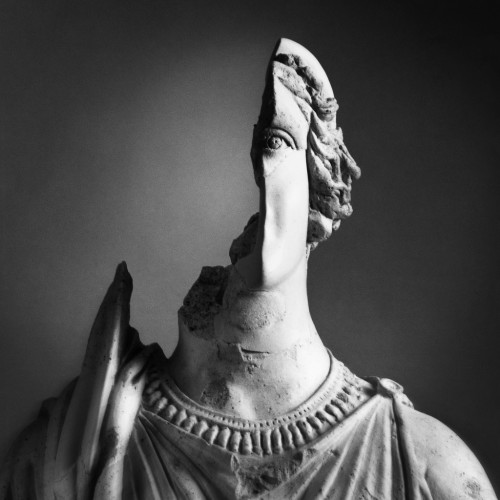

Mimmo Jodice, photography.

“All work is a crime.”

Herman Schuurman (1924)

“Teaching is not a lost art, but the regard for it is a lost tradition.”

Jacques Barzun

“Art is the tree of life…science is the tree of death.”

William Blake

Jacques Barzun wrote a sort of fascinating small book titled The Use and Abuse of Art (echoing Nietzsche). It is interesting not least because of its clarity. Like Kenneth Clark, Barzun is terribly out of fashion. And yes, he’s pretty conservative, too. But he is also a deeply perceptive observer of culture, at times. At the beginning of the book he writes, in light of Schiller’s book on poetics…

“What does Schiller tell us? First, that modern man is is split — or as we should say in modern jargon, alienated. Being divided, feeling not at home in the world, he is unhappy, self conscious. He is always examining his impulses and goals, always as we say, in two minds about them.”

Barzun goes on to suggest that this self doubt, this anxiety, really, results in people thinking more instrumentally, and becoming less spontaneous and more calculated. Now this is sort of interesting, being written in 1974 (or rather spoken because this is from a series of lectures). But the point is that this is of course far too simplistic. And yet its not exactly wrong. Now Barzun is usually lumped into the same basket as Lionel Trilling (they worked together as editors of the Great Books series) and perhaps Irving Howe and Edmund Wilson. The far idiotic end, or rather the bottom of that basket (to keep my metaphors straight) one finds Alan Bloom or later Harold Bloom. These were the mid century popular public intellectuals. And today I suspect they are missed far more than anyone wants to admit (well, not Harold Bloom…but he came later and it is telling that he was of another generation). Russell Jacoby wrote…

“The history of rhetoric illuminates the issue of public intellectuals.

Classical thinkers studied and valued rhetoric, in large part, because

public life depended on oratory. In Rome, public speaking was a preeminent

civil occupation. “No pursuit,” wrote Cicero in “On the

Orator,” “has ever flourished with greater vigour than public speaking….almost

every ambitious young man felt he ought to bestir himself

to the best of his ability to become eloquent.”

Jon Bailey, photography. (Chichen Iza).

Barzun was writing to be read. And not just by specialists. This seems a rather quaint idea today, but the loss of writing-to-be-read happened, also, because of and along with the de-politicizing of public life. Politics became electoral strategies or mere gossip. And that loss drained something crucial from cultural life as well. And saying that he wrote to be read is too glib a comment. And it also smacks a little too much of an anti-intellectualism that always lurks in cultural life in the U.S. But what Barzun valued was the idea of the critic. Nothing more, really, in that context.

It is too easy, as I’ve said before, to fall into the conservative complaint about education. Its a simplistic argument because one cannot separate education from the role of commodification and advertising and financialization. There is also the role of computers and the internet. And that is so vast a subject that I think often it is just avoided because the implications are so vast. As Jacoby says, the problem is not an illiberal education and the loss of liberal values, but an illiberal society. A society that professionalizes labor — that commodifies everything and that has more fully embraced a utilitarianism of risk management. So when Barzun writes of art and religion, he is writing of that evolution from Raphael and Durer, Shakespeare and Dante and Rembrandt and Mozart, to a conflicted or contested Kantian notion of Nature and the spontaneous. And it is an historical fulcrum in a sense. For this was a shift toward something that came to be associated with *genius* and bourgeois individuality. It was not until the mid 1700s that the term *aesthetics* even began to be used, and this corresponds to the first European museum.

Ding Qiao

Still, the Greeks saw nothing odd in similes about artists and Olympus, that artistic creation had spiritual value. Barzun glides over this fact in a kind of cynical elision that sees the rise of art’s autonomy corresponding to the erosion of religious conviction without mentioning an evolution in social relations and the rise of a new class of burgher. But none of that is really my point. For what seems more interesting is the insistence (by Barzun and others) that primitive man (sic) made totems or painted on cave walls in some sort of religious ritual. And that following upon that came a specific intent of artists in relation to organized religious tenants. And I simply don’t think its that easy or simple. Firstly, whatever those distant humans of thirty thousand years ago might have meant by their red hand prints or their complex perspectival depictions of animals, it was most certainly more multi purpose than just ritual.

Art is never one thing. It is an expression of multiple things. Barzun argues that not until the start of the 19th century were artists seen as prophets or seers, and that this then transferred the weight of interpretation toward the individual. And I think this is mostly true. But again, there is something in this reductive time line that omits too much (even if we’re just talking western art and culture). Barzun argues (and Edward Casey did the same) that God withdrew from eternity and was rediscovered in man and Nature. Well, ok, sort of…except that this begs the question about what is meant by *Nature*. However, what Barzun IS right about is that the shamanistic aspect of the artist is linked to magic. Except we better define magic. (below).

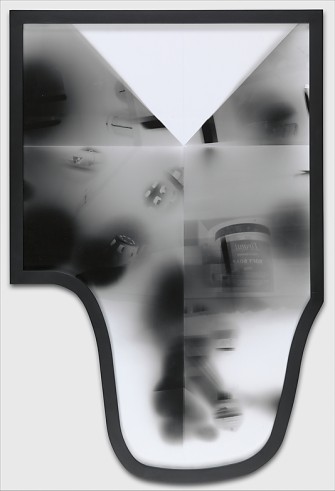

Dierk Schmidt

Rozsika Parker and Griselda Pollock argued that the term and idea of *artist* grew out of the post Enlightenment climate in which artisans strove to achieve social status on a par with the ruling classes. And Monika Parrinder writes…“…graphic design is increasingly encroaching upon the thought processes and spaces once designated for art, and its practitioners are calling themselves artists. This is bound up with the desire, over the past twenty years, to earn for graphic design the status of a “legitimate” discipline, a liberal art alongside respected fields such as architecture. “ There are countless versions of the basic time line version that ended with the cult of genius. Larry Shiner saw the introduction of sympathy or empathy in the 17th century changing the definitions of *expression*. And while that’s true, to a point, the problem is again that it implies an absence of this idea in, say, Dante or Shakespeare. Or Hesiod or the Vedic poets. So, it is more accurate to see these interpretive changes as reflections of social conditions (and here we return to Barzun on the alienated man, which is, as he defines it, connected directly to industrialization and exchange value). For the artist or artisan, or whatever one wants to call those mysterious people who painted horses on cave walls, they were all connected at some level by their psychic formation. And that formation is, indeed, socially mediated — to a huge degree– but that mediation is itself is shaped by language and human relations. In other words, the psychoanalytical truth of our self narrative certainly changes but it is always a dialectical dynamic with history. And this is exactly why the greatest failing of cultural criticism is to be reductive. For history is always alive. Which I think is a paraphrase of Faulkner.

“Judgment rested with the patron, in the age of the artisan. In the age of the professional, it rested with the critic, a professionalized aesthete or intellectual. In the age of the genius, which was also the age of avant-gardes, of tremendous experimental energy across the arts, it largely rested with artists themselves. “Every great and original writer,” Wordsworth said, “must himself create the taste by which he is to be relished.” But now we have come to the age of the customer, who perforce is always right.”

William Deresiewicz

Michael Wolf, photography.

“What is internal to the person is claimed as the realm of freedom: the person as a member of the realm of Reason or of God (as “Christian,” as “thing in itself,” as intelligible being) is free. Meanwhile, the whole “external world,” the person as member of the natural realm or, as the case may be, of a world of concupiscence which has fallen away from God (as “man,” as “appearance”), becomes a place of unfreedom.”

Herbert Marcuse

In any event, today the overriding illusion is that of choice. Jonathan Crary suggested the same when speaking of what he called ‘the global regime of self regulation’. The shift toward this bourgeois idea of *genius* accompanied in its later incarnations (in the U.S. primarily) by notions of expertise in shopping. The expert had become the expert shopper. Artworks were commodities and hence evaluated according to the market. The contemporary expert is one employing the latest algorithmic calculations in order to bid smartly at the next Christie’s auction.

The always insightful Sven Lutticken wrote…

“Boredom is a modern concept. Just as people had gay sex before modern notions of homosexuality were around, this does of course not mean that premodern people never experienced states that we would now characterize as boredom. Rather, it means that boredom “in the modern sense that combines an existential and a temporal connotation” only become a theoretical concept and a problem in the late 18th century—in fact, the English term boredom emerged precisely in that moment, under the combined impact of the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution.”

Getulio Alviani

And this is a linkage with this idea of bourgeois individualism again. Just as is adolescence a modern concept. But there is something menacing about ideas such as boredom because it raises questions of repetition and obsessive compulsive behavior. And maybe that sounds paradoxical, but it should only do so for a second. The sedimented accumulative history of repression and Oedipal terror looms — the societal coercion that demands labor measurements, the exploitation of labor time and the reinforcement of punishment as a precondition for order and stability, all this reacts against even the implied humorous side of what Lutticken writes.

And Lutticken adds….“Today’s academia is marked by a drive for quantification and control; immaterial labor needs to become measurable. The increasing integration of art in the academic system, with the rise of artistic PhD programs, is another example of this.”

Joshua Simon (by way of David Harvey)…..“The collapse of the Soviet Bloc saw the fall of the economy of productive labor and the rise of asset and commodity markets. The “trickle-down” economy promised by Reagan, Bush, and later Clinton, did not result in renewed investment in production, but rather in assets: the stock exchange, real estate, and the art markets booms.”

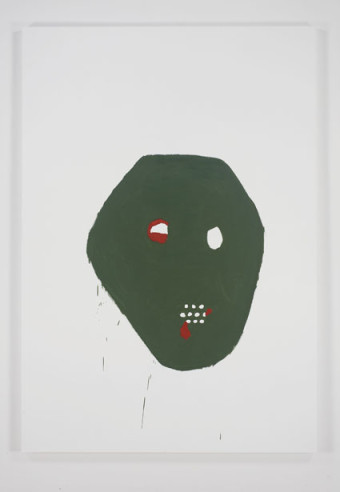

Thiago-Martins-de-Melo

I am reminded of Jonathan Beller’s ideas here, that the rise of the internet signals a global incorporation of the senses by the economic. The production of subjectivity is linked to a reorganization of social relations, then linked to image circulation and the atrophying of the word and text. And while I think this is basically true, I’m not at all sure of the furthest implications of it. Marazzi called this the ‘privatizing of the general intellect’. Franco Berardi Bifo writes…“Our main political task must be handled with the conceptual tools of psychotherapy, and the language of poetry—much more than the language of politics and the conceptual tools of modern political science.” And this strikes me as correct and I think the societal forces in Europe and the U.S. are subjugating all consciousness in an effort to control research and technological development. Intellectual labor is geared toward war. Well, war and domestic control systems. But the loss of empathy is the byproduct of these efforts (or the main one) and the loss of language and narrative means that huge numbers of students in University systems are struggling to articulate to themselves the crisis before them. In fact everyone is.

Adorno thought that the real shift, culturally, happened before the Enlightenment. What Zuidervaart called the ‘time of patriarchal myths’. When nomadism was replaced by Hellenic or Judaic societies. The time of religion. And for Adorno this meant the task at hand was to de-mythologize these early deifications (per Zuidervaart) of man. These myths however have to be seen as partly an expression of interior development, psychic development in the individual, while also containing ideological mandates (patriarchal primarily). For Adorno, the de-mythologizing was a form of reconciliation. This was Adorno’s anti Hegelianism. The negation of a negation was not an affirmation. The reason this is relevant here is that today’s society of advanced capital, colonized or subjugated by this global regime of financialized risk management and self regulation, is one in which only a radical reconciliation of man and nature can begin a social transformation. But this really means a rescue of the non-identical. And there is only a scant residue of the non-identical today — for that is the actual outcome of this production of subjectivity — this privatizing of the general intellect. The difficulty, as Adorno saw it, was that the promise of the non-identical is not kept, and in fact this breaking of the promise of Utopian dreams is almost a de-facto product of the desire for it. This is a huge source of misery of contemporary society.

“Since identity thinking ranges over the natural world as well as the cultural one, the breaks—or hints of breaks—in its application are the general condition for the appearance of beauty.”

Nikolaus Fogle

Taisuke Mohri

The draining of subjectivity has transformed the tragic into the trivial. Freud, in Mourning and Melancholia wrote…

“An object choice, an attachment of the libido to a particular person, had at one time existed; then, owing to real slight or disappointment […] the object relationship was shattered […] Henceforth the shadow of the object fell upon the ego and the latter could be judged as if it were an object, the forsaken object.”

Tom Allen quoted that in a short essay on Adorno and I think it’s very telling. This is disenchantment. But it is also disenchantment by way of perpetuating the mythology of the Enlightenment, and more, of Capital. For that shift Adorno referred to was profound in that our entire language participated in this spurious individuation. The global regime of self regulation is the global regime of reification and alienation. Looking back at Barzun’s essay it is clear that his somewhat arbitrary linear progression conceals more than it reveals. For in many ways today, the misery of daily life feels much closer to Shakespeare than to Pynchon. And I suspect this wasn’t true a mere thirty years ago.

Seung Woo Back, photography and media.

“Stendhal’s dictum of art as the promesse du bonheur says that art thanks existence by accentuating what in existence prefigures utopia. This is a diminishing resource, since existence increasingly mirrors only itself. Consequently art is ever less able to mirror existence. Because any happiness that one might take from or find in what exists is false, a mere substitute, art has to break its promise in order to keep it.”

Adorno

This is a famous quote of Adorno’s, and a controversial one. The germane issue here, though, is what is meant by happiness. The idea of promise is simply potential — awakening. For this is intimately linked with the fact of suffering. For what does it mean to imagine under a regime of erasure? Adorno is actually profoundly optimistic in the sense that he embraces the facticity of suffering — of misery and looks to a transformation that can only occur if the untruth of a society weighted down with its own contradictions and authoritarianism is no longer denied. The false hope of cheap cultural bromides is the greatest enemy of liberation. The contemporary world of mass media and entertainment; from VICE and the pseudo left of Salvage or Roar, to the sleazy caricatures of drama that Hollywood manufactures are the constant cheapening mechanism of deceit. For the non identical is that which resists the conditions of its creation. But art (more on that definition below) is that which fails by way of its attempt, of its desire, and through that failure creates a space or moment of resistance — for the non identical is resistance, it is a refusal of consensus with the status quo. Adorno feared the morality of custom, and saw in it the conformity of authoritarian society — the coercive need for social agreement where principle gives way to group think, and in this is the narcissism and projection of a fallen state, a lost language of empathy and concern.

Elizabeth McAlpine, photography.

In a late lecture Adorno speaks of the right life, or right living that cannot exist in a wrong society. It is a remarkably dense sentence, actually. But the idea is explored at some length in his posthumously published lectures on Moral Philosophy. Because its not just the false society, but the false person cannot live other than falsely under such conditions. So the artist is the final recourse to resistance — at least on one level. Praxis or social action cannot but be counterproductive if this is not at least acknowledged. Art must both resist simple duplication of Nature, and yet not rely entirely on its own artificiality. And the problem is, as he states in that quote, existence increasingly mirrors only itself. And in the regime of total reification and image and narrative colonization, the mirror is actually broken (to stretch a metaphor). This is why excessive popularity is so dangerous. The artist must sensitize him or herself to the siren song of approval — yet never actually reject it. And it may well be in this realm of diminishing returns on Nature free of generalized privitization that the shelf life of artistic expression is increasingly short. One must create (and think, philosophically) that which is non conceptual. The artwork that finds such interstices psychically, is also precarious in its nearness to repetition and death.

Jacques Barzun

The cheap mystical or intentionally obscure and new age is only a return to the identical — to a reductive conceptualizing of the status quo seen in the light of kitsch spirituality. And this is the exceedingly difficult aspect of art today. For the co-opting of image and the degrading of language means that the tendency – reflexively – is to reproduce the same, the identical. To reproduce the very conditions of domination under which one suffers. Art is not complaint. It is never narcissism. And this is, again, increasingly difficult. And this is why the reactionary demand for empirical rigor is so insidious. For theses salves are comforting. And this is why Lukacs, for example, is so full of shit about his classical heritage or unity of representations of man (and why so many leftists still harbor these regressive but comforting cliches). For in fact, it is (to paraphrase Adorno) not what the words say that matters, but what they mean — what the image mimetically induces. It is not conceptual nor is irrational per se.

James Gordon Finlayson’s excellent essay on this subject in Adorno expresses it best…

“Recall that as we have told the story so far, works of art promise happiness because they actually embody a certain organic harmony between part and

whole, which suggests a certain relation between individual and society that is denied to individuals in the present social world and provides a vivid point of contrast to it. Artworks thus transcend the existing world, with its principle of functionalization, and its economic and administrative domination, just as they transcend the whole associated cognitive and ideological apparatus that according to Adorno serves and perpetuates those institutions…. By virtue of the harmony realized in their aesthetic form, artworks bring to light the absence of harmony in the world picture social world. But Adorno flatly denies this. “

Renata Boero

It is why, to use a trite example, the abstract painting that includes a small representational image, is almost always kitsch and sentimental. Abstraction doesn’t mean abstracting Nature, it means something expressed outside of nature. Or as Adorno has it…speaking of Greek sculpture: “The unity of the universal and the particular contrived by classicism was already beyond the reach of Attic art, let alone later centuries. This is why classical sculptures stare with those empty eyes that alarm – archaically – instead of radiating that noble simplicity and quiet grandeur projected onto them by eighteenth-century sentimentalism.”

I have said before, ’embrace failure’. And usually this has been understood as an apologia for not making tons of money writing summer blockbusters. But here we are in 2016 and the encroachment of a surplus unconscious (which is a term Beller used first, I think) is occupying that space that once served only simple repression. The repetitive quality of daily life, down to and maybe most intensely, each minute by minute lived in the Necropolis, allows less and less elasticity in mimetic engagement. The Death drive of compulsive repetition is acutely present in the propaganda of mass culture, and the titillations of gratuitous violence and pornographic objectification of life. But most of all in the incessant soliciting of opinion about the identical, about the same. The hyper solicitous imposition of surplus image and demand to feel need, the manufactured desire of marketing projects. The tacit knowledge that these images and words are disposable then wears down the mental space of reflection until none is left. We dream commodities. We want, sometimes desperately, that which we know will bring no satisfaction.

Geert Goiris, photography.

“Art works of the highest rank are distinguished from the others not through their

success—for in what have they succeeded?—but through the manner of their

failure.”

Adorno

There is a clear sort of relationship between mass electronic culture and all its marketing campaigns, and giant telecom product including social media and the idea or ideal of art. But today the sense of psychic fatigue is so great, the loss of mimetic expansiveness so acute, that there has been an increasing complicity between audience and the social body. In other words audiences in the West, across the board, search for agreement. The Walking Dead or Breaking Bad become social grammar. And yet, amid this colonizing there occur odd almost accidental fragments that undercut these images and metaphors and stories. And it is a mistake to not see this. And yet I am not convinced, finally, that a particular episode of The Americans, say, transcends its context and the conditions of its production, not fully. Still, it’s wrong, I suspect, to discount such negations, either.

The more damaging corner of today’s culture resides within University programs for the arts. I wrote of this before, the virus of MFA programs. And I also have found that those involved will dig their heels far deeper than the crass hucksters of Hollywood. The ernest politically correct liberal bromides of MFA theatre programs — coupled to the ersatz avante garde imitations are, both, defended with enormous energy. And it seems obvious that these programs then turn out many of those same Hollywood hucksters. The ones that remain behind are the worst offenders, finally. The not quite tenured artistic janitors for institutional exclusion. And such is the desperation for cultural meaning they will often become shrill and strident in their defense of a system that has largely stopped their own career and artistic trajectory. Cultural Stockholm’s syndrome. Or maybe Munchausens.

There is another dimension at work in defining *happiness*. And this is now discussed in terms of ‘enjoyment’, and this is linked overtly with economic return. Tragedy can’t be sold the same way rom-coms are sold.

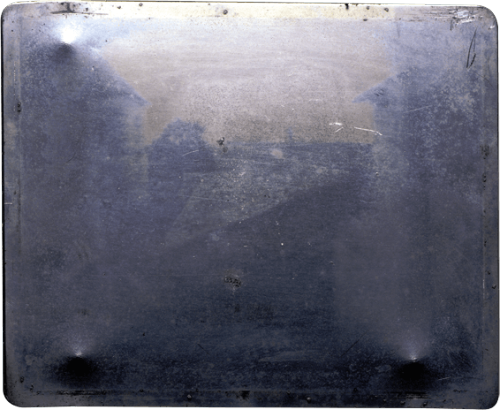

First known photograph, Nicéphore Niépce, 1827.(Heliography. Window at Le Gras).

Happiness and enjoyment are vague words in cultural terms. Or in artistic terms. For gratification is often delayed or even withheld. And some of this is mediated by, again, the sheer amount of image and story and product. Everything is sampling everything else. One might *enjoy* Game of Thrones, but that is not the same register of enjoyment one gets watching a production of Sarah Kane’s 4;48 Pyschosis. One does not quite know how to *like* Kane’s play, not the way one *likes* your sister’s posting of kitten pics on facebook, or your Uncle’s new Toyota, or a cheeseburger. What does any of this mean, finally? And sexual pleasure is so mediated under advanced capital that I often suspect everyone is at least partially sado/masochistic in a clinical sense. Pleasure is not always release. It is contemplation of that withheld release, often. But the conditioning today with respect to authority is very extensive.

“…we are faced with a dilemma. If we try to derive the authority

of morality from some natural source of power, it will

evaporate in our hands. If we try to derive it from some supposedly

normative consideration, such as gratitude or contract, we

must in turn explain why that consideration is normative, or where

its authority comes from. Either its authority comes from morality,

in which case we have argued in a circle, or it comes from something

else, in which case the question arises again, and we are

faced with an infinite regress.”

Christine Korsgaard

It is, in other words, very hard to tweeze apart what morality means in the context of a dominated society. But there are also changes in how people see and hear. Roger Stahl has mentioned the soundtrack that came with the Iraq War courtesy of the state department and Hollywood. The war was presented like a music video, in fact. And this leads into questions of happiness and certainly pleasure, and aesthetic pleasure.

Luca Andreoni, photography.

“In 2003 a new word was introduced into the English

language: Militainment. We now consume war in much the same way we

consume any other mode of entertainment. This has become a prominent

feature of American life in the 20th Century. The blending of war an entertainment

is not necessarily a new phenomenon. What is new is the massive collaboration

between the Pentagon and the entertainment industries. In addition, the scope of

militainment has grown rapidly. The television war has now invaded popular

culture on multiple fronts including sports, toys, video games, film, reality TV and

more. How has war taken its place as a form of entertainment? The answer to

this question has powerful implications for who we are and the world we inhabit.

Join me as we map the terrain of this new entertaining war. This is Militainment,Inc.”

Roger Stahl

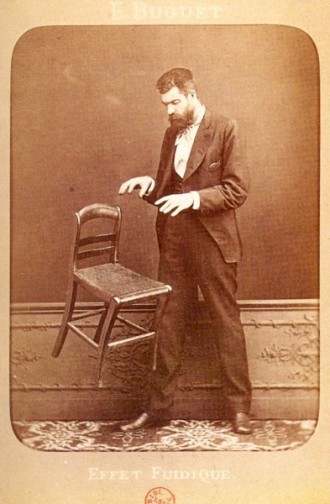

Magician’s Card, apprx. 1910.

Now, to return to Barzun and this idea of public intellectuals. In one sense I think it is a huge loss but in another, the absence of what is traditionally seen as a public intellectual, is no loss at all. For perhaps this idea of public is now so eroded and deformed as to be meaningless. By which I mean, the world, or the Western world, is a virtual public. One cannot argue this I don’t think. Prospect magazine listed what they believed were the world’s (sic) leading public intellectuals. The results were predictably horrifying. The list included…Steven Pinker, Slavoj Zizek, Richard Dawkins, Paul Krugman, Jared Diamond, Niall Ferguson, and Elon Musk. Of course this is a conservative publication, but then only conservatives would even entertain this idea. And lists are famously idiotic anyway. Still, it suggests something about the loss of a certain kind of thinking. Dominic Losurdo or Carlo Ginzburg or Roberto Callaso are not mentioned in the top one hundred. Nor are Michael Parenti or John Bellamy Foster or Ed Herman, or even Adam Phillips, say. The rise of TED level pop thought is the new cyber public — the electronic public. That relative morons like Ferguson or Dawkins are now elevated to the status of pop icon is hardly surprising. Back in 2001 The Nation ran an edition devoted to public intellectuals and mentioned Daniel Bell, Nathan Glazer, Michael Walzer, Christopher Lasch, Herb Gans, Paul Starr, Robert Jay Lifton and Christopher Hitchens. Again, horrifying. The reality is that the public as an idea is utterly colonized by entertainment. Soon I expect George Clooney or Angelina Jolie will make the list. In 2002 the New York Times held a poll of sorts for leading public intellectuals and Henry Kissinger came in first. I would be willing to guess a list compiled in 1960 or 1950 would be far less dreadful. Perhaps still reactionary at the core, but less stultifyingly stupid. But I digress.

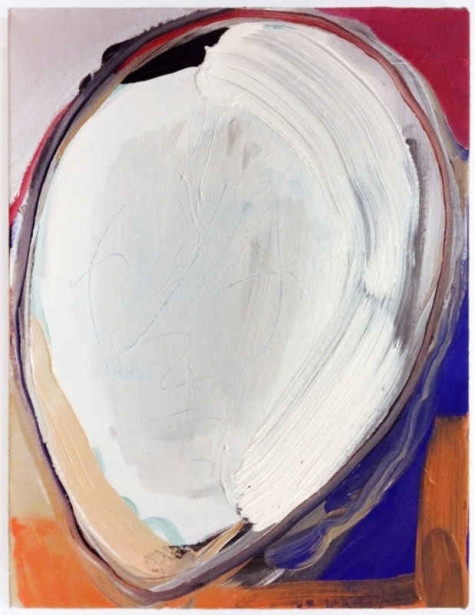

Heather Guertin

There is something in seeing how artwork, circa 2016, relates to questions of this nebulous public, but also to pleasure and morality. It is a huge discussion, but I wanted to at least touch on a few more ideas. Back in 2004, Sven Lutticken wrote…

“Where does this leave the notion of the public sphere as constituted – above all – by the

mass media? Every medium is based on selection, and in the case of mass media there

are immense interests at stake in this selection process. It can well be argued that the

mass media’s most important function is to hide and erase; to keep things from being said,

written, or shown; to prevent or pervert the formation of historical consciousness and thus

of a public, collective memory of a non-trivial nature.”

Of course, as Lutticken makes clear, bourgeois society always contained and controlled the public sphere. It was always exclusionary. In the 1960s however, there was a counter public sphere, but that evaporated over time until it was finally utterly gone by the early 90s. As Lutticken observes, the nostalgia today, created by mass media, is unlikely to feature the likes of William Burroughs (or a dozen others who were hugely influential during the post WW2 era and on through Vietnam). That shadow public which included anti war activists and artists such as Robert Bly and Allen Ginsburg gradually became diluted by those very artists collaboration with corporate mass culture. Burroughs became a commodity and the rise of corporate owned rock and roll figures (Patti Smith or whoever) came to stand in as a sort of ersatz avant garde. Behind this looms the actual public sphere, as it were, which is advanced Capitalism. By which I mean that the logic of capital leads inexorably toward Hiroshima, Falujah, My Lai and El Mozote. And everyone is implicated in this carnage to varying degrees. And this was really Adorno’s point about *right living*.

Richard Aldrich

Fabian Freyenhagen in an essay on Adorno, wrote….“…even if we do not participate actively and directly, to think that this would constitute right living would mistake a lucky and merely partial escape for more than it is. Even then, we would still be part of a guilt context, that is, we would still contribute to the continuity of a radically evil world.” The difficulty is that survival entails complicity. I have to pay rent or be put out on the street. In order to pay that rent I have to take a job and that job might well be part of a process manufacturing weapons or propaganda. Everyone has to eat, has to have shelter. So, one of the more profound realities of contemporary life in the West is that we cannot escape and our inability to do so engenders guilt and remorse. Our highly mediated sense of happiness always operates within a system of violence. And the cunning of the system is such that it promotes stigmatizing and shaming, behavior that we know, deep down (or should) is a form of projection. Even when we don’t, we do.

The snitch culture is not an accident. The society of domination has become increasingly adroit in its stealth granting of permission to project. Stealth dog whistle racism in presidential candidates is only a crass externalization of private feelings of resentment and belief in entitlement (for white people anyway). And such entitlement is only the compensatory mental formation born of guilt and rage. Happiness is so abstract a notion today that it is all but meaningless. The marketing of happiness usually takes the form of consumption of some sort. Leisure time, that which almost nobody has, is still an ideological bedrock belief. The privatizing of emotions runs alongside this. Self regulation. Still, artistic creation is never simple or one dimensional. Not even kitsch. It contains its opposite even if only in a latent form. And it is never as simple as a Barzun would have it. For the religious itself was always both more and less. We increasingly mirror our own artifice in how we express even basic ideas.

Aparicio Arthola

The snitch culture is an auto-critique of ourselves, operating unconsciously. It is also, of course, encouraged and coerced even by the authority structure. Agreement is reflexive and felt as if it is only a mouse click. Feelings are only clicks. Ephemeral and yet counted. Our emotional landscape now duplicates the contours of financialized society. People increasingly react to the learned cues taught by mass culture. And yet, there is a simultaneous recognition of a missing public space. Not only a material commons, but an intellectual space. Because again, even the indoctrinated know deep down that an educational system bankrolled by Bill Gates or George Soros is not really educating them or their children. That is the festering open mental and emotional wound that must be banished from our thoughts. But banishment is not as easy as one imagines. The banished return. And that ominous metaphor of return crops up even in kitsch TV shows. Something familiar is coming home to get us. And it disrupts our dreams and fantasies.

In Poe’s Masque of the Red Death, Prince Prospero decides to ignore the plague ravaging the countryside. He invites all the aristocracy to come to his castle where he throws a huge extravagant party. He welds the huge iron doors shut. Nobody can leave, nobody can enter. Eventually, after many months, the Prince decides on a masquerade ball. There are seven chambers each decorated in specific colors and styles. As Poe writes…“To and fro in the seven chambers there stalked, in fact, a multitude of dreams.”

At midnight a stranger, an intruder, in costume and mask, appears.

“It was in the blue room where stood the prince, with a group of pale courtiers by his side. At first, as he spoke, there was a slight rushing movement of this group in the direction of the intruder, who at the moment was also near at hand, and now, with deliberate and stately step, made closer approach to the speaker. But from a certain nameless awe with which the mad assumptions of the mummer had inspired the whole party, there were found none who put forth hand to seize him; so that, unimpeded, he passed within a yard of the prince’s person; and, while the vast assembly, as if with one impulse, shrank from the centres of the rooms to the walls, he made his way uninterruptedly, but with the same solemn and measured step which had distinguished him from the first, through the blue chamber to the purple –through the purple to the green –through the green to the orange –through this again to the white –and even thence to the violet, ere a decided movement had been made to arrest him. It was then, however, that the Prince Prospero, maddening with rage and the shame of his own momentary cowardice, rushed hurriedly through the six chambers, while none followed him on account of a deadly terror that had seized upon all. He bore aloft a drawn dagger, and had approached, in rapid impetuosity, to within three or four feet of the retreating figure, when the latter, having attained the extremity of the velvet apartment, turned suddenly and confronted his pursuer. There was a sharp cry –and the dagger dropped gleaming upon the sable carpet, upon which, instantly afterwards, fell prostrate in death the Prince Prospero. Then, summoning the wild courage of despair, a throng of the revellers at once threw themselves into the black apartment, and, seizing the mummer, whose tall figure stood erect and motionless within the shadow of the ebony clock, gasped in unutterable horror at finding the grave-cerements and corpse-like mask which they handled with so violent a rudeness, untenanted by any tangible form.

And now was acknowledged the presence of the Red Death. He had come like a thief in the night. And one by one dropped the revellers in the blood-bedewed halls of their revel, and died each in the despairing posture of his fall. And the life of the ebony clock went out with that of the last of the gay. And the flames of the tripods expired. And Darkness and Decay and the Red Death held illimitable dominion over all.”

Speak Your Mind