Cildo Meireles

“{Imperialism}is an act of geographical violence through which virtually every space in the world is explored, charted, and finally brought under control.”

Edward Said

“The nineteenth century was the age of scientific exploration—-

Darwin in the Beagle, Livingstone in Africa, Powell in the Rockies, and

so on—but the sources of support for these efforts tended to be institutions

with very practical interest in the regions being studied. Paralleling all of

this was the great surge of missionary activity that supported some

exploration (including Livingstone’s) but most crucially led to the

gathering of important, detailed, information about ethnography,

languages, and geography by hundreds of dedicated missionaries throughout

the non-European world. Also of great importance were the detailed

reports that colonial administrators everywhere were required to submit,

reports providing information about native legal systems, land tenure

rules, production, and much more.”

J. M. Blaut

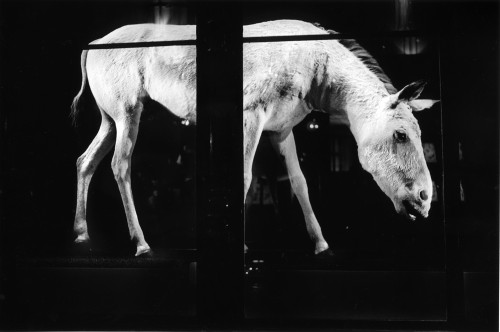

“If there is feeling in Bacon, it is not a taste for horror, it is pity, an intense pity: pity for the flesh, including the flesh of dead animals…”

Gilles Deleuze

“Fell long before; nor aught avail’d him now

To have built in Heav’n high Towrs; nor did he scape

By all his Engins, but was headlong sent

With his industrious crew to build in hell.”

John Milton, Paradise Lost

Jane Jacobs observed that the colonizer created (what she called) ‘imaginative geographies of desire’, which ‘hardened into material spatialities’. The obvious expression of this, per Jacobs, were maps and naming. The various prejudices and biases of Western cartography are pretty well documented, but this idea of mental mapping is less discussed. Now, the cartographers were entwined in a relationship with property and with law. Or rather, law is itself often shaped by perceptions of landscape and these imaginative geographies of desire. If not desire, then at least reactive hoarding, for I am not sure, entirely anyway, that the Colonizer ‘saw’ in ways that were precisely constructed through desire. But maybe what I mean is that the gaze of the plantation owner or colonial magistrate as he took in the panorama of the vast land over which his country’s military subjugated and subordinated the indigenous people, was looking less after what “he” wanted, and more about what he imagined was right, natural, and representative of God’s will (and the King or Queen’s). The British in India did not, after a while, desire that land, those subjects, and felt more aggrieved by the heat and dust, the differences in natural flora and fauna from their homeland, and this desire was more akin to a kind of resentment and aggression. A hatred.

Paloma Varga Weisz

Dan Glazebrook wrote about the current movement to reform English language education in the UK and commonwealth, by examining the legacy and history of Cecil Rhodes, after whom is named the Rhodes Scholarship.

“Cecil Rhodes was the archetypal British imperialist – a tyrannical stealer of land, ruthless exploiter of labour and rabid butcher of men, women and children. By the 1890s, he had conquered around one million square miles of territory (including modern day Malawi, Zimbabwe and Zambia) and laid waste to its inhabitants, using the newly invented Maxim gun to massacre all those who stood in his way and forcing many of the rest into the living graves that were his company’s diamond mines. As Prime Minister of Britain’s Cape Colony, his policies laid the basis for what became the apartheid system, as he forced Africans onto reserves, introduced segregation and forced labour, and systematically excluded Africans from voting, explaining to the Cape Assembly in 1887 that “the native is to be treated as a child and denied the franchise. We must adopt a system of despotism in our relations with the barbarians of South Africa.” What exactly this meant was spelt out in one of his more prosaic pronouncements: “one should kill as many niggers as possible”.

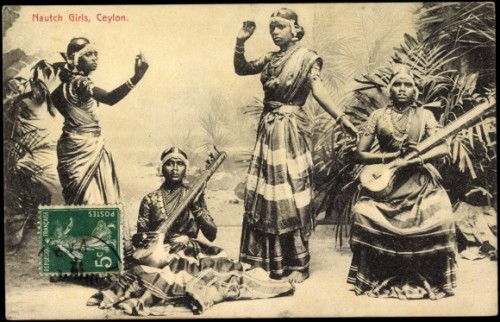

There has been a validating recently, though, of the symbols and style associated with fascism. One of the branches of that trend has been a sort of manufactured nostalgia for colonialism. Advertising has relied on colonial imagery for a long time now, and to a lesser degree Hollywood as well. Anytime one sees Victorian settings for narrative, even in brief commercials for example, it is almost always done with a kind of warmth and bathed in that amber light of the nostalgic. Even TV shows that ostensibly seem critical of the period have a way of cleansing the realities of colonial practices. One will often see poverty represented in Victorian settings, but one almost never sees the colonies themselves where white colonizers subjugated entire populations. The recent Indian Summers series from the BBC was sort of a mixed bag in that respect, but at least the sense of irrational British domination of even minor details of daily life was for once presented with some clarity.

Vincente Carducho (Stigmatization of St. Francis, early 17th century).

It is always interesting to read Medieval literature because it marks the real separation from us, and maybe that cut off point is 1492. Or thereabouts. The Medieval mind was not driven to posit a superior space that was Christian. The superiority was religious, but had not yet taken on these more modern ideas of progress and of what Blaut calls *inside and outside*, or the diffusionist theory of progress. A Eurocentric (largely) model of the globe. And of history. The early middle ages simply did not care about such models. The growth of exploration by sea, the discovery of the *new world*, raised questions for European religious thought. This really marked the change in spatial elitism. Or the birth of it, really. Someone had to explain what to do with those troublesome natives. And quickly to find a justification for enslaving them. The Spanish court saw only immense wealth in colonial subjugation, and while the Church was mostly in sync with the royal houses, culturally the ideas of inside and outside took longer to find formalized expression.

The hyper-colonial phase for Europe began around 1800. Maybe, a bit later, after the Napoleonic wars. And this hyper phase continued without interruption until the end of the 19th century, really. The classical colonial arc is maybe 1810 to 1880. What affects this had on European white thinking is not easy to tweeze apart from other factors, for it’s all a piece in the end. But what I have never fully understood in this evolution of societal expansion is the sadism and gratuitous cruelty of the colonizer, nor the need for such hysterical hierarchical anthropological explanations. The subjugated colonized, from Africa to South America to Asia were quickly catalogued and described as inferior, beastial, insensitive, and morally lax. All manner of pseudo scientific garbage was manufactured to justify the brutality of the European conquerors.

Simon Norfolk, photography. Afghanistan 2009.

However, I’d argue that the most significant period of time in European history, and one with the largest affect on the rest of the world, was the Thirty Years Wars that began in 1618 and lasted until 1648. For the Thirty Years Wars was the transformative period for Western consciousness and it marked the end to some earlier vision of life and the world far more closely related to ancient times. To pre-history. Life in Europe in the 1500s was profoundly different than life in the 1700s. In China, the Portuguese established an outpost and trade in the 1550s. The immanent fall of the Ming Dynasty at the same time — this was the 300 year rule of the Mandate of Heaven claimed by Zhu Yuanzhang in 1368, echoed throughout the world. The Ming had far greater impact overall than any European society, and its collapse, more or less at the same time that European colonizers were reaching Asia, was hugely significant. (as a side bar, the supposedly greatest earthquake in history occurred in Shaanxi in 1556, killing something like 30% of the population. And it is interesting that China suffered a disproportionate number of quakes in the 1600s. But there was also the Black Death, bubonic plague which occurred throughout Europe in the 1600s, also erupted in China, in particular in 1641. But the plague stretched across Persia and India, and the steppes of central Asia as well. Still, arguably the effects on China were even more severe than Europe). My point here is that the 1600s loom as a fulcrum period that created the pre-conditions, maybe, for the hyper colonial phase that began over a hundred years later. And it is worth thinking about the cultural reflections of all this, and in relation to this spatial elitism that Blaut describes.

Another aspect of the Thirty Years War was the orgy of witch hunting and burnings that occurred in Northern Europe (mostly) just preceding the start of the conflicts. This also, of course, is linked to the bubonic plague which engendered hysterical rumor mongering. The Lord Abbot of Fulda, Balthasar von Bernbach, personally oversaw the burning of 250 witches in a three month period. Overall, between 1450 and 1750 as many as 50,000 women were burned as witches in Catholic Europe (though Protestants burned them too, just not quite as many).

Arja Hyytiainen, photography.

“It has indeed lately come to Our ears, not without afflicting Us with bitter sorrow, that in some parts of Northern Germany, as well as in the provinces, townships, territories, districts, and dioceses of Mainz, Cologne, Tréves, Salzburg, and Bremen, many persons of both sexes, unmindful of their own salvation and straying from the Catholic Faith, have abandoned themselves to devils, incubi and succubi, and by their incantations, spells, conjurations, and other accursed charms and crafts, enormities and horrid offences, have slain infants yet in the mother’s womb, as also the offspring of cattle, have blasted the produce of the earth, the grapes of the vine, the fruits of the trees, nay, men and women, beasts of burthen, herd-beasts, as well as animals of other kinds, vineyards, orchards, meadows, pasture-land, corn, wheat, and all other cereals; these wretches furthermore afflict and torment men and women, beasts of burthen, herd-beasts, as well as animals of other kinds, with terrible and piteous pains and sore diseases, both internal and external; they hinder men from performing the sexual act and women from conceiving, whence husbands cannot know their wives nor wives receive their husbands…”

Pope Innocent VIII’s papal bull (1484)

The Reformation only intensified the witch hysteria. And the peak burning years were just prior to the Thirty Years War. There is a curious side bar of pyschoanalytic resonance in all this. Hephaestus or Loki or Vulcan, in all cases the satanic figure has a cloven hoof which he is unable to disguise. One can always tell by the sight of the deformed foot. Frederik Hall, in The Pedigree of the Devil, wrote: “Hephaestos, Vulcan and Loki, each lame from some deformity of foot, in time joined natures with the Pans and satyrs of the upper world; the lame sooty blacksmith donned their goatlike extremities of cloven hoofs, tail and horns; and the black dwarfs became uncouth ministers of this sooty, black, found fiend. If ever mortal man accepted the services of these cunning metalworkers, it was for some sinister purpose, and at a fearful price – no less than that of the soul itself, bartered away in a contract of blood, the emblem of life and the colour of fire.”

Postcard of ‘Nautch Girls’, Ceylon. Photographer unknown, date unknown.

One can feel all the connectives here, for the coven of North Berwick, in Scotland, in 1590, the charges against the women accused of witchcraft included the recitation of incantations to create a tempest and sink the boat of the King while he returned with his wife Anne from her native Denmark. The two bodies of the King, the vast terrors of the sea, and the power of the word — for even into the 16th century and later the charge of *heresy* was worse than murder. The sense of medievalism’s immersion in the non-tangible and ecstatic, the hallucinatory, is worth thinking about in terms of contemporary life and this trend toward a new feudalism. For it is not just in economic or socio economic terms that this revanchist feudalism occurs, but in the semi conscious or unconscious repressed material of the West. The archaic antiquarian memory traces of the courts of the Inquisition are as open psychic wounds today, much like the refusal to answer to slavery or genocide. Or to the orgy of animal killing that took place across the western U.S. in the 1800s.

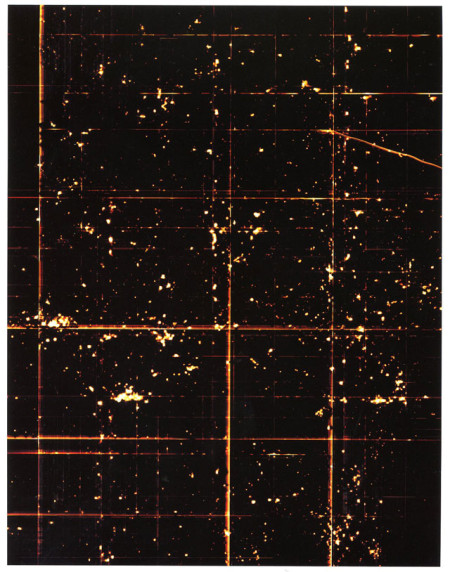

Marco Breuer

Today’s system of factory farming is a kind of substitute holocaust, subbing for the carnage of the great plains, and for various species these are daily repeated in semi-secret rituals of callous sadism. Trophy hunting is the exhibitionistic phallic symbol of masculine insecurity. The Inquisition on one level migrated to rape culture at football friendly Universities, to the military, while the Catholic Church retained the specialized realm of children. There developed a cultural denial of cruelty. One never sees the real horror of war. Caskets arrive in the secret of night, without photographers allowed. Death is officially non-existant, for all intents and purposes. And if one looks at the representations of death in popular culture what you see are cartoon and hence highly unrealistic depictions of death, even if often in great graphic detail, or one gets a kind of blankness where mortality is supposed to be.

The rise of colonialism was pushed by economic imperatives. As Blaut points out, in England for example, policy was shaped by men who had connections to the East India Company. The profit generated from conquest motivated legal and political legislation that served to increase that profit. By the late 1700s the religious component of spatial elitism had retreated a good deal. By the 19th century the rise of science and industrial planning was adapted to social arguments for this inside and outside idea. And that was basically the message that Europe and white people were advancing while the periphery was stagnating or declining. The religious art of the 19th century had become dry and empty, an echo chamber for colonial rationalizations. The medieval painting in comparison, looked at today, is hallucinatory and feverish, and also highly unrealistic. That idea of spatial realism arrived with colonial expansion. Blaut’s belief is that by 1900 the idea of expansion had given way to *normalcy*. There was no more space in which to expand, after all. Anthropological functionalism, a developing theory by the time of WW1 was really justification to keep unrest among the natives at bay. By granting a certain intrinsic value to the native populations, the paternalism of the West was able to congratulate itself on its benevolence.

Deleuze book on Bacon is a strange mix of revelatory insight and banality. Notwithstanding I think there questions asked in relationship to Bacon that are related to the received system of spatial elitism. For Bacon above perhaps all 20th century painters, was upsetting that sense of space.

Matthaus Merian (the Pope, 1621)

The classic colonial, meaning Western or European, model for building this global hierarchy is based on many factors, but the main ones were race, technological development, and logical debate. The most easily discounted is race at this point, but that has only intensified the insistence on technological development as a marker for Euro-centric models — the fetishizing of things like the stirrup or plow (as its known in the West). Many historians of the early 20th century argued that things like open field cultivation led to population growth, etc. Of course this ignores the fact that Africa and Asia both had open field cultivation in antiquity. It’s sort of pointless to go over the arguments, because none of them have substance. But today, there is a return of this kind of thinking, only in new garb. Jared Diamond is a highly popular version of this.

“[The] proximate factors behind Europe’s rise [are] its development of a merchant class, capitalism, and patent protection for inventions, its failure to develop absolute despots and crushing taxation, and its Graeco-Judeo-Christian tradition of empirical inquiry.”

Ulrich Ruckriem

Again, its white men and capitalism that paved the way for the paradise we see today. The fact is that Diamond is a deeply Orientalist thinker, and one clearly in need of education on Asian and middle eastern history. But this is the residue of the old racism of the British Empire that emphasized Oriental despotism and Muslim backwardness. Ben Barber is another populizer of the Imperialist world view with his book Jihand vs. McWorld. This is all well documented stuff, and Blaut in particular was highly productive, but Edward Said and Samir Amin are excellent corretives to the Nial Fergussons or Thomas Barnetts, or Diamonds, as exemplars of the resurgent white man historian. But my interest is aesthetics, and how these beliefs shaped the modern world image (and space), and also, more, how they are today returning. To do that, it is important to at least begin examining the origins of western taste.

“Reactions to the excesses of late baroque and the artificiality of French rococo were fired by the enthusiasm over the excavations at Herculaneum, Paestum, and Pompeii. In response to calls for a revival of the Greek architectural orders in the first half of the eighteenth century, David Le Roy published ‘Les ruines des plus beaux monuments de la Grèce’ (1758). The rule of ornament was challenged by the order of style. “

Vassilis Lambropoulos

The popularity of Hellenic culture in England, France, and perhaps most of all in Germany led to various treatments of that history, but also to aesthetic appropriations. As Lambropoulos points out, very few novels were set in ancient Greece because ‘bourgeois interiority’ found the landscape inhospitable. The actual philological studies, those of any real substance, seemed to take another hundred years following on the discovery of the Elgin marbles in 1807.

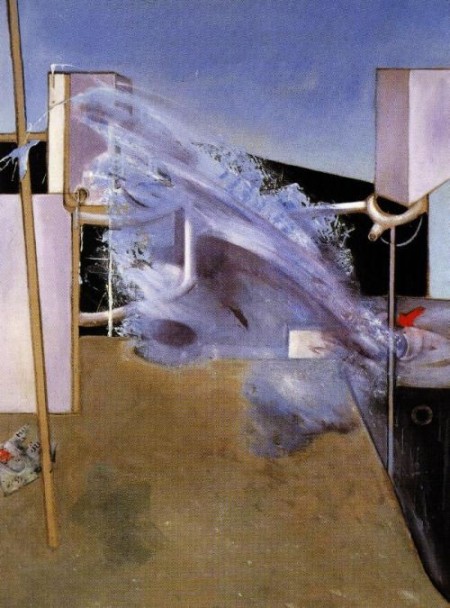

Francis Bacon

“German Hellenism both defined and served bourgeois cultural ideals in

a comprehensive way: it portrayed a land of pure Western descent; it countered

Pietist asceticism with Puritan stoicism; it provided an antidote to

French skepticism and British empiricism; it integrated leisure in Protestant

morality; it counterproposed democratic enjoyment to aristocratic

taste; it outlined the conditions of healthy individualism; and it ennobled

the project of a national culture.”

Vassilis Lambropoulos

The discipline of philology then had a double edged aspect. On the one hand there was a discovered suitable historical fantasy for Aryan superiority, and on the other a remarkable body of material that served, often, to exactly disrupt this desired vision. Joahan Wincklemann in the mid 1700s was the first to really look for the narrative thread that ran through all human culture. Benjamin was hugely influenced as it was Winckelmann who restored ideas of allegory and myth to importance. In a way it was Wincklemann who privileged the idea of art being a social phenomenon, one that revealed heretofore hidden aspects of both the political, ethical and the metaphysical. It was also Wincklemann who revived the concept of mimesis, and directly influenced Auerbach’s reading of ancient texts. A good deal of influence, aesthetically, is bound up with Hegel in all this, naturally. And while that exceeds a posting such as this, Teshale Tibebu has written of the buried racist underpinnings to Hegel, and that seems obvious enough really, with tentacles leading to Heidegger and others, but more relevant here is that there was a marked criticism of Wincklemann by many of his contemporaries who looked to re-instate a religious conformity (Puritan, Protestant, Lutheran) to Hellenic studies.

Jacopo Tinteretto (Creation of the Animals, 1551).

“Here, it is the Protestant Reformation that is the great mover of the

European juggernaut in its particularly compelling forms of the Lutheran

and Calvinist sects (but particularly the latter, for its transparently accumulationist

orientations) that transform values and social behaviors in more

“capitalist” directions by their insistence on parsimony, thrift, and productive

labor—but not prodigal consumption—as the new cardinal virtues to

establish true Christian worth on earth, if still in the eyes of an extraterrestrial

god. As such, it is “reformed” Christianity—in effect, a Europeanized

and modernized Christianity—that helps inculcate the standard mores of

capitalist rationality as the dominant ideal in in an entire people, this in itself

being the great European innovation in history.”

Rajani Kannepalli Kanth

Now, I return to Bacon here for a moment. In one sense, before looking at Delueze’ book, I feel personally sort of conflicted about Bacon. He most certainly had one great explosion of creativity that ran from 1946 through the fifties. He had one late masterpiece, Jet of Water, painted in 1988. There is no denying the force of this work, and yet by the 1960s, already, a quality of self parody was creeping into this work. And mostly nobody wanted to admit it. Later some did (Jerry Saltz for one) but with qualifications. Bacon’s subsequent popularity hints at something that began to feel cheap in that later work, a studied hesitant quality in the application of paint. When Hollywood directors love your work, it is worth considering what you might be doing wrong. Now, all that said, returning to Deleuze, who I think is correct in suggesting that Bacon instinctively found the destabilizing aspect of *space* as its represented in the post Industrial west.

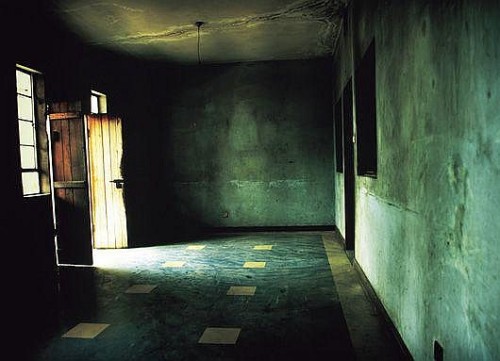

Zarina Bhimji, photography.

However, Deleuze is simply wrong about a number of things and I suspect this is just not an area he is particularly comfortable writing about. When he writes, for example; “Painting has neither a model to represent nor a story to narrate.” That’s just incorrect. It should take about twelve seconds to come up with twenty examples of narrative paintings. But as I have argued, even abstraction is narrative. Barnett Newman is narrative, so is Frankenthaler and so is Joe Goode. But we would have to dig more deeply into what is meant by *narrative*. But lets continue with Deleuze …

“Narration is the correlate of illustration. A story always slips into, or tends to slip

into, the space between two figures in order to animate the illustrated whole. Isolation is thus the simplest

means, necessary though not sufficient, to break with representation, to disrupt narration, to escape illustration,

to liberate the Figure: to stick to the fact.”

Well, that’s not right either. Isolation disrupts narration…escaping illustration? Maybe this is just a terrible translation, I don’t know. But no, an isolated figure can be illustration. And clearly can be narrative. I mean the entire genre of portraiture is in one sense predicated upon capturing something of the essence of the subject, and that essence I would think always implies a story. Not to mention Beckett (who oddly enough, or not, Deleuze cites) has a play in which all you have is a talking mouth in a black void. But that is a story, and has character. Isolation is an interesting idea, though. For one thing it returns the discussion to medieval painting in Europe. And up through the Renaissance, really. Religious intoxication was the de-centering mechanism for 14th and 15th century painters in Europe. In Tinteretto, who remains a particular favorite of mine, there is work so dotty and bizarre as to seem outside of almost all traditions. Now Deleuze mentions Tinteretto’s 1551 painting Creation of the Animals (which Deleuze says looks like the start of a race for the handicapped…[sic]). When Deleuze suggests that in Bacon the white lines that delineate space on the canvas, and creates this isolated figure, are comparable to Newman’s stripe — this isn’t right at all. That’s not what Newman is doing certainly.

*Cardinal Richelieu*, Prestige Minatures, for sale at toy stores near you.

“We must consider the special case of the scream. Why

does Bacon think of the scream as one of the highest

objects of painting? “Paint the scream…”. It is

not at all a matter of giving color to a particularly intense

sound. Music, for its part, is faced with the same task,

which is certainly not to render the scream harmonious,

but to establish a relationship between the sound of the

scream and the forces that sustain it.”

Deleuze

But see, the scream is expressed in form. In Blood Meridian the structure of the book, as someone said and I forget who, is a long scream. The scream is that which cannot be directly expressed. And Bacon didn’t really directly quite express it either, but therein perhaps lies the problem with Bacon. Now Deleuze also says that like Beckett, Bacon has created *indominatble* characters. This is a very odd idea, for either of them, but more for Bacon. But that word, that idea, indominatable. It is oddly sort of regressive, somehow. It mean invincible, unconquerable, and it smacks of a kitsch-like optimism. Walt Disney characters are indominatable. The real problem I think, in how Delueze approaches writing on culture is that everything becomes oddly a-historical.

“The social work of every individual in bourgeois society is mediated

through the principle of self.”

Horkheimer & Adorno

Joshua Reynolds (1779).

In contemporary Western society the spaces of urban life, and increasingly of suburban and rural, are containers with implied insides and outsides. This is so because the vision of the classes in control of constructing roads and bridges and housing complexes are those whose vision is a direct inheritance of colonizers. These are the new magistrates of the colony. I was thinking of Bertrand Tavernier’s 1981 film Coup de Torchon. For this was the vision of the colonizer who was wearing down. The black comedy of colonial blindness. So, to examine the cultural expressions, or artistic, of this vision, this gaze of the white European who imagines the world belongs to his culture, society and race, means seeing the ways in which the psychic deformations that allow this, and created it, work. For the Jared Diamond worldview is kitsch science. It is not greatly different from the science you might find in a Spielberg film. The line from the Thirty Years Wars, and witch burning and the Inquisition, to the appropriation of Hellenic culture (in Germany especially) to the critique of the Enlightenment, and to a gradual sense of culture and art that has separated itself from the public, from its audience, as a means to saving it — this line is direct. The epitaph resides in post WW2 art, the end of modernism and the birth of accomodation to the ruling class. The capitulation of labor to management in the 70s, the Reagan era of the 80s (and Thatcher), and finally the Clinton cartel and its press gang approach to NATO and client states around the planet. But the post script for modernist Uptopian promise was written by figures like Beckett and Genet, and Bacon, and a dozen others.

It is interesting that Spinoza lived from 1632 to 1677. Spinoza overlapped the Thirty Years War. Shakespeare stopped writing about 1610 or 1612. The Mandate of Heaven ended, the fall of the Ming Dynasty in 1644. The last vestiges of what was antiquarian ended around this time, the front edges of the Enlightenment began fifty years later perhaps. Colonialism not long after that, in the classical sense. The totalizing absolutist strategy of the Enlightenment was one inherently totalitarian (Horkheimer and Adorno), but also there was a kind of built in vanity. The major figures of Enlightenment though were not satisfied to be correctives. In visual arts what was lost was what is evident in that Tinteretto, or the above Carducho. And in a sense the best of modernism was always looking to recuperate that which was lost. The painters of that lostness would include Joshua Reynolds and John Singleton Copley. I am being simplistic a bit, but Reynolds portraits of children suggest prophetically the future colonial magistrate or Memsaab of the Raj.

Abelardo Morrell, photography (camera obscura).

The end of feudalism merged with a societal set of questions having to with *effectiveness*. Maybe it was simply that logic was now being applied to notions of how to govern.

“How to govern oneself, how to be governed, how to govern others, how to accept him who is to govern us, how to become the best possible governor, etc. I think all these problems, in their multiplicity and intensity, are characteristic of the 16th century.”

Foucault

I think the post modern epoch is marked most by an erosion of Hermeneutics, actually. There is little reading, and even less to read. There is only sort of fragmentary scanning by the human optical scanner. New Macbooks advertise high resolution screens with *retina display*. A marketing term but an effective one. For it has some theoretical meaning as that threshold beyond which the human eye cant make out individual pixels. The ethical arguments of the 16th century were subsumed by the Enlightenment hubris. My sense of space travel and moon landings from fifty years ago is that with the kistch dmystification of heaven, or the cosmos, the return to earth was to a rebooted earth that had jettisoned the last vestiges of theoretical moral ambivalence. The space race somehow made Ayn Rand seem sensible. Looking back at earth, in *photographs*, subtextually validated photographic evidence all over again. Man and progress were clear winners. Nobody saw a Kenyan moon landing, or Mali moon landing or Albanian moon landing. White heroism, white know-how. Progress was increasingly a-historical. Progress was an event. A gadget. Winners had them, losers did not. So history seemed increasingly to resemble one’s own personal success at the office or factory. Or on the playing field. Expand, grow, and win.

The fact that Kenya and Mali were colonized and Albania occupied, was never a factor in this shiny white model for world history.

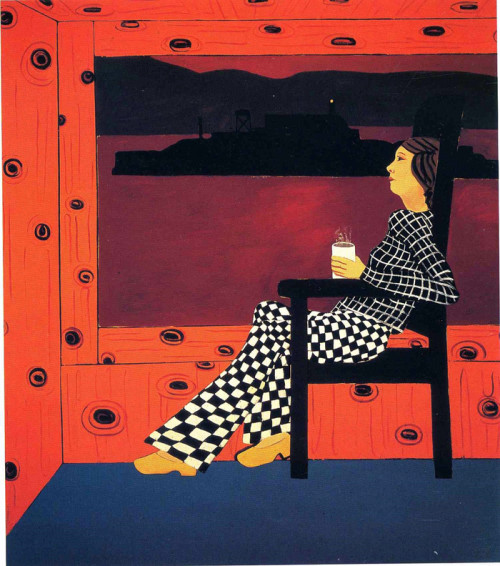

Joan Brown

“While originally interpretation signaled the rebellion

of exegesis against dogma and ritual, five centuries later, in order to

insure the survival of the bourgeois dominion, it allies itself with the law

and a new regime of regulations modeled on contemplative, observant consumption.”

Vassilis Lambropoulos

The economic factors that drove colonialism were, I suspect, secondary to the civilizing mission of white Europe. Today, the landscape of western cities all echo the plantation. That vision, that gaze of the colonizer, lies behind almost all actual building, but also resides in ideas of appropriation in culture. Marketing and advertising are the outgrowth of this gaze. Psychoanalysis suggested the dark and hidden toxicity in individuals, and the mechanisms of compensation and projection, but such ideas were shoved to the side.

“Progress required a shining standard: Europe provided its own modernist

institutions as such a gleaming benchmark. It required a touchstone, and a

materialist ideology delivered continuing, unstinted capital accumulation as

synonymous with the welfare of this world and its peoples. It required an enduring

merit badge of abject failure to set off its own supernal success in high relief,

and so the non-European “Other” was duly wrapped in the black flag of the

permanent disgrace of (an ill-conceived and miscalculated) underachievement.”

Rajani Kannepalli Kanth

Chris Brodahl

The bourgeois self image only worked in a set of hierarchical markers, and if those markers required erasing the history of Asia and Africa and of Native American peoples, well, that was just fine. The gaze of the plantation owner is the gaze of the security guard. It is the gaze of the panopticon, and of the zoo keeper. The evolution of ideas of culture, the ones that seemed to end with modernism also promised a resistance to these assumptions. But such resistance was, paradoxically perhaps, only possible at the end game of this evolution. In a sense that was Adorno and Horkheimer’s critique of the Enlightenment. If the conquests of colonial expansion needed justifications that reinforced European superiority and paternalism, the same is true today in contemporary science. For most research is simply a quest (conquest) for economic discoveries. Science is about exploitation. And, it uniformly adjusts itself to that gaze of the plantation owner.

The political model, a visual/spatial model in which a third world exists outside the core first world, is of course pure metaphor. But it also reductive, and suggests another quality of late Capitalism; that of distillation. So much of contemporary cultural writing is a diluted and distilled description of what are, really, complex problems. Politics is distilled down to electoral theatre. And electoral theatre is further distilled down to a two party carnival. One of Kanth’s observations is that the third world, the subaltern, is the feminine. The first world is aggressive and dominating, or male. The mass culture of Hollywood is now assigning women roles that demonstate how good they are at imitating men. Hillary Clinton is the horrifying culmination of this process. But more, the distillation occurs alongside this, as does the self congratulation, for narrative is increasingly one dimensional and missing any subtext. The phenomenon of people pretending to have Aspergers is a reflection of psychic processing trained to see the distilled and simplified as easiest and most functional version of reality to which to ascribe.

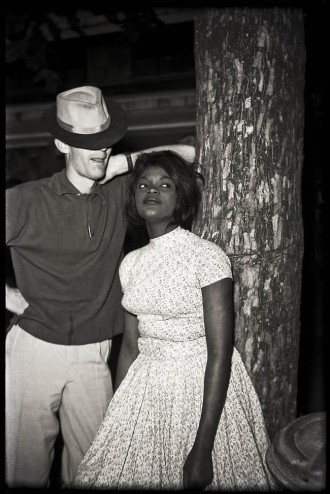

Depara. Photography. (Kinshasa -1955-1965).

“If we look at the “picture” of hysteria that was formed in the nineteenth century, in psychiatry and elsewhere, we find a number of features that have continually animated Bacon’s bodies.”

Gilles Deleuze

This is a telling comment. For it is where the value of Bacon resides, in his X-ray of bourgeois sensibility, the repressions and sublimations. If medieval art expressed a gaze unfettered by Enlightenment notions of progress and domination, the madness is religious, and it accepts a kind of hallucinatory space. And that space still is linked to the Dionysian space of revelation. It is space that opens to possibilities of hidden or secret meaning, in which history is embedded. Bacon was transcribing something prophetic in landscapes in which hiding meant hiding from surveillance. It is the inside of a securitized landscape of the human. In a way Bacon feels very close to Artaud. Something Deleuze recognized as well. The manicured reality of much 19th century painting, and a good deal of later 18th as well, was the decorous picture of sanctioned values of bourgeois society. And it led to, in the U.S. artists like Winslow Homer or John Cheever. The modernism that sought autonomy by negation was recuperating, in some fashion, the work of pre modern artists. There is a delicate line here though, for nostalgia is an insidious affliction of work that only looked backward. Today, there is a cleansing, or rather re-cleansing of the past that is exemplified in historians like Jared Diamond. One that sees no commodification of desire, or fetishizing of gratification. This is acceptance and promotion of stunted emotional life, or shrunken experience. The gaze of the owner is always watching. Buried within all zombie films today is a furtive longing for things lost due modernization. What those things are remain only dimly grasped, if at all. But the feeling remains…we have missed something. It cannot be reclaimed. For the place where society as a whole, maybe just Western society as a whole, has reached, today, is one where those things are lost forever.

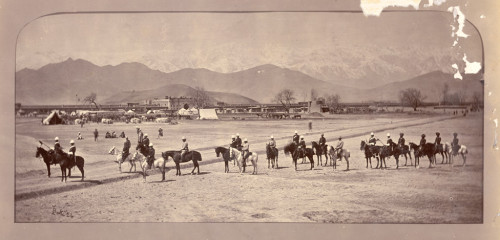

John Burke, photography. (Sherpur, 1879).

In a society in which political theatre is hardly even disguised anymore, the fact of a Donald Trump even appearing as a faux candidate, is worth noting. Hillary is the next president, and Trump only a distraction, but he is not an insignificant distraction for he echos Berlusconi and Mussolini both. Sartre said that ‘anti semitism was the poor man’s snobbery’. Trump’s biggest supporters are the bottom rungs of white collar workers. Trump is the conditioning factor for the new fascism. His very homeliness and vulgarity is even reminiscent of Hitler to some degree. He is the cartoon fascist orator, a George Wallace of post modernism. But he is also visibly submissive in his mannerisms and theatrical comb-over, the vaguely feminine and grotesque orange fetish of the masochist. What is lost is lost amid this spectacle of self parody. Hillary is the former Goldwater girl now viciously spiteful and resentful. A clucking parody of Barbara Bush, in many respects. Contemptuous of the underclass; whose visage now feels like one best suited to the executioner’s hood. The burning of witches was that sickness born of metaphor becoming drained and then propped up as real. A society that confused levels of reality, as Bly once remarked. The orgy of violence that was the Inquisition is replicated now in militarized police forces across the U.S., and by staggering numbers of white men bent on making the only mark on the world they can imagine. Killing. Randomly or with the prospectus for a plan. But kill nonetheless. When there are no buffalo left to kill, then kill each other. Anti depressants, video games, constant desublimation at the hands of an insane ruling class who themselves have not much purchase on reality — and the voices of men like Trump — millionaire cartoon submissive — asking only to worship the already dead project of Western modernity.

Speak Your Mind