Heinrich Riebesehl, photography.

“I saw an angel in the marble and carved until I set him free.”

Michelangelo

“Nature produces similarities; one need only think of mimicry. The highest capacity for producing similarities, however, is man’s. His gift for seeing similarity is nothing but a rudiment of the once powerful compulsion to become similar and to behave mimetically. There is perhaps not a single one of his higher functions in which his mimetic faculty does not play a decisive role.”

Walter Benjamin (On The Mimetic Faculty)

The relationship of art and ideology is very complex. At the most rudimentary level the idea of agit-prop theatre, for example, is nothing except ideology. That is its intention. Does that mean it is less important because of that? Well, define importance. Is anything in art important? I happen to think so, yes. And yes, I think that agit-prop can be a great service, and useful, and in its way important. But I don’t consider it art. Art must touch on something, as Adorno said, *non-identical*. There are artworks that are ideological, obviously, and its possible to think that all art is ideological to some degree. But if you do that then everything becomes ideological. But art that is revelatory is that which subsumes ideological meaning in its form.

Photography is highly elusive if we break down individual photographs. But why, for example, are abstract photographs so problematic? I think for the same reason that abstract films are problematic. The camera in both cases is this mediating factor. But more on that below. First, I want to look at a few things in relation to art criticism. Boris Groys writes, from his book The Total Art of Stalinism….

“The art of socialist realism has already bridged the gap be tween elitism and kitsch by making visual kitsch the vehicle of elitist ideas, a combination that many in the West even today regard as the ideal union of “seriousness” and “accessibility.” Western postmodernism was a reaction to the defeat of modernism, which could not overcome commercial, entertaining kitsch, but after World War II was, on the contrary, increasingly integrated into the single stream of commercial art controlled by the demands of the market. It was this circumstance that prompted many artists to undertake a skeptical revaluation of values and renounce the modernists’ totalitarian claims that they represented a chosen elite and new priest hood. These pretensions have now been succeeded by others, as individual creation is repudiated in favor of quotation and ironical play with the extant forms of commercial culture. This shift, however, is intended merely to preserve the purity of the artistic ideal. Purity was previously attained through the search for new individual and “incomprehensible” forms. Today, however, since that quest has been appropriated and is encouraged by the market, the artist turns in the name of purity and independence to the trivial, regarding this reorientation as a new form of resistance to the will to power he perceives in others but not in himself.”

Dashiell Manley

The first problem here is the idea that modernists claimed something totalitarian. Which modernists might that be? I mean that is just far too general a comment to even have meaning. And who among the modernists claimed the status of high priest? This sort of petulant rhetoric cloaks a subtle hostility toward culture, usually. And who, which artist, has turned ‘in the name of purity’ toward the trivial? And who was supposed to have ‘previously demanded purity’. Secondly, that paragraph raises questions having to do with popularity, with the idea of popularity. For popularity is linked to capitalism. Popular means economically successful. Well, in part, for there is certainly work that is economically profitable which one would be hard pressed to describe as popular. Much work is canonized that very few people care about or even know about. In a non Capitalist society popularity becomes something else, but I doubt seriously “accessiblity” has ever or will ever be a virtue. So, no, there is no union of serious and accessible. Who asked for that anyway?

Groys book is a history of Soviet art with a focus on the Stalin years. What interests me here, though, is the blurring or confusion over social organization and cultural production. And then how ideas of popularity creep into such topics, and more, how all of this is permeated with the Western notion of progress (or say, Enlightenment values). Art may indeed, as Malevich and others believed in the 1920s, be an unconscious production, but that hardly frees it from history or society. The sort of kookie Khlebnikov notions on language and grammar for example are the far end of a desire for control, really. A universalizing and essentializing tendency and project.

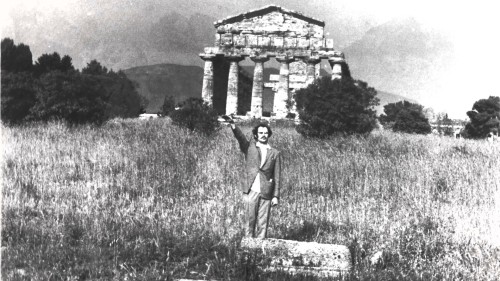

Miquel Barcelo

“The novelty of the contribution made by avant-gardists such as Malevich and Khlebnikov, however, is not apparent from such parallels. Central here is the radical notion that the subconscious dominates human consciousness and can be logically and technically manipulated to construct a new world and a new individual. It is on this point that the early avant- garde of Malevich and Khlebnikov was radicalized by their followers, who considered that suprematism and transrational poetry were too contemplative, since, although they contemplated the inner “subconscious” construction of the world rather than its external image, they did not break completely with the cognitive functions of art.”

Boris Groys

Groys goes on to argue that … “Avant-garde artists, on the other hand, to whom the external world has become a black chaos, must create an entirely new world, so that their artistic projects are necessarily total and boundless. To realize this project, therefore, artists must have absolute power over the world—above all total political power that will allow them to enlist all humanity or at least the population of a single country in this task. To avant-gardists, reality itself is material for artistic construction, and they therefore naturally de mand the same absolute right to dispose of this real material as in the use of materials to realize their artistic intent in a painting, sculpture, or poem. Since the world itself is regarded as material, the demand underlying the modern conception of art for power over the materials implicitly contains the demand for power over the world.”

Well, ok, there is really a lot wrong with this paragraph. Now in the context of post Revolutionary Russia, against the backdrop of societal trauma and destruction and regeneration, there were certainly trends that looked to the creation of a new world. A world built around socialist ideals. That many artists saw this in the terms Groys enunciates is also no doubt true. But it is just as true that many didn’t. For there are always ideological imprints, and beliefs at work in art making. But this is true of almost any historical period. Even those painters, commissioned by the Church, say in Florence or Rome, or in Spain — they may have still seen the world in very religious terms, but their work contained much that was outside the tenants of Church doctrine. I don’t want to dwell too long on Soviet art here, but it is worth noting (as Groys does) the multi faceted approach of the constructivists of the 20s; Tatlin and Rodchenko and others, and that all of this must be seen, too, in the extreme transformative period in which all this took place. The issue though is that when artists look to implement theoretical beliefs (and this true of even, say, programe composition such as Berlioz and Vivaldi) into their work the result is often to narrow the meaning of that work. As a sort of side bar observation on this the programe compositions of many film composers, whose work was mediated by the demands of scoring for film, were very much more successful, i.e. Shostakovic and Prokofiev. And there is a truth in this observation that I will return to below. The point, though, is that ideology fails artistically, when imposed from above. It is always there, organically, anyway, for all artists, all of us period, are ideological beings. The artist then must be aware, and even self analyze to some degree, without creating according to ideological formula. Art can and often does contribute to social transformation, but never directly. Just as music often conjures, say, the vast prairies or tundra, or whatever, without directly imitating the sounds of winds from the north or cicadas.

Mark Ruwedel, photography.

Groys sees Stalin era ‘socialist realism’ as a kind of logical culmination of the Russian/Soviet avant garde of the early 20s. He also writes…“Stalinist culture both radicalizes and formally overcomes the avant-garde; it is, so to speak, a laying bare of the avant-garde device and not merely a negation of it.” Well, actually no. In fact I’d probably argue both of these points although certainly the first outpouring of creative energy in the U.S.S.R. was extraordinary. It did not lead by its own logic to socialist realism. But the argument makes sense if you accept the idea that early Soviet avant garde thinking was purely totalizing and Utopian. Some was, but not nearly all. And Groys, to be clear, acknowledges this (sort of). The Contructivists had as an overriding principle the desire to remove artificial separation of art and life. And this was Utopian, but problematic. For it is envisioning a too limited notion of what artistic creation entails . That said, there is no denying the immense artistic developments of those early Soviet artists. The social transformations were being played out in the cultural sphere and probably even exceeded them in some respects. The point here though is not to argue socialist realism or even Soviet Utopian thought. There is also the fact that the revolutionary vision of the early Soviet artists was so ambitious that it did (per Groys and also, I think Paperny, the *other* notable critic of Soviet era art and architecture) in effect subsume modernism as it was seen by the West. Groys argues this resulted in a kind of pre-post modernism in the sense that it was citational, subverting of traditional hierarchies, fragmented and contingent. Perhaps. But it was certainly a very different kind of post modern. And since *post modernism*, like *modernism* are not things that fall from the sky, the premise of this line of thought is fraught with contradiction. Also, Socialist Realism resembles nothing so much as Norman Rockwell by way of Grant Wood and Thomas Hart Benton (and the entire Ashcan school, in fact). The idea of style was in a sense depersonalized, with the unfortunate affect of turning realism into illustration. Not surprisingly the best work of the Stalin years was in poster art and graphics.

Alexander Deineka, 1928.

There is an intriguing sub plot here that Groys introduces; that modernism itself might be seen as an expression of the bourgeoisie in crisis. And that crisis was not at all the crisis of the early Soviets (if it can even be said that they had any crisis in the early 20s). My problem with such ideas, and Groys is not alone in this, is art is being conflated a bit with social movements. Art does reflect such transformations (or lack thereof) and in rare instances may even foment them but this isn’t a relation of the identical– art is not a single thing, not a single idea or single response. Culture reflects certain aspects of society but it also exists at times in a very heterogeneous realm. The manner of reflecting society is multi tiered and complex. It is also worth noting the radical journals and pro socialist art of the West from the 1930s — The ‘John Reed Club’, and the ‘Artists Union’, and American social realists associated with this; Ben Shahn, Stuart Davis, Louis Lowozick, et al. It is exactly the question, though, as to what was the more radical culturally…the work of Shahn and William Gropper and Davis, or the work of Surrealists, the Abstract Expressionists a decade or so later, but lets say the early precursors of that, and of Dada. It’s not a fair or valid question, I realize, but its not without value as a thought experiment. For when I say the work of Soviet socialist realism became at best a form of illustration, it is important to ask why or if that is a bad thing. And my answer is, well, do we call Rembrandt an illustrator? Or Michaelangelo or Durer or Goya? And Goya as a case in point is very revealing of this issue. The Caprichos *are* in a sense illustration. And they both criticize a harsh reality, and social injustice, but they also by virtue of the mimetic quality, the technique and vision of Goya himself, become always something more, something closer to metaphysics. And somehow the Caprichos never reproduce very well. There is something ineffable about seeing them in person, together as a collection, that creates something deeply haunting. The ‘Black Paintings’, those last personal canvases that Goya made are something like the cave drawings that exist in remote chambers far from the view of the group. They are inexplicable in many ways, and certainly not realistic in any traditional sense, but they are also like some private inscription on the metaphoric wall of Goya’s brain. They are also mysterious. Goya never thought of who, besides himself, might see them. It is that final quality of disinterest in the viewer that gives them additional weight.

In any case, there is a rather large difference between Shahn and Goya for example. The Constructivists were visionary regardless of what ideological or theoretical explanation they attached to their work. Tatlin and Rodchenko (later arrested for his pine tree photographs, which were accused of plagerizing a decadent West). The Mexican muralists come closest to a genuine union of polemic and metaphysics. And it is worth noting that Mexican (and Latin American) modernist architects emerged after WW2 as among the most radical and significant in the world.

There were, it should also be noted, some socialist realist painters, Alexander Deineka particularly, who avoided the kistch sentimentality of Roses for Stalin. Deineka seemed to straddle the graphic design world and that of draughtsman trained realist.

And this, sort of anyway, segues back to questions of how and why humans create things. So I will digress a moment or two…

Clifford Ross, photography.

The artist is not providing information about reality. Not describing reality. This is just not what art does. Art is neither moral instruction or political advice. Now, whenever such topics arise it is useful to reflect on the fact that all societies have produced artworks of some kind. Humans create. And so the question becomes why and for that reason this seems to always happen. The earliest evidence of human creativity is in stoneage Africa. This is probably roughly twenty thousand years before the Paleolithic *revolution* of 45 thousand years ago. And the idea that this revolution signaled a sudden and radical transformation of human consciousness is now being widely challenged. The problem is that the materials in south and central Africa were mostly perishable and hence its impossible to know exactly what was being done at this distant time and just how sophisticated it might have been. But there are a handful of stone carvings and some bead work, and the implication of tattooing of some sort.

Gillian Morriss Kay writing on early prehistoric art…..“The cognitive activity underlying pattern-making is complex, involving planning and intention, but the original idea of pattern may be a function of the brain: nested curves and zig-zag patterns are characteristic of entopic phenomena (Clottes & Lewis-Williams, 1998), i.e. images seen in altered states of consciousness such as that preceding a migraine, in a schizophrenic hallucination or induced by temporal lobe epilepsy or certain drugs (as utilized in the psychedelic art of the 1960s and 1970s). Although the examples of early patterns mentioned above have been taken to imply symbolling activity, this is not necessarily the case. Seeing an entopic image ‘projected’ onto a surface can lead to a desire to draw it, simply to make sense of seeing this unbidden pattern…” This patterning is seen as far back as 60 thousand years ago in parts of Africa. The suggestion is though, that something happened, somewhere along this long timeline that allowed early humans to hold an image in the mind’s eye. The first drawing on flat surfaces (stone) occur roughly 40 thousand years ago. Many more have been found dating to 15 to 25 thousand years ago. Many in Africa, and a great many more in European caves. Now there is work that has been argued to have Shamanistic meaning (a man with the head of a bison, etc) but in a way I find this to be a moot point for such work is probably many things at once. And as Leroi-Gourhan has argued, those early cave paintings in (mostly) France must have also represented something of an alphabet, or pre-alphabet and one linked to developments of language and speech. For to call it Shamanistic is a modern conceit. What does that mean to someone living in those caves forty thousand years ago?

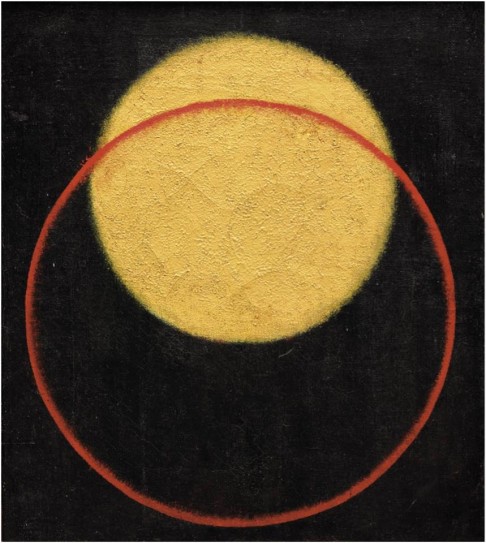

Park Se Bo

“Painting with a conscious aim to portray symbolic content for communication with the viewer is inherent in the work of mature artists, in which category I include the artists of Lascaux and Chauvet (although Chauvet also contains many engravings and finger-drawings of lesser artistic skill, see Clottes, 2008). Rothko and his fellow artist Adolf Gottlieb, replying to a New York Times critic’s comments on a 1942 exhibition of their work, wrote that art is ‘the significant rendition of a symbol’; in their manifesto of aesthetic beliefs, they asserted that the point of a painting did not lie in an ‘explanation’ but in the interaction with the viewer, who must be persuaded by the paintings to see the world ‘the artist’s way’, not his own way (Baal-Teshuva, 2003).”

Gillian Moriss Kay

And this gets closer to the way art needs to be talked about. For the viewer is not separated from the artwork. Nor from the artist, finally. All art requires a social context and a social context implies an historical context. Those early African people who migrated north to Europe were already creating what can be called *art*, so humans were neurologically ready as early as 60 thousand years ago to produce artworks. The explosion (sic) in Paleolithic Europe was the product of geography and materials and probably weather to some degree. But this idea of presentation is crucial to how art should be discussed. The audience and viewer are part of this project notwithstanding work created in remote channels of caves where clearly almost nobody would able to see it.

Adolph Gottlieb

“Great apes are acutely sensitive to the direction of others’ gaze. Determining the precise direction of another’s attention is an important ability because it can provide salient information about the location of objects such as food and predators. In social settings, a great deal of information is communicated by means of following other individuals’ gaze to specific individuals or to call attention to specific events.”

Chet C. Sherwood et.al.

Benjamin believed that ancient man had a more highly developed sense of the mimetic, by which he meant a larger set of correspondences and relationships tied to mimesis and a more intense focus on this practice. One sees the residue of these ancient connections and analogies in children. But he saw the erosion of mimesis, as he understood it in early man, being tied to language and the conceptual; where representations or non-sensuous similarities have replaced the primordial faculty of the mimetic. But there are problems with this idea because early man also was following an impulse toward creating an alphabet, and linking speech to these new signs and symbols. Benjamin was aware of this, and saw in language a kind of evolution of mimesis, a migration of early occult practices into conceptual formulae– and to the degree that magic and the occult had completely disappeared. The liquidation of magic as he put it. And this was, for him, where dis-enchantment resided. Michael Taussig writes…

“For centuries, the severity with which the rulers prevented their own followers and the subjugated masses from reverting to mimetic modes of existence, starting with the religious prohibition on images, going on to the social banishment of actors and gypsies, and leading finally to the kind of teaching which does not allow children to behave as children, has been the condition of civilization.”

Michael Grieve, photography.

This is what Adorno and Horkheimer saw as the prohibition, or more, the control of mimesis. The limiting of it. The technological reproduction (copying) of images has created a kind of new magical relationship between perception and object. The reliance today on screen image, and its nearly infinite circulation has been ideologically mediated. Taussig is very good on how colonial appropriation plays a part in this and its certainly true that the Western advanced (sic) world works off a model of appropriation that sees it as a kind of given. Common sense today means an acceptance of mass appropriation. But it probably even goes beyond that.

The administration of children has been acute, of course. Play is increasingly regulated now. And from an early age, which means those mimetic dreams of childhood become performative mandates. Now, the relationship of the collective, of society as a whole to the cultural products it creates, or manufactures (depending on your ideological point of view) has changed substantially over the last forty years.

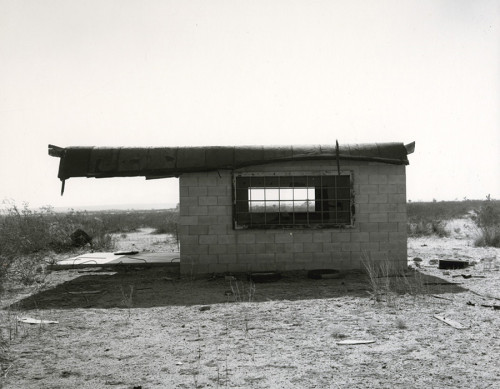

Hermit Castle (David Scott, builder, 1955). Scotland.

“There is only one language which is not mythical, it is the language of man as a producer: wherever man speaks in order to transform reality and no longer to preserve it as an image — — myth is impossible.”

Roland Barthes

Tarfuri saw the effects of capitalism on architecture, and on social structures generally. Brian Oliver is his excellent book on Benjamin and architecture, devotes a good amount of time to Tarfuri. And it is useful in light of Groys book to examine Tarfuri’s analysis of Capital and space. Tarfuri said that architectural and urban theorists (of the 1920’s) ended doing little more than creating a “plan for Capital”. But that is also teetered between Utopia and realism. And this tension was exemplified by the various housing projects of Europe in the 20s. The limits of Utopianism were revealed by market constraints (a rise in the cost of raw materials, etc). Benjamin though, was fascinated of course with the arcades of Paris, as residue of utopian dreams inscribed in ruins. And today’s *ruin porn* speaks to this dream as well. The viewer is pulled toward these failed sites as they are toward dreams, to a sense of what something missed. And what is missed (well, one of the things that is missed) is that sense of unregulated dreaming. For the ruin speaks to something not just failed, but impossible. And it transforms itself into mythology. The danger, as Benjamin noted, was in a desire to retrieve the Utopian dream. The flip side of that is an insistence on a belief in technological progressivism. This was partly the tension in Soviet art, too.

David Noonan

“Benjamin’s utopianism is thus concerned with ‘archeaologies’ of rather than blueprints for the construction of the future. In analogy with Benjamin’s attempts to unlock the personal sense of the present state through recollecting his childhood experience, politically progressive utopianism can never be finished with working through the past.”

Brian Oliver

Benjamin was seeking the conditions and origin of modern urban life. What he called a genealogy of urbanization. In essence the search was born of an ambivalence about modernist dwelling, the shift from the Victorian era bourgeois home with its Oedipal strife and sense of suffocating refuge from the Industrial trauma of new city congestion to the machine homes, the enactment of Utopian social engineering and decorative austerity. How as it that humans evolved from caves to Gothic cathedrals to Le Corbusier? How does the rationalization and instrumentalized control of mimetic practice play into this? Adorno and other saw the role of art as crucial to answering some of this. Benjamin did, too, but perhaps from a more dispassionate distance. Or fatalistic? On the northern coast of Scotland there is a small mostly forgotten sand/cement dwelling, very small really, designed and built by architect David Scott in the mid 1950s. He built it but then left. It once had stained glass windows, but now mostly resembles an abandoned WW2 bunker of some sort. It is ur-Brutalism. But it is also deeply Utopian in the sense that it knows itself as failure, and as such is oddly moving a home for nobody. If Wittgenstein’s house was fit only for Gods, this is a home fit only Paleolithic cults. Still, it is oddly compelling and very childlike. People will, today, imagine it a Hobbit house. And it is at the least a structure out of Grimms. Such small eccentric personal creations harken back to something we sense from childhood, building forts or secret hiding places to escape parents and authority.

Danila Tkachenko, photography.

The Utopian gave way to Capital. Mass housing defaulted to cost effective neo-factory or prison templates. And this was the trajectory of 20th century building. Architecture receded to giant prestige projects, to concert halls and mega malls, or elite small boutique edifices that showcased one or another starchitect. This mirrored the market forces shaping fine arts in the final third of the century,too, and certainly onward to the contemporary reality. Artists, removed from mimetic connections and associations, resort to conceptual ideas about mimesis without actually expressing the enchantment. Of course some do, but even the best artists today, in painting or installation are commenting on that gulf, and perhaps that is all that is possible. And it is an intriguing discussion to look at abstract painting, say, and try to articulate why one artist feels different, more convincing and accomplished, than another. And there IS most certainly a difference. I wrote before about the Korean abstract art from the second half of the 20th century (Dansaekhwa) and how almost unarguably effective it is. Chung San Wha, Park Se-Bo, Chung Chang-Sup,Lee Ufan and my favorite perhaps, Yun Hyong-Keun; and then compare to the most pedestrian of what has come to be called Zombie abstraction. And yet, to articulate these differences is difficult because it is in exactly those qualities that defy description, defy language, that the differences occur. And difference itself is a definition of mimesis. Difference and similarity. Louis Biggs called Chung’s work analogies and not images. Some of this is just the sensitivity to materials, the quality of care expressed in the visible time taken. And that is maybe the thing most different from a Rothko or Kline; the Korean artists are slowing down the process. Down to a standstill finally.

Vladimir Tatlin (1914).

The broken promise of art (culture) that Adorno alludes to is part of the definition of how modernism died (sic). In a sense this is an echo of Groys argument, and certainly the mass culture of the west has come to disenchant and neutralize radical expression. But this entire discussion returns to the strangely western notion of realism. Terry Eagleton wrote a great (and well known) review of Eric Auerbach’s Mimesis. This was in 2003. Which was fifty years after the book first came out. Anyone in English lit classes has read at least part of Auerbach’s book.

“The human subject becomes the blindspot at the centre of the picture, the absent cause of the world’s coming to presence. For the Modernists, this is a problem which is resolvable only by irony – by representing and pointing to the limits of your representation in the same gesture.”

Terry Eagleton

Willem De Kooning

“Modernist and avant-garde Marxist artists of the early 20th century, the whole point was to overthrow existing representations, complicit as they were with the dominant political power. Indeed, they wanted to overthrow the act of representation itself, partly because it was not clear how you could ‘represent’ a reality which was changing and contradictory without striking it dead in the process. How do you take a snapshot of a contradiction?”

Alexander Rodchenko, 1918.

This is where notions (like some of the Constructivists) of merging life and art starts to become problematic. Brecht said what is realistic changes. Strictly speaking realism is regressive. It is ideologically complicit with the status quo. Even if the writer, say, is writing about radical revolutionary subject matter, the world he or she is creating, if realistic, is one that the reader tacitly accepts as consistent with daily life. Now Benjamin saw a continuity running from Homer through the Third Reich, where Auerbach sort of only implies it (and Lukacs rejects it), but nonetheless privileges realism as a representation of the daily life of the people. For Auerbach is, paradoxically perhaps, a populist. He is disdainful of this bourgeoisie in crisis. The chapter that compares and contrasts Homer and the Old Testament is probably the most famous. And justifiably so. I have never been sure if Auerbach was quite fully aware of the implications of what he wrote of the Old Testament. I’m not sure Eagleton is, either. For in Homer the world is described with the intention of accuracy. In the Old Testament, there is no intention to describe details. What matters is the appearance of religious activity, of God. Voices appear out of the dark, and vast deserts are crossed in a single sentence. And this is allegory, or the basis for it. Auerbach was influenced by both Christianity, and the Enlightenment. For him the business of progress mattered a great deal. His harshest criticism is for work that forgets the common man. One is never quite convinced that he really believes this, but it suits his project so he persists. But in the end realism is an idea that survives almost because of its vagueness. It is interesting here, looking at painting (or sculpture) to see that Viktor Shklovsky, writing on Tatlin in 1921, said the most important quality of an artwork (a construction) was its faktura, its surface quality, texture and that which convinces the viewer of its having been made (created). This is oddly not so very far from abstract artists in the mid century West. Franz Kline was really painting, in part, about his own brush strokes. But in so doing was creating work about a good deal more. Osip Brik, the art critic, wrote in 1918 that the artist was now more engineer and technician, ‘constructor’. Art was being framed more as a very particular kind of work. All of this may not really be important per se, but it does lend some credence to Gorys idea of a sort of premature post modernism appearing in the U.S.S.R. as the early explosions and rapid development of art and culture were being coerced, in a sense, into socialist realism.

That said, the point here is that it is not difficult to argue that De Kooning is more realistic than Gainsborough. And yet why would many people, if not most people, laugh at this idea?

Alexander Rodchenko, photography. 1933.

When Rodchenko asked ‘Why depict life, if one can influence reality and make it embodiment of your ideals and aspirations?’ he was being polemical at a time when Utopian thought had a firm material and societal basis. Notwithstanding however, there remains something in such sentiment or purpose that is losing sight of that inherent ambivalence of all mimetic activity. For is the goal of any art, at any time, been to influence reality rather than represent it? And if it’s not representation, then it’s pointless to discuss it as art. Culture then disappears and life becomes a great Dionysian orgy of endless creativity. Which sounds terrific, but lurking at the edges of this idealism are questions of that original ceremonial or ritual correspondence that Benjamin suggested. The Utopian is problematic exactly because it is reductive. And this is where I think Adorno is so key. For Adorno believed that art, and not just modernism, was always inscribing an historical suffering. And if one believes suffering can be eliminated, then I think that is probably delusional. It can be reduced. I am with Freud on that. We can alleviate the pain, but we cannot eliminate it. Reality is not a *thing*. And this is perhaps the final verdict on such ideological arguments. I mean go ahead and define *reality*. Even just explain it. Is Kafka a realist? Is Beckett? Is Melville? Is Conrad or Nathanial West? One cannot define it, and arts role, or among its chief roles, is to point toward where and how it might be.

Hannah Starkey, photography.

Photography, to return to my comment at the top, uses the technical apparatus — the camera. The camera makes everything realistic to some degree. The camera is recording light and light off surfaces. That is all. And yet that is very much different than even what Hyper-realist painters are doing. For the hyper realist, or super-realist are still not really trying to duplicate reality but rather improving upon it. A thirty foot close up painting of a doughnut is a doughnut as only a microscope can observe it. And this is something even Auerbach touches on. The horizon, the gaze toward the horizon. Howard Hawks in that sense is the Homer of film directing. Camera always at eye level. And then Ozu, whose camera was always very low as he sat on his tatami mat, would be the Canaletto or something. A favorite novel of mine and one I regard as among the best of the past thirty years is How Late it Was, How Late, by James Kelman. And in that novel the narrator has gone blind from drink. A petty criminal Glaswegian drunk whose stream of consciousness is as magnificent as anything in Rabelais or Chaucer. I bring it up because it is also the least optical of novels and one in which, were it filmed accurately, would necessitate a black bag over the camera lens. The camera is tied to verisimilitude . And it cannot be escaped.

From the Kelman…“Dear o dear he was stranded he was just bloody stranded. Bastards. Fucking bastards. Fucking joke. Fucking bastards. Sodjer fucking bastards. Sammy knew the fucking score. He knew the fucking score. He gulped; his mouth was dry, he coughed; catarrh; he bent his head and let it spill out his mouth to the pavement. He was still leaning against the window, now he pushed himself away. A groaning sound from the glass. He stepped sideways. He needed a fucking smoke, he needed a seat, a rest. This was crazy man it was fucking diabolical…”

Francisco Goya ( Tio Paquete )

There is no way to emphasize just how good that paragraph is, how outstanding the technical skill of Kelman. For that voice, that particular rhythm establishes character. There is something horrible and funny both in that voice, and something almost tragic as the book moves on. But that is is not a visual scene. It is realistic in the sense it captures how peopl talk. But is it realistic? The images are verbal, demotic, and the quality of sensuality is that of urban cold, sharp, unfriendly. It is a heightened reality. It is also a kind of realism that Lukacs would likely reject. And it begs the retirement of the term *realism*.

The camera is technical, and it mediates, as it also introduces a quality of chance into the photograph. But the West has come to link optical recording (photographic images) with evidence to some degree, with reliability. Some of this is political — the state wants the public to fear surveillance and believe in its reliability. But another aspect is that people in the West today worship technology period. It is equated with science. And with the figure of the technician. The director, the manager, the consultant. The repairman. Whatever it is, the machine is now a kind of gestalt jury on our consciousness. Now, Adorno’s primary complaint against realism was what he called “reconciliation under duress”. He saw realism as a false reconciliation that ignored the actual antagonisms and breaks between subject and object, and that Lukacs was deluded in seeing the reconciliation as affirmative. The belief in the realistic being realistic is one that ignores the human psyche and treats the individual as undamaged. Adorno saw social oppositions as sedimented in the modernist artwork. The key, and this is true for Benjamin, too, was that contemporary society was too complex and contradictory to allow for resolution in representation. No systematic theory or philosophy can express this, and no global theory — that, in fact, might be possible as social movement. For social movements are concrete but not total. The disenchantment of the world has already taken place. And Auerbach helped trace that disenchantment. The writing of Kafka follows that of the Old Testament, revelatory and allegorical. Realism followed upon Homer (and perhaps by way of the Third Reich but certainly, partly, ends up in Madison Avenue marketing firms). It is not an accident that marketing and propaganda employ conventional notions of realism. Lukacs critique is Utopian — is the promise of liberation. Adorno sees liberation, or the potential for it, dialectically. In other words the contemporary world is irreducible. And any reconciliation is a lie.

Anselm Kiefer, photography (Heroic Symbols).

So, the idea of evaluating artworks must include some examination of how and why all humans created things. All cultures create things that might be called art. At one end is decoration, but often, as in Islam, of a transcendent quality. At the other end is Bach and Durer and Goya and Melville. Without allegory in representation there is going to be some degree of historical loss. And for Adorno that was unacceptable. Steven Connor’s reading of Beckett comes to mind; “But it’s possible to see Beckett moving in another direction, too, towards an ever more intense awareness of the predicament of immanence.”

As Peter Uwe Hohendahl puts it, regarding Adorno …“…he opposes a form of aesthetic criticism that begins its work with an uncritical acceptance of the outside world, and uses this world for as the norm for the evaluation of the artwork.”

Speak Your Mind