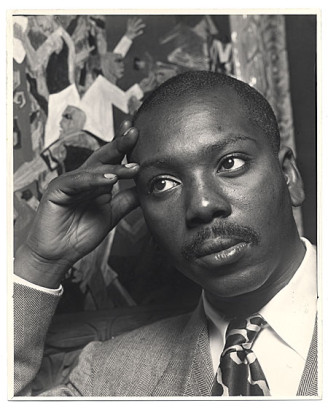

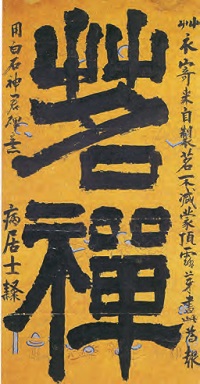

Chung Chang-Sup

“Art styles do not follow one another step-by-step or even as an ongoing argument. They disappear and reappear. They twist and turn. They rub up against other styles. They migrate and transmigrate. They pop up in very strange places. As in parapsychology, causality is replaced by synchronicity.”

John Perrault

“In Gutai art the human spirit and the material reach out their hands to each other, even though they are otherwise opposed to each other. The material is not absorbed by the spirit. The spirit does not force the material into submission.”

Gutai Manifesto (1956)

“In everything, it takes great effort to think up something new. And even if something is good it takes time for people to appreciate it. So if you are not strong enough, when you think up something new and important and nobody praises it, You may give it up. And instead you will start thinking up things that are not so new, but that please everybody.”

Shimamoto Shozo

Gutai Group, from conversation with group of children, 1956.

“Our ordinary language has no means for describing a particular shade of color. Thus it is incapable of producing a picture of this color.{ } Imagine someone pointing to a place in the iris of a Rembrandt eye and saying, ‘The walls of my room should be painted this color.”

Ludwig Wittgenstein

Dansaekhwa is the loosely defined movement of artists in Korea that rose in reaction to the social trauma of the early 50s. This was a both reaction to colonial wounds, and a borrowing of the disruptive vocabulary of Abstract Expressionism and to a degree, a bit later, from minimalism. Dansaekhwa is the major Asian painting movement of the second half of the 20th century, along with Gutai in Japan. Now, over at Frieze (in the persons of Sam Bardaouil and Till Fellrath, who exhibit this slightly creepy phenomenon of appearing literally everywhere the topic of Korean monochrome art is introduced in the West. The cottage industry vibe is distressing and unmistakable), there is an introduction of sorts to Dansaekhwa, but one that falls into the tiresome and profoundly simplistic narrative of CIA manipulation of Abstract Expressionism. So for the thousandth time, just on this blog, the impact of CIA propaganda on the almost entirely Marxist group of painters, a good many who were Jewish as well, or immigrant, was minimal. And the social realism of the Soviet painters by the 50s was just appallingly bad, so it’s not as if much propaganda were actually needed. The Ab Ex painters should be regarded as radical voices that influenced painting globally, really. And the promoting of abstraction from NY was more to make New York the new New York, after it was the new Paris…and to keep it that way. It was PR intended as much for Paris or Berlin and London as it was for the rest of the planet. The fact that several key collectors (and indeed probably some with CIA ties) bought and promoted the New York School, ends up having little to do with the work itself. Same with Dansaekhwa, which was caught in the West’s imperialist foreign policy, culturally as well as politically. The Korean War began in 1950, and that first central generation of Dansaekhwa, was born between the late 1920s and the end of the 1930s. Several were of the next generation (prominently Lee Dong-Youb). The Korean artists remain relatively unfamiliar although the Venice Biennale this year has certainly gone a long way to promoting the central painters. But the first salvo might be seen to have been the 2000 Gwangju Biennale curated by Yoon Jin-sup, who organized the special exhibition, “The Facets of Korean and Japanese Contemporary Art,” (sic). So, how does one evaluate this work in light of the sudden pimping of the Western arts establishment?

John Cage

The answer is complex, but the best of the Korean artists under discussion are very convincing, and two, at least, feel particularly strong (Yun Hyong-keun and Chung Chang-Sup, both of whom are among the oldest of this group. The latter died in 2011, the former in 2007.). The fact that these two painters might well not be seen as part of Dansaekhwa even, is a telling point. Painters like Lee Ufan — the most recognizable name internationally today (I’d argue, anyway) is also, maybe, the most facile and easily approached. Though I mostly think he’s still very good (and associated with the Mono-ha group at one point). But all this points up the commercial industry that has grown up around painting today. Like the New York School, the first generation of Korean modernists were reacting to the acute turmoil in Korea following the end of Japanese occupation, and the partitioning of their country. That first generation rose to some prominence against the backdrop of the military governments of the 60s and 70s (South Korea sent troops to fight alongside the US forces in Vietnam from 1964 to 1973). That generation of South Korean abstract painters were highly criticized for rejecting figurative art (and classical calligraphy based work). A sense one gets from much of this work is that of retreat from commercially related imagery and Western corrupted commodity forms. The work is very quiet, if not silent, in the way Marco Tirelli is silent. Or, perhaps, the way monasteries are quiet.

Joan Kee has written a good deal on Korean art. But much of it is like this…

“Transposed onto the experiences of showing and viewing art, Lee’s emphasis on the encounter demanded a reallocation of agency between the artist and the viewer. In lieu of a schematic whereby the artwork passively transmits the artist’s intention to

the equally passive viewer, the artwork is activated only upon the viewer’s sustained engagement with the terms of its material and physical presence. If this proposed replacement seemed harsher than what Lee had in mind

when he wrote about wanting to show the world as it is, it was because Lee’s artistic practice was fundamentally vested in replacing particular systems of power. Lee’s practice actively searched for an alternative to authoritarian worldviews.”

This is really sort of the jargon of post grad art writers. *Agency* being a particularly popular word just now. But that paragraph (and there are many like it) pretty much means nothing. Now blame some of this on Lee Ufan, who as I said, feels a bit too much like a self promotor, but then self promotion has been a flaw of many great artists. But the point here is that Korean monochrome painters were reacting to oppressive conditions, a corrupt military government aligned with the U.S. Those first generation painters were instinctively responding to the material conditions of life and they did so in highly complex, impossibly complex ways, but certainly by, all of them, resorting to the traditional materials of Korean crafts, the papers and hemp, and by allowing the somber colors of the landscape and fields to inhabit their work almost to the exclusion of any others (with a few notable exceptions). The viewer always, in all artworks, engages from a position of mimetic reading that is shaped by their own history, and that is in highly reduced form, what art does. Whenever artists or critics talk about what they, the artists, are trying to do, it is a red flag. Same with critics or copy writers for galleries suggesting the artist is *exploring* gender or identity…..oh holy fuck, I mean what art ISN’T interested in identity? This is the Cindy Sherman virus of contemporary artspeak. And it is the fall out from the worst of conceptual art. Great writers and critics from John Ruskin to Leo Steinberg and Robert Hughes and even Rosenberg and Greenberg, or certainly John Berger and Hal Foster, never engage in this, and their clear opinions are such a relief in this day. From there of course one inches further into philosophy (er…theory) with countless others, Adorno, Lyotard, Benjamin et al.

Yun Hyong-keun

Something has quite possibly been lost in the work of younger artists that followed that first generation from Korea. Minjung Art (People’s Art), a movement that is either seen as following Dansaekhwa, or preceding it in some way were polemical and critical of the Dansaekhwa abstracts. But this repeats a lot of left criticism, apparently not just in the West, for work without clear moral and political message. That first generation of Dansaekhwa was itself a kind of protest work. The Gutai group in Japan, founded in 1954, followed a similar aesthetic trajectory. Theirs was a protest against conformity and obedience in post war Japanese society, and one of growing materialism. But again, if one googles Dansaekhwa or Gutai, and you go to Wikipedia, the same narrative (western) is imposed on the movement. Western critics suggesting the Gutai artists were seeking democracy and freedom. There is nothing in the Gutai manifesto to suggest this, not in relation to the U.S. anyway, but it’s now clearly a convenient narrative. Even in this kitsch narrative there resides obvious contradiction. The artistic climate of 1950s Japan was one in which the official work exported to Western markets was social realism. Gutai rejected this for the ability to find alternatives, most of which (but not all) were in abstraction, as well as theatre, and the precursor to *happenings* (in fact the ‘happenings’ of Kaprow and others were just following the model of Gutai). Again, Ben Davis in his critique of the recent Guggenheim show of Gutai work, has an aside about CIA uses of Ab Ex yada yada yada, linked to The Independent…not the most reliable source of information (and just lazy journalism). This is the left indulging the same debunked myths of the past as the right does when it trots out the de-bunked myths of NATO and Clinton and the Balkans. Such sloppy criticism is now becoming a staple of erstewhile leftist aesthetics

Gutai ran its course, certainly, and that much Davis is correct about. But much of the work that came out of its early years remains of lasting value, and it was certainly always (until perhaps the Osaka Expo of 1970) anti-U.S. and critical of the growing domination of society by mass culture. Both Gutai and Korean abstraction, after the war, were influenced by Abstract Expressionism. The key is how one sees that influence. If one subscribes to the kitsch CIA story, then such work was searching for commercial western markets. If not, then this work was anti conformist, humanist, and spiritual. It’s not that the CIA didn’t have cultural propaganda programs, or target the New York School, it was that it had minimal (zero) affect and influence on the artists themselves nor the artworks.

Chung Chang-Sup

One thing is clear, in both cases, they, Gutai and Dansaekhwa, were reacting to autocratic and militarist governments. And both those government had ties with the predatory and Imperialist United States.

“This leads to some curious results. If you take poetry out of Schoenberg and Webern you get Milton Babbitt.”

John Perrault

And Perrault is right, in that comment. And this is the thing with both Gutai and Korean monochrome, or Dansaekhwa, beneath the resistance was a good deal of poetry. And its useful to remember, that ideas of conformity have a different color and flavor in Japan and Korea, historically, than in the West. A Mishima could only have been produced by Japanese culture at that specific moment. So, too, Gutai and Dansaekhwa.

From Perrault’s essay on Gutai:

“What was Gutai’s secret? The art was sensational. And they had their own magazine to promote the cause. Jackson Pollock himself had two issues of the Gutai magazine in his library when he died. Gutai — for better or worse – reached out and formed alliances with two other artist groups on the so-called periphery — Zero in Dusseldorf and Nul in Amsterdam. There were also connections made with Allan Kaprow, John Cage, Fluxus, and Experiments in Art and Technology. Like Futurism, de Stijl, Constructivism, Dada, and Surrealism, Gutai had an international outreach.”

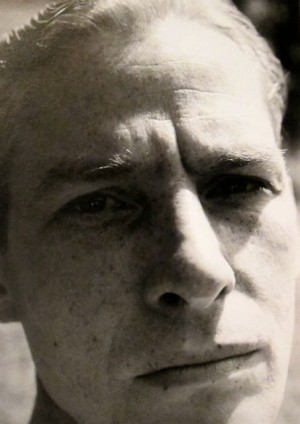

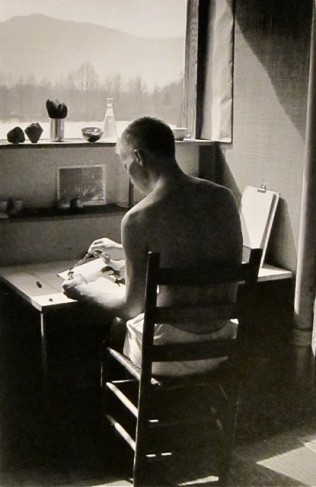

Kenneth Noland, at Black Mountain College.

The Gutai Group did much educational work with children. They took children’s artworks very seriously, especially Atsuko Tanaka, who lectured children’s groups regularly. Now, I feel as if there are lessons in all this for pedagogy. When I was looking around for criticism of Korean abstraction, or Japanese modernism, I ran across the Perrault essay. And Perrault is a guy who I had sort of forgotten, sadly. But he was always an astute critic, going back to his early work with the Village Voice in the mid sixties, onto his Art News reviews. One of the first openly queer art critics, he was a radical voice throughout his life. I did not know he died, suddenly, just a few months ago. Such voices are missed more than ever now, I think. And while Perrault was not officially a leftist, his sensibility was always radical and outsider. And when I think of pedagogy, I think of that sort of literate but anarchic radical voice. The voice of queer radicals that I somehow feel is missed in a sense, today, for the forces of assimilation and integration are huge, at least as the affluent gay white male orchestrates the narrative. Or rather, I miss those voices in the arts. Remember that the term ‘gay liberation’ had its origins in the sixties, as a co-responder as it were, to collective oppression; it was aligned with Marxism and women’s liberation, black radicals and sixties anti war movements. It was an oppositional voice to earlier gay rights movements (Homophile) who suggested social integration was the goal, a social acceptance for homosexuals. But the gay liberation movement — and the short lived magazine Rat — were revolutionary, really. They demanded social change, not adjustment by queers. Carl Wittman (quoted by George Haggerty) says “chick equals nigger equals queer”. I am digressing wildly here, but it is important to remember that these forces of adjustment, the limited hang out approach to containing real social revolution, has been at work with both feminism and gay rights.

And it has certainly across the board served to help suffocate aesthetic radicalism, by firstly just diminishing the idea of artistic importance. Two posts back I wanted to touch on Black Mountain College during the 50s (and late 40s). For out of these groups, whether institutional (sort of) in Black Mountain, or like Gutai, or Nul, or Fluxus, or earlier Dada …the goal was not career advancement. When I read the shit turned out by pretend leftists like Salvage, I feel an enormous sadness. For the sensibility is not radical, it is provincial and commercial and narcissistic. It is the smug voice of comfort. My personal sense is of a rising tide of *rationality*, of covering your back, not taking too many chances, and hedging one’s bets. And this is the result of a society of intensified fear and paranoia. The culture of risk management, as Randy Martin put it.

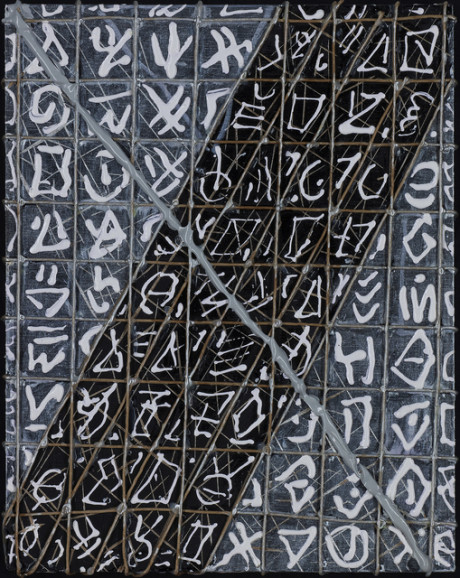

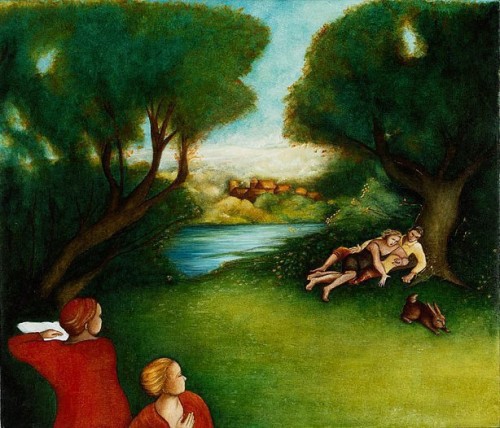

Shuji Mukai

Theodore Dreier and John Andrew Rice founded Black Mountain College in 1933. They, and others from Rollins College in Flordia, came together to create an interdisciplinary and experimental arts college set in the Blue Ridge mountains of North Carolina. By the 1940s the faculty included Josef and Anni Albers, Jacob Lawrence, Elaine and Willem de Kooning, John Cage, Alfred Kazin, Merce Cunningham, Charles Olson, and Paul Goodman. By the end of the forties, Robert Motherwell, Albert Einstein and William Carlos Williams had joined, as well as Buckminster Fuller and John Mason. The college went through a transition at the end of forty nine, but Olson returned in 1951 and along with Robert Creeley, created the Black Mountain Review.

Jacob Lawrence

“Was That A Real Poem

Or Did You Just Make

It Up Yourself?”

Robert Creeley

Willem DeKooning. Photo by Hazel Larson Archer.

John Andrew Rice.

Rice believed that students must find common ways of doing things. Manual labor was a part of the curriculum at Black Mountain. If today, one can almost immediately hear the snickers and jokes that would follow the introduction of that idea, it is because students have so completely abandoned any thought of institutional learning that does not further career, and involve testing. Morton Feldman wrote of Black Mountain: “…for one brief moment—maybe, say, six weeks—nobody understood art. That’s why it all happened. Because for a short while, these people were left alone.” And Joseph Bathanti noted: “In the summer of 1944 — 10 years before Brown v. Board of Education — Alma Stone, a 23-year-old African-American musician from Savannah with degrees from Spelman College and Atlanta University, lived on the Lake Eden campus while attending Black Mountain College for its 11-week summer session. Her visit occurred 12 years before Autherine Lucy, another African-American woman, matriculated in 1956 at the University of Alabama for a mere three days. (She was expelled “to ensure her personal safety.”) Although Lucy is generally credited as being the first African-American student to attend an all-white college in the Jim Crow South, it is arguably Stone who initially cracked that unassailable barrier — in North Carolina at Black Mountain College.” And there is a connection, too, obviously, to the Bauhaus. Not just with Albers and Gropius, but also the decidedly anti-fascist sensibility, which drew a number of Jewish thinkers and artists who had fled National Socialism.

Anni Albers. Photo by Hazel Larson Archer.

The evolution, though, led finally through the complex figure of Charles Olson. Now I consider Olson a hugely significant critic if only for his study of Melville, but all his writing had weight. But he was also authoritarian in a way Albers and the others were not, a decade earlier. And perhaps the shift from visual arts to literary arts narrowed the focus in a way. The ecstatic went out of BMC under Olson. The poets that came out of Black Mountain, under Olson’s directorship were certainly not trivial in any sense. But still, the Dionysian energy of that first half of the forties was likely never equaled. But the real point here is that it is difficult to imagine a similar experiment in pedagogy today. And I suspect there are quite a few reasons for that, but one of them has to do students as much as teachers.

I had a conversation recently about theatre with a friend …someone I’ve know for a long while in fact. And his frustration was less with the middle mind institutional apparatus for theatre than with finding students. His feeling was students *wanted* career direction and a chance to teach at some backwater school, churning out MFA writers who in turn would go teach at another even more back water school. There is no end to the banality of the culture at large today.

But also, I think it likely that the influence of Merce Cunningham was vital at Black Mountain. If you want to create an anti institution of arts education, make sure you have a few dancers around.

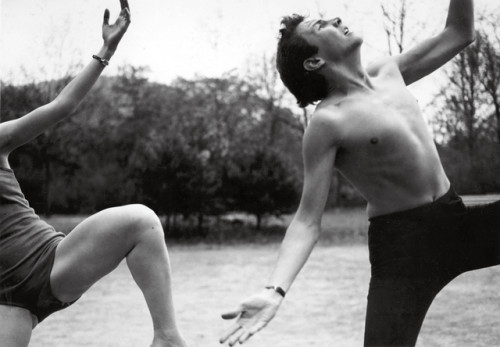

‘Elizabeth Schmitt Jennerjahn & Robert Rauschenberg’. Photo by Hazel Larson Archer.

There is an interesting short article on the Gropius/Breuer original architectural design for Black Mountain College, at the Journal of Art History.

“In October 1937, the Raleigh News and Observer published a two-page spread titled “‘You are the Curriculum You Make’, Unusual College Head Tells Unusual Student Body: Born of Academic Rebellion, Black Mountain College thrives under direction of man who prefers title of Rector to that of President.” The article exposes the controversial circumstances that led to Rice’s removal from Rollins College and then describes the “unusual” nature of Black Mountain College and its curriculum. The article also mentions Rice’s indebtedness to Walter Gropius’ German Bauhaus and the refugee Bauhaus masters, Josef and Anni Albers and Xanti Schwinsky. Ultimately, the unconventional origins of Black Mountain College as an experimental community, coupled with the number of Jews and German refugees affiliated with its Faculty, raised public suspicions of the College as a threatening local, “hotbed of radicalism”.

Jasper Johns

That slightly communist sounding label *Rector*…as funny as this is, in a way, it is also evidence of how little certain things have changed. The xenophobic bigoted paranoia of the U.S., and the Puritan backdrop that is always there. It never goes away.

The entire article is here http://journal.utarts.com/articles.php?id=15&type=paper

Needless to say, the Gropius and Breuer plan was too ambitious, and never built. But looking at it now, it’s a rather impressive vision for a direction that communal education could have followed, had funding, of course, been there. But the reality was the school built a single structure, essentially, designed (nominally) by Lawrence Kocher and constructed with student labor. May Sarton visted a friend there during the early forties and said that one of the qualities she found so remarkable in the school was that the building process, in which everyone took part, enabled a sense of everyone having daily imperfections to correct, a material problem solving, even if only rudimentary.

“There is continual dissatisfaction

and improvement and clearing of fundamental issues going on.”

May Sarton

Letter to Rosalind Greene, 1940.

There are a number of books out on the history of BMC, but the best is a collection of very informal recollections by former students and some fragments of interviews with faculty edited by Melvin Lane. What is so striking is that the without any oversight the college was allowed to do what it pleased. A student who came from working for a few years as a railroad brakeman, and with an aspiration to be a pianist, wrote amusingly of his own failures. But he remembered that he helped the famous harpsichordist Yella Pessl assemble her harpsichord, and this provided him with a special insight into art and artists. That was the level of learning, it was never goal oriented, per se. Later that student recalled that he had learned little in the way of skill, but had learned values, especially of respect and perfection of one’s creative vision.

Rodney McMillian

Albers almost exclusively taught drawing, with charcoal, and emerges in these memoirs as a serious intellect, and a man of extraordinary discipline and kindness. An almost surreal combination of qualities. The working class sensibility was set by Dreier, but it ran through all of the school’s faculty, and even in the most patrician teachers, like Albers and Olson. The faculty worked for almost no salary, and cooking was mostly communal and much of the food was grown on site. The recollections all bring to mind an erotically charged summer camp, with very smart people, with arguments about Bartok and Bach, about Franz Neumann and Marx, about French classical painting and Durer. But again, no major donor, no President, no board of directors, no trustees, not much salary really, and essentially no oversight. Such projects are not meant to really last. It may have been Olson’s mistake to return in fifty one and rekindle the idea but with a focus on literature. It was not unsuccessful, but it was not somehow as revolutionary.

The germane point of Black Mountain College, at least through 1949, was in the creation of social values and relationships. Not in art. Except that, finally, perhaps that is a good part of what art does. The epiphanic aspect of artworks, the awakening, the process of revelation is always bound up with social relations, and with memory. I find a lot of writing today, theory, about *forgetting*. But I think its less that (people do that too, meaning forget more) and more how people remember, the particular way individuals and society remember. The flawed and damaged process of remembering.

“I believe, for understanding the type of forgetting which is characteristic

of modernity. A major source of forgetting, I want to argue,

is associated with processes that separate social life from locality

and from human dimensions: superhuman speed, megacities that

are so enormous as to be unmemorable, consumerism disconnected

from the labour process, the short lifespan of urban architecture, the

disappearance of walkable cities.”

Paul Connerton

Bernice Abbott, photography. 1984.

The topic of forgetting is linked to place. Anything of our cultural memory. The complex mythologies of memory and place. There are ways one forgets today, and ways of remembering. When Connerton uses the Palestinians as an example of place memory, he touches on an example which perfectly presents the individual and collective mythologies of memory. One of the reasons the Israeli army continue to destroy olive trees is because trees are the last marker for the mental maps of a people being cleansed from the landscape, from their previous home. The erasure of place coincides with the erasure of ritual movement and the fungible nature of ritual behavior in the West. The citizen of Europe and especially of North America is now conditioned and trained to see replica monuments, of just photographs of places as acceptable substitutes for the real thing. The religious always served a secondary function in most societies, and that was to establish the memory of places by ritual repetitive visits. The contemporary individual ever less often even visits the cemeteries of loved ones and relatives. Such events take on a phantom existence almost. One *thinks* about the visit more often than actually visiting. This is related to an increasingly anxiety producing aspect of urban travel, but even in rural areas the sense of geographic vertigo can be acute. But nothing has exactly replaced the idea of shrines. Nobody engages with surrogate shrines, or ironic shrines, or various manufactured faux shrines as if they mattered, or were real.

Here is a longer quote from Connerton:

“We commonly speak of such ceremonies as rites of passage, and in doing so we are inclined to think of the action in question as a matter of diachronic development, as the temporal passage from one stage of life to another. But it is difficult for us to comprehend this as a temporal passage. We grasp this idea of temporal passage by means of our sense of place. When he came to analyse such rites of passage as a threefold process of separation, transition and incorporation, van Gennep described this tripartite process in terms of place.

It was ‘territorial passage’, he stressed, that provides the proper framework for understanding ritualized passage in the social sphere; again and again we find that the passage from one social position to another is identified with the entrance into a village or a house, or the movement from one room to another, or the crossing of streets and squares; and it is this identification built on territorial passage which explains why the passage from one group to another is so frequently expressed

ritually by passage under a portal.”

Mark Wallinger (John Riddy photography.)

The sense of crossing boundaries is often connected very directly with class, and with state prohibitions. But the stoppage of movement carries, or can carry, as much metaphoric and allegorical meaning as actually crossing it. The sense of place, of space, and its increasing vagueness is a product of today’s architecture. This is the loss of an ability to experience space, in a sense. To read space, and to feel it, to recognize those emotional interior memories that are cued by place. For it is place, it is those spaces with names, or identities. And that becomes a hugely complicated topic.

The pre modern world was one in which ritual pilgrimage was part of a shared social identity, but also part of an imaginary geography of values and beliefs. I feel increasingly that today’s last two generations treat the idea of place-significance only in the most instrumental terms, and by exchange value. There are no olive trees of the mind left in the U.S. today, there are only strip malls and highways and cheap restaurants. And booking a seat on SAS or Continental airlines to get to the pilgrimage site is really failing to understand the point of pilgrimage. Entire social reality, for some people, in the middle ages, was made up from elements of pilgrimage. And this does beg questions about travel and leisure today. The sheer duration of travel in, say, the 19th century — that idea which is familiar by way of Dickens or Tolstoy — is one of conversation at the Inn. This is obvious stuff, that electronic media, technology, has further isolated us. But it has changed the shape of mental maps. People in the West no longer have actual markers in the physical landscape to orient their life, or remind them of values and beliefs. Without such things, the modern urban mega-cities (perhaps even any city over a million) are strange deserts of social starvation.

Noh Sang Kyoon

Today there are sentimental versions of ritual. Characters in Hollywood film and TV will remember back to when ‘dad took me fishing’ or whatever. This seems to occur in almost every single show in fact. This is one of those staple plot moments that has little corresponding legitimacy in real life. Even if dad DID take you fishing, its usually remembered in complex ways and often ambivalently. And yet people will find such kitsch storytelling moving and emotional. They are moved by the earlier memory of pretending. The silent voice in their heads is mouthing the words ‘I remember this kind of fake memory from before and its so touching…’.

The numbing quality of most urban centers today, in North America, but really in the U.S. in particular, has less to do with celebrity architects and their major projects and much more to do with the crappy cheap junk building that one sees everywhere. The accumulative affects of living with such stuff, and with traffic jams and deteriorating streets and bridges and water systems include a battering of aesthetic sensitivity. There is the natural tendency to look away. To forget you saw it. One feels that way with much of media today, too. The desire to forget. Collectively then everything feels fraudulent and manipulative. And I don’t think one can overestimate the degree of manipulation in daily life. This is the byproduct of an age of commodities and marketing. But at some point, a point that may now have been reached, there is an intentional quality of willful blindness in contemporary society. Coupled to the erosion of language.

Kim Jeong-hui. Korea 1786-1856 (Chusa)

James Boyd White wrote a fascinating small book in the 80s, called When Words Lose Their Meaning. White was a lawyer and a law professor. The most interesting chapter in that book was the one on Samuel Johnson and his Rambler essays. Because what White is proposing in his analysis of Johnson is that without an ability to speak clearly, to develop language skills, there will be a resulting lapse into reaction. White argues that Johnson constructs a moral language by making the reader aware of the conditions of his own life. And to the precariousness of assumptions and the uncertainty of everything, especially the *truth* as we know it and experience it. And in Johnson’s definitions are startlingly perceptive insights. He defines ‘resentment’ as a union of sorrow and malignity. The end result of Johnson’s didactic essays is that platitudes do more harm than most any other vice on the human psyche. I mention White because I find I surprisingly often have occasion to remember this book. The chapter on Thucydides is also very good. And I think I return to it because it is both so unfamiliar and out of fashion, and that it reminds one that community is shaped by discussion. And one cannot discuss the world around us without some ability to know the meaning of the words we use. And we cant discuss the world with people who tear up emotionally at earlier memories of fake emotions. “I had that very same fake memory just last week”.

It is the social aspect, and the idea that community is damaged when people converse in platitudes and without the appropriate awareness of their own resentments and angers and anxieties. The contemporary world is almost only platitudinous — it is marketing speech, and the visual grammar of the world is equally distorted and damaged.

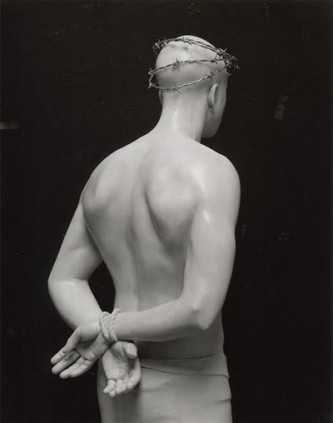

Gutai Group, 1950s.

White mentions how Emily Dickenson created work that later made Wallace Stevens intelligible. She created precedent in a sense. In an interview White is actually asked about pilgrimage in society and in art. That certain works are tantamount to journeys we take, and take again, and again.

“For me reading of the kind I write about is always rereading: These

are texts that have compelled and rewarded my attention, not just

once but again and again, and in new ways when I come back to them

at a later stage in life. I started reading Homer as an adult about

twenty-five years ago, and am still doing so; much the same could be

said about Plato and Austen and Shakespeare. And I read for an

education: That is, I read these works as written by individual people,

each situated a certain way in the world, and speaking to us; and I do

this with the object of learning as much as I can from the activity in

which they offer to engage us.

In doing so I give myself a set of memories that I can use to help

understand and structure my own experience, both in the law and

elsewhere. By this I mean nothing esoteric. All of us, I think, make

our way through life by bringing to bear on the present our memories

of the past. We have heard this sentence, or that, in one version or

another, a thousand times, and know how to read it when it comes

again, whether as a surprise, a joke, or a deeply felt allusion. The

same is true with social relations: We read this gesture or that against

a background of prior gestures, by which it gets its meaning.”

Heesung Chung

The general science or study of social institutions of memory, or just one, the institution of memory, falls under the aegis of both literature and philology. Rather the science of studying literature is philology. Literature is a form of institutional inheritance. Edward Said toward the end of his life expressed regret that philology was dying out. Jerome McGann wrote….“criticism— philology studies

the documentary record on the assumption— in the words of the late D. F. McKenzie— that the documents carry the evidence of “the history of

their own making.”But all texts are evidence of their own making, it’s just that the making of many, or most texts is mundane and even regressive. McGann’s book on digital philology, sort of, is quite wonderful in surprising ways. He says at the end of the introduction, apropos of Forester…“Forgotten gods lurk in those small things of the world and they have long memories. Philology tells us we should listen to their hundreds of voices as we try making our ways to India.” The loss of memory, collectively, damages everyone, even those who work hard at remembering. The loss of memory in others still wounds me, and you. This is also relevant in a sense for those aspirational Asperbergers fakes from last posting. Poetics is removed, and you have emotionally dead art, and you have spread sheets and data. And then one can’t even remember the spread sheet. For, why bother. Except that if the world is made up others who have lost the thread of their private spread sheets, we are living in Purgatory. The passionless ‘realistic’ personality has infected contemporary culture and it masks aggression. The realistic man, though increasingly women aspiring to be man like, is the patriarch. The upholder of repression. And that American Calvinist or Puritan grimace, the squint of disapproval is being replaced in post modern life by the blank stare, the affectless dullness of people who laugh two beats late at every joke. Today, even manic behavior feels too slow. The manic phase of the bi polar sufferer today is ratcheted down even. As the world allegedly and famously speeds up, the quality of all else has slowed. And memory is growing ever cloudier.

Vivienne Shark LeWitt

“…the history of philosophy . . . a history of mistakes, awkwardnesses, distortions, and sinister failings that had to be.”

Bernard Stiegler

This is from McGann’s book, too. And it links back to Black Mountain College, to an idea of accepting that mistakes are not mistakes if they occur in good faith. Or not really good faith, but with clarity. Ornette Coleman once asked “can you intentionally play a mistake”? It is about the respect one gives to one’s practice of attention. This is aspect of learning to garden or build fences that is important. Gary Snyder once said, ‘learn to do one thing really well….THEN go and learn to be a poet’. If there is clarity, and respect, then the outcome is less important. The artist, the philosopher, the monk — mistakes are not mistakes. That is the message of Pasolini’s Gospel According to St Matthew I also thought. Jesus as a labor organizer, erotically indeterminate, but therefore beautiful. Erotic beauty is always partially unformed. Completion is not as beautiful as incompletion. In people or in artworks. It is not about being right. That is so important I think. The revolutionary who insists on being right is a counter revolutionary and a cop. The demand for being mistake free is sexual disfigurement, and a kind of sadism. The sadism of the mistake free is the kind that is not deterred by awakening to the fact he or she is beating a masochist. The fascist is never beautiful. They can be almost beautiful, or briefly beautiful, but it is that changing of the angle of the head, in an instant, that reveals the snake, the birth defect, the sense of deadness. And this brings up a final sort of coda observation.

Ray Johnson, at Black Mountain. Hazel Larsen Archer, photography.

My response is largely to this quote (and on place/memory):

“Rice believed that students must find common ways of doing things. Manual labor was a part of the curriculum at Black Mountain. If today, one can almost immediately hear the snickers and jokes that would follow the introduction of that idea, it is because students have so completely abandoned any thought of institutional learning that does not further career, and involve testing.”

Of course, there are many people that are both students AND labourers. Many university/college students must work while they are getting their education because cost of school is so high. That being said, this type of labour is framed toward—as you say, John—paying for the education, which will further the career; it is goal oriented. There is, I think, a difference between going to school while working at McDonalds on the side, and going to school while actually caring for the school on a material level (building it, maintaining it).

I have just started studying as a ph.d student this fall, but I also am a custodian at my university (I was a custodian before becoming a student). Although I only clean one day a week now, and could get by financially without doing it, the custodial work is—I feel—fundamental to my education. My custodian colleagues are dear friends to me, and so are the very buildings that I take care of.

Politically, our social position as custodians, in regards to the university institution, is extremely fraught. What I learn and how I learn is coloured by my own relationship with the institution’s care (or lack of care) for its working class employees. Right now we have a union and a contract, but the university is constantly threatening to contract out its custodial staff, meaning that custodians will no longer be officially affiliated with the school. This is a deeply problematic ethical situation indicative of the business model that universities operate under. If our university contracts out its cleaning and trades staff, they will—We will—be endorsing an economic regime that creates unstable job positions, positions with no benefits, and positions at minimum wage (what a contractor would pay). As a student, teaching assistant, AND custodian, I feel a part of a much larger, more important struggle; I am more aware of living and impacting social-political situations. And maybe I’m not typical, but I am NOT doing my degree to get a job, and I have never thought of education that way. I feel that what I am doing right now is important and challenging. And maybe soon students will stop caring about the career thing and demand a different sort of education. Getting a career is so Boring—and increasingly impossible…

I feel that my current labour process (both cleaning, and studying), has helped me avoid the terrifying gap between work and life. My life and work are one. And though my positions in the university institution are fraught with challenges and struggle, I am not entirely alienated from my body or my position in physical space. It feels mysterious and yet, grounding somehow. I am living architecture.

And in regards to space/place/memory/”Looking away”…

Something else I have enjoyed from being a custodian at my university, is indulging in an imaginative, embodied appreciation for the university as a material, architectural entity. There is a certain respect I have for the spaces that shelter me and my comrades. The spaces are heavy with history. They tell stories. Walking down a deserted hallway at 6am, and the walls hum with the footfalls of thousands of students, sweating, crying, laughing, talking—the walls and floors record it all. Every crack in the tiles, every scribble on the bathroom stall, every muddy footprint in the corridor—these have a whole history of beings behind them. If I just engage with these traces for a moment, that history opens up to me, and the possibility of that ‘opening’ is far more moving than my narrow vision toward some career goal that might cause me to fail to notice, and thereby never fall in love with, the vulnerability of a nosebleed on the bathroom counter…

@calla:

yeah, its that word *work* that is confusing. Working for minimum wage is alienated and soul killing. Yet collective work on a collective project is quite the opposite. And really, of course, as you describe, often salaried work can also be satisfying. I know carpenters love their jobs. There is craft. But i once had a nightwatchman job at a medical center in LA. Small medical center. Nobody was there but three or four beds on the second floor. And a night nurse. Otherwise just me. I made the rounds. Seven floors of complete emptiness and silence. I LOVED THAT JOB. I loved it. I read most of the time and once an hour took rounds and checked on things. I had keys to everything…except the pharmacy……and so i also could explore where i wanted. The doctors room in the penthouse always had left over food from conferences. Great catered food. So I had dinner there as well. But all of us who had that job loved it,. And we all became friends and covered for each other. There was only four i think. On rotating shifts but i always chose graveyard. There is something so surreal about urban life between 1 am and 6 am. Ive always loved that. Lynee Saville has great photos of that. Druv Malhortra does it in Mumbai. Late night wandering and both capture that magical strange quality. And yes, i understand that sense of respect for shelter. And yes….student debt is another huge topic. Working to get through school.