Mathew Simmonds

“Everything in this world reeks of crime:

the newspaper, the wall, the countenance of man.”

Charles Baudelaire

“Theories that level suffering by proposing that all subjectivity is born from subjection

and exclusion, however, cover over the suffering specific to oppression. In so doing, they risk complicity with values and institutions that abject those othered to fortify the privilege of the beneficiaries of oppressive values.”

Kelly Oliver

“If the print revolution heralded the beginning of the end for our memory retrieval capabilities, then the post digital world is arguably deteriorating our abilities to a state of amnesia.”

Fiona Shipwright

It would be hard to imagine Hollywood becoming more jingoistic than it is today. What is interesting, I think, is that for the fifteen years I worked in film and TV, as both feature writer and staff writer, I only met one person who had served in the military. ONE. One out of the thousand or more people I dealt with for over a decade. He was a Vietnam vet who had become a writer. A very interesting guy from the backwoods of Appalachia, he claimed not to have ever brushed his teeth until boot camp. He wrote virulently anti-military drama. But that was it. One writer. And yet, today, if one goes to network or cable scripted drama you will find an almost constant reference to the U.S. military and to the heroism of soldiers. And oddly, and perhaps its an anomaly, but there seems to a huge reliance on widowed wives of U.S. soldiers. It is a plot device in, literally, dozens of shows just this season. All from writers and producers who themselves have never served in the military. Curious.

Now, I have been bombarded of late with opinion from a variety of sources and people in the U.S. on the topic of Syria. Again, I am not sure why exactly this week, but happenstance perhaps. And what is shocking is that these are people, for the most part, who would self identify as liberal, and yet the information they have is wildly reactionary and Russophobic and almost nakedly and obviously connected to the U.S. state department. At least to the Democratic Party, and probably to both, and to the C.I.A. as well. Things like Pulse, which seems to have connections to the Carnegie Endowment for Peace (boy is that a state dept title if I ever heard one) and publishes writers such as Charles Davis and Idrees Ahmad. This is the newest incarnation of the cruise missile left. Except it’s not even nominally leftist. In fact Pulse published a piece by someone named Lelia al Shami. This piece advocates for the support of the moderate armed Syrian resistance (of whom scant evidence seems to exist) and the downfall of the evil {sic} Assad. But see, I find that anytime Assad is being castigated in print, it comes with a guaranteed anti Russian addendum. And a de-facto tacit (albeit hand wringing) support for the U.S. As Samir Amin once put it, a few years back, ‘it’s always a question how these groups get their guns’. Indeed. Why has ISIS not attacked Israel, asks William Blum. Yeah, how about that. The thing is, the left today is increasingly a branded hipster left. This is media manipulation, image management, not politics.

Nicolai Crestianinov

I wanted to write about space in narrative, in light of this growing jingoism. I say that because there is a both simple and a complex pair of connections to the ways people *view* the world and then make it into a story. In a sense, space in writing is closely aligned with what is usually called ‘poetics’. But its far more complex than that (what is popularly known as that), obviously, and it is also something that I think defies any sort of systematic attempt at definitions, really. One of the distinct qualities I experience watching popular entertainment, meaning mostly Hollywood film and TV, is a sense of suffocation, or strangulation in the story and in the characters. One feels only in that mimetic sympathetic way a kind of constriction in the chest. In one way this is about changes in the idea of what character is meant to be doing, of what it ‘is’, exactly. And this is connected to the resurgent fascism that washes over Western societies today. And all of this is linked to the way amnesia, forgetting, loss of memory, seems to inhabit living space, and how stories are told. A space inhabited by amnesia is one that registers a certain blankness. I use the word *inhabit* metaphorically, but there is something that feels quite literal about it, too. Fiona Shipwright has a cool short essay over at Uncube about the importance of architecture to memory. And she suggests that the way most people use the internet, accessing vast stores of information, is the equivalent of non-place. And stories today seem to increasingly take place in non-spaces. Slightly different sorts of non-spaces, but related. A number of writers have taken up this idea of society losing a sense of collective memory. Jerome McGann writes about the loss of reading and the implications for convenient forgetting. The digital age privileges this ‘super present’, and it is attached to the solicitations of an age of marketing. One aspect of the erosion of community is the attendant erosion of memory as art of solidarity. But there is another aspect to rising amnesia and that has to do with the way stories are used. And maybe ‘used’ is the wrong word, although I think maybe it’s not exactly incorrect either. This is also a part of the general loss or reduction of experience. I read somewhere on social media the other week someone saying how the government was always pushing ‘crappy modern art’. I don’t even recall the context and it might well have been true in a sense, but that kind of remark is one I hear constantly; and it is usually expressed in a tone of hostility. And it is often the left as much as the right. In fact more because the right wing today, the new fascists, openly hate culture of any kind. But I think the causes of this hostility, across the political spectrum, has to do with a sense of not wanting to ‘waste’ the effort or time in engaging with difficult cultural matters. It is also just defensive.

Matthew Brandt, photography.

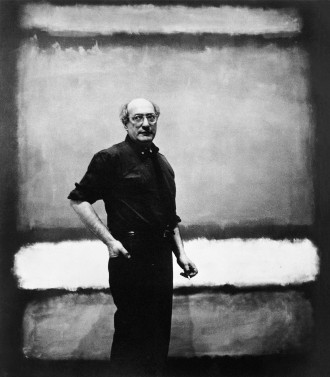

It reflects a sense, in the U.S. anyway, of that long standing fear of being taken for a mark. It is easier to ridicule a Tony Smith, or a Mark Rothko than it is to really explore why they might be important. One cannot explain in three sentences why Rothko matters. Americans in general are terrified of being ridiculed. The age of snark and sarcasm, but also of shaming and ridicule. In literature there is a certain built in tolerance for hipster prose, the kind that writes about how pointless it is to be writing. But returning to Hollywood for a moment in this, the new jingoism takes place against highly unreal landscapes, but not just unreal, for they are unreal is a particularly disturbing way. Everything coming out of Hollywood, or nearly everything, is borderline camp. Shows such as Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. are steeped in irony and are, essentially, ironic cartoons with live action. The appreciation of this stuff is predicated almost exactly upon Sontag’s old definitions of camp.

The issue though is ‘character’ now, in mass entertainment, and it is something very different than what Tolstoy thought it was. There is a set system of behaviors and actions, and reactions, that are like paint by number templates. And nobody is very forgiving. If there is one single thing absent in TV and film today it is forgiveness. And if it does occur, it’s really not occurring. I watched one show recently in which a character made a long speech that ended with his saying ‘I forgive you’, and at that moment the audience realized the person he was speaking to was in a sound proof room and couldn’t hear him. This is the best metaphor for contemporary narrative I can think of.

Malerie Marder, photography.

So if an entire society is actively ‘forgetting’, all the time, then the need for story is diminished. Or it has at the least changed dramatically. For stories now, in popular culture, are always stories the audience already knows. One might suggest the same was true of Greek tragedy, but there the knowness, as it were, was a part of a complex architecture of memory, of collective history. Here a narrow class of wealthy white writers and directors and producers are manufacturing a constant hyper repetition of the known, but of the amnesiac known. The audience knows this story of not knowing being told by non characters situated in a non-place.

So pervasive is this kind of product that the introduction of real characters in contexts of real history, appear intimidating and needlessly difficult. And this has given rise to a certain kind of conformist surrealism (David Lynch is the perfect example of this, but in its way American Beauty was another, or Fight Club). The manufacturing of the ‘weird affect’ is really a way to interrupt the actual uncanny, and to short circuit the deeper layers of collective memory. And on a psychoanalytic level this collective is mediated by individual histories of a sort today that suffer their own disfigurement. The shell of a person, which Joyce McDougall has written of so extensively. It should be said that the Palahniuk novel Fight Club is quite a bit of another ‘thing’ altogether than the film.

“Subjectivity is constituted through response, responsiveness, or response-ability and not the other way around. We do not

respond because we are subjects; rather,it is responsiveness and relationality that make subjectivity and psychic life possible.”

Kelly Oliver

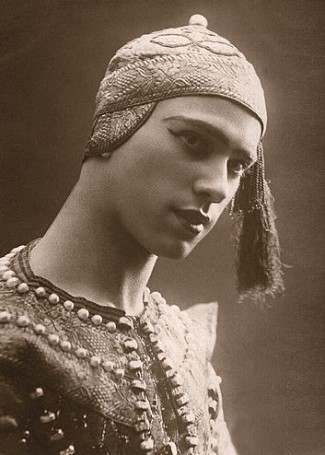

Vaslav Nijinsky, 1916. Eugene Druet, photography.

Kelly Oliver has written some quite cogent studies of how subjugation works on individuals and affects their development. I think finally she is wrong in some of her conclusions, but I also think she makes important observations about class and the long shadow of social hierarchical deprivations on both individual and community. And what she says of responsivness is very interesting in terms of writing. I used to say to students that character comes out of dialogue, not the other way round. It is the very same idea — people are not pre-formed and complete, but rather fluid, incomplete, and instinctive. The character, the subject, is always in the process of reacting, and this is also, I suspect, how languages develop. This is one of those questions with cave art raised by Leroi Gourhan. And more, with how memory is linked to knowledge in ways that it is not linked to digital information.

“The training of the body is based on behavioral patterns

learned from participating in the social life of a group. In some cases the training is

conscious and delibarate but in many cases the training of the human body takes place

within the context of the ordinary daily-life. Moreover, the gesture is not simply the

skilled movement of the body but also the knowledge that guides the skillful sequence of

actions. Leroi-Gourhan stressed the social nature of memory in human societies.

Memory is not the property of the individual but rather of the collective members of

society. Thus, to say that gesture is concrete and individual presents only one side of the

coin. While this is true, it is equally true that gesture is necessarily collective and abstract

in the sense that gesture involves not only the movement of the body but also the

knowledge that structures this movement.”

Michael Chazen

‘Leori Gourhan among the Cyborgs’

Gourhan also pointed out that today, under late Capitalism, people have stopped participating in the creation of aesthetics. They consume them, and perhaps in some second order or register they repurpose them, but mostly they passively consume them. This is an area Bernard Stiegler touches on when he suggests that politics is aesthetics, today. By which he means that if taking ‘aesthetics’ is the widest possible definition, and including taste and perception and feelings — that aesthetics is then social because we are living together and speak to each other and share opinions and judgements and experiences. And that’s right, but it’s also increasingly not right. What mass culture is doing (per Stiegler) is *syncronizing* aesthetic experience, and the most profound technical apparatus employed is TV. And even way back thirty years or so ago, Jerry Mander was saying the same thing in his book Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television

Daniel Ross, in an article on Stiegler writes:

“This is not only a matter of cinema and television. Industrialisation itself, the rise of industrial production, depended on nothing other, largely, than the grammatisation of human gesture and its inscription in the programs of industrial machines. What previously was a matter of the techniques with which the hand worked with tools, transmitted generationally, became the domain of machines whose techniques it was no longer necessary for workers to know or understand. We can speak of a process of the retreat of the hand, analogous to the retreat of the foot in the hand which characterised the prehistoric process of the conquest of the upright stance. This retreat of the hand is a grammatisation of gesture amounting to the destruction of skill, that is, of forms of knowledge of how to do and make, and it is what Simondon referred to as the proletarianisation of production (the key point here is that Simondon re-writes Marx to make clear that proletarianisation is less the creation of a new class than it is a process of the destruction of knowledge, affecting everybody).”

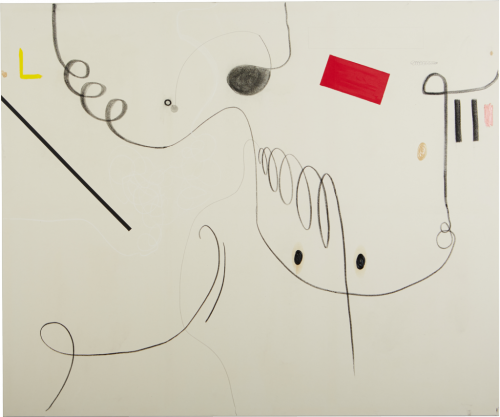

Christian Rosa

So, here is a subject who is situating him or herself in relation to the social hierarchy and others in it, as well as suffering an increasing kind of deprivation born of losing the knowledge, the direct and physical intelligence of gesture, and memory. And both are partly collective. That quality of that used to be called shell shocked (after WW1) and is now called PTSD or some variant, is not always the shutting down of receptivity, but can be, and probably often is, the shock of having no gestural memory or skill. I see this, say, in airports as one watches the crowds passing. There is a generation of graceless youth. Some are remarkable athletically, but lacking in this gestural poetics. Watch film, the little there is (actually almost none), of Nijinsky. Perhaps this is not true but I cannot imagine a body or dancer of that sort being found today. But that’s a complex question, really. Nijinsky’s physical genius was inseparable from his psychic fragility, and his facial expressions which evoked a profound emotional openness. And maybe that was his erotic pull as well. The intelligence of gesture, skilled movement and the memory of something collective, not individual, in the body.

Dots and rhythmic line patterns were evident during the Paleolithic. There is evidence of the representation of figures from thirty thousand years ago. Twenty thousand years ago there were groups of figures and many stylized representations. Five thousand years after that, roughly fifteen thousand years ago, the sophistication in drawing was dramatic. By the time of the Altimira cave paintings, maybe ten thousand years ago, there were both stylized representations and a return to ‘realistic’ drawings of animals. There is really not much known, finally, about who made these drawings and paintings, but it is clear I think that language was born out of this interplay between graphism and drawing, that those rhythmic clusters, patterns, were becoming a kind of pre-alphabet. Gesture, a skilled hand at work. And it must have been recognizable to those in these early communities, that certain patterns meant certain things. Memory played a crucial if not essential role in the life of those people in the Paleolithic. Abstraction, as Gourhan says, led to both written communication, language, and branched off into a return to realism. The point here is that abstraction was always, for early man, a kind of ritual language. The memory of the individual was caught up with symbols and even with decoration (what today might be called decoration). The body is activated by recognition of pattern, the memory is activated, and one feels something personal in the collective. Today, I think perhaps it is the opposite. Mass culture like TV out of Hollywood, posits a collective that makes judgments based on what isn’t felt. The individual feels only a rote identification with the collective. The collective is not personal. It is that to which one subscribes, like buying a political abonnement. This dynamic, this is the sense of entitlement the bourgeoisie clings to — the purchase of the right to exist.

Mathew Simmonds

The mimetic feeling that is inextricably linked up with memory and collective history is largely absent. In its place is the certificate or commercial document that grants one permission. The contemporary Westerner is very caught up with permission. And this is partly the result of how Capitalism has trained the populace. For without active memory skills the subject is predicated on various immaterial (even implied) transactions of allowance. Permission to buy this house, to ride this bus, to own this car. And the digital archive that is the internet occupies no physical space, it forms no space, not even an image, really. One does not remember the history out of which one comes, but rather accesses, if needed, the data that verifies this. Verification though is increasingly tenuous. But this is partly the loss of the past, altogether. The hyper present is a non place where one still needs documents. A passport to nowhere. A passport granted authority by a structure, a state, that also exists in non space. If you asked the average American where his or her country was, the answer would be some kind of map reference.

“The black man lacks the advantage of being able to

accomplish this descent into a real hell.”

Frantz Fanon

The colonial mind set of the West intersects with memory, and with the formation of the subject, or identity. The white person who asks ‘what can I do’ to a black man or woman is exercising a final form of privilege. The underclass today, black, Arab, and Latino, and in differing ways, too, transpeople and immigrants of all kinds, are denied their own voice. It amounts to the final White ownership of suffering. And voice is hugely important, here. For the alienated white westerner the expression of their own suffering, anxiety, fear, or sickness (PTSD, ADD, etc) is exactly that for which they feel they have purchased permission. Their voice, their language, and their non-space is what makes up the ‘hyper now’. The subject formation of those deemed outside is one in which they are not even allowed their own psychic lack. This is the impulse for erasure that dominates Western imperialist politics. Erase not just history, or rather, doing so makes those whose history is erased into phantoms. The muslim is invisible, except as a template for the White westerner. The black inner city youth is invisible, and when he or she has the temerity of ‘appearing’, it means the appropriate action is to disappear them. So two things seem to be going on today; the loss of history, of space, and of memory is accelerating, but at the same time the privileged white westerner is making *their* anxiety, fear, confusion, into a kind of club to beat down those without the abonnement. The last bastion of privilege for many is in their narcissistic angst. This is the model for countless Hollywood TV shows and feature films. Actors of color, or writers, are granted day passes if they conform to dimensionless cut outs. The black characters in today’s TV are largely there, if not always there, to make the viewer aware of their own whiteness. Or, of their existence, finally. I exist because none of you do.

Janina Green, photography.

This goes a long ways to explaining the quality of suffocation in narrative. For characters are not part of a landscape in which collective memory is be accessed, or in which the gesture and voice is that of the unpredictable. And here that sense of absent memory starts to literally erase the landscape. Shows like the recent Jessica Jones on Netflix (based on a Marvel comic) takes place in an empty and weirdly airless New York City. It is worth noting that the black character, the ‘unbreakable’ man, is one that I doubt any but a white writer would create. His grief is one dimensional (for a dead wife) and even the fact that his skin cannot be punctured or burned feels oddly like a colonial cliche trotted out in new attire. The show’s creator and head writer is Melissa Rosenberg, born in Marin County,and whose father is Jack Lee Rosenberg the psychiatrist. But I digress. The white lead protagonist is able to feel and get in touch with her emotions through her affair with the unbreakable black man. But really, this is a minor point because the real overriding quality of the show is that there are no characters. There is only this strange disconcerting melange of science fiction, fantasy, comic book and titillation. Even the logic of the super powers many of these characters possess is inconsistent. And perhaps this is so obvious in this particular show because of the use of voice-over narration. When Robert Mitchum narrates his fatalistic descent into eventual murder in Out of the Past, it is from the point of view of his own death, and it is about memory. How we remember and how we question our own memories and by extension our choices. In Jessica Jones the narrative voice over seems to come from no place. It is spoken from the sound stage. It is not a confession, even, but a sort of map to events. Except nothing is questioned. Not even having super powers.

“…the destruction of the past, or rather of the

social mechanisms that link one’s contemporary experience to that

of earlier generations, is one of the most characteristic and eerie phenomena of the late twentieth century. Most young men and women at

the century’s end grow up in a sort of permanent present lacking any

organic relation to the public past of the times they live in..”

Eric Hobsbawm

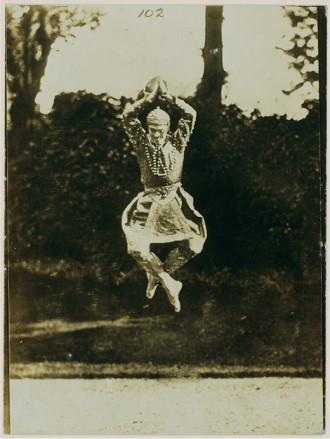

Nijinsky, 1910. Eugene Druet, photography.

“The house is not only, therefore, a building in which a group of

people live. It provides more than a shelter and spatial disposition of

activities, a material order constructed out of walls and boundaries.

Over and beyond this it is a medium of representation, and, as such,

can be read effectively as a mnemonic system. Many anthropologists

agree on this point. The house has been compared to a book in which

is inscribed a vision of the structure of society and the cosmos…”

Paul Connerton

Buildings are always linked to Nature, of course. To ideas of boundaries, enclosure, exposure, safety etc. All buildings. And I think that one of the missing elements in much film and TV today has to with how architecture is ignored. I wrote of Antonioni and Bertolucci and how their films so profoundly integrate architectural space into narrative. I cannot think of a contemporary film that does that.

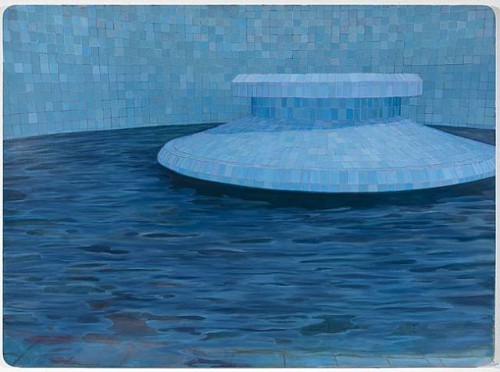

The invisible underclass today is inevitably going to recognize their own invisibility in the white world. Kelly Oliver discusses Lacan in this respect, somewhat incorrectly I think, but one part is very germane here. That essential lack, the split of inside and outside, which the subject then re-knits in various ways by manufacturing coherence in the outside world (at no small cost psychically) is for the abjected outsider a different sort of struggle. The mirror stage as a social reality (which Fanon articulated) means that for the outsider, the underclass child, the formation of the super ego is doubly toxic. For it always a white super ego. Authority is only white authority in white society. The colonial plantation owner is the modern patriarch. The figure of the sugar plantation owner on horseback, scanning the land he owns is an indelible image. For contemporary architecture always creates the open space as one under surveillance, not just from CCTV or other surveillance technology, but on a deeper level it is the place which is there to be viewed from a privileged vantage point. The open space offers itself to be surveyed, at leisure. Openness is entwined with leisure, with a respite from labor. It is a weird commingling of 19th century residual factory models for labor, and the rise in security spaces as forms of reassurance for the bourgeoisie. The public commons today, of course, don’t really exist. But in office complexes, the open atrium or outdoor square is to be viewed rather than inhabited. In a sense the privileged classes don’t ever inhabit commons areas anyway and those who resting on benches by the water fountain in the square are de-facto stigmatized as the laboring classes, as those who *need* breaks. Those who bring their own lunches. The idea of rest is one that is compromised today, anyway. Partly the legacy of a Puritan country, but also the sense that work is something highly mediated in terms of perception now. That all said, I think Oliver is right that oppression is a neglected aspect of subject formation because of the positing of a normative white male model for experience.

Daido Moriyama, photography. (From Farewell to Photography, 1972).

Lacan saw alienation being interrelated with our existence in a world alien to us. A world we did not make. Of course this is why memory is so important, on a collective level especially, for the tending of those psychic wounds of childhood alienation are meant to come from the common history of a people, a society, a culture. And it is here that I think a common error takes place in regards to art and culture. That hostility I spoke of above, to modern art, is really a hostility to abstraction at bottom. And yet arguably abstraction is the primal expression of human beings. Why are there unrealistic cave paintings at all? Why did man develop patterns and substitute these decorative patterns at a certain point for grammar. We speak the language of abstraction. That is poetry in a sense. So when I say narrative and space are related, what I mean is that the ‘voice’ of the writer, or character, is a voice of exploration. It is not the voice of the known. If it were it would be an Ikea catalogue. The hostility to abstraction is Puritan, firstly. It’s seen as too easy. Aw hell, I could that. Give me a can of paint and a roller. I can do a Rothko. Secondly, it is the hidden fears of mimesis, which is something I’m coming to see as far more prevalent that I thought. And this is, I suspect anyway, because of how destabilizing is any interruption of the hyper-now. One must remember, a remembering not archived digitally. And it is, as a side bar, interesting that the concept of *remembering* has taken on a kitsch marketed reality today. Memorial ceremonies, or all state mediated offical acts of memory are really, without exception, really acts of forgetting. The sentimentalized memory activity, or pseudo ritual is one I tend to associate with things like the funeral of Princess Di. And even when genuine commemorative gatherings take place, at a grass roots level, there is an insidious creeping kitsch quality that needs to be better guarded against I think.

Things like the politicans marching together in Paris after Charlie Hebdo is an act of occupying grief by the state. Yes it’s a photo op, but it is also a stealth act of psychic occupation. Grief is held hostage by war criminals, arms linked, making *serious face*.

Kasper Sonne

The political fables or propaganda of the West now resembles episodes of shows like Jessica Jones. For whatever reason this week I was thinking about Nijinsky. For what is often forgotten is that Nijinsky invented modern dance. The le dieu de la danse of the Ballet Russes, choreographed only four ballets. All short, and only one remains; the eleven minute Afternoon of a Faun. It is easy to forget how radical these works were in comparison to the Imperial Ballet or other Diaghilev ballets. They were not really ballet. They were to dance what Artaud was to theatre. And perhaps in another way what later Moriyama was to photography. The myth of Nijinsky was due partly to the tragedy of his madness, and part to the preternatural virtuosity of his dancing. In that sense Glenn Gould comes to mind, too, and Coltrane in that sense. Artists who projected a form of mystical insight because they had transcended notions of technical skill. In the case of Nijinsky, of course, there is like with Artaud, precious little left of their actual work. And perhaps that is partly the connection here to ideas of memory and digital age archiving. There is no archive, there is only the fragment, and the first hand reportage. And despite a surge of renewed interest in Nijinsky, the comprehension of him remains tentative. Paul Cox’s terrific film (The Diaries of Nijinsky) from 2001, with Derek Jacoby reading from the diaries, maybe captures better than anything the enigma of art and gesture and finally the cost to the vulnerable and fragile such as Nijinsky. I say that because one cannot contemplate Nijinsky without delving into the reality of absence, of what is missing, and of cultural memory. You cannot conjure Nijinsky without Russia, winter, and the looming Bolshevik Revolution, and WW1. Or of the Imperial Ballet and the teaching, of Balanchine and Pavlova, and Tamara Karsavina. Or Nureyev — and this is the central thing, here. Memory is not the Sherlock Holmes ‘memory palace’, nor is it hyper retention or memorization or super computers. The real space of memory is gestural, is shadowy, and changing, even. It is sensual, too. The collective, the communal and communistic, is always eroticized. It is Capitalism that strangles the sexual. Nijinsky was by all accounts quite well read, and even articulate when he chose to be, but he was socially maladaptive, and almost phobic about crowds and lack of space around him. He had tarter features, and that sense of outsider, of Pole and Tarter combined in him this odd ability (and need) to retreat into himself. He was not like most of those he went to school with. Today I am sure he would be medicated, diagnosed on a spectrum of something and forced to be happy.

Mark Rothko

Capitalism, the rabid late stage Capitalism of today, requires this steady diet of pseudo porn, titillation, because it must compensate, fill in the clear cut and denuded spaces of the mega-super-ego. White men in tailored suits, wearing Audemars Piguet Royal Oaks, and three thousand dollar bespoke shoes are never as sexy as the kitchen staff. Therefore the kitchen staff must be kicked to the curb. For no other reason than that. Because, as Richard Pryor said, somebody gotta pay.

Kelly Oliver, quoting Fanon again, and apropos of the unbreakable black man in Jessica Jones:

“The morality of colonialism reduces the colonized to their bodies, which become emblems for everything evil

within that morality.This identification of the colonized with their bodies,and more specifically within racist culture with their skin,leads Fanon to call the internalization of inferiority a process of epidermalization.The black man is reduced to nothing but his skin, black skin, which becomes the emblem for everything hateful in white racist society.”

Watching that series I kept feeling this quality of unease. There is no space for character, for not knowing, in the writing, for a place that would allow the actors to breath. My sense, when I have taught playwriting, is that most dialogue is improved if cut down by half. The actor, who is functioning out of memorization already, must be able to react not just to the other actor, but to the language. To speech, both his own and other actors. And to remember his remembering, for that is always a part of performance. Great actors really are mostly listening. When one listens, one forgets the body; and the forgotten body, the forgotten body that is your own, is a body that resembles the monk or shaman. Listening is very close to meditation in this respect — and directors like Peter Brook or Kantor understood this, and in film Ozu and Bresson, Pasolini and Straub. In Hollywood today, in prestige products like The Affair or The Leftovers, there is a sense of anxiety in the acting. The eyes betray the actor. For when there is no breath, no listening, there is only information. One could be reading that Ikea assembly instruction sheet. For the actor isn’t listening, and therefor is caught thinking about what he or she is doing. Which is mostly collecting a paycheck. That form of thinking is just neurotic — and this is important in terms of narrative I think. The loss of memory and space for memory mirrors the actual loss of organic space. In a landscape of security and surveillance the populace are acting out a bad movie, for it is a movie without a story. As actors in their own bad movie there is no expectation that anything is other than a prop. Everything is a set, is a false front, and there is no expectation for depth, or something *behind* the front.

No sentient human should be able to tolerate the naked lies of Empire, should not vomit in the face of the speeches of Nurland or Samantha Power, or Joe Biden or any of a dozen generals and admirals. For these are bits of political theatre in which everyone but the speaker is invisible. Americans in particular have no *image* in their head to attach to the word Syria or Libya or Honduras. And one aspect of this hatred for Muslims that is erupting is that none of these people that scream in rage about terrorists and headscarves can remember anything. They do not have a memory of their own society, they only have an artificially manufactured *now*, and at best a mis-assembled bunch of data retrieved off one screen or another.

Adriana Varejao

People are trained and hence normalize the absence of story. And if amnesia is normalized, as is the natural affect of absent narrative, then everything must be done faster and faster. It was Laplanche who, working off Freud, said that obsessional neurosis was an internalized sado-masochistic tension between the ego and the new more ruthless super-ego. The hatred of Muslims or Russians or black teenagers is all the same hatred; and it is obsessional. It is the new hyper accelerated obsessional dynamic and as Kelly Oliver observes, this is experienced by those who are targeted with this hatred as social trauma. The constant anticipated aggressions of the White privileged colonizer (essentially) is part of the anxiety experienced by all of the underclass today. There is only reflected back to the poor and outsider a set of ambivalent feelings. The crucial thing here is that white privilege, in an era of amnesia, is only supportable because the landscape of amnesia is one that reinforces one basic plot point — the civilizing mission of the colonizer. The rhetoric of the Imperialist is beating on that single theme, however it is dressed up for variety, and that is civilize the savage.

The popularity of privileged conditions, illnesses du jour, are expressions of being human, of proving existence in a sense. The savage cannot suffer sleep disorders or eating disorders or Aspergers or ADHD. For they cannot even be allowed that. This point is Olivers but also Spivak and Kristeva, too. And this is expressed another way, as well, and that is in the architecture of power. The events of memory, or military victory, are not built to remember but to forget. Rituals of memory are always about forgetting. Their role is, again, to grant permission to forget. And *entertainment*, in the form of Hollywood TV and film, is an industry of forgetting. Don’t remember, sleep. Responsibility is about yourself. This is the mantra of white privilege today. ‘Take care of yourself’. The institutionalization of self involvement. You OWN your condition. You bought the ticket. You’re a season ticket holder in fact. Recreation, tourism, both are part of the industry of memory loss. Nobody *vacations* (verb) in order to remember, to reflect, but rather to have fun and forget. The best party is the one that can’t be remembered. Hollywood comedies are turned out by the dozens now with this single theme. White men who can’t remember what assholes they were.

Nijinsky, “Afternoon of a Faun”, 1912.

Community structures, and this means, really, mostly, pre-modern societies, but to a degree it includes in some partial way post industrial unions and guilds, are linked to ‘learning’ a trade. Apprenticeship is handed down often. And in another sense it is part of community knowledge, historical skills, which carry rituals of inclusion. Today, work is abstracted — the actual toil is all too literal, but the experience of it is just another thing to forget. There are no peer bodies of shared knowledge. This was one of the observations Mike Davis and Leon Bing made about LA gang culture; that joining a gang meant inclusion and access to trade secrets, to a special knowledge. As Leon used to say, the Crips and Blood don’t have to hold recruitment drives. The life of the contemporary working class in the West, in the U.S. most acutely, is one of constant unrelenting coercion. And this is relevant for how and why culture and art is treated with such hostility. That crappy modern art. I so don’t care. Etc. Well, of course not. Because the necessary investment in reaching that threshold that is autonomous experience is one that is perceived as much too difficult. It is also time consuming. Art is time intensive. And there is no paycheck at the end of it.

It is, as I said at the top of this posting, impossible to imagine mass culture being any more reactionary and jingoistic than it is now. And so internalized are the these forms of substitute gratification and instant distraction, that the appreciation most people have for it is indeed highly mediated. Few people value mass culture, but they are granted permission to consume and *enjoy* it. Some of that enjoyment is to ridicule it, to some degree. And so internalized are the forms of ridicule that many are only barely aware that they ARE ridiculing it. One eventually comes to pass grades on the excellence of the ridicule before even the product. The culture industry is controlled by a relatively few relatively affluent white people. They create work that reflects their values. This kind of conditioning is now nearly total. And the idea of culture as an element of resistance barely registers and when it does, it is rejected. The conditions for discrimination in culture are blurred now, and as Jerome McGann says, the complex artworks of the past are now relics in the digital museum/archive, only to be examined as one might examine a early Etruscan stone carving. Dostoyevsky is no closer to the 21st century Westerner than are the cave paintings in Borneo.

The endless mini narratives of propaganda do far more than push the ideology of the Imperialist West, they also are at work sucking the air out of the environment, literally and metaphorically. And judging from the wholesale reactionary reading of Syria these past few months, the ability to read is lost with and to the same degree as memory.

“I do not like eating meat because I have seen lambs and pigs killed. I saw and felt their pain. They felt the approaching death. I could not bear it. I cried like a child. I ran up a hill and could not breathe. I felt that I was choking. I felt the death of the lamb.”

Vaslav Nijinsky

Diary

Thank you for the necessary ‘breathing’ space. Perhaps another and somewhat mundane example of amnesia and jingoism might be the current ‘full spectrum’ marketing assault of the ‘Star Wars’ shebang. Depressing to see such little resistance to such blatant militarism (is it me or do the actors look like blank-faced extras from a Nike ad?).

I would be interested to see where you would place David Mamet in the development of this militarism..and its accompanying amnesia…

@Bas:

Well, Mamet is a curious case in a sense. His early work was startling when it first came out. He worked with a theatre in chicago and those early plays still feel pretty good — sort of. But his basically reactionary quasi fascist sensibility was always there. And then he soon descended into self parody pretty quickly. But, even his worst film work….even the most recent, always has at least one scene or exchange, something, that jumps out at you. But I get the feeling he is a writer who has no idea what is good in what he does. And mostly his work is now rabidly pro Imperialist, pro Israel, and highly misogynistic. He had talent….whatever that is, but it was coupled to a deep lack of character.

Thank you- a curious journey, I suppose, from ‘Glengarry Glen Ross’ to ‘The Unit’ (and his outbursts at the time in ‘The Village Voice’). I wondered how much wider meaning- as regards ‘liberalism’ – could be read into this ‘transformation’