Gerhard Richter

“If there is no activity of interpretation, I cannot understand

how any living organism belonging to the human species could

survive.”

Andre Green

Squiggle Lecture #3

“The question of experience can be approached nowadays only with an acknowledgement that it is no longer accessible to us.”

Giorgio Agamben

“The human face is a void force, a field of death.”

Antonin Artaud

“…the key question is: Who do elected representatives represent? The answer is not the electorate, but the class that has the resources to invest in the political system—resources politicians need to get elected. This is none other than the class of capitalists.

Still, despite the glaring disparity between the promise of procedural democracy and its outcomes, most everyone celebrates it, or talks about democracy as if it had only recently been negated, as if the domination of capitalist society by capitalists is a recent phenomenon and not a necessity by definition.”

Stephen Gowans

I find today, in the West anyway, that the most effective mechanisms of control are those of limited and managed token opposition. The society of control provides almost countless examples of figures and ideas of token resistance. I will return to this idea below, because one sees it so clearly in the current U.S. election period, and also in the propaganda at work to discredit Corbyn in the U.K. There is also a regular employment by the state of the *limited hang out* strategy. More on that below…but there are linkages in the how manipulated the populace is today, and how this same public cannot identify their own best interests.

Agamben’s thoughts on the loss of experience echo Benjamin (who he quotes in his essay) and they are directly consequential in political terms as well as being the defining characteristic of contemporary culture and art. That daily existence of most in Western socities, at least North America and then the larger cities of Europe, is intolerable. And it has an effect on art and culture, but first, it is a byproduct of how control and authority are exercised. And looking at authority in terms of narrative, and how a political spectacle is used to keep the populace (or enough of them for the purposes of control) at a very specific distance from personal interaction with laws and regulations, in place of which only the effects are experienced. The appeal to authority in media is built in. But that quality pales before the narrative authority of the system itself. How can one explain the fact that people so docilely adhere to voting for one or another candidate with whom they really share very little in terms of values. Most Americans for example distrust government. Most Americans also vote for someone who is a part of that distrusted government.

Louise Herman

Agamben says all authority today is based on what cannot be experienced. The slogan, says Agamben, has replaced the proverb and the maxim. This is a lot like what I’ve written regards the loss of allegory and myth, even metaphor. Watching tourists take selfies in front of, say, the Eiffel Tower, or the Cathedral of Sevilla, speaks to a desire to cede authority to the cataloguing of affect. The experience of the Cathedral space is rendered irrelevant. The political candidate today rarely says anything that is related to human experience. Benjamin’s fondness for the German Romantics came out of his recognition that external reality, or nature, was increasingly seen as ‘there’ for human manipulation and control. The Romantics thought emphasized an intuitive (mystical) illumination, and not on the instrumental critical analysis of experience, in an effort at conquest. The latter which denied the importance of a certain interior human judgement. Benjamin was emphatic, however, that the early Romantics were not part of the later emotionalism and sentimentalism associated with the movement. Benjamin’s first doctoral paper saw these early Romantic writings as the basis of much later modern critical thought. Benjamin believed that artworks were always subject to interpretation only in conjunction with historical factors and not with the intention of the artist or with the overt message of the work.

For the medieval mind, science was quite separate from experience. But that had to do with the religious quality that shadowed experience; and the desire to prepare one for death (or a life after death). Science was measuring things. Agamben saw the ascension of science as a process of changing the very idea of experience. Or rather, to create a single new locus for both, that of ‘consciousness’ (cogito). Consciousness was then to be treated scientifically.

Callum Innes

Benjamin’s study on Trauerspeil (German mourning plays) has something in common with Artaud’s writing on theatre. “In this state of disruption the present age reflects certain aspects of the spiritual constitution of the baroque, even down to the details of its artistic practice.” Walter Benjamin.

Graeme Gilloch’s very good book on Benjamin is useful for understanding his work on German tragic drama. He writes; “Benjamin argues against the conventional privileging of the symbol by demonstrating how, far from being an inferior poetic device, allegory accords with, and gives expression to, the ‘ruinous’ world and ‘creaturely’ human condition envisaged by the baroque dramatist.” At it’s most simple, allegory is a figure of speech in which something, an object, stands in for something else, or more, that isn’t present. However, allegory is rarely simple. And often, its multiple significations can become their opposite, or both opposite and identical. For Benjamin, the symbol (a more tidy designation) is subsumed, in a sense, by allegory. The symbol, as Gilloch points out, does not disperse across a plethora of referents. The symbol then, is self contained. It provides, even if only momentarily, a picture of totality. In allegory, believed Benjamin, comes a fullness, however untidy, that represents the entirety of the world’s fragmentation. Hence allegory contains an implicit critical quality. But it does something more, it introduces the inescapable aspect of historical time. Allegory, in terms of narration, is much closer to dreams.

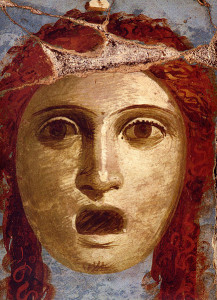

Antoine Coypel

“..in allegory the observer is confronted with the *facies hippocritica* of history as a petrified, primordial landscape.”

Benjamin

Benjamin believed that the *ruin* exemplified the allegorical vision of the world. Today’s fascination with ‘ruin porn’ suggests the outlet for lost allegorical reading of narrative and image. But it is presented in a carefully limited hang-out sort of way. How successful such control ends up is an open question, however. And here the idea of experience and domination becomes very complex. For Benjamin the corpse was the ultimate representation of the history of the body. As Gilloch says, the allegorical mutilation of the body is not meant for salvation, but in order to disclose the hopelessness of the human condition. The endgame for natural history.

Samuel Weber notes that Benjamin gave great importance to the idea of the theatrical. “The ubiquity of the theatrical, if not of theatre, is thus the result of the absence of clear-cut authority, structure, or meaning.” He mentions Benjamin’s interpretation of Kafka’s Natural Theatre of Oklahoma in Amerika, in which the criteria for acceptance is indecipherable. As Benjamin says; “nothing is demanded of the applicants other than to play themselves.”Kafka never finished this novel, and in fact the Natural Theatre of Oklahoma is introduced in the last chapter he was ever to write of that novel. As Weber points out, the incompleteness is perhaps the novel’s most revealing trait. I have written before about how ubiquitous is the idea of ‘interruption’ in contemporary life. And here there arise all those themes of 20th century imagination; voyage, exile, migration, and the stranger. All of them, of course, have always been themes of the human, but today they are increasingly illegible because of the loss of experience. And the narratives of mass culture reveal the poverty of the imagination of those who produce this stuff. But it’s not just the corporate product that lacks imagination. Shane Carruth’s second film Upstream Color, made entirely outside the Hollywood financing machine, is an example of the poverty of the imagination at large. It is exactly random isolated bits of pseudo cleverness masquerading as alternative or experimental, or something. In fact the most striking quality of this film is its narcissism. It is not in any way a counter vision to mass culture. To the status quo. It occupies a niche market OF the status quo.

The Celestial Worthy Taiyi (detail), Southern Song dynasty, 13th century.

But in a sense, it feels like the ideal film for a year in which the transparently deceptive Bernie Sanders campaign is being embraced by white America. The ‘new alternative’ is a nakedly venal and unpleasant man, one with a long history of opportunistic voting in congress but with a preternatural ability to push the right buttons for his targeted audience. Shane Carruth meets Bernie Sanders meets Marina Abramovic. This is the new *nothing* culture. It is also a culture of white privilege, it should be noted. Sanders is, besides his odious position excusing Israeli aggression, and the fact he enthusiastically supported the NATO aggression on the former Yugoslavia, a sort a non-threatening avuncular old Uncle from the very white state of Vermont. What is relevant here is that Sanders is the managed symbol of opposition. As I speak about later, the loss of self in contemporary society has taken the form of a kind of self objectification (on one level). An over-identification with commodities. The political arena is then simply more commodity shopping and Sanders signifies the most anodyne form of nominal opposition. He drains energy form those pockets of genuine grass roots organizing, and positions himself as a white man of a certain age from a state signified as an almost Norman Rockwellian symbol of cleanliness, with an added small town nostalgia. The details become irrelevant. His actual voting record irrelevant.

“Nostalgia, often found under imperialism, where people mourn the passing of what they themselves have transformed.”

Renato Rosaldo

Sanders is nostalgia.

For the white population, Sanders is a trusted white brand in a sense. There is also the tacit understanding that ‘he won’t win’. Which I suspect comes as a comfort to many, but his running (not as an independent) is a controlled bit of faux resistance, and one in which the white voter can still feel white people are the ones making decisions. He de-facto authenticates the Democratic Party. The electoral shopper then has identified him or herself with progressive values, a nostalgic small town quaintness (much as many of the white affluent class shop for rustic natural fiber clothes or old farm implements to use as decor) and all without having to allow into the purchase any question of race or Imperial domination.

The control mechanisms in play help arrange a world view in which deceit, greed, selfishness, racism, and tolerance for authoritarian values are validated. And cutting across all this new cultivated and manicured *reality* is a sense that ‘perception’ (merely perception) is perfectly normal, even natural, and that perception is reinforced by the quality of acting the role of oneself. This is also a Kafka-eque trope, for ‘acting’ (as Weber observes) is to be distinguished from action, or an act. Benjamin saw the distinction as one of a dependence upon a script. Waiting for your cue — is part of the wide canvas of obedience and alertness to command. As Benjamin said of actors…“for them hammering is real hammering and simultaneously also nothing.” And this phenomenon extends to the idea of framing. There are paradoxes in this, but for the non-allegorical artwork the frame is crucial. It makes the actual place (and history) nearly irrelevant, and the artwork can float in a vacuum in which the audience may reflect on something cut off from the human and history. The theatre that looks to duplicate reality is the regressive theatre. Even where the intention to duplicate is highly artificial. Only in a staging in which the reality IS the stage, can allegory take place and where the ideas of both social history and individual awareness be exercised somehow. This is also something relevant in terms of art that tears away the deceptions of the cogito. All great theatre is, then, at least partly a theatre of pre-history.

Mask of woman actor, Pompeii, Casa del Bracciale d’Oro

The Natural Theatre of Oklahoma is described to Karl in an early chapter as limitless. Karl asks Fanny, if she has seen it and she says, well, no, but I have colleagues who have. For Kafka, the theatre here is then far more than a stage. It prefigures the business of perception and acting. This inevitably brings in a discussion of mimesis. For acting is involved in both mimesis, and in gesture and finally with text. Agamben (and others, such as Delleuze) seem to approach film without having an understanding of what Benjamin (and Adorno of course) saw as the importance of mimesis, but also is oddly undialectical. This is true of Ranciere, too, and consequently their writing on film is oddly flat. I don’t actually believe they go see film very much (which might have been good, in theory, but is proving not to be). This is also, it seems to me, a place where one almost intuits the differences between theatre and film or TV. Perhaps the sheer volume of film and screen image has allowed a re-introduction to the immediacy of the body in theatre. And to gesture, and to the ways in which narratives on stage bypass the conscious mind far more easily, and unleash the uninterrupted stream of the allegorical. In film, there is a natural montage quality, and the editing combine altogether to open another aspect of dream life, but I’m no longer sure that film is particularly prone to allegory. The allegorical is eaten up in the optical instruments and today, more, in digital technology. Even the very best film now is really only great because of the narrative, but that quality may in fact be enhanced, paradoxically, by the shrinkage of allegory. But for now, to return to the stage.

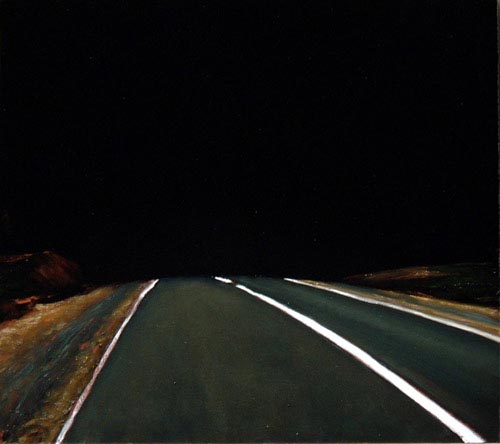

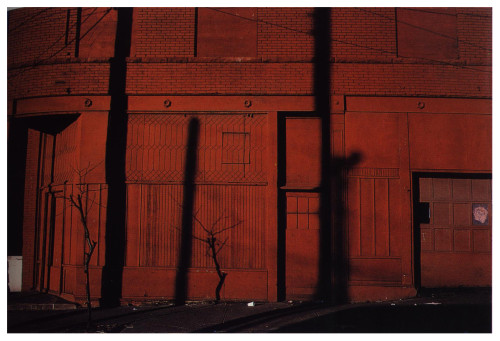

Richard Mirsach, photography.

The evolution of acting since the advent of film and TV has not really been examined to the degree that it should. I think partly this is because in the West, acting has become the performance of celebrity. And partly, also, because nobody quite knows what to do with film acting, theoretically speaking. And thirdly, today most everyone is acting all the time, in their own private home movies. That is probably an entire several books unto itself. For the purposes here, the question is more to do with the exchange of inner life, and a reality formed in conjunction with individual history as well as social forces, and a reality of screen life created and sustained and repeated in a constant loop by corporate mass media. The dream life of the film today is too often a captured dream, one that does not allow for mimetic or physiogmnomic knowledge. Benjamin believed, possibly anyway, that film would return image to its place in nature, a place that been disrupted. This is, of course, seventy five years ago — and today’s electronic media has far more heavily conditioned ideas of space and time. I wrote last time about anticipation and expectation, and I think modern screen hegemony has normalized artificial expectations and a kind of cued anticipation. The role of cues, both visual and aural and ideological (as it were) have become more pronounced over the last twenty years. Today’s audience, in fact today’s citizen, is dependent on his skill at reading, or deciphering cues. This is mostly the result of a culture heavily influenced by the marketing industry.

It was Hans Sedlmayer who wrote that lifeless things, inanimate objects, without expression will acquire a face and eventually gaze back at the viewer. So here is the conjunction of several threads of thought: the theatricality of psychic life, and Kafka’s great world stage in Amerika, mimesis as Benjamin and Adorno understood it, and the erosion of experience for the contemporary public who exist in a coercive Capitalist state and this in turn is a part of a larger topic having to do with technology in general. And all of this contributes to the essential interrupted quality of modern life.

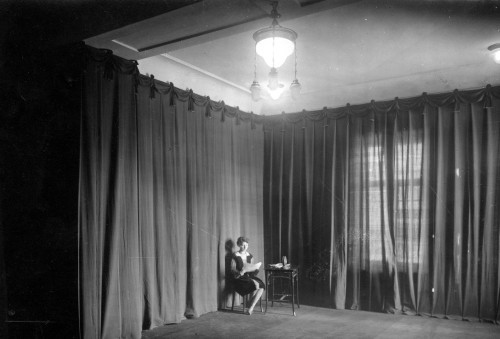

Jan Bulhak, photography. 1928

To return to Kafka’s theatre; in a book which I think is certainly Kafka’s greatest, and in the Great Theatre of Oklahoma can be found the most perfect metaphor/allegory for later Capitalism that is possible. But more, it is an expression of the impossible quality of our psychic journey toward completion. For the character of Karl Rossman, there is no certainty that the theatre even exists. There is, as a side bar note, something in Amerika that resonates with another fantasy America, that of Charles Dickens in in the sort of underrated Martin Chuzzlewit. This is as melancholy a satire as one can find this side of Swift, and Dickens distaste for slavery and the average American was clear.

“An American gentleman . . . likewise stuck his hands deep into his pockets, and walked the deck with his nostrils dilated, as already inhaling the air of Freedom which carries death to all tyrants, and can never (under any circumstances worth mentioning) be breathed by slaves.”

Joyce McDougall (photo by Bracha Etinger)

Gerhard Richter wrote, in a short essay on Adorno; “…fidelity to established rules and procedures is seen as anachronistic; and even as the last remnants of human relations are struck with sameness and commodification, too much fidelity to one’s 500 closest friends on one’s favorite social network website only becomes a liability. In order to exhibit the brand of so-called flexibility demanded by the neobliberal market, one must be prepared to press the delete button at a moment’s notice. But the love of fidelity, and the dialectical fidelity that Adorno’s model of love imagines, is one in which fidelity itself, if and when it loves love as love rather than as an internalized form of exchange value, is a love of resistance, and it loves the resistance that *is* love.” As Richter points out later, paraphrasing Kierkegaard, loving one’s neighbor is hard when the world is without neighbors. The loss of empathy and cooperation is further killed off in the diabolic logic that is the driving force of Capitalism. For the artist who looks to find expression outside the dominated world, the resulting counter-force is one driven by a kind of paranoid suspicion of any audience’s response. Richter cites Adorno’s late remarks on music…

“Music which lets itself be driven by pure, unadulterated expression becomes highly allergic to everything representing a potential encroachment on this purity…”

Kaye Donachie

Richter saw this issue of fidelity, per Adorno, and the latter’s notion of love, which are intimately connected, as the place of optimism in an administered world. Faithfulness is a kind of love, faithfulness to anything. And a kind of resistance. The atmosphere in the U.S. today is one of infidelity, of nervous anticipation for the next call to opportunity. Nobody knows what opportunity looks like. But they believe they will know it when it arrives.

The principle of the dominated world, of advanced capital, is one in which inner life becomes an owned private existence, a shift in subjective imagery. Adorno saw the pre-formed subjective experience additionally betrayed — in the sense that, for example, anticipation is rarely rewarded. In fact, even when the knock at the door, the knock of opportunity comes, the opportunity turns out to ephemeral. The promise is broken. Even chance random conversations today are so barren and anxiety ridden that something of a complicity with state controls is expressed. The loss of allegorical dimension means one is always trafficking and conversing in ideas and in a language that has been denuded and hence, as its shell remains, it is injurious and full of only sharp edges. For the instrumental language favors the simple metaphor, the simple simile, the war symbol. Adorno described affability as the discourse of a totally administered world.

Michael Kenna, photography.

In contemporary TV, the anxiety of the entire culture becomes encapsulated in the exaggerated narcissism and self interest of many of the characters. I can think of two different shows in which teenage children discovered their parent(s) were secret spies or revolutionaries of a sort, or had some other secret — not immoral secrets, but just secrets. Other lives…in each case these other lives were, as I say, rather noble. In both shows the children are hysterical with self righteous anger. In another it is a wife. In fact two shows feature wives furious at husbands for secrets – not again, infidelity or illegal activity, just complicated secret activities. And again the response was a tearful sense of martyrdom. ‘How could you not tell me’? etc. Now, had I discovered my parents were spies or secret agents or had secrets of any kind I would have been thrilled. If my wife turned out to be a secret revolutionary, I think I might find that pretty sexy. But the white consciousness of the west today is one that can only know an ersatz victimhood. And the expression of emotion is allowed only in maudlin sentimental self pitying grief. White people problems abound. It is hard to think of a show in which some character is not affronted and indignant. And always with tears in their eyes. It is a substitute emotional release, probably standing in for a sub-conscious understanding of the massive crimes of the society at large. It is also a form of weird co-dependent neurosis. In a certain sense the idea of co-dependency is deeply flawed, and an expression of an ego psychology of adjustment. But in another sense, on a collective level, it seems an actual maladjustment, and one perfectly in sync with a society of snitching and shaming. But there is a second theme here, in the loss of experience and the representation of the shallow emotional — and that is the dialectic of participation. And this is again something Adorno was quite articulate about, especially in Minima Moralia.

“The detached observer is as much entangled as the active participant; the only advantage of the former is insight into his entanglement, and the infinitesimal freedom that lies in knowledge as such.”

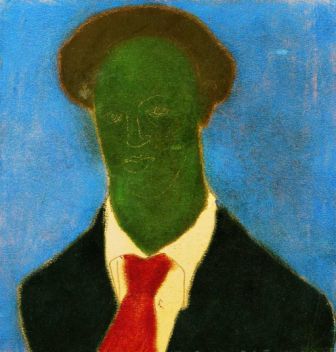

Lajos Vadja

Contemporary life is largely shaped by economic inequality. Everything else follows along in the train of that. That said, those secondary consequences hold great importance as the seeds of later resistance. For the left today, the class of academic and faux left and self promoting left, the disfigurement of the psyche is huge. The self examination (even when the critiques of social issues are good) is lacking. And there continues the anti-intellectualism lodged in much of the older white left. That factory Marxist mentality. The flip side of which is the Bhaskar Sunkara entrepreneur style-left. The used car salesman left. And running across all this is the branded liberal press celeb writers; the Laurie Penny or Molly Crabapple, or Danny Gold, or China Mieville kickstarter left. People who even when they are right, are wrong. But I digress…sort of. Christopher Bollas coined the term ‘Normotic’.

Bollas sees this individual fleeing from dream life, from imagination, and from, in fact, all risk. This is an echo of Randy Martin’s notion of a financialized model for psychological behavior. Risk management. Bollas says the psychotic has gone off the deep end, the normatic has gone off the shallow end. And really this is what I am trying to get from an aesthetic point of view. The new post experience administered psyche is flat lining emotionally, but more than that, it is a kind of self-reifying subject. Bollas sees this person as experiencing themselves as commodities. As Sherry Weber Nicholson quotes Joyce McDougall, who speaks of the ‘death of curiosity’. Nicholson writes…

“The patient talks of people, and of things, but rarely of relationships between people or things. Nor does there seem to be that intermingling of conscious and less conscious layers of meaning in the patient’s communication.”

The eroding of experience means really a loss of history. Both social and personal. McDougall says the patient displays “a banality of thought akin to mental retardation.” This is the new mass public, the new mass man. I suspect many people imitate a crude version of what they see in TV and film. Everyone is waiting, anticipating the Great Theatre of Oklahoma is about to start hiring. The society of the West today is so awash in entertainment violence, and so buffeted with constant news-speak, platitudes and disinformation, that as children this process of deadening begins as a protective measure. This may not be quite right, though, because there is also a sense that somewhere in the repressed material of these subjects their lurks the phantom recognition of the collective death wish embedded in Capitalism.

Louise Lawler

I have suggested before, as have others (Rob Weatherill for one and Sherry Weber Nicholson too, in her analysis of Adorno) that there has been a traumatic interruption at the pre-Oedipal phase of development. I am reminded here, too, of the work of Wilhelm Reich. But as Nicholson astutely points out, behind all of this lurks the militarism of the Imperialist state. The addiction to mass industrial level violence as the meta solution to everything. It is as if violence on this anonymous scale becomes a phantom object that never abandons you. Both Adorno and Marcuse saw the media depictions of war as having a numbing effect and a normalizing of mass death. And I think today it has come to have linkage to desire. It is also a normalizing of obedience, or more precisely, a valorizing of rote obedience as a kind of mental health. The model for a healthy normal is now the person with total amnesia and loss of affect, an android servant to power. Adjustment means adjusting to a society in which one must think of oneself first. It is not very far away from Ayn Rand; only the selfishness is not really about self, for there is no self.

Bollas writes of a lack of unconscious freedom. And that without this, creativity is stifled. The loss of experience is obviously connected to this idea of *self*. A highly complex discussion, far exceeding a simple blog post. But I do want to suggest a few things, tentatively, in relation to the loss of unconscious freedom. Firstly, the idea of internal objects posits a huge matrix, and one that is fluid. It is something beyond representation. Lacan would put into the category of the real. It is beyond our imaginary or symbolic definitions. If you meet someone for a single minute. Exchange a few sentences in conversation and then part, you will still have a better sense of this person than if you read an entire 500 page dossier on his or her life. Here it is useful to keep in mind Wittgenstein’s ideas on meaning. Bollas writes: “I think that one of the reasons *self* is an apparently indefinable yet seemingly essential word is that it names its thing, saturated with it, the indescribable is signified.” I am reminded of DeNiro talking to his mirror reflection in Taxi Driver…”you talkin’ to me?” The problem is that however complex our sense of what we mean by *I*, it is one that is grows more dense as we age. It is composed of memories, and our individual histories, especially histories of desire. Bollas says we have a ‘sense’ of ourselves. A presence. It is my suspicion that as the normatic psyches develops especially in situations in which parents are either absent a good deal, or mirror the child in a way that deflects the infant’s gaze. Objects intrude where tactile experience is expected, and the face of the mother is missing. And remember, too, that the society is now one in which corporations are granted personhood. In a culture with extreme amounts of screen time afforded many children, the more affluent, there is likely a kind of (sort of riffing off another Bollas idea) extractive introjection — not from the psyche of another, but from the personalities of the screen. As interior lives develop with an acute dependence on ‘things’, commodities, the electronic media becomes an uber-thing, a place where the extraction of value and opinion is particularly easy, even invited, solicited, and hence the new robot person comes to believe they are the creator of these values — and by extension in a sense the creator of the screen tape they play in their own head.

Harry Callahan, photography. Kansas City, 1981.

There is a resulting kind of dementia that occurs, now, but is controlled.

Joyce McDougall wrote, in the context of patients exhibiting a mechanical thinking (this from 1975)…“‘What kind of woman is your mother?’…’Well, she’s tall and blonde.’…’Were you upset when you ran over this woman with the baby?’ ‘Oh, I was insured against third party accident.’…These have a psychotic resonance, yet there is no resemblance to a psychotic ego functioning in other aspects of these patients’lives…De M’Uzan has pointed out that the outstanding feature of such thinking is its detachment ‘from any

truly alive internal object representations’.”

The Société Psychanalytique de Paris (SPP), under the direction, I believe, in the 70s, of Pierre Marty, were discovering at the time a marked increase in this mechanical thinking, a loss of the ability to fantasize and imagine difference. McDougall also noted that such patients, when faced with the loss of someone close, were incapable of mourning. All of these symptoms were easily disguised, and managed, often, by the patient. They fitted seamlessly into daily life in the Spectacle. Consumer culture was both cause and effect. The insane seemed to function quite well in the system.

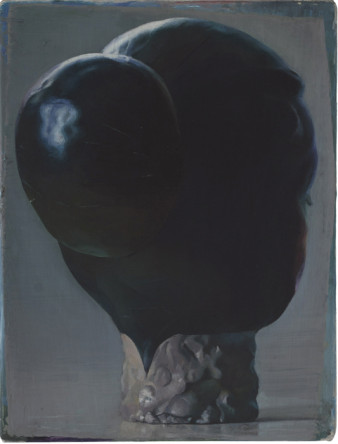

Damien Meade

“If psychosomatic personalities may be said to be ‘antineurotics’ due to their inability to create neurotic

defences…they may also be considered as ‘antipsychotics’, in that they are ‘over-adapted’ to reality…The

desperate search for facts and things in the external world and the tendency to treat people as things in an

attempt ‘to grasp at some fragment of experiencing’.”

Joyce McDougall

Joseph Dodds has an excellent paper that serves as an overview and history of the SPP. And I am borrowing here from that. Now, the larger political implications can be traced back to Benjamin’s dispirited sense of much Marxist writing on culture in the 20s. In 1930 he was given the position of editor of a new art and culture magazine Krise und Kritik. He resinged within a few months, despairing at the quality of the work submitted, but more, at the disinterest of the left in culture and art. In a letter to his friend Max Rychner, he described the propagandistic materialism of both the bourgeois side, and the Communist side. His disappointment led to the writing of his essay Author as Producer.

“…the tendency of a work of literature can be politicaly correct only if it is also correct in the literary sense.”

Benjamin

As Gilloch sums it up: poor works of art make poor politics. And this is irrespective of the intention of commitment of the artist. This is, of course, not a blanket truth. And there are always anomalies in which reactionary artists create meaningful work, for example. However that is debated, the validation of bad art, even if in agreement with one’s politics, is hugely reactionary in the end. But this reality will bring us back once again to the psychic traumas of life under Capitalism. The administered world affects everyone. Benjamin pointed out, what I think I have tried to do in various ways on this blog, and that is that “the context of living social relations”is crucial to the engagement and interpretation of the artwork — and hence the dialectical reading of work often yields surprises. Literary forms, as well as trends in painting, even architecture, reflect, dialectically, the spirit of the age. And all artwork exists in a matrix of overdetermination. Art is a dream in many ways, but in a world that is dissolving dream life, it is harder and harder to find work that is not numbing or simply a regurgitation of the fascist sensibility. Couple that to the fact that behind the majority of popular cultural product are the hands of the state, the proprietor class, and even, increasingly, state agencies, it requires no small effort to tweeze out the autonomous (as it were) grass roots artistic object. The era of the ‘normotic’ robot people.

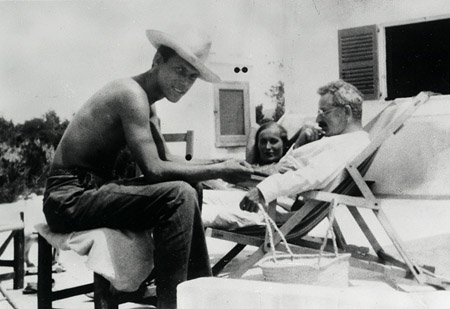

Walter Benjamin, in Ibiza, 1932.

I will end with an excerpt from an interview with Christopher Bollas (and a brief part of a poem from Enzenberger).

“For me, the last epoch of thought that was saying something about

individual life was existential thinking, in the mid-1950s. From that point on, there

is a lot of what I would call “ornamental thinking”. I respect Derrida and Badiou,

but it strikes me as decorative thought, thinking that is brilliant for its own sake

but also without soul, movement, without real, deep conviction. So very few of

these writers can I read, because it seems like literary gamesmanship. I think it’s

the end of signification. It’s hard to read, not really making sense. This means that

the traditional Western mind based on the search for meaning is no longer possible.

We live in market economies, it is as if the economic realm has sucked us in.

Our brains have become part of market transactions. I don’t know whether we will

return to thinking. People seem to be different, my patients, my colleagues, I seem

different. I don’t think that there is the same belief that the search for meaning will

yield arrivals of thought — it seems that the quest has disappeared.”

Christopher Bollas

“The blue sky is blue.

That says everything

about the blue sky.

These flying rebuses however—

although the answer changes all the time,

anyone can decipher them.”

Hans Magnus Enzenberger

(Tr.by Ester Kinsky & Martin Chalmers)

first rate