicate younger and younger patients. But the problem with Stiegler’s thinking is that while he perceives the programming of an entire population, and the effects of electronic multi tasking and the strategies of distraction, he also overvalues the transformative potential of technology. This echoes the late Marcuse and runs into the same problems. The analysis is insightful, but the solutions offered are specious. There is also a sort of fatalistic pseudo Utopian aspect at work here; the new information systems of the large telecoms and internet providers, from Google to Facebook and Microsoft and all the rest, are not really changing anything except the nature of the symptoms. These symptoms are escalated and intensified, to be sure, but the condition of human consciousness remains relatively unchanged. Or rather, the historical conditions change and those shape us, but technology is itself only a social symptom. What Reich called ‘the emotional plague’ isn’t changed by the advent of computers. Poverty and surveillance, police brutality and a constant incitement to violence as the best action in problem solving, and class war, all exist outside the sphere of technology. Most mass media depicts basic fictions and not reality as most people experience it. The corporate owned media obscures reality. So in a sense the public today is more prone to delusional thinking that at any time in history. And their delusions contain the manufactured desires of media and marketing, and the internet and social media is the ideal technology to express obsessive compulsive behavior. But the basic neurotic structure of people’s psychic make-up is largely the same I think.

Mariam Medvedeva, photography.

“Consciousness plays a relatively incidental role in his {Freud’s} scheme. Just as we become aware of the external world by representing its objects through perception, so consciousness acts as a spectator who tries to make sense of unconscious mental processes. It is thus not difficult to understand why we can exaggerate the extent of our conscious autonomy and misperceive our agency in formulating the goals and attitudes we take to be products of our own volition.”

John Desmond

Our idea of the self is really just a background setting for our awareness of the world. The hegemonic marketing apparatus enforces various models for desire and sexuality. All of them are finally un-gratifying and this endless experience of mild disappointment is the constant of post modern society. The self is a fiction most people recognize but find easier to ignore. For to resist these mechanisms of control requires what is perceived as simply unimaginable effort. This is the dullness effect of the hyper super ego that resides over contemporary humans.

Curtis White quoted Jacob Bronowski…..

“I have a great many friends who are passionately in love with digital computers. They are really heartbroken at the thought that men are not digital computers … And that seems very strange to me.”

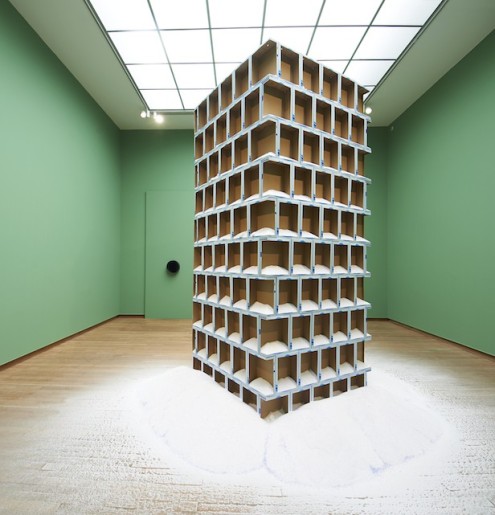

Navid Nuur (installation at Bonnefanten, Museum Maastricht, 2013)

Retreat from the public sphere, such as it is, is utterly understandable. The technology business, the ascension of robot workers and automatization of almost all semi skilled labor, as well as the extreme polarizing of wealth today has meant that a culture of hyper solicitation, as someone said and I can’t remember who at the moment, encourages — intentionally or not — a society building their own psychic prisons. Or a better metaphor is their psychic panic rooms. Mental isolation chambers where one can more comfortably sink into the repetitive infinite of eventual death. For there is an unmistakable nihilistic aspect to AI enthusiasts and information scientists and technology engineers. For whatever reason when I hear ‘artificial intelligence’ I think of cryogenics. For me its on the same continuum.

“The kingdom of God cometh not with observation: neither shall they say, Lo here! or, lo there!” for it is within and everywhere.”

(Luke 17 : 20)

Speak Your Mind