Leonard Missone, photography. 1938.

“Art is permitted to survive only if it renounces the right to be different, and integrates itself into the omnipotent realm of the profane.”

Theodor Adorno

“No matter how artful the photographer, no matter how carefully posed

his subject, the beholder feels an irresistible urge to search such a

picture for the tiny spark of contingency, of the Here and Now, with

which reality has so to speak seared the subject, to find the

inconspicuous spot where in the immediacy of that long-forgotten

moment the future subsists so eloquently that we looking back may

rediscover it.”

Walter Benjamin

“In Benjamin’s view, certain photographs have an aura, whereas even a painting by Rembrandt loses its aura in the age of

mechanical reproduction.”

Douglas Crimp

Benjamin’s notion of ‘aura’ is an historical quality of subjectivity, not something embedded in an artwork. The difference, however, is often very subtle (and at other times rather clear). Benjamin wrote…“The auratic object is at once something unique, something with the authority of authenticity and something which carries a “testimony to the history it has experienced.” Benjamin saw art and artifact in terms of his own rather personal Kabalistic memory, and his place in an historical continuum. For how Benjamin looked at artworks, whether in achives or museums, or galleries, was as a visitor from the past. From history, or rather History. For History loomed auratic itself. And I have said, echoing someone else, that the auratic itself was auratic. What Benjamin was concerned with, really, was in many ways what the majority of Frankfurt School thinkers were concerned with; and this is that the very structure of human experience was changing …and changing more dramatically than possibly in any period in history before. That the emergence of radical changes in industry and then technology, under the umbrella of Capitalism, and driven in a sense by Capital as well, was altering both how people viewed the world around them, but more, and more illusive, how the world revealed itself to the gaze of man.

And in a sense this is a crucial aspect of all aesthetic discussion. Or, should be. That the gaze of the subject is met by other gazes, and is also met with Nature, and all that implies. That Nature gazes back. As an example, when Benjamin wrote on Sander’s and Atget’s photographs, it is never fully clear if what he means by *aura* is something that emerges from within those people being photographed, or is it merely the technical residue left in and on the image. Those being photographed in Sander’s many portraits, were people acutely aware of their own class and its activation historically. The emergent class characteristics are what is meant by *aura*? Perhaps, to a degree.

Milo Newman, photography.

Benjamin’s famous essay Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction describes a very different *aura* than the one he described in his earlier Little History of Photography. The earlier piece of Benjamin’s is far less quoted than the later. I think the earlier essay is probably the better and more important of the two. What I wanted to get at here is that what Benjamin calls *aura* in that earlier essay is something like a social ritual that is represented by some means in the artwork. The aura in Sander’s portraits, or Blossfeldt, or Felix Nadar, say, is one that cannot be de-linked from the social dynamic that involves photographer and subject. However, in those photos in which no people appear, this sense of ritual is still present, only it is buried somehow. The burial is, in one sense, what the photo is about. And this is true well into the 20th century I think. It changes after WW2, and maybe it was changing well before that. But clearly by the 1950s it is very hard to find photographs that capture that same quality of ritual. What replaces it, however, in the best photographic work from the 50s, is a sense of annulment. That is certainly what I see in the New Topographic photographers — a quality of transcribing the loss of the social contract. And more, the loss of community. The loss of that elusive tension between embodied in social ritual.

A recent poll found that 30% of Americans were in favor of bombing a country called Agrabah. Except this is a fictional country found in Disney’s Aladin cartoon. So, appearance matters a great deal to this new sub-literate demographic of white America, and it speaks to, of course, a rabid desire to punish and to kill.

Felix Nadar, photographer. 1910.

“Language communicates the linguistic being of things. The clearest manifestation of this being, however, is language itself. The answer to the question “What does language communicate?” is therefore “All language communicates itself.”

Walter Benjamin

On Language

The seeds of this irrational desire to kill are found in the founding Puritan culture of the American colonies, but the secondary shift, I think, came after WW2. The age of marketing and advertising, that documented by Adam Curtis (himself a very strange and crypto reactionary) in Century of the Self. Whatever one makes of Curtis, really, that documentary touches on and articulates very cogently the machinery of mass delusion. The deeper significance of wanting to bomb a fictional cartoon country lies in the fact that the majority of those who so want to bomb don’t care if it’s imaginary. Tell them this place doesn’t exist and they wouldn’t care. Bomb it anyway. And this is at least partly because they are quite accustomed to a reality in which questions of material existence no longer matter. Evidence is only what you want. Desire IS evidence. What one sees in the faces Sander photographed is something that has gradually but inextricably gone missing in Western societies over the last one hundred years. This is certainly only my subjective sense of it, but then that is all I have to trust, finally. That ritual of social recognition, the sense of awareness in the subject, both as photographic subject and as photographer, has now migrated to a realm of narcissistic annulment. The cancelled self.

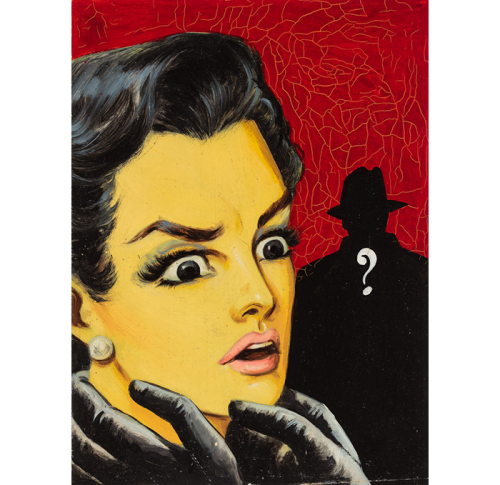

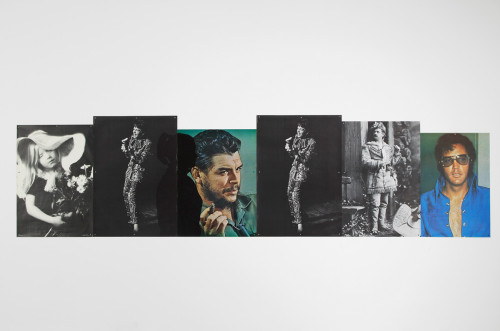

Mexican Pulp Illustration, late 60s. Oil tempera on illustration board. (Ricco Maresca Gallery).

The idea of photography has no doubt changed significantly in the digital age. But I often get the feeling that this change is less all inclusive than is often described. Or maybe, rather, that what has changed has more to do with the oppressive nature of daily life for most people, and a sort of stealth exploitation and manipulation, and that image is a tool in the machinery of domination — often anyway, very often, and so there are a whole litany of conditions and situations, psychologically, that are the direct result of fifty or sixty years of mass capitalism in the techno West. The images, the withering of aura, and of deep meaning, or curiosity overall, is not something caused by technology, it is caused by an ever deepening coercive dynamic between workers and a ruthless management class, proprietor class, that sees only its own ownership as of value. That is its own madness, but more on that below, for now the sense of auratic atrophy is worth examining in how artworks are compromised, or fail to register their intent, and in general are objects of such scorn.

Diarmuid Costello has a good piece on Benjamin and aura, and he points out that for Benjamin, early on anyway, film was inimical to the auratic. It forclosed the possibility, and was more attuned, actually, to being a sort of psychic boot camp for adjusting to 20th century urban life. One wonders what Benjamin would make of 21st century New York or Lagos or Tokyo. Benjamin saw film lacking that quality of invitation found in painting — that its nature was to resist contemplation. I am not sure I agree, not entirely anyway. In a way there is a need in the audience, the viewer, to re-calibrate that contemplation. It is not the contemplative distance of the bourgeoisie with the spare time to so indulge, but the experience of film I think can still be auratic, but this will return things to trying to define that word. The point right here is that film, moving pictures, were born of seaside amusement parks, and have a built in quality of shock (per Benjamin). But the audience today, raised on a culture that has denied almost everyone the space for contemplation, the film-as-art discourse seems almost always (short of some of Cahiers, and a good deal of Positif) to increasingly see film as broken into various class demarkated sub-groupings, carefully vetted to flatter their specific demographic. Film, as a studio business, and today one that is intimately tied to D.C. power brokers and the U.S. State Department, exists in a strange semi schizoid realm of purported faux populist seriousness, and craven cartoon stupidity, the titillation and violence porn that is now so normalized that almost nobody takes notice. We are surely at the end of the emotional fatigue spectrum for all this stuff.

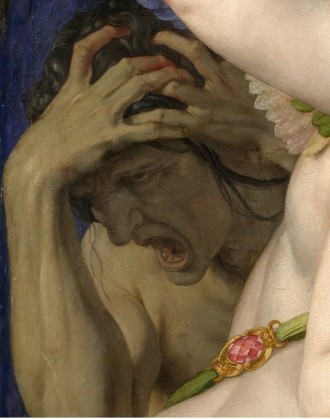

Bronzino (Allegory with Venus and Cupid, detail) 1546.

“Artworks, as Adorno remarks, ‘open their eyes’. At their

most compelling, works of art look back at us, appearing to exhibit a subjectivity of

their own, a subjectivity capable of putting us in question. Now, if this is what is

disappearing as a result of the transformations in the structure of experience that

Benjamin is tracking in terms of the withering of aura, then what is disappearing is

not only our ability to appreciate the aura of a Rembrandt painting in the age of

technical reproducibility, as Crimp suggests, but our capacity to perceive or respect

the uniqueness, difference or distance of any object of experience whatsoever –

including that of other persons.”

Diarmuid Costello

There is in mass culture today, in film and TV, but also in art photography or installation and even in theatre to a degree, a normalizing of blankness, loss of affect. In a way the precursors to this included Vogue fashion shoots with anorexic blank models (mimicking to some degree those qualities associated with the starving and malnourished — and which fact is worth noting as a fractyl of the general overriding appropriation of all that is left to the poor, their body), and Chiat Day advertising, commercials mostly, and from another angle the masked expressionless robot or unitard super heroes of DC and Marvell comics. The insect face of all masked aliens — from Flash Gordon to Star Wars, the hidden, it is implied, hides nothing. The mask hides nothing, really, only more masks. It hides identity, and identity increasingly comes under interrogation. The gas masks of WW1 soldiers, as Traverso pointed out, became Doctor Fate, The Phantom, Arrow, and the quite directly related Sandman, who not only shared the name of the E.T.A. Hoffman’s short story (which Freud incorporated into his uncanny essay) but who wears, in fact, literally a gas mask. By the forties one had characters such as Black Marvel, Hourman, Quicksilver, Green Lantern, Doctor Mid-Night, etc. On to the fifties and a dozen more. The vast majority employed masks and most were hiding their daytime identities. Throughout this sub phylum of popular culture there was an erosion of expression. It is perhaps worth tracing the evolution of the representation of those daytime identities (Clark Kent et al). My sense is that increasingly the day job is treated with greater contempt today, and of course the transormation into mutant crime fighter requires less psychic or emotional cost. This was the telling quality of Gothic monsters found in 19th century novels, the trade off was always at least semi tragic. Today, even when, for example in Arrow, there is an effort made to explore the cost, both biological, ethical and emotional, the end result is one of a general acceptance of cancelled personality. The last popular hero who had a tragic dimension, oddly enough, was the 1970s Incredible Hulk TV show with Bill Bixby, created by Kenneth Johnson, in which Dr Bruce Banner is forever condemned to wander alone in search the elusive real killer. His transformation into the *Hulk* is both a source of shame and personal suffering, but it haunts him as moral stigma. It is the last time I can recall the character with special powers playing a secondary role to the original *ordinary* man or woman.

Edmund Clark, photography. (Abu Salim Prison, Tripoli. US and UK rendition site).

Now this relates to Benjamin’s notion of *aura* because as Costello says, a loss of discrimination and difference is pervasive now, and it is another aspect of a perceptual apparatus that resembles autism. Sigrid Weigel correctly noted that everything from Benjamin on film and photography has been banalized because it is interpreted through a topos of reproducibility. Weigel, like Costello, sees Benjamin’s auratic declarations having a far more complex and nuanced meaning. And the real point, I think, for Benjamin was the psychological and social implications for *seeing*. For legibility. Weigel suggests Benjamin saw two profound results coming out of technologically reproduced images; the shock and the detail. The detail is implicated in Freudian constructs of consciousness, with the *discovery* of the previously unseen. But behind both shock and detail are psychoanalytic and political assumptions. For aesthetics here are inextricably tied to structures of social life.

“…media theory in Benjamin’s sense always also includes the history of media.”

Sigrid Weigel

Loretta Lux

Benjamin was concerned with *image*, as he defined it. And with how image subsumed simple form and content paradigms. For Benjamin was interested in how image and writing came to be seen as separate rather than closely related systems; the grapheme (Flusser) and the image were both pictographic scripts. In other words, per Weigel, one cannot really understand the concept of aura without recourse to an epistemic history of recording systems. And this leads directly to allegory and language. And this leads back to detail and shock. And perhaps especially, I think, to detail. In Benjamin’s early work on the German Mourning play, he writes of the “life of the detail”. He also wrote that “in the last analysis structure and detail are always historically charged.” When Benjamin writes of the monad, that every idea contains the image of the world, he is echoing Adorno’s ideas on art, on the transcription of the history of human suffering. The detail then, in photography, arose in a sort of opposition to European painting which, almost ideologically, viewed one of the roles of the painter to be eliminating the useless and superfluous detail. Benjamin posited what he called ‘an optical unconscious’. It is interesting that the example Benjamin used in his early essay on photography, was ‘slow motion’, which is actually a property of film, not photography. But it also references Muybridge and others who were creating chronophotographic projects aligned with science. It is important in that light to remember Benjamin rejected the idea that photography was there to improve upon the human eye.

The optical unconscious is related to Freud, but also distinct. A technological device is revealing previously unknown worlds. Hubertus Von Amelunxen wrote that enlargement (another property related to detail) resulted in a dissolution of conventional systems of encoding — graphemic signs become scriptorial pictures (paraphrased by Weigel). The detail reveals the hidden, and this corresponds to psychoanalytic discoveries, and links to the rise in detective fiction as well as transforming social trust in the idea of the eye witness and evidence overall. But Benjamin saw *something* else and he used the word *something* in fact when he wrote of David Octavius Hill’s photographs.

“We encounter something new and strange…{ } something that goes beyond testimony…something that cannot be silenced…”

Steve Sabella, photography.

But Benjamin was writing of early photography. And that meant, certainly in terms of human subjects, what would now be considered an unnatural precondition. Long exposure time meant the subject could not move. This created an uncanny quality that noticeably lessened as optical technology progressed. Benjamin saw in Atget’s photos something significant in terms of the auratic. There was a shift in attitude on the part of the photographer. What Weigel calls *criminalistics*. And Benjamin then made his now famous comment that Atget’s photographs look like a crime scene. What is less quoted is the rest of that comment…“But isnt every square inch of our cities a crime scene?”

Interestingly Benjamin, in the second Paris Letter cited Courbet’s paintings are precursors to the optical unconscious, especially The Wave. And this is to be seen, I think, in the light of another remark of Benjamin’s; “The illiteracy of the future, someone has said, will be ignorance not of reading or writing, but of photography.”

Jean-Luc Mylane, photography.

The implication is really pretty far reaching, for it re-introduces this idea of a visual grammar, of the legibility of images. Graeme Gilloch notes that for Benjamin, photography creates gesture. By virtue of the fragmenting of motion (meaning Muybridge primarily) certain previously unseen (consciously) movements are discovered. When discussing Atget, Benjamin noted an absence of atmosphere. This is linked to a discovery of gesture, to the secret of motion. And revealing this secret goes toward killing atmosphere. Except it doesn’t really, not completely. The illiteracy of the future then is one in which a billion selfies has gone toward a new illegibility of image. The loss of aura has some connection to technical advancements, but it cannot really account for the titanic level of banality that image serves today. For today, the photographer, the casual photographer, is creating image in the service of erasure. Here is a long quote from a review of Palestinian photographer Steve Sabella…by Kamal Boulatta, who is examining, really, the restoration of secrecy in artists like Sabella:

“…in Sugimoto’s hours-long exposure of

photographing the sea at different times of day and

night, it is through the infinite tones between white

and black that the mystery of the ancient blue surges

to embrace all bodies of water since time began. Acting

like a subliminal connotation of the yin and the

yang, the simplicity of dividing his image vertically

with the horizon line into sky and sea may share

compositional affinities with Mark Rothko’s last

paintings. But the fathomless void in Sugimoto’s

world of air and water invites a meditative reflection

that memorializes the life of the photographer,

who first saw the light by Japan’s sea. In contrast,

it is sheer despair that settles in Rothko’s monotonic

paintings executed the year preceding his suicide.”

Kamal Boulatta

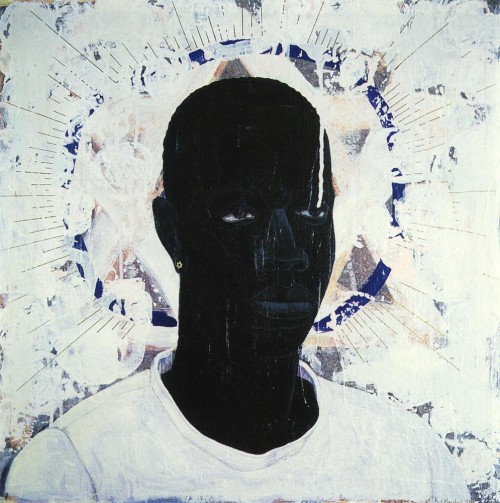

Kerry James Marshall

Benjamin wrote of the ‘spark of contingency’, a moment of recognition or reciprocity wherein the viewer in the here and now is fleetingly identical with and in the then and there. In which the photograph looks back at us. The auratic then is not dependent upon any particular stage in technical evolution, any particular skill. The loss of aura was the result of a loss of taste. It was removed ad hoc by commercial interests. The billboard of the Marlboro Man is a-auratic because the image is strangled by the commodity form. Nothing hidden is revealed. In fact, much that is there is being hidden. In that era of photography, from the mid 19th century through the early 20th century, objects exist in photographs with a weight that resists duplication. In good measure this is because at this stage of Capitalism the mass reproduction of commodities had not yet seeped into our psyches. The photographer was seeking to see something. The optical unconscious, however that is really formulated, was still a process in which discovery took place. Today, the cycling of image is so rapid, and of such scale, that difference is at best implied, and usually is not even a consideration. The viewer no longer looks to find the unique, but rather the novel, or innovative. The false difference is only a stage in pathological repetition of both image and narrative.

The age of photoshopping has meant that verification is a moot point. The illiteracy of image is indistinguishable from all illiteracy. A failure to read, the ability to read being lost, has left a populace with a shrunken sense of story, but also of place and memory and more, of self. The image of one’s self reproduced in 14 jillion selfies taken every day is a process of erasure. The contemporary world of TV is one of such abject blindness that you could show the president eating an electric turtle and then exploding and there would be about as much response in social media as you find when Justin Bieber gets a new haircut.

“The greater the shock factor in particular impressions, the more vigilant

consciousness has to be in screening stimuli; the more efficiently it does so,

the less these impressions enter experience [Erfahrung], and the more they

correspond to the concept of isolated experience [Erlebnis]. Perhaps the

special achievement of shock defense is the way it assigns an incident a

precise point in time in consciousness at the cost of the integrity of the

incident’s contents. This would be a peak achievement of the intellect; it

would turn the incident into an isolated experience [Erlebnis].”

Walter Benjamin

August Sander, photography.

Shock and detail are closely attached. And in fact, I think, can almost not be really discussed separately. But shock is easier to examine in terms of cinema. And certainly Benjamin was prescient in discussing the collective effects. As Costello puts it; “When this becomes the dominant form of experience, the present is increasingly cut adrift from the past, because it is no longer assimilated to past experiences. As a result, the collective store of past experience is no longer transmitted, along with present experience, to the future.” The production of forgetting.

The problem with Benjamin’s concept of *aura* is that at some level it starts to feel almost irrelevant to other factors. The auratic is only there as an experience of self awareness, in a sense. But of a specific sort of self awareness that occurs as part of a social relationship — mediated by the artwork. As the individual begins to fragment and dissolve under late capital, there is of course going to be a loss of aura. The auratic is inimical to the ruthless more powerful super-ego. But great art retains something auratic anyway, almost against its own negation. The reification of society, the onslaught of hyper marketing, and now the manipulations of various social media platforms all work toward control of perception, but also all function in various ways as propaganda. What remains important, I think, is that within this concept of aura there resides very significant ideas about ideology, and memory. One key idea here is to what degree the technical inventions associated with photography and later with cinema were the logical outcome of Industrial society, the expression of latent desires for reproduction of certain representations. Does Fordist production design become internalized and projected outward? Or is it internalized and split somehow? The rise of anxiety in the contemporary world is, for example, a product of the acute coercion of Capitalism and Imperialism. It is not natural to be anxious all the time. Even if conflict is foundational in human psychic development, which I suspect it is, the fact is that a sane humanistic compassionate social setting would allow for resolution of such fears and rivalry, rather than their exasperation. But there is something else in Benjamin, and in the auratic concept, and this feels to be something becoming more common. And that is that the reduction of experience, the reduced capacity in many to differentiate, to distinguish the fraudulent from the authentic, has migrated from a being the result of manipulation, to be a source point of desire. The desire for blindness, for illiteracy, is growing I think. There is a huge number of people in the West today who do not want to know more than they know already. And this is no less true in academia then it is in auto repair shops or banks. If one reads, for example, Weigel’s very good book, mostly, on Benjamin, there is still a section that employs the Saddam Hussain narrative as an exmple of Benjamin’s critique of violence. Putting aside the interpretation of Benjamin on violence, the fact that Weigel so little questions the propaganda of the U.S., and so dutifully reads the invasion of Iraq in terms that would not be out of place at the N.Y. Times is pretty amazing.

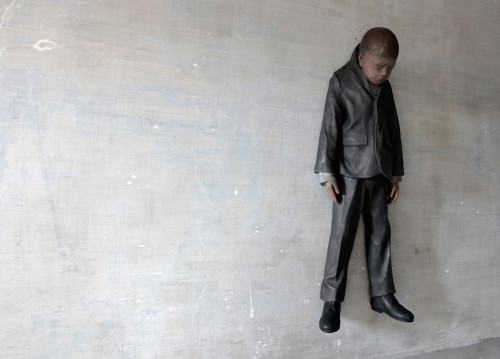

Sofie Muller

I had this conversation with a friend this week; the curious lapses of this sort that one finds in otherwise very bright people. I know smart people, whatever I mean by that, who think Pussy Riot is great. Who adore writers like Timothy Garton Ash, or artists like Rachel Kushner. At some point there are actual questions in such usually discarded observations, dismissed with bromides about subjectivity etc. But no, in fact, if you cant grasp, for example, that Alfredo Jaar’s work is colonial and racist, then there is a problem, and it is one that is not entirely unrelated to the auratic. Because it seems to me that one of the front edges of this continuum of illegibility is that of class, and of privilege. White people find it very appealing to lose sight of their own privilege. The rich, or affluent anyway, find it appealing to *forget* class distinction. Many men find it convenient to forget misogyny in their own relationships. One kind of blindness is the tendency to generalize and make abstract that which is not. There is a dual contradictory tendency in some of this; one side finds everything has always been this way, while at the same time inhabiting the other side that yearns for and validates novelty and innovation. Much cultural criticism has this sound to it, the mushy image free jargon of university programs in the humanities, and another sound is the one I associate with places like Salon or Vox or VICE. Rachel Kushner, I can attest to this, has been described at the least three times in major publications as a *kick ass* writer. These free floating descriptions are not surprising in a sense. Kushner is white, a woman, graduate of an elite University (Berkeley) and so ticks off a lot of boxes for appropriately being labled *kick ass*. My point, (and of course Kushner is an easy target) is that for the educated classes today there is a specific sort of cultural blindness, one that bleeds into politics by default. I have heard Netanyahu called a rock star, I have heard Yanis Varoufakis called a rock star ‘twice’, and Hillary Clinton is repeatedly referred to as a hard ass (as in compliment). I read recently, in a sort of review of some pop singer, that she was totally empty, and this wasn’t an insult.

Masahisa Fukase, photo by Kazuoki Nozawa

In other words, critical judgement is all but gone. It is buried beneath figurative mounds of academic jargon, or it is buried beneath figurative mounds of hipster attitude-prose. There is of course, and has been now for twenty five years, a marked ageism at work in media and culture. The result is a strange quality of intellectual vertigo brought on by reading a lot of writing by humans under thirty years of age. And this connects aura with another concept embedded within; ‘trace’. The distinction is really that aura involves a permanent presence. The trace does not, but rather is the mark of what has already left. I believe that the way Benjamin describes ‘traces’ is very close to my idea on theatre, on that something that has left the second the curtain raises or lights come on. Benjamin’s ‘trace’ is a residue left behind. In theatre, the trace is more an active escaping element — itself very auratic. For the auratic is invisible, illegible. The trace is a ‘something’, enough of a thing to be identified as belonging to what is now gone. All of this is, as Gilloch writes…“The trace which bears witness to the dissolution of the object is intimately connected to the transient, ruinous realm of allegorical expression.”

The auratic and its quality of illegiblity is a projection of historical knowledge, in a sense. Of tradition. Benjamin though, at some point, writes as if aura IS trace. Or he does so in cases where the auratic is destined to disappear. And this is only possible when significant artworks reach the level of the necessary. Benjamin calls this a ‘possession’. And it returns the discussion — for Benjamin — to the origins of culture in magical ritual. After the Renaissance, the cultic waned to be replaced with a fethishized ideal of beauty. I am not sure this is quite right, but what I do think is true, and hugely important today, is that art and culture by virtue of their societal marginalization are no longer capable, it seems, of reaching the level of allegory or even ritual. Contemporary art is awash in empty ersatz ritual. This is where Adorno is important because he saw in certain images, and in certain artworks, a built in critical expression of a world that was in the process of marginalizing all culture. Disenchantment. For the area where Benjamin seems contradictory is in the very idea of reproducibility. Whether he really believed technological reproduction trended toward emancipation, the every idea of aura getting lost was itself lost in the de politicized descriptions of that process of waning. In other words, the reality is that the auratic simply migrated. There are countless photographer/artists today that are keenly auratic. Awoiska Van der Molen, Sugimoto, Fukase certainly, and even some of Ruff and Hofer and Von Rauch, and Sam Laughlin. There are many others. And it is hugely important to know why Von Rauch for example is qualitatively different than a Greg Crewsdon. In the same way it is important to know why Bresson is superior to Lynch. The ability to mass produce only points toward a heightened importance in the context or space of presentation. The context is now auratic. It is the exhibition value become auratic. Now of course the system of exploitation and profit senses in that uncanny way the weakness or frailty of this exhibition aura and adjusts on the fly. Still, the sense of of space becomes an important question and one that leads to questions of architecture. The potential for restoring something of an allegorical resonance is found in how space is created, a space to experience the illegible.

Julie Watchtel

Adorno recognized the latent issues in Benjamin’s ideas on aura. And Siegfried Kracauer was a far more nuanced thinker on the subject of film. There is another huge topic begged by questions of reproducability, and it is one I want to discuss in another posting. The idea of the camera and its relationship to the audience. What happens to performance when it is for the camera? Just how important is it, really, that scenes in film are edited to creates illusions of continuity? Perhaps less than many media theorists would have one believe. For the viewer engages in a process of mimesis, of re-narration, and those gaps are his own as much as the filmmaker. A painter is not subject to such interrogation because there is a comfortable bourgeois image of what painter and painting are and do. Sculptures are not talked of in terms of discontinuity, and yet there is a narration to them as I believe there is to all artworks. The technical is now fetishized to an extreme degree I think. And some of this has to do with very prosaic notions of reality, notions which are not normally even considered, really. Part of this is linked to a regressive view of abstraction itself. And much of this is the product of U.S. marketing power.

“Yet at the same time, photography reveals in this material physiognomic aspects, image worlds, which dwell in the smallest things – meaningful yet covert enough to find a hiding place in waking dreams, but which, enlarged and capable of formulation, make the difference between technology and magic visible as a thoroughly historical variable.”

Walter Benjamin

Little History of Photography

Whitney Hubbs, photography.

The detail and the shock. Optical technology (the camera) changed how the world was seen, but it changed it by creating a new space for mimetic engagement. The detail, the enlargement, and later in film things like slow motion — but this was partly (and is partly) subsumed by advanced capital, and mediated in the West by an intensification of Imperialistic militarism. A culture under duress, coerced and oppressed, is not guilty of permitting the withering of aura, but rather is itself the victim of a whole complex of numbing and psychological erasure.

Mika Elo writes:

“…Benjamin notes that semblance and play have a common denominator in mimesis: “In mimesis, tightly interfolded like cotyledons, slumber the two aspects of art: semblance and play”. Their historical significance becomes evident in the ‘Auseinandersetzung’ of first and second technology. In this demarcation the conceptual frame of mimesis is negotiated. This negotiation, or more literally “mutual deposing,” is comparable to an act of translation that makes different languages recognisable as “fragments of a greater language”, as Benjamin puts it in “The Task of the Translator”. What is at stake here is the question, in what circumstances first technology is naturalised, that is to say, turned into second nature.”

This is very to the point, I think. And Elo concludes a little later….“If we study Benjamin’s media aesthetics in the light of his early philosophy of language, visual literacy and its further training and practicing turn out to be intimately related to the dialectics of nature and technology as well as to the historical transformations of language. It thus seems highly relevant to consider technical transformations of media, such as the digitalisation of photography, in terms of translation and “mutual deposing” of nature and technology.”

The goal of critical judgement is then to resist the reductive terms often used, terms that are from a language of instrumental reason, and which are already well co-opted by a system bent on disfiguring the psyche, in order to blind people to the history of world suffering and conflict which are hidden in plain sight by all artworks regardless of the medium. Hence the tacit encouragement to not look too hard. At anything.

Speak Your Mind